18.1 Introduction

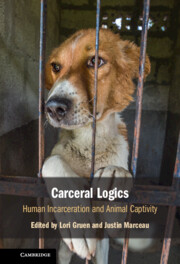

On April 27, 2014, the New York Times Magazine ran a cover depicting a chimpanzee in a witness box, wearing a blue suit, with a microphone and glass of water before him.Footnote 1 The well-dressed chimpanzee sat in a grand courtroom – dark wood, marble, an American flag – with a headline reading “His Day in Court.” The teaser reports that “A chimpanzee is making legal history by suing his captor – and raising profound questions about how we define personhood.” In terms of the burgeoning field of “animal law,” the iconography and messaging seem to be decidedly more about the law than about the animal.Footnote 2 In terms of media representations, the costuming and juxtaposition is more evocative of comedies featuring nonhuman apes doing “human things”Footnote 3 than of the few cinematic works that have endeavored to depict nonhuman apes as subjects, as members of communities, or as victims of human violence.Footnote 4

The accompanying article describes the efforts of the Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) and its founding president, Steven M. Wise, to achieve judicial recognition of animals as legal rights-holders. The juridical form of this advocacy is most often a habeas corpus claim brought on behalf of a particular animal.Footnote 5 The writ of habeas corpus, dating back to at least the early-thirteenth century, originally represented a bare “command…to have the defendant to an action brought physically before the court.”Footnote 6 In its contemporary role, the writ entails a command to “produce the body” of a detained individual so that the courts may review the legality of their detention.Footnote 7 Where a reviewing court finds that an individual is being deprived of their liberty without lawful authority, the writ of habeas corpus will issue, and the individual may be released.

The writ’s ancient pedigree and its association with bodily liberty have made it a legal tool with a complex relationship to carceral practices. The writ has functioned both to liberate illegally detained individuals and to affirm the validity of underlying systems of legally authorized incarceration.Footnote 8 The so-called Great Writ of LibertyFootnote 9 has thus survived and even thrived in a number of contexts where liberty interests have been systematically denied.Footnote 10 Advocacy surrounding the use of the writ on behalf of nonhuman animals in US courts has, however, tended toward aspirational, sometimes bordering on fantastical, accounts of the writ’s achievements in human justice contexts. These accounts rarely attend to the writ’s historical and contemporary role in sustaining rather than disrupting entrenched practices of human confinement, ranging from American racial slavery, mass incarceration, immigration detention, and the so-called war on terror. Instead, the writ, and the common law tradition more broadly, are portrayed by these advocates as manifesting a just and morally appropriate legal order that needs only to correct the “mistake” of omitting animals from its purview.Footnote 11

This chapter will introduce a corrective to this superlative vision of habeas corpus, its achievements in human justice contexts, and its potential for animal liberation. This study will begin by elaborating a critique of Wise and the NhRP’s approach to habeas corpus, arguing that this advocacy tradition overstates the writ’s accomplishments, often relying on an incomplete account of the writ’s history to do so. In particular, these accounts of the writ’s successes tend to paint struggles against racial violence and inequality as complete, thus minimizing the import of urgent ongoing justice projects. Next, a historical corrective is offered, demonstrating how closer attention to the writ’s actual role in human carceral systems can enrich our understanding of the writ’s limits and potential. This account will emphasize that the writ of habeas corpus operates only to challenge illegal (rather than unjust) detention; that it operates only at the margins of legal confinement systems to contain rather than to eliminate carceral practices; and that it therefore serves a role not only in challenging individual instances of confinement, but also in sustaining and validating ongoing carceral practices.

This more critical picture of habeas corpus, however, does not strip the writ of its potential as an advocacy tool for the interests of nonhuman animals. Instead, this chapter will argue, animal advocates might join other social justice movements in adopting a more ambivalent embrace of rights litigation. It is possible, often necessary, for advocates to turn to legal tools without adopting an uncritical posture toward law. Indeed, as with other ambivalent embraces of rights – including historical uses of habeas corpus – litigation is often a critical tool in bringing political attention to social injustices. In the case of habeas corpus litigation, this is best achieved through legal analyses that focus on the harms of confinement. Such efforts do not depend on a sanguine account of law. In fact, an excessive fealty to the underlying justice of carceral systems can thwart efforts to publicize their harms through litigation. Successful transformation of animals’ circumstances under law have almost always been driven by public attention to the suffering of animals at human hands. This chapter will propose that the greatest potential offered by the writ of habeas corpus is a focus on liberty that invites advocacy spotlighting the experiences of animals living within human systems of violence and confinement. It is this prospect of exposing and exploring the harms of human domination of other species – not any fantastical account of the writ’s human achievements – that gives habeas corpus its most meaningful transformative potential.

18.2 The “Great Writ”: From Fantasy to Reality

Wise’s discussions of habeas corpus vacillate between acknowledgment of the writ as a strategic or imperfect vehicle and description of the writ in lofty, idealistic terms. The focus of my criticism is on Wise’s more grandiloquent celebrations of the writ and the common law tradition more broadly. Wise’s honorific treatment of “the Great Writ”Footnote 12 is grounded in a similarly admiring approach to the common law tradition from which the writ emerged.Footnote 13 Wise describes the common law tradition as including an “objective” component that “thoroughly permeates Western law at every level and creates the near absolute barriers to the domination of one person by another that is the outstanding characteristic of western liberal democratic justice.”Footnote 14 This claim that law has created an effective bulwark against domination “seems to misstate the achievements of rights within human communities,” making sense only if we “look away from the facts and conditions of mass incarceration, immigration detention, police violence, and private violence indirectly supported by the state.”Footnote 15 This general mischaracterization of Anglo-American legal traditions is illustrated and made concrete in the context of Wise’s particular treatment of the writ of habeas corpus.

Wise’s description of the writ’s history is heavily focused on a general account of the writ’s development in the English medieval and Renaissance periods,Footnote 16 together with a discussion of the writ’s use in the context of American racial slavery.Footnote 17 Wise’s account of the writ’s emancipatory potential relies in significant part on his most developed case study, the 1772 case of Somerset v. Stewart, in which the writ of habeas corpus was successfully deployed to challenge the legality of the detention of an enslaved person.Footnote 18 In this historic decision, a British court found that slavery was contrary to the common law of England, and so refused to return an escaped, formerly enslaved person in England to a man claiming to be his “owner” under Virginia law.Footnote 19 The case is now widely regarded as establishing that slavery (which was not as widely practiced on English soil as in the AmericasFootnote 20) was illegal under English common law.Footnote 21

Wise’s treatment of this case tends to overstate both its practical achievements and its usefulness in illuminating the ordinary functioning of the writ of habeas corpus. Wise’s book examining this case is titled “Though the Heavens May Fall: The Landmark Trial that Led to the End of Human Slavery.”Footnote 22 The title “Though the Heavens May Fall” comes from the Latin maxim Fiat justicia, ruat coelumi (“Let justice be done, though the heavens may fall”), invoked by the presiding judge in the trial.Footnote 23 The subtitular reference to this as the trial that “led to the end of human slavery” exaggerates the role of this English decision in ending the American system of racialized chattel slavery, which drew to its formal close over one hundred years later,Footnote 24 within a different legal jurisdiction, and in the wake of economic transformation, a civil war, and the rebellion and advocacy of enslaved and formerly enslaved people themselves.Footnote 25 The titular reference to “the end of human slavery” erases the persistence of slavery as an economic and social practice around the world.Footnote 26 This description also obscures the fact that even within the United States, “involuntary servitude…as punishment for a crime” remains a legally permissible and highly raced carceral practice.Footnote 27

Wise describes the writ’s use in Somerset v. Stewart as “[p]aradigmatic,” suggesting that this was a typical example of the writ’s operation.Footnote 28 In fact, this was quite an exceptional case.Footnote 29 The availability of habeas corpus and other legal mechanisms for reviewing the legality of the detention of enslaved people generally posed little or no disruption to the institutions of American racial slavery.Footnote 30 The court’s conclusion that Somerset could not lawfully be held as a slave depended on a finding that his common law liberty rights had not been displaced by statute: “The state of slavery is of such a nature, that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political; but only by positive law… : it’s so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law.”Footnote 31 In other words, if English legislation had authorized Somerset’s enslavement, the writ would not have issued. Even within England, the Somerset judgment was confined to the individual case before the court, and was not followed by a “rush for writs” on behalf of other enslaved people within England.Footnote 32 The impact of the decision was even slighter within American states, where slavery was authorized and regulated by statute. As legal historian Paul Halliday has observed in connection with this case, “[h]abeas corpus, by its nature, could not enable a judge to declare illegal an entire system of bondage created by colonial legislatures.”Footnote 33 The writ of habeas corpus is available to review the legality of detention; insofar as slavery or other kinds of detention were lawful, the writ posed no threat to associated systems of confinement. The availability of the writ of habeas corpus is entirely consistent with ongoing, systemic, legalized confinement.

Exaggeration of the writ’s role in bringing slavery to an “end” is part of a broader, damaging rhetorical strategy that has often been deployed by animal advocates. Analytic links (implicit and explicit) between contemporary animal use and American racial slavery have been pervasive in the animal advocacy movement,Footnote 34 despite persistent objections. Animal advocates have been criticized for taking an interest in chattel slavery not to attend to its complexity and ongoing impacts, but with the aim of “pronouncing it dead and naming animal slavery as its successor.”Footnote 35 As Angela Harris has observed, these analogies often depend on an “implicit assumption that the African American struggle for rights is over, and that it was successful” – an implication that is both inaccurate and potentially harmful to the ongoing justice struggles of Black Americans.Footnote 36 Claire Jean Kim elaborates that such an approach “relentlessly displaces the issue of black oppression, deflecting attention from the specificity of the slave’s status then and mystifying the question of the Black person’s status now.”Footnote 37

The retelling of the human history of habeas corpus as one of triumph – especially triumph over legalized forms of race-based violence and confinement in the United States – is both misleading and dangerous. Black Americans continue to experience disproportionate levels of state violence, including through policing, surveillance, and mass incarceration.Footnote 38 The availability of habeas corpus has not dismantled these systems, nor has it eliminated their disparate impacts along racial lines. Habeas corpus – the Great Writ of Liberty – thus continues to operate within racially ordered carceral systems that confine and kill human beings. The writ has not been a wrecking ball of justice, boldly demolishing systems of confinement, “though the heavens may fall.”Footnote 39 Instead, the writ has served as a more modest legal tool – one that has curbed the excesses of those carceral practices that are illegal even within systems that generally authorize violence and detention.

18.3 Rethinking Habeas Corpus and Its Limits

Habeas corpus is best understood as operating to contain specific carceral practices at the margins while also working to authorize or confirm the legal legitimacy of carceral systems as a whole. The writ functions only to stop or restrain detentions that are unlawful, meaning that the underlying legal order must disapprove of the carceral practice in order for the writ to work as a restraint on that practice. Moreover, the writ serves as an effective check only where one part of government is thought to be disobeying the law, and the judiciary can be expected to intervene to correct this disobedience. Habeas corpus is not a legal mechanism for dismantling systems of confinement – it is a mechanism for holding those systems of confinement to their own rules. Its effectiveness depends on the strength of underlying substantive rights (i.e., legal limits on detention) and on institutional considerations (i.e., whether reviewing courts are likely to safeguard those limits more effectively than other legal decision-makers). This characterization of the writ is supported by two well-studied contexts of US habeas corpus litigation: federal judicial oversight of state criminal procedure and judicial review of executive detentions at Guantánamo Bay.

Consider, first, the role that the writ of habeas corpus has played in facilitating the oversight of state criminal procedure by federal courts. During the 1960s, the Supreme Court of the United States substantially increased the application of federal constitutional protections to state criminal process, including prohibiting the use of evidence obtained through illegal searchesFootnote 40 and requiring that accused persons be advised of their rights in interrogation.Footnote 41 State courts adjudicating criminal proceedings, however, were often hostile and resistant to the introduction of these federal constitutional requirements.Footnote 42 The writ of habeas corpus came to play a critical role in subjecting state criminal convictions to review before federal courts, assuring the protection of federal constitutional protections in the face of state court recalcitrance.Footnote 43 Historians and legal scholars have debated the extent to which this represented a major expansion of habeas corpus or simply a modest continuation of the writ’s historic office.Footnote 44 In either case, it is undisputed that any waxing in the availability of habeas corpus certainly waned in subsequent years of legislative and judicial restrictions on the writ’s availability.Footnote 45 Nonetheless, the writ continues to play a role in assuring the legality of detention in state criminal proceedings through review by federal courts.

The availability of habeas corpus as a mechanism for bringing constitutional violations before federal courts is, of course, deeply significant to individual defendants and incarcerated persons who would have otherwise had little meaningful hope for protecting their rights.Footnote 46 However, if we hope to understand the role of habeas review within the broader context of criminal carceral practice, another reality becomes equally important: that the availability of habeas corpus in individual cases has not worked to end or reduce the scale of state carceral systems. Instead, rates of incarceration have ballooned since habeas review of state courts’ compliance with federal constitutional requirements was affirmed.Footnote 47 Moreover, in all cases, the writ’s function remains the supervision of the legality of the particular detention under review, rather than the underlying justice of criminal carceral systems more broadly.

Perhaps the most striking and intuitive example of the split between habeas review (focused on legality) and interrogation of the underlying justice of detention is the Supreme Court of the United States’ judgment in Herrera v. Collins.Footnote 48 In that case, the Court effectively established that actual innocence of the crime for which a person has been convicted is insufficient as a basis for postconviction relief: “federal habeas courts sit to ensure that individuals are not imprisoned in violation of the Constitution – not to correct errors of fact.”Footnote 49 Habeas corpus was thus found to offer a veneer of judicial oversight, expressly foreclosing attention to the justice or injustice of the underlying carceral system.Footnote 50 Because of the writ’s focus on legality and procedural oversight, the enforcement of rights through habeas corpus proceedings has played a role not only in challenging specific instances of illegality, but also in confirming and legitimizing underlying carceral systems.Footnote 51

We can observe similar limits on the transformative potential of habeas corpus in the writ’s application to persons detained at the Guantánamo Bay detention camp. In a series of cases before the Supreme Court of the United States, advocates successfully argued that the writ must be formally available to those detained at the camp,Footnote 52 and that statutes limiting access to the federal courts to adjudicate such habeas claims amount to an unconstitutional suspension of the writ.Footnote 53 The imperative to achieve meaningful access to the writ derived largely from these advocates’ assumptions that federal judges would recognize and apply the legal rights of detainees more effectively than the military commissions established to adjudicate these cases.Footnote 54 In practice, however, the appellate court to which most of these cases flowed turned out to be remarkably resistant to these habeas claims, even where they had been successful before lower courts.Footnote 55 Notably, the Supreme Court’s affirmation of the availability of habeas review respecting detentions at Guantánamo Bay left open the essential question of which legal rules might actually constrain executive authority to detain in these cases. A recent federal court judgment answered this question with a remarkably restrained account of the substantive legal rights that might apply in these cases. The court held that the Due Process Clause of the federal constitution’s Fifth Amendment could not be invoked by “an alien detained outside the sovereign territory of the United States,” effectively limiting constraints on detention at Guantánamo Bay to those created by statute.Footnote 56 Limited to these minimal statutory protections, prosecutors are permitted, for example, to rely on evidence obtained from another detainee through torture or coercion.Footnote 57

It is difficult to pin down the precise impact of this habeas litigation on the carceral project at Guantánamo Bay. The total number of detainees at Guantánamo Bay has dropped significantly as a result of policy choices by the Obama administration. It is at least arguable that years of habeas litigation played a role in keeping the spotlight of public opinion on the plight of Guantánamo Bay prisoners, provoking this policy shift. There may be, moreover, some symbolic significance to the Court’s extension of the writ to Guantánamo Bay detainees, emphasizing in the public psyche the principle that the demands of justice must extend even to the most detested prisoners, and even to a space seemed designed to operate outside the confines of law. In terms of direct legal effect, however, the Supreme Court’s confirmation that the writ of habeas corpus may be used to challenge detentions at Guantánamo Bay has had starkly limited consequences. The limited scope of legal rights constraining detentions has meant that prisoners have not actually been released as a result of judicial pronouncements in habeas corpus proceedings. In fact, the D.C. Circuit Court has sided with the executive in every single case where it has challenged a habeas claim asserted by a person detained at Guantánamo Bay.Footnote 58 The D.C. Circuit Court’s caselaw in these matters underlines the reality that the writ’s effectiveness in challenging detentions will always depend on both institutional realities (here, respecting whether the judiciary might serve as a check on executive power) and on the definition of underlying substantive rights. In the case of Guantánamo Bay, a finding that few substantive rights constrain government authority has gutted the practical impact of habeas corpus review: individual prisoners are simply not being set free on judge’s orders pursuant to the writ. Moreover, despite the decrease in the number of prisoners held at Guantánamo Bay, the writ’s availability has not ended the basic underlying carceral system in issue. The detention center remains open and legally authorized, holding prisoners who are unprotected by federal constitutional rights.Footnote 59

The writ, then, has not proven itself to be an effective device for reliably dismantling systems of legalized confinement. As a legal tool, it is best understood as a procedural mechanism designed to ferret out instances of illegal detention within systems that, more broadly, continue to authorize carceral practices. The significance of the writ derives not from its capacity to unearth new substantive protections, but from its particular function within systems where some part of the government is disobeying or overstepping the established confines of its legal authority. It is for this reason that the writ is so strongly associated not only with the “liberty” of individuals but also with structural features of the American legal system. In the Guantánamo Bay cases, the relevant structural feature is “‘separation of powers,” balancing the roles of executive, judicial, and legislative authority.Footnote 60 In cases respecting federal courts’ oversight of state courts, the relevant structural feature is “federalism,” balancing the roles of state and federal governments.Footnote 61 The writ of habeas corpus serves to restrain illegal confinement, allowing one part of government to supervise the legality of another authority’s particular actions within contexts of legalized violence and incarceration. The writ operates within, and lends legitimacy to, the broader carceral systems and logics of which it forms a part, even as it works to invalidate some individual instances of confinement. In short, the writ is better described as confining carceral systems to “business as usual” than to mandating transformation “though the heavens may fall.”Footnote 62

18.4 Special Challenges for Habeas Corpus Claims on Behalf of Animals

This understanding of habeas corpus – as a tool within, rather than a threat to, carceral systems – is of particular significance in the animal protection context. On what basis might we claim that it is not only wrong but unlawful to confine an animal? In the case of federal court supervision of state criminal procedure, the limits of lawful detention are defined by federal constitutional rights. In the case of Guantánamo Bay prisoners, it is breach of statutory protections that might render detention unlawful. In the case of Somerset v. Stewart, it was the common law that was held to prohibit the detention in issue, a protection that the court explicitly noted would extend only as long as no positive law permitted slavery in England.

A hard reality for animal advocates is that most practices of contemporary animal confinement are clearly authorized – and often affirmatively encouraged or practically required – by legislation and regulation.Footnote 63 This statutory context poses special challenges for habeas corpus claims on behalf of animals. The presence of statutes governing the conditions in which animals may be confined stands to frustrate claims rooted in the common law. Wise and the NhRP have been clear that it is not their intention to seek enforcement of animal protection legislation; they instead assert that there is an underlying illegality to animal confinement (at least in some cases) that is defined by common law principles.Footnote 64 Given the thicket of statutory law governing animal captivity,Footnote 65 it is difficult to imagine a court accepting an argument of this kind, even if they were to find the writ to be available in respect of animals. Recall that even in Somerset, the court acknowledged that positive law could authorize slavery in England even if the common law prohibited it.Footnote 66 Consequently, even if the NhRP were to succeed in arguing that the common law included liberty rights for animals, it would be an additional hurdle to prove that animal confinement is the sort of unregulated space in which a meaningful common law claim might grow unencumbered by statutory interventions.Footnote 67

One approach to these statutes might be to incorporate them into habeas claims: to argue that the detention of some animals is unlawful precisely because these animals are held in contravention of animal protection legislation.Footnote 68 There is long-standing debate and contradictory jurisprudence respecting whether human prisoners may use the writ of habeas corpus to challenge conditions of confinement as opposed to the fact of confinement itself. At the federal level, the Supreme Court of the United States has left open the possibility that habeas corpus may be available to challenge conditions of confinement,Footnote 69 and circuit courts are presently split on the question.Footnote 70 In New York State, where the NhRP has brought its habeas corpus claims, the case law has generally rejected the application of the writ to challenge conditions of confinement, but has allowed that such claims may succeed where a prisoner seeks to be removed to “an institution separate and different in nature” from the correctional setting specified by their sentence.Footnote 71 As the NhRP has argued, seeking a chimpanzee or elephant’s removal to a sanctuary might fall within this ambit.Footnote 72 This certainly seems more plausibleFootnote 73 than the claim that an underlying common law liberty right for animals has survived the thorough legislative and regulatory codification of animal captivity.

The NhRP, however, has spurned the route of advancing claims that animal detentions are unlawful due to contraventions of statutes and regulations.Footnote 74 To be sure, the thin legal protections that are afforded to animals respecting their autonomy and bodily integrity (i.e., animal “welfare” laws)Footnote 75 are often woefully underenforced.Footnote 76 Access to the writ of habeas corpus to cure these defaults would represent a victory for animals, especially considering the obstacles animal advocates have faced in arguing that they have standing to compel agency enforcement action.Footnote 77 Nonetheless, the NhRP has chosen the more difficult path of grounding their claims in common law liberty rights. This decision is likely informed by the organization’s commitment to an “animal rights” philosophy,Footnote 78 pursuant to which animals (at least great apes, elephants, dolphins and whales) should have legally protected rights to “bodily liberty” and “bodily integrity.”Footnote 79

A legal order that respected animals’ rights to bodily liberty or bodily integrity would not allow the routine injury, capture, or killing of animals – all practices that are currently commonplace and legally authorized. Recognition of such animal rights would require revolutionary transformations in our practical relationships with other animals, notwithstanding Wise’s insistence that it would be an incremental change within the logic and jurisprudence of the common law.Footnote 80 But, as we have seen, habeas corpus is not a revolutionary tool. The writ, instead, provides remedies for individual cases of confinement that fall outside of the legally sanctioned norms of entrenched carceral systems. The NhRP’s litigation briefs take this individualistic form, emphasizing in each case that the court need not – must not – consider the policy implications of animal liberation.Footnote 81 Instead, the NhRP urges, each case concerns only the one animal before the court.Footnote 82 In the case of Happy the elephant, the NhRP argues, the court must consider only Happy, not the other (metaphorical) elephant in the room: if Happy may not be legally detained, what does this mean for a sociolegal order that has long treated the injury, captivity, and death of animals to be routine, even foundational?Footnote 83

It is perhaps this tension between revolutionary ambitions and the limits of quotidian legal tools that has contributed to Wise’s overly celebratory accounts of the common law and the writ of habeas corpus. Suggestions that the writ requires justice be done “though the heavens may fall”Footnote 84 may be thought to give hope for the claims of animals despite significant doctrinal obstacles and entrenched practices of legalized animal confinement. But, as we have seen, such lavish praise for the “Great Writ” and its achievements is both misleading and harmful. In reality, the writ has served comfortably within and alongside systems of confinement, curbing only those marginal practices that are unlawful within the terms of those systems themselves. To suggest otherwise minimizes or erases the ongoing realities of state-sanctioned violence and carcerality.

18.5 Habeas Corpus and the Critique of Rights: The Ambivalent Embrace of Legal Tools

Other justice movements have struggled with this tension between their own revolutionary ambitions and the conservative nature of legal tools. Social justice advocates have often found it necessary to rely on legal languages and logics, even while acknowledging their limits. Legal tools can be, and have been, picked up by advocates who maintain a critical posture toward the systems with which they engage. As Mari Matsuda explains in describing the use of rights strategies in human and civil rights contexts:

[I]t would be absurd to reject the use of an elitist legal system or the use of the concept of rights when such use is necessary to meet the immediate needs of [a] client. There are times to stand outside the courtroom door and say, ‘This procedure is a farce, the legal system is corrupt, justice will never prevail in this land as long as privilege rules in the courtroom.” There are times to stand inside the courtroom and say, “This is a nation of laws, laws recognizing fundamental values of rights, equality and personhood.” Sometimes, as Angela Davis did, there is a need to make both speeches in one day.Footnote 85

It is possible to appeal to entrenched legal tools and values while keeping in view the reality that these tools and values may be elements of unjust carceral orders. The choice to resort to habeas corpus advocacy does not require animal advocates to claim that the writ has ended injustice wherever it has applied, or that urgent, ongoing justice struggles are complete or resolved.

The embrace of rights litigation by feminist and critical race theorists offers a model for a more ambivalent relationship to legal tools. As telegraphed in Matsuda’s quotation above, the language of “rights” has long been criticized by feminist and critical race theorists, who nonetheless conclude that rights can be an important device for advancing substantive justice projects.Footnote 86 These scholars have largely accepted a body of arguments referred to collectively as “the critique of rights.”Footnote 87 One element of this critique is that rights are less transformative than many people assume, and may in fact play a critical role in sustaining existing hierarchies and power relationships.Footnote 88 Another element of this critique is that rights language is “mystifying,” obscuring how law functions in practice, and directing an inordinate focus on individual cases at the expense of structural dynamics.Footnote 89 These critiques – of mystification, individual rather than systemic focus, and participation in sustaining the status quo – are echoed in the preceding critique of grandiose habeas rhetoric. Yet, despite general agreement that legal rights advocacy has these shortcomings, feminist and critical race theorists have largely settled on an uneasy embrace of rights-based litigation strategies.Footnote 90 The ambivalent embrace of rights is grounded in strategic imperatives that hold true for habeas corpus advocacy as well.

First, rights are critical sites of power and contest within existing legal systems.Footnote 91 This is also true of habeas corpus, a procedural mechanism with deep roots in the Anglo-American legal system, and which has served as a focal point for social and legal battles ranging from racial slavery to civil rights to the “war on terror,” as we have already seen.Footnote 92 Second, rights carry distinctive social and legal force as a means of expressing need, constraining power, or, at the very least, demanding official response.Footnote 93 This, too, is a feature of habeas corpus advocacy. At a minimum, claims brought in habeas corpus on behalf of animals have required those holding animals captive to offer legal justifications, and have required courts to offer reasons for their conclusions as to why these justifications are legally sufficient.Footnote 94

Those pursuing habeas corpus claims on behalf of animals may benefit from the writ’s deep roots in American legal thought and practice, and its capacity for demanding official response, without advancing grand, misleading claims about the writ’s achievements for human beings and the law’s “objective” tendency to end domination.Footnote 95 In fact, once we strip away Wise’s sanguine account of the writ’s achievements in human justice contexts, the writ offers a different kind of promise for animal advocates.

18.6 Habeas Corpus and the Harms of Captivity

Habeas corpus claims offer more than an entrée into existing American legal praxis, capable of forcing engagement with the claims of animals. The writ also invites substantive engagement with some of the most grievous harms facing animals: harms of captivity.Footnote 96 Animals are so routinely caged, and this caging so widely understood as harmful, that the idiom “like a caged animal” has become a central metaphor for the pains of liberty deprived.Footnote 97 To the extent that the harms of confinement, and the corollary value of liberty, are core justice concerns of animals, habeas corpus presents a particularly apt legal framework for elaborating claims. Wise and the NhRP are correct in identifying the writ of habeas corpus as being intimately connected to “liberty” as a legal value both historically and in contemporary practice.Footnote 98 The demands of “liberty” are, however, famously contested in human justice contexts.Footnote 99 The strongest forms of habeas corpus advocacy are those that recognize that the common law, and the writ of habeas corpus, do not represent an inexorable march toward a predefined and objective liberty, but rather a partial and fraught inroad into debates about carceral practices and the value of autonomy.

Wise’s view of habeas corpus as part of an inherently just common law order, grounded in part in “objective” principles,Footnote 100 has at times manifested in advocacy strategies that attend to supposedly objective facts about animals. The attendant evidentiary focus is on the intrinsic qualities of animals, rather than on the subjective and relational experiences of animal lives in captivity. Such lines of argumentation seek to prove, for example, that nonhuman great apes have legally relevant “autonomy” because they are logical, able to use tools, are self-aware, or have the capacity for language.Footnote 101 In response, scholars have charged that Wise and the NhRP focus excessively on arguments that animals are “like” people on a series of measurable metrics.Footnote 102 This focus on animals’ similarities to humans has been criticized for replicating underlying logics of domination and hierarchy and for wrongly accepting the premise that “facts about difference…explain why powerful groups exploit and harm less powerful groups.”Footnote 103

Significantly, this strategy is not a capitulation to some clear, existing legal standard. There is no accepted judicial or statutory framework for assessing which entities are eligible for habeas corpus under the relevant statuteFootnote 104 or who counts as a rights-bearing legal “person” more generally.Footnote 105 Instead, Wise and the NhRP have chosen to foreground this scientistic approach, echoing the supposed objectivity that Wise has attributed to just common law reasoning.Footnote 106 Habeas advocacy might just as easily pursue a different track. Instead of seeking to prove as a matter of “science” or “logic” that animals fall into the category of rights-holders, advocates might seek to prove as a matter of relationship and recognition that animals live, love, and hurt in ways that should matter to law.Footnote 107 Rather than focusing on animals’ ability to meet sterile scientific tests of capacity (mirror self-recognition, for example), habeas corpus advocacy might focus instead on what animals value in their own lives.

I have proposed a simple standard for assessing whether an animal ought to qualify as a holder of rights in habeas corpus: whether the animal in question has a substantial interest in their own liberty.Footnote 108 Rather than focus on an animal’s provable skills or talents, this inquiry directs us to consider the animal’s subjective experience: “Does this animal feel the burdens of captivity? Does this animal yearn to be free?”Footnote 109 If so, their confinement gives rise to “the underlying harm at which habeas corpus aims: that the burdens of captivity should not be imposed without lawful cause.”Footnote 110 Juridically speaking, this standard does not resolve all of the challenges that habeas corpus actions on behalf of animals face. The significant obstacles to proving animal confinement unlawful remain. But the threshold inquiry to which we are directed is reshaped. Instead of a prodding assessment of the animal’s intrinsic qualities, the analysis would begin with an exploration of the harms of confinement.

Scientific evidence may still play a role in evaluating habeas corpus claims on this standard, but the focus would be on what research reveals respecting the value of freedom to animals, for example in their lives as friends, as mothers, and as kin.Footnote 111 Rather than arguing that chimpanzees, for example, ought to have access to habeas corpus because they are objectively “like us,” it might be argued that chimpanzees value their own relational autonomy,Footnote 112 that they suffer in isolation or when their kinship bonds are broken, and that law can and should serve as a vehicle for those interests. Under such an approach, ethological evidence respecting how chimpanzees form relationships, care for their young, grieve their dead – and how these relationships are frustrated by confinement – tells us more about the validity of claims for chimpanzees’ liberty than facts about, for example, whether chimpanzees can learn to use sign language in a laboratory.Footnote 113

Elements of this proposed approach already exist in the NhRP’s filings. Their petition on behalf of Happy the elephant, for example, explains that “elephants are a social species who suffer immensely when confined in small spaces and deprived of social contact with other members of their species,” citing expert evidence that elephants held in isolation experience boredom, depression, and other emotional and physical harm.Footnote 114 The petition further notes that elephants recognize and respond to the voices of their family members,Footnote 115 and that separation from their families in human captivity causes trauma so severe that their cognitive capacities are impaired for years following the separation.Footnote 116 The framework within which this evidence is advanced, however, does not emphasize the harms of captivity. Instead, the NhRP marshals this evidence to prove that Happy “possesses complex cognitive abilities” that should qualify her for liberty rights – appearing alongside detailed evidence of elephant brain size, complexity of communication patterns, and memory.Footnote 117 This focus on proving Happy’s intrinsic qualities – that she is like humans in her skills and capacitiesFootnote 118 – comes at the expense of an inquiry into her experience of captivity. Pages of submissions are dedicated to proving these “abilities,”Footnote 119 while a single paragraph attends to the fact that “elephants are a social species who suffer immensely when confined in small spaces and deprived of social contact with other members of their species.”Footnote 120 This is not for want of evidence on the point.Footnote 121 In addition to the well-documented “social and psychological deprivation, physical deterioration, suffering and premature death” suffered by captive elephants, experts report that captivity leaves elephants “unable to fully engage in the seminal activities that define individual identities, relationships and cultural experiences – activities that may be among the most important components of elephants’ lives, providing purpose, depth and meaning.”Footnote 122

A legal standard focused on animals’ experiences of their own liberty and its deprivation would reverse this emphasis, calling attention not to animals’ abstract capacities, but to their values, relationships, and experiences – including the realities and details of their suffering in captivity. The underlying portrait of law need not be one of an intrinsically fair system, embodied in a Great Writ that will aid liberty in any just case. Instead, the legal order may be accepted as a complex field of power and persuasion, littered with battles that have been hard-fought and half-won. Instead of proceeding as though logic and objective proof are the driving force of habeas argumentation, it is possible to proceed as though the writ’s availability should be anchored in the tedium, frustration, and sorrow of life in a cage.

18.7 Representing Animal Law: Beyond A Chimp in a Suit

Courts are not the only audience for habeas corpus litigation. Halliday sums up his historical survey of the writ’s use in England and its colonial empire by noting that the “idea of habeas corpus” has often been “more powerful outside of courtrooms than inside them.”Footnote 123 He reports that advocates – including Somerset’s lawyer, Granville Sharp – were “often disappointed in the liberating ambitions they pursued at law,” but that, crucially, “[i]n cases like theirs…the idea of habeas corpus has continued to influence public debate.”Footnote 124

Wise and the NhRP have not limited their battles to the courtroom. Litigation stands as just one pillar of their three-pronged mission, alongside legislative advocacy and a broad “education” mandate.Footnote 125 The NhRP’s petitions must be assessed in this context: as part of a broader strategy for transforming the legal status of animals.Footnote 126 Whatever difficulties we may identify in their strategies and tactics, it is undeniable that the NhRP has been wildly successful in attracting media attention to their cause.Footnote 127 Might the shortcomings of the NhRP’s framings be justified by the public attention they have drawn to the claims of captive animals?

I have argued elsewhere that the law reform efforts that have most effectively achieved transformation for animals have been those that have illuminated and publicized the particular facts of animal experience in compelling emotional appeals.Footnote 128 Wise’s emphasis on the significance of the writ can lead to media stories that feature the grandeur of law: the Greatness of the Great Writ, or the weight and meaning of “personhood” as a legal status. This focus draws attention to animals as a legal curiosity – a chimp in a suit – rather than animals as victims of violence and confinement. The media coverage often emphasizes the law rather than the animal.Footnote 129 As the New York Times Magazine cover suggests,Footnote 130 the media image projected may focus on the oddity of an ape in a courtroom rather than on the tragedy of an ape in a cage.

Habeas corpus advocacy, however, need not advance a triumphalist vision of law. Strategies that emphasize the harms of captivity, rather than the supposed greatness of legal traditions, have greater potential to persuade courts and publics that animals need and deserve legal protection. Litigation focused on animals’ own lives, values, and relationships might dovetail with public education and advocacy approaches that recognize the value of animal experiences on their own terms – not as near-humans, but as beings whose experiences matter in their own right.Footnote 131 The NhRP’s legal strategy has invited the image of an awkwardly styled chimpanzee in a suit – a misfit in a system designed with others in mind. Habeas corpus claims grounded in a threshold concern with the harms of captivity might instead invite images of animals as mothers, brothers, or friends – beings whose realities our legal system should strive to recognize.