The seclusion of the cell, depriving the prisoner of associations which divert the mind, leaves him to reflect upon his privations, and thus increases their severity. The Separate System at least satisfies, more than any other mode of imprisonment, this primary requirement of a sound penal discipline; – it is severe.Footnote 1

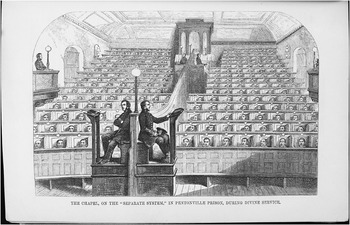

In 1852 Reverend John Burt, Deputy Chaplain at Pentonville ‘Model’ Prison, London, published a vigorous and lengthy defence of the separate system of confinement, the disciplinary regime introduced to the prison when it opened in 1842. Inspired by the ‘Philadelphia’ system, Pentonville’s 500 convicts worked, slept and ate in single cells, were separated from fellow convicts when at exercise and chapel, and were forbidden from communicating with each other at all times. The ‘Model Prison’ became emblematic of the most stringent and pure form of separate confinement and would be an inspiration to a future generation of prison architects and administrators, and the example for many prisons, including Ireland’s model convict prison, Mountjoy, which opened in Dublin in 1850.

While Burt acknowledged that ‘Pressure upon the mind under a Cellular System is a necessary concomitant of its characteristic excellence’, his 1852 publication was largely a response to the mounting criticism and growing evidence that the regime at Pentonville was detrimental to the minds and mental wellbeing of prisoners.Footnote 2 By the 1850s, this criticism had resulted in modifications to the separate system at Pentonville though not the rejection of separate cellular confinement itself. Burt insisted that the minds of prisoners were protected at Pentonville through daily contact with prison personnel, notably prison chaplains and schoolmasters, contact largely absent in the disciplinary regimes devised at other prisons in America and England. ‘Separation’ at Pentonville, he asserted, ‘was not solitude’.Footnote 3 Yet by 1852 Pentonville’s engagement in a ten-year ‘experiment’ with the most rigorous form of separate confinement introduced to any of the ‘modern’ prisons of nineteenth-century England and Ireland was steadily being wound down. Some forty-four prisoners had been moved out of the separate system at the prison owing to concerns about their mental health, and seven were removed from Pentonville on ‘mental grounds’ as ‘unfit for separate confinement’.Footnote 4 After 1847 Pentonville’s Commissioners set about introducing a series of modifications to the disciplinary regime – principally by reducing the time spent in seclusion – in an attempt to alleviate its full rigour, and by the 1850s Pentonville was deemed a flawed experiment in prison discipline.

As Burt was pursuing his defence of separate confinement at Pentonville and of the system’s key advocates, William Crawford and Reverend William Whitworth Russell, the regime was being introduced to prisons across England and Ireland and it would dominate prison regimes until the early twentieth century. Separation had been enshrined in the 1779 Penitentiary Act and was implemented in various forms by Sir George Onesiphorus Paul at Gloucester Prison in the 1790s, at Millbank Penitentiary in London, set up in 1816, and at Richmond General Penitentiary, Dublin, opened in 1820. The Prisons Acts of 1839 (England) and 1840 (Ireland) regularised its use in local gaols and houses of correction, enabling prison inspectors to certify prison cells fit for separate confinement. However, it was during the 1850s that the modified Pentonville version of the separate system would become embedded in prison regimes as a central tenet of discipline and organisation in convict prisons, gaols and houses of correction, as purpose-built and older institutions were adapted for its introduction.Footnote 5 This followed the recommendations of several parliamentary inquiries into prison discipline in England and Ireland, and lobbying by prison inspectors, commissioners and penal reformers. Support for the modified version of the separate system was further reinforced and reinvigorated in the 1860s, as will be explored in Chapter 3, when there was a shift from the emphasis on reform to the discipline’s penal benefits. Yet, time and again, reports of heightened instances of mental distress and disorder among prisoners accompanied the rolling out of the separate system across the two prison estates. In response, prison governors, chaplains and medical officers, as well as alienists working outside the criminal justice system, debated its impact on the mind, questioning how far separate confinement was implicated in the many cases of delusions, mania, self-harm and attempted suicide among prisoners.

The separate system, as implemented at Pentonville, emerged after decades of deliberation on the most effective means of punishing and reforming criminal behaviour through secondary punishment in houses of correction and gaols and transportation to the American colonies. From the late eighteenth century, coinciding with the disruption to transportation caused by the American Revolutionary War in the 1770s, penal and social reformers, including John Howard, Elizabeth Fry, James Neild and Sir Jeremiah Fitzpatrick, as well as bodies such as the Association for the Improvement of Prisons and Prison Discipline in Ireland, criticised the systematic abuse and the appalling hygiene and standard of medical care in gaols and bridewells throughout Britain and Ireland.Footnote 6 They sought the complete reform of prisons and of punishment regimes based on uniformity of treatment and well-ordered prison environments, an ambition that persisted beyond the revival of transportation in the late 1780s.Footnote 7

The plight of the insane in prisons was highlighted from the earliest stages of these campaigns; in 1777 Howard drew attention to the dire conditions in which ‘lunatics’ were held at bridewells, where they were denied treatment and languished in overcrowded and insanitary conditions, disturbing and alarming the other prisoners.Footnote 8 While advocating for prison reform in Ireland during the 1780s, Fitzpatrick, physician and first Inspector General of Prisons in Ireland, urged the removal of insane prisoners to hospitals.Footnote 9 Regarding the nature of the criminal mind, in 1830 Jeremy Bentham argued that criminal offenders were a race apart from other people – their ‘minds are weak and disordered’.Footnote 10 In terms of the practicalities of their management, he suggested that they should not be left to themselves but needed close supervision, restraint and ‘unremitted inspection’.Footnote 11

Much has been written about the early history of prison reform in England, far less on Ireland. Nonetheless, historians have mapped the spiritual and philosophical roots of the separate system of confinement and of the ‘rival’ silent system, the most influential regimes of the early nineteenth century, identifying their transnational nature and the intellectual links between British, Irish and American penal reformers.Footnote 12 Throughout the eighteenth century, social commentators in England, including the novelist and dramatist Henry Fielding, promoted the introduction of different forms of separation to prisons for offenders awaiting trial, and Jonas Hanway, philanthropist and founder of the London Foundling Hospital, was among the first to propose separation for offenders under sentence in a purpose-built institution. His proposals strongly influenced John Howard’s theories on prison discipline.Footnote 13 While the 1779 Penitentiary Act allowed for separation in purpose-built gaols and houses of correction, in practice it was rarely implemented, the most notable exception being the prison opened by Sir George Onesiphorus Paul in Gloucester, discussed below.

Despite early support among prison reformers for separation and cellular confinement, the most effective form of prison discipline was still being debated in the 1830s, shaped by new experiments with modes of imprisonment in America.Footnote 14 These exchanges largely focused on the ‘Philadelphian’ separate system, which attracted powerful support in Britain and Ireland over the rival silent system. Both systems supported the redeeming effects of solitude, yet while separation prevented communication and the spread of information among prisoners, largely through its architecture, the silent system enforced solitude and classification through punishment and discipline. Although the silent system was implemented in many prisons in America, by the 1840s separation had emerged as the clear winner in Britain and Ireland.Footnote 15

A persistent feature of the debates among penologists and prison reformers, including vocal critics of the separate system, was the accusation that the new disciplinary regime of separate confinement was implicated in high incidences of mental disorder among prisoners. Michael Ignatieff and Ursula Henriques have examined concerns about outbreaks of mental distress at Pentonville when it first opened in 1842, implementing the purest and most rigorous form of separation.Footnote 16 Yet, there has been no sustained and detailed exploration of the relationship between the separate system as it was rolled out in local gaols, houses of correction and convict prison systems throughout the 1850s and 1860s and rates of mental breakdown among prisoners.Footnote 17

This chapter explores this association, arguing that the incidence of mental distress and disorder in local gaols and convict prisons was much higher than was officially acknowledged and that the separate system was regarded by many commentators as a contributing factor, if not the primary cause, of high rates of mental illness. The 1850s and 1860s saw vigorous debates on the question of how far disciplinary regimes in prisons prompted or exacerbated existing mental disorders among prisoners or whether criminals were inherently mentally weak and thus particularly vulnerable to mental collapse. Such exchanges took place in official reports and correspondence as well as in the books and articles produced by prison officials, including chaplains and doctors. The chapter also examines modifications to the system of separate confinement after the late 1840s that were shaped largely by this mounting criticism. As discussed below, the most rigorous forms of separation, introduced at Pentonville and adopted two years later in 1844 at Reading Gaol and in 1845 at Belfast House of Correction, were quickly modified. Yet the system endured and there was support for its introduction to local gaols in the 1850s. While local institutions did not always adhere to the separate system in full and its application in individual county gaols and houses of correction varied considerably, many, including larger city gaols, such Liverpool Borough Gaol, endeavoured to implement it as fully as possible.Footnote 18 As discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3, despite mounting evidence that the separate system damaged the minds of prisoners, support for the regime became even more entrenched in the 1860s and 1870s amid heightened anxieties triggered by reports of increased rates of criminality, recidivism and prison committals.

In addition to examining high-level debates and inquiries into penal policy, this chapter interrogates the ways in which mental disorder was reported, deliberated on and managed in Irish and English prisons, with Irish prisons and some English ones producing modifications to the system at a very early stage, intended to mitigate the impact of prison discipline on the mind. It explores how prison staff, medical and otherwise, assessed the mental health of prisoners and the management of mental breakdown for both male and female prisoners. While at Pentonville and several other prisons experimenting with separate confinement in the 1830s and 1840s the chaplain to a large extent assumed responsibility for managing the minds of prisoners, after the 1850s prison medical officers increasingly asserted their expertise in identifying cases of mental illness among prisoners, and, as discussed in Chapter 5, in distinguishing feigners and malingerers from ‘true’ cases of insanity. Permeating debates on how far the system of separate confinement provoked mental distress and discussions on how to manage this, was the issue of ‘damage limitation’, as criticism of disciplinary structures, philosophies and arrangements for the management of mental disorder implied that there was something fundamentally wrong with the new system of prison discipline. Central prison administrators and prison officers had a vested interest in presenting the new system in a positive light, and those urging this particular brand of reform were keen to downplay the impact of separation on mental wellbeing. As this chapter demonstrates, some acknowledged the links between high rates of mental distress and the extreme rigour and taxing nature of the system of separate confinement, while others dismissed such connections and defended their institutional practices. Certain prisoners, as discussed in Chapter 4, were transferred to criminal or local lunatic asylums, often after long delays and lengthy deliberation among prison staff regarding their mental state. Others were sent to prison hospitals, confined to isolation cells, transferred to other institutions within the prison estate or discharged, and many were repeatedly punished for their disruptive behaviour in prison.

Rival Prison Regimes: The Silent and Separate Systems

Reflecting on the variety of prison disciplinary regimes, Hanway observed in 1776 that ‘Everyone has a plan and a favourite system’.Footnote 19 Fundamental to debates on competing systems was the tension between the legitimate punishment of prisoners and imposition of the ‘debt’ owed to society, and the state’s obligation to provide appropriate standards of care, even at a time when deprivation and poor living standards were the normal experience.Footnote 20 In his 1784 pamphlet, An Essay on Gaol Abuses, Sir Jeremiah Fitzpatrick observed:

the primary idea of prison is keeping the criminal in safe custody to answer to the state whose laws he has transgressed; humanity tells us the secondary idea is to harrow up his soul with the thoughts of future punishment and so render him penitent; and how can this be so effectively obtained as by keeping his body in good health on which depends the exquisiteness of that sensibility, which will awake in him the proper degree of alarm so necessary to his situation.Footnote 21

Reformers, influenced by a combination of evangelicalism, Benthamite utilitarianism, and humane and practical concerns, sought to develop refined forms of punishment and work regimes. While evangelicals strove for the salvation of sinners by urging the spiritual and moral reform of prisoners, utilitarians looked for industrious convicts who could support themselves and the prisons through work.Footnote 22 Nearly all agreed that unchecked association among prisoners promoted moral contamination, and various forms of separation of prisoners on the grounds of sex and longevity of criminal career were advocated. Each regime incorporated periods of spiritual reflection and religious exhortation. The Gloucestershire magistrate, Sir George Onesiphorus Paul, for example, introduced a regime of complete separation similar to separate confinement in his county gaol as early as 1791.Footnote 23 There, prisoners confined in single cells worked and reflected on religious tracts, benefited from the spiritual guidance provided by the chaplains, and endured punitive treadwheel exercise and a low diet. Preston Goal, even before the arrival of its influential chaplain, Reverend John Clay, took a prominent role in shaping national penal policy, its keeper James Liddell introducing a profitable labour system working with local textile firms.Footnote 24 The Inspector General of Prisons in Ireland, Fitzpatrick, favoured ‘solitude, silence, labour and simple, cooling fare’ as ‘the effectual treatment’; although inspired by the work of Howard, he placed less emphasis on religious exhortations, and his pamphlet was largely shaped by medical and scientific principles.Footnote 25 While welcoming the contribution that convicts’ industrial labour made to the cost of running gaols and prisons, Fitzpatrick opposed associated labour in prison, arguing that ‘labour, with reflection on its useful consequences, would occupy the baneful vacuity of the mind’. ‘Solitude would naturally soften the obdurate and lead to discoveries whilst corruption would from a want of evil communication naturally cease.’Footnote 26 He implemented a version of this regime at St James’s Street Penitentiary, Dublin, when it opened for juveniles in 1790.Footnote 27

By the early nineteenth century, spiritual reformers, who promoted complete separation and the centrality of reflection and prayer, had become influential, particularly within English government circles. Campaigners and prison officials who supported labour regimes were increasingly sidelined and their approach criticised for distracting prisoners from the spiritual reflection essential for reform. The infamous treadwheel was installed in prisons across England and Ireland in the early nineteenth century.Footnote 28 While in the Lancashire prisons, the power it produced was used for manufacturing purposes, elsewhere the treadwheel was employed as a form of punishment, and it, along with other forms of futile work, replaced profitable and productive labour. An 1819 Select Committee praised Liddell’s work at Preston that combined kindness with productive employment, but commented that ‘religious care and instruction was wanting’, opening the door to the appointment of John Clay as chaplain in 1823.Footnote 29

In Ireland, support for profitable labour endured, notably among the two recently appointed Inspectors General of Prisons, James Palmer and Benjamin B. Woodward, who suggested linking the treadwheel ‘to machinery connected with profitable manufacture’ such as ‘raising water and scotching flax’.Footnote 30 Hard labour, including stone breaking, they argued, was not only economical but also acted as a deterrent and guarded against ‘making gaols too desirable’.Footnote 31 The Inspectors, however, insisted that profit from prisoners’ labour was not the ‘primary object’ at the Richmond General Penitentiary, Dublin. Designed by the architect Francis Johnston, modelled on Millbank and centrally administrated, it was established as the ‘flagship’ experiment with the separate system of confinement and penitentiaries in Ireland. Richmond was intended for convicts aged between eighteen and thirty years, whose sentences for transportation were less than seven years, and reformation of the prisoners and training in a profitable trade was to be prioritised over punishment.Footnote 32 Richmond received its first convicts in 1820, and with the appointment of Governor William Rowan in 1823, the Inspectors were optimistic about its success. The penitentiary, however, soon became embroiled in a scandal over allegations of proselytism and conversions secured through torture, resulting in an official inquiry in 1826; its status as an exemplar of penal reform never recovered.Footnote 33

By the 1830s theorists of prison discipline fell into two main camps, advocating for the silent or the separate system.Footnote 34 The renewed interest in separation and the inspiration for the version of the separate system introduced to English and Irish prisons came from the Eastern State Penitentiary, Philadelphia, where it was first implemented in 1829. Shaped by the ideas of early reformists, such as Hanway, and in America by a group of, largely Quaker, social reformers, led by the influential physician, Benjamin Rush, the Philadelphian regime was meticulously planned and implemented. Designed to be challenging for prisoners, inmates had little or no contact with other prisoners or staff, were to reflect upon their crimes and be urged towards repentance and reform.Footnote 35 Prisoners on life sentences were confined in basic solitary cells, with provision for ventilation, heating and sanitation, for three years, sometimes more, emerging only for exercise in separate yards or for attendance at religious service in partitioned chapels.Footnote 36 While prisons designed for separation were more expensive to build – Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon was the inspiration for John Haviland’s radial plan for Eastern State Penitentiary – once opened they were less costly to run than the rival ‘silent’ system.Footnote 37 The silent system was associated with the Auburn and Sing Sing Penitentiaries in New York State where communication among prisoners was prohibited at all stages of their sentences. Though prisoners worked and dined in association, strict silence was rigorously enforced through harsh punishments. The system placed greater emphasis on instilling work habits among prisoners; advocates sought to bend prisoners to rules and regulations and were less optimistic as to their potential for reform.Footnote 38 The strengths and weaknesses of the two models were vigorously and publicly debated in the British and American press and in publications produced by their advocates. Visits to Eastern State, Auburn and Sing Sing also formed an essential part of the itinerary of early nineteenth-century European prison reformers interested in devising effective regimes for punishment and reformation. These regimes, they believed, would end the dreaded scourge of ‘moral’ contamination rife among prisoners confined in older gaols and bridewells, and provide the means for the true reformation of prisoners’ minds and bodies in a suitably punitive environment.

Both systems attracted ardent and influential supporters among prison officials in England, though the silent system did not garner much official support in Ireland. George Laval Chesterton, Governor of Coldbath Fields House of Correction in Middlesex from 1829 to 1854, was a strong advocate of the silent system and a close friend of Charles Dickens, an equally outspoken critic of the separate system. Chesterton imposed the silent system comprehensively at Coldbath Fields, then the largest prison in Britain.Footnote 39 Convinced that most criminals were habitual, vicious and unreformable, he dismissed the separate system as ‘doctrinaire sentimentality’, which subjected prisoners to ‘direful torture’ and ‘mental depression’.Footnote 40 Any signs of remorse or reformation among prisoners under that regime, he insisted, were temporary and once released, they would return to their previous habits.Footnote 41 Though the regime at Coldbath Fields was severe, Chesterton described the system at Eastern State as ‘signally inhuman’, lamenting the ‘protracted sufferings of the miserable beings exposed to such refined torture’.Footnote 42 He also criticised its supporters for failing to acknowledge the ‘mental depression’ and agitation it caused prisoners whose mental states deteriorated while confined.Footnote 43 At Coldbath Fields, while prisoners were confined in separation in cells for long periods during the day, allowing for spiritual reflection, this was combined with associated labour, which permitted limited contact among prisoners. Despite the unheated cells and punishing work tasks, Chesterton’s prisoners were reported to be healthier and rates of lunacy low compared with other prisons and even the national rate.Footnote 44

The rival system of separate confinement, however, had persuasive advocates, and the most fervent of these were prison chaplains who envisaged for themselves an important role as spiritual guides and reformers. These included Reverend John Clay, a national authority on crime and punishment and prison chaplain at Preston Gaol from 1823. There he urged separation, though he permitted congregated schooling, worship and exercise. He also underlined the importance of religious services and spent upwards of six hours a day visiting prisoners in their cells. He saw crime as a moral failing and moral self-help, stimulated by religion and education, as a means of reform.Footnote 45 William Crawford and William Whitworth Russell were particularly influential in driving through the Pentonville experiment, with its forceful form of separation and key role for its chaplains. Crawford was a founder in 1815 of the Evangelical Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline and the Reformation of Juvenile Offenders, an organisation that fostered connections with members of the political and social elites with the purpose of advancing a radical critique of prison conditions.Footnote 46 The Irish Inspectors General of Prisons quoted from the Society’s reports while lobbying local governors and prison officials to implement prison reform in 1824, and the Association for the Improvement of Prisons and Prison Discipline in Ireland imitated its approach and principals.Footnote 47 Through his political links, Crawford obtained a commission from Home Secretary Sir James Graham to visit America in 1833 to report on the separate and the silent systems, with a view to recommending a suitable system for English prisons. Following his visit to Eastern State, Crawford became enthralled by the separate system, which combined a prolonged cellular system of separation with a limited number of cell visitations from reformatory prison personnel. Describing solitary imprisonment as ‘exemplary’ and remarking on the ‘mild and subdued spirit’ of the prisoners, during his visit Crawford also investigated four cases of insanity and one of idiocy at the prison. After consulting the prison surgeon, he concluded that the prisoners were suffering from mental disorders when committed, thereby excusing the regime from responsibility. He remarked too on the failure of Eastern State to appoint salaried chaplains and to instruct the convicts, ‘vital defects which can alone be remedied by the appointment of a resident clergyman who shall not only regularly perform divine service on the Sunday but devote himself daily to the visiting of the prisoners from cell to cell’.Footnote 48 Crawford criticised other systems, including the silent system, for allowing criminals to associate, which, he claimed, made it impossible to prevent moral contamination. On Crawford’s return to England, William Whitworth Russell, chaplain to Millbank Penitentiary, joined him in his support of separation.Footnote 49

Early experiments with separation, however, met with failure in both England and Ireland. Disquiet was expressed concerning the regime at Richmond General Penitentiary, Dublin soon after its establishment. Centrally governed, Richmond was intended for convicts sentenced to transportation or pardoned on condition that they emigrate to the colonies. The appointment of Governor William Rowan in 1823 resulted in a more rigorous implementation of separate confinement, based on a long ‘course of industry, reflection, and instruction’.Footnote 50 Prisoners of both sexes were placed in separate confinement, and divided into three classes, progressing to first class with good behaviour. By 1826, however, ten recently released Roman Catholic convicts alleged that seventeen prisoners had been subjected to cruelties, punishments, deprivations and tortures to induce them to convert to Protestantism.Footnote 51 The subsequent inquiry into these allegations, conducted by the Inspectors General of Prisons and chaired by the law officer, John Sealy Townsend, was expanded to investigate other allegations of cruelty. While the commission of inquiry concluded in 1826 that torture had not been used, wholesale conversions to Protestantism were uncovered and many staff members, including the governor, were described as ‘fanatical’ evangelicals swept up in the Anglican ‘second reformation’ and the Methodist revival then sweeping across Ireland.Footnote 52 George Keppell, an ex-penitentiary officer, asserted that the ‘irritation of the mind’, experienced by the prisoners under punishment, had prompted their conversions.Footnote 53 The experiment with separation at Richmond was slowly abandoned. In the 1830s the prison was transferred to the city of Dublin and catered for untried prisoners, and by the early 1830s the building had been incorporated into Richmond Lunatic Asylum.Footnote 54

Millbank Prison became the site of a further experiment in separate confinement when it opened in 1816. Based partly on Bentham’s panoptical design, it housed up to 1,000 prisoners of both sexes, and, prior to the opening of Pentonville, was England’s flagship penal institution. Costing £458,000 to build, it was the only prison administered by central government.Footnote 55 Concerns were soon expressed about the rigour of the prison regime, and the 1823 Select Committee into conditions at the penitentiary recommended modifications to prevent physical and mental illnesses among prisoners.Footnote 56 However, William Whitworth Russell, who became chaplain at Millbank in 1830, moved the prison’s discipline further towards the cellular system of separation and was noted for his enthusiasm for religious sermons and exhortations as a means of prompting reflection and reformation.Footnote 57 Russell was highly influential at Millbank and his authority was second only to the governor. During his tenure there, Russell provided persuasive evidence on the benefits of cellular confinement to Select Committees on prison reform in 1831 and, along with Crawford, was appointed Prison Inspector for London in 1835. As Inspectors, though their powers of enforcement were limited, they wielded considerable influence – essentially devising national prison policy – until their deaths in 1847.Footnote 58

The support of Russell and Crawford for separation met with fierce criticism, much of which focused on the damage to the minds of prisoners. Two Lord Chancellors, Lord Brougham and Lord Lyndhurst, opposed separation, Lyndhurst describing it as ‘harsh, unnecessary and severe’.Footnote 59 In his travelogue American Notes, published in 1842 following a trip to North America, Charles Dickens famously condemned the separate system at the Eastern State Penitentiary. He wrote of the ‘immense amount of torture and agony which this dreadful punishment prolonged for years inflicts upon the sufferers’. ‘No man has a right to inflict upon his fellow creature … this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain,’ which Dickens held to be ‘immeasurably worse than any torture of the body’.Footnote 60 The American Prison Discipline Society was also vocal in its criticism of the Eastern State Penitentiary and separate system for causing mental breakdown among prisoners. In the Society’s 1838 report they described the effects of the Pennsylvania system on the minds of inmates, arguing that isolation increased rates of mortality and insanity at the institution. They continued to criticise the system in The Journal of Prison Discipline and Philanthropy throughout the 1830s.Footnote 61 In England, The Times took up the cause against the introduction of the separate system, publishing a number of critical editorials and in 1841 Peter Laurie, President of Bethlem Hospital, cautioned:

Immure such a being for a lengthened period in solitary confinement, isolate him … and you will find him the most helpless and resourceless wretch within himself that ever crawled, without energy to look forward, or courage to look back; with no mind to reason, or head or heart to support him, seeing only in the recesses of his own guilty mind and heart a dreary and dreadful void … Misery will follow the want of excitement, melancholy will give place to despair, and if not relieved by contact with living beings, madness or idiocy must follow.Footnote 62

Before Pentonville opened in 1842, specific allegations were also levelled at the regime at Millbank. Following the departure of Russell from Millbank, his successor, Reverend Daniel Nihil, who acted as both governor and chaplain, had strictly enforced a system of separation and intense spiritual reflection at the prison, which antagonised prison staff who were required to transform themselves into ‘religious missionaries’. When he introduced stricter regulations to prevent communication between inmates, reports of prisoners presenting with delusions, mania and insanity increased. Nihil’s regime was investigated and consequently relaxed; by 1840 the period in separation was reduced to the first three months of each sentence. The governor and managing committee resigned in the following year and the prison was converted into a depot for transportation to Australia.Footnote 63

Such evidence had little impact on Russell and Crawford whose commitment to the separate system was unshakeable. After their appointment as prison inspectors, they continued to attack ‘unsuitable’ practices in penal institutions and to publicly criticise local officials. They became instruments of a more decisive intervention from the Home Office in local prison affairs, shaping national penal policy and new prison rules, as well as the 1839 Prisons Act, which provided the statutory basis for the separate system of confinement in England.Footnote 64 From this position, they were decisive in shaping the ‘Model Prison’ and disciplinary regime introduced at Pentonville.

The isolation of the prisoner, ‘to force him to reflection, and thereby to produce a beneficial effect upon his mind’, had been the aim of the Irish Inspectors General of Prisons for several decades, and the movement towards the ‘new era of prison discipline’ of separate confinement gained fresh momentum in the 1840s.Footnote 65 Reflecting on separate confinement and the silent system in 1839, while dismissing other regimes, Majors Palmer and Woodward concluded ‘the advantages of the “Separate,” above any other system of Prison discipline, is clearly Proved’.Footnote 66 In 1840, legislation was passed which permitted confining prisoners in separation, for whole or part of their sentence, in cells approved as suitable. This was followed, in 1841, by the appointment as Prison Inspector of Dr Francis White who replaced the recently deceased Woodward.Footnote 67 White also took on responsibility for inspecting lunatic asylums, and later became the first Inspector of Lunacy in 1843. In their first joint report on prisons, White and Palmer reflected on the progress of separate confinement in Irish prisons, noting some earlier ambivalence about the regime:

the then Inspectors General of Prisons, had some doubts as to the expediency of the system being adopted at once, without some checks and protection being first established against the possibility of its degenerating into anything like cruelty, from the want of sufficient guards and inspection, or into injury to the health of individuals, from too continued a confinement, unless accompanied by constant employment, the use of books, and frequent intercourse with officers or visitors, not Prisoners.Footnote 68

Lacking statutory powers to compel local Grand Juries and prison boards of superintendence to implement separation, they invoked ‘soft power’ to encourage its introduction as a form of ‘experiment’ to try ‘its effects, previous to recommending so large an outlay as altering the entire Prison would cost’.Footnote 69 While White and Palmer reported favourably on new purpose-built prisons, such as that in Belfast, County Antrim, designed by the architect Charles Lanyon on the Pentonville model and containing over 300 cells, and on a small number of county gaols that had been adapted for separation, including the County Gaol at Wicklow, in most prisons separation was not provided for.Footnote 70 Dublin’s city and county prisons, including Newgate and Kilmainham, were robustly criticised for their poor conditions.Footnote 71 During his visit to Newgate in 1841, White found:

a wretched maniac, who was locked up in one of these vaults every night, and left to lie by himself, without light or fire, on a miserable bed upon the floor.… Humanity shudders at the contemplation of such suffering, and a state of things so much opposed to the principles of reason and religion ought to be immediately altered. Upon my representation this poor lunatic was allowed to sleep in a better description of cell.Footnote 72

Describing the ‘progress of prison discipline’ as ‘a science of slow growth’, in their report for 1842 White and Palmer recorded little advance in their experiment with separate confinement in Irish prisons. They blamed this on the Grand Juries’ reluctance to incur the costs of adapting existing prisons or constructing purpose-built institutions for the implementation of separation.Footnote 73

The Belfast Grand Jury, however, was accorded lavish praise by White and Palmer for their support for the construction of a new House of Correction at Belfast, which they anticipated would become a ‘Model Prison for Ireland’.Footnote 74 White, much more so than Palmer, was a strong advocate of separate confinement in prisons and keen to differentiate the regime from the ‘continuous solitary confinement that led to such disastrous results when first tried in America’.Footnote 75 Lanyon, the county surveyor and architect, visited Pentonville when planning Belfast House of Correction, which received its first prisoners in 1845.Footnote 76 The prison had 320 single cells over four wings, two for males with three stories and two for the female prisoners with two stories.Footnote 77 Separation was implemented throughout, including in the chapel, which was divided into stalls, and at exercise and outdoor labour. Prisoners wore peaked caps to disguise their features while moving through the building.Footnote 78 There were three chaplains appointed to the prison: the Episcopalian Chaplain, Allen; Presbyterian Chaplain, Shaw; and the Roman Catholic Chaplain, McLoghlen.Footnote 79

Meanwhile, in 1843, the Inspectors sought financial support for building in Dublin ‘a Model Convict Prison, as in London, such as would permanently improve the habits of the convicts, and be an example to our county gaols, on a better site with ample accommodation’.Footnote 80 They repeated these pleas for a ‘national model prison’ in subsequent annual reports and, while praising the Grand Jury and Board of Superintendence at Belfast Gaol, in 1845 they concluded that a ‘perfect trial’ of the system had yet to be completed.Footnote 81 Despite the Inspectors’ commitment, the establishment of a system of convict prisons in Ireland with a model prison based on the separate system at its heart was delayed for some years. The catastrophic impact of the Great Famine (1845–52) swelled the populations of local gaols and convict prisons, and, even though the numbers transported rose during the crisis, government convicts awaiting transportation steadily accumulated, placing the prison system under severe pressure. In 1845 there were 627 government convicts in custody; by 1849 the number had reached nearly 4,000.Footnote 82 Home Secretary Sir James Graham was apprised of the accommodation crisis, and the Board of Works in Ireland entered negotiations for the purchase of a site for a new prison. However, by July 1846 building work had not commenced.Footnote 83 Instead, the existing prison infrastructure was expanded and repurposed; in 1847 Spike Island barracks in Cork was converted into a convict prison for 600 inmates and Philipstown barracks in King’s County was fitted up in 1845, while older gaols in Dublin were converted into convict depots in the 1840s.Footnote 84 A ‘Model Prison’ in Dublin, underpinned by an ideological commitment to separation, was belatedly opened in 1850.

Model Prisons and the Mind

It was above all Pentonville Model Prison, admitting its first prisoners in 1842, that embodied a decisive shift towards the separate system. Crawford and Russell, along with Pentonville’s Board of eleven Commissioners, including two physician members, Dr Benjamin Brodie and Dr Robert Ferguson, and Joshua Jebb, Surveyor-General of Prisons and Pentonville’s architect, closely supervised the construction and management of the prison and the appointment of senior staff, the governor, chaplains, schoolmasters and medical officers. In his role as Surveyor-General of Prisons, Jebb became very influential in the design and oversight of prisons on the separate system, though he would also develop reservations about the regime. Remarking in 1850 that ‘separation is the only basis on which the discipline of a prison can exist’, Jebb also expressed concern that any improvement among prisoners under separation would dissipate when their period of separate confinement ended, and he remained committed to emphasising the role of labour as crucial aspect of prison discipline that promoted the wellbeing of prisoners.Footnote 85

The Pentonville ‘experiment’ was intended to be exacting and punitive, to break the prisoner down through complete solitude in the prison cell where ‘he will be disposed to self communication, for he has no companion but his own thoughts’.Footnote 86 At the same time, it was designed to produce thoroughgoing penitence and reform in a process led by the chaplains, chiefly through their individual cell visitations. Crawford and Russell carefully identified convicts suitable for the regime, which after eighteen months’ probation would conclude in transportation and a new life in Australia; they were to be first offenders, physically and mentally healthy, and aged between eighteen and thirty-five years, able to withstand the taxing regime and benefit from reform. As Sir James Graham commented, ‘Pentonville shall be for adults what Parkhurst now is for juvenile offenders – a prison of instruction and of probation, rather than a gaol of oppressive punishment.’Footnote 87 Parkhurst, a project also led by Crawford and Russell, had opened in 1838, with solitary confinement for a period of four months forming the cornerstone of its discipline, ‘affording’, as Jebb reflected in 1858, ‘time for reflection, and securing much amelioration in the feelings and disposition of the boys’.Footnote 88

Incarceration at Pentonville and the period of probation, was to be first in a system of staged punishments decreasing in rigour with each consecutive step, with future conditions following transportation to Australia contingent on convicts’ behaviour at Pentonville; an exemplary record could culminate in a complete pardon.Footnote 89 Solitude and separation was rigorously imposed at Pentonville; convicts worked, ate and slept while confined to their cells for twenty-three hours per day. All communication was forbidden. They were moved through the prison hooded in masks, exercised in separation in specially designed yards, and were placed in separate stalls, referred to as coffins by the prisoners, at chapel (Figure 2.1). Prisoners were trained in a trade and taught by schoolmasters, preparing them for their new lives in the colonies. The moral and spiritual reformation of the convicts fell mainly to the chaplains who also directed the work of the schoolmasters and selected books for the library. Prisoners attended daily religious services and the prison chaplains devoted many hours each day to visiting convicts in their cells, discussing their past lives and exhorting them to repent and reform. Chaplains gained detailed knowledge of each convict, his character, disposition and habits, which was minutely recorded in journals and general registers. The chaplains also assumed a central role in directing the separate system.Footnote 90 At Pentonville Reverend James Ralph and his successor, Reverend Joseph Kingsmill were second only to the governor in terms of authority.

Figure 2.1 The chapel, on the ‘separate system’, in Pentonville Prison during divine service

During the 1840s, Pentonville’s formative years, the chaplains affirmed their expertise and close knowledge of the minds of convicts, gained through their cellular visitations and observations, which afforded them the ‘best opportunity of knowing their [convicts’] feelings’.Footnote 91 The prison’s regulations underlined the importance of vigilant observation by the chaplain, with the assistance of the surgeon, of the ‘state of mind of every prisoner’.Footnote 92 Reverend Kingsmill’s report for 1845 provided a detailed assessment of convicts’ responses to the separate system, commenting on the determination of some, unable to withstand the degradation and isolation, to break prison rules and secure removal from the prison. The ‘well educated and intelligent men’, those who were ‘always thinking’, he claimed, benefited from the regime. While these convicts reportedly found separation a ‘severe punishment’, they were ‘grateful’ for ‘the religious and moral advantages which a paternal Government afforded to them’.Footnote 93 Kingsmill, who linked mental wellbeing to prisoners’ capacity to be reformed and their minds reanimated through education, would later moderate his support for separation.

While Crawford, Russell and Kingsmill publicly defended Pentonville and the separate system, with Crawford and Russell insisting that the availability of the officers and regular visitations from prison personnel distinguished it from the system at Eastern State Penitentiary and protected the convicts’ minds, inside the prison there were regular consultations and exchanges between chaplains, medical officers, schoolmasters, warders and Pentonville’s Commissioners regarding the prisoners’ mental and physical health.Footnote 94 The risk to the mind of convicts and the danger of mental breakdown was acknowledged in the Pentonville Prison Act (1842), which specified that convicts who showed signs of mental illness were to be reported to the Secretary of State and transferred to an asylum.Footnote 95 In practice, as will be demonstrated below, this happened infrequently and usually only after extensive deliberation. Evidence of growing concern about prisoners’ mental wellbeing, however, occurred in 1843, when Chaplain Ralph was forced to resign following a spike in cases of ‘morbid religious symptoms’. Convicts were reported to be suffering from insanity, mania, depression and hallucinations, many with religious overtones, which Rees and the Pentonville Commissioners linked to Ralph’s excessive religious teachings.Footnote 96 In December 1843, for example, Rees reported ‘That Prisoner Wm. Cowle Reg. No. 385 is decidedly hallucinated, said, that Christ pervades him, & gives him sensations’ and ‘That the Devil visits him & converses with him in a flame of fire’. Cowle was removed to the infirmary but his condition steadily deteriorated; he became violent, talked only about religion and refused food. In January 1844 Rees recommended he be removed to an asylum.Footnote 97 Faced with several disturbing cases, Rees suggested ‘Prisoners, R. Henshaw Reg. No. 210 and Wm. Johnson Reg. No. 222 should not go to the chapel service for a few days’ and that bibles, prayer books and hymn books be removed from some prisoners’ cells.Footnote 98

By the end of 1843, Ralph had been replaced by the Assistant Chaplain, Kingsmill, but Medical Officer Rees and Chaplain Kingsmill continued to report on convicts who were ‘strongly affected by religious impressions’, threatened to self-harm or commit suicide and were ‘suffering much from mental depression’.Footnote 99 Kingsmill and Rees disagreed on individual cases, such as that of convict James Graham [convict no. 635], who described his delusions relating to death and his mother’s health to Kingsmill in July 1845. Kingsmill concluded there was ‘nothing in Reg. 635 … indicating the presence of any delusions’. However, Rees, who also called upon the advice of physician Commissioners Brodie and Ferguson, resolved he was insane and should be removed to an asylum. This decision was subsequently amended when Dr Seymour visited the prison to advise and concluded that Graham would recover. Graham continued to experience attacks of mania and was eventually removed to Bethlem in November 1845.Footnote 100

Many of these protracted and time-consuming exchanges were concerned with identifying whether convicts’ behaviour denoted ‘real’ cases of insanity, requiring removal to Bethlem, or were cases of malingering, weak-mindedness, or evidence of convicts’ inability to withstand the severity of the regime. In dealing with them, the Pentonville officers and Commissioners were keen to protect the reputation of the prison and the separate system against accusations of cruelty, inhumanity, and provocation of mental breakdown. Transfers to lunatic asylums, as in the case of Graham, were resisted and delayed, in order to ‘test’ or verify diagnosis of insanity and to downplay the incidence of mental disorder among convicts. Pentonville’s official publications limited their reporting of mental illness largely to those convicts transferred to asylums and cases of suicide.Footnote 101 The chaplains’ and medical officers’ detailed investigations into convicts presenting with hallucinations, anxiety, self-harm, mania, depression, morbid feelings and irritability, recorded in minute books and the chaplain’s journal, were not replicated in annual reports. Rather, these public documents insisted that the minds of the prisoners were improved through seclusion, teaching, and preaching and that the mental condition of the prisoners was ‘most satisfactory’.Footnote 102

The dangers of the system were, however, becoming increasingly evident. Already in the 1840s, the Home Office recommended pardons and medical discharges for Pentonville convicts deemed unfit for transportation or whose life would be endangered by further imprisonment.Footnote 103 Of those pardoned on medical grounds, the majority suffered from physical illnesses such as convict G.M. (no. 9640), who was discharged in December 1846 with pulmonary consumption.Footnote 104 Medical pardons were included in Pentonville’s mortality statistics suggesting convicts were released in anticipation of their deaths.Footnote 105 There were few medical discharges of prisoners with symptoms of mental distress or insanity, although in June 1849 convict Clewett (no. 1860) was ‘discharged with a free pardon, on medical grounds, suffering under chronic disease of the brain’.Footnote 106

The factors informing a decision to organise medical releases were not recorded in great detail, and it is unclear how such decisions were reached and whether the advice of prison medical officers concerning the health of the prisoner was a decisive consideration. The potential danger to the public posed by prisoners experiencing mental distress, however, may explain prison officials’ reluctance to authorise medical releases on these grounds. For example, Sir George Grey rejected a request from Pentonville’s Commissioners to pardon convict Beckett, who had served only fifteen months of his sentence for a ‘serious’ offence. Beckett was reported to be labouring under hallucinations.Footnote 107 In November 1848, he had attracted the attention of Pentonville’s Governor and Medical Officer Rees when he was noted to be ‘strange in manner’ – he ‘fancies he hears his name called, and sees it written upon the walls’ – and was recommended for transfer to the garden class.Footnote 108 On 23 December 1848, Rees noted that Beckett was still hallucinating and removed him to the prison infirmary where he remained until 31 December before he was returned to normal prison discipline.Footnote 109 Within four days Beckett was back in Pentonville’s infirmary where he continued to experience delusions, hearing noises and voices speaking to him.Footnote 110 His condition deteriorated further, prompting the Pentonville Commissioners to submit their unsuccessful request for his medical release in March 1849.Footnote 111 While it is uncertain whether Becket was eventually discharged, his case highlights the selective use of medical releases in cases when convicts exhibited signs of mental distress or insanity, and the cautious approach of the Home Office when dealing with such cases.

Further emphasising the risks of separation, between 1845 and 1848, a series of damming reports highlighted the poor mental condition of convicts removed from Pentonville and transferred onto ships destined for transportation to Van Dieman’s Land. On boarding ship, the ‘Pentonville graduates’ exhibited alarming symptoms, variously described as epileptic, convulsive fits and hysteria. Surgeon-superintendent to the Stratheden, Henry Baker, described how within forty-eight hours of arrival on the ship, nineteen Pentonville convicts were affected with ‘Epileptic Fits’, many suffering three or four. Convicts sent from other prisons were free from such attacks, which Baker related to the eighteen to twenty months Pentonville prisoners had spent in separate confinement.Footnote 112 To diminish the outbreaks of ‘mental imbecility’ on board ship and prepare convicts for the ‘ordinary habits of life’, convicts destined for a transport colony were placed in association at Millbank prison for short periods prior to embarkation or in associated work in Pentonville, carrying out tasks such as wood cutting or garden work. These attempts to prevent the transition from the separate system to association being ‘too sudden and overwhelming’ largely failed.Footnote 113

Though removals to Bethlem were resisted, the number of convicts transferred there began to build up, confirming fears about the negative impact of the regime on prisoners’ mental wellbeing, and prompting public commentary. Elizabeth Fry was concerned that the separate system would cause a decline in bodily and mental health, and a number of widely read periodicals pitched into the debate, with the Illustrated London News denouncing the Pentonville regime as destructive of human individuality.Footnote 114 In 1847 Peter Laurie, President of Bethlem Hospital, condemned Pentonville’s system of discipline in The Times, commenting on the steady flow of ‘lunatic’ prisoners from Pentonville to Bethlem that he attributed to the damaging effects of the separate system on the minds of prisoners.Footnote 115 Laurie had been an opponent of the separate system since its introduction at Millbank and in 1846 he published a comprehensive critique of its impact on prisoners in Britain and America, providing figures on rates of mental breakdown in individual prisons to uphold his argument.Footnote 116

After the sudden deaths of Crawford and Russell in 1847, the regime at Pentonville was toned down, and Jebb and other Pentonville Commissioners reasserted their influence over the management of the prison. In 1848, the length of separation was reduced to twelve months and to nine months by 1853. Also in that year, Portland Prison was opened to allow for associated labour among convicts in public works prisons prior to transportation.Footnote 117 The link between Pentonville and transportation diminished further in 1853 with the replacement of sentences of less than fourteen years’ transportation with penal servitude.Footnote 118 By the late 1840s, even Chaplain Kingsmill, formerly a staunch advocate of the separate system, was expressing ambivalence about the regime. Initially confining his concerns to his journal, his daily observations of cases of mental breakdown and the undermining of the physical and mental energy of the prisoners prompted a more public expression of doubt in his annual reports. In 1849 he declared in his report to the Pentonville Commissioners, that ‘Its value in a moral point of view has been greatly over-rated’, though he believed the separate system still offered the opportunity for reflection, to awaken the conscience of prisoners and was the best deterrent against the repetition of crime.Footnote 119 Reflecting on his own experiences in 1852, Kingsmill repeated the observations of a physician employed at a New Jersey Penitentiary:

A little more intercourse with each other, a little more air in the yard, has the effect upon the mind and the body that warmth has on the thermometer; almost every degree of indulgence showing a corresponding rise in the health of the individual. That an opinion to the contrary should be advocated at this time seems like a determination to disregard science in support of a mistaken but favourite policy.Footnote 120

The Dogma of Separation

Despite increasing evidence that the Pentonville regime could inflict harm on the minds of prisoners, both central and local-level prison administrators retained a strong commitment to the separate system. In his report on Belfast House of Correction for 1849, Inspector Frederick Long acknowledged there were ‘evils’ as well as benefits to the separate system of confinement. In terms of the ‘injury caused to the health of the prisoners’ and the effect ‘frequently produced in causing aberration of mind’, drawing on the opinions of Dr Purdon, surgeon for the House of Correction, he noted that ‘in no one instance has the mind of any individual become affected in the prison’.Footnote 121 Purdon claimed young prisoners seldom suffered and that there was ‘not a single record of a female suffering in any respect from the system’.Footnote 122 Long also noted it had never been ‘necessary to relax the discipline on medical grounds’ and that some prisoners had endured separation for two years without any adverse consequences. He concluded there was ‘nothing in the discipline of the prison that is the least injurious to the mental or bodily health of its inmates’.Footnote 123

Although Kingsmill’s support became more muted, driven by his experiences at Pentonville, most chaplains were enthusiastic. They published influential texts on the system and its benefit to the mind, and in so doing shored up their own influence. In 1846, Reverend John Field, chaplain at Reading Gaol, dismissed concerns about the injurious effect of separation on prisoners’ physical health, claiming mortality rates at Eastern State Penitentiary and at Reading had improved following its introduction.Footnote 124 Field drew on a series of reports by the Inspectors of State Prisons in America, Pentonville’s Commissioners, and several official inquiries into prison discipline in England, which downplayed claims that separation prompted insanity among prisoners. Rather than blaming the separate system, cases of insanity were, he insisted, a product of hereditary predisposition and largely attributable to the admission of prisoners with existing mental disorders that re-emerged while in confinement.Footnote 125 His book was published in the same year as Laurie’s denouncement of the separate system, and Laurie mocked Field’s eulogising of his own exertions in his annual report on Reading Gaol, as well as his efforts to glean information respecting the sanity of the ‘scattered relations’ of some twenty-seven prisoners: ‘proof that these twenty-seven were breaking down – that their minds were giving way; and then this evidence was hunted up to prop a falling case’.Footnote 126

The ‘exemplar of the reformist chaplains’ was Clay of Preston.Footnote 127 Under his influence, the county’s newly appointed visiting justices introduced separation at Preston and Kirkdale prisons after 1846.Footnote 128 Reverend Richard Appleton, Field’s predecessor at Reading and an ardent supporter of separation, was appointed chaplain at Kirkdale Prison. In his 1848 annual report, he insisted that ‘I do not see any tendency in it [separation] to overthrow, or even enfeeble, the mind’.Footnote 129 In his 1852 defence of the system, Reverend John Burt asserted that it was the modifications introduced to the system after the deaths of Russell and Crawford, relaxing the ‘rigour’ of separation, that had rendered it ‘inoperative or unsafe’. In its most extreme manifestation, Burt claimed, there had been few cases of mental breakdown, and these were attributable to existing mental weakness in the convicts effected.Footnote 130 Burt not only persisted in his support of separate confinement, he sought exposure of the prisoners to the purest, ‘Pentonville’, form.

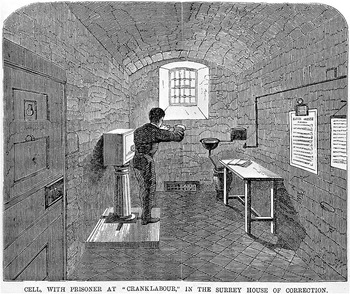

Despite this enthusiasm, some experiments with the regime, including versions implemented at Birmingham Borough Gaol and at Leicester Gaol, were excessively cruel, and there were allegations of abuse of power by prison officials, severe punishments and deaths among prisoners. Birmingham had opened in 1849, and was designed for the separate system, with Captain Alexander Maconochie as the first Governor. Although Maconochie was soon replaced by Lieutenant William Austin, a modified version of Maconochie’s ‘mark system’ was implemented for prisoners aged under seventeen. In the early 1850s, a wave of suicides and suicide attempts among juvenile prisoners, rumours of ‘alleged cruelties’ to prisoners, including the weak-minded, and an

Figure 2.2 Cell with prisoner at ‘crank labour’ in the Surrey House of Correction

inquest into the suicide of a fifteen-year-old prisoner, Edward Andrews, prompted an inquiry into the management of the gaol.Footnote 131 The subsequent 1853 Royal Commission found that prisoners had been cruelly and inhumanly treated and revealed instances of excessive and punitive infliction of ‘crank work’, repeated and prolonged flogging, and dangerous restriction of prisoners’ diets leading to severe physical deterioration and repeated suicide attempts among prisoners.Footnote 132 One juvenile, Richard Scott, whom the chaplain described as being ‘nearly an imbecile’, had made three separate attempts at self-destruction.Footnote 133 Emphasising the illegality of the actions of prison staff, especially the surgeon, Mr Blount, and Austin, and clearly anxious to disassociate the separate system from such actions, the Commissioners noted Blount had omitted to provide proper care

in the treatment of some classes of prisoners for whose safety special arrangements were needed: the epileptic, those of unsound mind, and those who had manifested a disposition to commit or attempt suicide. To leave men thus afflicted in separate cells, without any attendant, was at the least a grave error of judgement.Footnote 134

The events at Birmingham Gaol gained extensive local and national press coverage, and were the basis of the Charles Reade’s novel, Its Never too Late to Mend, published in 1856. However, the scandal, and a similar outrage at Leicester Gaol, which also resulted in an official inquiry into allegations that prisoners were excessively punished for failing to complete task work at the crank, did not undermine support for the separate system or the authority of prison officers.Footnote 135

Meanwhile, in 1850, the long-awaited model convict prison, designed for 450 single occupancy cells for male convicts, opened at Mountjoy in Dublin. The responsibility for overseeing the implementation of separate confinement in the prison fell to Henry Martin Hitchins, the Inspector General of Government Prisons in Ireland.Footnote 136 He had visited Pentonville Prison in January 1850, three years after the deaths of Crawford and Russell, to observe the prison ‘at all hours, and in all stages of its discipline’. In his subsequent report, he commented on the modifications being introduced at Pentonville, in particular the almost universal rejection of the prolonged period of probation ‘as too severe, affecting both the mental and physical condition of the convict and tending to stupefy’. Hitchins was especially critical of the promotion of religious instruction at the prison, dismissing it as a ‘dead failure’. The chapel seats at Pentonville, he noted, ‘disfigured by grotesque carving and gross inscription, attest the diligence if not the piety of the inmates’.Footnote 137

At Mountjoy, the role of the chaplains – Roman Catholic, Church of Ireland and Presbyterian – was to be less influential than in England. They were ‘to visit convicts in cells for conversation every day and visit school classes’ but were forbidden from exercising ‘direct control over the School master’, who, in turn, was to confine his work to secular education. Concerns over allegations of proselytism, especially in relation to educational and religious instructions, persisted in prisons, and in other nineteenth-century institutions, including workhouses and asylums. To guard against these allegations, and protect the minds of prisoners, Hitchins selected chaplains who were of a ‘high character’ and less ardent in their ministry.Footnote 138 He also insisted that the ‘disturbance’ of chaplains’ visitations to cells should not interfere with convict labour, especially at convict depots such as Smithfield.Footnote 139 For Hitchins, separation was to be the ‘principle’ upon which Mountjoy prison would be conducted, but ‘many details of Pentonville which being extreme are necessarily futile, may be safely avoided’.Footnote 140 The strengths of the regime were its capacity to act as a deterrent – the ‘dread’ of the convict returning to the separate cell – and as a mechanism for enforcing education and industrious habits, either through convict labour or reading. Its success depended on the ‘minds of the prisoners being fully occupied’.Footnote 141 ‘The great object … to be attained’, Hitchins asserted, was ‘to deter from further infraction of the law.’Footnote 142

Aware of the links being made between the separate system and insanity, Hitchins warned Mountjoy’s first Medical Officer, Dr Francis Rynd, who had previously worked at Smithfield Convict Depot, to carefully assess the mental as well as the physical condition of incoming convicts.Footnote 143 As he noted, the criticisms of the regime were ‘principally directed to the injurious tendency of [a] long period of separate confinement to produce a general debility of mind and body’. Echoing the concerns of Pentonville’s Chaplain Kingsmill on the endangerment of the mind resulting from separate confinement, Hitchins outlined three groups of prisoners most at risk of succumbing to ‘utter prostration of the mental powers’ or ‘imbecility’.Footnote 144 These were prisoners whose ‘prevailing character … is that of sullenness’ or in whom ‘insanity is hereditary’; those unable to acquire a trade, or benefit from instruction or education; and prisoners who demonstrated a ‘tendency … to dwell unhealthily on any one subject, to the exclusion of all others’.Footnote 145 Rynd had previously expressed doubts about the effectiveness of the separate system, observing in 1846 that

Men who from low moral principles, confinement, fear of punishment, grief at their separation from family and friends, and perhaps from remorse from crimes have lost vigour and elasticity of life so protective of sound health, and sunk into the torpid depression of mind and body that renders them so susceptible of disease and above all of fever.Footnote 146

In selecting convicts suitable for the regime at Mountjoy, Rynd and Hitchins also adapted the ‘Pentonville’ criteria. Initially, it was proposed to transfer prisoners directly from county gaols to Mountjoy ‘so that separation might be in Ireland, as in England, the first stage in convict discipline’. However, the poor physical condition of convicts, many still suffering the effects of the Great Famine, rendered large numbers unsuitable for the severe regime at Mountjoy.Footnote 147 Rather than admit convicts ‘notoriously unsuited to the discipline’, Hitchins and Rynd concluded the ‘sturdy criminal’ was more suited to the regime:

The expectations which may be formed of a beneficial change from youth, previous character, or inexperience in vice, are thus practically set aside, while the sturdy criminal is pronounced as a suitable subject for its moral and industrial advantages, and the indulgence of tickets-of-leave, because he alone is physically fit to undergo the restrictions of the system.Footnote 148

The Governor at Mountjoy, Robert Netterville, implemented Hitchins’ modified system. However, following an inspection in July 1850, Hitchins criticised Netterville for permitting the rule of silence to break down while prisoners were at work. He also maintained that the prison officers were too lenient and reminded the governor that

prisoners committed to your charge have been convicted of grave offences against God and man, that they have forfeited their civil rights and are confined as much, to say the least, to protect society against their evil practices as to afford them an opportunity of repentance and reformation. It is therefore of primary importance that the prisoners should be brought to a proper sense of their condition and after the religious exhortations of the chaplains nothing so directly tends to effect this object as a firm and steady exercise of a severe discipline.Footnote 149

Rynd continued to reject large numbers of prisoners; in June 1854, the Prison Commissioners reported that he had excluded 35 per cent of the prisoners sent to him as ‘unfit to undergo separate imprisonment of 12 months’ duration, or incapacitated for employment at the trades’.Footnote 150

While the authority of the chaplains and their significance within the separate system had diminished following Pentonville’s experiences, they remained significant actors in implementing separation at Mountjoy and were ‘implicitly confided in by the convicts, the depositary of his secret thoughts and wishes’.Footnote 151 Some, such as the Protestant Chaplain, Reverend Gibson Black, were strong advocates of the regime. Assessing the progress of the prison after its first full year in operation, Black observed in 1851:

Under the system of complete isolation, strictly adhered to for so long as the convicts’ health can endure it, I would not despair of the most hardened offender being raised from degradation, and made susceptible to the sanctifying influences of the Gospel of Christ. The Word of Truth addressed to the most guilty in the solitude of the cell, where all disturbing circumstances of an external character are shut out, is often reflected on with an intensity of interest which exemplifies the meaning of that pointed inquiry – ‘Is not my word like as a fire! saith the Lord; and like a hammer that breaketh the rock in pieces?’Footnote 152

Despite Hitchins’ instructions aimed at restricting the chaplains’ interference with the educational system at the prison, Neal McCabe, the Roman Catholic chaplain, provided a detailed assessment of the quality of school instruction, and, according to his account, he was deeply involved in the prison school. In contrast, Gibson confined his comments to religious instruction at the prison. McCabe’s report for 1851 also included a detailed exposition on the relationship between crime rates, criminality and poverty in which he demonstrated some ambivalence about separate confinement, characterising it as a regime that encouraged dishonesty and dissimulation:

I could not venture to offer any opinion on the merits of the silent and separate system, as compared with other systems of prison discipline.… I would prefer association to a system under which they are incessantly endeavouring to communicate with each other, and with success, whilst pretending the strictest regularity. Now, such a system of dissimulation is most injurious to their moral training; for sincerity and openness of character are virtues which convicts, in general, require to learn.Footnote 153

Hitchins and Rynd were confident of the modifications implemented at Mountjoy and reported with satisfaction on the absence of mental disease in the prison during 1851. They attributed this to the careful selection of convicts, the close vigilance and attention paid to prisoners by the officers, and the provision of trade and employment to occupy the minds of prisoners.Footnote 154 In his own report for the year, Rynd went further, stressing that the success was due to the ‘almost unrestricted power’ conceded to him as medical superintendent of the prison, which permitted him to introduce ‘relaxations of strict prison discipline’ essential for the management of the convicts.Footnote 155 He did not refer in his report to the attempted suicide of convict Brennan, who cut his throat with a knife in his cell in January 1851. In his initial assessment of Brennan, Rynd had been unprepared to state whether the suicide attempt was caused by mental debility or was a feigned attempt. The prisoner had previously self-harmed while confined at County of Down Gaol, wounding himself several times with sharpened pieces of tin and glass and evading restraints. The medical officer at the Down Gaol, Dr Brabazon, also alleged that Brennan did not intend to seriously injure himself and had previously simulated dysentery by adding blood to his stool. After his suicide attempt at Mountjoy, Rynd ordered Brennan to be placed in secure restraint.Footnote 156

Convicts diverted from Mountjoy as unsuitable for the regime were transferred to Spike Island Public Works Prison and to Philipstown Government Prison. Spike had operated for several years ‘as the place of last resource to the invalid convict, or an asylum to the incurable’. In the annual report for 1851 it was reported that 20 per cent of prisoners at Spike were chronic patients of ‘one kind or another’ and that 600 prisoners were either in hospital or convalescent wards, at a time when there was accommodation for 2,300 prisoners.Footnote 157 Mountjoy convicts, who had undergone the full rigour of separation, were then removed to Spike but maintained in ‘distinct wards and separate working parties’ away from other prisoners to avoid contamination while awaiting transportation.Footnote 158 A group of seventy-five convicts sent by steam ship from Mountjoy to Spike in May 1851 had been in separation for periods varying from ten to fourteen months.Footnote 159 While Mountjoy was claimed to be relatively free of ‘mental disease’, incidences of mental distress and disorder were reported at the other convict depots and prisons where Mountjoy convicts were transferred. Alongside numerous ‘weak-minded’ convicts removed from Mountjoy to Spike Island, other Spike prisoners, such as Michael Hayes and Thomas Kehoe, were diagnosed as insane. Kehoe, a convict under sentence of ten years’ transportation, was transferred from Spike to Dundrum Lunatic Asylum in March 1851.Footnote 160

Women held at Grangegorman Convict Depot also showed signs of insanity. Mary Kelly, committed to Grangegorman in August 1845, had allegedly feigned insanity on hearing she was to be transported. When finally placed on board the convict ship, The Tasmania, with 136 other women and thirty-seven children, she ‘exhibited symptoms of violent insanity, or assumed them’, scaring other prisoners, by tearing their ‘clothes, caps and hair … striking the commander, surgeon, and sailors’.Footnote 161 Reverend Bernard Kirby, chaplain to the Grangegorman Depot, failed to calm her and she was eventually removed back to Grangegorman, and in March 1846 transferred to Richmond Lunatic Asylum.Footnote 162 By 1849, Grangegorman had forty cells for prisoners in separate confinement, and held sixty-six female lunatics in different wings of the prison.Footnote 163 Again, in July 1850 two women were declared unfit for embarkation on a transport ship on grounds of insanity and recommended by the medical attendant for removal to an asylum or for commutation of their sentences.Footnote 164 Such was the concern about conditions at Grangegorman, in October there were calls to abandon it as a convict depot and instead establish a distinct institution that fully implemented the separate system or for female convicts to be sent directly to the colonies.Footnote 165 Meanwhile, Dr Francis White, in his role as the Inspector of Lunacy, encountered insane convicts from Spike Island when visiting Dundrum Criminal Lunatic Asylum. Noting that these convicts were allowed ‘free intercourse’ while at Spike, he asserted that his experience of Mountjoy and other prisons did not support claims that separate confinement generated insanity.Footnote 166

Over the next few years, the incidence of feigned and ‘true’ suicide attempts at Mountjoy increased and Rynd continued to reject large numbers of prisoners as unfit for the regime. Correspondence between Hitchins and Governor Netterville suggests that in 1854, a batch of 13 prisoners were removed from Mountjoy on Rynd’s orders in February and a further 12 in April, 88 in June and 126 in October.Footnote 167 In the same year, two suicide attempts and a third incident described as a feigned suicide attempt were reported to Hitchins.Footnote 168 The length of time prisoners spent in separation had also been extended beyond Hitchins’ original recommendations. In April 1854, Rynd submitted his third application requesting the removal of convicts who been in separation in Mountjoy from twelve to sixteen months, informing Hitchins that one had died and a further eleven were in hospital.Footnote 169 In 1855, Rynd commented on the prison hospital being full of these ‘patients broken down by … confinement’.Footnote 170 Observing the impact on convicts of being kept for prolonged periods in separation – ‘from nine months to eighteen, frequently, from various causes, prolonged to twenty, and even to twenty-two months’ – Rynd noted that every convict:

not only experienced all the depressing influence of confinement (generally twenty-two consecutive hours in the cell at a time), but was exposed to the effects of trade labour in the cell, which, every where, and under every circumstance, has been found so injurious. All convicts could scarcely be supposed to possess mental and physical strength sufficient to sustain them under trials so protracted and severe.Footnote 171

In that year there were four suicide attempts and one case of ‘feigned’ insanity at Mountjoy, yet in his official report Rynd noted there were no cases of mental disease.Footnote 172