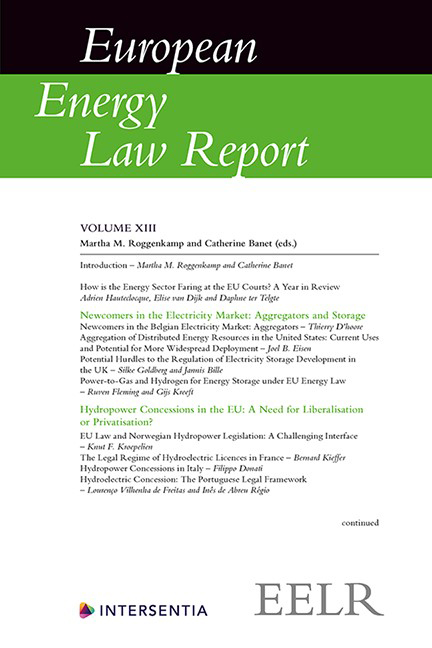

Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Preface

- Contents

- List of Abbreviations

- List of Contributors

- Introduction

- Chapter I How is the Energy Sector Faring at the EU Courts? A Year in Review

- PART I NEWCOMERS IN THE ELECTRICITY MARKET: AGGREGATORS AND STORAGE

- PART II HYDROPOWER CONCESSIONS IN THE EU: A NEED FOR LIBERALISATION OR PRIVATISATION?

- PART III INVESTMENTS AND DISINVESTMENTS IN THE ENERGY SECTOR

- PART IV OFFSHORE DECOMMISSIONING IN THE NORTH SEA

- PART V CCS AS A CLIMATE TOOL: NORTH SEA PRACTICE

- PART VI FROM EU CLIMATE GOALS TO NATIONAL CLIMATE LAWS

Chapter V - Power-to-Gas and Hydrogen for Energy Storage under EU Energy Law

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 30 April 2020

- Frontmatter

- Preface

- Contents

- List of Abbreviations

- List of Contributors

- Introduction

- Chapter I How is the Energy Sector Faring at the EU Courts? A Year in Review

- PART I NEWCOMERS IN THE ELECTRICITY MARKET: AGGREGATORS AND STORAGE

- PART II HYDROPOWER CONCESSIONS IN THE EU: A NEED FOR LIBERALISATION OR PRIVATISATION?

- PART III INVESTMENTS AND DISINVESTMENTS IN THE ENERGY SECTOR

- PART IV OFFSHORE DECOMMISSIONING IN THE NORTH SEA

- PART V CCS AS A CLIMATE TOOL: NORTH SEA PRACTICE

- PART VI FROM EU CLIMATE GOALS TO NATIONAL CLIMATE LAWS

Summary

INTRODUCTION

Power-to-Gas and hydrogen are becoming prominent topics in debates on the design of future energy systems. The technology is gaining popularity amongst the energy industry and energy regulators alike, as highlighted by the increasing policy research in this field. The reason for this popularity is the flexible and versatile way in which the technology could facilitate the ongoing energy transition.

Power-to-Gas could be used for a number of purposes, but one of the most promising is the storage of surplus electricity from renewable energy installations. In this way renewable energy could be stored and the time of use can be inferred. This would be helpful to counter the naturally intermittent production pattern of renewable energy installations, which do not produce (and thus do not feed electricity into the system) when the sun does not shine and the wind does not blow. In these situations the electricity has to be balanced, which at the moment means that coal and gas-fired power plants have to make up for temporary shortages in renewable energy generation. Storing electricity via Power-to-Gas could be a long-term option to counterbalance seasonal differences (strong winds in autumn, but not in summer). The current chapter will specifically focus on this promising potential of Power-to-Gas as a means to store electricity to counter this intermittence issue.

Current numbers, however, are rather sobering, as 96 per cent of hydrogen at the moment is produced from fossil fuels through methane steam reforming, according to the International Energy Agency. This process generates greenhouse gases in significant quantities.

By contrast, merely four per cent of hydrogen is derived from renewable sources via electrolysis. This hydrogen, produced from renewable energy sources, is referred to as ‘green hydrogen’, while hydrogen produced from fossil fuels, is called ‘grey hydrogen’.

When zooming in on ‘green’ hydrogen, we can see that it has two main sources. First, biomass-based production and second, water-electrolysis based on electricity from renewable sources, also known under the term ‘Power-to-Gas’. According to Ball/Seydel/Wietschel/Stiller, offshore wind via electrolysis/ Power-to-Gas can play a very important role in hydrogen production after 2020 and become its main source. This, however, will depend on technical advances as well as a clear legal framework for the technology.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- European Energy Law Report XIII , pp. 101 - 124Publisher: IntersentiaPrint publication year: 2020

- 5

- Cited by