Book contents

- Chinese Politeness

- Chinese Politeness

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Prologue

- 1 Pragmatics, Politeness, and Chinese Politeness

- 2 Hierarchy and Harmony: Roots of Chinese Face and Politeness

- 3 Chinese Face

- 4 Chinese Politeness and Theories of Politeness

- 5 Synchronic Consistency and Variation

- 6 Diachronic Stability and Change

- 7 In Comparison with East Asian Languages

- 8 In Comparison with English: An East-West Divide?

- 9 Politeness Theories

- Epilogue

- References

- Index

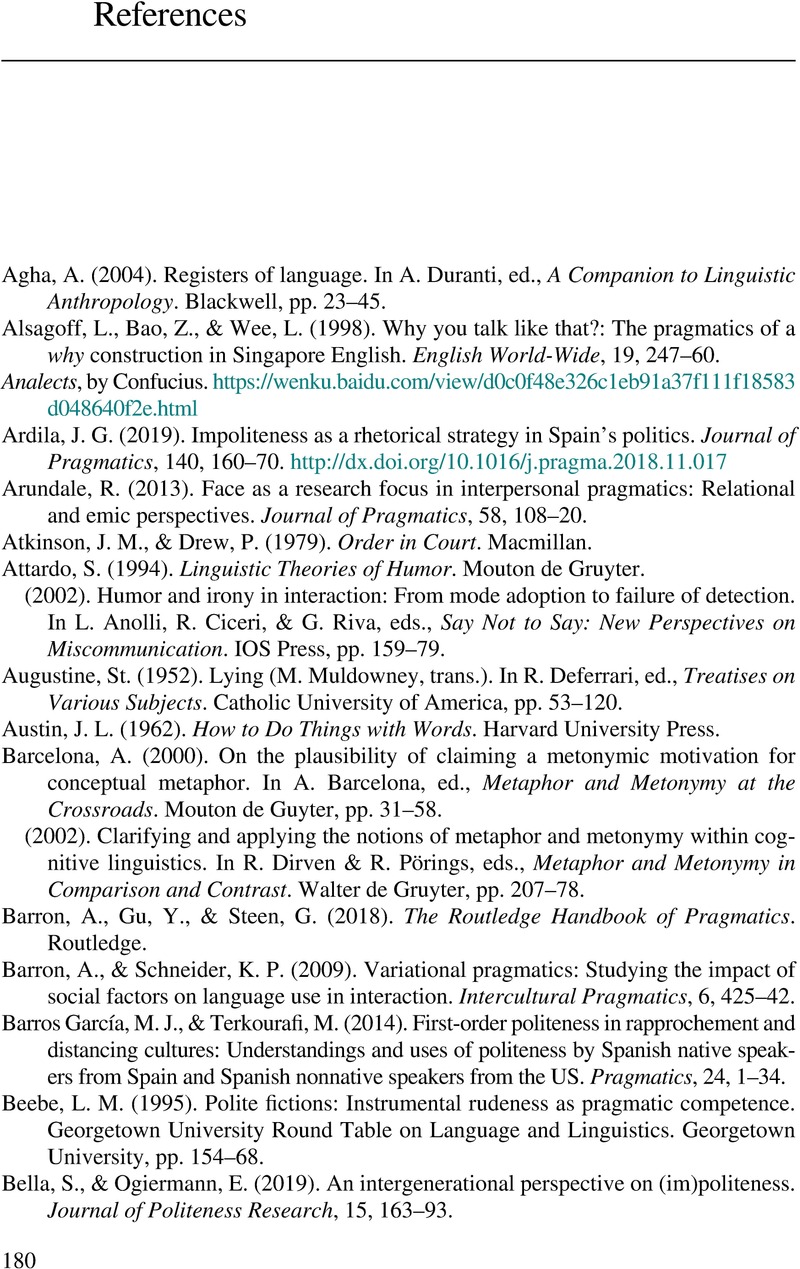

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 November 2023

- Chinese Politeness

- Chinese Politeness

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Prologue

- 1 Pragmatics, Politeness, and Chinese Politeness

- 2 Hierarchy and Harmony: Roots of Chinese Face and Politeness

- 3 Chinese Face

- 4 Chinese Politeness and Theories of Politeness

- 5 Synchronic Consistency and Variation

- 6 Diachronic Stability and Change

- 7 In Comparison with East Asian Languages

- 8 In Comparison with English: An East-West Divide?

- 9 Politeness Theories

- Epilogue

- References

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Chinese PolitenessDiachrony, Variation, and Universals in Politeness Theory, pp. 180 - 199Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023