This volume traces processes associated with the creation of large-scale political entities and networks of exchange, within a time frame that builds on and expands the usual limits of the classical era. It considers the formation and expansion of states and empires, and the attendant economic, political, social, cultural, and intellectual developments in various regions of the world. It explores these processes at three interacting scales. At the global scale, the initial chapters provide an overview of the key economic, political, social, cultural, and intellectual developments that occurred between 1200 bce and 900 ce. Chapters at the interregional level focus more tightly on developments in a number of clearly defined political and cultural entities within the four distinct world zones of the period – Afro-Eurasia, the Americas, Australasia, and Oceania. These interregional perspectives are then complemented by a series of regional studies, which use a “close-up” view of events to illustrate the developments and patterns identified at the interregional and global scales. This introductory chapter offers a brief global-scale overview of some of the key developments in the evolution of states, empires, and networks between c. 1200 bce and c. 900 ce.

Introduction

When the sun rose above the eastern horizon on the first day of the year world historians designate as 1200 Before the Common Era (bce), its rays progressively illuminated the continents and oceans of earth. As the world spun on its axis, light spread westwards across the face of the globe, and night gave way to day. The earth was almost 4.6 billion years old, one of a number of planets and smaller objects orbiting an obscure, medium-sized star in the spiraling Milky Way Galaxy, home to perhaps 200 billion other stars. Yet of all the planets, moons, and asteroids in the solar system upon which the sun shone that day, only one was known to be home to life, which covered its surfaces and deeps in teeming variety. Each one of these countless organisms was a product of evolutionary processes that had begun with the emergence of archaebacterial life forms some 3.8 billion years earlier, and each was perfectly adapted to the environmental niche in which it dwelt. Although all of these life forms were extraordinary in their own way, one relative newcomer had proven exceptionally versatile since making its modest appearance somewhere in Central Africa 200,000 years earlier, and which now occupied every continent on earth with the exception of Antarctica. It is with the affairs of this species – Homo sapiens (or “wise man”) – between c. 1200 bce and c. 900 ce that this volume is principally concerned. In this introductory chapter we unfold the events of that period as though they took place in a single day, from “sunrise” in the Year 1200 bce to “sunset” more than two millennia later in the Year 900 of the Common Era (ce). Homo sapiens are a product of hominid evolution, a unique bipedal species descended from some common ancestor of both apes and hominids that lived approximately 7 million years ago. As a result of geographical isolation through earthquake or some other natural event, a small group of hominids had found themselves isolated and following a different evolutionary path to other members of their homininae genus. The result was the emergence of a large-brained hominine, Homo sapiens, which possessed specialized cognitive abilities that eventually facilitated the acquisition of complex, symbolic language. This had given Homo sapiens an adaptive advantage that had allowed them to prosper and spread at the expense of their closest hominine relatives, Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalis. By c. 27,000 years ago only one type of hominine remained on the planet – Homo sapiens – already distinguished as one of the most remarkable, but also most dangerous, species on earth.

After pursuing a nomadic, hunter-foraging lifeway for 190,000 years or so, some groups of humans had adopted agriculture and sedentism from c. 9000 bce, an “agrarian revolution” that set human history off upon different trajectories. In those regions where agricultural lifeways were pursued, some villages evolved into towns and cities, and by c. 3200 bce complex societies had emerged in southwest Asia and northeast Africa. In the centuries that followed, the increasingly powerful leaders of these early states learned to control larger regions and more and more resources, until by c. 1200 bce huge agrarian civilizations, each ruled by coercive political structures called “states,” controlled substantial portions of the Afro-Eurasian world zone. Historians have traced the experiences of these agrarian civilizations across large scales of time and space. Many of the chapters in this volume are concerned with the history of these civilizational structures, the cities and states that sustained them, and the networks of exchange that connected them together into vast webs between c. 1200 bce and c. 900 ce.

In many other regions, however, humans had continued to follow the foraging, nomadic lifeways of our ancestors and had not even adopted agriculture and sedentism, let alone states and civilizations. It was the agricultural revolution that created different human histories, then, because the hitherto shared and common global experience of hunting and foraging that continued in some regions was replaced in others. In parts of Afro-Eurasia and later the Americas, historical change began to occur at a faster pace and on larger scales than was the case in, for example, Australia, where aboriginal people continued to pursue their perfectly adapted foraging lifeways. As the sun rose on the first day of the year we now think of as 1200 bce, some 8,000 years after the first appearance of agriculture and sedentism, this extraordinary variety of human lifeways was very much in evidence.

Setting aside the fact that on the first day of January of any new year the sun is shining continuously above the frozen continent of Antarctica, the sun’s first rays fall initially upon a part of the earth just to the west of the International Date Line, an imaginary line extending north–south across the Pacific Ocean. Dawn then progresses from east to west, with the moment of sunrise being recorded according to a series of local time measurements. The first point of land to be touched by the light would probably have been a headland near Victor Bay in Antarctica, but in 1200 bce this was a place completely uninhabited by humans. Further north, however, early sunlight found the mountains, forests, and coral-fringed beaches of thousands of scattered Pacific islands, many of which were most certainly occupied by humans.

Oceania world zone

This occupation was a result of the most extraordinary maritime migrations in human history, which occurred largely within the 2,100-year period of principal interest to this volume. Sometime around 1500 bce migrants from the Tongan and Samoan island groups had begun a series of lengthy ocean voyages in large canoes. Navigating by the stars, these mariners settled in parts of the Cook Islands and Tahiti-nui. A later wave of migration resulted in the spread of these Polynesian peoples as far east as Rapa Nui (Easter Island) by 300 ce, and as far north as Hawai’i by 400. A third wave of migrations occurred late in our “day” when groups from the Cook or Society Islands eventually settled Aotearoa (New Zealand) in the ninth century. By the time European explorers began to survey the Pacific in the sixteenth century, Polynesian and Melanesian peoples had occupied virtually every single habitable island in the Pacific.

The inhabitants of these widely scattered islands practiced a variety of lifeways somewhere along the continuum between nomadic foraging and sedentary agrarian states. Archaeological evidence reveals distinctive Polynesian agrarian and fishing technologies in most of the island groups, based on the successful domestication of plants like taro, breadfruit, banana, coconut, and sweet potato, and of animals including the pig, dog, and chicken. On Rapa Nui and Hawai’i, coercive leaders emerged to control state-like structures complete with most of their defining characteristics – monumental architecture (notably the Ahu of Rapa Nui), the accumulation of surpluses, and inter-tribal conflict. Rapa Nui also provides early evidence of the potential for humans to self-destructively impact the natural environment. Encouraged by their chiefs, intra-village competitive monument building (again of the Ahu) resulted in the impoverishment of a previously vibrant society through rapid deforestation. Yet on Rapa Nui and elsewhere, sunrise on any day late in the chronology of our volume would have found hundreds of thousands of farmers and fishermen, leaders and servants, warriors and builders, all going about their business upon the forest-covered islands, atolls, and deep-blue surface of the Pacific.Footnote 1

Australasian world zone

The harsh southern hemisphere summer sun next beat down upon the highlands of New Guinea, and the plains and bush-covered regions of Australia, a vast continent located along the southwestern edge of the Pacific Basin. To the casual observer of this world zone, time might appear to have stood still. In the jungles of New Guinea, which humans had begun to occupy perhaps 60,000 years earlier, farmers had been following early agrarian lifeways based on small-scale horticulture and slash-and-burn technologies since perhaps 5000 bce. There were villages aplenty in the forests, but none of these had evolved into towns or states, and power in these communities was still consensual rather than coercive. Yet agricultural practices were sophisticated; some agri-historians believe that New Guinea farmers understood the principles of crop rotation, mulching, and tillaging long before Eurasian farmers did.

In Australia, the ancestors of the aboriginal people had arrived by sea from Southeast Asia 50,000 years earlier, demonstrating advanced boat building and navigational skills that had made them amongst the most technologically sophisticated people on earth at that time. By c. 1200 bce the aboriginal population numbered anywhere between 300,000 and 750,000, with the densest concentrations living in the southeast of the continent. Their languages were many, up to 750 different dialects, although similarities in the phenome sets indicate a probable single common origin. The variety of dialects might also suggest a wide range of lifeways, but to our casual observer daylight revealed indigenous Australians engaged in a set of semi-unified cultural practices.

Whether in the arid interior of Australia, in the great tracts of eastern bushland, or along the coasts, the overwhelming majority of aboriginals remained semi-nomadic hunter-foragers from the time they first migrated to the continent until the arrival of Europeans. Each group had its own traditional territories, which were defined by geographic markers like rivers, mountains, and lakes, and the well-being of these lands was fundamental to the success of the people. Indigenous Australians “cared” for their environments in the manner of foraging peoples everywhere, although paleo-aboriginals unwittingly contributed to the extinction of many large animal species in Australia, and their practice of fire-stick farming helped lead to the eventual desertification of much of the continent. There were some exceptions to this nomadic lifeway, like the Gunditjmara people of Western Victoria, who supported a semi-sedentary lifeway through eel farming. Archaeologists have found the remains of hundreds of permanent huts, 75 square kilometers (45 square miles) of artificial channels and ponds for farming the eels, and trees used for smoking the product to facilitate its transportation to other parts of southeast Australia.

With the exception of the Gunditjmara, any dawn across Australia during our two-millennia “day” would have revealed small groups of humans fishing with fishbone-tipped spears; others hunting kangaroos with wooden weapons like the boomerang or woomera spear-thrower; and yet others (particularly women) using wooden and stone digging sticks to access nutritious roots and insects living just below ground. At a number of sacred sites across the landscape, elders prepared to pass on oral creation stories from the Dreamtime, when humans, animals, and spirits all emerged and peopled the land. Critical to the spiritual practices of indigenous Australians were music and dance, and both men and women had been up since dawn, preparing to perform ritualized dance-like ceremonies, accompanied by vocalists, percussionists, and musicians, at large ceremonial gatherings called corroborees, where goods, ideas, and marriage partners would also be exchanged.Footnote 2

Afro-Eurasian world zone

As the corroborees were gathering in the Australian outback, further to the north sunrise drew steam from the dense jungles of Southeast Asia, on the fringes of Afro-Eurasia. The adoption of agriculture in multiple places across this vast world zone had led to the emergence of cities, states, dense populations, professional leaders, military, and religious elites, and complex intra- and interstate political relations that would have seemed utterly alien to Pacific Islanders and Australian aboriginals. Given the political focus of our volume, this brief survey will identify the key developments in state and empire construction that occurred between c. 1200 bce and c. 900 ce, and highlight the critical networks of exchange that developed between all the different types of human communities that populated the Afro-Eurasian world zone.

Humans had occupied the islands and mainland of Southeast Asia since Paleolithic times, and during the centuries preceding 1200 bce they had gathered together into a range of agrarian communities. The country known today as Vietnam developed its own distinctive culture during the first millennium bce, but from the moment the Qin Dynasty unified much of China in the third century bce, Vietnam had been seen by the Chinese as an almost inevitable part of their empire. After being colonized by the Han Dynasty soon afterwards, the Vietnamese decided to adopt important cultural ideas from the Chinese, including Confucian and Buddhist ideology, but also to fiercely resist political assimilation. This resistance came to fruition late in this volume’s day, and by 939 the Vietnamese had won a political independence they were destined to keep until French colonialists turned up in the nineteenth century.

A powerful state, based on political and commercial control of the narrow Isthmus of Kra, also developed in Malaysia, where the rulers of Funan used Indian models of power to declare themselves rajas. After the fall of Funan in the sixth century, leadership of the region passed to the Srivijaya state on the island of Sumatra, which constructed a formidable navy that dominated the port cities of Southeast Asia between 670 and 1025 ce. Once in control of all the major sea lanes, the rulers of Srivijaya grew wealthy through their role as intermediaries in the thriving spice routes trade between India and China, itself part of a much wider Afro-Eurasian maritime network of commercial and cultural exchanges that had been flourishing since the first millennium bce. By the tenth century ce, the Srivijaya capital of Palembang was a thriving commercial hub in which merchants from many ethnicities and belief systems went about their lucrative daily business amongst the docks and warehouses of the port. On the mainland meanwhile, in present-day Cambodia, the Khmer people were in the process of constructing a soon-to-be powerful kingdom known as Angkor, which would rule for more than 500 years and erect, at Angkor Thom and Angkor Wat, two of the most extraordinary religious complexes in world history.

North again, along the western shores of the Pacific, the thousands of islands of the Japanese archipelago were also enjoying the “rising sun,” a symbol that in the seventh century ce inspired rulers Tenmo and Jito to actually name their country Nippon – the “base of the sun.” Humans had come to Japan perhaps 35,000 years earlier and had eventually made the transition from foraging to farming. During the first millennium bce, migrants from Korea introduced new pottery, technologies, and lifeways to create the Yayoi Culture. Rice agriculture expanded throughout the islands, leading to increased populations and the appearance of social hierarchies and coercive power structures. In the third century ce, one of these rulers had been a woman, the enigmatic shaman Queen Himiko. The power of Himiko and the other rulers of the period is still visible today in the massive tombs they left behind. However, it was the arrival of Buddhism and its accompanying hierarchy, along with the promulgation of laws and a constitution by Prince Shotoku early in the seventh century, which really consolidated and centralized power in Japan, until a fully fledged imperial court system was in place in the great wooden city of Nara. In 794 a decision was made to build a new capital at Heian in modern Kyoto, a city destined to be the capital of Japan for the next thousand years. But just as the sun was setting on the ninth century, the authority of the Heian emperor was being superseded by members of the Fujiwara clan, who functioned as the real power behind the Japanese throne until late in the twelfth century.Footnote 3

In the Korean Peninsula, to the west across a narrow strait from Japan, the process of building a unified state had been similarly complicated. Paleolithic migrants had practiced hunting and foraging for perhaps 50,000 years, until the adoption of agriculture had led to increased populations and villages. Bronze technology appeared in the first millennium bce, but it was the introduction of iron tools and weapons in the second century bce that dramatically increased agricultural productivity. At about the same time, as with Vietnam, the Chinese had come to regard the Korean Peninsula as part of their domain, and for almost 400 years much of Korea had been a colony of the Chinese. In the midst of this, three regional kingdoms emerged, Paekche, Koguryo, and Silla. By 313 ce the northern Koguryo kingdom had driven the Chinese out, but this only led to centuries of bitter conflict between the three rival states during the ensuing “Three Kingdoms Period.” Indeed, seemingly endless interregional and trans-regional conflict characterized the history of much of Afro-Eurasia throughout virtually all of the period covered by this volume.

Ongoing tensions between Koguryo and the Chinese helped the southern kingdoms of Silla and Paekche grow stronger. Archaeological evidence shows an increase in social hierarchy in burial practices, and also the emergence of intense specialization in pottery manufacturing by an artisan class under elite patronage. Each of the three ruling dynasties adopted Buddhism, although Confucianism and Daoism were also widely practiced. The Chinese Sui Dynasty attempted to invade Korea in 612, but Koguryo forces killed thousands of Chinese troops and inflicted a defeat on the Chinese so humiliating it contributed significantly to the demise of the Sui. Eventually Silla forged an alliance with the Chinese Tang Dynasty (618–907 ce), which resulted in the defeat of the other two kingdoms. The Tang then attempted to recolonize Korea, but this was thwarted by Silla, who went on to unify and rule southern Korea until late in the ninth century. But at the end of our “day,” early in the tenth century, two powerful generals, Wang Kon and Kyonwhon, were engaged in a virtual civil war, which led to the abdication of the last Silla king in 935 and his replacement by Wang Kon and his new Koryo Dynasty, the state that gave the modern nation of Korea its name.Footnote 4

On the mainland of East Asia, morning sunlight in c. 1200 bce illuminated the astonishing geo-diversity of China: a 9,000 mile coastline dotted with thousands of islands, two of the greatest river systems on the planet, steppe grasslands in the north, tropical wetlands in the southeast, inhospitable deserts, and great mountain systems that include seven of the world’s fourteen highest peaks in the west. By 1200 bce these environments were already home to an ancient and complex civilization. Early farming communities along the Yangtze and Huang He river systems had evolved into a series of sophisticated cultures like Yangshao and Longshan, a process that by the late third millennium bce led to the appearance of powerful dynastic states such as the Xia, Shang, and Zhou. But Zhou central rule, so stable and impressive for the first 500 years, collapsed in the sixth century bce to be replaced by half a millennium of bitter conflict. It was during this age of “warring states” that hundreds of schools of political and ideological thought developed in China, from which the three great philosophies of Confucianism, Daoism, and Legalism emerged to guide Chinese political and religious thinking for the millennia that followed.Footnote 5 During the third century the most powerful of the warring kingdoms used Legalism to secure victory over its rivals and reunify much of China in the name of the Qin Dynasty (221–206 bce).

The brief period of Qin rule paved the way for the Han Dynasty (206 bce –220 ce), which used a combination of the three ideologies, but particularly Confucianism, to build a well-organized and wealthy bureaucratic state. It was also during the Han dynastic era that China became connected for the first time with the rest of Afro-Eurasia via the Silk Roads, the greatest trade and cultural exchange network of the premodern world. The involvement of the Chinese in Silk Roads trade meant that virtually every state, nomadic confederation, small-scale agrarian community, and even remaining hunter-gatherer bands in this vast world zone were now connected into a single exchange network for the first time in history.Footnote 6

During the third century ce, Silk Roads trade declined dramatically as the key players in the network – the Han, Kushans, Parthians, and Romans – all withdrew. The Later Han suffered from a dearth of effective leadership, and a series of peasant uprisings led to the demise of the dynasty in 220, and to centuries of internal disunity and conflict. The first emperor of the Sui Dynasty (581–618 ce) ended this “Age of Disunity,” but the abortive campaign against the Korean Koguryo kingdom noted above, and a massive “Grand Canal” engineering project completed by the second Sui emperor Yangdi, fostered so much resentment that the emperor was assassinated in 618.

A Sui governor named Li Yuan instituted a new dynasty, the Tang, which went on to rule China for the next three centuries. The Tang organized China into a powerful, prosperous, unified, and culturally sophisticated imperial state. The Early Tang Era was marked by strong and benevolent rule, successful diplomatic relationships across much of Eurasia, economic and military expansion, and a rich cosmopolitan culture that resulted in the production of superb literature and visual art,Footnote 7 and also in increasingly complex and sophisticated relations between men and women.Footnote 8 It is probably no exaggeration to suggest that during the Tang Dynasty China was the wealthiest and most powerful state thus far seen in world history. Tang wealth and stability ushered in another great age of commercial and cultural exchange across Afro-Eurasia. As we will see below, Tang control of Eastern Eurasia corresponded with the Islamic caliphates (and to a lesser extent the Byzantine Empire) gaining control of much of Western Eurasia. With strong, commercially minded states also in place in Central Asia, material goods, ideas, and diseases flooded back and forth across the world zone in a second great Silk Roads Era, which continued to operate, although with lesser intensity, even after the collapse of the Tang in 907.Footnote 9

North and west of the mountain ranges and deserts that had kept China isolated from Central Asia for millennia were the great steppe grasslands, the realm of pastoral nomads who played a vital role in facilitating exchange between empires and states throughout much of the period of this volume. Pastoral nomads formed communities that lived primarily from the exploitation of domestic animals such as cattle, sheep, camels, or horses. The appearance of burial mounds across the steppes of Inner Eurasia shows that some of these communities became semi-nomadic during the fourth millennium bce. By the middle of the first millennium bce, several large pastoral nomadic communities had emerged with the military skills and technologies, and the endurance and mobility, to raid and even dominate sedentary agrarian states and empires. Some of them, such as the Saka, Xiongnu, and Yuezhi, established powerful confederations that controlled the vast steppe lands between civilizations.Footnote 10 Because they could survive in the deserts and mountainous interior of Inner Eurasia, it was the nomads who facilitated the linking up of all the different lifeways and communities. Ultimately, it was the role of pastoralists as facilitators and protectors (as well as periodic raiders) of mercantile exchange that allowed the Silk Roads and other networks to flourish.Footnote 11

In the middle of the first millennium ce, new groups of Turkic-speaking pastoral nomads appeared on the scene, who were destined to have a profound impact on enormous areas of Eurasia. References to the Turks in sixth- and seventh-century Chinese sources describe a great Turkic empire stretching from Mongolia almost to the Black Sea. This Oghuz Empire was forced to accept Tang Chinese hegemony in the seventh century, leading to the migration of different groups of Turks out of Central Asia toward the west. In the centuries that followed, migrating Turks established political structures all across the region and exerted a powerful influence upon states within the Byzantine, Islamic, and Indian realms.Footnote 12

The Indian subcontinent lies far to the south beyond the high Tibetan Plateau and even higher Himalaya, and daylight in the Year 1200 bce highlighted a fragmented polity of small kingdoms and competitive states. Between c. 2600 and c. 1900 bce, the Indus Valley in the northwest of the subcontinent had functioned as a vibrant and unified political, commercial, and cultural zone historians now call the Indus civilization. But following the collapse of the Indus civilization, the millennium-long Vedic Age that followed the arrival of Indo-Aryan migrants in c. 1500 bce was characterized by political disunity as numerous regional rajas (kings) jostled for power. In the fourth century bce, the defeat of one of these local kings by the adventurer Alexander of Macedon facilitated the rise to power of Chandragupta Maurya, who went on to unify much of India under the Mauryan Empire (332–185 bce). After the death of Chandragupta’s grandson Ashoka, the Mauryan Empire entered a period of economic decline, and by 185 bce it had collapsed. Much of India was fragmented again for the next five centuries, although in the north nomadic invaders established their own states that controlled large areas of India, such as the powerful Kushan Empire (c. 45–250 ce).Footnote 13

Imperial rule and unification returned to India with the establishment of the Gupta Empire (c. 320–414 ce). Founder Chandra Gupta (no relation to the Mauryan emperor) created a dynamic kingdom in the Ganges Valley that his successors expanded until it approached the territorial size of the Mauryans. The great Mauryan capital city of Pataliputra was revived as the imperial capital, and stability returned to most of the subcontinent north of the Deccan Plateau. Mauryan centralized imperial administration was replaced with a more decentered form of provincial government by the Guptas, who presided over a cultural and intellectual “golden age.” But after having to deal with an invasion by the nomadic Hephthalites in the fifth century, the Gupta realm slowly contracted and eventually disappeared. A brief attempt to reunify the subcontinent was made by Prince Harsha (r. 606–648), but local rulers had amassed too much regional power to accede to a single, central authority. Following Harsha’s death at the hands of an assassin, India reverted to a divided realm before the arrival of Islam in the ninth century ushered in a new stage of commercial vitality but also political and religious tension.Footnote 14

Back north of the Himalaya to the western regions of Central Asia and the Iranian Plateau, which had long functioned as a natural crossroads through which numerous migrating hominids had passed, including both Homo erectus and Paleolithic Homo sapiens moving out of Africa. In the early second millennium bce, traders and irrigation farmers had constructed an important series of commercial state-like structures known today as the Oxus Civilization.Footnote 15 Different groups of pastoral nomads also migrated into the region, notably the highly militarized Saka, also the Medes and Persians. In the sixth century bce, under the leadership of Cyrus (r. 558–530 bce), the Persians set out on a series of expansionary campaigns and built a vast Achaemenid Empire that eventually stretched from Afghanistan to Greece. Controlling an area of some 3 million square miles, or more than 10 percent of the land surface of the earth, this was the largest agrarian civilization the world had ever seen. The Achaemenids overreached themselves by launching an attack on the Greek peninsula and a Persian army sent by Darius in 490 bce was defeated on the plains of Marathon. Ten years later, Darius’ successor Xerxes invaded Greece with probably the largest military force ever assembled to this point in world history, but the Spartans famously forestalled the Persians at Thermopylae, and the Athenians destroyed the Persian fleet at Salamis. It was Alexander of Macedon who eventually brought an end to the Achaemenids with his victory over Darius II at Gaugamela in 331 bce.Footnote 16

But this was not the end of Persian domination of Iran and Central Asia. The Achaemenids were succeeded in the region by two more powerful Persian empires, those of the Parthians (247 bce – 224 ce), and the Sasanians (224–651 ce). Under Mithridates I (r. 170–138 bce) the Parthians used their considerable military skill to build an imperial state that extended from the eastern edge of the Iranian Plateau down into the flat lands of Mesopotamia. By maintaining a reasonably stable empire for so long, the Parthians helped facilitate high levels of cultural exchange across Afro-Eurasia during the first Silk Roads Era. The Sasanians also constructed an enormous imperial state that acted as a geographic bridge between China and the West, and a chronological bridge between the ancient civilizations and the new Islamic states that went on to control these vast arid lands.

In the seventh century ce, much of West and Central Asia came under the control of these new Islamic states, with the Abbasid Caliphate in particular (750–1228 ce) providing stability and cultural unity across an enormous Afro-Eurasian realm. The lightning-fast expansion of the Dar al-Islam (Abode of Islam) was unprecedented, even during an era in which great empires grew rapidly to enormous size. Expanding out of a small area of the Arabian Peninsula, by 637 Syria, Palestine, and all of Mesopotamia had fallen to Islam; during the 640s so did much of North Africa; and by 651 the Sasanian Empire had also fallen to Muslim armies. Expansion resumed early in the eighth century, into northern India in 711; and to the Atlantic coast of Morocco, then across the Straits of Gibraltar and into Spain by 718. The Abbasid Caliphate put in place centralized bureaucracies, minted coins, controlled taxes, and maintained a standing professional army. With a steady flow of tributary revenue coming in from all over the Islamic world, Baghdad was beautified with magnificent buildings, mosques, and squares, and by the end of our volume’s era it was one of the great commercial, financial, industrial, and intellectual cities of the world.Footnote 17

Dawn on the islands and glittering waters of the Mediterranean Sea illuminated a region that Phoenicians, Egyptians, Minoans, and Mycenaeans had all used to conduct trade and occasional conquest. The Phoenicians established small commercial city-states and a host of colonies through the Mediterranean region, and used these to conduct lucrative regional trade for four centuries between c. 1200 and 800 bce. The Minoans, based on the island of Crete, had also been commercially and culturally active, but by 1100 bce they were under the control of Mycenaean raiders from the mainland. There followed a period of mysterious collapse across much of the Mediterranean, but by the ninth century bce the Greek communities were in the process of constructing a new, vigorous commercial and cultural society based on a series of poleis or city-states, that eventually spread by colonization across the entire Mediterranean Basin.Footnote 18 But the Greeks, despite their extraordinary cultural, philosophical, and scientific achievements,Footnote 19 were never politically unified, and after successfully defending themselves against the Persians through a rare display of collective response, Classical Greek civilization essentially self-destructed through a bloody civil Peloponnesian War. It was this conflict that facilitated the rise of Philip VI of Macedon and his son Alexander, who embarked upon a campaign of personal conquest and, as we have seen, helped destroy the Achaemenid Persians and also made possible the unification of India under Chandragupta.

Toward the end of the first millennium bce, most of the Mediterranean Basin and adjacent inland regions came under the control of the Romans, who went on to establish an enormous state that controlled large regions of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa for centuries. According to the terms of the first constitution of 509 bce, the Roman state functioned as a republic administered by Consuls and a Senate, although additional officials, including two “tribunes of the people,” were later added. The republican system worked well for a time, but the growth in size of the state and the appearance of powerful men with private armies led to a century of civil war until Augustus claimed power as the princeps or “first man in Rome.” The princeps quickly transitioned into an emperor, and for the first half of the first millennium ce Rome was a vast imperial state that used slavery much more extensively than any other state during this era.Footnote 20 But the political unity of the early empire began to unravel following the migration into the Western Roman Empire of Germanic tribes in the third century ce. With the empire under pressure, the Emperor Constantine decided (early in the fourth century) to divide his realm into two, and while the western half came under continuing stress, the eastern realm prospered from its new capital at Constantinople.Footnote 21

The city of Rome was sacked by Gothic raiders in 410 ce, and again in 455 by a Vandal raiding party crossing from North Africa. These and other Germanic tribes then settled across much of the former Western Roman Empire, where some like the Franks and Angles established long-lasting kingdoms. Historians used to date the “fall of the Roman Empire” to the year 476 ce, when one German Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustulas, was killed by another, Odovocar. Historians today prefer to avoid terminology and periodization that articulates clean breaks and to use a more nuanced phrase like “the world of later antiquity” to describe processes that continued in the region into the second half of the millennium. During this period different forces, secular and sacred, struggled for ascendancy. The Catholic Church played an increasingly important role as the Pope in Rome attempted to assert both spiritual and political authority. In the late sixth century, missionaries of Pope Gregory were sent to Britain to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. The structure established in Britain by Gregory’s missionaries (with bishops supervised by archbishops, who in turn answered to Rome) became the standard model for church administration, and thereafter the Catholic Church functioned almost as a state within the wider framework of regional political states.

In an attempt to reestablish a stable political state in the former Western Roman Empire, the kingdom of the Franks forged an alliance with the Church in the sixth century, and by the time of his death in 511, the Frankish king Clovis I had succeeded in uniting the Franks and creating a Merovingian Dynasty in southern Gaul. A very able descendant of Clovis, Charles the Great (Charlemagne, 742–814), later established a substantial Carolingian Empire that managed to reunify much of Western Europe under strong central government. But the empire was fleeting, and following Charlemagne’s death it was divided between his three grandsons. As the “day” of our volume drew to its close, much of Western Europe was about to come under deadly attack from Vikings, Magyars, and Saracens, creating a crisis that would lead to the establishment of strong national European states in the centuries that followed.Footnote 22

While the former Western Roman Empire remained essentially fragmented, the Eastern Empire went from strength to strength. Constantine’s selection of the strategic and highly defensible site of Constantinople (Byzantium) for his new capital helped ensure that Greco-Roman culture was preserved for another thousand years in what became known as the Byzantine Empire (330–1453 ce). In the sixth century the Emperor Justinian carried out a tremendous urban renewal of the capital following a disastrous earthquake, and until its eventual sacking at the hands of Ottoman Turks in 1453, impregnable Constantinople was called the “the fortress of the world.” But the survival of the Byzantine state was never a sure thing. Some emperors were literally driven insane by the problems they faced, including invasions by Avars and Bulgars, sustained attempts by Islamic armies to destroy the empire, and bitter religious schisms over icons and disagreements with the Pope in Rome. However, for much of the ninth and tenth centuries that conclude our volume’s chronology, the Byzantines enjoyed a “golden age” of political stability, commercial vitality, and cultural sophistication.

Of increasing interest to the Byzantines were the forests and swamps to the northeast of their empire, the realms of Slavic peoples who were pushed onto the historical stage by the migrations of Central Asian peoples in the fifth and sixth centuries. Slavic peoples followed lifeways that included slash-and-burn horticulture, hunting in the deep forests, and trading forest products like honey, wax, and furs. But Slavic communities were increasingly conquered and controlled by a number of external groups, with both their political and their spiritual allegiances fought over by competing versions of Catholic and Orthodox Christianity, and by Islam. The Slavs were destined to play a critical role in the history of Russia, Ukraine, and Eastern Europe, and by the end of the millennium had already organized themselves into a series of regional states.

South again now, south of Europe and the Mediterranean, we follow the line of light into the vast continent of Africa, which even by c. 1200 bce had been an integral part of Afro-Eurasian trade and cultural exchange networks for millennia. Africa is a continent of extraordinary ecological and geographical diversity. The northern regions are dominated by the Sahara Desert, which stretches from the Atlantic Coast to the Red Sea and has been home to nomadic Bedouin peoples for thousands of years. The northeastern corner of Saharan Africa was the location for one of the oldest civilizations in all world history, Ancient Egypt. By c. 1200 bce Egyptian civilization was already approaching the end of its third major chronological period, which historians call the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1150 bce). The powerful pharaoh Rameses II had just concluded a campaign of vigorous conquest in Palestine and Syria, but following his death in 1224 the state fragmented and suffered invasions by Libyans, Kushites, and Assyrians. The end of Egyptian independence came in 525 bce when Egypt was incorporated into the Achaemenid Persian Empire; by late in that same millennium, Egypt had become part of the Roman Empire.Footnote 23

Despite the success of Egyptian civilization in using the Nile River to tame the harsh Sahara, the most hospitable environment for humans in the African continent is the great savannah grasslands where early hominids and Homo sapiens had evolved and flourished. Along the line of the Equator lies dense tropical rainforest, occupying some 7 percent of the continent. The jungle is less conducive to agriculture and grazing, but human communities had learned to survive and prosper there through foraging, hunting, and slash-and-burn agriculture. Early sub-Saharan African peoples followed Paleolithic lifeways, hunting with spears and bows and arrows (often tipped with poisons), and gathering wild plants such as fruits, nuts, melons, roots, and tubers. Even when some groups began to adopt agriculture (perhaps from as early as 8000 bce), others continued to practice hunting and gathering. Agriculture flourished in conducive regions, with sorghum, rice, peas, and nuts being cultivated in the Sudan from perhaps 4000 bce; grains, millets, sesame, and mustard in the Ethiopian highlands by 3000 bce; bananas (which were probably brought to Africa by Malays via Madagascar) and coffee in the jungles; and widespread successful domestication of livestock, including cattle, sheep, and goats.

Ironworking technology appeared in sub-Saharan East Africa as early as the seventh century bce and was rapidly diffused westwards to Nok (modern-day Nigeria). In the center of the period of most interest to our volume, so between c. 500 bce and c. 500 ce, Bantu peoples had spread south and east from their West African homelands to occupy and, to a certain extent, culturally and linguistically unify substantial regions of sub-Saharan Africa. By the year 900 ce, Africa was home to a diverse yet loosely unified array of complex cultures and states that were products of these earlier processes of cultural evolution and diffusion.

On the east coast, the region known as Ethiopia and Eritrea today was home to one of the continent’s longest and most enduring cultures. To the north, Nubians and Kushites had traded and fought with the ancient Egyptians thousands of years earlier; and by 800 bce, Arabian traders from Saba had begun to establish trading settlements along the Eritrean coast. The resultant Sabaean culture prospered through successful commerce. By the fourth century ce, the Ethiopian state of Aksum was dominating Red Sea trade, exporting exotic goods and slaves in exchange for glass, wine, and cloth, even issuing its own coins. Aksum’s King Ezana (r. 320–350) converted to Christianity, but three centuries later, in 615, Aksum gave refuge to a group of followers of the Prophet Muhammad, an act that heralded rapid Muslim expansion into East Africa. By the eighth century Islamic merchants dominated the coastal trade, but in the interior Christian groups continued to campaign against the coastal Muslims until as late as the sixteenth century.

Further south, the arrival of Bantu peoples along this stretch of the east coast had impacted the pace of historical change. The language that emerged (called Swahili after the Arabic word for coast, sawahil) gave its name to the entire coastal region. Although agriculturalists were successful, the region developed rapidly because of trade with merchants from the Mediterranean and the Arabian Peninsula. The early mariners’ handbook, the Periplus of the Erythrian Sea (c. 40/50 ce), lists several trading ports along the Swahili Coast, and through most of the first millennium Indian Ocean trade flourished, based on the export of ivory, rhinoceros horn, and turtle shells. The arrival of Islam intensified maritime trade, so that by the end of our period large commercial dhows were already navigating the deep waters of the Indian Ocean.

In West Africa, Berbers and agriculturalists of the Western Sudan and Niger Delta created wealthy states based on trade in gold, salt, and slaves. The Sahara was crisscrossed by a network of trading routes along which camel caravans transported these prized exports north to the Mediterranean coast. An initially small West African state known as Ghana (after its legendary warrior founder of the same name) commenced a period of sustained prosperity in c. 600 ce, and by the end of the ninth century Arabic sources were describing it as a powerful agricultural and commercial kingdom. The Ghanaian kings eventually consolidated their power by monopolizing the trade in gold and salt; and by the eleventh century ce the Ghanaian military possessed an army of perhaps 200,000 chain-mail-wearing soldiers.Footnote 24

The American world zone

The existence of Ghanaian soldiers and Byzantine emperors, of Muslim caliphs and Hindu gods, and of Chinese emperors and Australian aboriginals was completely unknown to small fishing communities that occupied the Western Atlantic island environment known as the Caribbean. Ciboney peoples from the South American mainland had slowly settled the islands during the second millennium bce, but by the end of the first millennium ce the more sophisticated Arawak culture had begun to displace them. These islands, and the vast continents of the nearby Americas, were so far isolated from events in Europe, Africa, and Asia by the broad Atlantic Ocean that they might as well have been on a different planet. Such had not always been the case, however. The ancestors of all the inhabitants of the Americas had originally come from Siberia and East Asia, crossing the Beringia land bridge that connected Russia and Alaska during the last ice age. The date of the arrival of the first humans in the Americas is uncertain, but by at least 15,000 years ago humans had begun to occupy a wide range of environmental niches the length and breadth of the American world zone.

Within a thousand years of the great migration to the Americas, the last ice age began to wane. As the glacial sheets melted into the oceans, sea levels rose to cover the land bridge, trapping and isolating humans and other fauna and flora on the American continents (although some migrations from East Asia probably continued by canoe). With the exception of a brief foray by Norse peoples to the east coast of North America in the ninth and tenth centuries, the Americas remained completely isolated from the other world zones until the arrival of the Italian navigator Columbus in 1492. By then, cultural evolution in the American continents had created a range of vibrant and successful societies, each well adapted to its particular natural environment.

Daybreak upon the east coast of the South American continent diffused a dappled sunrise through the dense vegetation of the Amazon River Basin rain-forest. Here, semi-nomadic tribal peoples were going about their business of hunting, gathering, and fishing in one of the planet’s richest biospheres. With no permanent records or architecture, historians can only conjecture about the lifeways of these people, although presumably little had changed by the arrival of the first Europeans around 1500 ce, who saw the natives as “noble savages” who nonetheless needed to be “civilized.”

Across the Amazon Basin on the west coast of South America, agriculture had been practiced in the coastal regions and mountain highlands of modern-day Peru since perhaps 8000 bce, and the gradual accumulation of surpluses had led to increased population densities and the creation of sedentary societies. The geography of the Central Andean region made communications challenging, which meant that it was more difficult for powerful rulers to establish unified state structures. Even so, by the early seventh century the Mochica culture was exerting a wide influence in northern Peru from its base in the Moche River Valley. The superb pottery of the Mochica offers us a glimpse at the everyday scenes that might have played out on any morning during that century. The ceramics depict everything from beggars on the streets to aristocrats hunting jaguar in the jungles, from women working in textile manufacturing to guards leading prisoners tied up with ropes. These images remind us that, although much has changed in the human condition in the centuries since c. 900 ce, many of the everyday experiences of humans have not.

In Central America to the north, humans had been farming since at least 4000 bce. The principal domesticates were maize, tomatoes, beans, turkeys, and dogs. Successful agriculture led to towns and early states, and by 1000 bce the Olmec people had constructed elaborate ceremonial and palace complexes, and divided themselves into a rigidly stratified society dominated by priests and elites. Soon after 400 bce Olmec culture declined rapidly, possibly as a result of significant environmental change. In the centuries that followed, a number of other cultures flourished at different locations across Mesoamerica. By c. 250 ce one of the most spectacular of these regional successors, the Maya, were firmly entrenched in city-states throughout modern Guatemala and parts of Mexico.

Mayan civilization reached its zenith during the seventh century ce. Through successful terraced agriculture, abundant maize and cacao harvests supported large populations, which gathered in dense concentrations at important ceremonial sites like Tikal and Chichen Itza. Particularly impressive was the bustling city of Tikal, which between 600 and 800 ce supported a population of perhaps 40,000. Mayan elite males were warriors, and conflict between city-states was ongoing. By the early ninth century, Maya society had fallen on hard times, a product perhaps of this endemic conflict, or environmental degradation, or both. The Maya religious myth, the Popol Vuh, claims that deities made humans out of maize and water, and that the gods would only keep the world going if they were propitiated by human sacrifice, with the blood of captured royal males and females of the enemy the most highly valued. Had any such ritual been played out toward the end of our volume’s “day,” sunset might have outlined the silhouettes of priests who had cut off the ends of the fingers of victims to ensure a copious flow of sacrificial blood.

In the highlands of Central Mexico, another complex Mesoamerican society flourished in the mid-first millennium ce, centered on the great city of Teotihuacan. Home to an astonishingly large population of perhaps 200,000 people by 600 ce, the inhabitants of Teotihuacan were responsible for constructing two of the most impressive monumental buildings in world architecture, the colossal pyramids of the sun and moon, which dominated the city skyline and remain just as impressive today as any of the monuments of Afro-Eurasia. Society in Teotihuacan was interconnected and stratified, with powerful rulers and priests, flourishing artisans, and perhaps two-thirds of the population engaged in farming. Before 500 ce there is little evidence of conflict in the region, but by the early seventh century Teotihuacan was under military pressure from surrounding peoples. Decline set in quickly, and in the eighth century Teotihuacan was sacked and burned.Footnote 25

Across the vast North American continent, a variety of political, cultural, and social traditions had emerged over the preceding millennia, so that by 1200 bce it was difficult to describe any single cultural model. Fishing and the gathering of marine resources remained the norm along the coasts, but inland hunting of large animals like deer and bison offered a sustainable lifeway. Both fishing and hunting peoples supplemented their diets by gathering berries, nuts, root vegetables, and wild grasses, but as is the case with hunter-gatherer lifeways everywhere, limited food resources and the necessity for mobility resulted in small and diffused populations. In a few select regions of North America, however, more complex societies and larger population densities did begin to appear, based on sedentary agricultural practices.

East of the Mississippi River Valley woodland communities practiced horticulture, cultivating maize and beans. Archaeologists are able to trace continuous cultural developments amongst the woodland peoples from around 1000 bce to 1000 ce, including evolving skills in woodworking, leatherworking, cultivation, shelter construction, and toolmaking. Sometime between 600 and 800 ce, the archaic spears of the Late Woodland Period were superseded by the bow and arrow, and semi-nomadic lifeways were replaced by permanent villages and dependence on farming, although the people never lost their skills of forest and large game herd management. The trend towards sedentism culminated in the emergence of large, state-like structures, including those of the Oscawa in 1000 ce, and the “nation” of the five Iroquois peoples (the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca) by c. 1400.Footnote 26

Forest dwelling tribes certainly knew how to use the naturally provided fruits of the woodland, but they also became skilled in manipulating the forests to their advantage. Archaeological evidence including charcoal deposits and pollen records, coupled with eyewitness accounts by early European settlers, has led to a revision of the view that the lifestyle of North American native peoples had little impact on the environment. It is now recognized that native peoples used fire extensively to clear land for planting corn, eliminating unwanted species like weeds while encouraging preferable species like blackberries and strawberries, and as a hunting technique. Grazing herds could be driven over cliffs by an accurate fire that took account of the prevailing winds, and many such “buffalo jumps” are known across North America. At the same time, fire could be used to keep grazing lands open and clear of other vegetation, which not only made hunting easier through enhanced visibility but also increased the size of herds. The notion that the native peoples of North America or Australia left no ecological footprint has now been replaced by a more realistic assessment of their environmental manipulation skills.

During the Woodland and later Mississippian eras, native peoples of eastern North America left their mark on the landscape in a different way, by erecting impressive earthen mounds. These structures are the largest examples of ancient monumental architecture in the Americas north of Mexico. Their function was varied. In some places the mounds took on the shape of an effigy of a culturally important animal, such as the Serpent Mound of Ohio. In other places the mounds served as burial structures, while others were platforms upon which ritual buildings or the dwellings of chiefs were erected. Construction of the most impressive mounds of all commenced at the very end of our era, at Cahokia near modern-day St. Louis. Between 900 and 1250 ce the Cahokia people constructed a complex of over a hundred large earthen mounds, and a sophisticated, interconnected society that astonished early European explorers.

Also late in the day for our volume, in the American Southwest Puebloan and Navajo peoples were practicing irrigation agriculture in their small fields of maize, beans, squash, and sunflowers. In the seventh century ce, the Puebloans began to construct surprisingly permanent solid stone and adobe structures. This process culminated in the construction of the great houses at Chaco Canyon, one of the most extraordinary archaeological sites in the world, which served as a major ceremonial, trade, and administration center for the region for four centuries between c. 850 and c. 1250 ce.Footnote 27

By c. 1200 bce native peoples on the west coast of modern Canada had been pursuing hunting, foraging, and fishing lifeways for at least 8,000 years. Archaeologists have discovered toolkits of macro and micro blades that were used to arm hafted spears and knives. Cultural diffusion across the plains of North America ensured that technological innovations (including pottery and the bow and arrow), as well as cosmological beliefs, spread widely. There is also some evidence that during the period covered by this volume, socially ranked hierarchies emerged in Canadian native societies, leading to increased warfare between communities.

To the frozen north of the Americas, finally, where Paleo-Eskimo fishermen and hunters would have enjoyed no warming sunlight on the first day of any of the 2,100 years between c. 1200 bce and c. 900 ce, because the Arctic regions were and are in perpetual night during the long northern winter. In the darkness these hardy people awoke in their icehouses to feed on frozen seal or fish, warmed by the fires they kept burning through the winter. They worked to maintain their fur clothing, their canoes, and other sophisticated hunting and fishing equipment (made of stone, bone, tusk, and antlers), which collectively allowed these human communities to survive and prosper in regions where few other members of their species could endure. Some skilled individuals might have spent the winter carving naturalistic designs into ivory and antlers, creating sacred objects to be used in the shamanistic religious practices common to so many hunter-gatherer peoples around the globe.

As the earth spun towards the completion of its cycle, in our case an extended day of more than two millennia, sunlight slipped back out across the Pacific to that imaginary “date line” which marks the division between the end of one day and the beginning of the next. Humans had been greeting the dawn somewhere on the planet for more than 70 million mornings before our symbolic daybreak, ever since Homo sapiens had first emerged in Africa more than 200,000 years earlier. Even as night now descended upon this extraordinary diversity of human lifeways and experiences, the intricate processes of history continued their inexorable progress toward the dawn of another day, and an increasingly complex future.

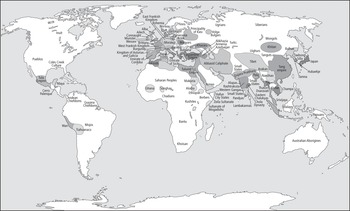

Map 1.1 The world in 1 ce

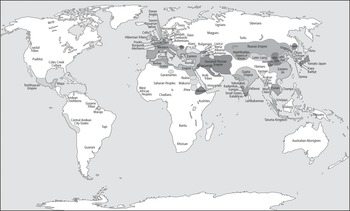

Map 1.2 The world in 400 ce