My passport says that I am a citizen of India and my place of birth is Allahabad, a place that no longer exists. It is now called Prayagraj.

Allahabad – or Ilahabad, as the natives pronounce it – was home to my maternal grandmother. The city emerged on the banks of the Sangam, the confluence of the rivers Ganga and Yamuna. Millions of people come to witness this confluence. If you rowed far enough into the water, you could actually witness the mingling of distinct streams of water, each a different hue. Sangam is also a concept that was spread across the lands watered by these rivers. What was called the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb was a confluence of Hindu, Muslim, Christian and other resident cultures, each of them fed by half a dozen streams of thought and ritual.

Allahabad was once called the Oxford of the East. It is no longer called that either. In its rechristening and in the dissolution of its intellectualism is a story of the dismantling of the emotional architecture of one of my ancestral homes.

Prayag was a name for the area around the riverbank where religious mendicants and hermits lived. In the sixteenth century, Mughal emperor Akbar came visiting and, struck by its beauty and serenity, commissioned the creation of a new city called Ilahabas: bas (‘home’) to ilahi (‘the divine’).1 An alternative story is that there already was a settlement in this region named for Alha, a warrior of the Banafar clan whose heroism is written into ballads that have been sung across the countryside for centuries. Whichever version is correct, a fort was built only after Akbar’s visit, and a town sprung up around it.

The area where my family home stands was aligned to the Grand Trunk Road. The dust of civilisations east and west undoubtedly fell off caravans and clung to native limbs and tongues. Still, the town was well described by the word provincial. In the mid nineteenth century, the great Delhi poet Mirza Ghalib had dismissed Allahabad as a ‘desolation where neither such medicine may be had as befits the ailing nor regard for those of rank’.2

If it was not a desolation before, it certainly became one after the uprising of 1857 when Indian soldiers tried to seize control of the fort that had been turned into a military cantonment for the British East India Company. British officials later recorded that even women and children felt ‘the weight of our vengeance’.3 Bholanath Chunder, an Indian observer, wrote, ‘To “bag the nigger” had become a favourite phrase of the military sportsmen’ and that porter or peddler, shopkeeper or artisan were hurried through a mock trial and made to ‘dangle on the nearest tree’.4

Nearly six thousand people were executed. It took three months for eight carts to finish taking down the corpses that hung at crossroads and in marketplaces, and the bodies were thrown into the river Ganga without ceremony. Ilahabas was utterly undone.

A new city – given a new inflection by the British so it became ‘Allahabad’ – was built on the site of eight villages razed to the ground. A high court was established, followed by a university. These developments caused a great spurt of immigration with the need for labourers, servicemen, scholars, lawyers. Among them were my great-grandfather, who worked as a kotwal or police official, and his brothers, one of whom was a doctor. The four brothers lived together with their families in a roomy townhouse that is inhabited even now by at least half a dozen branches of the family, each with its independent family unit. When we visit, we spend a whole day just nipping into each uncle or great-aunt’s room to say hello, and by the time pleasantries have been exchanged, the sun has gone down.

The town itself seemed, to me, to be resigned to its provincial status. An indecisive, stubborn town, slow to change, quick to temper, mannered but unpredictable. I found myself thinking that it is appropriate somehow that one line of my blood came from here. But where precisely?

Hindi writer Gyanranjan has written, ‘the beautiful, affluent, glitzy Allahabad is quite distinct from the poor and crowded older town of the Grand Trunk Road … the town has its kitchen on one side, its dining room and drawing room on the other’.5 I come from the kitchen then, and like all kitchens, it is supposed to be invisible to everyone who can afford not to go there. It is the throbbing heart of the city and is also a ghetto for Muslims, some middle class, many poor.

My mother told me that if I was ever lost in this neighbourhood – and chances were, I would be lost in that tangle of lanes – I should just ask for Dr Mustafa’s house. He was well known because he treated the poor for free. It felt like a tall claim. Tens of thousands of people live here. Who would remember a doctor who’s been dead for decades? But Mom was right. I did get lost, and each time, I’d say Dr Mustafa’s name and was directed to the right house.

Three generations later, people remembered. It had filled me with a shiver of pride. Pride enough that the narrowness of lanes or the obvious mess in the ‘kitchen’ didn’t intrude on my identification with the city. I came from that lane, that house, and from women who protected each other.

My mother found herself alone when she was expecting me. Her own family was abroad that year and there was nobody to look after her. So she came to the care of her Khala-ammi (aunt-mom) as everyone called her, in Allahabad. Married to a cousin, Khala-ammi lived in the same house all her life, stepping out very rarely. She did step out when it mattered, though, like going to the hospital for my birth.

Fragile and dignified in all that I saw of her, it was hard to imagine she would ever break into a run. But, Mom says, it was she who had run with a new-born me in her arms when she noticed an untied and bleeding umbilical cord.

It was in this house that I first came upon the unthinkable: women smoking! They smoked cheap beedis (tobacco in a leaf) instead of cigarettes, and the sight unsettled every cultural nerve in my little body. I’d run to Mom to gasp. She hushed me: it’s a habit from hard times. Hard enough that some members of the family were struggling for food. They had the big house but the boys had no jobs. The women had little formal education. They took on what work they could do from within the house. There were beedi-making units nearby, so they started to roll and a couple of matrons started to smoke.

It is impossible to snap this cord of belonging and memory: the hospital where doctors are not available round the clock, those corridors where I imagine my great-aunt running in a panic, the house where I was swaddled in love since the moment of my birth, where uncles and aunts still look fondly at my face and say You were this small …

*

The poet Arvind Krishna Mehrotra has written that Allahabad is the story of dust to dust. Centuries of isolation suddenly gave way to cosmopolitanism. Less than a century later, its cosmopolitan sheen was gone.

The cosmopolitanism of the late nineteenth century was fuelled by immigration, and nurtured by a string of exceptional academics. Many of the men – and later, women – who taught at the University of Allahabad were deeply invested here. Perhaps they attempted to turn the campus, even the city, into an extension of their inner selves.

In her history of the university, Three Rivers and a Tree, Neelam Saran Gour describes people who went far beyond lectures and examinations. One professor taught arithmetic but wrote monographs on metaphysical subjects, studied Persian and French literature, and could even coach students on anatomical dissections. Another hired a bungalow to ‘house impoverished urchins for whom he engaged a local teacher, and to whom he personally taught English’.6 Another professor drove around town on cold winter nights, carrying blankets for the homeless. The Institute of Soil Science was the result of a large endowment from a professor who was known to wear patchy coats and haggle over the price of potatoes so he could save up for science. There were courses in painting and music. The English and Hindi departments boasted highly regarded poets and critics.

The university’s academic reputation can be gauged from the fact that a physicist of the stature of Schrodinger accepted an offer, though World War II prevented his coming.7 Teachers were ‘figures of awe and glamourous erudition’. Gour’s own teacher described a campus where, if you threw a stone, you were sure to hit a celebrity for, ‘In the high noon of the Allahabad University, teachers were the celebrities.’8

The sun of erudition, however, was setting. Academic standards fell as enrolment rose, thanks to an assumption that a degree would lead to white-collar jobs. As early as 1952, a state-constituted commission recommended that the number of students should never exceed 5,000 when the number was already above 6,000.

The decline was swift and a clear sign was the normalisation of campus violence. It began with freshers being ‘ragged’ by seniors, leading to ‘blue faces, swollen eyes and bleeding noses’.9 Ragging was often a form of brutal assault but such was the approach to intellectual activity, writes Gour, that writing book reviews was deemed a suitable ‘penalty’ for students found guilty of ragging.

Another sign was political vacuity and corruption. A prominent academic, Harish Trivedi, recalled his foray into student politics in the 1970s, with hopes of reforming ‘the rowdy and lumpen Students’ Union, which … seemed to do little else but call for a protracted and violent strike every year, which culminated in a police lathi-charge, with the University then closing down sine die’. His own election brought him to the sad realisation that students had voted for his caste, and not because they shared his hopes for a better academic culture. He also saw his own helplessness: he couldn’t even print a cultural magazine because the budget was embezzled.10

By the late 1970s, rifle-toting bikers tore about campus; bombs exploded off and on. The year I was born, the vice-chancellor stayed off campus and under police protection for several weeks. With riot and rampage, clerks beaten, teachers threatened, mass copying during examinations, 1978–81 were ‘rock bottom’ years. Eventually campus elections were banned. When the ban was lifted, in 2005, the Allahabad High Court again found ‘gross violation of rules’. One candidate was murdered. In 2019, raids in a hostel led to the discovery of materials for making crude bombs.11

As an extension of the self, the campus was no intellectual home. Idealists and oddball geniuses no longer defined it. There is little room for teachers to express ideas. A Dalit professor was recently forced to leave the city after a mischievously edited video surfaced, where he was saying he doesn’t believe in any god. A complaint was filed by a student.12 Instead of standing up for him, the university administration issued the teacher a show cause notice, seeking an explanation as to why disciplinary action should not be initiated.

*

Our attachment to values, cultural symbols, a memory palette is expressed as belonging to a city. A familiar landscape is frozen as a fridge magnet: a bridge, old hand-painted signs, comfort food, poetry. But what if a city is scrubbed of the very things that defined it?

In The Future of Nostalgia, Svetlana Boym writes that contrary to intuition, the word nostalgia comes not from poetry or politics but from medicine. It was studied as a sickness among soldiers, dangerous enough to warrant treatment through leeches, warm hypnotic emulsions, opium and, of course, a return home. Symptoms included confusing real and imaginary events, hearing voices, seeing ghosts. However, Boym writes, ‘Nostalgia is not always about the past, it can be retrospective but also prospective. Fantasies of the past determined by needs of the present have a direct impact on the realities of the future.’13

I have little nostalgia for Allahabad. Certainly, I am not sick for it. But I am nostalgic for its shadow future, for the place it could have become, and for the person I could have been if only the university had continued being the Oxford of the East. I longed for campuses filled with the glamour of erudition, for teachers who set ethical standards as high as academic ones. I longed for that time and place Gyanranjan describes, when people’s faith in poetry was ‘second only to their faith in the heaven-bestowing properties of the water of the Ganges, which they put into the mouths of the dying’.14 This is a fantasy of a past in which I would have been right at home.

Alok Rai, another scholar from Allahabad, has written that meaning is a conspiracy – ‘conspiracy with, or conspiracy against’ – and it is so with names.15 Allahabad was not renamed as much as it was unnamed. There was no reclaiming of a native name. ‘Calcutta’ reverted to its native pronunciation, ‘Kolkata’; ‘Bangalore’ went back to ‘Bengaluru’; ‘Bombay’ changed to ‘Mumbai’, allegedly because it was a foreign name. But ‘Allahabad’ was not restored to ‘Ilahabas’, or even to ‘Alhabas’. The choice of ‘Prayagraj’ as a new name points to a conspiracy, to a form of retrospective nostalgia for a past that did not include Muslims.

The city was being recast in a monocultural mould. The religious Kumbh fair, held once in twelve years, has always been a large affair drawing hundreds of thousands of visitors. The last ardh-kumbh (a half-cycle fair held every six years) was heavily advertised; over 120 million were expected and a reported 220 million visitors showed up, with great pollution the result.16

There was no concurrent attempt to salvage the university, or to create new cultural landmarks that were inclusive. Instead, places named after Muslim rulers were targeted: a railway junction called ‘Mughal Sarai’ was named for Deen Dayal Upadhayay, a Hindutva ideologue and a divisive figure. Faizabad, the former capital of the province, had its name changed to ‘Ayodhya’, an ancient kingdom associated with Ram, who is worshipped as God and in whose name much violence has been unleashed upon Indian Muslims. ‘Ayodhya’ was already the name of a neighbouring town, which houses the destroyed Babri mosque. Hindutva outfits claim the mosque was built on top of a temple, of which there is no archaeological evidence. There are hundreds of other Ram temples in Ayodhya, but the aim was spelt out in the slogan: ‘Mandir Vahin Banaayenge’, ‘We will build a temple there’. On the same spot where the mosque stands. A decades-long argument in the Supreme Court concluded with the judgement that even though the demolition of the mosque was illegal, a temple should be built in its stead.17

There is no archaeological answer to if and when Lord Ram lived, much less the exact time and location. Everyone understands this, including those who destroyed the mosque. The destruction was erasure, just like with the city names. Further down the same road are veiled threats targeting mosques in other towns like Kashi and Mathura.18

Muslim self-expression has been challenged through direct violence, as in the case of a teenager who was beaten to death in a train for no ostensible reason other than that his cap and his name gave away his social identity,19 and also through the sort of chicanery attempted by a member of Parliament who alleged that mosques were ‘mushrooming on government land’ and submitted a list of fifty-four mosques and graveyards in his West Delhi constituency. The Delhi Minorities Commission visited all fifty-four structures and found none to be illegal. In fact, one of these was a mosque that the MP’s own father, a former chief minister, had helped construct.20

Svetlana Boym has written of conspiracy as ‘an imagined community based on exclusion more than affection’. The unnaming of Allahabad and the false-naming or demonisation of Azamgarh is part of this conspiracy. It seeks to erase our collective memory of Indian Muslim rulers as builders, aesthetes, administrators, and of our home towns being sites of synthesis and confluence. For Indian Muslims, such erasure is an assault upon their inner homeland. It makes them feel unseen, unheard, unremembered. It also erases the memory of the reason so many Muslims were so successful as rulers in India.

Culture is a slippery, fluid thing, but powerful elites like to bolt everyone down in their respective positions – victor, loser, ally, subordinate – by erasing all evidence of fluidity. Racism and slavery operated on similar models, as does the caste system. People have always changed religion to combat hierarchies. In ancient India, they turned to Buddhism and Jainism. In the medieval era, they adopted Islam, Christianity or Sikhism, either to escape caste or to align themselves with the faith of more powerful kings. Part of the work of restorative nostalgia in India is a punitive erasure of these movements.

The word for reconversion to Hinduism is shuddhi, or ‘purification’. Another term is Ghar wapsi, or ‘homecoming’. The words are meant to suggest that Muslims and Christians have strayed from ‘home’ and must be brought back. One way of doing this is to incentivise Hinduism by accepting, at least in theory, that caste-based untouchability is outdated. Another way is to make the country a hostile place for minorities. Demolishing mosques, attacking missionaries, renaming cities are all part of the latter approach. Besides, there are attempts at new laws to forbid religious conversion. Once again, people are being bolted down into their respective social positions.

*

Sangam is one of my favourite words. It isn’t an object or monument. It is an embrace between fluid entities. It is a veneration of flow itself, of mingling without fear of losing yourself. That this was a way of life for millions of people in north India is evident, even now, if you look closely at the map.

This year, driving towards the Sangam, I turned to Google for navigation support. The map unfurled like a hoary djinn speaking for the city of my birth. Around the confluence were scattered a dozen pinpoints of spiritual diversity: Tikarmafi Ashram, Ma Sharda Mandir, Shiv Mandir, Jhusi Dargah Shah Taqiuddin, Mazaar-e-Pak Hazrat Ali Murtaza, Murad Shah Baba Mazaar Shareef.

I took a screenshot as a souvenir, uncertain that these names, or even the physical sites, would survive. Uncertain what else would be lost.

I used to adore Prayag. I had once taken a boat out to the point where the rivers meet and allowed myself to be brow-beaten by a Pandit who hung about insisting that I couldn’t possibly not need his services, so what if I wasn’t quite Hindu? I allowed him to float lamps and flowers in my name, and paid him. None of it felt unnatural.

The spiritual fluidity of India is one of the things that gives me balance. It is natural for most of us to be devoted to our own traditions, but also to be open to other spiritual pathways. Hundreds of millions go to temples and dargahs and churches. They would not immerse themselves wholly in the rituals of the other, but would brush against other sacred norms in the belief that piety was piety, no matter where it came from. I myself visit any sacred place that doesn’t shut me out. It only strengthens what I have.

I revel in the wisdom of symbolic adjustments made by spiritual masters of yore so that many more might feel included. It is common to see images of Mother Mary draped in a saree, or a Sufi dressed in saffron, as the saint of Deva Sharif did. Or it could be a man dressed always in a bright pink kurta and black cap, and smoking cigarettes, who occupied the seat of leadership at a dera, a spiritual residence, devoted to Panj Pir in Amritsar where you’d find images from the Hindu pantheon alongside Machhli Pir, who is also Zinda Pir, or Jhulelal or Khwaja Khizr.

I had once stopped at a tiny roadside shrine in Amritsar, Punjab. It was the tomb of a Muslim Sufi saint, Pir Baba Nupe Shah, and contained objects similar to alams, decorative replicas of the standards carried to the battlefield by Imam Hussain. It also contained pictures of Hindu gods. I put questions to the men who took care of it. They weren’t sure what they were devoted to. All they knew was that it was a holy place. One of the men had a tattoo on his forehead. He got it at a religious fair in Rishikesh. Hindu sadhus had asked him to get a tattoo of a crescent moon instead of an Om, so that he may not lose his connection with the spiritual tradition he came from. The man had a Hindu name. Or perhaps he had adopted one. Who knew? Who cared? He’d found a place and a practice that suited his needs.

It is into this confluence that I was born but, like the rivers Ganga and Yamuna, the mix and flow of our lives is dammed up and polluted to the point of toxicity.

I catch myself wondering these days whether Azamgarh too will cease to exist, as Allahabad and Faizabad have disappeared from the map of my times. Its loss of name would stick in my throat like a fish bone. The loss of Allahabad does stick in my throat.

Perhaps what A. K. Mehrotra had said is true – dust to dust. That’s the story of this place. I look at the riverbank with tired eyes. It is bald of forest cover. Religion is fine. Surely, there could also be gardens, benches, trees, cafés, art installations? But no. Nothing.

Sometimes I think about 1857 and wonder if, when houses are razed, restless spirits are released. Perhaps there are ghost trees, strung with the spirits of six thousand natives. Perhaps ghost carts do the rounds, cutting down rebels hung at crossroads. Perhaps it is a curse. The wealthy always scrambling to buy up their lives. Sacred rivers choked and emaciated.

Gyanranjan wrote that he tried to kill the Allahabad within, because it was impossible to have two lovers: ‘Ultimately, Allahabad took leave of those who had left Allahabad.’ But what happens to those who never left, yet found that the city they knew was gone?

I hear muted sighs, sardonic laughs from lifelong residents. Someone says, the High Court isn’t named for Prayagraj yet. Someone else says, it is rumoured that the High Court itself is leaving town. Someone clings to a shred – the university is still Allahabad – but nobody believes that it will remain. Nobody says, what’s in a name?

I wonder, when I get my passport updated next, should I say that I was born in Prayagraj? Can I swear to it and put my signature on it, that this is the truth to the best of my knowledge?

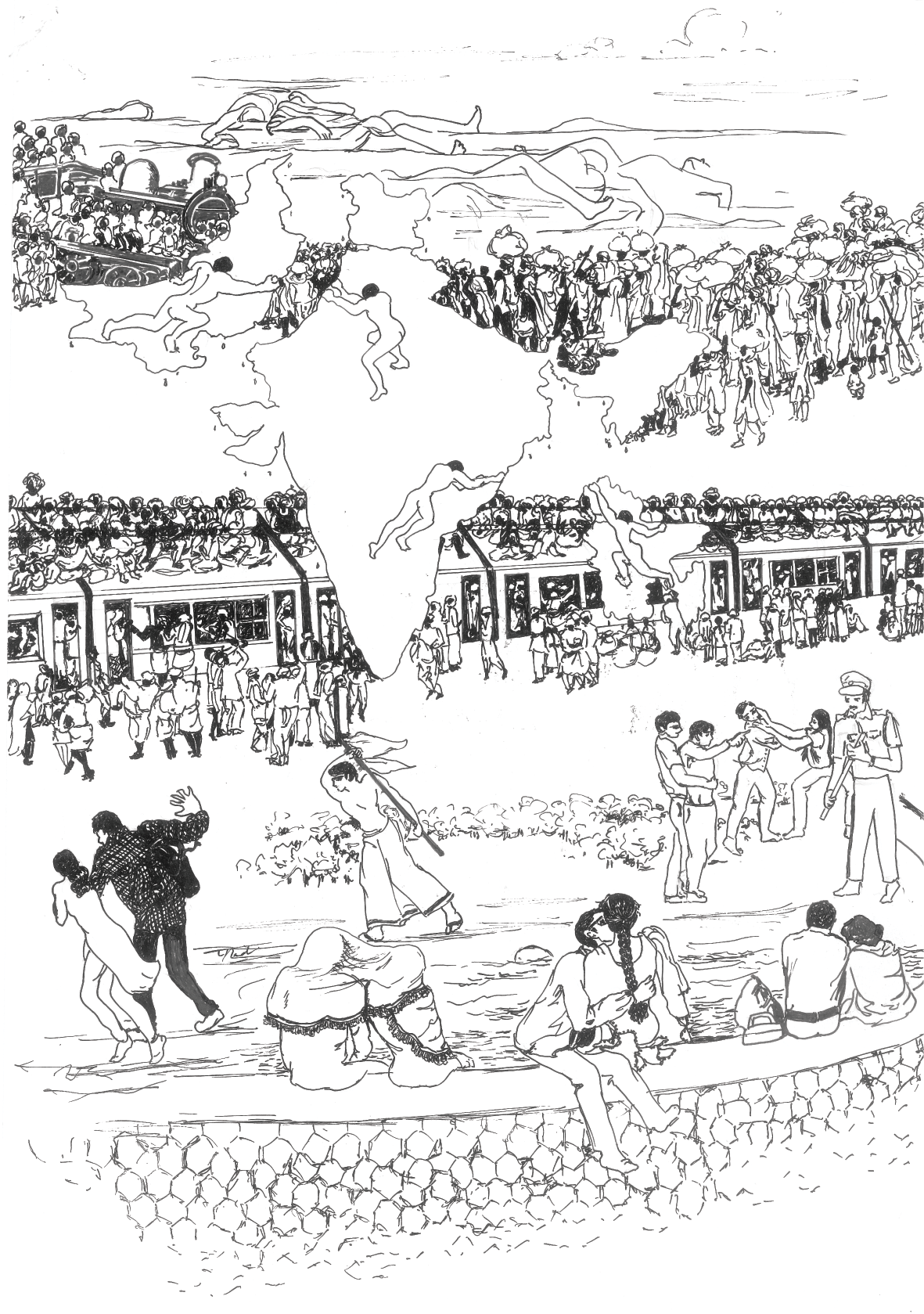

The Partition of India was a horrific event and the aftershocks continue to reverberate across the subcontinent.