The revolutions of 1848 set Europe ablaze. The flames erupted in Paris on February 22 and soon spread north, south, east, and west. In short order, the fiery revolutions leapt from France into the Caribbean Sea and onto the American mainland.Footnote 1

The 1848 revolutions impacted American domestic and foreign policy as they increased the need for agricultural labor in the West Indies, elevated fear of abolition among southern slaveholders, and brought disappointed European revolutionaries to seek new opportunities across the Atlantic.Footnote 2 Importantly, the European revolutions of 1848 resulted in slavery’s abolition in both the French and Danish West Indies and served as a striking example of the transnational ties between Europe and the New World.

On February 25, 1848, the French provisional government “declared a republic and also emancipation with indemnity” on the slaveholding islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique, in part due to fears of slave revolts such as the one that led to Haitian independence in 1804.Footnote 3 As Rebecca Schloss has shown, events in the West Indies soon overtook political decisions on the mainland about the practical transition to free labor.

[O]n May 22 more than twenty thousand enslaved workers crowded the streets of Saint Pierre, Martinique demanding their freedom. Shortly afterward, the island’s governor proclaimed emancipation and initiated a new chapter in the complex interplay of race, class, and gender in the French Atlantic.Footnote 4

By July 1848 the French West Indian unrest, and ensuing emancipation, served as partial inspiration for an uprising on the neighboring island of St. Croix in the Danish West Indies (see Figure 1.1).Footnote 5 Thus, Governor Peter von Scholten concluded that the islands’ enslaved population would wait no longer for freedom. A widespread but generally peaceful uprising on St. Croix in July settled the matter.Footnote 6

Figure 1.1 French depictions of abolition in the West Indies, such as this one by artist François-Auguste Biard, mirrored those in Denmark and underscored the pervasive Old World colonial mindset.

Von Scholten’s emancipation had not been authorized by King Frederik VII, however, and the governor was promptly replaced by councillor of state Peter Hansen, who was tasked with reorganizing labor relations between a planter class who felt betrayed by the Danish government’s failure to ensure the twelve-year transition period promised them in 1847 and the newly freed laborers who demanded better work conditions.Footnote 7 From Governor Hansen’s perspective, retaining control of the labor force was the main objective, and, following the lead of larger European powers, not least Great Britain and France, Danish officials by the late 1850s looked to amend American colonization policy to augment the islands’ labor force.Footnote 8

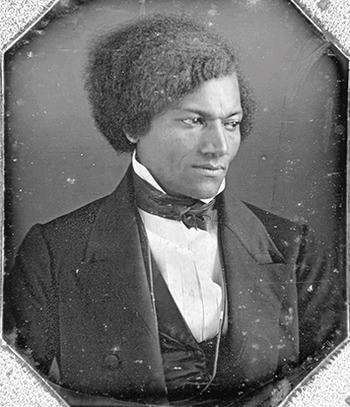

During the early 1860s, colonization in the United States was legally directed toward Liberia, but – in no small part due to Danish diplomats – the policy was reoriented to also include the Caribbean.Footnote 9 Moreover, slavery’s abolition in the Danish and French West Indies sparked fear, as well as jubilation, in the United States.Footnote 10 In the immediate aftermath of emancipation in the West Indies, southern slaveholders peered somewhat fearfully toward the Caribbean emancipation initiatives.Footnote 11 In New York, Frederick Douglass, abolitionist and editor of the North Star after his escape from slavery, remarked optimistically in 1848 that the revolution initiated in Europe flashed “with lightning speed from heart to heart, from land to land,” until it would eventually traverse the entire globe (see Figure 1.2).Footnote 12

Yet by 1851 it was clear that American abolitionists would have to bide their time, as most nations on the European mainland had reverted back to their prerevolution roles in an uneasy equilibrium of monarchical and imperial power balanced mainly between Russia, France, Great Britain, Austria, and the German states.Footnote 13

On the European mainland, underlying social issues and overarching political structures tied population groups together across borders. Uprisings in Frankfurt in 1833, Paris in 1839, and Kraków in 1846 attested to the widespread political, social, and economic discontent across Europe.Footnote 14 In Wolfram Siemann’s words, lack of political participation, the urge for national self-determination, a crisis of “pre-industrial craft trades,” and failed harvests resulting in famine were key driving forces behind uprisings in the spring of 1848.Footnote 15 As a result, revolutionary sentiment among nationalist and politically marginalized groups within Scandinavia, France, Italy, Poland, and Germany sparked uprisings across the continent that simultaneously strengthened and challenged nationalistic ideas within existing borders. In Northern Europe, along Denmark’s southern regions, embers that had smoldered for years suddenly burst into flames and led to a civil war within the kingdom that revealed tangible divisions along political, ideological, social, ethnic, national, separatist, and dynastic lines.Footnote 16

Despite his personal resistance to democratic reform, King Christian VIII had prepared an eventual transition from absolutism to constitutional monarchy before his death on January 20, 1848. This political move toward at least nominal democracy based on a moderately liberal constitution was accepted by the new king, Frederik VII, in the so-called January rescript of January 28, 1848, the commitment to which was strengthened and reiterated after a sizable but peaceful demonstration by an estimated 20,000 people in Copenhagen on March 21, 1848.Footnote 17

In Sweden and Norway, the European revolutions fueled protests in Stockholm and a popular Norwegian movement led by revolutionary Marcus Thrane, but the relatively well-functioning political system in Norway (based on the Eidsvoll Constitution of 1814), coupled with an eventual crackdown by the authorities on Thrane “for conspiracy against the state” in July 1851, prevented the movement, which at its height attracted close to 30,000 followers, from gaining even wider traction during these years.Footnote 18

Despite the largely peaceful political responses to grassroots dissent, King Frederik VII’s decision to move toward constitutional monarchy left a power vacuum within the Danish kingdom. Danish- and German-speaking nationalists both seized this European revolutionary moment, hoping to shape the Danish kingdom’s future according to their own interests.Footnote 19

On Denmark’s southern border, the key point of contention was the status of Schleswig and Holstein.Footnote 20 Since the so-called Ribe Treaty of 1460, the duchies Schleswig and Holstein had been united, based on an understanding that they would remain forever undivided (“up ewig Ungedeelt”).Footnote 21 Hereafter, the Danish monarch became the Count of Holstein and also incorporated the duchy of Schleswig under Danish rule.

The rise of nationalist sentiment among Danish speakers throughout the 1840s, concretized in a political faction called “nationalliberale” (national liberals), led to calls for the consolidation of the Danish kingdom more clearly along cultural and linguistic lines, by dividing Schleswig from German-speaking Holstein along Ejderen, a river running east–west toward the important seaport of Kiel.Footnote 22 Conversely, the population within the Danish kingdom’s borders who identified as German took the revolution in France as a touchstone for their own nationalist claims. On March 18, 1848, less than a month after the revolution’s outbreak in Paris, German-speaking residents of Schleswig-Holstein demanded that the duchies remain undivided with the aim to break away from Denmark. The Danish king dismissed the German-speaking Schleswig-Holsteiners’ petition and instead made statements about incorporating Schleswig without Holstein directly under Danish rule. The irreconcilable positions led to German separatists seizing a Danish fortress in Schleswig-Holstein on March 24, 1848, and forming a “provisional state government.”Footnote 23

This civil war, now known as the First Schleswig War, lasted from 1848 to 1850.Footnote 24 In accordance with the threshold principle, the national liberals feared that Denmark would become a mini-state, if it lost part of Schleswig and all of Holstein, and therefore started to explore Scandinavian alliances.Footnote 25 Pan-Scandinavian sentiment was especially strong among the younger Scandinavian intelligentsia, in spite of the relatively modest 387 Swedes and Norwegians (several of whom would eventually end up in the American Civil War) who volunteered to fight against German separatists.Footnote 26 The spirit of pan-Scandinavianism, however, was concretized at the political level when Sweden, prompted by King Oscar, sent 4,500 troops to defend Denmark’s monarchical rule against the German-speaking rebels, with the promise of up to 15,000 troops in all if the Danish mainland were to be invaded (safeguarded by the provision that Sweden would then have to be part of a broader international coalition led by Great Britain and Russia).Footnote 27

Yet the pan-Scandinavian enthusiasm proved to have notable diplomatic (and nationalist) limitations when confronted with the complexity of high-level European politics. In just one of numerous factors complicating the First Schleswig War, Denmark and Sweden had been on opposite sides for parts of the Napoleonic Wars, and the peace conference of 1814 in Kiel forced Denmark to cede Norway (which had been part of the Danish Kingdom since 1380) to Sweden.Footnote 28

Thus, despite several ambitious attempts, a pan-Scandinavian state incorporating northern Schleswig but excising the German-speaking regions found little concrete backing among more experienced Scandinavian power brokers, not least Danish conservative leaders who insisted on keeping the entire state together to maintain the territory and population already under Danish rule.Footnote 29

Additionally, there was a strong sense among Europe’s great powers, especially Great Britain and Russia, that German control of the important Schleswig harbor of Kiel was undesirable as it would help German Grossstaatenbildung.Footnote 30 Consequently, Russia and Great Britain worked actively to curtail the armed conflict and protect Danish territorial sovereignty in the name of stability (as opposed to revolution or disruption of the international trade). Thus, through the great powers’ intervention, the pre-1848 borders were eventually reestablished.Footnote 31

Across Europe, the lack of revolutionary result caused thousands of disappointed “Forty-Eighters” to seek freedom and liberty elsewhere – and many in the United States.Footnote 32 Even in Scandinavia, where the 1848 revolutions had prompted King Frederik VII to sign grundloven (the Constitution), the effect for people with little economic or political power was negligible. Consequently, a steady emigration from Scandinavia started picking up speed, especially from rural areas.

Additionally, decisions to emigrate were likely accelerated among the German-speaking population in Schleswig and Holstein by the Danish government’s determination to impose strict language requirements and banish revolutionary leaders such as Hans Reimer Claussen and Theodore Olshausen, both of whom eventually ended up in America.Footnote 33 When Claussen arrived in Davenport, Iowa, he apparently found a welcoming community of a “large number of his closest countrymen, the Schleswig-Holsteiners.”Footnote 34

Other German-speaking subjects living within Danish borders struck out for Wisconsin, as was the case for August Hauer, who arrived with his family in what became New Denmark (and who, according to one account, “was a mortal enemy” of everything associated with the Danish state for decades afterward).Footnote 35

The exact number of German-speaking Forty-Eighters who emigrated for political reasons after the First Schleswig War is difficult to ascertain, but the legacy of the 1848 revolutions in terms of political rights, economic opportunity, and abolition of slavery continued to impact American and Scandinavian society in the years afterward.Footnote 36

Whether settling in Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, or Minnesota – or, for a few, even Missouri, Louisiana, or Texas – the German, Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian Forty-Eighters who emigrated in the wake of the revolutions generally found some common ground in their interpretation of equality and liberty. Despite Old World divisions, these Northern European immigrants’ experience with class divisions would continue to shape their engagement with issues of social mobility and equality in America. At the very center of such discussions was the importance of owning land.Footnote 37