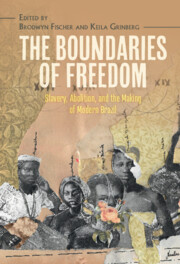

The oil painting Redenção de Cã (The Redemption of Ham, 1895) figures prominently in the life work of the prolific Spanish-born, Brazilian-naturalized artist Modesto Brocos y Gómez (1852–1936).Footnote 1 Originally exhibited with the title Redempção de Cham,Footnote 2 the handsomely sized (199 × 166 cm), signed and dated oil-on-canvas won the grand prize at the 1895 Brazilian national salon held at the National School of Fine Arts (Escola Nacional de Belas Artes, ENBA), where Brocos held various teaching posts between 1891 and 1934. An instant success, Redenção was acquired by the Brazilian government at the urging of influential voices in the Brazilian intelligentsia.Footnote 3 For the past seventy-five years, the work has been part of the permanent circuit of the Brazilian national art museum.Footnote 4 In various retrospective exhibits, in textbooks, and online, Redenção commands outsize influence in Brazil’s visual vocabulary, at home and abroad.

A landmark in Brazilian visual culture, the painting has nonetheless been dismissed for its troubling allegory of race mixture. The notoriety of Brocos’ treatment of an enigmatic Old Testament tale commonly known as the “Curse of Ham” (Port.: Maldição de Cã) conventionally turns on the troubled history of racial thought in the immediate aftermath of slave emancipation. In a 2011 popular history piece about the canvas, Brazilian anthropologist Giralda Seyferth succinctly captures the dominant interpretative framework: “O futuro era branco” (The future was white).Footnote 5 In scholarly literature and in the popular imaginary, Redenção da Cã (see Figure 13.1) serves as the touchstone illustration of the intersection of the ascendant racial “sciences” of the latter half of the nineteenth century and an ideology of whitening and Black erasure that informed early twentieth-century Brazilian thought and social policy. In recent scholarly publications, such as Tatiana Lotierzo’s Contornos do invisível (2017), and in the global imaginary, the canvas stands as emblematic of race and racism in Latin America, notably during the heyday of eugenics.Footnote 6

The burdens of Brazil’s racist past (and present) have often confined readings of Redenção to its allegory of a Blackness disappearing into whiteness. Nonetheless, the painting has been the object of some important reappraisals. Historian Heloisa Selma Fernandes Capel has put the painting in dialogue with Brocos’ theoretical tracts, A questão do ensino de Bellas Artes (1915) and Retórica dos pintores (1933), to understand how the piece works in dialogue with the artist’s evolving sense of fine art.Footnote 7 Art historians Heloisa Lima and Roberto Conduru have discussed the painting in relation to other works about Blacks produced within the ambit of the ENBA and its predecessor, the Academia Imperial de Belas Artes (Imperial Academy of Fine Arts).Footnote 8 Brazilian historians Ricardo Ventura Santos and Marcos Chor Maio grappled with a geneticist’s use of the image to “prove” the racial heterogeneity of the Brazilian genotype.Footnote 9 In 2013, anthropologists Tatiana Lotierzo and Lilia Schwarcz delved into the gendered visual economy of the canvas, setting Redenção within a nineteenth-century white male gaze.Footnote 10 The ugly history of anti-Black thought continues to weigh heavily in these alternate analyses, but fresh eyes have chartered approaches to Brocos’ most well-known work that may not settle solely on the author’s “scientific” appraisal of Brazil’s white future.

Paradoxically, Redenção remains thinly contextualized in the historical setting of slave emancipation, a process completed a few years prior to Brocos’ first rehearsals of the themes later assembled in the notorious allegory. Capel has casually observed that Brocos registered a disdain for enslavement, but how and what Brocos knew of slavery and emancipation have remained largely unexplored in the scholarship. This chapter looks anew at Redenção, its author, and their multiple audiences in the temporalities of slavery’s final decades in Brazil. Its goal is to resituate the notorious canvas within the complex transitions from bondage to freedom that began in the 1870s and lingered through the 1910s. Arguing that Redenção is a painting just as much about a nineteenth-century Black emancipationist past as it is about a twentieth-century post-emancipation whitened future, I will first briefly examine the Biblical story that inspired the canvas, before turning to the painting’s reception and circulation. The final third of the chapter situates Brocos and Redenção in the interior of Rio de Janeiro state, a physical and social landscape quietly transformed by slave emancipation. Throughout, we probe the history of interpretation that has been reluctant to interrogate what is to be made of the Black characters in the canvas and how Brocos, whose contact with Afro-Brazilians began in the 1870s, during his student years, and intensified after 1890, drew from direct contact with the formerly enslaved to paint his enigmatic portrait of bondage redeemed.

Brocos and the Curse of Ham

Redenção de Cã takes direct inspiration from a strange episode in the Book of Genesis, chapter 9. After the Great Flood, Noah gets drunk on wine and falls asleep naked in a tent. The patriarch’s youngest son Ham reports the scene to his older brothers, Shem and Japheth. The two enter the tent and cover their father, making a deliberate effort to avoid seeing him unclothed. Once awakened from his drunken slumber, Noah – enraged – condemns Ham’s son Canaan to servitude. Gen. 9:25 reads “Cursed be Canaan! The lowest of slaves shall he be to his brothers.”Footnote 11 The following passages describe Canaan’s miserable fate and the divine grace extended to the descendants of Shem and Japheth.

The curious episode at Noah’s tent invites questions that have challenged theologians, Biblical historians, and the faithful since antiquity. What was the offending nature of Ham’s transgression? How could Noah be so intemperate? Why is the seemingly innocent Canaan condemned for the sin of his father, Ham? There have been no clear answers to such questions, but Jewish, Christian, and Islamic theologians of the ancient and medieval worlds found explanations for human bondage in the Hamitic Curse.Footnote 12 The idea of servitude gradually came to be attached to black skin, and a scriptural curse of enslavement without explicit reference to skin color evolved into a sacred plan for Black captivity and, more specifically, the subordination of corrupt Africans descended from Black Ham to the righteous non-Blacks who descended from Ham’s brothers.Footnote 13 In the age of the transatlantic slave trade, the contorted story of Noah, Ham, and Canaan – with occasional admixtures of other figures from Genesis, including Adam and Eve’s son Cain and Canaan’s eldest brother Cush – figured in numerous tracts on bondage and interracial relations. By the nineteenth century, the Curse had come to serve as a useful agitprop for justifications of Black enslavement and white slaveholding throughout the Atlantic, most notably in the United States South.Footnote 14

Although the transatlantic slave trade to Brazil endured into the 1850s and Black bondage was not abolished until 1888, the Hamitic Curse had a weak uptake in Portuguese America. Nonetheless, variations on the Curse circulated in nineteenth-century Brazil. Castro Alves’ poem “Vozes da África” (“Voices of Africa,” 1868) and Perdigão Malheiro’s monumental tract on slave law A escravidão no Brasil (Slavery in Brazil, 1866–1867) both reference the sorry fate of Ham and his descendants.Footnote 15 Debate on the floor of the Brazilian Parliament and published traveler accounts of the era invoked the Curse as shorthand for Black enslavement.

Brocos’ motives for selecting the Curse for his submission to the 1895 salon are thinly sourced. Press coverage registered merely elliptic references to the backstory of the canvas; Brocos did not exert much effort documenting his creative process. There exist, however, some suggestive clues. It’s well known that Brocos painted from life models, and he knew people of color to be integral to the fine arts (including the modeling stand) since his days as an art student in the 1870s.Footnote 16 His ongoing association with Black models is confirmed by Carlos de Laet, whose write-up of the 1895 Salon includes the snide observation that Brocos was the subject of idle gossip when seen traveling with an aged Black woman who served as his model.Footnote 17 Many years later, memorialist Rodrigo Otávio Langgaard de Meneses (1866–1944) wrote that his fair-complexioned son was the model for the child at the center of the composition.Footnote 18 The remarks about models from contemporaries establish the context in which Brocos painted and often offer a vantage point onto the social networks that Brocos accessed to construct a pictorial narrative of racial types.

The appeal of whitening was undoubtedly in the air in early Republic, and the newly reorganized national art school, which Brocos joined in its infancy, was in dialogue with the era’s scientific and policy debates on race. In early January 1895, Brocos’ contemporary Carlo Parlagreco referenced preliminary drawings exhibited in private that might soon develop into “a true work of art that will personify, set within our milieu, one the most incontrovertible principles of American Ethnology.”Footnote 19 That passage certainly lends credence to the notion that Brocos was familiar with ongoing debates on racial types and mixture, though it does not speak directly to Brocos’ relation to any given strain of racial thought. Galician scholars Fernando Pereira Bueno and José Sousa Jiménez situate the canvas within a wider post-abolition immigration policy that was resolutely anti-Black.Footnote 20 Yet the artist’s specific attachments to immigration policy remain opaque, and it’s difficult to corroborate the implication that the anti-Black undercurrents of Brocos’ social utopia novel Viaje a Marte (1933) directly inspired a painting completed nearly forty years prior.Footnote 21

Our best clue to the painting’s inspiration is its obvious Biblical referent, which can be substantiated in a brief passage in A questão do ensino (1915).Footnote 22 Sometime during his studies at the Imperial Academy (April 1875–April 1877), Brocos was assigned the theme of Noah’s drunkenness for an exercise about canvas composition.Footnote 23 That student work (and the Academy records for that period) have been lost, but it can be confirmed that the Hamitic Curse figured directly in Brocos’ artistic vocabulary. In a more general sense, there is ample evidence that Brocos took inspiration in Biblical subjects, including his 1883 prize-winning scene of Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well (Genesis 24) and La adoración de los pastores, a Nativity scene. A professed admirer of Doré’s illustrated Bible of 1866 (a work that contained the plate “Noah Cursing Canaan”), Brocos was conversant with dramatic interpretations of Biblical passages.Footnote 24 Although Redenção is most often treated as a secular work in dialogue with nineteenth-century “scientific” thought, Biblical characters and themes surely animated the artist.

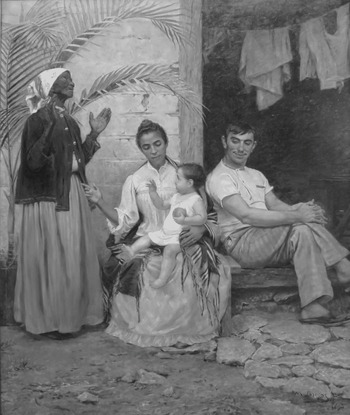

Biblical inspiration notwithstanding, the work exhibited at the 1895 Salon stepped far outside Scripture, shifting attention from the scene of drunken and angry Noah cursing Canaan to an arresting extratextual allegory of redemption. The drama at the tent is relocated to the threshold of a rustic house bathed in rich illumination and shadows. To the left of the canvas stands an elderly, dark-complexioned woman, her bare feet on unpaved ground. She wears a long-sleeved, dark brown coat with tattered sleeves, a long plain skirt, and a stamped headscarf. Palm fronds gently arch over her head, adding an Orientalist touch to a scene that is non-specific in place and time.

Next to the aged Black woman sits a younger adult female figure, of fine features and brown skin tones, who points with her right hand to the old woman while looking at a child sitting in her lap. A golden wedding band is visible on the younger woman’s left hand that emerges from a striped blue shawl draped over a pale pink blouse with tiny polka-dots. The tip of a blue shoe peeks out from under a long, patterned skirt that falls just above the last of the stone pavers. The seated woman gently supports a chubby young child, perhaps one-and-a-half years old, dressed in a stark-white tunic with delicate blue ribbons adorning the sleeves and lacy neckline. The fair-complexioned toddler holds an orange in the left hand, modeling the familiar posture of Christ and the Orb.Footnote 25 The young woman and child each motion toward the old Black woman, who raises her hands to the heavens as if in thanks for a gift of divine grace. To the far right, seated and leaning against a wooden doorframe, is an adult male, Mediterranean in facial features and coloration, who looks on dispassionately with a slight smile. Hands clasped over the right knee, the muscular man is dressed in an off-white short-sleeved shirt, checked trousers, and simple leather footwear. In the shadowy background inside of the humble dwelling appear a table and a line of laundry hanging out to dry. Although the home’s darkened interior is in sharp contrast to the child’s stark white covering, the scene emanates warm luminous gradient tones of sunlight and earth, rough-hewn wood and stone, and weathered sunbaked clay.

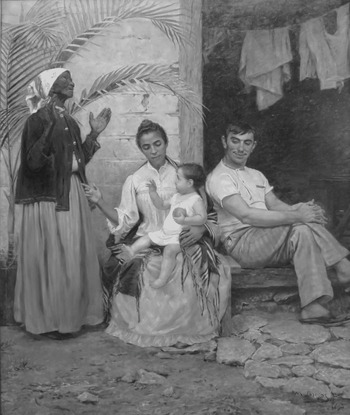

Redenção is a fine example of Brocos as colorist, but in its compositional choices the painting might be more readily associated with the painter’s lifelong interest in the stages of the human life cycle. Titles such as Retrato de anciana (Portrait of an Aged Women, 1881), Retrato de joven (Portrait of a Youth, n.d.), Niño con piel de cordero (Child in a Sheepskin, n.d.), El joven violinista (The Young Violinist, n.d.), Niña cosiendo (Girl Sewing, n.d.), and Albores (Beginnings, ca. 1888) demonstrate the affinity for capturing subjects of various ages that developed in the years before Brocos took up the Ham canvas. The painter had also developed an eye for themes of intergenerational dynamics. The prime example (see Figure 13.2) is Las cuatro edades (The Four Ages, 1888), also known as Las estaciones (The Seasons). Executed in Rome, two years prior to Brocos’ relocation to Rio de Janeiro, Las cuatro edades shared with Redenção the composition of a humble setting where four rustic individuals of progressively increasing age, from the infant to the elderly, enjoy a moment of domestic intimacy. A similar four-figure composition of unknown dating, La familia (The Family, n.d.), featured a young child sitting in his finely dressed mother’s lap reaching out to another adult female, perhaps a nursemaid, while a bearded male adult in a workman’s apron looks on.

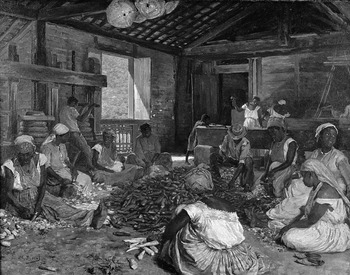

Engenho de Mandioca (Manioc Mill, 1892), Brocos’ most significant work of intergenerational relations painted prior to Redenção, is in direct dialogue with the 1895 redemption allegory (see Figure 13.3). The 58.6 × 75.8 cm canvas was first exhibited at a break-out show organized at the national fine arts school about two years after Brocos relocated from his native Galicia, Spain, to take up residence in the Brazilian capital. In a remarkable shift in Brocos’ aesthetic attentions from the European peasantry to Afro-Brazilian folk people, Engenho presents an assembly of young and old Black females seated on an earthen floor in a large tiled-roofed structure familiar to the Brazilian interior. In the background stand more adult women as well as an adult male and a boy of perhaps ten years. The main drama unfolds as these figures peel, grate, press, and cook cassava tubers to make manioc flour. At the work’s first public exhibition, Brazilian poet and art critic Adelina Amelia Lopes Vieira favorably noted how the painting included a wide range of figures – the older woman exhausted by work, a proud mother and her nursing infant, a smiling Black woman, a youth at work.Footnote 26 Engenho de Mandioca was, undoubtedly, an important rehearsal of a major canvas about intergenerational family relations.

In its close attention to a play of light and shadow, the material culture of rural life (woven baskets, wood furnishings, slip-on footwear, a straw hat), and the exuberant landscape that surrounded Guanabara Bay (referenced through the open window on the left), Manioc Mill sealed Brocos’ standing as a respected artist of the national fine arts school. The careful detail of the facial expressions and body positioning of the Afro-Brazilian laborers signaled Brocos’ quick study of an adopted homeland and its lifeways of rural production. The praise of Gonzaga Duque Estrada (1863–1911), an influential critic of the period, was especially important for establishing Brocos as an interpreter of Brazilian social types. Gonzaga Duque proclaimed Brocos a “pintor de raça,” a subtle word play on the painter’s natural-born talents as well as his innate aptitude to paint “race,” an obvious code word for the Afro-Brazilians who filled Engenho de Mandioca and the actual manioc mills of the late nineteenth-century countryside.Footnote 27

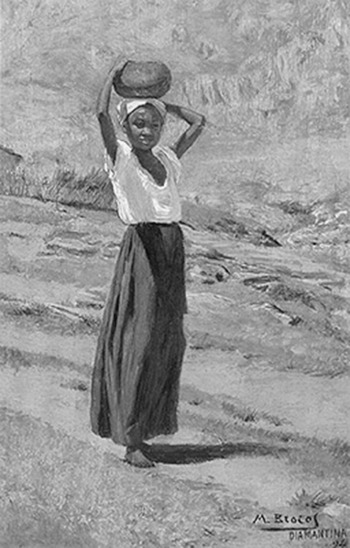

Boosted by accolades from the likes of Gonzaga Duque, Brocos intensified the embrace of themes and tones that prominently featured Afro-Brazilians. A 1893–1894 trip to Diamantina, a colonial-era town located in the north-central part of Minas Gerais state, was formative for fixing a Black Brazilian cast on themes of rural peoples previously rehearsed in northern Spain and southern Italy. In Diamantina, Brocos experienced the daily life of a mountainous region deeply rooted in the experiences of people of color living among spent mining fields. His earlier studies of the Iberian and Italian peasantry informed new works on Afro-Brazilian countryfolk. Evocative titles from the trip exhibited at the 1894 salon include Crioula de Diamantina (Black Woman of Diamantina), also known as Mulatinha (Young Mulata) (see Figure 13.4), and Garimpeiros (Miners).

In short, Brocos was well rehearsed in a number of the thematic elements to be assembled in Redenção prior to taking up the preparatory work for the 1895 Salon. In addition to the interplay of age, family, and agrarian lifeways, he experimented in the tonalities of the soil, flora, and natural light of the Brazilian countryside. Brocos had acquired the critical respect of a “painter of race.” The prize-winning canvas of 1895, nonetheless, demonstrated important innovations in the strategic choices of subject. Chiefly, Redenção elevated the local conditions of an interracial post-emancipation society to the center of artistic expression. The freshness of slave emancipation and the destruction of captivity were the subtext for a composition ostensibly about the “redemption” of the familial order mysteriously violated in Noah’s tent.

In this perspective, the Biblical Curse of Ham is wholly upended. In the place of an infuriated Patriarch damning his grandson to bondage, a pitch-black woman stands before a male/female couple and their infant child. The young woman wears a wedding band, underscoring an observation made by various critics of the 1895 salon that the group forms a family.Footnote 28 Rather than Ham crouching in fear of his father’s scorn, the adult figure in the center of the canvas – a young woman of color – sits upright and calmly points toward her elderly mother (a figure Azevedo described as “the old African macerated by captivity”), who raises her hands in thanks for the deliverance of a self-evidently sinless grandchild. Noah’s enigmatic curse of servitude and the degraded Blackness that came to be attached to it had been redeemed into sacramental interracial marriage and a fortunate, legitimate birth.

Reception, Circulation, and Repercussions

The Rio intelligentsia registered concerns about various technical and thematic elements in Redenção de Cã when the painting was first publicly exhibited in 1895. Nonetheless, the canvas was generally well-received by influential voices in Brazilian letters. Playwright Arthur Azevedo (1855–1908) declared Redenção a “national painting” (o seu quadro é um quadro nacional).Footnote 29 Poet Olavo Bilac (1865–1918) declared it to be a “most beautiful grand canvas.”Footnote 30 Novelist Adolpho Caminha (1867–1897), though underwhelmed by the painting’s qualities, conceded that “it has been a long time since a work has received so much praise.”Footnote 31 The favorable remarks from these influential writers bolstered efforts by Brocos’ contemporaries at the ENBA to have the work acquired for the national collection.Footnote 32 Such praise also guaranteed that Brocos would not be treated as an artist-traveler but rather as a painter of “national” focus.

In its quick passage from the salon to the national art collection, Redenção entered into the wide-ranging conversations about interracial relations in post-emancipation Brazil. That conversation followed two complementary registers. On the first, the central scene was taken to be an illustration of the fortuitous path toward racial “improvement” via miscegenation. Azevedo made the explicit case that an alternative title could be “The Perfection of the Race” (O Aperfeiçoamento da Raça).Footnote 33 A decade later, Sylvester Baxter, an American newspaper writer from Boston passing through Rio, echoed Azevedo, characterizing Redenção as a fine allegory of “the development of the Brazilian race.”Footnote 34 These statements conditioned the long line of interpretation about the painting as an allegory of racial “improvement” through the science of race-mixing.

On the second register, Redenção furthered an imaginary of the Black race’s disappearance into whiteness. Carlos de Laet characterized the painting as “a genealogy in which by two generations the Ethiopic element becomes white. An old Black woman had a mulatinha daughter who shacked up with a rube [labrego] and gave birth to a child that exhibits all of the characteristics of the Caucasian race.”Footnote 35 Adolpho Caminha disputed the implication that whitening might be accomplished in just three generations, but the author of the contemporaneous Bom crioulo (The Black Man and the Cabin Boy, 1895) manifested confidence that the end product of miscegenation would spell the end to the Black race in Brazil.Footnote 36

Most famously, João Batista de Lacerda (1846–1915), the prominent anthropologist and director of the Museu Nacional, included a reproduction of the Brocos canvas in the French-language print edition of his presentation to the Universal Races Congress held in London in July 1911.Footnote 37 Lacerda’s paper, “The Métis, or Half-Breeds, of Brazil,” envisioned the progressive disappearance of the Black race and the victory of civilized whiteness over darkness. Although Lacerda made certain concessions for the positive contributions of mixed-race people, the “science” of his presentation was patently anti-Black. The caption to the accompanying illustration encapsulated the message of Black disappearance, reading: “Black becomes white, in the third generation, through the mixing of races” (“Le nègre passant au blanc, à la troisième génération, par l’effet du croisement des races”). Such a postulation was hotly disputed in Brazil, and official census numbers and racial self-identification disproved the argument that the Black race was disappearing into whiteness.Footnote 38 Nonetheless, the caption was consistent with the appeals to racial “improvement” through whitening that had circulated since 1895 and framed what was to be made of Redenção for later generations.

The Brazilian eugenics movement, and its attendant dim view on the racial health of nonwhites, began to lose luster in the 1930s, a period of great ferment when artists and intellectuals, social thinkers, popular musicians, and politicians turned away from the fantasies of Black erasure.Footnote 39 Redenção, accordingly, lost much of its relevance and retreated into relative obscurity. Between 1937 and the 1970s, the canvas continued to hang in the National Museum of Fine Arts, but mention in the popular and arts press most often came in relation to Engenho de Mandioca, elevated to the status of Brocos’ most important work.Footnote 40

When the ideology of “racial democracy,” consolidated in the postwar period, faltered in the mid-1970s, Redemption grew increasingly discredited as a shameful example of the long history of racial prejudice in Brazil. Brocos himself was generally spared charges of personally harboring racist beliefs, whereas his canvas was singled out as a deeply offensive emblem of white supremacy in a so-called racial democracy. In 1978, Afro-Brazilian activist Abdias do Nascimento (1914–2011) condemned the painting for its “pathological desire, aesthetic and social, of the Brazilian people to become white, imposed by the racist ideology of the dominant elite.”Footnote 41 The arts world was less openly hostile to the canvas, but in an influential reference work on visual arts published in 1988, José Roberto Teixeira Leite characterized the painting as “one of the most reactionary and prejudiced of the Brazilian School.”Footnote 42

North American academics played a central role in fixing the transnational repudiation of Redenção. Thomas Skidmore’s pioneering Black into White (1974) situated the painting as an accessory to Lacerda’s 1911 presentation in London. Skidmore’s observations were picked up by Brazilian anthropologist Giralda Seyferth and North American historian of science Nancy Leys Stepan, both placing the canvas in the wider history of eugenics and anthropological sciences.Footnote 43 Scholarly monographs by Werner Sollors, Teresa Meade, Jennifer Brody, and Darlene Joy Sadlier also touched on the canvas’ racist context and content. Several textbooks for the North American higher education market – by E. Bradford Burns, John Chasteen, Theresa Meade, Kristin Lane and Matthew Restall, and Henry Louis Gates – popularized the reading that the painting is an exemplar of the ideology of whitening.Footnote 44 Online journalism and most especially social media have extended the work of these academics, repeatedly presenting Redenção as an illustration of the persistence of anti-Blackness in Brazilian racial relations.Footnote 45 Redenção has become shorthand for Brazilian racism.

Redeeming Ham, Once Again: Brocos and the Destruction of Slavery

In a 2011 piece of popular history, anthropologist Giralda Seyferth summarized the enduring understanding of Redenção as a symbol of scientific racism and whitening: “O futuro era branco” (The future was white). The fair-complexioned child at the center of the canvas – white, young, and innocent – is the primary symbol of that white future. The limitations of such an interpretation include the casual disregard for one of the most self-evident elements of the painting: the velha preta (the old Black woman), a figure who evoked a very recent past of slavery’s destruction in the largest and most enduring slave society of the Americas, as well as her mulata daughter, a symbol of the experience of the children of slave mothers born in the last decades of the slave regime. In privileging the white future, interpreters place the agency of dynamic change on the male white figure and his even whiter child, leaving the elderly Black woman and her light-skinned daughter to be little more than bit players, objects of the voyeuristic (male) gaze. The prevailing inattention to these women as protagonists of their recently won freedom is striking, as Brocos’ biography and artistic output in the 1890s indicate that he held a fascination with the formerly enslaved, especially women.

In this section, I consider how those stand-ins for the descendants of Ham – embodied in the two female characters, one allegorizing the Black African and the other the Brazilian-born mulata – are to be read as active agents in the reversal of the Hamitic Curse and the “redemption” of the Brazilian race. I also explore how Brocos acquired the knowledge to situate women of color as the central actors of an image that throws off the shackles of Black captivity.

The approach is informed by two provocations by Brazilian art historian Roberto Conduru. The first departs from the proposition that people of African descent were constituent elements of the progressive stages of modernization in Brazilian fine arts, from the latter decades of the nineteenth century through the 1930s. People of color were artists proper, representing themselves and the experiences of Blackness in a society ridding itself of its slave past.Footnote 46 Simultaneously, Conduru asserts, Afro-descendants were the object of study and representation of white artists.Footnote 47 Brocos and Redenção fall into the latter category. Linking Redenção to other paintings by white artists that feature noble Black subjects (e.g., José Correia de Lima, Retrato do Intrépido Marinheiro Simão, ca. 1854; Belmiro de Almeida, Príncipe Obá, 1886; Pedro Américo, Libertação dos Escravos, 1889; Antonio Parreiras, Zumbi, 1927) and well as commonfolk of color (e.g., José de Almeida Junior, Negra, 1891; Lucilio de Albuquerque, Mãe Preta, 1912), Conduru plots a fine arts tradition that does not conform to the aspirations of unidirectional whiteness and whitening. Conduru comes to no definitive conclusions, but his interventions invite us to look at and to look for the origins of the protagonism of Blacks (what he terms “Afro-modernity”) in the fine arts (and, implicitly, in multiracial Brazilian society).

The second inspiration draws from Conduru’s contextual reading of Brocos’ Mandinga. First exhibited at the 1892 one-man show organized by the national fine arts school, Mandinga (then known as Feiticeira, or Sorceress) was re-exhibited alongside Redenção de Cã at the 1895 salon (see Figure 13.5). The principal subject is a seated dark-skinned sorceress who sits before a serpent, while another woman of olive complexion leans on a table. The eyes of both women appear closed. Conduru asks not merely what is going on in the image but how Brocos might have come to know about Afro-Brazilian religion and its practitioners. “Contrary to what one might think, this image could be quite faithful to what the artist would have encountered in the streets of the Federal Capital [Rio] at the time, especially if it is compared alongside the observations of João do Rio [author of As religiões do Rio (The Religions of Rio), 1906] and Nina Rodrigues [author of O animismo fetichista dos negros baianos (Fetishism among the Blacks from Bahia), 1896].”Footnote 48

In making a case for a fidelity to the “real” and the documentary, Conduru’s method calls for a closer consideration of what Brocos knew of Afro-Brazilian life in the post-emancipation context. He challenges the reader to consider the artist’s ideological and visual education in the laboring and spiritual lives of women of color who formed part of urban daily life in Brocos’ adopted homeland. Conduru does not discard the notion that the social milieu in which Mandinga circulated was rife with anti-Black racism, but he does speculate on the ambiguity of intent and an openness to reading Brocos’ other works as products of the artist’s direct interactions with laboring people of color who become objects and subjects of fine-arts production. Conduru’s suggestive thoughts lead us to explore what Brocos knew of slave “redemption” and how that knowledge informed his artistic output.

The reader is to be reminded that Brocos himself registered precious little about the inspiration for Redenção; any argument about his racial thought draws largely from indirect evidence and imputed motivation. Posthumous interpreters, nonetheless, help fill in the gaps. In the introductory essay to the catalog of a 1952 retrospective organized by the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, J. M. Reis Junior said of the canvas that “[it] raises the issues of an artist concerned with a theme of social import.” In 1977, Quirino Campofiorito, another of Brocos’ former students, wrote of the painting: “With a certain touch of humor, the fusion of the races in Brazil develops in the passage of four well-placed characters. Both paintings [Redenção and Engenho de Mandioca] speak to the social conditions that stimulated the artist’s sentiments.” In an early draft to the preface of the catalog for a 1952 retrospective, MNBA curator Regina Real directly raised the artist’s engagement with thorny questions of race and color in Brazil: “[Brocos] approached difficult racial themes [temas difíceis raciais] in Redenção de Cam and the evolution of age in Estações [Las cuatro edades].” The catalog’s final printed version read slightly differently: “The Brazilian setting, the landscapes, the racial types, take hold of the artist and he reproduces them with interest and fidelity. We have family portraits of [son] Adriano and [wife] D. Henriqueta, scenes of Soberbo and Teresópolis, and the Blacks and their tribulations of liberty” (os negros e seus problemas de libertação).Footnote 49 With a certain echo of Duque Estrada’s 1892 characterization of the pintor de raça, Real’s attention to Brocos’ relationship to temas difíceis raciais and Blacks’ problemas de libertação pointed to the very proximate but generally overlooked relations to emancipation and freed peoples that the painter knew personally.

That experience began with the Free Womb Law (September 1871), passed eight months before Brocos first arrived in Brazil for a five-year period of study and freelance work as an illustrator. The law had envisioned a slow, largely natural process of abolition that would stretch into the twentieth century. Instead, prolific litigation and radical antislavery mobilizations progressively rendered gradual abolition untenable. Living in Rio just prior to the emergence of popular abolitionism, Brocos accompanied the demographic decline and geographic redistribution that set captivity on an inexorable path to obsolescence. Yet the demise of slavery was hardly sudden, and students including Brocos continued to interact with current and former slaves throughout their daily lives as residents of Brazil’s largest slave city. Their professors grappled with disentangling the Academy from a culture of slaveholding that had been part of the institution’s foundational years.Footnote 50 Outside his formal studies, Brocos worked within a world of print that became deeply engaged with the abolitionist cause, notably in the work of the Italian immigrant Angelo Agostini.Footnote 51 In short, Brocos had opportunity to preview the contours of the “tribulations of liberty” that fueled the collapse of Brazilian slavery during Brocos’ extended absence from Brazil between 1877 and 1890.

Such contours conditioned the post-emancipation social landscape in all corners of Brazil, including a reorganized national arts school that Brocos joined as teaching faculty in 1891. This acclimation to post-abolition Brazil took place within a social network that linked Brocos’ family residence in Rio’s Catumbi neighborhood to the Fazenda Barreira do Soberbo, a rural estate located in Guapimirim, a small hamlet in the interior of Rio de Janeiro state, near Magé. Located in the upper reaches of the Guanabara Bay watershed, Guapimirim (1890 population: 3,414) attracted sculptor and director Rodolpho Bernardelli (1852–1931) and his brother, painter Henrique (1857–1936), to make an artists’ retreat at the foot of a verdant escarpment leading to the mountainside town of Teresópolis. Shortly after 1891, Brocos joined the Bernardellis as a frequent visitor to Guapimirim (see Figure 13.6).

In the shadow of the towering pinnacles of the Serra dos Órgãos, Brocos shared with the younger Bernardelli and other artists, including the Italian-Brazilian landscape painter Nicolau Antonio Facchinetti (1824–1900), an idyll of temperate air and spectacular scenery. Late in life, Brocos described his retreat on the Soberbo River as a place of great inspiration, where isolation and solitude released a creative spirit often held up by the interruptions of everyday urban life.Footnote 52 His artistic output, especially in his first decade of residence in Brazil, confirms his later statements about the inspiration drawn from the clean air, light, dramatic landscape, and flora of the Soberbo watershed. An untitled study of the Teresópolis countryside and Dedo de Deus (both exhibited 1892), Paineira and Mangueira (Silk Floss Tree and Mango Tree, ca. 1900), Cascata na Barreira do Soberbo (Waterfall at Barreira do Soberbo, 1903), and Recanto do Soberbo (Soberbo Retreat, ca. 1903) document the inspiration taken from a grand natural landscape located within a half-day’s train ride from Rio de Janeiro yet situated far from the bustling city’s rapid social and economic modernization.

In Barreira and environs, Brocos also developed an intimate relationship with a human landscape deeply marked by slavery and its recent destruction. In 1895, the painter married Henriqueta Josepha Dias (1859–1941), heir to a large estate adjacent to the Soberbo River established by her father, Henrique José Dias (1819–1904). A one-time model plantation for the cultivation of cinchona (quina), an Andean tree used for the manufacture of antimalarials, the 1,500-hectare farm had been battered by declining yields and the unraveling of the slave regime throughout the interior of Rio province.Footnote 53 When Brocos first arrived in the vicinity of his future wife’s estate, around 1891, cinchona cultivation had given way to manioc and other basic staples of the rural diet that also had markets in urban centers. Black family subsistence labor was at the center of agrarian production in and around the post-emancipation Barreira estate.Footnote 54 Brocos was clearly smitten with this laboring landscape turned over to manioc, and his first major work painted in Brazil, Engenho de Mandioca (1892), is a testament to his rising attachments.

In the absence of a comprehensive catalog of Brocos’ opus, the titles, media, and dating of many of the works produced in this period cannot be treated as definitive, but it is clear that Brocos’ visual vocabulary of the Afro-Brazilian post-emancipation rural peasantry sharpened in Soberbo between 1891 and 1895. Engenho depicts Black peasant families working manioc in a setting that looked very much like post-emancipation Guapimirim. Registries of titles of contemporaneous works – Alegria, Libertação dos Escravos (Happiness, the Liberation of Slaves) and Marcolina, Ex-Escrava da Barreira (Marcolina, Ex-Slave of Barreira) – prove that Brocos circulated among the former slaves of his father-in-law’s estate.Footnote 55 The portrait of Marcolina and a contemporaneous work, Vista da Senzala da Barreira do Soberbo (View of the Slave Quarters of Barreira do Soberbo, 1892), present direct evidence that Brocos came to know the faces of older Black women and the post-emancipation built environment of the daub-and-wattle walls, earthen floors, and open windows featured in Redenção. Although these obscure works are now known solely in catalog listings, several of Brocos’ contemporaries observed how Redenção was exhibited alongside several other works that featured Black female figures. That is, the notorious allegory of a racial future was shown alongside documentary explorations of present Brazilian “reality.” The titles, moreover, provide important clues that Brocos developed his work in dialogue with a recent history of Black women’s struggles to redefine their legal, family, and work identities in the context of slavery’s demise around Barreira.

The demographic history of Magé, the township in which the Fazenda Barreira was located, adds additional context for understanding the realities of rural life that Brocos studied in the early 1890s. Chiefly, Marcolina’s counterparts had largely conquered freedom years before final abolition, without miraculous intervention. In the 1872 slave census mandated in the Rio Branco Law, 312,352 slaves were counted in Rio province. That population continued to grow, via the internal trade and natural growth, to 397,456, registered on September 30, 1873. Yet, by the new census completed on March 30, 1886, the number of enslaved in the province had declined by more than half, to 162,421. In Magé, the rate of decline had been much more pronounced. As of September 30, 1873, there were a total of 8,268 slaves (4,658 males and 3,610 females) counted. Between 1873 and 1883, 274 additional males and another 286 additional females had entered the township, whereas 2,481 males and 1,978 females had departed. With the deaths of 658 men and 764 women, and the emancipation of 135 men and 178 women, the municipal slave population on June 30, 1883, stood at 2,941 (1,658 males and 1,283 females). As of March 30, 1887, that figure had continued to drop to 1,244 (651 men and 593 women), about 15 percent the figure for 1873.Footnote 56 This precipitous drop in captives – in absolute and relative terms – took place largely in the absence of assistance from the emancipation funds, established under the Free Womb Law of 1871, and other gradualist measures associated with the legalist path to abolition that culminated in the Golden Law of May 13, 1888.

This demographic transition from slavery to freedom also transpired without the presence of white immigrants, who were disinclined to settle among poor rural Blacks. In a 1898 response to a questionnaire submitted by the central government to the municipalities of Rio state, the Municipal Chamber of Magé responded: “The population totals 26,300 inhabitants, almost all nationals (Blacks, whites, and their mixed offspring); there are few foreigners and those that are here are European.”Footnote 57 Local leaders were undoubtedly open to foreign immigration, informing the state secretary of public works of their fair weather and conditions favorable to white immigrants, preferably from Portugal and Italy. Nonetheless, the southern European immigrant played a minor role in the social formation of the Rio state interior near Guapimirim in the period contemporaneous to the execution and exhibition of Redenção.

The absence of white immigration in the agrarian landscape transited by Brocos offers some corrective to the notion of agency that is embedded in a wide strain of interpretation about Redenção that presents the painting as a didactic prescription for the “improvement” of the Brazilian race through the reproductive union of immigrant male laborers and Brazilian mulatas. Whereas critics like Azevedo and Caminha saw the male figure as the transformative actor, the demographic data tells us that rural slavery in Magé was largely undone without new white arrivals. These demographic indices underscore the fact that the countryside that Brocos came to know after 1890 was populated by agriculturalists who had experienced abolition as a gradual and local process, rather than some abrupt end to an enduring labor system undone by humanitarianism, providential fortune, or foreign arrivals. It was largely a Black story.

The specific resonance of demographic trends in the lives and life arcs of the former slaves and free people of color at Fazenda Barreira shall require close reading of property and civil registries, particularly those found in local archives in Guapimirim.Footnote 58 A spectacular find would be the registry of Marcolina’s manumission and the family dynamics involved in her decision to remain at the Fazenda Barreira, quite possibly to live in the former slave barracks that Brocos would later paint. But even the more mundane records of the meia-siza, a tax on sale of domestic-born slaves, documents the lives of slaves engaged in rural work (escravo de roça), domestic service, boating, and skilled trades including tailoring and stone masonry.Footnote 59 The surviving records, corresponding to the years 1863 to 1883, held at the Arquivo Publico do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (AEPRJ), heavily favor transactions of single Brazilian-born ladinos (described as crioula/o; de nação; natural da província) matriculated in the slave census of 1872. However, the APERJ also included records of the sale of slave mothers accompanied by their children. For example, in 1873 the tax was levied on the sale Leopoldina, a thirty-five-year-old Black agriculturalist, unmarried, and her five-year-old son, Belmiro.Footnote 60 By the time Brocos came to know the region of Barreira, Leopoldina would have been in her mid-fifties, and Belmiro would have been an adult. Both would have been manumitted for some time, perhaps as long as two decades. Nonetheless, both would bear with them the experience of slavery and its often brutal dynamics of sale and dislocation, and also the dynamics of abolitionism, including the prohibition against the break-up of slave families imposed in the Free Womb Law of 1871.Footnote 61 Such experiences might have influenced what Brocos came to see and render in the faces of liberty.

The meia-siza records are among the many registries that should yield further insights into the life experiences of the caboclinhas, morenas, mulatinhas, crioulas, and other racialized and gendered personages in Brocos’ artistic output who, under close scrutiny, bear the marks of a close, intimate history of the recent slave past. Future research will yield more granular understandings of the transitions between bondage and liberty in the rural hinterlands of Guanabara Bay and their translation into the visual output of Brocos and other artists who ranged far beyond the Academy. Nonetheless, the regional demographic evidence and comparative cases from other regions of Rio province already demonstrate that the children of Ham were “redeemed” from bondage within Black spaces, in Black families, and between Afro-Brazilian women and their children.Footnote 62

Conclusion

Close attention to the commonly overlooked conditions under which Brocos conceptualized and then executed Redenção offers some tantalizing prospects for documenting the Black agency that remade the countryside allegorized in the canvas. Alongside the unmistakable resonance of embranquecimento embraced by a long line of thinkers from Artur Azevedo to João Baptista Lacerda (and critics such as Abdias do Nascimento), we must be attuned to the voices of formerly enslaved peoples who also give meaning to the canvas. The gendered dimensions of these voices are strong, and there is special attention due to rural women of color. The womb as a passage to freedom is an especially important frame for reading an allegory of reproduction; it is directly relevant to a painting completed twenty-four years after the passage of the Free Womb Law – about the same period of time that might be ascribed to the age of the young mother at the center of the canvas.

With these working propositions, we acquire a set of tools to look anew at the Brocos canvas. Black women, rather than white men, help coproduce the “redemption” of the slavish sons of Ham. Although an allegorical appeal to whitening is unmistakable (and well reinforced in a long history of reception), Brocos’ vision for the Brazilian race may not be so exclusively white. Without doubt, the elderly Black woman – by far the most imposing and active figure – is not to be easily erased from the post-emancipation order. A 2018 temporary recontextualization of Redenção, exhibiting the canvas among dozens of works about and by Afro-Brazilian artists held by the Museu Nacional de Belas Arts, suggestively relocates the female figure deep within a Black milieu that can be read for meanings constructed outside the white and whitening gaze of the historical permanent exhibition (see Figure 13.7).

In a reappraisal of Redenção that considers the real alongside the imaginary, the dramatis personae of the story remain largely the same as those seen by the apologists for whitening, but the dynamism of the view shifts from the right of the canvas to the left, from the figure of the largely passive white male toward the elderly Black woman – a former slave, possibly an African. Her posture may have less to do with the awestruck wonder for the birth of a “white” grandchild purportedly fathered by the immigrant son-in-law and more to do with the culmination of a long process of securing the freedom of herself, her offspring, and her race. As we look yet again at the canvas, the dark specter of racial sciences and a whitened future remain, but those “tribulations of liberty” and the alegria of slave emancipation that Brocos came to know intimately animate our interest in this enigmatic allegory of history-telling and race-making in Brazil.