The greater number of the cells are tenanted all day long, except for the little respite of chapel and exercise, and you may partly tell by the pallor of the tenant’s face how many days, weeks, or months of his sentence he has worked out in changeless solitude. If the doctor – whose duties, by the way, are infinitely the most responsible in the prison – has certified him fit for labour … he is put at once upon a purely penal task, which is generally as unprofitable as it is unpleasant.… They depress, irritate and degrade men of any feeling and intelligence.Footnote 1

Towards the close of the nineteenth century English and Irish prisons still contained and retained large numbers of mentally ill inmates, a situation acknowledged and deplored by the prison services in both countries. Prisons were declared inappropriate for the incarceration and treatment of mentally disordered prisoners as well as the increasing numbers of weak-minded inmates, who disrupted their management and were unable to bear or profit from the discipline. Prison officials and prison medical officers, however, were far less willing to attribute mental disorder to prison regimes and conditions, clinging to the mantra that most insane inmates were already suffering from mental illness when they entered prison. In contrast, critics of late nineteenth-century prisons, reform groups and former prisoners, drew attention to the apparent failure of prisons in terms of their cruel and ineffective discipline, the high rate of recommittals and their poor governance, with Edmund Du Cane, responsible for both local and convict prisons in England, the subject of particularly robust criticism.Footnote 2 They also highlighted the high incidence of mental breakdown in prisons, which they attributed directly to severe prison regimes. As shown in the quotation above, novelist and penal reformer Tighe Hopkins emphasised in 1895 how prison discipline degraded, irritated and depressed, adding his voice to those of many prison writers who described the eroding of mental energy, the bleakness and misery of prison systems designed to isolate and dehumanise their inmates. In particular, campaigners lobbied for the end of the separate cellular system that had dominated prison policies and practices since the 1840s.

Prison Psychiatry and Campaigns for Reform

By the 1890s this pressure, which via the press, novels and periodical articles increasingly built public support, prompted a reassessment of deterrent penal policies. The Howard Association, as seen in Chapter 4, intervened in cases highlighting poor treatment or brutality in prisons. The Association’s Secretary William Tallack had long been a critic of Du Cane, and had given evidence to the Kimberley Commission in 1878, pointing to the neglect of prisoners and instances of cruelty. The Humanitarian League, meanwhile, publicly stated that the prison system was ‘pitiless, indiscriminate and needlessly and culpably severe’.Footnote 3 In January 1894, the Daily Chronicle published a series of articles, ‘Our Dark Places’, presumed to have been written by Reverend W.D. Morrison who was associated with the Humanitarian League, but more likely authored by the newspaper’s assistant editor H.W. Massingham, who had toured a number of prisons shortly before the articles appeared.Footnote 4 The articles described prisons as gloomy, severe and obsolete, and referenced the ‘nervous strain of a prisoner’s life’, with prisoners subjected to silence and morbid introspective hopelessness.Footnote 5 Coinciding with a wider spiritual revival and growing concern about urban conditions in England, penal practices and conditions were also criticised by the Salvation Army. Many discharged convicts came under their care, ‘mentally weak and wasted’, suffering a loss of identity, and incapable of pursing ordinary occupations.Footnote 6

In Ireland it was the 1884 Royal Commission on Irish Prisons that highlighted the flaws in the treatment of prisoners, including the confinement of those suffering mental illness. In the 1880s, the imprisonment of leading nationalists, including Charles Stewart Parnell and John Dillon, had brought Irish prisons to the public’s attention, prompting the establishment of the Royal Commission. It was concerned with assessing whether the Irish prison system was administrated with ‘intentional or systematic harshness’.Footnote 7 Much of the Royal Commission’s criticism focused on unsanitary conditions in prisons, particularly at Omagh Prison, where the Governor had died of typhoid in 1882. The Report also highlighted the excessive punishment of refractory prisoners whose ‘mental condition may be described as the borderland between sanity and insanity’, and recommended the appointment, in a similar way to England, of a Medical Inspector or Superintending Medical Officer.Footnote 8 In general the Royal Commission was critical of local prisons in Ireland, and of the management of the prison estate, with allegations that Charles F. Bourke, Chairman of the General Prisons Board from November 1878 until 1895, was dictatorial in his style and his relationship with the prison inspectors was acrimonious.Footnote 9 While less critical of convict prisons, the Commission oversaw the closure of Spike Island in 1884, as recommended by the 1878 Kimberley Commission.Footnote 10

While Ireland did not hold an equivalent to the Gladstone inquiry, its Royal Commission aired similar concerns about the deleterious effects of punitive prison discipline. Meanwhile, Irish political prisoners added powerful voices to the mounting criticism of the English prison system where many had served time, giving evidence to both the Kimberley Commission and the Departmental Committee on Prisons (Gladstone Committee) in 1895. Chiefly focused on the situation in English prisons, Gladstone can be regarded as emblematic of the change in tone in both England and Ireland and growing public distaste for prison policies and practices. The 1895 inquiry, chaired by the Liberal Herbert Gladstone, Parliamentary Under Secretary at the Home Office between 1892 and 1894, included three other members of parliament – the Liberal and lawyer, Richard Haldane, Conservative Sir John Dorington, who had experience as a lunacy commissioner, and Irish nationalist member, Arthur O’Connor – along with the magistrate to the London police courts, Albert De Rutzen, Dr J.H. Bridges and an expert on women’s labour questions, Miss Eliza Orme. The Committee heard a wide range of evidence from witnesses based within and without the prison system, and visited six convict prisons and seventeen local prisons.Footnote 11 They also drew parallels with conditions in Irish prisons, referencing the findings of the influential 1884 Royal Commission.Footnote 12

One issue that emerged strongly in the evidence presented to the Gladstone Committee was the excessive rate of mental disorder among prisoners and the equally excessive demands this imposed on prison medical officers. While far from being a typical prison, the detailed inquiry into Holloway Prison, shone a light on the stresses in both prison systems. Magistrates in England and Ireland were still remanding in custody large numbers of prisoners whose mental state was suspect, and as Holloway replaced Clerkenwell as London’s chief remand prison in 1886 it bore the brunt of these admissions in England. As Medical Inspector Dr Robert Gover pointed out, ‘in London the sending of insane persons to prison under sentence is in great measure prevented by making use of Holloway Prison as a place in which accused persons can be observed and tested’.Footnote 13 In 1889, 401 prisoners of ‘doubtful insanity’ were remanded there for observation, and of these 215 were declared sane, 107 of weak or impaired intellect and 85 were reported to be insane.Footnote 14 The Gladstone inquiry also underlined Holloway’s huge turnover of prisoners, a situation mirrored only in one other English prison, Liverpool, which had around 18,000 admissions per annum by the mid-1890s.Footnote 15 In 1893–94, 12,467 males and 9,701 females passed through Holloway Prison, and its medical officer, Dr George Walker, had to examine between 20–30 and 80–90 prisoners each day.Footnote 16 Medical inspections were by necessity brisk, given Walker’s many other duties. However, reporting on the mental state of prisoners was highlighted by Walker as a task requiring ‘great care’ and the ‘most important duty’ of a prison medical officer, and he pointed out that making these assessments might require two to three examinations per prisoner.Footnote 17 In 1894 Walker claimed to have examined 1,056 such cases, some remanded by the magistrates for observation, while others had committed a serious crime or were suicidal and regarded by the medical staff as ‘special cases’.Footnote 18

As with the 1884 Royal Commission on Irish Prisons, the evidence presented to the Gladstone Committee revealed an ongoing reluctance to acknowledge the impact of prisons in producing mental disorder, which, as Chapter 2 has shown, was already very evident in the 1840s as the separate system was being established. In the year ending March 1893 some 88 cases of insanity were recorded in Holloway, 72 of whom were remand prisoners and ‘insane before they came in’. Their insanity, Walker declared, had nothing to do with their imprisonment in Holloway, and a great many had been in asylums before and some frequently in prison.Footnote 19 It was also claimed that of 354 cases of insanity in local prisons in England for the year ending March 1894, in only 60 cases was insanity noted a month or more after admission.Footnote 20 However, finally, if somewhat grudgingly, it was concluded, that the statistics showed ‘the fact that among the prison population the ratio of insanity arising among persons apparently sane on admission is not less than three times as that amongst the general population of corresponding ages’.Footnote 21 It was also agreed this figure was shaped by the fact that ‘Insanity and crime are “simply morbid branches of the same stock”’ and ‘that they do so dovetail into each other conditions of mental enfeeblement, insanity, and crime’.Footnote 22 This mingling of medical and criminal theories on the nature of the criminal mind, discussed in detail in Chapter 3, can be located time and again in prison medical officers’ discussions on the nature of insanity and weak-mindedness in the prison context from the 1860s onwards.

A number of witnesses presenting to the Gladstone Committee referred to Walker’s excessive workload at Holloway. Dr David Nicolson, then Superintendent at Broadmoor, explained that he had the relative luxury of having between one and two hours to interview and assess a patient, highlighting the contrast with prisons and the pressure faced by prison doctors.Footnote 23 The report also underlined the extensive experience and ability of prison doctors in making difficult judgements on a prisoner’s mental state that required great skill, particularly in cases of murder. Nicolson emphasised that the work was heavy and taxing but that prison medical officers were competent to do it: ‘Everything that one can bring to bear upon it was required, more particularly in the way of approaching and of knowing the individual.’Footnote 24 However, he conceded that prison doctors needed experience of dealing with ‘actual lunatics’, and one of the recommendations of the final report was that evidence of this should be required for prison medical appointments.Footnote 25 The inquiry also revealed the extent to which observation and ‘testing’ still dominated the practices of prison medical officers. Dr Tennyson Patmore, Medical Officer at Wormwood Scrubs, remarked that the detection of delusions might take several visits over several months. He also wished to bring the attention of the committee to the fact that prisons still contained a large population who endeavoured to ‘malinger insanity’ and the duty of the medical officer was to ensure, through long observation, ‘the ends of justice are not defeated by our being taken in by the malingerer’.Footnote 26

Among several witnesses to the Gladstone Committee who had experienced imprisonment, Michael Davitt, Fenian and land reformer, provided extensive evidence. He had served almost nine years of penal servitude in Millbank, Dartmoor and Portland prisons, and had also given evidence to the Kimberley Commission in 1878. Alongside his condemnation of prison discipline, conditions of labour, dietary and medical care, Davitt criticised the nine months of solitary imprisonment and urged it to be abolished or reduced to short periods at the beginning and end of sentences, as it was a horrific experience for first-time offenders, while ‘old lags’ had no fear of it and used it for malingering purposes to avoid hard labour.Footnote 27 ‘I believe that solitude must necessarily tend to injure all minds. To be shut up for 23 hours out of every 24 for nine months, and not allowed to speak except in the instances I have given, is a fearful ordeal for any human being to go through.’Footnote 28 Davitt argued there was a great deal more of insanity and weak-mindedness among prisoners than was recorded in official reports and statistics, and noted a large increase in the incidence especially among prisoners who had been in prison on several occasions.Footnote 29

Irish prisons received less condemnation from the Gladstone Committee and individual English prisons were compared unfavourably with them. Captain Frank Johnston, Governor at Dartmoor Convict Prison, was quizzed on why the death rate at Dartmoor was twice that of Irish prisons and why corporeal punishment, which had not been implemented in Irish convict prisons for over a year, was still used there.Footnote 30 The Prison Commissioner, Robert Sidney Mitford, could not account for the notable differences in rates of punishments and deaths, though it was suggested by the Commissioners that discipline in Irish prisons was enforced less vigorously than in England.Footnote 31 William Murphy has argued that owing to the pressures exerted by political prisoners on Irish prisons, rules and discipline were relaxed somewhat, and in 1889 new regulations gave the General Prisons Board discretion to further ameliorate conditions.Footnote 32 This gradual winding down of the rigour of the discipline coincided with the departure of Bourke as Chair of the General Prisons Board in March 1895.Footnote 33 By that time, the average daily number of prisoners was 2,323, with mentally ill prisoners generally removed swiftly to asylums when necessary. Nonetheless, despite criticism by the 1884 Royal Commission on Irish Prisons of prison medical officers’ failure to acknowledge the high rates of mental disorder among prisoners, prison doctors continued to insist that the prison regime was not at fault. In its Report for 1895, the General Prisons Board, noted that 75 prisoners were transferred to asylums, of whom 61 were reported to be insane on admission, one weak-minded and one ‘doubtful’. Among the remaining twelve prisoners, four were reported sane while in prison, but were found to have been insane at the time when their offences were committed. The Board therefore concluded that only eight prisoners became insane in prison; one became ill three days and another twelve days after committal.Footnote 34 While William Tallack of the Howard Association had little good to say about English prisons, he was more positive about the Irish prison regime. During 1895 he visited a number of Irish prisons and was impressed at the variety of labour and the conditions. He also stressed the excellent results produced in Irish medical departments and the influence of their medical officers. He conceded, however, that the level of mental disorder in Irish prisons was still a concern, with some insane prisoners still retained in prison to save rates; some 82 insane prisoners were admitted in 1893–94, though it was claimed that only eight of these became insane in prison.Footnote 35

The issues of detecting malingerers, prison medical officers’ workload and the nature of insanity and weak-mindedness in prisons were at the core of the work of the 1904 Committee of Inquiry into Doubtful Cases of Insanity Amongst Convicts in Ireland. Originally appointed to assess whether a group of prisoners, transferred from Maryborough Prison to Dundrum Lunatic Asylum, were ‘really insane’ and to agree on a set of principles for prison and asylum medical officers when dealing with such cases, the Committee conducted a detailed review of each case and of the management of weak-minded prisoners at Maryborough Prison. The Report of the Committee emphasised the importance of ‘skilled observers’, whose ‘common sense’ and ‘practical experience’ in ‘individual cases’ helped them detect malingers and prisoners who sought ‘entrance to the haven of asylum life’.Footnote 36 The Committee noted the burden on prison staff of transferring ‘backwards and forwards, from Prison to Asylum, and from Asylum to Prison, of persons of this class … and [the] inconvenience and expenses to the Public Service’. While the number of mentally ill inmates in Irish prisons was not as high as in English prisons, the Committee’s survey of the life-histories of each prisoner under review highlighted the persistence of the problem as significant numbers of the mentally ill were still sent to Irish prisons despite efforts to divert them.Footnote 37

While the Gladstone Report was welcomed as ‘the beginning of a beneficent revolution’, its impact has been questioned, as has its status as a real turning point, though its publication did result in Du Cane’s immediate, albeit reluctant, resignation.Footnote 38 As noted above, in Ireland the full rigour of penal discipline had eased somewhat in response to the demands of political prisoners. The Gladstone Committee recommended individualised treatment to develop prisoners’ moral instincts, to train them in orderly and industrial habits, and to improve their mental and physical health. It also advocated the separation of prisoners into types, including first offenders, habitual prisoners, the feeble-minded and drunkards, to be dealt with by special programmes. And finally it recommended the reform of the separate system, and a renewed emphasis on productive, collective labour and recommended the abolition of penal forms of labour, including the treadwheel and crank. On its recommendations, the Borstal Institution for male juveniles aged between sixteen and twenty-one was established at Rochester in Kent in 1901, and the Committee influenced the opening in 1906 of the Clonmel Borstal in Ireland. As Gladstone’s recommendations were encoded into regulations in England, the rules for Irish prisons were ‘assimilated’ to the English model, with the implementation of a new set of rules for local prisons in 1902.Footnote 39

The Gladstone Committee also rearticulated the expertise of prison medical officers, notably in the detection of malingering and weak-mindedness, and pointed to their ability to understand the relationship between criminality and mental deterioration. It has been regarded as a watershed moment for prison medical officers who were accorded increased authority. Yet, as shown in Chapters 3–5, prison medical officers in England and Ireland had been claiming this particular form of expertise from the 1860s onwards as they sought to navigate the demands of their role as physicians and enforcers of prison discipline. Their expertise was rooted in their ability to deal with mental illness in criminal justice settings, and through the production of new taxonomies that applied in prison contexts. The detection of malingering had been a key part of the prison medical officer’s role from early in the nineteenth century. However, Gladstone reaffirmed the significance of the prison doctor in dealing with mental illness, as well as the substantial part this played in making up their workload. As reformatory aspirations had diminished, the prison medical officer had overtaken chaplains in mediating on matters of the mind.Footnote 40 Though the spiritual revival and individuals such as Reverend Morrison were no doubt important in the build-up to the Gladstone inquiry, the era of the chaplain’s dominance in diagnosing and mediating mental disorder, as outlined in Chapter 2, was long gone by 1895.

Locale, as our study demonstrates, was also a key factor in terms of the particular pressures facing prisons and in relation to the way power was brokered between prison officers and between external organisations and institutions, including magistrates and Boards of Superintendence, visiting committees and local asylums, as was the impact of particular individuals, such as Chaplain James Nugent at Liverpool who continued to push moral agendas designed to reduce the prison’s population and reform its inmates in the final decades of the nineteenth century.Footnote 41 While a number of prison medical officers, notably Dr David Nicolson, forged their identities as specialists in the practice of prison psychiatry in the pages of medical journals, others, such as Dr Robert McDonnell, through their day-to-day work and presentation of evidence via reports and parliamentary inquiries, emphasised the importance of their roles in individual prisons and that they were creating a new form of psychiatry in criminal justice settings.

It was suggested in Chapter 1 that the prison has loomed small in terms of the scholarship on the history of psychiatry, and our book is intended to go some way in developing this area of scholarship, while acknowledging the scope for further comparative inquiries through exploration of different periods and geographical contexts. Our study has demonstrated the ways in which psychiatry expanded its professional influence beyond lunatic asylums into prisons during the nineteenth century, largely in the hands of the prison medical officers who insisted that they were creating new forms of psychiatric knowledge and expertise distinct from psychiatric practice outside the criminal justice system. By the close of the century prison medical officers and asylum superintendents were, however, increasingly working together to tackle the broader issue of the placing of mentally disordered offenders, in a situation hampered by overcrowding and limited resources in both sets of institutions. In many ways the prison and asylum had run along parallel tracks, in terms of sharing a reformist agenda in the mid-nineteenth century, involving control of the prisoner or patient under conditions of enforced confinement and isolation in specially designed environments.Footnote 42 While the purpose of the asylum was to cure its patients, the prison’s mission was to punish and rehabilitate. However, both sought the production of improved and more able individuals, no longer a burden to the state. Both sets of institutions emphasised the critical role of self-management, whether this was under the direction of the chaplains with their efforts at redeeming prisoners in their cells through their admonishments or shaped by the philosophy and practice of moral therapy in asylums, which aimed at self-control and conformity to particular forms of behaviour. It could even be argued that for a brief period in the mid-nineteenth century the prison chaplains were more ambitious than their asylum doctor counterparts, aiming at inner reflection resulting in deep-seated and genuine redemption, whereas moral treatment less actively pursued the identification of the root causes of mental disturbance.Footnote 43 So too the shift to a more penal approach in the 1860s and 1870s, accompanied by interest in establishing the links between mental decline and criminal behaviour was mirrored by the increased influence of theories of degeneration and heredity in late nineteenth-century asylums, as they too faced the problems of overcrowded conditions and huge pressure on resources and staff.Footnote 44 In both contexts, claims to authority rested increasingly on psychiatry’s alliance with degeneration theory, though equally it can be questioned how influential this theory was in practice, as asylums and prisons continued to focus on individual cases of mental deterioration and to acknowledge the impact of environmental factors.Footnote 45

‘We Are Recreating Bedlam’: The Crisis in Prison Mental Health Services

While the Gladstone Report prompted changes in responses to mentally ill prisoners, shaking off the preoccupation with positivist approaches, and opening the door once again to reform, this emphasis was diluted in the years that followed and, as Bailey has so aptly put it, post Gladstone, ‘the pace of progress in humanizing prisons was glacial’.Footnote 46 Today the situation regarding mentally ill people in prison is far from resolved. Indeed as the number of cases of diagnosed mental illness among inmates has soared in recent decades, and, with few alternatives to prison, in some regards their opportunities for effective treatment have deteriorated. Media reports continue to highlight the plight of mentally ill prisoners and the strain they place on overburdened prisons, prompting The Guardian to claim in 2014 that ‘We are recreating Bedlam’.Footnote 47

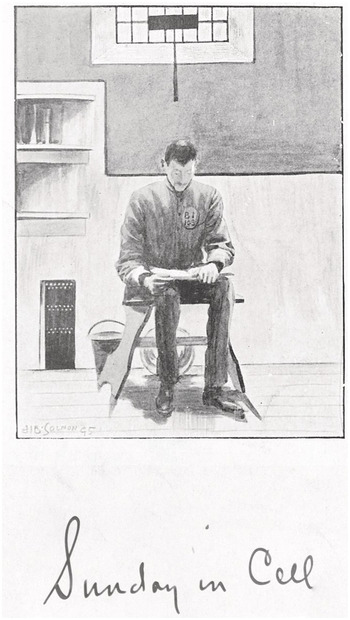

The Gladstone Committee was meant to have swept aside ‘the old-fashioned idea that separate confinement was desirable on the grounds that it enables the prisoner to meditate on his misdeeds’, and, although there were further modifications and the length of separation was reduced for many prisoners in English and Irish prisons, it endured. In 1909 the author and playwright John Galsworthy, reviving earlier campaigns, felt compelled to lobby the Prison Commission and government for its abolition.Footnote 48 In a letter to the Home Secretary, Herbert Gladstone, later reproduced in The Nation, Galsworthy urged ‘the complete abandonment of this closed cellular confinement’.Footnote 49 He described how in the year ending March 1907 1,035 persons, of whom 691 had never been sentenced to penal servitude before, were to endure 4,000-odd hours of ‘agony and demoralisation’, in a ‘smothering process to which the mind must adapt itself or perish’.Footnote 50 Echoing Dickens in 1842, Galsworthy argued that far from causing reflection and sober self-examination, separate confinement led to mental vacuity and put at risk ‘that terribly intricate and hidden thing, the mind’.Footnote 51 Interviewing sixty prisoners at Lewes Prison, which had adapted separation so that convicts worked in roofless cells and could see the warders and prison officers though they could not speak to each other, Galsworthy reported how some were ‘driven crazy’ and complained of sleeplessness. Several men were in tears throughout the interview. The prisoners described how, ‘I didn’t hardly know how to keep myself together. I thought I should go mad’, ‘It made me very nervous, the least thing upsets me’, and ‘It destroys a man’.Footnote 52

Figure 6.1 Sunday in cell, Wormwood Scrubs, c. 1891

Again in 1922, Stephen Hobhouse and Archibald Fenner Brockway’s masterly account English Prisons Today, drawing on their own prison experiences and the recollections of prison staff and inmates, illuminated the endurance of the system of separate confinement, which they defined as one of the greatest flaws in an overall bankrupt prison system, ‘driving the man more and more into himself’.Footnote 53 Political prisoners held in Ireland also highlighted the persistence of separate confinement and harsh prison conditions. While Ernest Blythe noted that the prison regime was not as severe as that endured by the Fenians in the 1860s and 1880s, Herbert Moore Pim, who was held in Belfast Prison with Blythe in 1915, published a polemical prison memoir under the pseudonym A. Newman in which he slated the ‘English jail system’.Footnote 54 An author, Quaker and separatist nationalist, he described prison life as ‘a series of humiliations’ as prisoners were ‘forced night after night to recall with horrible vividness the evils of the past’.Footnote 55 He noted how ‘Men go mad in prison at the end of three months’ and that prison was ‘one mass of preventions against suicide’.Footnote 56 He also commented on the architecture of the prison cell: ‘The oppression of being shut in, and the abominably constructed door, whose every nail seemed to be a symbol declaring the idea of jaildom.’Footnote 57

Toby Seddon has summarised changes in the early twentieth-century prison, and efforts to clear out various categories of mentally ill prisoners, including the weak-minded, in order to focus on ‘responsible prisoners’, capable of reform. He has also highlighted the further shift towards psychological and psychoanalytic approaches in the 1920s and 1930s, with many doctors arguing that all crime had ‘mental origins’. In the post-war period there was a further shift towards penal-welfarism and correctional crime control, though most of this work, as in the nineteenth century, remained diagnostic.Footnote 58 Though, as Chapter 3 illuminated, the weak-minded became the focus of increased concern in the late nineteenth century, efforts to move those thus identified from prison were hampered by the lack of institutional facilities, an early illustration of what was also to become a persistent problem during the twentieth century for the mentally ill. In Liverpool ‘feeble-minded’ prisoners ended up in lunatic asylums and workhouses owing to the absence of services, and, while both prisoners classified as insane or mentally defective were transferred, as in 1917 when eight prisoners were removed to asylums and six to ‘Mental Deficiency Institutions’, demand for places was far from being fully met.Footnote 59 In Ireland there were no separate state-run institutional facilities for ‘feeble-minded’ prisoners established in this period, and these offenders continued to accumulate in prisons, workhouses and lunatic asylums in the early twentieth century.

After World War II, ‘deinstitutionalisation’ saw significant numbers of mentally ill people confined in prison as mental hospitals began to close or reduce provision.Footnote 60 In England, the closure of the large Victorian asylums in the 1960s and 1970s led to a drastic decline in the number of psychiatric hospital beds, and in 1978, J.H. Orr, Director of Prison Medical Services in England, described how

Mentally disordered offenders are entering prisons not because the net is insufficiently wide or discriminating but because hospital places are not forthcoming … we imprison more mentally disordered offenders than under the old Lunacy and Mental Deficiency Acts. In 1931 (when the average prison population was about 12,500) 105 sentenced prisoners were recognized as suffering from mental illness and transferred to hospital. In 1976 the number of sentenced prisoners recognized as suffering from mental illness was more than double this figure, but the number transferred … less than half.Footnote 61

Psychiatric hospitals, meanwhile, were unwilling to take prisoners and lacked suitable facilities and secure units for managing ‘difficult patients’.Footnote 62 At Pentonville in 1959, out of the 4,000 received into the prison, around twenty-four men were referred to the psychiatric unit at Wormwood Scrubs for medical treatment for mental disorders or to psychiatric treatment agencies on release. A similar proportion each year were certified insane. Certification was unpopular with one member of the medical staff at Pentonville who ‘firmly believed that medical superintendents of mental hospitals were very reluctant to receive offenders’, tending to decertify them and send them back to prison as soon as possible.Footnote 63

In Ireland, deinstitutionalisation and the closure of the Victorian asylums occurred at a slower pace, but the provision of psychiatric beds was still under pressure. Consequently, psychiatric hospitals were severely overcrowded. At the same time, the prison estate and prison population remained small until the 1960s, while there were very limited prison psychiatric services. The 1966 Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Mental Illness noted that the transfer of prisoners certified to be ‘insane’ to local psychiatric hospitals was not always suitable and recommended the use of Dundrum for this purpose.Footnote 64 They also proposed that the prison service make appropriate arrangements with relevant local health authorities to provide psychiatric services for prisoners.Footnote 65 Yet, in 1972 most major prisons did not employ psychiatric staff, though Mountjoy Prison’s medical officer was a trained psychiatrist.Footnote 66 Prisons remained heavily dependent for psychiatric services on local hospitals as well as the Central Mental Hospital, Dundrum, which was also operating at full capacity. It took until the 1980s for the recommendation of the 1966 Commission of Inquiry to be implemented, and by then prisoners were only accepted at Dundrum as psychiatric facilities outside prison shrank further. Meanwhile prisons continued to be criticised for failing to provide psychological and psychiatric services.Footnote 67

In 1991 the Home Office published a study by Professor John Gunn on mental health problems in English and Welsh prisons, based on interviews with just over 2,000 prisoners or 5 per cent of the sentenced prison population. Some 37 per cent of men and 56 per cent of women serving sentences of over six months were reported to have a medically identifiable mental health problem. It was estimated that over 9,000 prisoners were suffering from a significant mental disturbance, many of whom were in urgent need of transfer to hospital. At the same time, patients who did not need to be in psychiatric hospitals could not be moved to community facilities because of the shortfall in provision. As a result of this and with mental hospital services in England so lacking, ‘mentally disordered people continue to accumulate in the prison system’.Footnote 68 In England and Wales the number of people in prison continued to rise dramatically, by 25,000 between 1995 and 2005, making many prisons very overcrowded, and prompting one Guardian report to assert that the UK was determined to emulate the US with its conditions of ‘terrifying harshness’.Footnote 69 In 2005 Troubled Inside, a series of reports commissioned by the Prison Reform Trust, concluded that 72 per cent of male and 70 per cent of female sentenced prisoners suffered from two or more mental disorders.Footnote 70

One of the striking features of late twentieth-century Irish prisons has been the build-up of mentally disordered offenders; in 1993 it was estimated that 5 per cent of prisoners in the Republic were mentally ill and there was a waiting list for admission to Dundrum.Footnote 71 Initiatives to improve poor psychiatric provision within prisons included the introduction of in-reach psychiatric teams to prisons in England and Ireland, and a diversion scheme was developed at Cloverhill remand prison in Ireland.Footnote 72 Yet, the problem persisted; in 2018 Michael Donnellan, Director General of the Irish Prison Service, informed a parliamentary committee that 8 per cent of prisoners had a diagnosed psychiatric condition and that managing ‘people with severe and enduring mental illness posed a major challenge’ to the Irish Prison Services. A departmental ‘taskforce’ was appointed to consider the mental health and addiction challenges of persons interacting with the criminal justice system in April 2021.Footnote 73

Meanwhile, prison medical officers and prison medical services have in recent decades become more open and engaged, joining in critiques of the prison medical services and highlighting obstacles to the care of their prisoner patients. In parliamentary inquiries undertaken in the 1980s in the UK, prison medical officers reflected more openness on the issue of dual loyalty and expressed an eagerness to work with the rest of the medical profession.Footnote 74 Duvall has argued that this shift to collaboration began to replace assertions that prison medical officers have some form of particular knowledge and special experience in treating mentally ill prisoners.Footnote 75 Nonetheless, many reports remained critical of their role. Richard Smith described in a series of articles in the British Medical Journal in 1983 the isolation of prison doctors, and, facing pressures of overcrowding, the loss of interest in reform and the role of psychiatric techniques in this process, even though it was acknowledged by mid-century that ‘the greater part of the work lies in the psychiatric field’.Footnote 76 Still referring in 2005 to the crisis in the prison medical service, Gunn, for example, found many doctors excessively preoccupied with the problem of malingering, as well as a huge level of unmet psychiatric need and overuse of psychotropic drugs, while there were fewer opportunities for doctors to keep up with developments in medicine and many struggled to resolve the tension between managerial and physician roles; ‘it is difficult for doctors to separate their responsibility to patients as a doctor from the need to adapt medical care to meet the requirements of the current prison system’.Footnote 77 In England responsibility for commissioning all health care services for prisoners was transferred to the National Health Service in 2013, but still as prison populations continue to grow, so too do the number of people in prison who are reported as having mental health diagnoses, and efforts to achieve an equivalent health service flounder in a situation of general shortfalls in psychiatric services. In Ireland too integration of prison medical services with general health systems remains the goal, and in 2016 Judge Michael Reilly, Inspector of Prisons, produced a report on prison health care that strongly advocated for the incorporation of prison health care into the Irish Health Service Executive.Footnote 78

The residue of the nineteenth-century prison system remains with us today, not only in the physical structures of prison estates in England and Ireland, but also in prison disciplines that still emphasise order and uniformity, and in the imposition of solitary confinement, no longer a philosophy and method of reform, but a form of protection, or means of dealing with disruptive behaviour among prisoners, the poor physical state of prisons, overcrowding and the shortage of prison staff and resources. Many prisoners continue to be confined in restricted regimes spending most of their day in cellular isolation. Some request removal to these restricted regimes, ‘prisons within prisons’, for protection from other violent inmates or to get away from drugs, though they may not be fully aware of the extent of their isolation, and ‘segs’ can become ‘a breeding ground for mental health problems’.Footnote 79

A recent report on Wormwood Scrubs Prison in London revealed that many prisoners had less than two hours a day ‘unlocked’ and all had only forty minutes of outdoor exercise a day, less than the time prescribed at Pentonville in 1842.Footnote 80 Despite the Irish Prison Service’s commitment to reduce solitary confinement and restricted regimes, in April 2017, 430 prisoners were on restricted regimes, defined as a minimum of nineteen hours locked in cells.Footnote 81 In 2001, the study Out of Sight, Out of Mind found that 78 per cent of prisoners in solitary confinement in Irish prisons were mentally ill.Footnote 82 The Irish Penal Reform Trust’s 2018 report on solitary confinement in Irish prisons highlighted the ‘exceptional and devastating harm to prisoners’ mental health that can be caused by extended periods of isolation’, and sought the abolition of ‘the practice of holding any category of prisoner on 22- or 23-hour lock-up’ and that such restrictive regimes should be an implemented as an ‘exceptional measure’.Footnote 83 They noted that the Irish Prison Service anticipated 11 per cent of the prison population would be subject to restricted regimes in the coming years and that designated parts of Mountjoy Male Prison and the Midlands Prison would be classed as ‘protection prisons’. This included a unit at the Midlands Prison for a small number of ‘violent and disruptive’ prisoners, managed jointly by the Prison Psychological Service and the prison’s operational staff.Footnote 84 In the late nineteenth century, as detailed in Chapter 4, violent behaviour on the part of mentally ill prisoners that disrupted prison discipline was likely to trigger removals to lunatic asylums. Nowadays that opportunity rarely exists and forensic hospitals, including Dundrum Central Mental Hospital, operate at full capacity. Prisoners with severe psychiatric conditions, some of whom are violent, suicidal or liable to self-harm, are inappropriately retained in prisons in Safety Observation Cells, a practice criticised by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture during an inspection of Irish prisons in 2015.Footnote 85

While there is no question that in many regards conditions have improved, and that prison psychiatry and the intention to treat and care for mentally ill prisoners effectively has moved on considerably, some prisons remain desperately overcrowded, resources are scarce and psychiatric support limited both within and outside prisons. People in prison had and still have higher rates of mental illness than the general population, those with mental health problem are more likely to be admitted to prison, and prisons exacerbate mental health problems. The Irish Penal Reform Trust report extensively referenced Deep Custody, produced by the English Prison Reform Trust in 2015, which also highlighted the toxic effects of segregation, ‘social isolation, reduced sensory input/enforced idleness and increased control of prisoners’.Footnote 86 The findings of the report and particularly the responses of prisoners subjected to isolation, echo and reproduce the observations of prison authors in the late nineteenth century, and those collected by John Galsworthy at Lewes Prison in 1909, with the prisoners he spoke to describing how the ‘Walls seem to close in.… I get blankness in the brain – have to stop reading’, ‘Its hell upon earth’, and ‘Almost unbearable depression’.Footnote 87 In a similar way the prisoners interviewed for the report Deep Custody explained ‘The longer you’re here, the more you develop disorders. Being in such a small space has such an effect on your social skills.… Its isolation to an extreme’, ‘All my mental health problems start kicking in – been really depressed listening to all the voices a lot more, just stuck in my thoughts’ and ‘Your head does go … only so many times you can speak to four walls’.Footnote 88