13 - GE-14 in Johor: Shock or Just Awe?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 April 2020

Summary

INTRODUCTION

Johor, Sabah and Sarawak were traditionally seen as Barisan Nasional's “safe deposits”, consistently delivering substantial numbers of parliamentarians and solid state-level majorities to the ruling coalition. Conventional wisdom held that should one or more of these fall, BN's hold on power would be seriously compromised. All three states were lost by BN in the aftermath of GE-14—albeit in different ways.

This chapter, for its part, will focus on Johor. With some 3.7 million citizens and residents, it is Malaysia's third largest state and has the second largest number of parliamentarians. Johor is ethnically mixed as—in addition to its bumiputra majority of 60 per cent—it has substantial numbers of Chinese and Indian voters, comprising 33 and 7 per cent of the state's citizens respectively (DOS 2017).

Johor's level of urbanization of 72 per cent closely mirrors the national average, meaning that many look to it as a bell-wether for national voting trends (DOS 2013). Of the state's twenty-six parliamentary constituencies, nine are urban or semi-urban and ethnically mixed. Many of these are in and around Johor Bahru and—due to long-established manufacturing operations as well as the more recent Iskandar Malaysia special economic zone—are relatively well-off. Conversely, the remaining seventeen constituencies are rural and mostly Malay-majority, grouped in the state's centre or on its coasts.

Johor's unique historical development, due to its lineage of dynamic traditional rulers, early exposure to commodity exports, and multiethnic character make the state important to Barisan Nasional (BN). The United Malays National Organization (UMNO) was founded in Johor in 1946, and the state produced a disproportionate number of the party's leaders and Cabinet members in the immediate postindependence period. For the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), the state's large Chinese population and economic importance have meant nearly all of the party's leaders have a connection with Johor, either living there or helming its state branch during their political careers.

Indeed, from the first elections in 1959 until 2013, BN never yielded more than one parliamentary seat or a handful of state seats to the opposition. And, relative to the national average, levels of support for BN in the state remained considerably higher. However, a rather less stellar performance in GE-13—along with unprecedented changes in the country's political context—heralded the beginning of a transformation.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

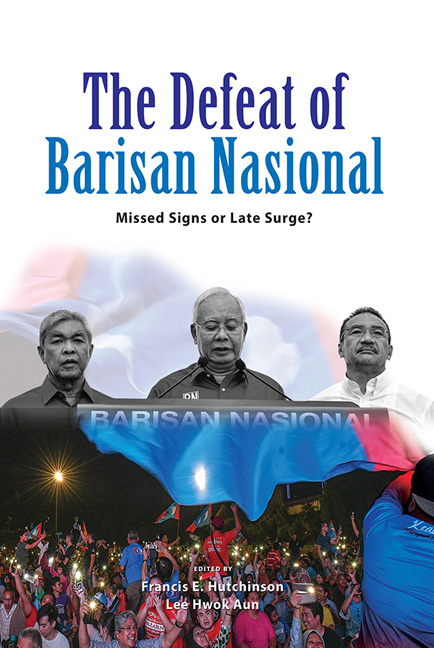

- The Defeat of Barisan NasionalMissed Signs or Late Surge?, pp. 310 - 341Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2019