1.1 How Was and Is Latin American Legal History Written?

Presenting a legal historiography of Latin America in just a few pages is a challenging task. To begin with, it is necessary to take a position on whether there actually was a geo-cultural entity with that denomination; a collective space that has existed (and continues to do so) under a normative system whose history has been the object of professional narratives. If we were to accept this point of view, we would be back, almost a hundred years later, to cherishing the dream of “the epic of Great America” that was launched in 1932 by the American Historical Association, and of a desirable “general (legal) history of America.”Footnote 1 But we can also opt for the description of a plurality of territorially localized legal histories which more or less coincide with the current sovereign states. Broadly speaking, it is possible to establish the boundary between the comprehensiveness of a legal American Ancien régime and the “national definition” of the law at the time of the processes of independence. However, this approach, while undoubtedly useful, is in practice fraught with difficulties.

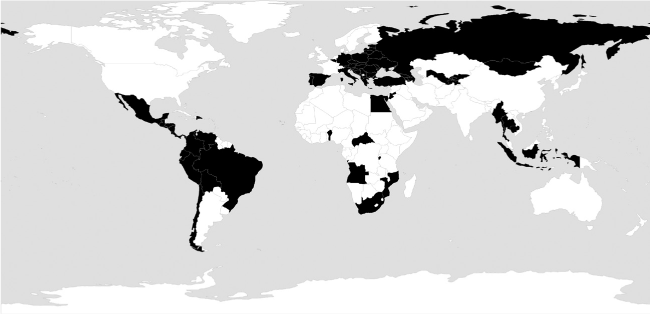

On the one hand, the Latin omits or silences the American, that is, the presence and experiences of indigenous peoples whose history rarely enters the narrative; an issue of capital importance that only began to receive attention at the end of the last century.Footnote 2 On the other hand, the traditional approach – but also the proposals intended to renovate classic historiography – leave non-Iberian America (English, French, and Dutch, but also Russian and Danish, to be precise) out of the picture, although the facts of the past reveal crossed experiences and diverse spaces of influences. This was the case of Franco-Spanish Hispaniola and the Brazilian Nova Holanda as well as the Californian missions and the Russian empire’s claim to territories on the northern Pacific coast. And even within the Peninsular tradition itself, the duplicity between Hispanic America and Portuguese America makes it difficult to articulate a historiographical discourse around the so-called derecho indiano, that great legal experience which, as António Manuel Hespanha has demonstrated, cannot simply be applied to the case of Brazil.Footnote 3

The picture is complicated by the diverging development of local historiographies; the image of the “leopard skin” used by the well-known Americanist Peter Novick is useful in this respect, as it symbolizes the fragmentation of research topics and approaches.Footnote 4 Indeed, the sovereign nations that were born out of the processes of independence have their own traditions (histories of derecho patrio), with a remarkable production of narratives; only a few subjects – as is the case with the codification of private law – have received continental attention.Footnote 5 There are states with a more robust historiographical practice, where legal history has existed for a long time as a subject taught at university; they contribute to common knowledge with textbooks and journals (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico). These journals have generally been founded only recently (ranging from the 1970s in Chile and Argentina to the present day in the case of Brazil). Where there is no academic focus on the field, it is not uncommon to find studies of a nonprofessional nature, that is, research work that is undertaken by jurists and historians who specialize in other areas and occasionally take an interest in the law of the past; their methods and results are, of course, quite different.

Given the earlier-mentioned difficulties, it only seems possible to outline the circumstances in which interest in the historical research of the law(s) of Latin America – including Brazil – emerged, and its subsequent development.Footnote 6

The Origins of Latin American Legal Historiography

The academic study of early (modern) derecho indiano begins in 1883, on the occasion of the celebration of the third centenary of Hugo Grotius’ birth.Footnote 7 Ernest Nys’ contribution on ius belli and the predecessors of the great Dutch humanist and writer preserved for the benefit of modern legal science the so-called magni hispani – until then rarely studied – as a brilliant group of Thomist thinkers who discussed the legitimacy of Castilian rule in the Indies and the conditions for a legitimate war of occupation.Footnote 8 The origins of international law of “Spanish” mold were thus mixed with the study of the Iberian domination of America and the war against the “infidel Indians,” who were supposedly opposed to the ius communicationis imposed by the Castilian and Portuguese adventurers and justified by the theologians of Salamanca or Évora. It was in this context that the historiographical invention of the so-called derecho indiano took place. It consisted of a peculiar system “made up of those legal norms – royal charters, provisions, instructions, ordinances, etc. – that were dictated by the Spanish monarchs or by their delegated authorities to be applied exclusively – in a general or particular way – in the territories of Spanish America.”Footnote 9 The chronological sequence of the works of Eduardo de Hinojosa y Naveros (1852–1919), the scientific father of legal history in Spain (and consequently, in Spanish America), is revealing: His acclaimed study Influencia que tuvieron en el Derecho público de su patria, y singularmente en el Derecho penal, los filósofos y teólogos españoles anteriores a nuestro siglo (1890) was followed by Las Relecciones de Francisco de Vitoria (1903) and Los precursores españoles de Grocio (1911). Since then, the titles to the Indies by conquest, the incorporation of the new territories to the Crown of Castile, the concept of legitimate war, the papal bulls that divided the newly (and yet to be) discovered oceanic and terrestrial regions between Castile and Portugal, the legal status of the new subjects, the evangelizing cause – all these factors have constituted the main arguments of Americanist legal historians.Footnote 10

Meticulous Documentation: The Archivo General de Indias

The study of the theological roots of the “discovery” of America ran parallel to the first undertakings in editing and publishing documentation. The work of the Royal Academy of History (Madrid), the modern chronicler of the Indies, was decisive. Despite its errors and inexplicable omissions, the renowned Colección de documentos inéditos relativos al descubrimiento, conquista y colonización de las posesiones españolas en América y Oceanía (first series forty-two volumes, 1864–1884) provided an enormous mass of unpublished sources, which was completed in the twentieth century by a second series (twenty-five volumes, 1885–1932).

These were documents that, according to the subtitle of the collection, were “drawn from the archives of the kingdom, and especially from the archive of the Indies.” This archive, located in Seville, the old port of the Indies, was and still is the world’s main repository of documents for the history of the law and the governance of Spanish America.Footnote 11 Founded in the time of Carlos III (1785) for the custody and administrative use of the papers of the Council of the Indies, it was belatedly opened to public consultation at the end of the nineteenth century, on the occasion of the fourth centenary of the “discovery” of America (1892) and the Hispanic-Portuguese-American Congresses held at the time (conferences of Americanists, geographical, mercantile, medical sciences, legal studies, military, literary, pedagogical), which represented the first attempt at a “global” study of all things American.Footnote 12 The archive was placed in the hands of experts – professional archivists who were members of a corps of civil servants created in 1858 – and shortly after acquiring the status of “general archive” (1901) under the Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts, the catalogs were made available and historians were offered professional assistance. It is not by chance that among the first historians to consult the archive were Latin American scholars, who came to Seville to document their national histories, but also to clarify the territorial limits of their countries of origin, which were often the subject of disputes. This important historical and legal question was addressed by the Ibero-American Legal Congress of 1892. Indeed, it is no coincidence that the central theme of the meeting, which was discussed from historical and geographical perspectives, was international arbitration.Footnote 13

Spanish Heritage as Hispanidad

The fourth centenary of the “discovery” saw the birth of hispanidad, a hard-to-define concept that soon morphed into a Hispanoamerican holiday.Footnote 14 The royal decree of September 23, 1892 (Gaceta of the twenty-fifth) declared October 12 an official holiday, “without prejudice to the ability for the Crown with the Cortes to declare it perpetual thereafter.” The Spanish government even got Italy – the disputed land of Christopher Columbus – and several transatlantic republics to establish this holiday. However, the celebration of October 12 – the day of the Virgen del Pilar, patron saint of hispanidad –Footnote 15 as a public holiday, endowed with the perpetuity that it lacked at the outset, was born years later at the initiative of Argentina, and announced as Día de la Raza (1917); Catholic militancy, represented by the priest Zacarías de Vizcarra, dominated the celebration.Footnote 16 The well-known historian Richard Konetzke, who was primarily responsible for the promotion of Ibero-Americanist studies in Central Europe, also adhered to the idea of hispanidad.Footnote 17

These circumstances would seem of little relevance if it were not for the fact that they responded to a certain cultural context. I am referring to the reason for the “decline of the Latin race” – the surest proof of which was allegedly the adverse result of the Franco-Prussian (1870) and Hispano-American (1898) wars – in the face of the “Anglo-Saxon race,” which was said to be “younger, more Protestant, richer, and more powerful.” The ideas codified by the Italian sociologist Giuseppe Sergi in his famous work on La decadenza delle nazioni latine (1900) entered the mainstream – the early, multilingual experiment (French, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian) of the newspaper La Raza Latina (1874–1884) is significant – and this heartfelt latinidad, seen from America, seemed to prelude the hispanophile movement that dominated Argentina after the centenary of the May Revolution (1910). Having lost the war of arms, it was now necessary to win the war of language and culture.Footnote 18

It is worth recalling that as late as the fourth centenary of the “discovery,” the Spanish-Portuguese-American Geographical Conference (October 17 to November 4, 1891) was presented as the “congress of the race that discovered and conquered worlds and oceans,” a (white and dominating) race of peoples who “constitute a great family that cannot live disunited without great prejudice to their general and private interests, and that, at a minimum, a commercial coalition is required to guarantee the future of all the states of Spanish and Portuguese origin.” This way, a close ideological relationship linked the concept of hispanidad with the “moral superiority of the Latin race” and with the American adventure of the Iberian peoples: “The social regime that Spain established in its colonies by means of its admirable laws of the Indies is superior to all other systems of colonization, which exploit rather than civilize, and cause the extermination of the indigenous races.”Footnote 19 I know of no better synthesis of the clichés that a large sector of Americanist legal historiography has carried forward to the present day, where the “Hispanic race” (Portuguese and Castilians, and their “Creole” descendants) was clearly opposed to some “indigenous races” that only appeared in the general picture in order to show the ethical-religious, and thus civilizing, stature of Peninsular colonization as opposed to the materialistic and abusive English colonization. The Africans, who were brought to the North and South Americas by way of forced, criminal abduction and enslavement, were not even mentioned.

History Writing and Republican Culture: Brazil

The bases that inspired Hispanic racial ideology and the resulting legitimizing narrative developed differently in Brazil. A few years after the reform that introduced the study of the history of law as a subject taught at university in Spain (1883), and long before the appearance of José Caeiro da Matta’s História do Direito Português (1911), the minister and patriot Benjamin Constant Botelho de Magalhães introduced legal history at the University of Recife in Pernambuco (1891). There, the holder of the chair, the young publicist José Izidoro Martins Junior (1860–1904), who was a disciple of Tobias Barreto and an abolitionist, published História do Direito Nacional (1895). A pioneer of its kind, this scientific-positivist work (Martins confessedly belonged to the “naturalistic school”) conceived law as “an organic whole determined by bio-sociological fatalities,” and therefore with no prior commitments to morality or the attribution of a transcendent origin to the legal experience, which was perfectly in line with republican secularism.Footnote 20 Nothing of the kind existed in the Spanish language, neither for derecho indiano nor for derecho patrio. When it finally arrived – I have the prolific Argentinean author Ricardo Levene (1885–1958) in mind – the theoretical foundations, and consequently the subject matter addressed, responded to partially different parameters.Footnote 21

In his treatment of the legal past, Martins followed the filiação method (whereby the present was only understandable on the basis of the past), which led him to deal, in part one of his História, first with the history of Portuguese law (Epocha dos antecedentes) before moving on to trace the institutional history of Brazil. In doing so, he inaugurated a practice that was followed by future Latin American legal history textbooks. The past was described according to its “genetic” elements, with Portuguese (Alexandre Herculano, Teófilo Braga) and Brazilian (Cândido Mendes) classics serving as the plinth on which then, in part two, the “national” legal experience was based (Epocha embryogénica). This was supported by motives and authorities imbued with the same positivist ideal of Comtian and Spencerian tradition (especially Italians: Brugi, Cogliolo, D’Aguanno). As such, Martins’ História offered a diverse view of the colonial past.

To begin with, the so-called “ethnic-legal protoplasm” of the country was racially mixed (“the Brazilian people is currently made up of Aryan whites, Guarani Indians, blacks of the Bantu group, and mestiços of these three races,” in the words of the writer Silvio Romero). After asserting the superiority of the white Portuguese, the discoverers, and conquerors (the raça predominante or “predominant race”), Martins resorted to another quotation, this time from Carlos Frederico von Martius, to warn against the error of forgetting “the forces of indigenous and imported black peoples” – a fundamental aspect, alongside the European racial substratum, for the formation of Brazilian nationality.Footnote 22 This was, in short, quite the opposite of the exclusionary hispanidad that was making inroads in other American lands.

Thus, the starting point for a rendition of Brazil’s legal past was this racial diversity, which was reconstructed thanks to an extensive library produced by ethnographers and philologists who identified the origins, differences, and settlements of the indigenous and African populations. However, according to this version, the African populations – the authority in this case was another professor from Recife, the great Clóvis Beviláqua – did not really contribute anything to Brazilian law because of their condition as enslaved people (“without personality, without legal attributes beyond those that can emanate from a bundle of goods”). This was just the opposite of the indigenous peoples, whose customs and institutions – Beviláqua had researched those too – Martins treated with some attention. But it was clear that, both in the colonial past and in the present system, the contribution of Portugal, “a nation already in existence, which has a complete and codified legislation,”Footnote 23 had been decisive. It remained for the republican government to develop a program of “nationalization” that would succeed in synthesizing the three racial elements that made up Brazil in order to obtain “a homogeneous and compact whole, corresponding worthily to the physical and social environment in which it has to act and evolve.”Footnote 24 In this way, Brazilian legal historiography put itself at the service of the nation whose racial complexity was sublimated into a happy tropical “melanism.” Compared to other cases – the United States, in particular – it was argued that “in no country in the world do the representatives of such different races coexist in such harmony and under such a profound spirit of equality.”Footnote 25

The Development of Literature on Derecho Indiano

The important role played by Argentina in the celebration of the raza – the apotheosis of a Euro-Creole super-nation – and its commitment to legal historiography through the figure of Ricardo Levene, who succeeded Carlos Octavio Bunge in the chair of “Introduction to Law” at the University of Buenos Aires, can be justified by recalling the American journey of Rafael Altamira y Crevea (1866–1951), a friend and correspondent of Levene.Footnote 26 Altamira, who stood out among the first Spanish professors of legal history, took up the chair at Oviedo in 1897 and then went on to become the protagonist of a famous cultural embassy to Latin America, where he gave seminal lectures (1909) – particularly influential and prolonged in the case of Argentina.Footnote 27 This allowed his country to strengthen ties with its former colonies and to develop a perspective for the future after the loss of the last Spanish overseas territories. Similarly to Levene in America, Altamira founded American legal historiography in Europe. His experience as a researcher of customs (including indigenous customs, 1946–1948), his skepticism toward legislation as a primary source of law, and his attention to popular legal conscience – all traits of the Krauso-positivist tradition of thought in which Altamira had been trained – coincided with the professional vision of Levene, a jurist-historian and “sociologist” concerned with the reality of law and the pluralism of normative manifestations.Footnote 28

Altamira’s move from the small town of Oviedo to the Central University (Madrid), where he held the chair of “History of the Political and Civil Institutions of America” from 1914 to 1936, enabled him to exert a considerable influence on the younger generation; thus, the first corpus of scientific studies on derecho indiano formed around him. The research focused more on the recovery and history of legal sources than on the reconstruction of the historical regime of American institutions.Footnote 29 Altamira added his own work to the magisterium, especially his late contributions. These were published when the elder Altamira, who had been a judge at the International Court of Justice (1921), went into exile in Mexico (1944–1951) following the terrible Spanish civil war.Footnote 30

Two main developments can be traced back to Altamira. On the one hand, mention should be made of the figure and work of his first disciple, the Valencian José María Ots y Capdequí (1893–1975). A professor at the faculty of law, his tenure for several years at the University of Seville (as of 1924) allowed him to develop his research and participate in the many initiatives that arose on occasion of the great Ibero-American Exhibition (Seville, 1929). In addition to monographic studies, especially on questions of private law,Footnote 31 during his exile in Colombia, the republican Ots produced the first and most complete general exposition by a Spanish author: The Manual de historia del derecho español en las Indias y del derecho propiamente indiano (1943). Published in Argentina with a prologue by Levene, it served as a reference book for the teachings which, little by little, began to consolidate in several American countries. Other younger researchers belonged to the same school as Ots, such as Javier Malagón (1911–1990), a jurist and historian who was forced to leave Spain after the war but went on to have an excellent career in Santo Domingo, Mexico, and the United States, and Juan Manzano (1911–2004), professor of legal history in Seville and Madrid, scholar of American legal sources, and well-known supporter of the theory according to which America was discovered well before Columbus “discovered” it.

On the other hand, the American followers of Altamira – beneficiaries of the boom in historical studies brought about by the Spanish Republic – created local schools of varying dimensions.Footnote 32 Besides the Chilean Aníbal Bascuñán Valdés (1905–1988), Alamiro de Ávila’s teacher and an expert in legal history and public law,Footnote 33 the Mexican Silvio Zavala (1909–2014) stood out above all others. He became the reference of a school that has enjoyed, along with the Argentine school, the greatest presence in historiography. A contemporary of Zavala’s who also received extensive training in Europe and North America was the Peruvian Jorge Basadre Grohmann (1903–1980). He was among the first to publish a work of general ambition that, once more, led from pre-Hispanic antecedents to Peruvian law (Historia del derecho peruano, 1937). From a theoretical point of view, having learned the lesson from Altamira, Latin American historiography in the 1930s and 1940s sought to establish in its studies a supposedly objective – one might say “Rankean” – truth through a very meticulous use of sources and the orderly presentation of data that was always compared and contrasted. This approach nevertheless failed, for lack of direct testimonies, when attempts were made to reconstruct institutional life prior to the conquest.Footnote 34

The relationship of Latin American researchers with the legal past of the colonizing powers, particularly Spain, was variable and conflicted. It was closer in the cases of Chile and Argentina, and less intense in countries which, like Mexico and Peru, had highly developed indigenous presence.Footnote 35 Surely the most radical proposal came from the highly respected Alamiro de Ávila, who did not hesitate to affirm that Chileans “are Spanish and our origins are the same as those of any Spanish people,” while the indigenous peoples and their experiences were, at most, “one of the elements, and in our case, not an important one, that inform derecho indiano.” Consistent with such an extreme form of Eurocentrism, the reform of studies promoted by Ávila at the University of Chile (1977) allowed him to teach two courses in legal history: the first focused entirely on the history of Spanish law, from prehistory to the independence of American regions; the second, on derecho indiano and Chilean derecho patrio.Footnote 36 Latin American legal history textbooks typically began with a chapter addressing Spanish legal history in more or less detail – as Levene had written, “the history of America begins with the history of Spain” – but Ávila went so far as to reduce Chile’s legal history to Spain’s. I know of no other similar case.Footnote 37

Zavala’s example in Mexico did not immediately generate a legal historiography worthy of the name. In fact, the formalistic description of the great legal monuments, such as the Siete Partidas or the laws of Hispanic America (Recopilación de leyes de Indias, 1680), served to express a fundamental conception that accepted the inexorable rise of the state as a political form and the “civilizing logic” of the law as the only legal source, in a superficial and uncritical account. The renewal of studies only came in the 1970s, when Guillermo Floris Margadant (1924–2002) at the Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas (National Autonomous University of Mexico, UNAM) and the Colegios of Mexico and Michoacán began promoting research work and exchanges and hosting international meetings in the field. The culture that places legal positivism at the heart of legal history has been eroded by the opening up to other historiographical traditions, not only European; it is considered at present a decisive moment in the rebirth of Mexican legal history.Footnote 38

National Celebration and Legal Historiography in Brazil

After Martins Junior’s efforts in Recife at the end of the nineteenth century, no scholars of a standing equivalent to Levene or Zavala emerged in Brazil in the first half of the twentieth century. Nor was there someone like Altamira to strengthen friendships and cultural relations, which were rather better between Portugal and Brazil to start with than those between Spain and Mexico or Argentina. It was not until the 1950s that another account of the História do Direito Brasileiro (I–IV, 1951–1956) was published, thanks to the influential lawyer, politician, and prolific writer Waldemar M. Ferreira (1885–1964).Footnote 39 The sixty years that separated Martins from Ferreira did not, however, consign the history of law to oblivion. Rather, the celebration of another event – the centenary of Brazil’s independence (1822–1922) – gave impetus to historical studies, including legal studies.

In 1922, the first Congresso Internacional de História da América (Rio de Janeiro, September 8–15, 1922) was held, with Ricardo Levene being among the most prominent participants. It was convened by the Instituto Histórico e Geográfico, a venerable institution officially founded in 1838 to seek knowledge of the physical environment – the delimitation of the territory of the Brazilian states was, even with the establishment of the federal republic, merely approximate – and to write the history of the nation. “Among the interconnections of civic catechism,” observed one of its members in 1912, “the study of the home country’s history stands out.”Footnote 40 In this historical meeting, methodologically guided by the positivist historiography of the Third French Republic (Charles Victor Langlois, Charles Seignobos), two subsections dealt with institutional history, another with constitutional and administrative history, and finally, the fifth section treated parliamentary history.

The thematic structure of the congresso was also followed in the second initiative sponsored by the Instituto Histórico e Geográfico.Footnote 41 I am referring to the Diccionário Histórico, Geográphico e Ethnográphico (1922), whose first volume, with general studies on Brazil, also contained chapters of legal interest: besides the usual constitutional (“Organização política,” Max Fleiuss and Augusto Tavares de Lyra) and administrative histories (Max Fleiuss), a “História judiciaria do Brasil” (Aurelino Leal) was added, as well as a descriptive essay on “legal teaching” (Elpidio de Figueiredo). All of these authors were prominent political figures close to the Instituto. For the history of law, the contributions of Fleiuss (1868–1943), permanent secretary of the institute, and Leal (1877–1924), author of a História constitucional do Brasil (1914), stand out above all others. Both produced excellent descriptions, with bibliographical references and extensive notes, of the institutions of government and justice from the early days of the Portuguese presence in America up to the First Brazilian Republic. Their work was similar in chronology, development, and index to the legal-historical texts that were beginning to be published in Spanish-speaking countries.

The Instituto Internacional de Historia de Derecho Indiano (1966)

The academic traditions of research described in the beginning of Section 1.1 and the underlying motives that sustained them – hispanidad, race, religion, and universal destiny – led to the foundation, in the mid-1960s, of the “International Institute for the History of Derecho Indiano.” Gathered in Buenos Aires on the occasion of the Fourth International Congress on the History of America, Alamiro de Ávila Martel (1918–1990), Ricardo Zorraquín Becú (1911–2000) and Alfonso García-Gallo (1911–1992) agreed to promote knowledge of the Latin American legal past by holding regular congresses and publishing their scientific results. This rather domestic foundational meeting in 1966 was followed by another in Santiago de Chile in 1969; since then, an uninterrupted series of conferences has taken place, which now extends to the twenty-first session (Buenos Aires, 2024). Modern historians from other traditions, such as the German (Horst Pietschmann, Enrique Otte), French (Annick Lempérière, François-Xavier Guerra), and Italian (Antonio Annino, Luigi Nuzzo, Aldo Andrea Cassi) ones, further contributed to the efforts of the institute and occasionally participated in its congresses.Footnote 42

We already know that the Chilean Ávila was a disciple of Bascuñán. Zorraquín, like the younger José María Mariluz (1921–2018), was a disciple of Levene. García-Gallo trained in Madrid with Galo Sánchez, a medievalist expert who produced little though important work and always remained oblivious to the history of America. However, Galo Sánchez did open the Anuario de Historia del Derecho Español, which he had helped found in 1924, to research on Latin American law with the help of his friend and colleague Ots Capdequí.Footnote 43 Although García-Gallo devoted his doctoral thesis to the Spanish “theologians-internationalists,” his early research faithfully followed Sánchez’ work on medieval sources.Footnote 44 His dedication to American studies came later, when he assumed the Madrid chair of “History of the Political and Civil Institutions of America” (1944), which had previously been held by Altamira. A monograph on the territorial government of the Indies, composed on that occasion, was the beginning of the very fertile Americanist production of this author.Footnote 45

The 1966 Buenos Aires meeting was inaugural, not only because it initiated a long series of academic encounters, but because this conference laid the foundations that conditioned subsequent research. Alfonso García-Gallo was in charge of providing the methodological guidelines.Footnote 46

The method, in this case, was hardly distinguishable from the techniques that were applied for analyzing historical sources. Since his accession to the chair of “History of Spanish Law” in 1934, García-Gallo had been rejecting any “sociological” temptation in historical-legal studies: the subject “must deal,” he wrote at the time, “exclusively with legal matters and deal with all legal questions.” A fundamental distinction supported his approach: whereas historical science deals with singular and unrepeatable facts, the legal fact, born of a preexisting mandate (of a norm), was destined to repeat itself as long as the rules that constrained it did not undergo changes. That was the reason why the history of law was a branch of legal science that had to be pursued “purified” of cultural, economic, or socio-political circumstances.Footnote 47 He further argued that “derecho indiano – like all law – is an ordering of social life; but in no case is it social life itself, nor can it be confused with it.”Footnote 48

The commitment to “juridicality,” in the sense of an exclusively legal approach to research that did not take into account sociological or economic considerations, involved the rejection of the preceding tradition, in particular, that represented by Rafael Altamira. For García-Gallo, this author lacked “personal research,” although he valued his role in guiding numerous disciples; and now – he wrote in 1953 – “sociological concern has begun to give way to an essentially juridical consideration of the history of derecho indiano.” If this went beyond Altamira’s “historicist” approach,Footnote 49 it also went beyond Levene: the admired Argentinean master “in his sociological orientation of legal history … remains in the traditional line of his predecessors.”Footnote 50

A subsequent study, born out of the Buenos Aires meeting and presented at the second conference (Santiago de Chile, 1969), codified the same method, that is, working techniques and presentation of results. This is the Metodología de la historia del Derecho Indiano (1970), disseminated as the vade mecum of the discipline.Footnote 51 It does not take much effort to identify the lines of thought to which the work responded. The past was assumed as something given, which the researcher had to recover through intense study of the sources, without falling prey to subjectivity: “the personality of the scholar must yield to it.”Footnote 52 The Metodología conceived law as an autonomous object, susceptible of separate study: “It undoubtedly constitutes an aspect of the global culture of society, but with sufficient entity to be an object of study in its own right.” To this end, García-Gallo proposed to follow the “institutional orientation”: only the purely normative aspects of basic social relations were of interest to the legal historian. In reality, the pure and objective “noble dream” of the jurist-historian was in the service of a goal set fifteen years earlier: “to awaken or revive in all parts of America the interest in derecho indiano” and to demonstrate scientifically that it “was a decisive element in the forging of the peoples of America, in whom it inoculated the ideals of justice and liberty, who it led – by way of law – to achieve their independence; and because this Indian Law, given that it was common to all Spanish-speaking peoples, together with the language, constitutes the substratum of their cultural community.”Footnote 53 The fin-de-siècle paradigm of Euro-Creole and Catholic hispanidad was still present.

New Horizons: The Casuismo of Víctor Tau

The rigid separation between the history of derecho indiano and the history of the national laws of Latin America guided the work of the Instituto Internacional and its conferences, although the methods used for the former did not differ much – the influence of García-Gallo on Latin American legal historiography was and is considerable –Footnote 54 from those followed to develop the latter. Changes in themes and approaches only began on the occasion of the eleventh conference in Buenos Aires (1995), thanks to Víctor Tau Azoátegui (1933–2022), a well-known Argentinean legal historian, who was a disciple of Levene and an admirer of Altamira. Tau’s long trajectory as an active member of the Instituto Internacional revealed, indeed, an original path: he had been interested in customs (third conference, Madrid, 1972; fourth conference, Mexico, 1975; seventh conference, Buenos Aires, 1983), low-ranking norms dictated by lower authorities (sixth conference, Valladolid, 1980), and local objections to the legal orders (fifth conference, Quito-Guayaquil, 1978).Footnote 55 His sensitivity to what were, until then, considered minor regulations was well demonstrated. At the eleventh conference (1995), his paper was developed and published separately, and Nuevos horizontes en el estudio histórico del derecho indiano (1997) offered a new canon for the historical-legal studies of Latin America.

The paper was not the result of chance. Three years earlier, Víctor Tau had published Casuismo y sistema, an original treatise whose general theme made it resemble a manual. A basic thesis, however, distanced it from the usual description of sources and institutions: that there was tension between a case-based culture (casuismo) and systematic efforts, which for this author contained all the experience of the early modern colonial law.Footnote 56 Ortega y Gasset’s distinction between beliefs and ideas served Tau to articulate his work: the belief in casuismo coexisted with the idea of system, as followed in four fields of analysis (namely, the jurist’s apprenticeship, the creation of the law, the jurisprudential works, and the application of the rules). In fact, the culture of derecho indiano was always a culture of the case, although it was familiar with ideas of system which were nevertheless extrinsic to the legal object they pretended to organize in a rational manner, and therefore never altered the dominant conception. The final result could not have been more “impure,” since the reactivation of “a way of thinking about law” – the dominant case-based approach – which the rationality and abstraction of modern legal conception had condemned to oblivion only seemed possible by framing the legal fact within morality, theology, and politics: “The notion of a closed and sufficient legal order, conceptualized and methodically set out in laws is inapplicable to colonial law.”Footnote 57 In that operation, the old objective dream that García-Gallo had cherished also disappeared, because “the historian, whose ineludible task is to look at the past, does so from his vantage point, located in the present, where one more turn of history can be glimpsed.”Footnote 58

A general revision of the old ways of practicing the history of law soon followed. Regarding legal sources, Nuevos horizontes denied the leading role of the law in the face of other norms that concurred with it, but also because it was conceived as just another piece of legal culture. From the point of view of the subject matter, a new catalog of arguments – the public servants and the works of theoretical and practical jurisprudence – was offered for future research.Footnote 59 But Tau also challenged the temporal barriers established between colonial law and national law by drawing attention to institutional continuity. Subsequent conferences reveal the impact of these proposals, as the study of the nineteenth century has been commonplace since the Toledo conference (the twelfth, in 1998), and in La Rábida (the twentieth conference, 2019) the theme was Pervivencias del Derecho Indiano en el siglo XIX. In Berlin (nineteenth conference, 2016), “colonial law in the nineteenth century” was directly addressed.

Broadening Horizons

The eleventh conference held in Buenos Aires introduced a novelty: it included Brazilian historians in the list of “indianistas.” Arno and María José Wehling (Rio de Janeiro) contributed a study on the Tribunal da Relação in Rio de Janeiro, and their names have since become a regular presence at the meetings. In those years, Arno Wehling, former president of the Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, later a member of the Academia Brasileira das Letras (2017), participated in the foundation (2002) of the Instituto Brasileiro de História do Direito. Its conferences, the latest of which was held in Curitiba (eleventh conference, 2019), bring together Brazilian, American, and European scholars of the subject, and its Anais – the annals – constitute a rich body of research by the younger ones.

The Wehlings’ approach to Spanish-speaking Latin American legal historiography did not, however, include the communication of methods. A history of the institutions of colonial Brazil was legitimate and possible – few authors promoted it as the Wehlings did – without participating in the scheme of understanding provided by derecho indiano. The analysis of this point fell to António Manuel Hespanha, who was responsible for the inaugural lecture at the Berlin conference.

Spanish nationalism and Portugal’s civilizing mission were the starting points of the historiographies described there. Portuguese historians have thought of the colonial adventure as an experience that was open to local contexts and the plurality of legal and institutional models; the old discussions on Lusitanian racial origins (Oliveira Martins, Sardinha) marked a vision that prioritized the gentleness and friendly character of the Atlantic nation, a romantic and traveling nation due to its geographical conditions. In contrast, drawing on the idea of hispanidad – also Catholic and altruistic – scholars of the Spanish expansion in America emphasized its integrating and unitarian character, as revealed, significantly, by the well-known extension of Castilian law to the new territories and their peoples (“the Indies were not colonies”); certainly, exotic circumstances and normative interventions by peripheral authorities provided specific responses to local problems, but these responses were always integrated into the dominant legal system.Footnote 60 Despite the constant testimony of diversity and casuismo, Spanish-American law was ultimately described as centralist, unitary, and coherent.

Hespanha’s lecture concluded that the two Iberian forms of colonialism responded to an identical religious, political, and legal matrix. As such, the duplicity of historiographical traditions did not respond to appreciable differences in the historical materials. Rather, it was the respective cultural traditions of the nations – the feeling of opposition to Castile in the Portuguese case, and the exaltation of the imperial idea in the Spanish case – that allowed different visions to be developed.

Toward a Postcolonial Legal Historiography

The drawback of all this is that Latin America is presented to us as a gigantic insula in mari nata, empty and available for occupation by the first discoverer; “some interpretative coordinates,” Luigi Nuzzo has rightly written, “from which it was possible to imagine a derecho indiano without Indians and without Indies, a legal history of the conquest without conquest and without conquered.”Footnote 61 This warning finally brings us to the current moment in the historiography of law in Latin America. And here, the work of Bartolomé Clavero stands out in particular.Footnote 62

The connection between “history” and “constitution” has been a constant theme in Clavero’s research. Since his first reflections in Derecho indígena, this author has endeavored to provide an analysis in which the indigenous is the protagonist element. It is understood, in the classical manner, as a status – a specific social condition that locates its members at the heart of the unequal and hierarchical society of the Ancien régime – which is not merely limited to the category of the miserable or the rustic that is more frequently used by historiography. That status was the state of ethnicity, “legally the space that the colonizers reserved for the colonized.”Footnote 63 This is undoubtedly another perspective on the term “race,” which we know to be decisive in the origins and development of Latin American legal historiography.

According to Clavero, ethnicity is accompanied by another concept, the mere enunciation of which is a condemnation, and a general censure of a complacent history. The European presence in America has been a colossal genocide, committed (and partially denounced) yesterday and today, in a “now” that is only too inclined to enact a “white legend,” replicating the leyenda negra or “black legend” invoked by mainly Protestant authors to denounce the atrocities committed by the Spanish in America.Footnote 64 This author’s perspective is one of accusation. “How can we approach colonial history without taking into account the rights of the indigenous peoples who suffered colonialism and suffer its consequences?” is the question – as well as the reproach – launched by Clavero when analyzing António Manuel Hespanha’s contributions to a “direito luso-brasileiro” that could result in a tropical reinvention of derecho indiano.Footnote 65 The question is full of disturbing implications since, in the first place, it draws attention to the omission in the historiographical narrative of the voice of the colonized, whereas philology’s recent contributions now allow us to access a body of sources that enable us to hear it. Clavero’s use of indigenous languages, at least to title his studies, undoubtedly responds to this new sensitivity.Footnote 66 Secondly, and more importantly, historiographical criticism is aimed at unraveling the current effects – as visible in the constitutional and international sphere – of colonial domination, with such relevant examples as modern slavery.Footnote 67 The constitutional history of Latin America – and not only Latin America’s – started from the implicit understanding and dissimulation of ethnicity to configure a deceitful citizenship; it is enough to recall the example of the Mexican state of Sonora y Sinaloa in the times of the 1824 Federal Constitution – since the state charter (1825) suspended the rights of citizens “for being in the habit of walking shamefully naked.” Anthropological diversity sustained the fiction of the public law of independence, prolonging the dictates of the old derecho indiano. It should be pointed out that Clavero’s suggestions have been passed on to recent Brazilian legal historiography, interested in povos indígenas whose rights, yesterday and today, are in continuous dispute.Footnote 68

The history of Latin American law is one, if not the main form, of producing and applying law in Latin America. Or put differently, it is a “history of [Latin American] law in the present.”Footnote 69 It is thus a delicate object that – negatively – invents traditions, forgets subjects, and offers culturally connoted frameworks of understanding. It also – positively – identifies peoples and pluri-national states; it defends jurisdictions, territories, and resources. Scholarly activity ultimately becomes civic engagement. It is no coincidence that this historiographical renewal coincides with a new international law attentive to indigenous peoples and with a renewed constitutionalism.Footnote 70

. . .

1.2 What Is Legal History and How Does It Relate to Other Histories?

Historians, jurists, and legal historians have long debated what legal history is, how it should be done, and what it must accomplish. These debates began long ago and continue to this day. They obscure not only important questions related to what history and law are, respectively, but also what is the point in engaging in legal history at all. Is legal history useful for jurists? What about for historians or the public at large? Moreover, what makes a history legal? Is it the research object being pursued, the sources used, the methodology employed? Or is it more about the questions asked?

In what follows, I deliberately take issue with how legal historians of Latin America, Spain, and Portugal answered some of these questions. I am conscious of the fact that many other scholars have debated them and that these debates greatly contributed to the emergence of the views held by the Latin American, Spanish, and Portuguese scholars whose work I study and that informs my perspective. I pursue this endeavor convinced that the scholarship I examine is insufficiently known to a wider readership, while at the same time, it has and continues to shape the way the legal history of Latin American law has developed. This analysis focuses on what transpired since the 1960s because, although older visions persist, this volume attempts to follow the lessons we have learned up to this point. In part, I do so also as a tribute to António Manuel Hespanha, whose work inspired so many of us, and who was one of the editors of this project but regretfully passed away before we could bring it to fruition. As I wrote this text, I constantly dialogued with his work as well as repeatedly asked myself: What would he have said? How would he have addressed these questions?

The relations between law and history are quite old. It is often argued that, although the realization that laws change over time reaches back to antiquity, the first inquiry that resembles present-day historical epistemology was popularized by legal humanists who in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries set out to criticize contemporary jurists for their understanding and use of Roman law.Footnote 71 Disputing the operative premise that Roman law could serve as a matrix for a universal and atemporal science of law, legal humanists suggested instead that Roman law was a relic of the past. To study it properly, it would be necessary to develop philological and historical methods aimed at reconstructing the original texts while also devising ways to restore their original meaning. Among the methods legal humanists proposed was considering non-legal sources and even artifacts, studying the evolution of language, as well as imagining how readers and practitioners of that time might have comprehended things. Convinced that law was the product of society and therefore must be studied in both its temporal and geographical contexts, legal humanists also turned to observe the local customary law, which they argued was the true law of their communities. Thereafter, and using legal history both as a guide and weapon, legal humanists described Europe not only as a space for a ius commune but also as a patchwork of local legal solutions dependent on the time, place, and speakers involved. They envisioned a peaceful coexistence between a universal science of law and a plethora of specific arrangements that were constantly elaborated, changed, or abandoned by multiple individuals, groups, and communities who sought to define the rules that should guide their interactions.

In their quest to study law properly, fifteenth- and sixteenth-century legal humanists thus contributed to the development of historical methods. Yet, relations between law and history are not only the outcome of scholarly pursuits; they are also embedded in the very nature of juridical practice. More often than not, this practice centers on understanding the legal consequences of something that had already transpired. Evaluating the juridical meaning of both existing norms and past events necessarily involves a certain historical reconstruction, yet jurists and judges who seek to establish how to read certain texts, or how to appraise certain actions, do so in ways both similar and dissimilar to historians.Footnote 72 While the similarities are quite clear – attention to words, detail, context, and circumstances – so too are the differences. Jurists and judges have a practical reason to engage in evaluating historical evidence, namely, the need to solve conflicts. It is legitimate for them, indeed frequently even required, that they ignore all that is not essential to attaining that end. What they seek to uncover is mostly a “usable past,” which can serve as a resource in the present. To draw conclusions, jurists often selectively piece together, reorganize, and reconfigure disparate events that a priori are not necessarily related to one another or are connected in ways other than what they postulate. In other words, their reconstructions are not necessarily intended to uncover the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, but instead to achieve a certain goal. Jurists also inhabit an adversarial culture. There, it is completely normal to claim authority over certain interpretations, arguing that they and only they are correct. This same attitude is applied to their observations of the past, ascribing certainty and singularity where none existed. While historians of course also make decisions about what to include and what to ignore, or how to read what they uncover, their aim is not the attainment of a specific result but the expansion of knowledge. The conclusions and findings of their analyses normally follow the same epistemic rationale: They are not considered definitive, but instead open to rexamination, discussion, and change.Footnote 73 Most historians admit the possibility of a multiplicity of responses, and they are not particularly alarmed by ambiguity, by questions that cannot be answered, or that the past may not tell us all that we need in the present.

Jurists of course also intervene in history by writing it through pleading in the courts or delivering judicial decisions. A judge that orders the correction of a report elaborated by a truth commission, for example, deleting the name of an individual who is listed as having committed human rights violations, interferes with what is knowable and what is considered to have been proven.Footnote 74 Judges also intervene in the production of history when they sit in commissions or trials in which they adjudicate conflicts and determine what had transpired. In all these cases, the proceedings they conduct not only supply evidence that historians can use but also rulings that often illuminate – even determine, in the eyes of many – what the past contained. Juridical reconstruction of history can also be implicit, for example, when judges take “judicial notice” of allegations that involve assumptions about the past or that interpret the past in certain ways that are said to be consensual.Footnote 75 Though supposedly encapsulating common knowledge, controversies among judges, for example, regarding the history of discrimination, the meaning of family over time, or the legacies of WWII, demonstrate that such assumptions and interpretations are not uncontentious.

Expressed in different terms, behind all judicial decisions lies a narrative – implicit or explicit – on how things came to be as well as which lessons have the power to influence our vision of the past and can, therefore, be mobilized to support present-day agendas.Footnote 76 The writing of history by jurists and judges is particularly daunting because they are often ill-equipped to evaluate historical events, yet their rulings provide these events with a definitive narrative that can potentially acquire a normative value.Footnote 77

Despite the enormous differences between historical and legal pursuits, many early historians were jurists, and they employed the techniques of exegesis, discovery, and reconstruction they acquired by studying and practicing law. Though this holds true in many different places, it is particularly illustrative of how scholarly engagement with Spanish American history has developed. In Spain, for example, many consider Eduardo Hinojosa y Naveros (1852–1919) to be the founder of historical studies. Hinojosa also trained many of those who would later go on to become historians of Spanish America. Nevertheless, Hinojosa was a jurist whose work was not particularly focused on legal questions.Footnote 78 Along similar lines, the first university chairs dedicated to the history of the Americas were established in the early twentieth century. These chairs were either situated in law faculties or their holders, among them Antonio Ballesteros Beretta, Rafael Altamira y Crevea, and José María Ots Capdequi, taught both history and law.Footnote 79 These intellectuals were also responsible for expanding the legal history of Spain (Historia del derecho español) to include colonial law – a law that eventually came to be identified as derecho indiano (see Section 1.1).

Developments in early twentieth-century Spanish America were not very distinct. The Argentinean Ricardo Levene, for example, held the chair of history before switching to legal history; the Mexican Silvio Zavala, who studied law, spent most of his career among historians; and the Brazilian Salomão de Vasconcellos, who trained as a lawyer but went on to become a prominent historian. This generation of foundational scholars, all trained in law, did not distinguish between history and legal history. Regardless of whether they were working in law faculties, history departments, studied history, or studied law, they used similar sources and pursued similar objectives to such an extent that it is often difficult to ascertain their formal education and field to which they belonged.Footnote 80

Later generations did not continue pursuing this initial convergence of disciplines. Legal historians writing on this parting of ways usually blamed historians for having abandoned the law in favor of social and economic history, which, whether under the spell of the Annales school or Marxism, portrayed law as a stale and irrelevant pursuit. Historians, they argued, moved away from legal and political history, adopted quantitative methods, and embraced longer temporal periods, moves that together often resulted in the removal of law from their list of research interests. Even if this analysis rings true, it is equally clear that legal historians have also contributed to this estrangement by abandoning history and by producing studies that mainly sought to reconstruct the genealogy of rules and institutions, a genealogy that was generally portrayed as the progressive betterment that led to present-day structures.Footnote 81 Conceiving of law in terms of an autonomous field, law faculties in Latin America, Spain, and Portugal monopolized legal history, and its practitioners were mainly interested in what some have identified as an “internal” history that looked at the law as if it had no “external” history, for example, its relationship to society.

Reacting to this growing separation, from the late 1960s onwards, many Latin American, Spanish, and Portuguese legal historians expressed their commitment to another type of legal history that also doubled as social, institutional, and political history.Footnote 82 To do so, proponents of these visions advanced a new understanding of what legal history is and ought to be. They called upon jurists to engage with the historicity of the law and appealed to historians to both acknowledge the pervasiveness of law and recognize its particularities. Yet, despite the desire to bring law and history together again, these legal historians never claimed that the two pursuits were one and the same. Instead, and as discussed later, they wanted history to improve the study of law, and the study of law to improve history. They asked questions about the nature of legal history, and they advanced reasons for why being familiar with it would be important for both jurists and historians.

The first target identified by this new generation of legal historians was the traditional divide; a division retained by jurists and historians alike and that distinguished “law in the books” from “law in practice.” This divide, they argued, was the result of a misunderstanding of how law operates, among other things, because it assumes that law was the same as legislation and restricts its study to state-made normativity. Instead of following such a reductive reading, these legal historians defended the view that their task was to ask what the juridical value of certain phenomena was, what roles did law play in social formation, and how juridical grammar and technology affected reality. They envisioned the study of legal history as a pursuit meant to elucidate how a technology we now identify as “legal” was used to organize, arrange, and rearrange social relations, as well as grant words and actions a normative value that placed them in a hierarchy granting greater protection to some things over others. By employing methods of abstraction, and by constructing similarities and distinctions without ever losing sight of the concrete circumstances and contexts of each case, law’s final aim, they argued, is to propose solutions that would guarantee a certain equilibrium between conflict and consensus by legitimizing certain things but not others, or at least not to the same extent. As a result, any study of knowledge production, social practices, or power relations, to mention but three examples, needs to reflect on law (see Sections 1.3 and 1.4 and Chapter 3).

Asking about which actors were involved in each case, their rationale, how divisions and distinctions were constructed, as well as what kinds of answers the law supplied and how prescriptive they were, these legal historians conceived of the legal field as one in which everyone participates to some degree or another. Some actors might exercise more control, possess greater agency, or have a better understanding of how the legal system works, but no one lives outside the law or completely independent of it, not even those at the social extremes: the very privileged and the heavily oppressed.

Criticizing both formalism and statism, these legal historians also rejected legal nationalism, which presupposes that law is the product (and reflection) of a particular community or nation, as the German Historical School had once argued. Like legal humanists before them, they suggested instead that law, though always attentive to local circumstances, was also a technology that crossed political, ethnic, and national borders. Finally, these legal historians argued that law should not be studied as a separate body of norms that are completely autonomous and unrelated to other normative phenomena. Rather than imposed from the outside (as a statist formalist approach would lead us to believe), or forming a permanent and stable structure from within (as proponents of customary law presented it), they suggested that law, though varying to a great extent across time and geographies, is nonetheless a scaffold that seeks to give structure and meaning to human interactions, as well as acts as a means to arrange and rearrange them.

These views, which reflected a new understanding of the thematic field that legal history must cover, also insisted on the historicity of law. Accordingly, it is insufficient to ask about the historicity of a particular event, piece of legislation, or moment. To understand legal history, we must also consider how the legal context mutated, that is, how the legal framework in which different solutions operated differed over time. The task these legal historians adopted as their own was, therefore, to explain that law as a technology of conflict resolution had a history of its own, and that this history must be uncovered if we are to understand how law interacted with society. For example, medieval and early modern schemes for administrative work, they observed, can best be found in theories of judgment rendering and the history of the family, not in administrative correspondence or in royal decrees. Because the logic of past normative arrangements was so different from our own, to understand how they operated we must consider areas of legal research such as the juridical norms of the domestic sphere (see Section 3.3), religious normativity (see Sections 3.1 and 3.2), the legal valence of friendship and love, or even the jurisprudence tied to the various colors.Footnote 83

Remembering that not only particular solutions but also the legal context constantly mutated would have us ask, to mention yet another example, when did directum (the prior term for “law” in many European languages) supersede ius (the ancient Roman term) as the most immediate label designating “law”? What can this transition tell us about societal expectations across Europe, where this mutation took place in some areas but not in others? Why was justice (ius) tied to direction (dirigere as in directum) in certain times and places but not in others?Footnote 84 How can we understand the radically different ways in which certain documents were read over time, such as the emblematic Magna Carta, if we did not appreciate the constantly evolving contexts in which they were interpreted?Footnote 85

These observations were aimed at convincing readers that law itself is not an atemporal or ahistorical construct that could be discussed in the abstract as if it were the same unchanging phenomenon. If we already recognize that the meaning of law can differ from place to place, time to time, and according to who is observing, we must also remember that the role law occupies in society does not remain static, and neither does the precise technology it proposes or what it considers prescriptive.

For this group of scholars, it was particularly important to assert the specific character of the late medieval and early modern law, which they claimed was distinct from our present-day structures, though the opposite is commonly thought to be the case. Distinctiveness was not only tied to the obvious fact that specific solutions were different, but mainly to the fact that the basic assumptions regarding what law is, how it operates, what it is supposed to accomplish, how it pretends to intervene in society, and the relations it has with other normative and cultural spheres were vastly different. Late medieval and early modern law did not dictate solutions (see Sections 3.1 and 3.2); instead, it indicated which questions should be asked and what considerations should be taken into account. What law did, therefore, was to aid in making a just decision by advancing options, explaining variations, and imagining possibilities, all while giving actors a tremendous amount of discretion as to which road they take. In other words, law was a system in which a plurality of options existed, as well as a multiplicity of sources and authorities, all of which were equally valid and none a priori superior to the other.

The wish to problematize the past also led this group of legal historians to rebel against portraying it as consisting of “systems” that preceded one another in an orderly fashion.Footnote 86 Such a depiction implied a degree of regularity and unity that was largely absent. A “system” presupposed a hierarchy of sources, a clear catalog of values, and/or a singular rationality. Yet, medieval and early modern law featured a casuistic universe. Furthermore, the image of various systems preceding one another portrayed the development of law as a succession of schools and centers, as in the stereotypical depiction of European law: conceived in Italy, developed in France, and improved in Holland.Footnote 87 It also sent historians to “juridical traditions” that were supposed to communicate homogeneity and permanence as well as singularity and distinction when compared to all others. These legal historians argued that such images of the legal past undermined the important role of plurality, interpenetration, flexibility, and constant updating.Footnote 88 Proposing abstractions that were perhaps necessary for lawyers in their pursuit of resolving conflicts, they nonetheless entailed a form of violence that imposed on the past our present-day desire for clarity and certitude. Instead of searching for clear answers, legal history must describe the variety of voices, contrasting positions, and alternative proposals that, rather than depicting the past as “the kingdom of what is predetermined,” would demonstrate that it was “the theatre of possibilities.”Footnote 89

One of the remarkable results of this move to historicize not only legal application but also law itself was, for example, the preoccupation of this group of legal historians with the creation, administration, and imposition of categories. Who had the power to create legal categories? How prescriptive were they and how were they managed? How did the emergence of categories change society and societal processes? Identifying law as an essential instrument for creating, imposing, and debating distinctions between right and wrong, as well as between what could be considered efficient and useless, also led to the obvious observation that the greatest struggle in history was perhaps not so much for social and economic prominence but over the ability to create and impose norms. This, as Foucault would probably have argued, may seem a gentler way to order the world, but as a technique, it was no less powerful and no less violent.Footnote 90

The proponents of these views also took issue with practitioners, whom they accused of anachronistic approaches motivated not by ignoring change over time – most of them knew that laws and practices constantly mutated – but by the refusal to grant sufficient attention to what else had changed. They suggested that many jurists and historians employed a retrospective quest that mostly searched the present in the past by tracing its “roots” or “origins.” Others went to extraordinary lengths to justify or legitimize their preference of present-day arrangements, in some cases rendering the past incomprehensible or even ridiculous. Either way, this regressive history, which made the past look like the present, might have questioned institutions, laws, and practices, but it did not observe the legal system itself. By going down this road, proponents of this type of history argued for continuity where none existed, and they ignored all that was no longer relevant to the present or was simply too strange or too counterintuitive to digest.

While pleading that we remember that the legal framework, and not only individual solutions, was subject to mutation, these legal historians also advocated the need to take law seriously via a close examination of its logic. Law, they argued, may use words that seem comprehensible, but like all technologies that seek to influence reality, such words carry a tremendous amount of baggage – and this baggage needs to be taken into consideration when examining legal language. In other words, though it is essential to understand the conditions that led to the emergence of certain terms, ideas, categories, or practices, it is also vital to consider that all of them have the consistency of loose sand. Like all other words, and probably more so than most words, legal terms appear immobile and immune to change; however, in reality, they are constantly shifting.

Take, for example, an apparently straightforward term like “family.” While families may very well have always existed, the definition of a “family” has dramatically changed from a voluntary association of individuals in antiquity to structures we now conceive as based on blood relations. The meaning and extension of blood relations also constantly mutated: Whose blood mattered, how, why, and to what degree? Over time, law recognized radically different configurations of “family,” applying to them a series of changing rights and obligations as well as intervening in them to various extents and in a multiplicity of ways. The literal continuity of terms such as family, therefore, masked deep and constant changes, with “a radical discontinuity of sense lurking beneath the ostensible uniformity of worlds.”Footnote 91 To rescue family law, in other words, it is insufficient to show that rules regarding the family changed. It is necessary to inquire as to what a family was, who posed the question, why, when, where did the multiplicity of answers originate, and how prescriptive or discretionary were the answers.

If “family” as a right and obligation-bearing entity was a completely different affair depending on the place and time, to rescue its history would require not only knowing a great deal about the location, period, and actors but also take into consideration how law intervened in such debates by giving different factual constellations a juridical meaning. This meaning depended on facts, but it mainly operates by attributing to these facts a normative value and by asking about their juridical significance. By using the persuasive power of language, law employs words to obtain certain goals. Though law also uses coercion and violence, it mostly seeks to convince by using language – which is why, by definition, it always includes a variety of options and involves lengthy debates that the parties use to demonstrate why they are right and the others are wrong.

To understand how the term “family” was “normalized” in the sense that at different moments in time, it was granted different normative meanings, one would have to reconstruct these debates. Family, in other words, may be a term we presently take for granted, or some consider a natural institution, but if we keep in mind that in other periods it was conceived as a constructed, artificial unit, we maybe able to liberate ourselves from considering its existence or meaning a forgone conclusion. This would also remind us that, because law has a normalizing effect, and because this effect is always part of broader discussions, the terms it uses are an open sesame that invites scholars to unfold what is otherwise unseen. Family operates in this way, but so do many other placeholders such as intention, customs, immemoriality, or consent.

Of course, one could argue that these placeholders only operate within a restricted field established by jurists or juridical experts. Yet this conclusion would defy all that we observe in society – both past and present. In this transformative process of facts to phenomena with normative value, particular traditions and practices matter, and they matter not only to jurists but also to contemporaries who use the law. How else can we explain the claims of illiterate peasants that they had to resist incursions on their territory by neighbors or else their silence would be construed as consent?Footnote 92 Alternatively, how can we understand why a plethora of individuals, unable to prove what they wanted, invoked immemoriality? They knew that it was a powerful tool even if they did not know why.Footnote 93

In this quest to refashion legal history, these Latin American, Spanish, and Portuguese scholars refuted the claim that the history of ideas was a legal history or that legal historians can stop at describing how norms evolved. They lamented the propensity by which actors invoke history to make claims in the present, and they expressed a desire for a legal history that would transcend national boundaries and be guided by the entities that were relevant in the past, not the present. They would ask questions such as: Was there a colonial law or is this law tied to our current needs and therefore a fiction of our imagination? Would it not be more appropriate to ask about transfers, translations, and exchanges as well as follow practices and processes of analysis and determination as they crossed the oceans than create categories a priori? (see Sections 1.3, 1.4, and 3.1 and Chapter 4).

If how to study legal history was a major issue for these legal historians, another involved the role it should play. In the past, these scholars argued, legal history mainly served either to strategically legitimize or criticize existing structures. Legal humanists strove to employ the power of local law against both universalistic tendencies and the increasing powers of kings. In nineteenth-century Germany, legal history served to justify as well as facilitate both German unification and debates regarding the character of German law. The instrumentalization of history to support political projects is, of course, a very common phenomenon. However, in the case of legal history, they argued, it has a particularly pernicious effect because this use reinforced the tendencies to portray legal evolution as linear and foretold. It often transformed the past into a repository of either better times to be recaptured or horrible times to be avoided.Footnote 94

Rather than justifying or explaining the present – as many have done in the past – these scholars encouraged practitioners to transform legal history into a space of critical observation. They argued that recognizing legal historicity and the extreme alterity of the past should enable us to imagine alternative and unexpected routes in the present as well.Footnote 95 Instead of looking into a mirror, legal history could force us to look at familiar things from a different perspective – one that would question, rather than confirm, our present-day biases. For legal history to do so, we must seek not only to record but also to explain in the etymological sense of ex-plicare: the unfolding and revealing of hidden aspects that were either too obvious or too consensual for contemporaries to even mention, let alone elucidate.Footnote 96 According to this usage, it would be often more important to ask questions than to answer them, to express doubts than to look for certainties.Footnote 97 Thereafter, the goal would be to “make and unmake history” (fazer e desfazer a história) while also constructing and deconstructing the law.Footnote 98 This quest would transform the study of sources into an instrument rather than an end in and of itself.Footnote 99 The same could be said of episodes and events.

The extent to which these calls have been heeded remains to be seen. Though communication between jurists, historians, and legal historians has intensified in recent decades, and indeed legal history seems to be everywhere, formalist legal history remains popular, and there are still plenty of books that describe the legal past with certitude, reconstructing rules rather than possibilities, norms rather than discussions.Footnote 100 Meanwhile, many historians continue to either dismiss law altogether or consider it an external scaffolding rather than an internal spinal cord of all social interaction.Footnote 101 Perceiving law as a superstructure and believing that the social, political, or economic could be reconstructed by ignoring or at least marginalizing the law, many historians, who are otherwise extremely sensitive to historical contexts, nevertheless fail to contextualize and historicize the law. They adhere to a very narrow understanding of the law, equating it with present-day structures, or they implicitly use law as a synonym for state legislation in periods that, paradoxically, predated the emergence of states. Many also frequently assume that law prescribes solutions, that the words it employs have an obvious meaning, or they imagine that interpreting law to one’s advantage is a form of resistance. As a result, otherwise incredibly respectful historians can confuse ancient Roman law with the Roman law that Europeans brought with them to the Americas (the revived medieval Roman law that formed part of the ius commune and that was largely distinct from ancient Roman law). Or, alternatively, they arrive at conclusions pointing out that certain actors (but not others) used the law as a “resource” rather than a “script” or that actors could choose and pick what to follow.Footnote 102 They suggest that the distinctions we currently maintain between state and international law (or inter-polity) had always been meaningful, and they express surprise when “internal” law affects “external” developments.Footnote 103 Many historians also routinely insist on a gap between law and its application, that is, “law in the books” versus “law in action.” This allows them to see lawlessness and corruption or, on the contrary, agency where none exists. Where others see a soccer match, they only see many individuals running aimlessly after a ball.Footnote 104

. . .

1.3 How Is Law Produced?