Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Glossary

- 1 JUG: Scarborough, Yorkshire, c. 1250–1300

- 2 DRINKING POT: probably English, c. 1545–60

- 3 FLAGON: probably Derbyshire or Staffordshire, c. 1630–60

- 4 BOTTLE: Christian Wilhelm, Southwark, 1628

- 5 DISH: Southwark, 1651

- 6 JUG: probably Harlow, Essex, c. 1630–60

- 7 TWO-HANDLED TYG: probably Henry Ifield, Wrotham, Kent, 1668

- 8 TULIP CHARGER: London, 1661

- 9 ‘NOBODY’: London, 1675

- 10 DISH: Thomas Toft, Staffordshire, c. 1662–85

- 11 POSSET POT AND SALVER: London or Bristol, 1685 and 1686

- 12 CISTERN: London, perhaps Norfolk House, Lambeth, c. 1680–1700

- 13 BOTTLE: John Dwight, Fulham, c. 1689–94

- 14 MUG: David and John Phillip Elers, probably Bradwell Wood, Staffordshire, c. 1691–8

- 15 JUG: Staffordshire c. 1680–1710

- 16 COVERED CUP WITH FOUR HANDLES AND A WHISTLE: probably South Wiltshire, 1718

- 17 DISH: Samuel Malkin, Burslem, c. 1720–30

- 18 SIX CHINOISERIE TILES: Bristol or London, c. 1720–50

- 19 PUNCH BOWL AND COVER: Liverpool, 1724

- 20 HUNTING MUG: probably Vauxhall Pottery, 1730

- 21 TWO-HANDLED LOVING CUP: probably Nottingham or Crich, 1739

- 22 MILK JUG AND TEAPOT: Staffordshire, c. 1725–45 and c. 1740–50

- 23 PEW GROUP: Staffordshire, c. 1740–50

- 24 BEAR JUG OR JAR: Staffordshire, c. 1740–70

- 25 CAMEL AND MONKEY OR SQUIRREL TEAPOTS: Staffordshire, c. 1750–5

- 26 JUG: Staffordshire, c. 1755–65

- 27 DISH: Liverpool, c. 1755–60

- 28 TEABOWL, SAUCER AND COFFEE POT: Staffordshire, c. 1750–65

- 29 COFFEE POT: Staffordshire, 1760

- 30 TEAPOT: probably Josiah Wedgwood, Burslem, c. 1759–66

- 31 TUREEN: Staffordshire, c. 1760–5

- 32 TEAPOT: Josiah Wedgwood, Etruria, printed in Liverpool by Guy Green, c. 1775–80

- 33 JUG: Yorkshire, 1780

- 34 CENTREPIECE: probably Leeds Pottery, Yorkshire, c. 1780–1800

- 35 STGEORGE AND THE DRAGON: Staffordshire, c. 1780–1800

- 36 TOBY JUG: c. 1790–1810

- 37 DEMOSTHENES: Enoch Wood, Burslem, c. 1790–1810

- 38 ERASMUS DARWINS PORTLAND VASE COPY: Josiah Wedgwood, Etruria, Staffordshire, c. 1789–90

- 39 TEAPOT: probably Sowter & Co., Mexborough, Yorkshire, c. 1800–11

- 40 OBELISK: Bristol Pottery, Temple Back, Bristol, 1802

- 41 DINNER PLATE: Spode, Stoke-on-Trent, c. 1806–33

- 42 GARNITURE OF FIVE COVERED VASES: Richard Woolley, Lane End Longton, c. 1810–12

- 43 JUG: probably Staffordshire or Liverpool, c. 1810–20

- 44 DISH: Leeds Pottery, Yorkshire, C. 1815-20

- 45 ‘PERSWAITION’: probably john Walton, Burslem, c. 1815–25

- 46 VASE AND COVER WITH PAGODA FINIAL Charles James Mason & Co., Fenton Stone Works, Lane Delph, Fenton, c. 1826–45

- 47 FLASK IN THE SHAPE OF A GIRL HOLDING A DOVE: James Bourne & Co., Denby or Codnor Park, c. 1835–40

- 48 THE ‘BULRUSH’ WATER JUG: Ridgway & Abington, Hanley, c. 1848–60

- 49 POT-LID: T.J. & J. Mayer, Dale Hall Pottery Longport, Burslem, 1851

- 50 EWER AND BASIN: Minton, Stoke-on-Trent, 1856

- 51 THE PRINCESS ROYAL AND PRINCE FREDERICK WILLIAM OF PRUSSIA: Staffordshire, 1857

- 52 JUG: John Phillips Hoyle, Bideford, North Devon, 1857

- 53 GIANT TEAPOT: probably Church Gresley or Woodville, Derbyshire, 1882

- 54 FLAGON: Doulton & Co., Lambeth; decorated by George Tinworth, 1874

- 55 TILE PICTURE: William De Morgan & Co., Sands End Pottery, Fulham, c. 1888–97

- 56 OWL: Martin Brothers, Southall, modelled by Robert Wallace Martin, September, 1903

- 57 HOP JUG: Belle Vue Pottery, Rye, Sussex, 1899

- 58 VASE: designed by William Moorcroft for James Macintyre & Co., Washington Works, Burslem, and made there or at Cobridge c. 1911–13

- 59 DISH: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Etruria; decorated by Alfred Powell, c. 1908

- 60 JUG: Royal Doulton, Burslem, c. 1930–40

- 61 DINNER PLATE: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Barlaston, 1955

- 62 PAGODA-LIDDED BOWL: Bernard Leach, StIves, Cornwall, c. 1960–5

- 63 VASE: Hans Coper, c. 1966–70

- 64 DEEP-SIDED BOWL ON A HIGH FOOT: Alan Caiger-Smith, Aldermaston Pottery, 1981

13 - BOTTLE: John Dwight, Fulham, c. 1689–94

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 September 2010

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Glossary

- 1 JUG: Scarborough, Yorkshire, c. 1250–1300

- 2 DRINKING POT: probably English, c. 1545–60

- 3 FLAGON: probably Derbyshire or Staffordshire, c. 1630–60

- 4 BOTTLE: Christian Wilhelm, Southwark, 1628

- 5 DISH: Southwark, 1651

- 6 JUG: probably Harlow, Essex, c. 1630–60

- 7 TWO-HANDLED TYG: probably Henry Ifield, Wrotham, Kent, 1668

- 8 TULIP CHARGER: London, 1661

- 9 ‘NOBODY’: London, 1675

- 10 DISH: Thomas Toft, Staffordshire, c. 1662–85

- 11 POSSET POT AND SALVER: London or Bristol, 1685 and 1686

- 12 CISTERN: London, perhaps Norfolk House, Lambeth, c. 1680–1700

- 13 BOTTLE: John Dwight, Fulham, c. 1689–94

- 14 MUG: David and John Phillip Elers, probably Bradwell Wood, Staffordshire, c. 1691–8

- 15 JUG: Staffordshire c. 1680–1710

- 16 COVERED CUP WITH FOUR HANDLES AND A WHISTLE: probably South Wiltshire, 1718

- 17 DISH: Samuel Malkin, Burslem, c. 1720–30

- 18 SIX CHINOISERIE TILES: Bristol or London, c. 1720–50

- 19 PUNCH BOWL AND COVER: Liverpool, 1724

- 20 HUNTING MUG: probably Vauxhall Pottery, 1730

- 21 TWO-HANDLED LOVING CUP: probably Nottingham or Crich, 1739

- 22 MILK JUG AND TEAPOT: Staffordshire, c. 1725–45 and c. 1740–50

- 23 PEW GROUP: Staffordshire, c. 1740–50

- 24 BEAR JUG OR JAR: Staffordshire, c. 1740–70

- 25 CAMEL AND MONKEY OR SQUIRREL TEAPOTS: Staffordshire, c. 1750–5

- 26 JUG: Staffordshire, c. 1755–65

- 27 DISH: Liverpool, c. 1755–60

- 28 TEABOWL, SAUCER AND COFFEE POT: Staffordshire, c. 1750–65

- 29 COFFEE POT: Staffordshire, 1760

- 30 TEAPOT: probably Josiah Wedgwood, Burslem, c. 1759–66

- 31 TUREEN: Staffordshire, c. 1760–5

- 32 TEAPOT: Josiah Wedgwood, Etruria, printed in Liverpool by Guy Green, c. 1775–80

- 33 JUG: Yorkshire, 1780

- 34 CENTREPIECE: probably Leeds Pottery, Yorkshire, c. 1780–1800

- 35 STGEORGE AND THE DRAGON: Staffordshire, c. 1780–1800

- 36 TOBY JUG: c. 1790–1810

- 37 DEMOSTHENES: Enoch Wood, Burslem, c. 1790–1810

- 38 ERASMUS DARWINS PORTLAND VASE COPY: Josiah Wedgwood, Etruria, Staffordshire, c. 1789–90

- 39 TEAPOT: probably Sowter & Co., Mexborough, Yorkshire, c. 1800–11

- 40 OBELISK: Bristol Pottery, Temple Back, Bristol, 1802

- 41 DINNER PLATE: Spode, Stoke-on-Trent, c. 1806–33

- 42 GARNITURE OF FIVE COVERED VASES: Richard Woolley, Lane End Longton, c. 1810–12

- 43 JUG: probably Staffordshire or Liverpool, c. 1810–20

- 44 DISH: Leeds Pottery, Yorkshire, C. 1815-20

- 45 ‘PERSWAITION’: probably john Walton, Burslem, c. 1815–25

- 46 VASE AND COVER WITH PAGODA FINIAL Charles James Mason & Co., Fenton Stone Works, Lane Delph, Fenton, c. 1826–45

- 47 FLASK IN THE SHAPE OF A GIRL HOLDING A DOVE: James Bourne & Co., Denby or Codnor Park, c. 1835–40

- 48 THE ‘BULRUSH’ WATER JUG: Ridgway & Abington, Hanley, c. 1848–60

- 49 POT-LID: T.J. & J. Mayer, Dale Hall Pottery Longport, Burslem, 1851

- 50 EWER AND BASIN: Minton, Stoke-on-Trent, 1856

- 51 THE PRINCESS ROYAL AND PRINCE FREDERICK WILLIAM OF PRUSSIA: Staffordshire, 1857

- 52 JUG: John Phillips Hoyle, Bideford, North Devon, 1857

- 53 GIANT TEAPOT: probably Church Gresley or Woodville, Derbyshire, 1882

- 54 FLAGON: Doulton & Co., Lambeth; decorated by George Tinworth, 1874

- 55 TILE PICTURE: William De Morgan & Co., Sands End Pottery, Fulham, c. 1888–97

- 56 OWL: Martin Brothers, Southall, modelled by Robert Wallace Martin, September, 1903

- 57 HOP JUG: Belle Vue Pottery, Rye, Sussex, 1899

- 58 VASE: designed by William Moorcroft for James Macintyre & Co., Washington Works, Burslem, and made there or at Cobridge c. 1911–13

- 59 DISH: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Etruria; decorated by Alfred Powell, c. 1908

- 60 JUG: Royal Doulton, Burslem, c. 1930–40

- 61 DINNER PLATE: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Barlaston, 1955

- 62 PAGODA-LIDDED BOWL: Bernard Leach, StIves, Cornwall, c. 1960–5

- 63 VASE: Hans Coper, c. 1966–70

- 64 DEEP-SIDED BOWL ON A HIGH FOOT: Alan Caiger-Smith, Aldermaston Pottery, 1981

Summary

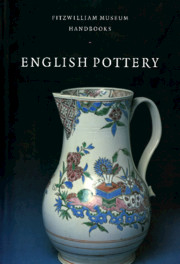

Salt-glazed stoneware with marbled bands, thrown, turned and decorated with applied reliefs: overlapping busts of William III and Mary II, a flying bird, two Merry Andrews (clowns), a winged cherub's head, a crane and a medallion with initial C amongst foliage. Height 17 cm. C.1194–1928.

Glass bottles made in England before about 1650 were not very strong and during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries hundreds of thousands of sturdy salt-glazed stoneware bottles were imported from the Rhineland to serve as containers for wine and other liquids, such as perfumed waters. Several attempts were made to produce them here, for example, at Woolwich about 1660, but these ventures were short lived. The first person to master the technique of salt-glazing and to continue successfully for a long period was John Dwight (c. 1633/6–1703). During the late 1660s Dwight, a lawyer by profession, was Registrar of the diocese of Chester and conducted experiments to produce stoneware at Wigan. In 1671/2 he moved to Fulham and in April 1672 was granted a patent for making ‘China and Persian ware’ and also ‘the Stone Ware vulgarly called Collogne Ware’. In 1684 a renewal of the patent included various other types, among them ‘marbled Porcellane Vessels’ but there is no evidence that the experimental porcelain made by Dwight in the 1670s was produced commercially.

The ‘sprigs’ on this bottle were made with brass stamps, some of which were found at the Fulham pottery in the 1860s and were later acquired by British Museum. The initials AR on one of them probably stand for the medallist Reinier or Regnier Arondeux (c. 1655–1727).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- English Pottery , pp. 36 - 37Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1995