Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 July 2023

Summary

The introduction presents an overview of the book’s argument and the theoretical framework that guides the project. It also lays out the contributions the book will make to the historical literature of slave resistance. The argument is that enslaved women resisted slavery with lethal force and when they did so, their own ideas about injustice were a central motivation. A new Black feminist theory is introduced and outlined: the Black feminist practice of justice. The core tenets of this philosophy includes the women prioritizing their perspective and how they defined justice, understanding the stark lack of justice in the judicial system, Black women’s rationality and prior planning, proportionality, a concept of “just deserts,” and their resignation to accept their fates for exercising lethal force.

Keywords

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

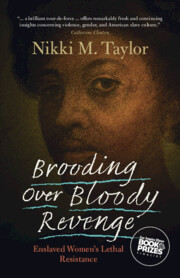

- Brooding over Bloody RevengeEnslaved Women's Lethal Resistance, pp. 1 - 21Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023