Book contents

- English Convents in Catholic Europe, c. 1600–1800

- English Convents in Catholic Europe, c. 1600–1800

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Recruitment: Familial and Clerical Patronage

- 2 Embracing Enclosure

- 3 Material Religious Culture

- 4 Financing the Conventual Movement

- 5 Liturgical Life: Relics and Martyrdom

- 6 Networked: The Convents and the World of Catholic Exile

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

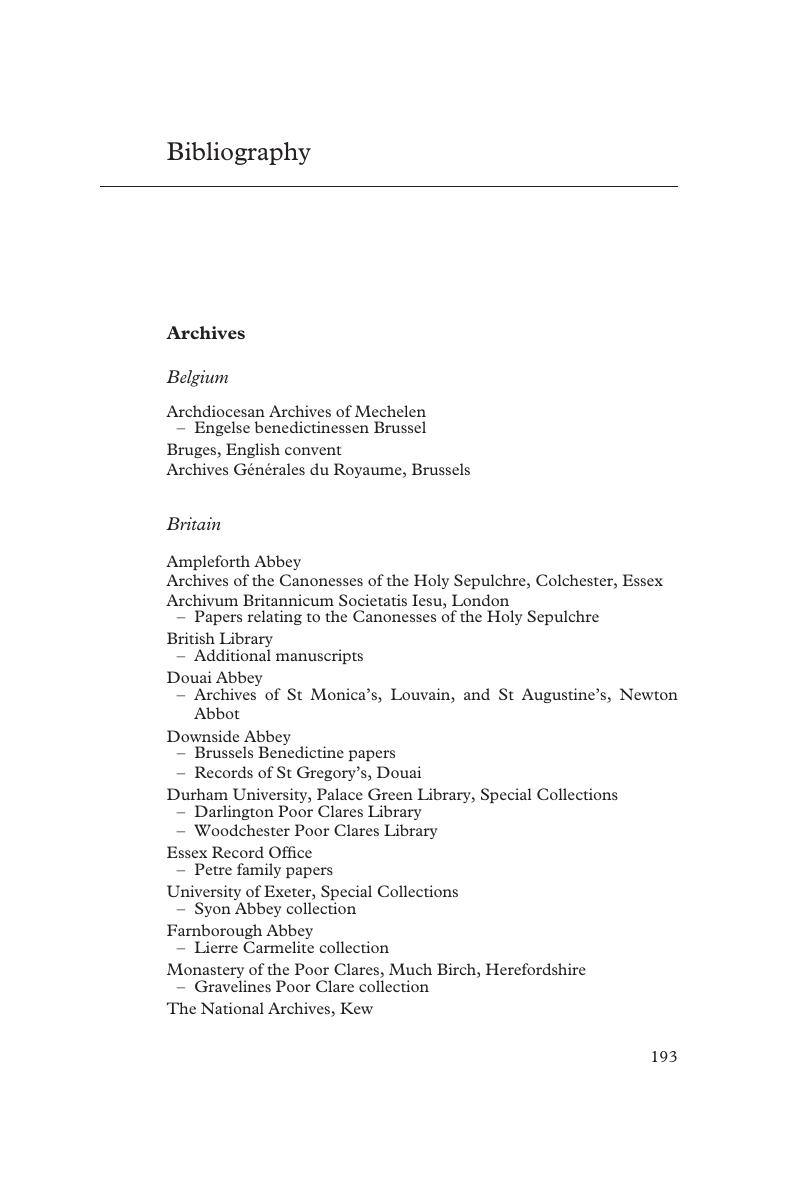

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 December 2019

- English Convents in Catholic Europe, c. 1600–1800

- English Convents in Catholic Europe, c. 1600–1800

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Recruitment: Familial and Clerical Patronage

- 2 Embracing Enclosure

- 3 Material Religious Culture

- 4 Financing the Conventual Movement

- 5 Liturgical Life: Relics and Martyrdom

- 6 Networked: The Convents and the World of Catholic Exile

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- English Convents in Catholic Europe, c.1600–1800 , pp. 193 - 213Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020