Book contents

- Carthage in Virgil’s Aeneid

- Cambridge Classical Studies

- Carthage in Virgil’s Aeneid

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations, Editions and Translations

- Introduction: Tractatio, Re-tractatio, Revisionist History

- Chapter 1 Carthaginian Constructions, since the Middle Republic

- Chapter 2 Polarity and Analogy in Virgil’s Carthage

- Chapter 3 Virgil’s Revisionist Epic and Livy’s Revisionist History

- Chapter 4 Virgil’s Punic/Civil Wars as Unspeakable

- Conclusion: All the Perfumes of Arabia

- Bibliography

- General Index

- Index Locorum

- References

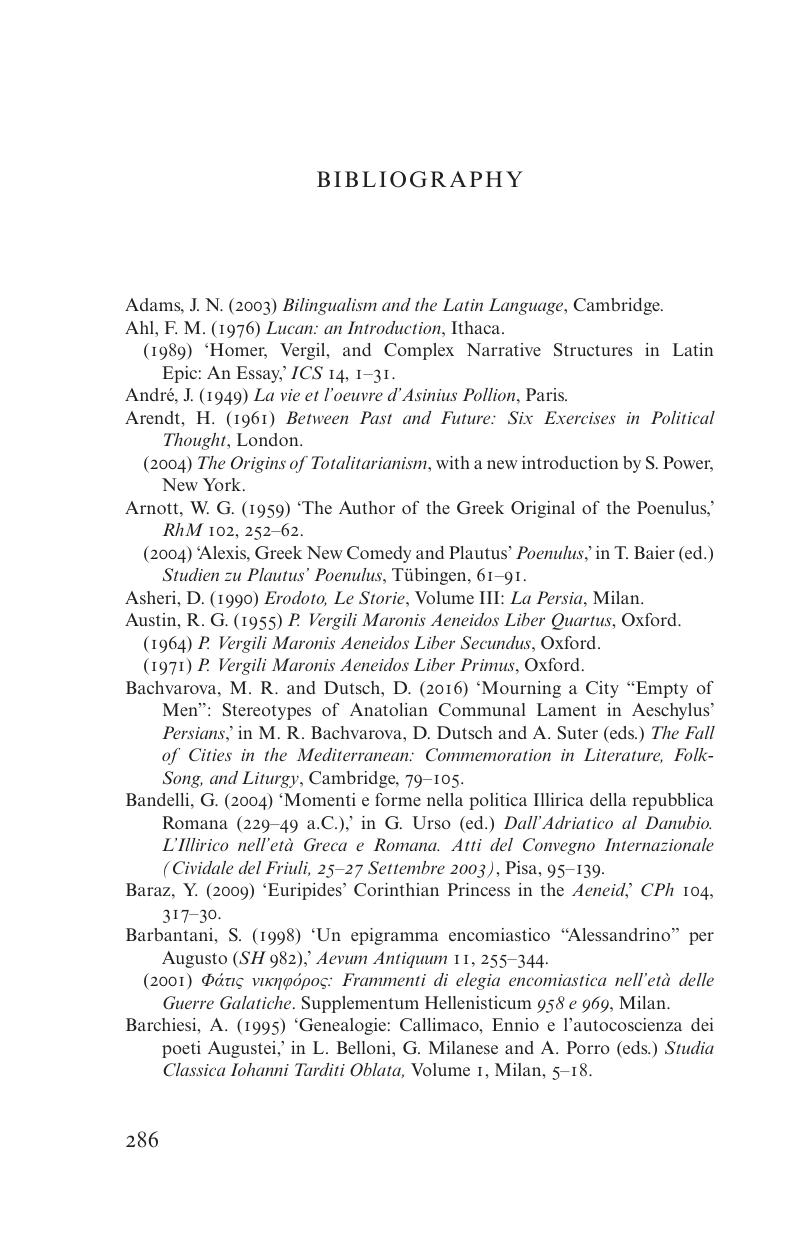

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 March 2018

- Carthage in Virgil’s Aeneid

- Cambridge Classical Studies

- Carthage in Virgil’s Aeneid

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations, Editions and Translations

- Introduction: Tractatio, Re-tractatio, Revisionist History

- Chapter 1 Carthaginian Constructions, since the Middle Republic

- Chapter 2 Polarity and Analogy in Virgil’s Carthage

- Chapter 3 Virgil’s Revisionist Epic and Livy’s Revisionist History

- Chapter 4 Virgil’s Punic/Civil Wars as Unspeakable

- Conclusion: All the Perfumes of Arabia

- Bibliography

- General Index

- Index Locorum

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Carthage in Virgil's AeneidStaging the Enemy under Augustus, pp. 286 - 311Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2018