1 Overview

The case study examines the construction of the Imperial Pacific casino in Saipan, a US commonwealth in the Western Pacific, by Chinese firms employing Chinese workers. The focus is on the serious labor abuses that transpired and the legal and other consequences faced by the companies as a result. The case sheds light on the structure and operations of these Chinese construction projects, including the layers of contracting and subcontracting. It also explores how efforts to maximize speed and minimize costs resulted in numerous violations of local laws and the severe economic and reputational costs that this had for the companies. In addition, the case examines what actions the abused Chinese workers on such projects may take to enforce their rights and address their mistreatment. The case study therefore provides a useful tool to consider the issues involved in hiring and supervising contractors, such as cost, contract provisions, subcontracting, monitoring, and liability. The case also provides a platform to explore what legal, advocacy, and other tools workers and their advocates can use when legal violations and labor abuses occur. Additionally, this case study provides a uniquely detailed account of the events that transpired in Saipan because the author served as a lawyer representing the abused workers in a lawsuit alleging that they were subjected to forced labor. As a result, the case study draws upon court filings from that litigation, as well as construction contracts and subcontracting agreements, documents from local law enforcement agencies, criminal complaints, media reports, and worker interviews.

2 Introduction

In October 2022, seven Chinese construction workers reported that they recovered more than US$6.9 million through a lawsuit against the Imperial Pacific International (IPI) casino in Saipan, part of the US Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) in the Western Pacific, and the two Chinese contractors who employed them to build the casino, subsidiaries of the Chinese firms Metallurgical Corporation of China (MCC) and Suzhou Gold Mantis (Gold Mantis). The result came after nearly four years of litigation over events that had occurred six years prior. In or around 2016, while in China, the workers had been promised construction jobs in “America” with reasonable hours, high pay, room and board, and good conditions, and therefore paid high recruitment fees for this opportunity to work in Saipan. Instead, upon arrival, they had their passports confiscated, discovered they lacked work visas, worked long hours with no rest days, were not paid, were subjected to verbal threats and physical violence, and faced a worksite less safe than anything they had experienced in China. Each of these seven men also suffered a physical injury on the site, such as a scorched leg, burnt hand, or severed finger. The workers were part of a group of nearly 100 workers who had been directly supervised by Kong Xianghu, an individual with a few registered limited-liability companies, but were provided Gold Mantis T-shirts and hard hats and worked alongside other Gold Mantis workers. A few had also previously been employed by a supervisor working for MCC. The workers lived in dormitories provided by IPI. Between all the various Chinese contractors on the project, there were more than 2,400 Chinese workers with experiences just like those of the seven plaintiffs.

This case study explores the construction of the IPI casino in Saipan by its Chinese contractors, tracing it from the inception of the project until the conclusion of the worker lawsuit. In doing so, the case provides a platform for exploring numerous issues concerning overseas construction projects being carried out by Chinese firms, including relations with local governments; contracting and subcontracting arrangements; compliance with local law; and the criminal, economic, and reputational consequences of noncompliance. The study also provides a window into examining what legal, advocacy, and other tools workers and their advocates can use when legal violations and labor abuses occur.

The case study therefore proceeds in seven sections: the first introduces the political and economic context in Saipan and how the IPI project came about; the second focuses on the structure of the contractor and subcontractor relationships on the project; the third describes IPI’s manpower shortage and the illegal recruitment methods used to solve it; the fourth discusses the various labor abuses perpetrated by IPI and its contractors toward the Chinese construction workers; the fifth reports on the various government and private enforcement efforts to remedy these labor abuses, such as criminal punishment, orders to compensate workers, fines, and a forced labor lawsuit; the sixth discusses how the workers themselves and other civil society actors helped to achieve a remedy for the workers; and the seventh explores the broader ramifications of this case on the companies, the CNMI, and US-China relations more generally.

The author served as the lawyer representing the seven workers in their forced labor suit against IPI, MCC, and Gold Mantis. The case study draws upon many of the court filings from that litigation and also the actual construction contracts and subcontracting agreements, documents from local law enforcement agencies, criminal complaints, media reports, and worker interviews.

3 The Case

3.1 Background on Saipan and IPI

The CNMI is a series of islands in the Pacific Ocean, of which the largest and most populated island is Saipan. After World War II, the CNMI was part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands administered by the United States but later formed a political union with the United States in 1976. At that time, there were no quotas or tariffs on goods shipped from the CNMI to the United States. The CNMI also largely retained control over its immigration system and set its own minimum wage. This combination proved very attractive to apparel manufacturers, who could bring in foreign laborers from various parts of Asia, pay them very little, and export the goods to the US market. This allowed for the development of a garment industry that exported US$1 billion in goods each year and employed tens of thousands of factory workers.

However, after the media exposed the horrible labor abuses engaged in by garment employers in the late 1990s, a series of class action lawsuits brought down the industry. In 2009, pursuant to the Consolidated Natural Resources Act of 2008, Congress ‘federalized’ control over immigration to Saipan, stripping the local government of much of this power.Footnote 1 A 2007 law created a schedule for raising the minimum wage in the CNMI to match the federal level by 2018.Footnote 2 The US Department of Labor (USDOL) also established a permanent presence on the island. The intention was that such federal oversight over who enters and leaves Saipan, as well as over employers’ compliance with federal minimum wage and other laws, would ensure that the abuses experienced in the garment industry would not repeat themselves in Saipan.

Despite these reforms, the CNMI still received special treatment from the federal government in other respects, however. In order to encourage tourism to the islands, a program was created in 2009 that permitted Chinese tourists to be paroled into the CNMI for up to forty-five days without needing to obtain a visa.Footnote 3 Between 2013 and 2016, the number of Chinese tourists to CNMI each year grew from 112,570 to 206,538.Footnote 4 Around the time that immigration was federalized, Congress also created the CNMI-Only Transitional Worker program (or “CW-1” program) in response to the CNMI’s claimed need for foreign workers. While other programs for unskilled guest workers already existed, such as the H-2A and H-2B programs, the CW-1 program allowed workers from a broader list of industries and home countries (such as China) to be legally employed in the CNMI. When first established, the CW-1 program provided a decreasing number of permits each year, as the intention was for this program to be gradually phased out.Footnote 5

After the garment industry more or less dissolved in the mid 2000s, the CNMI never found an economic driver to replace it.Footnote 6 But, around 2014, this changed – or so people thought. During this time, the Chinese government was imposing tighter restrictions on the casinos operating in Macau, the only place in China where gambling is legal. It had become increasingly difficult for wealthy Chinese to get their money to Macau, and many of the junket operators and casinos there were losing money or even closing operations. In this context, one of these Macau junket operators approached a group of Saipan government officials about opening a casino on the island.Footnote 7

On 12 August 2014, the CNMI government executed a Casino License Agreement (CLA) that provided IPI the exclusive right to operate a casino with table games in Saipan. The license was for twenty-five years, but IPI then had the option to extend for an additional fifteen years. In exchange, IPI was obligated to invest a minimum of US$2 billion, construct 2,000 new hotel rooms of at least a four-star quality, and pay an annual license fee of US$15 million.Footnote 8 The CLA also provided that IPI would seek to have 65% of its workforce comprised of US permanent residents, as opposed to foreign guest workers, and IPI agreed to provide the CNMI Department of Labor (CNMI DOL) with quarterly updates on its progress toward meeting this goal.

IPI is the entity that was registered in the CNMI to operate the casino hotel. But IPI is a wholly owned subsidiary of Imperial Pacific International Holdings (IPIH), a holding company registered in the British Virgin Islands and with offices in Hong Kong. IPIH has been listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange since February 2002.Footnote 9 The largest shareholder of IPIH was mainland Chinese businesswoman Cui Lijie, although many viewed the project as really driven by her son, Ji Xiaobo. Cui had been listed by Forbes magazine as one of Hong Kong’s fifty richest people in 2017.Footnote 10

3.2 Construction of the Casino Project

On 15 January 2015, IPIH executed an “EPC general contract” (EPC总承包合同) appointing MCC International Engineering Co., Ltd. (MCC International) as the general contractor on the casino resort project in Saipan. MCC International is registered in Hong Kong and is a subsidiary of the Metallurgical Corporation of China, a central state-owned enterprise (SOE) mining conglomerate headquartered in Beijing. MCC International then created its own subsidiary in Saipan, MCC International Saipan Ltd. Co. (MCC Saipan), to operate the casino project.

In December 2015, a “General Construction Contract” (施工总承包合同) was then executed between MCC Saipan and IPI to implement the agreement between the parent companies. (In the course of the forced labor litigation, IPI made public both the original Chinese version of this contract and an English translation.) The first pages of the contract identify the parties and the initial contract price of US$200 million. The remainder of the roughly seventy-six-page contract appears to be a standard form, primarily comprised of boilerplate provisions but including very few details specific to the project. Most of the appendices, which are supposed to be tailored to the project, are left blank. The contract basically puts all obligations for compliance onto MCC. For instance, MCC was obliged to comply with all applicable laws, ensure safety on the site, be responsible for the actions of its subcontractors, hire employees locally, and generally be responsible for complying with all labor laws, including those regarding workers’ pay, housing, meals, and transportation.

IPI also engaged numerous other contractors for the project. Although often described as subcontractors of MCC, many of these companies were contracted by IPI directly, not by MCC. For instance, the Suzhou-based construction and design firm Gold Mantis (金螳螂), which is traded on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, was hired to work on the casino hotel. The firm Nanjing Beilida (倍立达) (Beilida), a privately owned company, was also engaged by IPI. In fact, at least four other Chinese companies, including large firms like Sino Great Wall International Engineering and the Jiangsu Provincial Construction Group, also had contracts related to construction of the casino project.

The contracts between IPI and its contractors took a variety of forms. In contrast to the seventy-six-page contract with MCC, the agreement with Gold Mantis, executed in December 2016, is an eight-page English document with only eighteen sections.Footnote 11 Interestingly, while Gold Mantis is referred to as the “Contractor,” IPI is called the “Employer/Owner.” Nonetheless, the contract provides that Gold Mantis is responsible for the “labor works” of certain classes of workers, but not those subcontractors directly appointed by IPI. IPI was obligated to assist in applying for manager and worker visas as well as dealing with the government policy or legal problems, while Gold Mantis was made responsible for providing sufficient manpower and performing the contract “in accordance with all applicable laws and regulations.” The contract set a provisional price of US$6 million and provided that a “cost plus pricing mechanism” will be used, which means that the contractor essentially submits invoices and the developer pays an amount equal to those invoices plus some agreed-upon percentage of that amount as the contractor’s profit. It is important to consider what incentives such a pricing structure creates for the contractor.

These contractors often further subcontracted out their work on the casino project. For instance, Gold Mantis worked with an individual, Kong Xianghu, to manage a group of nearly 100 construction workers. Kong operated under at least three different corporate entities. With one of the entities, Gold Mantis executed a two-page contract to provide it with “labor services” on the IPI project for an agreed-upon fee schedule that was not listed in the contract. It stated that “no labor relationship is established” between the parties, and that Kong’s entity is “responsible for all safety accidents of its workers.” MCC, too, engaged in some similar arrangements, whereby it would engage an individual who was in charge of a group of workers and then make periodic payments to that individual. Beilida, too, had individuals who were in charge of a group of workers, and these individuals would receive a lump sum payment from the company based on the labor performed by their workers, which they were then responsible for distributing to the workers. As discussed further in Section 3.3, a critical issue is the extent to which these “subcontractors” were or were not independent of IPI and the Chinese construction firms.

3.3 Recruitment of Workers

Pursuant to the CLA, IPI was required to open the casino resort by January 2017. From the outset, IPI projected that it would need 2,000 workers to complete construction. (The population of the CNMI was just over 47,000 in 2020, which is a 12.2% decrease from 2010.)Footnote 12 There is also a CNMI regulation that requires 30% of any company’s workforce to be US permanent residents, as opposed to foreign workers.Footnote 13 However, in January 2016, the CNMI DOL said there were only about 1,000 construction workers in the CNMI, meaning there was an obvious labor shortage. Generally, in order to get US permanent residents from outside the CNMI to come work in Saipan, the employer is required to pay their travel and housing costs as well as a significant wage that is high enough to make this work attractive. Thus, finding US workers to satisfy IPI’s need for labor would have been extremely costly.

Instead, IPI petitioned the CNMI DOL to grant an exemption to the 30% rule for its various Chinese contractors. Documents obtained from that agency show that the CNMI DOL approved IPI’s subcontractors to bring in more than 6,000 foreign workers. (These foreign workers were still required to have proper authorization to work in the CNMI.) However, getting these workers was not so easy. Whereas the cap on CW-1 workers had never been reached before 2016, all 12,999 CW-1 permits for 2016 had already been issued less than halfway through that year.Footnote 14 This was primarily due to the IPI project: for instance, whereas only 1,231 CW-1 workers came from China in 2015, more than 5,000 came from China in both 2016 and 2017.Footnote 15 IPI fought to meet its deadline with the workers it had by having them perform construction late into the night and even on Sunday, despite regulations forbidding this practice. Nonetheless, IPI later announced it would need to push back the opening. But IPI still needed more workers to avoid pushing it back even farther.

In order to resolve this manpower shortage, IPI, MCC, and the other contractors then began to bring in workers from China who lacked any work visas. The workers would be paroled into the CNMI as “tourists” but then immediately start working on the construction site. Many of these workers were actually defrauded in China, where recruiters told them that they were going to “America”; that they did not need a visa (or sometimes that one would be provided); and that they would only work six days per week, eight hours per day, and earn a large salary paid regularly. In exchange, the recruiters charged workers a recruitment fee, often around US$6,000 – more than the average annual wage of a Chinese construction worker – and sometimes far more. These “tourist workers” then often worked alongside the other construction workers who had proper visas, sometimes under the same supervisor, and living in the same dormitories.

Later on, when this illegal scheme was uncovered, IPI would claim that this plan to bring in these “tourist workers” – often referred to as “heigong” (黑工) – was entirely done by the contractors. The contractors, like MCC and Gold Mantis, argued that they also had hired subcontractors who brought in and supervised these tourist workers. However, evidence later revealed that executives and managers at IPI, MCC, and the other contractors were not only aware of what was happening but actively involved in developing and executing the plan.Footnote 16

3.4 Labor Abuses

In the effort to get this project done quickly and cheaply, IPI and its contractors engaged in a series of practices that violated CNMI and federal laws. Some of these practices seem to be clear imports from how construction sites are run in China, such as paying a daily wage rate, but other policies were not simply what employers were used to doing at home – like confiscating worker passports. In this particular instance, there is much evidence that these companies were not ignorant of the different laws in the CNMI and United States. Instead, they knew the law but nonetheless chose not to comply.

There are numerous illustrations of the contractors’ commitment to reducing costs. Documents show that MCC had actually calculated the money that would be saved by hiring Chinese workers and paying a below-minimum wage salary instead of hiring US workers and paying a legal wage. The fact that MCC and other contractors brought in the Chinese workers as tourists rather than go through the expensive and cumbersome process of properly obtaining visas for workers is another example of violating the law to save costs.

The contractors also implemented a management style that included many forced labor-like conditions in an effort to maximize worker productivity and minimize cost. The contractors made workers labor for seven days per week for twelve or more hours per day. The overtime was mandatory. They did not pay workers on time but were always in arrears, meaning a worker could not quit without forfeiting his prior unpaid earnings. The daily wage that the companies promised to pay also violated rules on the minimum wage and overtime. Managers confiscated workers’ passports, also making it hard for them to quit, and overtly threatened that if they complained or quit they would be deported to China without receiving their pay. Workers were also housed in a rat-infested dormitory that even lacked a certificate of occupancy. These conditions were remarkably similar across all IPI’s many contractors.

IPI, MCC, and the contractors also refused to take proper safety measures. Workers received little or no training and often lacked the proper protective equipment. The fatigue from working so many hours with no rest days also made workers susceptible to getting injured. Indeed, many workers described the condition as worse than anything they had seen in China. An affidavit submitted in court revealed that emergency room doctors at the local hospital documented eighty serious injuries on the casino site just in the year 2016, prompting them to contact the relevant federal agency, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), about the dangerous nature of the worksite. The doctors also reported cases where they recommended that a patient be hospitalized and not transported, like a worker with a broken back, but the Chinese employers sent him back to China nonetheless. The contractor generally did not permit any of the tourist workers to receive medical treatment because they feared it might expose the fact that they were employing undocumented workers.

After performing its inspection in 2016 and 2017, OSHA eventually found twenty-four violations by MCC, Gold Mantis, and Beilida.Footnote 17 The citations were for hazards related to inadequate fall protection, unsecured scaffolding, unprotected crane operation areas, and unguarded machines. And, in March 2017, one tourist worker died after falling 24 feet from the casino’s scaffolding and breaking his neck.Footnote 18 Rather than report all these injuries to OSHA as required by law, IPI and its contractors instead tried to cover them up. It is this incident that prompted the FBI to intervene by raiding the offices of MCC, Beilida, and others, and arresting some of the managers.

3.5 Government and Private Enforcement

The cost-cutting decisions resulted in some serious consequences imposed by various US federal government agencies. First, the FBI and US Department of Justice criminally prosecuted Zhao Yuqing, the MCC project manager, and Qi Xiufang and Guo Wencai, two subcontractors/supervisors for Beilida, for knowingly employing and harboring undocumented workers, resulting in at least three individuals spending time in jail. Court documents show that agents discovered passports of undocumented workers in a drawer at MCC’s office and a list of “visa” and “illegal” workers at Beilida’s office. Another indictment was later issued against an IPI executive and another MCC manager who coordinated for workers to enter as tourists and devised ways to deceive immigration officials.

The USDOL also investigated the nonpayment and underpayments to the workers. This resulted in MCC, Beilida, and other contractors paying more than US$13.9 million to 2,400 workers, including about US$6,000 per person to reimburse the recruitment fees that were paid in China. Although these companies all claimed that they were not actually the ones recruiting the workers in China or collecting those fees, the USDOL found it proper that they be responsible for repaying them. Even IPI, since it too exercised some control over the workforce, was sued by USDOL and eventually agreed to pay US$3.3 million toward compensating the workers.Footnote 19

As for the health and safety violations, public records show that OSHA’s inspection of the site in 2016 that found twenty-four safety violations resulted in fines levied against MCC, Gold Mantis, and Beilida in the combined amount of US$193,750.Footnote 20

In addition to this government enforcement, workers also sued IPI and its contractors in the federal court located in the CNMI. In the most noteworthy case, seven Chinese workers filed a complaint in early 2019 alleging that IPI, MCC, and Gold Mantis subjected them to forced labor, which also resulted in the physical injuries they suffered on the construction site. Under the federal Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act, not only a recruiter or employer but any individual or entity that “knowingly benefited” from the forced labor may be liable to the victims. After the judge found the workers had a plausible claim, MCC and Gold Mantis paid to settle with the seven workers. IPI continued to fight but refused to hand over the WeChat messages, emails, and other evidence requested by the workers, resulting in the court entering a default judgment against the company and setting damages at US$5.9 million. After roughly eighteen months, the workers were then able to collect the full amount of the judgment from the casino.

In each of these proceedings, IPI initially sought to put all the blame for the unpaid wages, unsafe conditions, confiscation of passports, and dismal living conditions onto its contractors, and would point to the language in their agreements making the contractors responsible for all such labor issues. Similarly, the contractors sought to put the blame on their subcontractors, such as individuals like Kong Xianghu, claiming that they were unaware of what those subcontractors were doing. However, the facts failed to support their arguments. IPI had arranged for the workers to live in the same crowded, rat-infested dormitories that lacked a certificate of occupancy, and transported them from the dorms to the worksite each day. IPI’s general counsel also denied entry to an OSHA inspector when he first arrived at the construction site. As for the contractors, the workers allegedly employed by the different “subcontractors” often lived in the same dorms, rode the same buses, wore the same company uniforms, and were overseen by the managers. Thus, even if the abused workers were technically supervised by a subcontractor to some degree, these facts made it possible to hold IPI and its contractors liable for the abuses that they suffered.

3.6 Worker and Civil Society Efforts

The Chinese workers themselves also took actions against IPI and its contractors to remedy the abuses they suffered. Some of these efforts worked in conjunction with government enforcement efforts to pressure IPI and its contractors to pay compensation, while others were independent of those efforts.

After the FBI raids in March 2017, many of the company managers fled from Saipan, and the Chinese workers were left stranded and unpaid. Despite previously being terrified to speak out due to their lack of visas and fear of employer retaliation, the workers now began demonstrating in the streets of Saipan demanding that they be compensated for the work that they performed. The workers also insisted that they would not return to China, as both the companies and some government agencies were encouraging them to do, until they had been paid. Not only did the local newspapers and TV stations cover the story but so did major international outlets, like the New York Times, which named the contractors and how each one had previously touted their participation in this project as contributing to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The workers also wrote a public letter to the Chinese Consulate in Los Angeles (which has jurisdiction over Saipan) discussing how they were abused by these Chinese companies and wanted help.

The workers’ efforts and the international media coverage then prompted other civil society organizations to get involved. Groups like the National Guestworker Alliance and Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions made statements calling on IPI and its contractors to pay the workers. China Change released videos profiling the situation, including by documenting the company’s efforts to assuage the protesting workers by buying them cigarettes as well as showing the workers who had been injured on the site but received no treatment and no compensation. The videos also called on people to write to the Chinese contractors insisting that the workers be paid. Adding to the reputational costs for the companies, the IPI project was named one of the “Most Controversial Projects of 2017.” The labor abuses at the site would become a topic at US congressional hearings on the state of Saipan.Footnote 21

The demonstrations by the workers, their insistence on being paid before returning home, and then the attention from the media and civil society put pressure on IPI and its contractors to resolve the issue. (It also likely put some pressure on the USDOL to ensure that the workers were fairly compensated and to ensure that the money was actually paid.) In addition to the contractors’ own interest in preserving their reputation, there have been suggestions that the Chinese government also leaned on the contractors to pay the workers and resolve the case, as it was negatively impacting China’s image. In particular, much of the media coverage about the incident noted that the Chinese contractors described their work in Saipan as part of the BRI. Since this is a signature policy of Xi Jinping, allegations of labor abuses on such a project are particularly sensitive for the Chinese government. Accordingly, it is plausible that the government may have pressured the Chinese contractors to resolve the matter and end the stream of negative attention.

Many of these same dynamics were at play after the lawsuit alleging forced labor was filed against IPI, MCC, and Gold Mantis. Numerous international media outlets reported on the case. The litigation was referenced at a US congressional hearing on forced labor perpetrated by Chinese companies. Advocacy efforts were also directed at the investment community and various financial regulators. For instance, Amnesty International argued publicly that IPI’s parent company and an MCC subsidiary were not in compliance with the environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure rules of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange on which they were listed. Both MCC and Gold Mantis, unlike IPI, eventually agreed to settle the claims against them in the forced labor suit. This negative attention, along with raising red flags for investors and regulators, may have contributed to the desire of these companies to settle by compensating the workers.

3.7 Aftermath

After the FBI raids, IPI continued its work on the casino-hotel project. It initially hired a contractor that employed US workers, who ended up claiming it was owed money and sued IPI. IPI then hired workers from other countries under the H-2B guest worker program, until USDOL eventually debarred IPI from the program, thus revoking its ability to do so; this forced IPI to rely again on contractors who would bring in the workers. IPI was able to finish construction of the casino and opened it in July 2017; however, to this day, the hotel portion remains unfinished.

The events that transpired on the IPI project had significant implications beyond just that project. Starting in October 2019, the parole program for Chinese tourists was revised so that individuals could only remain in CNMI for fourteen days rather than the forty days previously permitted.Footnote 22 Sources suggest that this was driven in large part by the way IPI and its contractors exploited the parole program to bring in workers.

In July 2018, Congress also made changes to the CW program under which many of those construction workers who had visas were working. Although the overall program was extended – it was originally scheduled to phase out in 2018 but was instead extended to phase out in 2030 – no future permits were to be granted to construction workers unless they qualified as long-term workers. Employers would also be required to demonstrate that there were no willing and able US workers in the CNMI before bringing in a CW-1 worker.Footnote 23 In addition, employers found to have engaged in human trafficking or serious labor abuses would be barred from the program, which also was largely a result of the abuses on the IPI project.

In short, the massive abuses by IPI, MCC, and Gold Mantis significantly impacted the future of the CNMI’s relationship with China, both by making it harder for Chinese tourists to visit and by making it harder for Chinese workers to get permits to be employed on Saipan. It seems logical that this may also lead to a slowing of Chinese investment into the island.

4 Conclusion

The story of the IPI casino in Saipan provides a detailed illustration of an overseas Chinese construction project. The case highlights how some firms sought to resolve their need for manpower, deliver fast construction, and minimize costs by adopting practices that largely violated federal and local immigration laws, safety rules, wage and hour laws, trafficking and forced labor laws, and other labor rights protections. However, such practices are not unique to Saipan; instead, they are commonly employed by Chinese firms on projects across the globe.Footnote 24 The Saipan case illustrates how failing to adapt these practices to comply with local laws may have extremely high costs to the companies involved as well as the broader relationship between China and that locality.

5 Discussion Questions and Comments

The case of the IPI casino in Saipan identifies several critical issues that arise with large construction and infrastructure projects involving Chinese firms. This section discusses those issues and raises questions that should be considered by all stakeholders, including policymakers in the host country, executives and managers at the construction firms, and worker advocates.

5.1 For Law and Business School Audiences

5.1.1 Subcontracting Arrangements: When and How to Use Them, as Well as Legal Risks and Their Mitigation

An extremely common component of these Chinese construction projects is the extensive use of multiple levels of subcontracting.Footnote 25 In Saipan, the developer hired MCC as a general contractor, then engaged other contractors such as Gold Mantis and Beilida, and each of them contracted with supervisors as well as recruiters in China. While there is a business logic to this practice, it is often employed by developers and larger contractors to avoid liability for the labor or other violations taking place. Yet, in Saipan, despite contractual language assigning responsibility to the subcontractors, IPI, MCC, and other larger contractors were still held liable for the recruitment, labor, and safety abuses.

The case therefore offers an important lesson to companies about the importance of carefully considering the structure of their subcontracting arrangements. If not managed properly, this may create serious economic and reputational damage to developers and contractors. As a starting point, companies must make themselves familiar with the relevant legal framework. Companies then must decide whether to engage subcontractors or to handle various functions themselves. In what circumstances should companies use or avoid subcontracting arrangements? If subcontractors are hired, how will such arrangements be structured? What mechanisms will be adopted to allow the company to monitor the subcontractors and ensure their compliance with the law? Or will the company take a “hands-off” approach, risking that abuses may occur and intending to then feign ignorance if they are uncovered?

5.2 For Law, Business, and Policy School Audiences

5.2.1 Finding Redress for Labor Exploitation, Including Legal and Extra-Legal Strategies

Even the most careful planning or detailed set of regulatory measures cannot entirely eliminate the risk of noncompliance and abuse. Therefore, it is critical to consider what legal or other avenues are available to raise and remediate grievances. Many Chinese overseas projects lack a well-developed channel for workers (or other stakeholders) to raise complaints about wages, safety, or other conditions. However, when such mechanisms do not exist, or do not resolve the problem, workers and their advocates need to find other means to exert pressure on employers to remedy abuses. The Saipan case offers some important lessons on how this can be achieved. The workers (and then civil society groups) were able to exert pressure on the Chinese companies to remedy the abuses they suffered through a combination of public demonstrations, engaging the media, and appealing to the Chinese government. Some workers successfully used the local legal system to obtain compensation for being subjected to forced labor and for the physical injuries that were never adequately addressed by the construction firms. However, this was only possible due to legal rules that permitted undocumented workers to access the courts, lawyers to charge a contingency fee (i.e., only receive payment if money is collected for the client), and plaintiffs to participate in the legal process even after returning to China. Of course, the ability of media to operate freely and the rules of civil litigation may vary greatly by jurisdiction. Therefore, it is crucial that policymakers consider creating an environment that permits workers to seek redress, and advocates must evaluate how to best navigate that environment in each case. Thinking broadly, when labor exploitation occurs, what avenues are available to raise and remediate grievances? What legal and extra-legal strategies are available to workers and their advocates?

5.3 For Business School Audiences

5.3.1 Managing the Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Foreign Workers

For many large-scale construction or infrastructure projects, particularly in more remote regions, the local population may lack the manpower or skills to perform the job. However, importing a large number of foreign workers also creates risks and challenges. The migrant workers themselves are often extremely vulnerable to severe exploitation. Like in the Saipan case, the workers are transported far away from their homes to an unfamiliar place where they do not speak the language, do not know the law, and are entirely dependent on their employer. If they do not have a proper visa or legal status, their vulnerability is further heightened. So, what are the advantages and risks of using foreign workers? How should the use of foreign workers be managed? What measures should be put in place to minimize the risk of such labor abuses? The influx of foreign workers may also have a significant impact on the host country that must be considered. What will be the effect on the community or environment of this sudden growth in the population, particularly in a place with limited resources? Will the use of foreign workers create resentment among unemployed or underemployed local residents? Serious consideration must be given to these questions before a plan to bring in foreign workers is set in motion.

1 Overview

Gold mines in Kyrgyzstan that are owned and operated by Chinese investors have experienced several problems in recent years, chief among them being labor disputes with local workers. These disputes mark a pattern of dysfunction in one of Kyrgyzstan’s most critical industries. They are further significant for a number of additional reasons. First, they shine a light on the realities of doing business in a controversial sector in a developing country. Second, they demonstrate labor issues from the host state side, specifically the difficulties of finding decent work for Kyrgyz laborers, and how certain industries may thereby engage in predatory practices. Third, they show the ineffectiveness of government intervention. This case study will expose readers to the causes of the problem and encourage them to critically assess the responses of various stakeholders to the disputes. It also will assess the extent to which different fields and concepts of governance are either well-established in corporate practice and across industries, a function of supranational governance, or are Chinese-inspired innovations apply to Kyrgyzstan’s gold mining sector. These range from corporate social responsibility (CSR) and environmental, social and governance (ESG) to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the “Green Silk Road.”

2 Introduction

2.1 History and Significance

Following independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Kyrgyzstan’s gold mines were initially seen as an opportunity for foreign investors and local actors to work together to develop the country. Since then, however, the gold mining industry has struggled to fulfill its potential and, in general, the view of foreign investors has soured. This is best illustrated in the well-documented case of the Kumtor gold mine, which was once owned and operated by Canadian firms. Located in the east of the country, Kumtor is Kyrgyzstan’s largest mine. It accounted for 68% of national gold output in 2022 and is arguably the country’s single most significant productive asset.Footnote 1 Although a report on Kumtor’s contribution to economic growth is no longer available on the mine operator’s website, it was reported by commentaries in 2021 and 2022 as accounting for 12% of Kyrgyz GDP and 23% of Kyrgyz industrial output.Footnote 2 However, since the start of its operations in 1997, the Kumtor mine has also become the object of scrutiny and criticism because of its river pollution,Footnote 3 damage to glaciers,Footnote 4 and tax irregularities,Footnote 5 as well as corruption scandals that have implicated former Kyrgyz presidents.Footnote 6 In 2022, the Kyrgyz authorities unilaterally seized control of the Kumtor mine.Footnote 7 This then prompted bankruptcy litigation and international arbitration in the United States, Canada, and Sweden, which culminated in an out-of-court settlement marking the end of Canadian control.Footnote 8 Overall, the scandals have tarnished the image of foreign direct investment in Kyrgyzstan, which is now closely associated with corruption, environmental damage, and socioeconomic inequality.Footnote 9 However, such scandals have not been exclusive to Kumtor and have grown to pervade a swathe of Kyrgyz gold mines – irrespective of the nationality of the foreign investor. A number of such mines are now operated and owned by Chinese firms. In the region covered by this case study, Jalal-Abad, eighteen out of twenty-eight gold mines are owned by either a Chinese individual or an organization.Footnote 10

This case study focuses on labor conflicts between Chinese investors and local Kyrgyz workers in the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat gold mines. These are both located in Jalal-Abad, which is a mountainous borderland in the west of Kyrgyzstan. Compared to the Kumtor mine, these mines are smaller in scale and output and, therefore, do not have the same economic significance as Kumtor. But focusing on labor disputes in the context of such mines is important as doing so provides a bottom-up view of the potentially adverse social and environmental impact of Chinese investments in the extractives sector. To date, although such investments have not led to the same public fallout as the Canadian-owned Kumtor mine, they are becoming the subject of scrutiny for two reasons. First, CSR and ESG initiatives and responses related to the UN SDGs are being increasingly applied to and adopted by the extractives industry as a whole. Second, this topic provides a lens through which to consider the role of Chinese businesses as a “responsible player” on the global stage and their mandate to shape their investment activities as a means of promulgating a “Green Silk Road.”Footnote 11

2.2 Case Study Roadmap

This case study focuses on the “lifespan” of a typical labor dispute between local Kyrgyz workers and Chinese companies, using the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat gold mines as examples. Attention is paid to the socioeconomic and legal origins of such a dispute, especially to factors arising prior to and during employment. In addition, it addresses how local and national governments as well as Chinese companies respond to labor strikes and the chosen methods of dispute resolution (e.g., formal litigation or informal settlement). In particular, the case study discusses the Chinese company’s mass dismissal of 400 Kyrgyz workers in order to avoid bankruptcy at the Ishtamberdy mine. Laborers there had engaged in long-term disruptive strikes against substandard working conditions and the nontransparent hiring of workers through intermediary organizations. In addition, the case study will also explore the environmental criticisms from local stakeholders that have heightened concerns about worker protests at the Kichi-Chaarat mine, leading management to increase security in and around the facility. Finally, the case study will explain the relevance to the disputes of such factors as corporate culture, labor division, and the promotion and education opportunities for Kyrgyz workers. Hence, this case study will reveal the complexity of local and national conditions encountered by Chinese mine managers and owners in Kyrgyzstan. It will show not just how Chinese investors have responded to these local conditions but also how stakeholders on the Kyrgyz side have reacted, demonstrating how multiple parties contribute to outcomes.

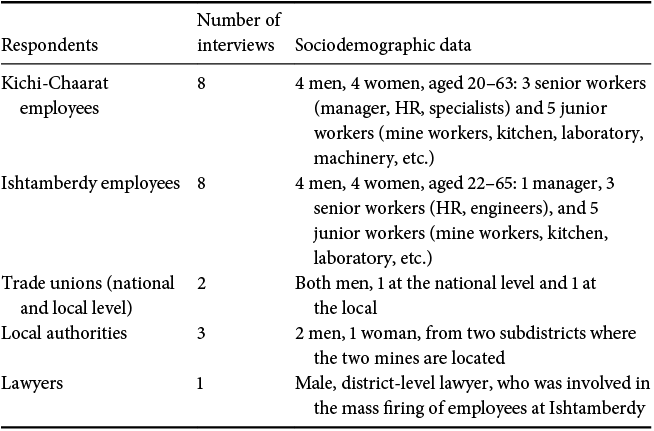

This case study is primarily based on twenty-two in-depth interviews held in November and December 2022 with employees and managers at the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat gold mines, as well as with local authorities and representatives of mining trade unions (see Table 4.2.1). The employees of the gold mines were sampled according to age, gender, seniority, management responsibility, and current job status (i.e., whether they are still employed or whether their employment has terminated). Given the general absence of any transparent reporting culture and the sensitivity of critiquing the mining sector, these in-depth interviews were crucial in helping to understand the issue. Some respondents were reluctant to answer and the percentage of refusals to participate in the study was high.

Table 4.2.1 Information on interview respondents

| Respondents | Number of interviews | Sociodemographic data |

|---|---|---|

| Kichi-Chaarat employees | 8 | 4 men, 4 women, aged 20–63: 3 senior workers (manager, HR, specialists) and 5 junior workers (mine workers, kitchen, laboratory, machinery, etc.) |

| Ishtamberdy employees | 8 | 4 men, 4 women, aged 22–65: 1 manager, 3 senior workers (HR, engineers), and 5 junior workers (mine workers, kitchen, laboratory, etc.) |

| Trade unions (national and local level) | 2 | Both men, 1 at the national level and 1 at the local |

| Local authorities | 3 | 2 men, 1 woman, from two subdistricts where the two mines are located |

| Lawyers | 1 | Male, district-level lawyer, who was involved in the mass firing of employees at Ishtamberdy |

3 The Case

3.1 Background

Kyrgyzstan’s economy is dependent on the gold sector, which accounts for 10% of GDP and 39% of exports. In 2021, Kyrgyzstan exported US$908 million in gold, and although this meant that Kyrgyzstan was only the 52nd largest exporter of gold in the world, gold was the primary export from the country.Footnote 12 Against this backdrop, foreign investment in gold mining areas has become a battleground for foreign investors, Kyrgyz authorities, the opposition, and local communities. Yet, because of its importance, the mining sector is identified as one of the priority sectors for the economy in strategic government papers concerning national development programs. These include the “National Development Program of the Kyrgyz Republic,”Footnote 13 which is in effect until 2026, and the “Concept of Green Economy in the Kyrgyz Republic.”Footnote 14

The employment structure in Kyrgyzstan mainly relies on agriculture and farming (18.3%), wholesale and retail trade (15.3%), construction (12.4%), and public services (health, education, etc.). Mining and quarrying employ only 0.7% of the workforce, with 17,900 people working in the industry. Yet this number has doubled since 2016. This increase can be explained by the Kyrgyz president Almazbek Atambaev’s active cooperation with China and the issuing of mining licenses to smaller deposits since the start of his term in 2011.

A number of gold deposits have been discovered in the Middle Tian Shan mountains in Jalal-Abad. This region is southwest of the capital, Bishkek, and is a rural, mountainous area that has been traditionally used as summer pastures for local livestock keepers.Footnote 15 Jalal-Abad incorporates both the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat mines, which are described in turn and in fuller detail below.

First, the Ishtamberdy mine was opened in 2011 as Kyrgyzstan’s second foreign-owned mine. However, its operations since then have been intermittent due to license suspensions imposed by the Kyrgyz government in 2013,Footnote 16 2016,Footnote 17 2018,Footnote 18 and 2023.Footnote 19 Such setbacks have nevertheless not yet resulted in the abandonment of the project, primarily because of the commercial opportunities it presents: Exploration studies indicate that the site contains 140 metric tons of gold.Footnote 20 This assessment places the Ishtamberdy mine among the larger of Jalal-Abad mines, whose gold deposits range from 34 tons (in Bozymchak) to 170 tons (in Chaarat). However, when compared to the Kumtor mine in the east, Ishtamberdy’s deposit is considered relatively small,Footnote 21 containing approximately a quarter of Kumtor’s 538-ton deposit.

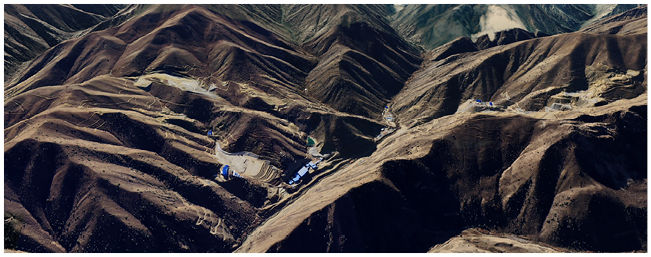

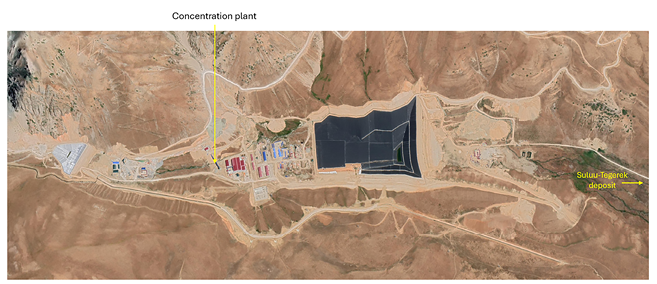

In terms of its operating capability, as Figures 4.2.1 and 4.2.2 show, the Ishtamberdy mine comprises surface mining works and includes a processing facility;Footnote 22 and the stated aim was to mine 300,000 tons of ore per annum and, from that ore, to produce 2 tons of powdered gold concentrate per annum.Footnote 23 However, it is unclear whether this aim has ever been realized because in 2016, when the mine was expected to start operating in full capacity, Ishtamberdy’s chief engineer announced that only 780 kg of gold concentrate would be produced.Footnote 24

Figure 4.2.1 Tilted view of Ishtamberdy mine

Figure 4.2.2 Aerial view of Ishtamberdy mine

In terms of the corporate structure of the Ishtamberdy mine project, the mine asset is owned and operated by Full Gold Mining Limited Liability Company (“Full Gold Mining”). It is a gold mining company and, according to Sayari, has one director and three shareholders. One shareholder is Lingbao Gold Company Limited (靈寶黃金股份有限公司),Footnote 25 a Chinese state-owned and Hong Kong-listed corporation that specializes in “mining, processing, smelting and sales of gold and other metallic products.”Footnote 26 A second shareholder is China Road and Bridge Corporation (中国路桥工程有限责任公司).Footnote 27 This may explain why, despite a primary focus on mining, Full Gold Mining appears to have diverse business interests that also include, for example, road building, which have been used to secure the rights to the Ishtamberdy project.

Although detailed corporate information relating to Full Gold Mining and the Ishtamberdy mine is generally inaccessible, online sources indicate that the Chinese company came into control of and assumed the authority to develop the mine in three complementary ways. First, on 16 January 2008, Full Gold Mining secured a twenty-year license from the Kyrgyz government, a necessary prerequisite for any mine development.Footnote 28 Second, Full Gold Mining’s acquisition was carried out through a multiparty Cooperation Agreement signed by Chinese and Kyrgyz parties from both the government and the private sector. On the Chinese side, signatories included China Development Bank, China Road and Bridge Corporation, and Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Lin Xi Investment Company, who all appear to have either financed the Ishtamberdy mine or supplied it with goods and services necessary for the mine’s operation.

On the Kyrgyz side, signatories included the Kyrgyz Ministry of Transport and Communications and the Kyrgyz State Agency for Geology and Mineral Resources, who played a role in regulating, licensing, and approving the Ishtamberdy project. Third, Full Gold Mining and the Kyrgyz government reached an agreement on “Resources in Exchange for Investment.”Footnote 29 Under its terms, Full Gold Mining would secure the rights to develop Ishtamberdy on the condition that it improved the local road infrastructure. Consequently, prior to securing Kyrgyz licenses, Full Gold Mining served as the “entity responsible for project implementation” in a project to restore 50 km of the Osh-Sarytash-Irkeshtam Road that was financed by the China Development Bank via a US$38.57 million loan.Footnote 30 A peculiar feature of this transaction is that, although the road project was not connected geographically to the Ishtamberdy mine, the China Development Bank loan was to be repaid out of revenues generated by the mine and not the road project.Footnote 31 Separately, and following an outcry from villagers, Full Gold Mining also paved the road linking local settlements surrounding the Ishtamberdy mine.Footnote 32 These developments suggest a high degree of willingness among prospective Chinese investors (as well as third parties who play a secondary and supportive role, such as banks) to do whatever is necessary to secure the required licenses and agreements with the host country irrespective of the Chinese investor’s core business operation.

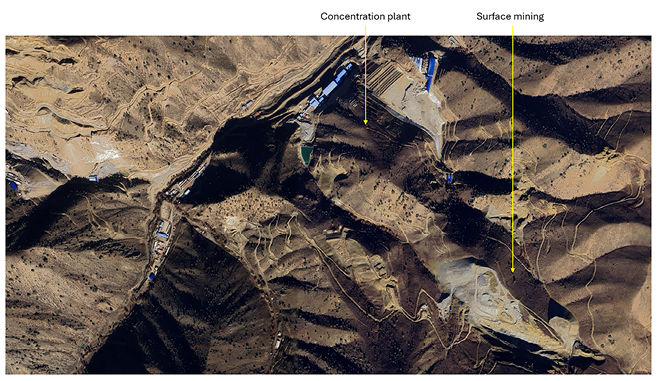

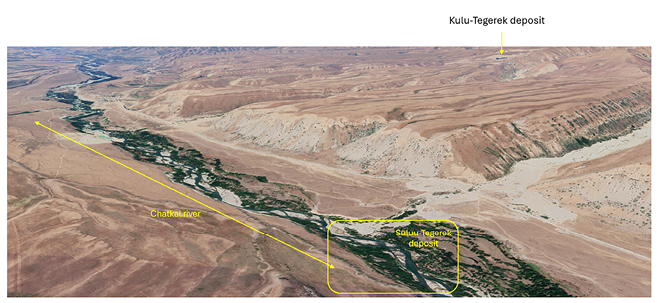

The second gold mine that this case study explores is the Kichi-Chaarat mine, which lies approximately 70 km to the northeast of the Ishtamberdy mine, separated by the Pikgora mountain. The Kichi-Chaarat mine opened in 2019;Footnote 33 and, like Ishtamberdy, operations at the Kichi-Chaarat mine have periodically stalled due to license suspensions. One such suspension occurred in 2022 and applied to Kichi-Chaarat’s Suluu-Tegerek deposit.Footnote 34 However, unlike Ishtamberdy, the Kichi-Chaarat mine falls into two parts (as it has two deposits) and operates different excavation methods.Footnote 35 The mine’s Kulu-Tegerek deposit is located up on a mountainside and incorporates a US$220 million underground mine and concentration plant for converting gold, silver, and copper ore into powdered concentrates (Figures 4.2.3 and 4.2.4).Footnote 36 According to AidData, “Upon completion, the mine was expected to have an annual processing capacity of about 1.8 million tons, including an annual output of 11,000 tons of copper, 600 kg of gold and 4.6 tons of silver. The annual sales from the mine were expected to be $100 million.”Footnote 37 Meanwhile, down the mountainside in the Chatkal valley’s riverbed lies the Suluu-Tegerek deposit, which incorporates a placer mine.Footnote 38 Such mines remove gold deposits from sediment in water, but information on its productive capacity (either projected or actual) is unavailable.

Figure 4.2.3 Aerial view of Kulu-Tegerek deposit at Kichi-Chaarat mine

Figure 4.2.4 Tilted view of Suluu-Tegerek deposit at the Kichi-Chaarat mine

The Kichi-Chaarat mine is owned and operated by Kichi-Chaarat Closed Joint Stock Company (“Kichi-Chaarat”), which is a special purpose organization established by Chinese equity investors to oversee the project. As with Full Gold Mining, little corporate information relating to Kichi-Chaarat is available. However, the available information indicates that it was owned by a succession of Canadian and Chinese companies. Specifically, a press release in 2004 indicates that Kichi-Chaarat was acquired by Eurasian Minerals, Inc., a Canadian firm, through a subsidiary called Altyn Minerals LLC.Footnote 39 Four years later, a United States Securities and Exchange Commission filing suggests that ownership had changed hands and that, in 2008, Kichi-Chaarat was owned by China Shen Zhou Mining & Resources, Inc. (a publicly listed firm whose shares were traded on what was then known as the American Stock Exchange) through a subsidiary called American Federal Mining Group.Footnote 40 Following this, online searches indicate that Kichi-Chaarat in 2013 was 84% owned by the China National Gold Group Corporation and 16% owned by China CAMC Engineering Hong Kong Company Limited. Furthermore, similarly to Full Gold Mining, Kichi-Chaarat also received support from other Chinese economic actors – in this case, loan financing from both the China Export-Import Bank in 2017 and Skyland (a subsidiary of China Gold International Resources Group Corporation Limited) in 2016.Footnote 41 A more recent example of this is illustrated by a company press release by the Shanghai subsidiary of China National Gold, which celebrated its work to quickly provide supplies to Kuru-Tegerek by utilizing a streamlined customs declaration procedure and a combination of trucks and trains:

On March 3, ten 40-foot containers loaded with RMB 4 million worth of mining machinery and equipment as well as production materials were released at Kashgar and Irkeshtam customs upon sealing inspection and transported to Kuru-Tegerek copper and gold mine in Kyrgyzstan through the Irkeshtam port. This indicated that the speed of the “China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan” highway and railway intermodal international freight train has been fully accelerated, in which China Gold Trading (Shanghai) was a major participator.Footnote 42

Overall, when considering the role of Chinese investment in the Kyrgyz gold mining sector, it is worth noting that, first, Chinese investors will seek to work in concert with Kyrgyz and Chinese stakeholders from both the private and public sectors not only to agree to the terms of their investments but also to procure the necessary financing and project supplies. Second, Chinese investors will exercise flexibility to fulfill the needs of Kyrgyz stakeholders, even if doing so requires providing business solutions or negotiation concessions that may be novel or unfamiliar. Third, ownership of Kyrgyz mines seems to be particularly dynamic with owners and investors from various nationalities involved at different stages.

3.2 Causes of Tension

Gold mines have occupied a prominent position in Kyrgyzstan’s national debates and political life. Over the last twenty years, local protests against foreign-owned mines have become more frequent in line with reducing employment opportunities, rising resource nationalism, and dissatisfaction among the local population who feel deprived from the income generated by the mines.Footnote 43 Political unrest has provided an opportunity for local community members to voice their demands to both the companies operating gold mines and state authorities. One example is the unrest that erupted in October 2020 led by local community members against gold mining companies, including those at the Chinese-operated mines at Kichi-Chaarat and Ishtamberdy. The protests caused production to halt for several days as the mines were seized by the local population. The local population’s grievances against the Chinese-operated mines were fueled by “perceived corruption, the lack of transparency, and discrimination against hiring local residents as well as environmental degradation.”Footnote 44

3.3 Opaque Hiring Practices

In late 2022, the Ishtamberdy mine had 585 employees and Kichi-Chaarat employed 129. Typically, Kyrgyz workers occupy various positions, from engineers, geologists and professional positions to regular miners, drivers, repair men, and so on. Women mainly work in the laboratories, kitchens, cleaning departments, and accounting and finance departments. Although our interviews have been unable to ascertain whether these staff numbers comply with Kyrgyz laws decreeing that the foreign labor force in a gold mine may not exceed 10%, recent news reports indicate that Ishtamberdy is compliant: Full Gold Mining, speaking about the Ishtamberdy mine, reported that 91% of workers were local Kyrgyz.Footnote 45

However, in general, Kyrgyz job applicants find it difficult to receive an employment offer from a mining company in Kyrgyzstan. Mining is a well-paid industry so finding positions is intensely competitive. Applicants seeking an edge have paid significant bribes, others have chased job opportunities for years. Seeking employment at Chinese-owned mines is particularly difficult; other foreign companies (i.e., Canadian, British, Turkish, and Kazakh) tend to have a greater degree of accessibility and transparency. They have official websites or social media pages where they announce vacancies. Although the likelihood of Kyrgyz applicants satisfying all the job requirements and being accepted is very low, potential employees at least are informed as to the eligibility criteria and requirements for the position.

3.4 The Human Resources Department as Gatekeeper

Now and then, the Kyrgyz employment websites announce vacancies at the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat mines, but most are for positions such as senior specialists or within the mine company’s Human Resources department. These departments consist of Kyrgyz employees and play a major role in shaping the employment policy of the Chinese companies. For example, they can shape Chinese companies’ current practice to allocate a quota for its local hires to local authorities, who then try to send their own associates, including relatives or family members (Chinese companies are not alone in adopting this practice). In some cases, positions are given to vulnerable families who have a low income or more children to co-opt those families who might otherwise have a grievance.

As characterized by a number of interview respondents, the Human Resources departments have over time built up power akin to the “mafia” (мафиянын уюгу) by hiring the “convenient” (кытайдын сөзүн сүйлөгөн) workers and firing the “inconvenient,” ones, that is, “the ones who speak justice, demand better meals, compensation for night shifts and raise other problems” (акыйкатты сүйлөгөн, тамак-ашты жакшыртуу, түнкү сменага төлөш боюнча жана башка көйгөйдү айткан). As a result, the “convenient” laborers have formed an alliance of like minds and fully obey the instructions of Chinese managers.

The Chinese managers themselves don’t participate in the hiring process as this is delegated to local subcontracting companies or locally hired human resources professionals. Due to these informal hiring practices, the process is seen as nontransparent by the local communities. For example, if an agitator is known for initiating demonstrations concerning environmental or other social issues in the villages near the mine, they have a better chance of being accepted for a job as a “silence reward,” meaning that they are hired in exchange for their acquiescence. One interviewee recalled: “[Full Gold Mining Company] told me clearly that in exchange for not being an activist and for not mobilizing people to participate in demonstrations against the mine, I would be offered a job (ачык эле айткан, сиз закондошпойсуз, элди үгүттөбөйсүз, ошондо алабыз деген).” Not only does this practice raise ethical questions; it also may risk alienating applicants who have not caused conflict, which, in turn, may precipitate further grievances later on.

3.5 The Utility of Personal Relationships

The easiest and most effective way of being hired in the mining industry is through Kyrgyz acquaintances who already hold senior positions particularly in the Human Resources departments. Alternately, would-be employees need to have influential contacts with Kyrgyz authorities (e.g., such as law enforcement agencies). Of the twenty-two people interviewed, thirteen were hired because they knew someone influential.

Utilizing ties based on a combination of acquaintances, relatives, village neighbors, patrilineal ties, and clan members (тааныш-билиш) is a similar route to employment. For instance, if the senior HR person (Kyrgyz) is from one clan or certain village, most of the employees will be from the same clan or village. Because of the strong affiliation to clans, it is not uncommon for employees from different clans to develop confrontational relationships, which affects operations.

In general, people living close to the mines have a better chance of being accepted, as they are most likely to be affected by the environmental impact of mining activities – such as shoddy maintenance at the Ishtamberdy mine causing the effluent to enter the river, which serves as a water source for nearby villages.Footnote 46 People from the affected village would be prioritized for employment. Although regulations on the procedure for licensing subsoil use do not mandate hiring employees from the nearby villages,Footnote 47 it is the company’s policy to prioritize hiring local people as “compensation.”

3.6 Difficulties with Employment Contracts

Mining is one of the sectors that has a low percentage of informal employment in Kyrgyzstan, meaning that almost all workers have a contract. However, at the beginning of the projects, while the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat mines were being established, there was a window of time during which many workers may not have had formal written contracts. The main issue with labor contracts is their term and how they are used to remove agitators. According to the Labor Code of Kyrgyzstan, contracts are concluded for a specified period not exceeding five years or for an indefinite term if the position is permanent. If the job is temporary in nature, contracts can run for a fixed term.Footnote 48 This mismatch (permanent or temporary) is used by many employers, not only by mining companies, across the sectors. Mining companies tend to offer fixed-term contracts for six months or one year, based on their view that the job is temporary. Interviews revealed that these fixed-term contracts have caused labor violations.

For instance, in Ishtamberdy mine, a one-year contract can be used to remove “inconvenient” workers who openly criticized labor conditions and demand more decent working conditions. Hence, workers could be fired without notice, including without sick leave and mandated holiday pay. Employment contracts have also been terminated for other reasons: After the protests in October 2020, nearly forty people (all men aged fifty-five and higher) were fired in a clear example of age discrimination. Kyrgyz law states that the retirement age for men is sixty-three,Footnote 49 but it includes a caveat stating that men working in mining can retire early if they have twenty-five years’ work experience.Footnote 50 Most of the men fired did not have twenty-five years’ experience and on this basis the mass termination of their contracts did not fulfill the caveat.

3.7 Insufficient Equipment and Unsafe Conditions

The interviews indicated that safety measures adopted by Chinese companies are relatively poor compared to other mines operated by other nationalities. The main reasons are the lack of financing for security measures (e.g., no first aid systems in place) and the incompetence of the responsible employees. The issue of health and safety in the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat mines has been further compounded by a lack of cooperation with the Ministry of Emergency Situations in cases of emergencies and accidents. Previously, the companies paid a salary to the officers of the Ministry and, in case of accidents, an official rescue team would help, but this cooperation has stopped.

These issues mean that workers take responsibility for their own safety, for example, by buying special uniforms and equipment themselves when the company’s equipment was broken or worn (e.g., including small items such as flashlights). Doing so, however, has unfortunately failed to avert mine accidents. According to interviewees, five persons died in the Ishtamberdy mine in 2022. This included two employees who died of carbon monoxide gas poisoning (and another ten were injured) as the mine did not provide gas masks and mine tunnels were not sealed properly.Footnote 51

Another problem is that all instructions for the machinery is in Chinese. Most local workers cannot read Chinese and this problem is heightened during times of emergency, which are often time critical. The language gap is particularly pronounced by the fact that the Chinese companies do not provide training in the local language.

3.8 Complying with Salary Laws

The latest information on the average salary by sector shows that the mining sector has among the highest-paying jobs, together with manufacturing, information and communication, and the finance and insurance sectors. On average, employees receive about US$400 per month, whereas the average salary, across the largest sectors (agriculture, construction, trade, and public sector), is about US$150–200 per month.Footnote 52 However, in Ishtamberdy, the salary of workers is around US$230–250, which is significantly lower than the sector norm. In addition, in violation of local law, night shifts and extra hours are not paid.

According to the Labor Code of Kyrgyzstan, the mine workers’ salary should have the following bonuses: high-altitude coefficient (30%), level of danger (30%), and night shifts (50%). Most mines are located above 3,000 m; therefore, mine workers should get at least the high-altitude coefficient. However, such bonuses are rarely granted. The representative of Kyrgyz Geology Trade Union stated:

When we negotiate with Chinese companies, they say that they do not have the concept of high-altitude coefficient for the salary. They have a fixed salary of 30,000 som.Footnote 53 It includes night shift, high-altitude coefficient, and harmfulness. They say they don’t have this in China.

We explain to them that all employers working in Kyrgyzstan, regardless of their form of [company] ownership, are subject to the Labor Code of the Kyrgyz Republic. That is, they comply with labor laws.

We have these problems, at the initial stage of interaction, when preparation work is already being carried out. Chinese investors involve lawyers and the lawyers also explain [the requirements] to them. This stage lasts six months or a year; almost all companies have this tendency. Chinese companies are not immediately ready to comply with local labor laws; they need to be explained, convinced, and proven that this must be done. […]

At the beginning, an employment contract is not concluded, only a salary is paid. When the process begins, trade unions are created and people begin to contact the labor inspectorate, [only then] problems are exposed.

And accordingly, [when] a dispute begins, we have several legal companies, Chinese consulting companies, and they explain their rights. The Chinese company leaders contact them, and it becomes clear that our demands are correct.

In summary, although mining salaries are among Kyrgyzstan’s highest, there is a sense of injustice among workers in Chinese-owned mines who argue they are not receiving their full entitlement. There is also a view that the process of educating and persuading Chinese investors to pay the full entitlement is long and painstaking.

3.9 Working Conditions

According to the workday calendar approved by the Kyrgyz government,Footnote 54 mine workers should work a maximum of thirty-six hours per week. In reality, however, they often work up to fifteen additional hours, which goes unpaid. Sick leave is paid in Kichi-Chaarat, but in Ishtamberdy it depends on the negotiating and persuasive skills of the applicant. If successful, they can receive compensation.

Accommodation and food also need improvement. Accommodation in Ishtamberdy mainly consists of shipping containers, six to eight people in one room, and accommodation conditions for Kyrgyz workers are definitely poorer than those provided for Chinese workers.

3.10 Grievances

Since 2010, when Chinese mining companies first began active mineral exploration in Kyrgyzstan, there have been numerous social and environmental conflicts due to mining operations. Participants from the surrounding villages have blocked roads, attacked mine sites, and engaged in other forms of protest. Because of corruption and instability within the political system in Kyrgyzstan, citizens often cannot resort to official channels for redress. Rather, historically, grassroots movements, including demonstrations, have been a more effective means of expressing civil disobedience and protecting social and economic rights. This is particularly so in the context of the mining sector.Footnote 55

Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat have both seen a number of conflicts related to environmental problems, as expressions of disagreement by the local people to the mining process. This kind of demonstration serves also as a platform where local communities not only expressed grievances but also, and perhaps demonstrating a peculiarity of the Kyrgyz mining industry, expressed their willingness and ability to resume work in the hope that their protests would result in obtaining employment.

3.11 Mine Protests

Since the opening of the Ishtamberdy mine in 2011, at least three instances of service disruption have been documented. First, in 2012, workers called a strike. This led to a 30% pay rise (but less than the 50% being sought).Footnote 56 Later, in 2018, nearly 400 workers were dismissed for refusing to accept contracts with lower pay (which was driven by Ishtamberdy mine’s poor financial performance). The vice president of Full Gold Mining elaborated:

Our company has been suffering losses since it began to work. We invested US$200 million in the deposit. At least 958 million som have been spent on the payment of wages. Workers are very expensive, so we decided to change the terms of the contract. We ask for help to survive a difficult period together. The funds invested have not yet paid off. In order not to become bankrupt, we are forced to take such steps.Footnote 57

The mass dismissal of workers led to villagers from Kizil-Tokoi and Terek-Sair forming a protest and, in turn, a suspension of operations at Ishtamberdy.Footnote 58

In 2020, protestors alleging electoral fraud in the 4 October presidential elections also stormed the premises of Full Gold Mining.Footnote 59 This occurred during a period of civil unrest across Kyrgyzstan in which the Kyrgyz White House and Supreme Court were also occupied. The precise motivations for storming the premises are unclear and may have been driven by frustrations beyond the mine itself: government corruption, socioeconomic inequalities, and the presence of foreign-controlled companies in Kyrgyzstan.Footnote 60

Although there are fewer documented instances of unrest at the Kichi-Chaarat mine, the mine has not been insulated against similar incidents and in 2020 “tightened security at its mine, anticipating riots by the locals.”Footnote 61

3.12 Inaccessible Justice

Resolving large-scale labor disputes has typically been achieved through negotiations between companies, employees, local and national authorities, and labor unions. Both the government and the companies are interested in not publicizing the disputes and try to resolve conflicts internally.

As for labor disputes initiated by individual workers, litigants officially have recourse to the courts and there are regular court cases. However, most of the local employees have little legal knowledge and thus do not seek recourse in courts. If they are fired or face any labor rights violation, they usually address the local municipality or district level authorities, or simply keep believing the promises of Chinese company representatives.

These issues are further compounded by a number of factors, one of which is that information on court cases is hard to find in the state register,Footnote 62 unless you know the full information on the case. This difficulty renders jurisprudence inaccessible and imposes a constraint on litigants and their legal advisors, thereby placing them on the back foot vis-à-vis businesses such as the Ishtamberdy and Kichi-Chaarat mine owners who have their own in-house counsels.

In the meantime, according to Kyrgyz law, a person should address the court with a complaint regarding unfair termination within two months of being fired. The procedure for addressing the complaint is also quite complicated as employees need to have a conclusion from labor inspection. This requirement creates a significant time delay for filing that in the past has impeded a number of suits. For example, interviewees reported losing their age discrimination case(s) because the case(s) expired due to such time delays.

3.13 The Role of Government Agencies

Government agencies and local authorities tend to have insufficient experience and capacity to deal with enforcement issues. For example, corruption is a deep-seated problem, and while some argue that corrupt practices can actually help address certain issues, in general, corruption exacerbates systemic problems. Specific to Chinese investors, local authorities and high-level authorities (e.g., deputies of the Kyrgyz Parliament) have been known to form affiliated companies that win subcontract tenders from the Chinese. Consequently, they may exhibit a protectionist attitude toward Chinese investors even if those investors are violating local environmental and labor rules. This problem creates resentment among local residents who have groups, including on social media, where they share information on, for example, corrupt actions by local government and the nontransparent practices of Chinese investors. These resentments likely resulted in the 2020 election protests.

Local authorities often do not have sufficient human resources to work effectively with Chinese and other foreign investors. In the Chatkal district where several mines, including the Kichi-Chaarat mine, are located, there is only one official responsible for communicating with all mining companies and who seems not to have any background in mining.

In cases of conflict, local employees and communities are known for mobilizing online social media platforms, as well as using demonstrations, to put pressure on national decision makers. The authorities then form national commissions to address the issues, but little seems to be achieved. The president may also be called upon to intervene directly in the matter – even when it may not be entirely appropriate to do so. The effectiveness of such commissions and presidential interventions is therefore questionable.