Introduction

Surgeons have long told stories about themselves and their history. As Christopher Lawrence has suggested, and as we shall see in this book, these stories often reveal more about the image that their tellers sought to project of themselves and their contemporaries than they do about the various mythical, half-remembered, and stereotyped pasts they invoked.Footnote 1 This tradition of storytelling, of historicising surgery in order to understand the present, had its roots in the writings of medieval surgeons such as Guy de Chauliac (c.1300–68), but, like historicism itself, it really came to prominence at the end of the eighteenth century and beginning of the nineteenth.Footnote 2 It was in this period, or so contemporary surgeons claimed, that surgery had become a fully fledged scientific discipline that had finally distinguished itself from its traditional associations with manual craft. This story had its institutional correlate in the split of the surgeons from the Barbers’ Company (1722 in Scotland, 1745 in England) followed by the creation of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in 1778 and the Royal College of Surgeons of London (later England) in 1800. Indeed, it was within these new institutional structures that surgery’s mythical rebirth was most frequently, and most visibly, commemorated and rehearsed.

The first part of Emotions and Surgery is concerned, in large part, with exploring the professional cultures, identities, and ideologies of a generation of British surgeons that came of age in the very late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries: a generation of Romantic surgeons. Perhaps the most prominent claim that this generation made for the transformation of their art in the fifty or so years prior to 1800 was its increasing scientific sophistication: the re-founding of surgical practice on the basis of sound anatomical knowledge, rather than mere empiricism. If the humanist surgeons of the sixteenth century had struggled to wrest learned surgery from the intellectual domain of the physician, then surgeons of the later eighteenth century had, it was claimed, made anatomical and physiological learning their own.Footnote 3 In fact, they had, to a significant degree, made medical knowledge their own. The eighteenth century produced a number of surgeons whom posterity would venerate as exemplars of this new-found theoretical and operative self-confidence. These included men such as William Cheselden (1688–1752) and Percivall Pott (1714–88).Footnote 4 However, by far the most iconic figure, and the man who, as Lawrence observes, would be ‘shaped into the “father of scientific surgery”’, was John Hunter.Footnote 5 It was Hunter whose name would, in 1813, be immortalised in the form of an annual oration at the Royal College of Surgeons of London, and it was his likeness, in the shape of Henry Weekes’ (1807–77) statue of 1864, that would take pride of place in the College’s Museum.Footnote 6 As Lawrence suggests, while English surgeons made Hunter their own, those in Scotland told a different story (somewhat ironically, given that Hunter was a Scot).Footnote 7 For Edinburgh chroniclers writing in the mid-nineteenth century, it was John Bell who was celebrated as ‘the best surgeon that Scotland had then produced’Footnote 8 and ‘the reformer of Surgery in Edinburgh, or rather the father of it’.Footnote 9 Indeed, the prowess of Scottish surgeons in the early to mid-nineteenth century, including the brothers John and Charles Bell, as well as Robert Liston and James Syme, allowed their contemporaries to imagine that Scottish surgery had initiated a revolution all of its own. Writing to his uncle from Edinburgh on New Year’s Day 1833, the young Cumbrian surgical pupil Andrew Whelpdale spoke of ‘the beauty of the modern School of Medicine in Edinbro [sic]’. ‘I can assure you’, he wrote, ‘that there is as much difference between a surgeon of the Old School and one of the New as you can possibly imagine. We have here one of the best operators in the world Liston – A pupil of his is almost the equal, and indeed is far superior in some things to a practised surgeon of the old school’.Footnote 10

In praising the ‘new school’ of Edinburgh surgery, founded by John Bell and raised to greatness by Liston, Whelpdale mocked the pretensions of the physician and asserted the claims of surgery to be the superior science. ‘To shew you the contempt in which the Doctors are held by the great men here’, he wrote, ‘I will relate a story about Liston’. This story, which involved Liston asking his students whether they thought ‘there existed any one more ignorant than a Doctor?’, was doubtless apocryphal. But Whelpdale also confided that his personal tutor in anatomy, the celebrated (and infamous) Robert Knox (1791–1862), had told him that he ‘is sorry he graduated himself [i.e. became a physician] & would not let a son of his graduate’. ‘Besides’, Whelpdale concluded, ‘no one gets on now but general practitioners. The surgeons seldom call in a Physician’.Footnote 11

Whelpdale’s letters nicely capture the sentiment, prevalent in the early nineteenth century, that the traditional balance of power between surgery and medicine was beginning to shift. Indeed, it is notable that he referred to this new ‘School of Medicine’ in purely surgical terms. This accords with an established historical narrative. Numerous historians have argued that it was during the nineteenth century that surgery came to prominence as a profession, eventually displacing medicine in the hierarchy of social and intellectual prestige. Indeed, within the historiography of medicine, surgeons are, like the middle classes of old, perpetually rising.Footnote 12 And yet, aside from a few examples, there is surprisingly little scholarship on what this process actually looked like or how it shaped British surgical culture.Footnote 13 This is certainly true when compared to the well-established historiography on the rise of surgery in France, which traces its influences through the eighteenth century to the clinical revolution of early nineteenth-century Paris.Footnote 14 Emotions and Surgery is not intended to function as a political history of surgical professionalisation in Britain, at least not as conventionally conceived. What it does seek to do is to provide a cultural historical account of nineteenth-century British surgery through a fine-grained analysis of surgical performance and identity at a time of remarkable transformation.

Emotions, this book contends, are critical for understanding nineteenth-century surgical culture, and they played an especially vital role in shaping Romantic surgical practice, experience, and identity. In his Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery (1821), Charles Bell claimed that ‘it depends on the conduct of those who are now entering their Profession, whether Surgery will continue to be confounded with meaner arts, or rise to be the very first in estimation’. As we shall see in Chapters 2 and 3, he, like many of his contemporaries, framed the ‘knowledge’, ‘honour’, and ‘abilities’ of surgeons largely in terms of their capacity to act with, as well as to manage and manipulate, feeling.Footnote 15 This first chapter argues that one of the key features of the epistemic transformation that characterised the inheritance of Romantic surgery, namely a greater knowledge of human anatomy, was an increasing emphasis upon operative restraint and a caution against radical, dangerous, or so-called heroic procedures deemed likely to produce excessive suffering or even death to the patient. It is important to see this transformation not simply as an objective, epistemological phenomenon, but also as a subjective, ideological one. The deprecation of unnecessary or rash surgical intervention was the product not only of greater anatomical knowledge, but also of social and cultural change, the corollary of an emotional regime founded upon the values of sensibility, sentiment, and sympathy. As we shall see in successive chapters, these values had a profound impact on surgical identity and practice, as well as on patient experience. In this chapter, however, our focus is on their implications for the literal performance of surgery, for the manual skills and bodily dispositions deemed necessary for the cutting of one’s fellow creatures: the ‘hexis’ and ‘habitus’, as it were, of Romantic surgery.Footnote 16 Thomas Schlich is one of the few historians of surgery to consider the place of manual skill and styles of operative performance in the shaping of surgical culture and identity.Footnote 17 Like other commentators, such as Peter Stanley, he characterises the early nineteenth century as an era defined largely by speed, something that was not only deemed necessary for the mitigation of pain, but also became central to the ‘mystique of the heroic surgeon’.Footnote 18 Both Stanley and Schlich point to the existence of other operative ideals, notably grace, composure, and caution.Footnote 19 Moreover, Schlich rightly suggests that operative styles ‘needed to be controlled by a moral framework to make sure that the surgeon’s performance stayed within the limits of his patients’ best interests’.Footnote 20 This chapter corroborates that suggestion but endeavours to go further, underscoring the moral complexity of Romantic surgical performance by suggesting that speed was far from being the principal attribute for which surgeons of the period were admired. Indeed, it argues that a new-found emphasis upon restraint actually had deeply ambiguous implications for the place of manual dexterity and operative flair in contemporary surgical culture and identity. On the one hand, physical dexterity and operative ‘boldness’ were praised as both practical necessities and signifiers of manual and mental aptitude, but, on the other, surgical commentators of the period increasingly expressed distrust of excessive flamboyance and self-regard, which they came to see as the expression of an inauthentic surgical persona.

With the expansion of hospital-based teaching in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, operations were performed with increasing frequency in front of sometimes large audiences of students and fellow practitioners. Schlich and others have suggested that such public performances encouraged surgical ‘showmanship’.Footnote 21 As we shall see, especially in Chapter 4, surgeons were indeed scrutinised and judged for their operative performance, sometimes quite harshly. However, surgical performance in the Romantic operating theatre involved more than the mere display and evaluation of style and skill. The operating theatre was, in fact, a complex political and emotional space that required careful moral management.

If the performative dimensions of Romantic surgery were complex and ambivalent, then those qualities can be said to have crystallised in the form of one of the Romantic era’s most celebrated operators, Robert Liston. Liston’s renown as perhaps the greatest operative surgeon of the 1830s and 1840s was spread by contemporaries such as Andrew Whelpdale and has been sustained by subsequent generations of historians. And yet, while Liston is famed as a bold and skilful operator, and as the first surgeon to perform an operation under anaesthesia in Britain, he is often represented, especially in more sensationalist accounts of the history of surgery, as the last of the surgical old guard, a speed-obsessed showman whose rashness hints at the cruelty and brutality of the pre-anaesthetic era.Footnote 22 In her account of John Elliotson’s (1791–1868) mesmeric demonstrations in the operating theatre at University College Hospital, Alison Winter remarks that ‘insufficient historical study has been undertaken to recover the kinds of surgical displays that made Liston so immensely effective as a surgical performer’.Footnote 23 As we shall see in the final section of this chapter, the solution to that riddle is not necessarily straightforward. For one thing, Liston’s performances, and their reception, were shaped by the twin demands of care and cure, demands that were not always easily reconcilable. Moreover, his reputation as an operator was not simply an objective corollary of his abilities, but was formed by a variety of complex social and political factors, not the least of which were the factious cultures of medical reform and the occasionally antagonistic relations of Anglo-Scottish surgery.

Anatomy, Science, and the Decline of Heroic Surgery

In order to understand how the notion of operative restraint became central to Romantic surgical identity, it is first necessary to consider how it came to be tied to a customary narrative of social, intellectual, and epistemological self-improvement. Surgeons of the period were profoundly conscious of their historically questionable status and of their associations with empirical, rather than scientific, practice. However, in their writings and lectures, they crafted a narrative of surgery as risen to respectability from humble origins in less than a hundred years. Speaking to his St George’s Hospital class in 1820, Benjamin Brodie (1783–1862) claimed:

In this and in many other Countries where surgery was first pursued as a separate profession, it was held in low estimation. Even in the beginning of the last century, the Surgeon was a subordinate person, who Trepanned and performed amputations, under the direction of the Physician. But since that time, our profession has made rapid strides towards its present dignified and honourable station. It has been adorned in this Country by Cheselden, Hunter, and Pott, and we may safely say, that at the present day, the Surgeon in the Metropolis, ranks in public estimation, at least as high as the Physician.Footnote 24

As a lecturer at St George’s, Brodie may have had good reason to single out William Cheselden and John Hunter as pioneers of modern surgery, as both men were closely associated with that hospital. Brodie’s teacher, and fellow St George’s Hospital surgeon, Everard Home (1756–1832) certainly had especial reason to celebrate the latter, as he was Hunter’s brother-in-law and his former pupil, as well as the joint executor, together with Hunter’s nephew Matthew Baillie (1761–1823), of his estate. Moreover, he was the direct inheritor of Hunter’s intellectual legacy and benefited greatly from the association, although his reputation was tainted by his subsequent destruction of Hunter’s personal papers, an act that gave rise to inevitable suspicions of plagiarism.Footnote 25 In 1811, some twelve years prior to this fateful decision, Home gave a series of lectures to his students at the Great Windmill Street Anatomy School, founded by John’s older brother, William Hunter (1718–83); he chose to open in customary (and self-serving) fashion with some moral and historical instruction. ‘It is usual in beginning a course of lectures wither [sic] on Medicine or Surgery’, he announced, ‘to read an introductory Lecture, in which is given a short history of the art, its excellencies pointed out, & the sources from which the teacher derived his knowledge detailed’. He continued:

In the earlier times of physic, the art of Surgery was low and confined to the performance of manual operations, which were determined by the Physician. As the physicians professed no accurate knowledge of the structure of the human body, it was impossible that the art could be advanced under their direction. Surgery could not be improved till the practitioners had become acquainted with the different parts of the body; their use & connection with one another. With the progress of Anatomical Knowledge is to be traced the advancement of Surgery.Footnote 26

Surgery’s professional and social subordination was, then, according to Home, a direct product of the physician’s ignorance of anatomy. However, even if the necessity of anatomical knowledge for improved surgical practice had long been acknowledged, ‘the prejudices of mankind against dead bodies made it necessary that Anatomical pursuits should be followed in secret in the first instance’. This only began to change in the eighteenth century, Home alleged and, in a narrative that would become a staple of later hagiographic accounts, he held the personal achievements of the Hunters responsible for a greater national renewal:

In England, before the time of Dr Hunter, Anaty [sic] was superficially taught, & improvements in it confined to France. To the late Dr Hunter England is indebted for the rapid advancement she has since made in the Practice of Surgery. Dr Hunter not only made himself master of the anatomy of the human body but every thing concerned with that study by diligence & unwearied perseverance. His merit to his country however extended beyond these narrow limits. With infinite difficulty, notwithstanding the professional prejudices against it he instituted a practical School for Anatomical Dissections. He was hence not satisfied with being eminent himself, but desirous of making his pupils as capable as their master.Footnote 27

Home’s implication about the equivalence of master and pupil was clear enough. However, in case anyone in his audience had missed it, and to ensure that he caught the full light of the Hunters’ reflected glory, he added that his testimony was ‘a just tribute to the memory of that great man who erected the walls by which we are now surrounded & it was from him that I received my first lesson’.Footnote 28

While Home may have had a particularly close personal connection to William and John Hunter, he was far from alone in claiming a unique place for the brothers in the history of anatomy and surgery. As his lecture implies, William’s contributions to anatomical study were widely recognised by Romantic surgeons, but it was his younger brother John who, as the surgical sibling, was most commonly singled out for praise. Indeed, Stephen Jacyna has argued that he was deified by later eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century surgeons to an extent rivalled only by Isaac Newton’s (1642–1727) idolisation in natural philosophical circles.Footnote 29 According to Jacyna, unlike Newton, or indeed other celebrated figures in the history of medicine such as William Harvey (1578–1657) and even his own erstwhile apprentice, Edward Jenner (1749–1823), Hunter did not lend his name to a single discovery or therapeutic innovation. Instead, his fame rested on his wholesale transformation of surgery from a manual occupation to a scientific one.Footnote 30 As the Guy’s Hospital surgeon Astley Cooper pithily put it to his students, ‘Surgery before his time was good mechanical but after it good scientific’.Footnote 31

The principal locus for the mythologisation of John Hunter and the celebration of scientific surgery in the nineteenth century was the Hunterian Oration to the Royal College of Surgeons, established by Home and Baillie in 1813. This provided an opportunity for leading surgeons of the day to rehearse their history, and to cement Hunter’s place in it as the man who transformed surgery into a science. What is important to note is that these orators, and others who lauded Hunter’s legacy, did not celebrate the cultivation of scientific anatomy for its own sake. In a remarkable claim that swept away the achievements of Andreas Vesalius (1514–64) and Ambroise Paré (1510–90) among others, William Norris (1757–1827) stated:

since the time of the Greeks, very many ponderous volumes, of pompous title and bombastic promise, on the subjects of Anatomy and Surgery have been published; but they contained little that was of any value, save what was purloined or imperfectly translated from their predecessors. The surgery therefore which prevailed in this country, even at the beginning of the eighteenth century, except in the treatment of a few diseases, could hardly be said to be an improvement upon that of Hippocrates, 2,200 years before!Footnote 32

What was different about Hunter and his contemporaries, Norris and others proposed, was that their knowledge of anatomy and pathology was fundamentally applicable to practice. This was not the classical anatomy of the physician, concerned predominantly with structure and form, but rather a surgical anatomy, which enabled the surgeon to treat disease and injury with greater confidence and with better results for the patient. According to Norris:

This preliminary knowledge necessarily produced a more rational pathology; and that the comforts and safety to mankind from thence derived became apparent, and were properly appreciated, is seen by the high degree of estimation in which those who exercised the Art and Science of Surgery were held. The easy and effectual method of restraining haemorrhage by the ligature – the general adoption of simple and superficial applications to wounds and sores – the practice of saving as much skin as possible in operation – and even the bringing into contact the divided muscles from the opposite sides of a stump immediately after amputation, so that they occasionally unite by the first intention, are a few of the very many improvements that had taken place.Footnote 33

As we have suggested, if John Hunter became the model of the scientific surgeon for London’s practitioners in the early nineteenth century, the picture in Edinburgh was somewhat different. The reception of Hunter’s legacy in Scotland in general, and Edinburgh in particular, is a topic that invites further study. Despite being a Scot, Hunter moved to London at an early stage in his career and stayed there until his death. As such, he remained indelibly associated with England’s capital. Moreover, both brothers were born in Lanarkshire and had close ties to Glasgow. The latter was especially true of William, who studied at the university there, and it was to that institution that he left his anatomical collections after his death. Both men were therefore outside of the orbit of the Edinburgh medical and surgical elite, and neither could be comfortably assimilated into a collective narrative of Scottish surgical self-improvement.

If there was no one figure of equivalent stature to John Hunter in early nineteenth-century Edinburgh, there were a number of individuals associated with the development of surgical anatomy in that city. In his historical account of the Edinburgh anatomical school, published in 1867, John Struthers (1823–99) opens with the three generations of the Monro family who occupied the chair of anatomy at the University of Edinburgh between 1725 and 1846.Footnote 34 Alexander Monro primus (1697–1767) studied at Leiden, but did not take a degree and only received an honorary MD from Edinburgh in 1756.Footnote 35 By contrast, his son Alexander Monro secundus (1733–1817) and grandson Alexander Monro tertius (1773–1859) were both physicians and taught anatomy in a classical manner, predicated on medical rather than surgical requirements.Footnote 36 Indeed, Monro secundus actively opposed the Royal College of Surgeons’ attempts to institute a professorship of surgery, thereby ‘preventing the establishment of a course of surgery in Edinburgh for thirty years’.Footnote 37 For Struthers, then, the true ‘father’ of surgical anatomy in Edinburgh was John Bell. As he writes:

Among the crowd of students in Mono’s class-room, there was one remarkable for his keen eye, intelligent countenance, and small stature. It struck this youth that, although Monro was an excellent anatomist and teacher, the application of anatomy to surgery was neglected. He saw this opportunity and took his resolution accordingly. This was John Bell […] As Monro had never been an operating surgeon, the deficiency in his teaching would, we might suppose, be evident enough; but the merit of John Bell’s early surgical discrimination is appreciated only when we remember that there was no surgical anatomy, as now understood, in the Edinburgh school till he introduced it by himself.Footnote 38

Bell explained, in his own words, the inadequacy of a classical anatomical education for the practising surgeon:

It is an actionable and most dangerous occupation, to attempt to benefit the human race by acquiring skill, or learning anatomy, on any thing but CORK and WOOD! unless it be upon LIVING BODIES. In Dr Monro’s class, unless there be a fortunate succession of bloody murders, not three subjects are dissected in a year. On the remains of a subject fished up from the bottom of a tub of spirits, are demonstrated those delicate nerves, which are to be avoided or divided in our operations; and these are demonstrated once at the distance of one hundred feet! nerves, and arteries, which the Surgeon has to dissect, at the peril of his patient’s life.Footnote 39

Bell began lecturing in 1786, first at the College of Surgeons and then, from 1790, at his own purpose-built anatomical school in the college grounds; he soon became one of the most popular extra-mural teachers in Edinburgh. According to Struthers, ‘the position which John Bell exemplified and defended, was one which no man will now venture to dispute, that surgery must be based on anatomy and pathology, a doctrine for which there was at that time, in “the windy and wordy school of Edinburgh”, neither acceptance nor toleration’.Footnote 40 As Bell himself put it, ‘ANATOMY serves to a Surgeon, as the sole theory of his profession, and guides him in all the practice of his art’.Footnote 41

John Bell is a central figure in the development of Romantic surgery, not least, as we shall see, because he was the most articulate advocate for a surgical identity founded upon sensibility and compassion and rooted in the embodied experience of operative practice.Footnote 42 For our immediate purposes, what is important to note is that Bell’s scientific surgery, like that of John Hunter, was not only said to have transformed surgical practice in terms of its sophistication and efficacy. It was also said to have made surgeons more cautious, encouraging them to adopt a less heroic and interventionist approach to operations. Indeed, Bell, like many of his contemporaries, castigated the surgery of the past as rash and cruel, precisely because of its relative ignorance of human anatomy and pathology:

We have now leisure to observe, how slowly diseases have been understood, or operations invented or improved; we can remark how slowly and imperfectly anatomy has been applied even to this day; at this moment we are employed in rooting out the prejudices and barbarous practices of those Gothic times! For the practice of the older surgeons was marked with all kinds of violence; and indifference about the simple cure of diseases; and a passion for operations, as the cutting off of limbs, the searing of arteries, the sewing of bowels, the trepanning of sculls [sic] round and round, and all the excesses and horrors of surgery.Footnote 43

In this new age of scientific surgery, it became increasingly common for practitioners to trust to the curative powers of nature. In a lecture to his St Bartholomew’s Hospital class in October 1818, for example, John Abernethy (1764–1831) considered the treatment of inflammation:

The Question then comes, should I open the abscess? – What would be the use of it; nature is her own Surgeon, and knows better how to do it than any of us, she removes the superincumbent parts and sets up such disorder in them that they are the last to heal – but if we stick in our knives, in a short time the wound becomes united and this is the way to make a Fistula by interfering with natures [sic] processes.Footnote 44

Of course, such a transformation did not happen overnight, and many surgeons doubtless continued to intervene while others were inclined to watch and wait. ‘The truth is’, Bell wrote, reiterating his earlier point, ‘that the practices and the prejudices of the old times mix themselves with the more orderly and perfect operations of the present day’.Footnote 45 Even so, by the early decades of the nineteenth century it had become commonplace for surgeons to deprecate what Robert Liston called the ‘old meddlesome surgery’, the ‘eternal pokings and probings of wounds, abscesses, and sinuses’. ‘Nature’, he argued, ‘well and judiciously assisted, instead of being thus thwarted, tampered, and interfered with […] will generally bring matters to a speedy and happy conclusion’.Footnote 46

This increasing emphasis upon operative restraint was not simply a consequence of greater anatomical and pathological knowledge; it was also an expression of surgery’s growing professional self-confidence and of the kinds of culturally resonant identities that Romantic surgeons sought to craft for themselves. For one thing, from the later eighteenth century onwards, what Owsei Temkin famously called ‘the surgical point of view’ had become increasingly central to the ways in which medical practitioners as a whole thought about the body and disease.Footnote 47 The effects of this were felt most powerfully in France, where the Parisian clinical ‘revolution’ of the early nineteenth century was predicated on a surgical sensibility that saw disease as located in the anatomical structures of the body, and where the traditional hierarchies of medicine, which placed the physician above the surgeon, were collapsed into the figure of the officier de santé.Footnote 48 In Britain, the manifestations of this process were not quite so dramatic, but they were no less transformative. After all, the notable expansion of the medical market in this period took place not so much among the ranks of the physician as among those of the surgeon-apothecary or general practitioner. These men may have been of lower status than the physician or the ‘pure’ surgeon, and many may have endured economic insecurity, but they were, in many ways, the vital force of early nineteenth-century medicine and, as Andrew Whelpdale’s letter quoted earlier suggests, they commanded an increasing share of the market for medical services. What was notable about these men is that they were trained not as physicians, but rather as surgeons; they therefore viewed the diseased body, and the world it inhabited, through the eyes of the surgeon, albeit one acutely conscious of his subordination to the Council of the Royal College.Footnote 49

In light of this, many surgeons were increasingly overstepping the traditional boundaries of their practice.Footnote 50 This was true not simply for general practitioners, but also for those among the surgical elite. John Abernethy, for example, was celebrated as a surgical lecturer but was, by all accounts, an indifferent operator. Astley Cooper, who otherwise regarded him as ‘an amusing companion’ with ‘an excellent private character’, stated that he ‘would have made a good physician, but never was a perfect surgeon, and never would have been, had he lived a hundred years’.Footnote 51 Even his own biographer admitted that ‘we have very little desire to rest any portion of his reputation on this branch of our duty’, adding that as Abernethy ‘advanced in life, his dislike to operations increased’.Footnote 52 We shall come to consider the reasons why Abernethy so disliked the operative aspects of surgery in Chapter 2. For the moment, it will suffice to observe that his aversion to the knife may have influenced the nature of his practice, which, in line with Cooper’s observation, was very similar to that of a fashionable metropolitan physician.Footnote 53 Though his biographer was at pains to deny it, Abernethy’s lectures speak to the fact that he saw the health of the digestive system as being at the root of many disorders, and it was this belief that led him to concoct his ‘blue pill’, something that Cooper believed ‘did him harm’.Footnote 54 Even so, it would be inaccurate to conceive of Abernethy’s practice purely in terms of his praxial limitations or intellectual idiosyncrasies. Rather, his reluctance to regard surgery ‘merely as an operative art’ was part of a broader ideological commitment to uniting medicine and surgery in the management of disease.Footnote 55 Never a political radical, Abernethy nonetheless invoked the radicalism of French medicine when he famously told his students that ‘surgery and medicine are essentially, what the French Republic was declared to be, “one and indivisible”’.Footnote 56 ‘The physician must understand surgery and the surgeon the medical treatment of disease’, he informed the audience at his Hunterian Oration of 1819.Footnote 57

Even if the desire to stress competencies other than the manual can be seen as part of Romantic surgery’s designs on the sphere of medicine, it might nonetheless appear odd that surgeons of the early nineteenth century sought to distance themselves from the one aspect of their practice that rendered them unique. After all, from the middle decades of the nineteenth century onwards, surgeons were apt to emphasise their physical capacities as heroic men of action, and by the later decades, operative surgery had become, in the words of Thomas Schlich, the ‘technological fix’ for the ills of the modern body.Footnote 58 In order to make sense of this rhetorical and political strategy, it is important to reiterate that it did not constitute a wholesale repudiation of embodied skill per se. Rather, it deprecated the kind of rash and heedless operative intervention that was represented not only as the marker of a more ignorant past, but also, on occasion, as the preserve of other surgeons whose abilities and temperament one might seek to call into question. Take, for example, John Bell’s attack on the System of Surgery (1783–8) of the (unrelated) Edinburgh surgeon Benjamin Bell (1749–1806), written under the pseudonym ‘Jonathan Dawplucker’:

The difference betwixt your description and that of a bold operator, is just that which distinguishes an assassin from a brave man! You write bloodily, though not boldly: you speak not like a regular surgeon […] but like a desperate man, careless of everything, and afraid only of being affronted, or, in other words, “embarrassed” in the midst of a public exhibition! You write like one who had been often caught and entangled in difficulties from which he had no other way of disengaging himself than by a slap-dash stroke of the knife […] You are enfuriated [sic] by opposition! the words adhesion, stricture, gut, and sac, excite proportioned fury! and you exclaim, tear, cut, clip, destroy – Tear the adhesions, cut every thing; - surgery consists in cutting! and the best surgery is to cut every thing!!!Footnote 59

As this quotation suggests, Bell sought to represent his rival as a man whose operative ‘boldness’ was in actual fact a cover for vanity, anger, and incompetence. His implication was not that operative skills were unimportant; far from it. Rather, as we shall now see, Bell and others were beginning to suggest that not only were exquisite manual skills and a deep knowledge of anatomy essential to the effective practice of surgery, but so too was a particular kind of emotional disposition. Shaping a professional identity within the emotional regime of Romantic sensibility, these men sought to craft an image of the modern surgeon not simply as a cerebral and scientific practitioner, but also as a moral one: self-confident, composed, and utterly dedicated to his patient’s safety and well-being.

Embodied Knowledge, Dexterity, and the Moral Surgeon

Speaking to his surgical class at St Thomas’ Hospital in 1815, Astley Cooper defined the embodied qualities of the surgeon in a phrase that would become a veritable cliché in later years. ‘With regard to operations’, he stated, ‘a few acquisitions are necessary. It has been said that an Operator should have a[n] Eagle’s eye, a Lion’s heart and a Lady’s hand’.Footnote 60 This common proverb can be found as early as the mid-eighteenth century and, doubtless, has its origins even further back than that.Footnote 61 Even so, among his students and acolytes at least, it became closely associated with Cooper, a man widely regarded as the greatest English surgeon of the early nineteenth century and, alongside Liston, possibly the best operative surgeon of the pre-anaesthetic era. The phrase is remarkable for a number of reasons, not least the framing of haptic skill as feminine. As we shall see in Chapter 2, the culture of sensibility allowed for a more fluid gendering of surgical skill than was common in the latter part of the century, although surgery remained a resolutely masculine practice until that time.Footnote 62 What is also suggestive about it is the insight that it provides into the habitus of the Romantic surgeon: the melding of perceptual, physical, and emotional/affective qualities. We shall explore the emotional/affective aspects shortly, but first it is necessary to consider the other two dimensions.

It is notable that, in introducing these necessary qualities, Cooper refers to them as ‘acquisitions’, suggesting that they were things that could be taught and learned. This is not an unproblematic assumption. If we are to take his animal metaphor seriously, we might question whether the lion learned to be courageous or whether the eagle acquired excellent eyesight. It would surely be more accurate to suggest that these qualities (even as culturally constructed) are innate to those creatures. Certainly, there was a good deal of debate in this period about whether the true surgeon was born or made. According to an anonymous correspondent to The Lancet, the public, thinking surgery a

mere mechanical operation […] conclude that frequent practice, with a proper knowledge of anatomy, must make them perfect performers:- but this is not the case; daily practice upon a musical instrument will never make some people good players […] nor will all the opportunities of operating in an [sic] hospital make a good operator of the man who has neither the eye […] nor the dexterity of finger which are the necessary prerequisites for such a performer.Footnote 63

The St Bartholomew’s Hospital surgeon Frederic Skey (1798–1872) likewise maintained that the ‘dexterity of hand’ or ‘the power of entire command over its movements, which should be at the same time firm, but light and graceful […] can only prevail in perfection, in men naturally gifted by its possession’.Footnote 64 And yet there were few surgeons indeed who would have claimed to be perfect operators. Even Astley Cooper admitted that he was ‘never a good operator where delicacy was required’ and that ‘for the operation of cataract he was quite unfitted by nature’.Footnote 65 Cooper’s reference to surgical dexterity as being akin to the ‘lady’s hand’ offers a suggestion as to how this paradox concerning nature and nurture might be resolved. After all, it was generally assumed in this period that women had an innate propensity for delicate handicraft. And yet, women’s education (across the social spectrum) still put great store by cultivating and honing those skills.Footnote 66 By the same token, it might be assumed that an aspirant surgeon, even one possessed of the natural gifts of good eyesight and dextrous hands, would still need to be trained in order to realise their potential. As John Bell put it, ‘Though the qualifications of a surgeon are not to be acquired, yet assuredly they may be improved’.Footnote 67

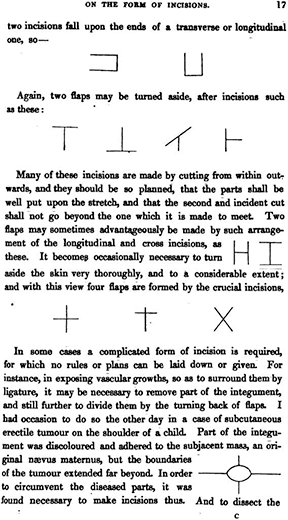

Unfortunately for the historian, the sources of embodied surgical education are not readily accessible, and it remains difficult for us to fully grasp, using the conventional materials of historical research, the exquisite haptic repertoire of Romantic surgical performance, or the ways in which those skills were inculcated in the novice. As Mark Jenner and Bertrand Taithe have argued, ‘Professional historians are deeply suspicious of modes of representation based upon bodily practices such as those followed by re-enactment societies’ and ‘rarely seek theatrically to recapture and master the manipulative techniques, the precision of hand, and other non-verbal embodied skills which were at the core of much medical practice’.Footnote 68 However, if many of the praxial dimensions of surgical education remain lost to posterity (at least in terms of their depth and sophistication), we can nonetheless appreciate something of the importance of manual training to surgical practice through what textual forms are available to us. After all, most surgeons offered at least some basic advice in their lectures on the correct way of handling the knife, and of making incisions. It should perhaps come as no surprise, given his reputation in the operative dimensions of surgery, that one of the fullest such accounts can be found in the works of Robert Liston, notably his Practical Surgery (1837). This offered a reasonably compressive guide to operative technique, even within the constraints of the textual form (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Haptic hieroglyphics: Robert Liston’s guide to incisions from his Practical Surgery (London: John Churchill, 1837), p. 17.

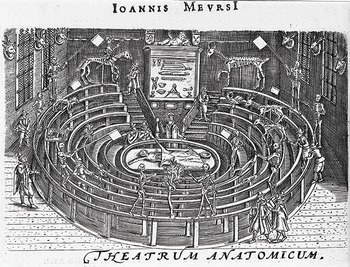

Nevertheless, the principal lesson that such written accounts taught the student of surgery was that operative skills could be acquired only by doing, not reading. According to Charles Bell, ‘words alone will never inform the young Surgeon of the things most necessary to a safe operation’.Footnote 69 For Astley Cooper, then, ‘the first object to become a good Surgeon is anatomy’, for ‘a person may operate well without it, but it is only by chance’.Footnote 70 In order to learn anatomy, as we have heard, students conventionally attended lectures in which the forms and functions of the body might be elucidated, either through illustrations and preparations or the dissection of a corpse by an anatomical demonstrator (Figure 1.2). However, by the early nineteenth century the dictates of surgical anatomy, such as practised by John Bell in Edinburgh and in the private medical schools of London, ensured that students were increasingly provided access to their own (often illicitly acquired) corpses.Footnote 71 Such forms of hands-on dissection were deemed increasingly essential to the training of operative surgeons, and specialist publications such as The London Dissector (1811) sought to guide the student through the process. ‘Dexterity in the manual operation of dissection’, it argued, ‘can only be acquired by practice’:

This species of knowledge will afford him the most essential assistance in his future operations on the living subject; in which indeed it is so necessary that we are perfectly astonished to see persons rash enough to use the knife without possessing this information; but we view the hesitation, confusion, and blunders by which such operators betray their ignorance to the bystander, as the natural result, and the well-merited but too light punishment, of such criminal temerity.Footnote 72

By dissecting the dead human form, then, aspirant surgeons might familiarise themselves not only with the anatomy of the body, but also with its haptic presence, the resistance provided by flesh and bone to knife and saw. They might also guard against future disgrace. Dissection, according to John Bell,

gives a dexterity of hand, and acuteness of sight; a manner of searching for and seizing, with the most delicate of hooks and other instruments, parts almost invisible to one not trained to dissection: And that dexterity and acuteness of sight, gives presence of mind in the moment of operation […] [it] renders scenes of danger familiar by anticipation; and inspires by degrees that address and courage, which enables a Surgeon to bear up undismayed, against alarms and accidents, when his own reputation is at stake; and, what is more distracting, while the life of a fellow-creature is endangered: Of a fellow-creature who has, at his suggestion, submitted to a dangerous operation, and is fainting in his hands, from pain and loss of blood.Footnote 73

Figure 1.2 Robert Blemmel Schnebbelie, A Lecture at the Hunterian Anatomy School, Great Windmill Street, London, watercolour (1839).

Bell’s comments, and those of the London Dissector, are notable for their deployment of emotion: their evocation of the tribulations and anxieties of operative surgery, and of the personal costs of failure, especially in front of an audience. This should come as little surprise. After all, while it might promote familiarity with the intricacies of the human frame and the use of surgical instruments, the dissection of a dead body (or even ten dead bodies, for that matter) could never truly prepare the student for the realities of operating upon a living, breathing, writhing patient. Surgical pupils were therefore encouraged to attend operations by eminent practitioners and become acquainted with the realities of operative practice. For example, Home stated that the student ‘should add to his own information by the practice of others. Public Hospitals are so many Seminaries for this part of Education, whose Operations are performed under all circumstances & varied according to the Knowledge & dexterity of the Surgeons’.Footnote 74 Students might even gain direct personal experience by paying to assist in operations, a position known as a ‘dresser’. Nonetheless, it was perfectly common to qualify as a surgeon without ever having performed an operation, let alone a capital procedure such as amputation or lithotomy.

In her ethnographic study of contemporary American surgical education, Rachel Prentice states that ‘Surgeons must teach both skills and meaning’. Most of the surgeons she worked with spoke of technical skill as constituting a mere 20 per cent of surgical education, ‘falling lower in importance than difficult-to-quantify qualities of wisdom, judgement and experience’.Footnote 75 Such was also the case for the early nineteenth century. Indeed, confronted by the prospect of a sentient patient in extraordinary pain, such considerations were even more important. Thus, Astley Cooper claimed that ‘the quality which is considered of the highest order in surgical operations, is self-possession; the head must always direct the hand, otherwise the operator is unfit to discover an effectual remedy for unforeseen accidents that may occur in his practice’.Footnote 76 Over thirty years later, Frederic Skey’s advice was similar: ‘He should possess great firmness of purpose […] to be acquired only by previous thought and preparation, and a self-possession which no accident, however unlooked for, can disturb or alienate’.Footnote 77

At one level, this emphasis upon self-possession was a reaction to the practical challenges of pre-anaesthetic surgery. But it was also much more than this. In the early nineteenth century, surgical lecturers increasingly emphasised the moral and emotional aspects of the surgical persona, in contradistinction to the traditional emphasis on manipulative skill and operative dexterity. ‘If I were to judge of a Surgeon’s abilities’, Cooper told his students, ‘I would not judge him by his manner of performing the operation for the stone or the amputation of a limb, but would form my opinion of him according as he possesses a power of encountering unexpected dangers with calmness. It is this quality above all others […] which you should endeavour to make yourselves masters of’.Footnote 78 In delivering his Hunterian Oration in 1826, meanwhile, the Westminster Hospital surgeon Anthony Carlisle (1768–1840) argued that ‘The operative practice of surgery is a mere mechanical art’ and that ‘if it be exercised with daring temerity, unchecked by moral or by scientific reflection, it becomes a desperate if not a mischievous calling’. The ‘vain pretender brandishing his knife over the affrighted victims of his violence, may become a popular surgeon’, he claimed, ‘and by early good luck may reach his way to vulgar fame; but his career is most dangerous, and the result unenviable’.Footnote 79

Frederic Skey was similarly sensitive to this delicate balance between the moral and manual qualities of surgery. ‘To write a work on Operative Surgery, which should consist of merely mechanical rules for the performance of an amputation’, he observed:

would be to leave the work more than half unfinished, simply because the knowledge, which determines the necessity of the undertaking is far more valuable […] than that which is required to qualify a surgeon for its performance. The one qualification involves both the moral feeling and intellect of the surgeon. The other demands the exercise of his physical functions onlyFootnote 80

This ‘moral feeling’, Skey maintained, ‘is more involved in the establishment of a just reputation than the world at large imagines’.Footnote 81 This was because the operating surgeon was ‘not a mechanic, but the agent through whose instrumentality is carried into action the highest principles of scientific medicine’.Footnote 82 Skey’s sense of the primacy of ‘moral feeling’ over manual skill was such that, even in a book dedicated to the subject of operations, he proclaimed:

I have endeavoured as an English metropolitan surgeon to carry into execution at least one primary object, viz., to strip the science of Operative Surgery of a false glare, mistaken by the ignorant for the brightness of real excellence, to check a spirit of reckless experiment and to repress rather than encourage the resort to the knife as a remedial agent.Footnote 83

Operative Surgery (1850) was published only a few years after the introduction of ether and chloroform, but it was fundamentally a product of the pre-anaesthetic era; Skey had studied under John Abernethy and his career had been forged in the 1820s. Indeed, Skey’s distrust of what he called the ‘brilliancy’ and ‘éclat’ of operative performance had deep roots in the cultures of Romantic surgery, which can be traced back to John Bell. Bell’s elaboration of a Romantic surgical persona at the turn of the nineteenth century was shaped by contemporary anxieties about the dangers of artifice and the importance of emotional sincerity and personal authenticity.Footnote 84 For Bell, the truly authentic surgical man of feeling rejected ostentation, artifice, and self-promotion in favour of a selfless and compassionate dedication to his patient’s well-being. Thus, in his Principles of Surgery (1801) he argued that ‘boldness is a seducing word, and the passion of acquiring character in operations is surely full of danger’. ‘We are but too apt’, he continued, ‘to allow the audax in periculis [boldness in danger] to be the character of a good surgeon. But this is a temper of mind and a line of conduct which can benefit nothing but the character of the surgeon himself; for as to his patient, this shameless thirst of fame! this unprincipled ambition, is full of danger’. In place of such self-centred exhibitionism, Bell proposed the following:

Should not then the present suffering of the patient, and sense of his own duty, and above all the trust that is reposed in him, occupy the surgeon’s mind too much to leave room for vain or selfish thoughts? Yet we every day see surgeons cutting out harmless tumours with affected and cruel deliberation, and in the same hour plunging a gorget among the viscera with unrelenting harshness.

Believe me, those qualities which relate to operations and other public exhibitions of skill, are of a very doubtful kind, while the duties of humanity and diligence are far more to be prized; they are both more amiable and more useful.Footnote 85

According to Bell, then, operative flair was not simply an affectation that, in many cases, concealed as much as it revealed; it was a morally repugnant act that put the practitioner’s desire for esteem ahead of his patient’s interests. Charles Bell certainly inherited his brother’s sensibility in this, as in many things, writing that ‘Any thing [sic] like a flourish on such an occasion, does not merely betray vanity, but a lamentable want of just feeling. It is as if a man said – Look at me now – see how unconcerned I am, while the patient is suffering under my hand!’Footnote 86 Moreover, John Bell’s arguments had a lasting impact far beyond his own family. John Struthers praised the Principles of Surgery as an ‘undying book’, while The Lancet claimed that it ‘may be fairly considered the most interesting, if not the most useful, that has ever appeared on the subject of surgery […] a work which may make a man proud of his calling’.Footnote 87 Indeed, if Skey’s comments suggest something of Bell’s influence, in other cases the intellectual inheritance was even clearer. For example, in lecturing to his students at the Aldersgate Street Medical School in the early 1830s, James Wardrop (1782–1869) quoted directly from the above passage of ‘the late Mr John Bell’ before adding his own coda:

Some of you may have heard of instances where surgeons, in other respects deservedly eminent, forgetting the duties of civilized life, have attempted a kind of theatrical effect in performing operations, for no other purpose than to give bystanders a false impression of their dexterity, coolness, and presence of mind […] that affectation of dexterity, or doing operations quickly, is but a pitiful ambition in those who use it […] but you will invariably observe that none except those who are deficient in moral courage […] find it necessary to resort to such conduct; and that a man who feels himself equal to the task he undertakes proceeds deliberately and calmly, steadily bearing in mind the grand object – relief to the patient.Footnote 88

Clearly, then, Romantic surgical culture militated against the idea of excessive, ostentatious, and unrestrained operative display. However, the very fact that surgical writers and lecturers of the early nineteenth century felt the need to caution against flamboyance and theatricality hints at another important dimension of operative practice. We have already heard from publications such as The London Dissector that surgery was often performed in front of an audience and that surgical skill was increasingly subject to scrutiny. Now we shall discover that this ‘public’ quality had profound implications for surgical performance, both literal and metaphorical.

The Operating Theatre as Performative and Emotional Space

The nineteenth-century Scottish author John Brown (1810–82) is now not much remembered. But in his lifetime he was a celebrated essayist and man of letters and was invariably mentioned in conjunction with his most well-known story, Rab and His Friends (1859). Essentially a paean to the nobility of dogs, this is a semi-autobiographical work in which surgery plays a central role.Footnote 89 Brown studied surgery in Edinburgh in the late 1820s, was apprenticed to James Syme, and served as a dresser and assistant at Syme’s Minto House Hospital.Footnote 90 The story begins in 1825 with Brown as a teenage boy witnessing Rab, a large grey mastiff, kill a crazed bull terrier on the Cowgate. It resumes six years later with Brown a student at Minto House. He is now close to Rab and is acquainted with the dog’s owner, a simple carter by the aptronymous name of James Noble. One day, James brings his wife, Ailie, to the hospital with what he refers to as ‘trouble in her breest [sic]’. On examination, her breast is found to be ‘hard as stone, a centre of horrid pain’, and Syme opines that the advanced nature of the cancer means that she must be operated on urgently.Footnote 91

The operation takes place the following day and the students, eager to witness the procedure, rush into the theatre. ‘Don’t think them heartless’, Brown cautions his readers; ‘they are neither better nor worse than you or I; they get over their professional horrors, and into their proper work – and in them pity – as an emotion, ending in itself or at best in tears […] lessens, while pity as a motive is quickened’. ‘The operating theatre is crowded’, he continues;

much talk and fun, and all the cordiality and stir of youth. The surgeon with his staff of assistants is there. In comes Ailie: one look at her quiets and abates the eager students. That beautiful old woman is too much for them […] These rough boys feel the power of her presence […] The operation was at once begun; it was of necessity slow; and chloroform – one of God’s best gifts to his suffering children – was then unknown. The surgeon did his work […] [Finally] it is over: she is dressed, steps gently and decently down from the table, looks for James; then turning to the surgeon and the students, she courtesies, – and in a low, clear voice, begs their pardon if she has behaved ill. The students – all of us – wept like children.Footnote 92

Brown’s story provides a linking thread between the conventions of Victorian sentimentality and those of Romantic sensibility, linkages that are now increasingly recognised by historians.Footnote 93 Even so, it explicitly represents a pre-anaesthetic emotional regime in which the sufferings of the patient constituted a moral drama at the heart of surgical performance. Brown begins by asking his readers not to judge his fellow students for their enthusiasm or jocularity, suggesting that emotional restraint is a central aspect of surgical character and education. And yet, when confronted by the nobility of this woman, they are moved, ultimately, to tears. Neither is it just the students who express emotion. Syme himself is recorded as addressing Ailie in ‘a kind way, pitying her through his eyes’.Footnote 94 This is not incidental. Such affective engagement is central to the story’s purpose, for as Brown notes, ‘there is a pleasure, one of the strangest and strongest in our nature, in imaginative suffering with and for others’.Footnote 95

As we shall see, Brown’s representation of the emotional and moral politics of the pre-anaesthetic operating theatre was an idealised one. Nevertheless, it captures something vital about this space as one of noise, confusion, and occasionally irreverence, which had, somehow, to be managed and disciplined. It also reminds us of the theatrical aspects of surgery in this period. Romantic surgery was not only an intense drama, it also often had a stage and actors, as well as an audience. In Chapter 4, we shall consider in more detail the ways in which a theatricalised sensibility shaped the radical scrutiny of surgical practice. For the moment, we are concerned with the general cultures of the operating theatre and its impact on surgical performance.

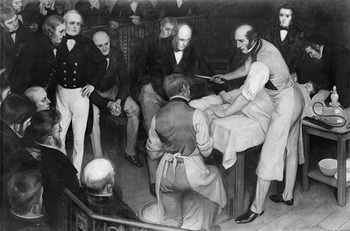

Before considering the theatrical dimensions of Romantic surgery, it is important to note that many operative procedures in this period were undertaken in private residences by fee-paying patients. Aside from the occasional textual reference, or images such as the well-known 1817 watercolour of an operation to remove a tumour, undertaken in the otherwise salubrious surrounds of a Dublin drawing room (Figure 1.3), we know relatively little about how such homes were arranged, or rearranged, for the purposes of medical and surgical procedure. By contrast, we know rather more about how the operative spaces of public institutions were appointed. Most hospitals, including small provincial ones, had some kind of discrete space for the performance of operations. With the expansion of surgical education in the later decades of the eighteenth century, however, teaching hospitals, such as those in London, built larger rooms to accommodate students. Few operating theatres from this period survive. The best example in Britain is that of the old St Thomas’ Hospital, originally built in 1822 before being rediscovered and partially reconstructed in the late 1950s. From this survival, as well as from contemporary sources, we know that operating theatres of the period traced their spatial lineage back to the anatomical theatres of the Renaissance.Footnote 96 The oldest of these was built at Padua in 1594, followed by a similar structure at Leiden in 1596 (Figure 1.4). As Jonathan Sawday observes, these spaces ‘combined elements from a number of different sources, drawing together different kinds of public space in order to produce an event that was visually spectacular’. ‘In the construction of these theatres’, he states, ‘we can discern outlines of the judicial court, the dramatic stage, and, most strikingly, the basilica-style church or temple’.Footnote 97 What is perhaps most characteristic about these structures is their steep terraced sides, often with a balustrade and handrails to allow the audience to gain as unobstructed a view as possible. Enhancing the visuality of the proceedings was not simply about observation, however. The spatial arrangement of the theatre also focused the audience on the moral dimensions of the performance. In her work on the anatomical demonstrations of Alexander Monro primus, Anita Guerrini coins the term ‘moral theatre’ to describe the ways in which anatomical dissection functioned as a ‘public performance intended to induce in its audience such emotions as awe, fear, and compassion – emotions similar to those provoked by religious practices’.Footnote 98

Figure 1.3 ‘A surgical operation to remove a malignant tumour from a man’s left breast and armpit in a Dublin drawing room’, watercolour (1817).

Figure 1.4 Leiden anatomical theatre (1596), from Johannes van Meurs, Athenae Batavae (1625).

However, while the operating theatre of the early nineteenth century had its antecedents in the anatomical theatres of the Renaissance, they were not identical structures. Most operating theatres built in this period had a more proscenium than amphitheatrical quality, with the audience facing the ‘stage’, so to speak, more or less front on (Figure 1.5). In part, this reflected wider shifts in theatrical architecture, but it also coincided with a fundamental shift in purpose. Early modern anatomical dissection was, to a great extent, a public spectacle. Artists attended to view the form and articulation of the body, while others sought spiritual succour in the wonders of divine creation. By the early nineteenth century, however, routine public anatomical demonstrations had all but died out. Such practices increasingly moved behind closed doors as their rationale shifted from quasi-religious revelation to utilitarian medical education. The same is true of the operating theatre. These spaces were located in hospitals, which, during the course of this period, were transitioning from quasi-public civic spaces into professional institutions dedicated to the construction and dissemination of medical knowledge.Footnote 99 Members of the public occasionally continued to attend operations in the first half of the century, but there was a growing consensus that these were professional spaces that should be accessible only to practitioners and students.

Figure 1.5 F. M. Harvey, The Old Operating Theatre at The London Hospital, Demolished in 1889 (1889), oil on canvas.

To say that the early nineteenth-century operating theatre was a more tightly policed space than its forebears is not to say that it was any less moral or dramatic. Indeed, one might say that, as the space was shorn of its spiritual connotations, it became ever more akin to a theatre in the literal sense. In almost all the hospitals of the metropolis, it was necessary to be either a practitioner, or a student in possession of a ticket, in order to attend an operation. The behaviour of this audience also resonated with the experience of play-going. The St Thomas’ Hospital surgeon John Flint South recalled that, as a young student:

The operation day was Friday, and in the earlier part of my hospital life it was very rare to have less than two or three operations. The operating theatre was small, and the rush and scuffle to get a place was not unlike that for a seat in the pit or gallery of a dramatic theatre; and when one was lucky enough to get a place, the crowding and squeezing was oftentimes unbearable, more especially when any very important operation was expected to be performed.Footnote 100

Chaotic though such scenes might appear, there was, in principle at least, a semblance of order. Generally speaking, the space immediately around the table was occupied by the surgeon, his assistants, and dressers. The seats closest to the front were reserved for the house surgeons and eminent visitors, while those behind were taken up by fee-paying students. Other, less prestigious visitors, meanwhile, were relegated to the back. These arrangements were subject to a delicate politics. In 1844, for example, Joseph Rogers (1820–89) decided to attend an amputation of the thigh undertaken by James Moncrieff Arnott (1794–1885) at his alma mater, the Middlesex Hospital. On entering the theatre, he ‘walked into the front row, where I found two old pupils, like myself’ and was reassured by a notice ‘to the effect that former house-surgeons, old pupils who came as visitors, and the dressers to the other surgeons, were allowed to stand there’. However, on entering the theatre, Arnott ‘turned upon me, saying […] “You have no business here – go out”’. Humiliated, Rogers ‘withdrew, (observing as I went, “I am an old pupil”,) and then took my station at the top of the theatre, amidst the tittering of the students who doubtless thought me an intruder’.Footnote 101

In many ways, the atmosphere of the operating theatre was in keeping with the broader cultures of medical student life, as described by Keir Waddington and Laura Kelly.Footnote 102 Concern about student behaviour, according to Waddington, ‘fed on a rich vein of anxiety about moral decay, crime, and intemperance associated with urbanization […] [and] its visible display of playhouses, pleasure gardens [and] prostitutes’.Footnote 103 For the most part, however, it resembled little more than schoolboy pranks or the limited licence of the apprentice. Thus, in 1823 a former Edinburgh student complained to The Lancet about the conduct of those awaiting Astley Cooper’s lecture at St Thomas’ Hospital. ‘What an interesting spectacle’, he wrote, ‘to see a body of young men assembled for the purpose of acquiring professional knowledge, actively engaged in discharging masticated paper and apple into each other’s faces; or employed in the no less intellectual occupation of twirling around the Lecturer’s table, or sprinkling dirt on the heads of those who happen to sit under them’.Footnote 104 At other times such rowdiness could serve more political ends, as students sought to defend their perceived rights and interests. This was especially notable in the aftermath of the acrimonious collapse of the so-called United School of Guy’s and St Thomas’ in 1825.Footnote 105 Bransby Cooper (1782–1853), Astley Cooper’s nephew and protégé, had been appointed professor of anatomy to the new school at Guy’s and when he attempted to attend a lithotomy at St Thomas’, undertaken by Joseph Henry Green (1791–1863), he was forced ‘out again immediately, several of the pupils having expressed their disapprobation of his presence by hisses’.Footnote 106

Much of the time, the disordered scenes in metropolitan operating theatres were merely the product of students endeavouring to get the best possible return on their fees. In 1828, a pupil at St George’s Hospital wrote to The Lancet complaining that

I have heard, occasionally, the voice of the surgeon as he addresses the patient; I have seen, occasionally, the gleam of the knife in the operating theatre of this establishment, and have been electrified by the scream of the patient, and edified by the remonstrating voice of the surgeon; but I have rarely seen or heard more […] I have never had a fair and distinct view of an operation on the regular day of operating, since I have had the happiness of being attached to this establishment. That portion of the theatre where the patient is placed, is, upon the arrival of the operating surgeon, instantly filled by friends, dressers, surgeons, house surgeons, etc.; all these literally club their sagacious heads together, and – but need I say more? the pupils in the first row endeavour to overtop them, those in the second or third row follow their example, and the rest are under the necessity of standing on the rails, bars, posts, etc. to obtain a casual glance at what is going forward.Footnote 107

With its reference to the electrifying ‘scream of the patient’, this letter reminds us of the intense pathos at the heart of such scenes. Likewise, another correspondent evoked the ‘weeping and cries’ of Mary Hayward, a 25-year-old woman who had come to St Bartholomew’s to have a tumour removed from her knee. In the midst of the procedure she pleaded with the operator, imploring him to ‘“let it alone, let it alone! don’t pull it about any more […] plaster it up! I won’t let you cut it any more, I won’t, I won’t, I won’t”’. These expressions were combined with ‘cries of “heads! heads!”’ from the back of the theatre as the students endeavoured to catch sight of proceedings, followed by hisses when their requests were ignored. It was, according to the correspondent, an unedifying scene that ‘entirely did away with the ordinary view and benefit derived from the performance of operations in this theatre’.Footnote 108 Needless to say, many commentators were aware that such an atmosphere can have done little to improve the patient’s emotional state. Writing to The Lancet in 1827, for example, a student at the Borough hospitals of Guy’s and St Thomas’ argued that ‘The mode in which operations were conducted at both hospitals was shameful’ and that ‘during the performance of the operation there was a continual cry of “hats off, heads”, etc., which was not only annoying to the more gentlemanly students, but also tended to render the patient more fearful’.Footnote 109

We shall see in Chapter 2 how surgeons sought to render the experience of operations more emotionally palatable to the patient, and in Chapter 4 we will consider the political consequences of their failure to do so adequately. For the moment, however, it is important to recognise that the atmosphere of the operating theatre also had a profound impact on surgical conduct. For one thing, the audience members did not always limit themselves to watching the procedure or interacting only with each other. As with the contemporary dramatic theatre, which had yet to be ‘rationalised’ by the efforts of reformers and the effects of the Theatres Act of 1843, there was often a permeable boundary between ‘pit’ and ‘stage’.Footnote 110 In an incident at St Bartholomew’s in 1834, for example, Eusebius Lloyd (1795–1862) and William Lawrence (1783–1867) were tying an arterial aneurysm when they were surrounded by several other surgeons, one of whom ‘actually took the knife and forceps from MR. LLOYD’S hand and proceed coolly to satisfy his doubts by actual dissection’.Footnote 111 Such direct interference was rare and greatly frowned upon. Nonetheless, the routine throng of participants and observers could be intensely distracting, as in the case of Mary Hayward’s operation, where the crowd around the operator was such that he was forced to ‘raise his head and shoulders above those of others (thus indecorously conducting themselves) to perform parts of the operation with his arms completely extended before him’, or in another instance at Guy’s where an actual fight broke out between a pupil and a dresser over the former’s obstructed view.Footnote 112

In light of this, it is perhaps unsurprising that the Romantic ideal of operative performance should involve calm and considered deportment. Surgery was always a challenging affair, full of risks and unforeseen eventualities, but in as intense an atmosphere as the hospital operating theatre, there was all the more necessity to practice with a focused precision, unperturbed by the goings-on around. Moreover, one’s actions were subject to constant scrutiny by the audience, even down to the smallest gesture. As such, operators were discouraged from talking to their assistants unless absolutely necessary, directing their actions with nothing more conspicuous than a discreet glance or motion of the hand. At one level, while it might not necessarily accord with the conventional image of the pre-anaesthetic surgeon as a flamboyant showman, this cool-headedness was, as Stephanie Snow has suggested, a form of showmanship in itself:

By the late 1840s, ‘modern’ surgeons had constructed their professional identity upon attributes such as coolness and decisiveness. It was an image with elements of showmanship; the surgeon was the oasis of authority among the bodily confusion of severed flesh and bones, and the disarray of minds.Footnote 113

There is much truth in this statement, but there is also much more to be said, for, as we have suggested, by practising with a self-contained composure, operative surgeons not only demonstrated their intellectual and praxial authority, they also set a moral example, disciplining and ennobling their audience through calm and measured dedication to the patient’s well-being. As John Bell argued earlier in the century:

A man of science never proceeds without due reflection: The whole plan of his operation is perfect in his own mind: He communes with his assistant rather by signs than words, and his manner commands that stillness which is due to a moment of suffering, and essential to his self‐possession and success: He is formed by education, and qualified, from the first moment in which he takes those public duties upon him, to give impressive lessons to the younger members of the profession: They are awe‐struck with the first horrors of incisions and blood, but depart with gratified feelings, when they see the scene closed with entire relief to the sufferer, and happy prospect of success; and they learn to love and respect their profession, and to study it with emulation.Footnote 114

In this way, even the conventional signifiers of public and professional approbation were to be discouraged. In 1835, for example, The Lancet, commenting on the lithotomy of a 6-year-old child at Westminster Hospital, stated:

We are sorry to have to animadvert on the bad taste which has lately been frequently exhibited amongst the visitors at this theatre, and exemplified in the highly injudicious practice of applauding the operator in the course or at the conclusion of his labours […] Even putting out of sight the inhumanity of such demonstrations at a time when the patient is writhing in acute agony, the ill effect which any expression of feeling by an assembly must produce upon the nerves of the most intrepid surgeon at a critical moment, must be obvious to every reflecting mind, superadding, as it does, to the natural difficulty of the surgeon’s duty, the intense excitement of a public exhibition.Footnote 115

On occasion, the surgeon was even required to exercise a vocal emotional and moral authority over the space of the operating theatre. Generally speaking, surgeons were discouraged from addressing the audience, or offering instruction, until after the operation was over and the patient removed. A remarkable exception to this took place at St Bartholomew’s where William Lawrence, having amputated the cancerous penis of a 60-year-old man, ‘turned his back to the patient, and immediately began dissecting the part that had been removed’. Upon this, ‘the poor man raised himself up, took the handkerchief from his eyes, and was permitted to sit looking over the dissector’s shoulder for four minutes’. ‘At length’, the patient requested to know ‘what was to be the fate of this once important part’, to which Lawrence replied, ‘“Oh! It shall be taken care of, my friend, it shall be taken care of”’, a comment that ‘occasioned much laughter throughout the theatre’.Footnote 116

Doubtless, on this occasion the degree of jocularity permitted to Lawrence and his audience stemmed from the patient’s age and gender, as well as his active participation in the process. But in other instances, where the politics of sensibility demanded due reverence to suffering, especially that of women and children, the ‘voice of the surgeon’, as the St George’s correspondent quoted earlier put it, was to be edifying and remonstrative. In 1831, for example, during an operation to remove a tumour from the neck of a young boy, Joseph Henry Green admonished his rowdy audience at St Thomas’, telling them that ‘I am astonished that any set of persons calling themselves gentlemen should pass their jokes in this place, especially when a human being is suffering, putting myself out of the question, though I am not likely to perform a nice and delicate dissection the better by hearing such noises’.Footnote 117 Likewise, in 1840, Robert Liston had just commenced an operation to remove a piece of necrosed bone from the heel of a child at University College Hospital when

a person in the theatre, because the poor little sufferer began to cry, burst out into a loud laugh; whereupon Mr. LISTON instantly turned round, and asked, “if the offender belonged to that hospital?” He then remarked that “such unfeeling conduct was disgusting and disgraceful in the extreme.” The honourable gentleman also alluded, in strong terms of reprehension, to a similar exhibition of cruel misbehaviour a few days since […] This well-timed and excellent rebuke appeared to give great satisfaction to the gentlemen present. The operation was quickly executed, in Mr LISTON’S admirable and unrivalled style.Footnote 118

While this scene offers a stark contrast to Brown’s idealised representation of the emotional dynamics of the operating theatre in Rab and His Friends, it nonetheless presents Liston as a model of the Romantic surgeon, performing with great skill while also exercising moral authority and demonstrating a compassionate concern for his patient’s well-being in the face of callous indifference to suffering. However, as we shall see in the final section of this chapter, Liston’s reputation was not always so straightforward and serves as a reminder of the complexity and ambiguities of Romantic surgical culture.

Robert Liston: The Making of an Ambivalent Icon