In December 1917, delegations from Russia, Ukraine, Austria-Hungary, Prussia, Bavaria, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire travelled to Brest-Litovsk in the prospect of peace. In this ruined market town, only the train station and the nineteenth-century citadel were still standing. Before the war, Brest used to link the inland colonies of the Russian Empire with its commercial veins. Now under German control, it served as a market for a different kind of commodity: political prestige.

On the table were not only issues of territorial integrity but the question of legitimate succession to Europe’s vanishing empires.Footnote 1 The Russian Empire’s losses in the war precipitated a revolution in Petrograd in February 1917, which enabled the Bolsheviks, a party formed in exile, to assume control over the state in a coup in October of that year. They saw themselves as the vanguard of a new humanity, which had come to replace Europe’s bankrupt imperial elites. After the tsar’s abdication and the failures of the Provisional Government, they handled the Russian Empire’s defeat and initiated the peace talks.Footnote 2 Two years after the event, journalists such as the American John Reed presented the Bolshevik rise to power as an inevitable revolution with global potential.Footnote 3

Nikolai Lenin, a pseudonym he derived from the river of his Siberian exile, considered the collapse of imperial governments in the war to be the final culmination of global capitalism. He noted that previous theoretical models of imperial crises, which he had studied in libraries in London, Bern, and Zurich, failed to predict the impact of wars between empires on the ability of revolutionary groups to gain control over states. Now that even the former Russian Empire with its tiny working class had Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils, a revolution seemed more likely in the rest of Europe as well.Footnote 4

However, this is not in fact what happened in most of central Europe in the decades between 1917 and 1939. Even if we compare the changes during this time with more critical, non-Bolshevik perspectives on the Russian case, central Europe experienced a less radical transformation in this interval. The societies west of the new Russian border did not change their social, institutional, and economic basis to the same degree. Some of the more radical changes, such as giving women the vote, which immediately increased the number of active citizens in Europe, were not the work of new republican governments. Thus in Britain, a surviving empire and a monarchy, national citizenship and women’s suffrage also replaced imperial forms of subjecthood after the First World War.Footnote 5

This remained so until the new divisions of Germany and eastern Europe, which took place in the aftermath of the Hitler–Stalin pact of 1939 and the Yalta Conference of 1945. Before this time, seemingly radical changes like the abolition of monarchies in twenty-two German princely states and in Austria were the effects of mostly liberal constitutional reforms. Acts of retribution against the old elites were also more moderate in central Europe than in Russia. Most members of the Habsburgs, Hohenzollerns, and other families survived in exile. There were no twentieth-century Marie Antoinettes west of the Curzon line, even though writers like the Austrian Stefan Zweig did invoke her name in a bestselling biography.Footnote 6 Revolutionary situations did happen between 1918 and 1922 in various cities, like Munich, Berlin, Kiel, Turin, and Budapest. But in many cases, radical movements associated with disbanded officer corps of the old imperial armies were more successful there than the contemporary socialist and anarchist movements or the relatively local sailors’ mutinies. Moreover, new leaders on the left and the right, including Mussolini in Rome, Friedrich Ebert in Weimar, Adolf Hitler in Potsdam, and Franco in Spain all sought public accreditation from the representatives of Europe’s traditional elites.Footnote 7

By 1924, the most charismatic of the revolutionary leaders on the left, people like Kurt Eisner in Munich, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg in Berlin, and Giacomo Matteotti in Rome, became victims of political assassination alongside liberal reformers such as Walther Rathenau; others, such as Antonio Gramsci, Béla Kun, and György Lukács, were imprisoned or went into exile. Among historians, there were only two brief moments when the events in Germany were discussed under the label of ‘revolutions’. The first was when the Russian socialists such as Larisa Reisner and Karl Radek hoped to encourage a revolution there in the early 1920s.Footnote 8 The second time was in the aftermath of 1968, when historians who were disenchanted with the actions of the Soviet Union in their own lifetime sought to recover an alternative history of European socialism.Footnote 9

This book argues that intellectual communities and transnational cultural networks played a key role in establishing a consensus against revolution in central Europe. Looking chiefly at the decades between the revolution in Russia in 1917 and the beginning of Europe’s post-war integration in 1957, I suggest that during this period, the old elites of continental Europe managed to convert their imperial prestige into new forms of power. The limited degree to which the Bolshevik revolution was able to spread west, this book argues, had much to do with the existence of media in which some vocal members of the European intelligentsia could discuss their own implicated role in the process of imperial decline, and even share a certain degree of enthusiasm for the revolutions.

The post-imperial transition in central Europe between 1917 and the 1930s was closer in character to British imperial reforms between the abolition of slavery of 1833 and the Representation of the People Act of 1918 than to the revolutions in Russia.Footnote 10 Why did revolutions not gain more public support west of Russia? There cannot be any one answer to this question, but this book contributes something to this larger question by highlighting the factor of social prestige in the transformation of power. Recovering the transnational sociability and intellectual production of a group of, mostly liberal, German-speaking authors, it reveals the persistent authority of people who belonged to the former elites of multiple continental empires.Footnote 11 They considered themselves implicated in Europe’s imperial past, even though, as one of them put it, they were ‘historically speaking, dead’.Footnote 12

Memoirs and autobiographic reflections were one domain in which their imperial memories circulated. But the German-speaking aristocratic intellectuals of interwar Europe also became political activists and theorists of internationalism in interwar European institutions such as The Hague Academy of International Law, newly founded academies of leadership like the Darmstadt School of Wisdom, or the League of Nations unions.Footnote 13 Joining voices with more radical contemporaries who criticized parliamentary democracies and bourgeois values from the Left and the Right, they formed a peculiar international from above, which had the power to give or deny recognition in Europe’s informal circles of elite sociability. In this way, the old Germanic elites fulfilled a double function. In Germany, they helped to overcome Germany’s intellectual isolation by mobilizing their international connections. Internationally, they embodied the ‘old’ world of Europe’s continental empires. They also became self-proclaimed representatives of Europe in encounters with the new intellectuals of the non-Western world, including global stars such as the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore.

The position of German intellectuals changed dramatically between the two peace treaties that ended the First World War. At Brest-Litovsk, Germany and Austria-Hungary were winning and dictating the terms. By contrast, the Peace of Versailles not only prominently marked Germany’s defeat as a nation. It also identified the old German-speaking elites as the representatives of more than one dismantled empire. As this book will show, however, paradoxically, this gave Germanic intellectuals greater international reach. As figures of precarious status, they provided the post-imperial societies of Europe with a personal vision of transition that they otherwise lacked.Footnote 14

As members of a transnational elite, they actively resisted thinking about their present in terms of ‘old’ and ‘new’ regimes, which many contemporary political movements tried to establish. Such attitudes to revolutions have been previously expressed in British political thought in response to the French Revolution and the anti-Napoleonic struggles.Footnote 15 In the new international situation emerging around the League of Nations and other international bodies, the association of the German elites with multiple vanished empires, offered a unique form of cultural capital.

Looking back at the decade which followed Brest-Litovsk, Baron Taube, a former Russian senator remarked: ‘We are truly living in strange times. Former ministers, field marshals who had been dismissed and monarchs without a throne’ are putting the work they had been trained to do to rest in order to put to paper in haste the things which they had lived and seen ‘in happier days, when they were still in power’.Footnote 16 But even as memoirists, these ‘subjective witnesses of the first rank’, Baron Taube argued, could not be trusted because in remembering, they wanted to expiate themselves. By contrast, he thought that his own memory of the events he dubbed the ‘Great Catastrophe’ had more public value, if only because many senior diplomats representing their empires at Brest-Litovsk were also soon removed from the political stage.Footnote 17 People like Taube were not just observers in the ‘second row of the ministerial lodge of the Russian empire’. He belonged to a rank of past historical actors, who were also leading internationalists of their generation.

To reconstruct how the intellectual communities of Europe remained connected through shared imperial mentalities, I look at authors who were social celebrities or well known in these circles. Some of the most visible personalities in these circles of post-imperial sociability were authors and intellectuals of aristocratic background, often with connections in imperial civil service or international law. These included the diarist Count Harry Kessler, a committed internationalist who was a Prussian officer with Anglo-Irish roots; Count Hermann Keyserling, a Baltic Baron who became a philosopher of global travel and identity, and Baron Hans-Hasso von Veltheim, a German Orientalist with a cosmopolitan social circle. The Austrian prince Karl Anton Rohan, a lobbyist and founder of the organization that preceded UNESCO, was a more important personality connecting old Europe with intellectuals, bankers, and industrialists of the post-war era, as well as building some ties to the nascent fascist movement in Italy. Count Coudenhove-Kalergi, the activist of Pan-European unity, was equally well known in central Europe, Britain, and the United States. Baron Mikhail von Taube was an international lawyer from the Russian Empire teaching in Sweden, Germany, and the Netherlands. As individuals and members of a wider network of intellectual communities, these authors and others of similar background contributed to the growth of an internationalist mentality by sharing experiences of the First World War, as well as successive crises of European democracies and economies. Their family networks past and present gave them a personal connection to multiple processes of revolution and reform which took place almost simultaneously in Ireland, Russia, Germany, and Austria-Hungary. They were, to adopt Donald Winnicott’s term, ‘transitional’ subjects for post-imperial societies.Footnote 18 Their family histories, connecting them to the history of more than one empire, helped others make sense of the transition from imperial to post-imperial Europe.

Power, prestige, and the limits of imperial decline

Readers of international news were unlikely to have heard of Brest-Litovsk before the peace treaty. In 1915, the English-speaking educated public was interested in the region mostly because it was home to the bison, Europe’s biggest animal, whose extinction was imminent because of the protracted war. ‘But for the jealous protection of the Tsar it would, even here, long since have vanished’, lamented the Illustrated London News, if it weren’t for the ‘zoos or private parks such as those of the Duke of Bedford, and of Count Potocky, in Volhynia’.Footnote 19 Few could foresee then that in 1918, Europe’s last tsar and his family would vanish even before the last bisons.

But to more astute analysts of modern empires such as John Hobson, the war merely highlighted what he had already observed nearly two decades earlier: empires persisted despite the fact that the majority of their populations lacked a common interest in imperialism.Footnote 20 Instead, as complex systems of social and economic relations, empires brought benefits to particular, increasingly global, commercial, and financial enterprises, which included the old dynasties as the oldest holders of capital in their empires. These national and transnational minorities were the chief beneficiaries of empires, and as such Hobson’s readers such as Lenin concentrated their critique on them.

Other theorists of empire agreed with much of this analysis but were more sceptical in their conclusions. They believed that cultural values such as prestige were just as significant in maintaining stability in empires, which meant that even the supposed enlightenment of imperial subjects about their true interests would not necessarily lead to revolution. What I want to underline is that intellectuals and civil servants working for empires were among those minorities who benefited from empires by enjoying the existence of special honours, cultural goods, and the benefits of a multicultural identity.

In this book, I look at one of the subgroups of these intellectual elites who could be described as a kind of European imperial intelligentsia. Like the Russian origin of this term suggests, this group comprised critics of imperial governments who were simultaneously profoundly implicated in their imperial economic and cultural systems of prestige. They questioned the way ideas of the nation, of culture and civilization, were used to justify imperial rule, and yet they also questioned the way these were used by the revolutionaries.Footnote 21 In this capacity, they can serve as guides to a social and intellectual history of continental European imperialism that could build on the work of scholars of the British Empire and, more recently, expanded in the form of the history of international political thought.Footnote 22 In addition, their perspective on empire opens up new possibilities for a more modest form of global and transnational history of imperialism after the age of empire.Footnote 23 The theorists and witnesses of the twentieth-century revolutions engaged with modernist forms of narrative and contemporary traditions in philosophy to make sense of their particular condition. They lived in an age in which empires declined, yet imperialism persisted. Moreover, their ideas of empire had formed in a trans-imperial context, reflecting the character of elite sociability in the Belle Epoque as well as the cultural traditions of European education.Footnote 24 Yet their peculiar endorsement of imperialism without empires was frequently constructed in highly traditional forms of writing, which hearkened back to the idea of a united Europe. Their golden age was anchored in the ‘non-radical’ moments of the enlightenment, in the cosmopolitan nationalism of liberals such as Mazzini, in technocratic idealism of the Saint Simonians and Cobden, and the aesthetic reform movements of William Morris and the Theosophical Society.Footnote 25 The political thought of the twentieth-century internationalist configuration that is at the centre of my attention in this book takes the form of autobiographies, diaries, memoirs, and classical dramatic fiction, along with treatises and other works of theory.

As one French publisher put it in 1920: ‘Que nous réserve le vingtième siècle? L’Europe pourra-t-elle maintenir son hégémonie exclusive sur le monde?’ [‘What does the twentieth century hold in stock for us? Will Europe be able to maintain her exclusive hegemony over the world?’] In times of ‘dismemberment of the Russian, Austro-Hungarian and other empires’, these questions worried even those who had been critical of previous imperial excesses.Footnote 26 In fact, things had been falling apart in Europe’s other empires, too.Footnote 27 Calls for national self-determination and home rule reached as far as the telegraph cables and the imperial liners, from the Atlantic to the Indian Oceans, across the Mediterranean, the Irish, and the Baltic Seas.Footnote 28 Increasingly, imperial governments were perceived as holders of an oppressive, alien type of rule that went against the interests of the majority of their subjects – metropolitan, peripheral, and colonial.Footnote 29 For a short while, the Ottoman and German empires and Austria-Hungary survived; but by 1922, these powers also unravelled. In the period between 1916 and 1922, new national republics like Germany, Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the three Baltic states, emerged, alongside new federations like the Kingdom of Yugoslavia or the League of Nations. Particularly in the lands formerly belonging to the defeated empires of continental Europe, the old landowning, military, and political elites seemed discredited.

In Russia, dismantling the old elites went further than anywhere else in Europe. The Bolshevik party began its rise to power by calling into question the very basic hierarchies of rank inside the imperial army. A ‘Decree on the destruction of estates and civil honours’ followed, which proclaimed the abolition of all status of privilege alongside deprived statuses like that of a peasant. What remained were the ‘free peoples of Russia’.Footnote 30 The Romanoffs, whose Russian-sounding name obscured their relation to the German houses of Schleswig and of Hessen-Darmstadt, had already been exposed as ‘inner Germans’ and enemies of their former subjects under the Kerenski administration. Under the Bolsheviks, they were executed without trial along with their valet, their cook, and their butler, away from the public eye, in the heart of the Urals, where many Russian socialists and anarchists had been spending their prison sentences since the 1880s.Footnote 31 Some among the Bolsheviks thought that such actions were necessary in order to achieve the kind of self-determination they were seeking for the former imperial subjects. Former inner peripheries like the ‘Pale of Settlement’, a large rural ghetto created by Catherine II of Russia, to which the Jews of Russia had been confined, were decolonized.Footnote 32 Their demand for self-determination also extended to the subject peoples of other empires, such as the Armenians, as well as the Baltic territories now claimed by the German Empire.Footnote 33 But to say that in tearing down the old regimes, the Bolsheviks became universal spokesmen for the world’s subalterns would be misleading.Footnote 34 They were dismissive of the Ukrainian constitutional democrats, for instance, who were their closest rivals in imperial succession. Internally, they also unleashed a brutal civil war, now known as the Red Terror.Footnote 35 The ‘Lenin’ moment supported those post-imperial emancipation movements that helped secure the power of the party.Footnote 36

Elsewhere in Europe, the most visible representatives of the old elites, that is, Europe’s ruling dynasties, the officers of the imperial armies and other civil and diplomatic servants, also had to go. Most of the aristocratic families of Europe were of German background, but more recently, had closer ties to Britain. Their genealogies dated back to the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, dissolved by Napoleon in 1806. Three of the monarchs whose empires were involved in the First World War called Queen Victoria ‘grandma’, and English was spoken at home not only in the households of the British royal family but also in that of the Romanoffs and among the Baltic nobility. A popular desire to discredit these elites was the most visible effect of the war on post-war Europe. In Germany and Austria, members of the Hohenzollerns, the Wittelsbachs, and the Habsburgs, went into exile in 1918. In Austria, the Habsburgs were not only forced to abdicate but became a kind of familia non grata. In Britain, the ruling Saxe-Coburg Gothas had changed their name to Windsor, which was more rooted in national geography.Footnote 37 But even at a lower level of power, aristocratic families in the Baltic states and in Czechoslovakia were stigmatized and partially expropriated. For instance, family crests of the Baltic Barons were removed from Tallinn’s cathedral in Estonia, and larger forests were nationalized in Czechoslovakia.Footnote 38 In continental Europe, the officer corps of the old imperial armies, a classic context in which the habits of the old elite were formed, were disbanded.Footnote 39

However, at the slightly less visible lower level of their elite administration, the transformation of post-imperial central Europe was far less dramatic. Moreover, the Peace of Versailles shifted attention away from social revolutions and towards the intention to shame the German nation.Footnote 40 At Versailles, the German negotiators tried to develop a model, which the Bolsheviks had pursued in Brest-Litovsk: to dismantle their ruling dynasty and key military elites for the sake of saving the nation from the burden of defeat.Footnote 41 But the representatives of the surviving empires, Britain and France, decided to make the German nation and not the elites of the old German Empire appear as the only surviving defeated power, so that it had to pay compensation for losses and damages, focusing on recorded atrocities such as the ruthless invasion of Belgium.Footnote 42 The cost was exposing Germany as the chief culprit behind the war, which emerged as a common purpose in which the interests Bolsheviks, who were not invited to Versailles, were aligned with those of Britain, France, and the United States.Footnote 43

Politics as conversion: the German elites after Versailles

By contrast to the unknown city of Brest, Versailles suffered from an excess of symbolic significance. It was the place where the new German Empire had been proclaimed after France’s defeat by Prussia in 1871. That location had in turn been chosen because of Versailles’ historical place in French history, as the main residence of the court of the former French monarch, who had been deposed and later executed with his family in the course of the French revolution of 1789–93. In 1919, it seemed appropriate for the purposes of French and British interests to turn Versailles into the place where the German nation, and not the German dynasties, was discredited as the chief culprit behind the war. The result was that in most of continental Europe, the empires saved face and avoided any radical redistribution of power, opting instead for a joint redistribution of Germany’s colonial possessions, along with those of Austria-Hungary and the Ottomans. The surviving empires of France and Britain, and the moderate successor regimes of imperial Germany and Austria, then embarked on a more controlled post-imperial devolution in the rest of Europe. In Germany, this involved even socialists like Gustav Noske in the violent crushing of emerging riots and uprisings.

As a result, even though new, socialist governments did come to power in Germany and in Austria-Hungary, the public dismantling of the old elites did not proceed as ruthlessly as in Bolshevik Russia after Brest-Litovsk. Instead, the former emperor, Wilhelm II, former officers of the disbanded armies, and former diplomats managed to preserve and even augment their prestige as holders of true national dignity which had been betrayed by the rest of Europe. An influential strand of national German history focuses on the way these dismantled elites paved the way to power for Hitler and the Nazis.Footnote 44 But as I want to show, in transnational perspective, some of these old elites also had other effects on European society and political thought, including strengthening a moderate consensus around liberal, moderately socialist, and internationalist values.

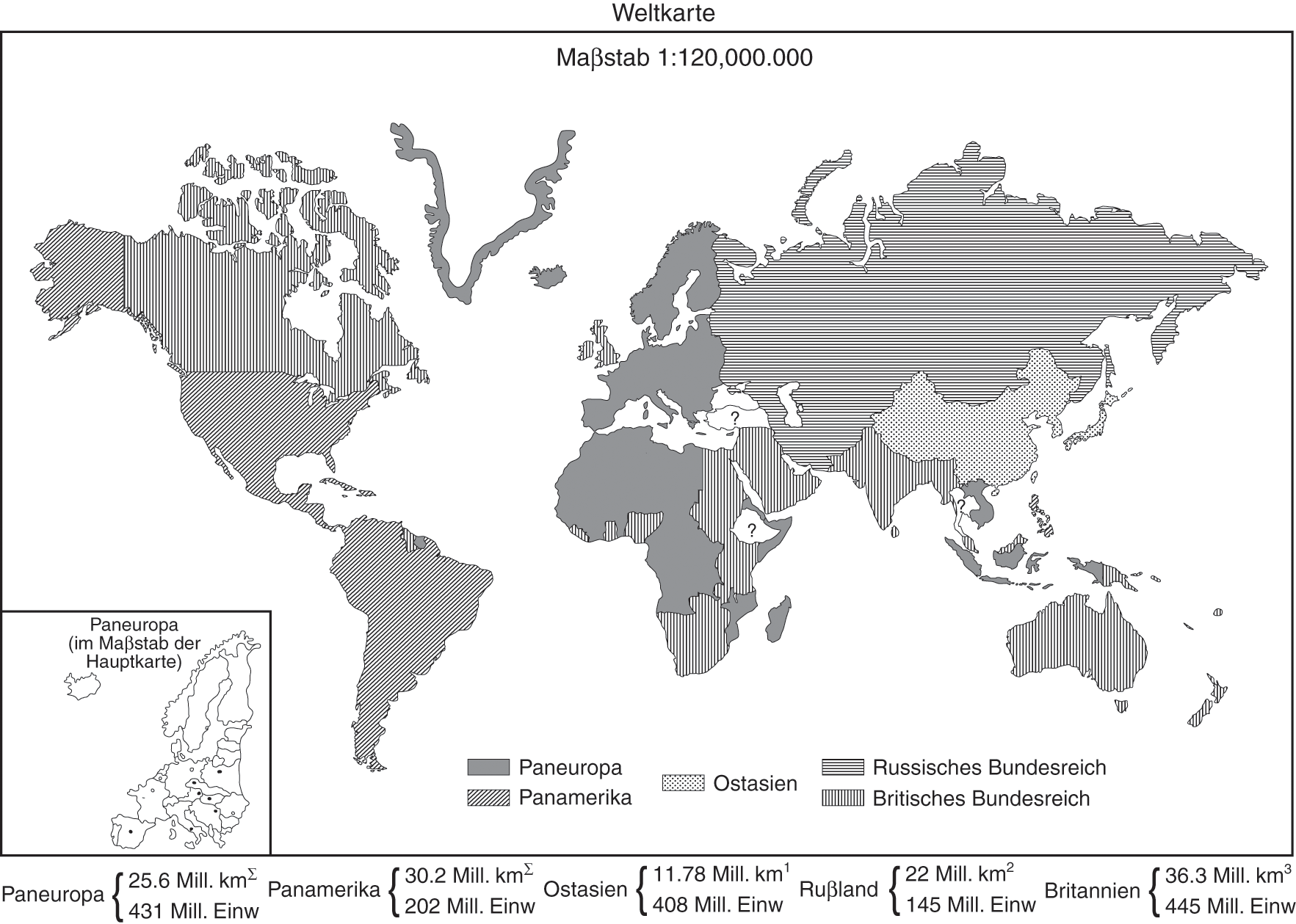

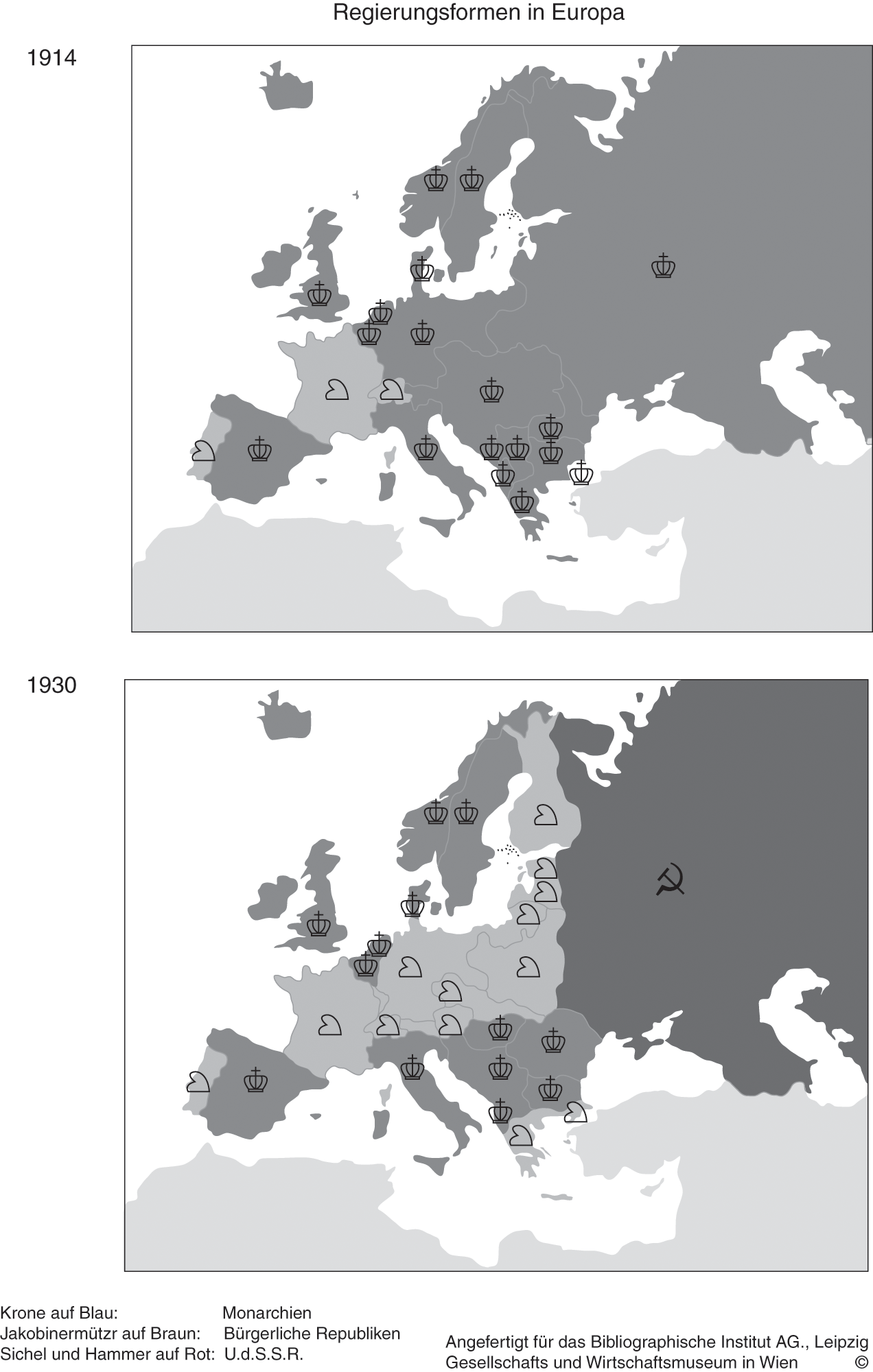

A set of two maps produced by Otto Neurath, an Austrian socialist, who briefly served as an economic advisor to the Soviet Republic of Munich, highlights the nature of the changes.

In the first map showing the year 1914, most European states, except France, Switzerland, and Portugal, are governed by monarchs. In the second map, in 1930, the landscape changed dramatically: the former exceptions became the rule. Now, Germany, a part of Finland, the Baltic states, Czechoslovakia, Ukraine, and Greece are marked with a Phrygian hat, a symbol of the Jacobin idea of national self-determination hearkening back to the French Revolution of 1789. The new exception is no longer west of the Rhine but east of the Bug: here, a hammer and sickle marked the peculiar union of workers and peasants, which distinguished it from the so-called ‘bourgeois’ national republics in central and western Europe.

But you can also imagine a third map in this sequence, in which the societies living under new ‘Jacobin’ hats nonetheless retain certain bonds which they had shared as subjects of monarchs and empires. In this book, I seek to draw attention to the role of a particular, mostly intellectual, network in fostering such bonds and crossing the boundaries between these new ‘Jacobin’ states.

It seems surprising at first that intellectuals of German origin would obtain such transnational visibility after the First World War, after Germany’s humiliating defeat. One of the reasons, I would argue, is that some of the most passionate and prestigious defenders of imperial great games had themselves turned into cautious advocates of change. By making their conversion to a new political situation public without necessarily endorsing revolutions, they facilitated such moderate forms of conversion for others. In using the term ‘moderate’, I do not wish to make a normative judgement of this community; it is merely a term I use to describe the form in which they intended to transform empires into their successor states, in distinction from Bolshevik Russia.

In his famous lecture in Munich in 1919, Max Weber, recently arrived from Vienna, addressed a group of students on the subject of choosing politics as their vocation.Footnote 45 Germany was discredited, and with it, his entire career, which he had devoted to building a Great German Nation. He had voiced this vision in his inaugural lecture on Political Economy in 1895. During the war, Weber moved away from the national liberal towards a more conservative and even colonialist position. Controversially, he joined the chauvinistic Pan-German League during the war to declare his commitment to German interests in world politics. Like many Europeans, and especially Germans, after the First World War, he reconsidered the foundations for his beliefs. He was no longer a theorist of a national political economy but, in a sense, an imperial thinker without an empire.Footnote 46 He even lectured on socialism to officers of the former Austrian imperial army. The entire intellectual community of which he formed a part devoted its attention to rethinking the consequences of imperial decline particularly for the cultural and political elites. This made eminent sense in a society without leadership, in a volatile, revolutionary Munich, where some of Weber’s closest friends were socialists and in prison.

Figure 1 Map after Otto von Neurath, Gesellschaft und Wirtschaft (Leipzig: Bibliografisches Institut, 1931)

Alongside Joseph Schumpeter’s comparative work on empires, Weber’s Politics as a Vocation provided a theory of reconstructing government and reinventing legitimacy in the absence of power. In the long evolution of European thought about the state, this text provides a conclusive arc to the story of transformation by which the early modern mirrors for princes facilitate the emergence of the modern state. As empires had collapsed, the imperium of the state risked following suit. Weber’s historical reconstruction of the Italian city states provided a recipe for mantenere lo stato.Footnote 47 This marked the moment which Quentin Skinner, speaking about Britain in the late 1950s, once described as ‘that final gasp of empire’.Footnote 48

Weber’s solution was to forge a new elite from history, to give society a kind of collective biography according to which it would not depend on the continuity of states and empires.Footnote 49 Weber, after 1918, was ‘fabricating ideals on earth’, to use Nietzsche’s phrase, and did so by means of creative genealogy.Footnote 50 He was creating a new moral code by rewriting a genealogy of political morality. Weber’s sources for comparative studies of empires were themselves imperial, but with an interest in perspectives from the periphery of empires: he compared the Prussian periphery of Ostelbia with Ireland, Bengal, and Poland, and looked at the transformation of aristocratic elites in all these different societies in comparison.Footnote 51 Seen in global perspective, the nobility was to him not only a reactionary class, as he had previously thought, but a ‘politically recyclable social stratum’ in the present.Footnote 52 The criteria he drew upon creatively combined traditional aspects of aristocratic habitus and the mentality associated with a Protestant ethic of work and commitment: the need for a certain code of honour, known as ‘noblesse oblige’, that would be independent from the prevailing ideologies of the day;Footnote 53 the preference of a life for politics over a life off politics; a special form of rule as ‘territorial power’ maintained through the division of spheres of right; and the feeling of noble detachment or contenance, which Nietzsche had praised as the ‘pathos of distance’, typical for aristocratic character.Footnote 54 He criticized the attempt some journalists made to place themselves seemingly above and outside societies, like ‘pariahs’. Instead, Weber argued, engaged journalists should become more like Brahmins.Footnote 55 His ‘analytical world history’ was thus deeply implicated in post-war German politics.Footnote 56 By speaking of revolutions often in the plural, and distancing himself from them through inverted commas, he sought to ridicule the attempt at revolution which at this time was being undertaken by Kurt Eisner and his followers.Footnote 57 He was also involved in it as the member of a delegation of German professors sent to Versailles to negotiate the consequences of German war crimes for notions of guilt and debt, and he co-founded the German Democratic party, a pro-republican liberal party which was only successful in the first years of the Weimar state.

The ideal type of a charismatic leader which Weber and his circle conjured up was to be a nobleman-cum-politician, a Brahmin-cum-pariah.Footnote 58 But Weber was adamant that in doing so he wanted neither to refurbish the old nobility nor to extend aristocratic status to the ‘industrial barons’ and bankers who became rich in the war. Instead, he demanded to ennoble the Europeans culturally through a theory of ‘charismatic education’.Footnote 59 Charisma is not only rational but constituted by emotional regimes. It also partly overshadows its own subjects.Footnote 60 It can be depersonalized through blood ties but also by property relations such as primogeniture. Charismatic personalities through inspiration and empathy can change established social norms.Footnote 61 Similarly to Weber, Schumpeter believed that the core ‘unit’ of conversion and adaptation was the family. He called for a ‘patrimonialization of elites’, that is, the appropriation of old Europe by its purported modernizers. The former elites of Europe’s empires continued to influence the nature of power, prestige, economic profits, as well as the cultural identity of post-imperial societies.

The history of aristocratic status in Europe served as a useful model for calibrating cultural identities in the age of conflicting national demands for self-determination. Already before the war, Georg Simmel had emphasized the ability of nobles to ‘get to know each other better on one evening than regular citizens in a month’, while remaining detached from the vernacular cultures of their nation. ‘In England the Fitzgeralds and the Dukes of Leicester are from Florence, the Dukes of Portland from Holland, in France the Broglie are from Piedmont, the Dukes des Cars from Perugia, the Lynar from Faenza, in Poland the Poniatowski are from Bologna, in Italy the Rocca are from Croatia, the Ruspoli from Scotland, the Torlonia from France, etc.’Footnote 62 In different historical moments, such as during the French Revolution, nobles therefore could form a sort of aristocratic international or ‘chain’, a negative safety network. Conjuring up this past helped some intellectuals to transcend Germany’s isolation after Versailles.

As Simmel himself was well aware, it was constitutive of aristocratic identity to form social networks and be part of familial associations that transcended national borders – aristocrats were ‘superior’ everywhere because everywhere they were thought of as being of different blood and cultural constitution than the majority of the population.Footnote 63 But this was before the war; like many others in his generation, during the war, Simmel now expected full commitment to the German cause in the same way in which the German princes in the age of Napoleon had formed an ‘aristocratic chain’ of German nobility seeking to defend their lands from the French invasion.Footnote 64

Max Weber was a central figure at wartime gatherings of intellectuals in Castle Lauenstein, where he spoke about the ‘Personality and the Orders of Life’ and about the ‘aristocracy of the mind’ as concepts which would convert old into new elites.Footnote 65 The aim of such gatherings was to rethink the future of Germany from a post-war perspective even as the war was still going on, and to provide a new sense of community among intellectuals who believed themselves to have been wronged by international anti-German propaganda. A medieval castle, which had been restored in the historicist fashion in the late nineteenth century, furnished the setting for esoteric mystery plays in which all delegates were invited; the Holy Roman Empire was, in a sense, in the air. One of the themes of the 1918 conference was ‘The Problem of Leaders [das Führerproblem] in the State And In Culture’. It was in these contexts that a new idea of aristocratic leadership was being developed, one that drew from examples of historical nobilities but disassociated the idea of aristocratic virtues from people with an aristocratic background.

Ideas about the future of elites in post-imperial Europe were also produced in Italy and in Switzerland during this time. Vilfredo Pareto, a proponent of moderate and liberal governments, saw the elite as a ‘class of people who have the highest indices in their field of activity’.Footnote 66 By this token, elites prevailed in old regimes and in revolutionary societies alike.Footnote 67 Some revolutions involved constitutional change without radical distribution of resources, in a kind of ‘revolving door’ model of elite circulation. In other post-imperial societies, the elites had changed in a more vertical and radical fashion. But in all of them, the idea of the ‘old elites’ that were to be discarded in favour of new political communities was central, and they regarded themselves as a part of that configuration.

In this sense, Pareto’s much-cited proclamation of ‘history as the graveyard of aristocracies’ and Robert Michels’s contemporaneous ‘iron law of oligarchy’ were not just analytic statements, but performative interventions in an uncertain economy of values. According to both, progress depended on the permeability of classes and parties, and it could become stale when one’s class position had become second skin, a type of cultural identity.Footnote 68

A sympathetic but cautious observer of revolutions, the socialist Antonio Gramsci concluded that a ‘new order’ had been born. Its longevity would depend on the way in which the relationship between power and persuasion would be reconfigured. While the events in Russia showed clearly how power could be transferred by means of violence, he believed that the success of the revolution ultimately depended on the ability of intellectuals to persuade populations of a new ethics and the principles of a new, post-imperial world order.Footnote 69 Part of this process was persuading the old elites that the old rules of empire no longer applied.

One element of elite conversion involved the problem of recognition between the old elites and their challengers. Looking back at this period, the author of the Austrian constitution of 1919, Hans Kelsen, remarked that in addition to the classical theory of international relations, which knows recognition only among established states and their representatives, ‘insurgents’ with effective powers of governments, now had to be taken into account.Footnote 70 The problem of recognition also concerned personal relationships among diplomats. Thus for instance, during the negotiations in Brest-Litovsk, the diplomats of the old empires lived in the immediate vicinity of each other for four months. But this close proximity made their heterogeneity apparent. In their conversations with the press and in memoirs which were soon published, for instance, they also tried to discredit each other in what could be called utterances of ‘derecognition’.Footnote 71 British observers of the negotiations judged the representatives of the old empires very differently from those of their successor states. They held the aristocratic elites of the former empires, their chief enemies, in high esteem; by contrast, they had only contempt for the leading members of the Russian delegation, and described the Ukrainian representatives as youthful ‘canaries’ whose only function was to be entertained by the grown cats.

The Bolsheviks, on the contrary, not only discredited the old governments but also absorbed the ideas of their old critics. Thus in abolishing religion and private property, and in promoting national self-determination, the Bolsheviks assumed – and thus, declared – the existence of liberal values such as religious toleration that no previous Russian government had actually announced.

The process of calibrating levels of recognition among old and new elites took place in uncharted legal territory. Normally, only established states that mutually recognized each other could enter into negotiations with their respective representatives. Here, not all parties, which had effective control over territories, were actually representing internationally recognized states.

Post-imperial phantom pain and its writers

In the aftermath of the revolution in Russia and the shaming of Germany at Versailles, many representatives of the German-speaking elites considered themselves to be connected to the political and cultural economy of more than one empire with their educational and professional background. After imperial decline, the choices they faced ranged from adaptation to the new national discourses of the post-imperial successor states, to nostalgia for past empires, or advocacy for a new kind of internationalism.

By the mid-1920s, aristocratic intellectuals of Germanic origin became recognizable as a new type of international celebrity. Their pre-eminence was rooted in the empires of Germany, Russia, and Austria-Hungary. They were considered odd but they were still sought after as public speakers. One of the most distinctive voices was the Habsburg count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi. According to theorists of revolution, people like him should have been relegated to the dustbin of history, like the empire he had come from. Yet instead, Coudenhove became something of an international celebrity in mid-twentieth-century Europe.Footnote 72 In 1923, he popularized the idea of a Pan-European Union, which became widely associated with him in subsequent years, not just in German-speaking communities but also in international circles. Coudenhove argued that the world had to cease thinking in nations and to begin thinking in continents before a world federation of states would eventually be possible in the utopian future. In doing so, Pan-Europe would have to struggle side by side with the Soviet Empire, the British Commonwealth, and with Pan-America. He imagined that Pan-Europe would include the French and formerly German colonies of Africa and Asia, along with French Guyane, as territories to be held in common by the European nations.

Coudenhove has often been presented as a singular presence in post-imperial Europe. There was indeed something slightly exotic about his appearance to most Europeans, since he had a Japanese mother, which was quite unusual at the time, particularly in the relatively closed world of the Austrian aristocracy. But more important than this circumstance of his personal biography was the fact that he belonged to a larger network of continental Europeans, a voice from Europe’s past whose judgement was sought by a surprising range of contemporaries. John Hobson, the old British critic of empire, wrote a sympathetic review of Coudenhove’s book for The Manchester Guardian, and Coudenhove had equal appeal among British conservatives, among Indian delegates to the League of Nations, and leading French socialists of his generation, like Aristide Briand.Footnote 73

He saw it as his calling to start thinking globally and draw lessons from the collapse of Europe’s empires on a universal scale. Against the backdrop of the discourse on self-determination, he made his own self the subject of his interventions, constructed less in terms of character and more in terms of its ties to the Byzantine and Holy Roman empires, as well as those of Russia and Austria-Hungary. His public persona seemed to give the new Europeans, which were not quite the Jacobins of the twentieth century, a sense of orientation.

Aristocratic intellectuals were, a recent historian of the Russian nobility-in-exile argued, the ‘Former People’ of Europe.Footnote 74 In fact, the category of ‘former people’ applies to the majority of twentieth-century Europeans. What distinguished the ‘aristocratic authors’ was their capacity to give this ‘former’ status a veneer of distinction.Footnote 75 The aristocratic intellectuals provided them with a biographical path through ideological contradictions and gave a personal face to elusive abstractions like ‘Europe’. As Chapter 1 shows, even aristocrats whose families were less well known than the Habsburgs obtained a special charisma of decline between the wars, which had a cultural value of its own. The German officer class was another visible group among the former imperial subjects who remained connected transnationally. Some intellectuals who were former officers became mediators of a cosmopolitan memory of war, as the second chapter discusses.

Intellectuals belonging to the former diplomatic, military, cultural, and political elites of the Russian and German empires became important mediators for cosmopolitan cultural communities, maintaining prestige by virtue of their detachment from nations, as Chapters 3–5 demonstrate.

The Austrian journalist Karl Kraus had first identified a new social type among this group which he called the ‘aristocratic writers’.Footnote 76 They were in a sense the opposite of Voltaire: not intellectuals ennobled by their writing but authors whose authority came from their nobility. The particular charisma of the intellectuals of old nobility came from the context of imperial decline and revolution in which they lived. This gave their personal reflections on family history and autobiographic perspectives on European history, which populated newspapers, journals, and memoirs in the interwar period, more appeal. Many among them were of German descent, which did not necessarily mean that they were German or Austrian subjects: a large number included former Russian subjects like the Baltic Barons, a group to which Taube belonged.

As authors, the aristocratic writers of German background exercised a particular form of dilettantism that had been typical of nobility for a long time, but appeared in a new light in post-war Europe.Footnote 77 In the aftermath of the First World War, this dilettantism not only obtained much wider appeal among readers but also a new philosophical justfication. Between the 1900s and the early 1920s, a strand of philosophy now known as ‘vitalism’, or the philosophy of life, an early form of existentialism, had become fashionable in Europe. Its chief characteristics were a critical stance towards classical European philosophy and its systems, and towards traditional academic discourse more generally. Instead, philosophy was to become more personal, closer to the senses of life itself. In France and Germany especially, authors such as Henri Bergson and Georg Simmel focused on such ideas as the perception of time and the sense of self. Against this light, some aristocratic writers specialized in being aristocratic.

In the ideological formation of fascism and National Socialism, transnational elite communities played an ambivalent role. They were facilitators of these new ideological movements in their earlier phases, as Chapter 6 shows. But as discussed in Chapter 7, they were equally important for the cultural formation of dissident communities whose transnational ethos had formed from sympathy with causes such as the critique of the Versailles peace treaty, the republicanism of the Spanish Civil War, or international anti-fascism. The task of this book is not to evaluate the relative complicity of the old elites in revolutions or reaction. Rather, the transnational perspective served as a tool for elucidating the degree to which post-imperial transformation as a process crossed established political as well as geographic frontiers. The ideas and emotions of these Europeans belong to the cultural prehistory of European integration as it began with the Rome agreements of 1957.Footnote 78

Towards a transnational and synaesthetic archive

My approach to the study of the survival of imperial and inter-imperial memory in post-imperial Europe was transnational in scope, which also meant that I sought to give equal weighting to diplomatic and government archives as I did to private archives and the archives of organizations such as the publishing houses. It was characteristic of imperial archives and their national successors alike to be extremely shrewd about controlling their own memory. The way to read against their archives is to look at archives gone out of control, in a sense: personal archives which contradict the logic of national and imperial borders, just as particular lives rarely coincide with state borders for instance. Fragments of multiple imperial and national archives have found their way by accident or by design to such places of purchased memories as the archives of the Hoover Institution and some American university libraries, or the archives which the Nazi government confiscated across Europe, which were subsequently confiscated by the Soviet army and are now housed in Moscow’s special collections. In addition, the living memory of people today, accessible through recorded conversations and by email, is another source of knowledge about the past. This archive contains a multidirectional memory in which multiple empires blend into one concoction.

European political thought of this period was a product not only of rival political languages and philosophies but also of spontaneous speech and unfinished processes of thinking. It was also visibly synaesthetic, considering that thinking about post-imperial transformation happened in the age of new media such as radio and later film, as well as the illustrated press. These were not just new modes of reproducing and sharing information but also media for sharing emotions and common sensibilities. By the late 1920s, recorded sound and visual flashbacks of a reimagined historical past formed an irreducible part of not only present discourse but also ongoing political conflicts.

My interest in focusing on medium-sized periodicals was to capture the difference between the expression of uncertainty towards the viability of revolutions and the inability to express certain judgements about a political situation.Footnote 79 The intellecuals in the network whose importance I highlight were critical of empires and uncertain of revolutions, but there was no ambiguity in their judgement of politics or aesthetics. Politically eclectic, the periodicals to which they contributed created a kind of musée imaginaire of imperial memories in which one common theme prevailed: the idea that empires had offered them a multicultural way of life, which they were sorry to lose.Footnote 80 Here, emotions were shared and allowed readers and subscribers to form connections that only partially overlapped with ideologies.Footnote 81 These Europeanist journals reinterpreted the old German dichotomy of Kultur versus Zivilisation by reapplying it to Europe and its ‘others’.Footnote 82 Journals of this kind are the closest non-oral medium which allows us to capture the importance of thinking in groups, and the fact that some ideas cannot be reduced to the work of individual authors.Footnote 83

The contributions of the German-speaking elites of Europe provide the theoretical response to the works of fiction written in Europe, in which disorientation itself is the main theme. In these witness accounts and works of fiction, a clear hero is absent, traditional forms and scales of representation were replaced with new forms of representing sound and vision. They spoke of a ‘dusk of humanity’, of a ‘decline of the West’, and a European wasteland.Footnote 84 The newly found charisma of decline exhibited by the German intellectuals provided a kind of political facework in the age of imperial effacement.Footnote 85

The book is organized around the moments and events, which are significant for the discursive sphere of these intellectual communities. These are determined by key moments of historical or remembered experience, when the European empires were under threat, and in which representatives of Germanic dynasties or German imperial elites emerge as central figures of decline. They do not necessarily correspond to a more familiar narrative of twentieth-century European history in this period. The first event is 1867, the year when the Habsburg ‘puppet’ emperor Maximilian loses his life to Mexican republicans. At the same time, in Europe, Austria concedes to a share of power with the Kingdom of Hungary, changing the constitution of rule in the Habsburg Empire into a Dual Monarchy. For the intellectuals discussed here, such events were remembered as part of their personal intellectual formation. Other post-imperial moments include the memory of public events such as the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, but also more personal experiences of revolution around the years 1917–20, when the Russian and German empires disintegrated. The analysis concludes with the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, when Anglo-American intellectuals and public figures propose a framework for reconstructing the idea of Europe in the wake of Germany’s defeat. The book invites a new perspective on Europe in the period between 1917 and the history of Europe’s institutional and economic integration associated with the Treaty of Rome of 1957. During this time, a German-speaking liberal fraction wove their experience of revolution into a common European memory of empire. In what follows, I hope to show what was characteristic of their mentality, how this network was formed, and the many individuals and groups belonging to this circle who were subsequently forgotten.

1 For more on Brest-Litovsk before the war, see Kh. Zonenberg, Istoria goroda Brest-Litovska. 1016–1907, etc. [History of the city of Brest-Litovsk] (Brest-Litovsk: Tipografia Kobrinca, 1908).

2 There is, of course, a very large literature on the Russian Revolution and Civil War. To indicate directions which are important to the present book, I concentrate on references to works which link the revolution to processes of imperial decline and war and put these in comparative perspective. See especially Mark von Hagen, ‘The Russian Empire’, and Ronald G. Suny, ‘The Russian Empire’, in After Empire. Multiethnic Societies and Nation-Building. The Soviet Union and the Russian, Ottoman, and Habsburg Empires, ed. Karen Barkey and Mark von Hagen (Boulder: Westview Press, 1997), 58–73 and 142–155; James D. White, ‘Revolutionary Europe’, in A Companion to Modern European History. 1871–1945, ed. Martin Pugh (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997), 174–193; for revolution as a consequence of war, see Peter Gatrell, Russia’s First World War: A Social and Economic History (London and New York: Routledge, 2005); and Katja Bruisch and Nikolaus Katzer, Bolshaia voina Rossii: Sotsial’nyi poriadok, publichnaia kommunikatsia i nasilie na rubezhe tsarskoi i sovetskoi epochi (Moscow: NLO, 2014). For a comparative and theoretical perspective, see the classic by Theda Skocpol, States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia, and China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), and Charles Tilly, European Revolutions, 1492–1992 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993). For a more comprehensive literature, see Jonathan Smele (ed. and annot.), The Russian Revolution and Civil War, 1917–1921: An Annotated Bibliography (London and New York: Continuum, 2003).

3 John Reed, Ten Days That Shook the World (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1919); on the history of the revolution as a story, see Frederick C. Corney, Telling October: Memory and the Making of the Bolshevik Revolution (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004).

4 Lenin’s commentary on Hobson was first published as Nikolai Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (Petrograd: Zhizn’ i Znanie, 1917).

5 For the intellectual and practical transition via ‘imperial citizenship, see Daniel Gorman, Imperial Citizenship: Empire and the Question of Belonging (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006). See also Elleke Boehmer, Empire, the National and the Postcolonial, 1890–1920. Resistance in Interaction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

6 Stefan Zweig, Marie Antoinette: The Potrait of an Average Woman (New York: Garden City Publishing Co., 1933).

7 Cf. Christoph Kopke and Werner Treß (eds.), Der Tag von Potsdam (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2013).

8 Cf. Larisa Reisner, Hamburg auf den Barrikaden. Erlebtes und Erhörtes aus dem Hamburger Aufstand 1923 (Berlin: Neuer Deutscher Verlag, 1923).

9 Cf. Richard Watt, The Kings Depart: The Tragedy of Germany. Versailles and the German Revolution (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968). For a more balanced recent account of the revolutions in Germany, see Richard Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich (London: Penguin, 2003), and Christopher Clark, Introduction to Viktor Klemperer, Victor Klemperer, Man möchte immer weinen und Lachen in Einem. Revolutionstagebuch 1919 (Berlin: Aufbau, 2015).

10 See Gregory Claeys, The French Revolution Debate in Britain: The Origins of Modern Politics (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007).

11 Otto Neurath, Gesellschaft und Wirtschaft. Bildstatistisches Elementarwerk. Das Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum in Wien zeigt in 100 farbigen Bildtafeln Produktionsformen, Gesellschaftsordnungen, Kulturstufen, Lebenshaltungen (Leipzig: Bibliographisches Institut, 1930).

12 Hermann Keyserling, Reise durch die Zeit (Vaduz: Liechtenstein, 1948), 53.

13 Noel Annan, ‘The Intellectual Aristocracy’, in Studies in Social History, ed. John Plumb (London: Longmans, 1955).

14 Clifford Geertz, ‘Centers, Kings, and Charisma: Reflections on the Symbolics of Power’, in Culture and Its Creators. Essays in Honor of Edward Shils, ed. Joseph Ben-David and Terry Nichols-Clark (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1971), 150–171.

15 Classic examples are Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France (London: J. Dodsley, 1790), and William Wordsworth, Tract on the Convention of Sintra (1808) (London: Humphrey Milford, 1915), as discussed in Michael Hechter, Alien Rule (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 1. For a problematization of the conservative/progressive optic in the intellectual history of revolutionary periods, see Richard Bourke, Empire and Revolution: The Political Life of Edmund Burke (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 1–23, and an unpublished paper, ‘Edmund Burke and the Origins of Conservatism’ (2015).

16 Michael Freiherr von Taube, Der großen Katastrophe entgegen. Die russische Politik der Vorkriegszeit und das Ende des Zarenreiches (1904–1917) (Berlin and Leipzig: Georg Neuner, 1929), 1.

17 His own reflections comprise Michael Freiherr von Taube, Rußland und Westeuropa (Rußlands historische Sonderentwicklung in der europäischen Völkergemeinschaft), Institut für internationales Recht an der Universität Kiel (Berlin: Stilke, 1928); and Prof. bar. M.A. Taube, Vechnyi mir ili vechnaia voina? (Mysli o „Ligi Natsii“) (Berlin: Detinets, 1922).

18 Donald Winnicott, The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development (1965; London: Karnac Press, 1990).

19 ‘Menaced with Extinction by War: European Bison in Lithuania’, Illustrated London News, 4 September 1915, 299.

20 Hobson, Imperialism, 35.

21 On the German distinction between Kultur and Zivilisation, see Raymond Geuss, ‘Kultur, Bildung, Geist’, in Morality, Culture, History, ed. Raymond Geuss (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 29–51.

22 See, notably, C.A. Bayly, Imperial Meridian: The British Empire and the World 1780–1830 (London: Longmans, 1989); Jennifer Pitts, A Turn to Empire. The Rise of Imperial Liberalism in Britain and France (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005); David Armitage, Foundations of Modern International Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

23 For a much grander nineteenth-century global history of empires, see Jürgen Osterhammel, The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), esp. 419–468.

24 On the transnational character of imperial formations, see Ilya Gerasimov, Sergey Glebov, Jan Kusber, Marina Mogilner, and Alexander Semyonov, Empire Speaks Out. Languages of Rationalization and Self-Description in the Russian Empire (Leiden: Brill, 2009).

25 I take the view that the radical thinkers of the enlightenment were generally less characteristic of the concept, at least in the way it was received subsequently, than Jonathan Israel has tended to present it. For the original statement of the ‘radical enlightenment’ thesis, see Jonathan Israel, Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity, 1650–1750 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001). For a critique of this view, see David Sorkin, The Religious Enlightenment: Protestants, Jews, and Catholics from London to Vienna (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011).

26 Mehemed Emin Effendi, Civilisation et humanité, Introduction G. Ficker (Paris: G. Fickler, 1920), i–iv.

27 This phrase was first used in comparative perspective by W.B. Yeats in ‘Second Coming’, first published in W.B. Yeats, Michael Robartes and the Dancer (Dublin: Cuala Press, 1920). According to the manuscripts, Yeats’s original draft of the poem included references to the French and the Russian revolutions, but in the final version, only the Irish one remains. For details, see Thomas Parkinson and Anne Brannen (eds.), ‘Michael Robartes and the Dancer’ Manuscript Materials (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994). Significantly for the literature on decolonization, the line ‘things fall apart’ only became appropriated in the anticolonial literary movement associated with Chinua Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart (London: William Heinemann, 1958).

28 On the key sites where self-determination and home rule were discussed, see Mahatma Gandhi, ‘Hind Swaraj’, Indian Opinion, 11 and 18 December 1909; Woodrow Wilson, speech of 11 February 1918; the Bolshevik peace plan, 29 December 1918; for more context, see Alvin Jackson, Home Rule. An Irish History, 1800–2000 (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2003). For the Wilsonian conception of self-determination and its global effects, see Erez Manela, The Wilsonian Moment. Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

29 The classic critique of imperialism deceiving the imperialists is John Hobson, Imperialism. On the concept of alien rule, see John Plamenatz, On Alien Rule and Self-Government (London: Longmans, 1960), and Hechter, Alien Rule. On decolonization in comparative perspective, see especially Martin Thomas, Bob Moore, and L.J. Butler (eds.), Crises of Empire. Decolonization and Europe’s Imperial States, 1918–1975 (London: Hodder, 2008); Frederick Cooper, ‘Decolonizing Situations: The Rise, Fall, and Rise of Colonial Studies, 1951–2001’, in French Politics, Culture & Society, 20:2, Special Issue: Regards Croisés: Transatlantic Perspectives on the Colonial Situation (Summer 2002), 47–76. See also Ronald Robinson, ‘Non-European Foundations of European Imperialism: Sketch for a Theory of Collaboration’, in Roger Owen and Bob Sutcliffe (eds.), Studies in the Theory of Imperialism (London: Longman, 1972), 117–140.

30 ‘Deklaratsia prav narodov Rossii’ (2/15 November 1915) and ‘Dekret ob unichtozhenii soslovii i grazhdanskikh chinov’ (11/24 November 1917), in Dekrety sovetskoi vlasti (Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe izdatelstvo politicheskoi literatury, 1957), 39–40 and 72.

31 On the changing image of the Romanoffs during the war, see Boris Kolonitskii, Tragicheskaya erotika. Obrazy imperatorskoi sem’i v gody Pervoi mirovoi voiny (Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, 2010).

32 On the concept of internal colonization, cf. Michael Hechter, Internal Colonialism. The Celtic Fringe in British National Development (1975, new edition, New Brunswick: Transaction, 1999). As applied to the Russian Empire, see Alexander Etkind, Ilya Kukulin, and Dirk Uffelmann (eds.), Tam, vnutri. Praktiki vnutrennei kolonisatsii v kul’turnoi istorii Rossii (Moscow: NLO, 2012), and Alexander Etkind, Internal Colonization: Russia’s Imperial Experience (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011).

33 Concerning the decree 13 ‘On Turkish Armenia’, Pravda (29 December 1917), see Serif Mardin, ‘The Ottoman Empire’, in After Empire. Multiethnic Societies and Nation-Building. The Soviet Union and the Russian, Ottoman, and Habsburg Empires, ed. Karen Barkey and Mark von Hagen (Boulder: Westview Press, 1997), 115–128, and Michael A. Reynolds, Shattering Empires. The Clash and Collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires, 1908–1918 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 179.

34 On shattered hopes in the Bolshevik party as a vanguard of emancipation, particularly as expressed among the European left in the 1920s, see especially Pyotr Kropotkin, ‘The Russian Revolution and the Soviet Government. Letter to the Workers of the Western World’, in Labour Leader (22 July 1920), reprinted in Kropotkin’s Revolutionary Pamphlets, ed. Roger Baldwin (1927) (New York: Dover, 1970), 252–256; see also Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, 50 (1923), referring back to Robert Michels, Zur Soziologie des Parteiwesens in der modernen Demokratie (Leipzig: Klinkhardt, 1911). On betrayals of the party from within in the crisis of the First World War, Grigory Zinoviev, Der Krieg und die Krise des Sozialismus (Vienna: Verlag für Literatur und Politik, 1924).

35 On the changing concept of terror in the course of the revolution, see Oleg Budnitsky, Terrorizm v rossiiskom osvoboditel’nom dvizhenii (Moscow: Rosspen, 2000).

36 Manela, Wilsonian Moment.

37 See National Archives, HO 342,469/13, Letter from Lloyd George to the Secretary of State of 29 August 1915, in ‘Titles, Styles and Precedence of Members of the Royal Family: Relinquishment of German Titles in Favour of British Titles; Adoption of Surnames Mountbatten and Windsor; Principles of Entitlement to the Style “Royal Highness” and the Case of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor (1917–48)’, www.heraldica.org/topics/britain/TNA/HO_144_22945.htm, accessed 5 July 2015. On the wider British context, see Alan G.V. Simmonds, Britain and World War One (London and New York: Routledge, 2012).

38 For a comprehensive account of this social history, see Lucy Elisabeth Textor, Land Reform in Czechoslovakia (London: G. Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1923); Eagle Glassheim, Noble Nationalists. The Transformation of the Bohemian Aristocracy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005); for an overview of the aristocracy in comparative perspective prior to 1914, see Dominic Lieven, The Aristocracy in Europe 1815–1914 (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992); for the later twentieth century, see Heinz Reif, Adel im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2012); for sociological and anthropological perspectives, see Monique de Saint Martin, L’espace de la noblesse (Paris: Éditions Métailié, 1993); Sofia Tchouikina, Dvorianskaia pamiat’: ‘byvshye’ v sovetskom gorode (Leningrad, 1920e–30e gody) (St. Petersburg: Izd-vo Evropeiskogo universiteta v StPb, 2006); Longina Jakubowska, Patrons of History. Nobility, Capital and Political Transitions in Poland (London: Ashgate, 2012).

39 The best analysis is from a sociologist of the Weber circle: Franz Carl Endres, ‘Soziologische Struktur und ihr entsprechende Ideologien des deutschen Offizierkorps vor dem Weltkriege’, in Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, 58:1 (1927), 282–319.

40 For a social liberal German perspective on the revolution, see Walther Rathenau, La triple revolution, transl. David Roget (Paris-Basel: Éditions du Rhin, 1921), esp. 332–333; for an anti-liberal global perspective, see Oswald Spengler, Der Mensch und die Technik (Munich: Beck, 1931).

41 For a critical German perspective on this post-war settlement, see Maximilian Graf Montgelas, Leitfaden zur Kriegsschuldfrage (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1923); and Das deutsche Weißbuch über die Schuld am Kriege mit der Denkschrift der deutschen Viererkommission zum Schuldbericht der Alliierten und Assoziierten Mächte (Charlottenburg: Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft für Politik und Geschichte, 1919).

42 Cf. John N. Horne and Alan Kramer, German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), ch. 9, ‘The Moral Reckoning’, 329–365; Isabel V. Hull, ‘The “Belgian Atrocities” and the Laws of War on Land’, in Hull, A Scrap of Paper. Breaking and Making International Law during the Great War (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2014), 51–95.

43 For the best-known critique, see John Maynard Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (London: Macmillan, 1919).

44 For ‘special path’ explanations of National Socialism in intellectual history, see Kurt Sontheimer, Antidemokratisches Denken in der Weimarer Republik (Munich: Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung, 1962), which also contains references to significant scholarship in this direction from the 1940s, and an earlier version in Kurt Sontheimer, ‘Antidemokratisches Denken in der Weimarer Republik’, in Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, 5:1 (January 1957), 42–62. For the ‘Weimar’ context of this argument, see Karl Mannheim, ‘Das konservative Denken I. Soziologische Beiträge zum Werden des politisch-historischen Denkens in Deutschland’, in Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, 57:1 (1927), 68–143. For statements of the ‘special path’ in social history, see Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte, vols. 3 and 4 (Munich: Beck, 1995, 2003), and Norbert Elias, Studien über die Deutschen. Machtkämpfe und Habitusentwicklung im 19. und 20. Jh. (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1989). On reunification as return to normality, see Konrad Jarausch, Die Umkehr. Deutsche Wandlungen 1945–1995 (Munich: DVA, 2005). For critiques of the special path, see David Blackbourn and Geoff Eley, Mythen deutscher Geschichtsschreibung. Die gescheiterte bürgerliche Revolution von 1848 (Frankfurt/Main: Ullstein, 1980). On German social and intellectual history in global perspective, Jürgen Osterhammel and Sebastian Conrad (eds.), Das Kaiserreich Transnational: Deutschland in der Welt, 1871–1914 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2004), 1–29. For an overview of the aftermath of the special path after German unification, see Helmut Walser Smith, ‘When the Sonderweg Debate Left Us’, in German Studies Review, 31:2 (May 2008), 225–240.

45 Max Weber, Politik als Beruf, Series Geistige Arbeit als Beruf. Vier Vorträge vor dem Freistudentischen Bund. Zweiter Vortrag (Munich: Duncker & Humblot, 1919). Hereafter cited as Max Weber, ‚Politik als Beruf’, from MWG I:17, 157–255.

46 For a classic expression of this view, see Max Weber’s inaugural lecture, Der Nationalstaat und die Volkswirtschaftspolitik (Freiburg: Mohr, 1895). On the relationship between economic and political theory, see also Max Weber, ‘Die “Objektivität” sozialwissenschaftlicher und sozialpolitischer Erkenntnis’, Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, 19 (1904), 22–88.

47 For a historical reconstruction of this genealogy, see Quentin Skinner, The Foundations of Modern Political Thought, vol. 2, The Age of Reformation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), 352. See also ‘From the State of Princes to the Person of the State’, in Skinner (ed.), The Foundations of Modern Political Thought, 368–414.

48 Quentin Skinner, ‘The Art of Theory’, conversation with Teresa Bejan (2013), in www.artoftheory.com/quentin-skinner-on-meaning-and-method/, accessed 4 March 2015.

49 For a more recent example of this approach, see Michel Foucault, « Il faut défendre la société », Cours au collège de France (1975–1976) (Paris: Gallimard, 1997).

50 Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morality (1887), ed. Keith Ansell-Pearson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), Essay 1.

51 One of his key sources is Sir Henry Sumner Maine, Lectures in the Early History of Institutions (London: John Murray, 1905), dealing with Irish law, clan law, and spaces of law beyond Roman law.

52 Weber, ‘Politik als Beruf’, 183.

53 Cf. Eckart Conze, ‘Noblesse oblige’, in Conze, Kleines Lexikon des Adels. Titel, Throne, Traditionen (Munich: Beck, 2005), 88. See also A. Graf Spee, ‘Adel verpflichtet (betr. Aufgaben des Adels in 1920)’, in Deutsches Adelsblatt, xxxviii (1920), 115.

54 Weber, ‘Politik als Beruf’, 227; see also Max Weber, Wahlrecht und Demokratie in Deutschland (Berlin: Fortschritt, 1918), in MWG I/15, 344–396, 374. On aristocratic honour codes and duels, see Hans Hattenhauer (ed.), Allgemeines Landrecht für die Preußischen Staaten von 1794, 3rd ed. (Munich: Luchterhand, 1996), XX, § 678–690. See also entires on ‘Adelsrecht’, ‘Duell‘, ‘Ehre’, in Conze, op cit.

55 Weber, ‘Politik als Beruf’, 242.

56 This phrase is used in David D’ Avray, Rationalities in History. A Weberian Essay in Comparison (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 5.

57 Weber, ‘Politik als Beruf’, 174.

58 Footnote Ibid., 66–74.

59 Max Weber, Economy and Society, ed. Guenther Roth and Klaus Wittich, vol. 2 (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1978), 1143. On male fraternities and warrior clans, 1144.

60 Footnote Ibid., 1135.

61 Footnote Ibid., vol. 1 321.

62 Georg Simmel, ‘Zur Soziologie des Adels. Fragment aus einer Formenlehre der Gesellschaft’, in Frankfurter Zeitung und Handelsblatt (Neue Frankfurter Zeitung), 52:358, 1, Morgenblatt, 27 December 1907, Feuilleton-Teil, 1–3, http://socio.ch/sim/verschiedenes/1907/adel.htm, accessed 25 March 2012.

63 Simmel, ‘Zur Soziologie des Adels. Fragment aus einer Formenlehre der Gesellschaft’, 1, Morgenblat, 27 December 1907, Feuilleton-Teil, 1–3.

64 Das deutsche Weissbuch über die Schuld am Kriege mit der Denkschrift der deutschen Viererkommission zum Schuldbericht der Alliierten und Assoziierten Mächte, ed. Auswärtiges Amt [German Foreign Office] (Charlottenburg: Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft für Politik und Geschichte, m.b.H., 1919).

65 Marianne Weber, Max Weber, 611. Max Weber, ‘Vorträge während der Lauensteiner Kulturtagungen 30. Mai und 29. Oktober 1917’, in MWG I/15, 701–707.

66 Vilfredo Pareto, The Mind and Society, transl. Arthur Livingston, 4 vols., vol. 3 (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1935), 1423.

67 Vilfredo Pareto, Trattato Di Sociologia Generale, 4 vols. (Florence: G. Barbera, 1916).

68 Vilfredo Pareto, The Mind and Society (1916), transl. Arthur Livingston, vol. 3 (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1935), 1430; Robert Michels, Political Parties. A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy (1911; New York: Hearst’s International Library, 1915), 377–393. On class as second skin rather than position, see Gareth Stedman Jones’s Languages of Class: Studies in English Working Class History, 1832–1982 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

69 Cf. Antonio Gramsci (ed.), L’Ordine Nuovo (1919–22). On hegemony and the intellectuals, see Antonio Gramsci, ‘The Formation of the Intellectuals’, in Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, Quintin Hoare and Jeffrey Nowell Smith (eds.) (New York: International Publishers, 2010), 5–17.

70 Hans Kelsen, ‘Recognition in International Law: Theoretical Observations’, in The American Journal of International Law, 35:4 (October 1941), 605–617.

71 In German, English, and American historiography, the social psychology of revolution on the left and the right has typically focused on the non-elite agents of revolutions. See the classic anti-liberal and anti-democratic view by Gustave Le Bon, The Psychology of Revolution (1911), Engl. transl. Bernard Miall (London: Allen & Unwin, 1913); Alexandre Kojève, Introduction to the Reading of Hegel. Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit (1947; New York: Basic Books, 1980); in the later twentieth century, structuralist theories of revolution moved away from psychological perspectives altogether, but continued to foreground patterns which enable revolutionaries to act. See, for instance, Skocpol, States and Social Revolutions. A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia and China. After this, theories of recognition replaced theories of revolution, but again focused on the recognition of formerly not recognized subjects, rather than what happened to the newly derecognized elites. Cf. Charles Taylor, ‘The Politics of Recognition’, in Taylor, Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition, ed. Amy Gutmann (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), or Nancy Fraser and Axel Honneth, Redistribution or Recognition? A Political-Philosophical Exchange (London: Verso, 2003).

72 First formulated in 1922, it reached a wider English-speaking audience in the 1930s. See Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi, ‘The Pan-European Outlook’, in International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1931–1939), 10:5 (September 1931), 638–651.

73 J.A. Hobson, review of Count R.N. Coudenhove-Kalergi, Man and the State, Manchester Guardian, 20 December 1938, 7.

74 Douglas Smith, Former People: The Last Days of the Russian Aristocracy (New York: Macmillan, 2012).

75 For a clearer understanding of the ‘former people’, see Sofia Tchouikina, Dvorianskaia pamiat’: ‘byvshye’ v sovetskom gorode (Leningrad, 1920e – 30e gody) (St. Petersburg: Izd-vo Evropeiskogo universiteta v StPb, 2006). For social status and the construction of social reality, see John R. Searle, The Construction of Social Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1995), and Charles Taylor, The Sources of the Self (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1989).

76 Karl Kraus, ‘Der Adel von seiner schriftstellerischen Seite’, in Die Fackel, XXVII (1925), 137.

77 On dilettantism, see Pierre Bourdieu, Les règles de l´art. Genèse et structure du champ littéraire (Paris: Seuil, 1998); With regard to the literature of the 1920s, see Boris Maslov, ‘Tradicii literaturnogo diletantisma i esteticheskaia ideologia romana “Dar”’, in Yuri Levin and Evgeny Soshkin (eds.), Imperia N. Nabokov I nasledniki (Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2006), 37–73. See also H. Rudolf Vaget, ‘Der Dilettant: eine Skizze der Wort- und Begriffsgeschichte’, in Jahrbuch der deutschen Schillergesellschaft, 14 (1970), 131–158, and Benno von Wiese, ‘Goethes und Schillers Schemata über den Dilettantismus’, in von Wiese, Von Lessing bis Grabbe: Studien zur deutschen Klassik und Romantik (Düsseldorf: Babel, 1968), 58–107.

78 For a genealogy of ideas about Europe, see Anthony Pagden (ed.), The Idea of Europe: from Antiquity to the European Union (Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002). For an institutional history of European integration policy, see Wolfram Kaiser and Jan-Henrik Meyer, Societal Actors in European Integration: Polity-Building and Policy-Making 1958–1992 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). On the intellectual history of European reconciliation in transnational context, see especially Vanessa Conze, Das Europa der Deutschen. Ideen von Europa in Deutschland zwischen Reichstradition und Westorientierung (1920–1970) (Oldenbourg: Institut für Zeitgeschichte, 2005); Guido Müller, Europäische Gesellschaftsbeziehungen nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg das Deutsch-Französische Studienkomitee und der Europäische Kulturbund (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2005); Mark Hewitson and Matthew D’ Auria (eds.), Europe in Crisis. Intellectuals and the European Idea, 1917–1957 (Oxford: Berghahn, 2012); Wolfram Kaiser, Christian Democracy and the Origins of European Union (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).