Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Ethical and the Image

- 2 The Image and the Body

- 3 The Body and the Camera

- 4 Literal Durations and Cinematic Parallelism

- 5 The Inhuman Eye and the Formless Body

- 6 Re-enactment, Proxies and the Facing Image

- 7 The Withdrawal of the Body

- 8 The Offscreen and the Promise of the Image

- Coda

- Bibliography

- Index

5 - The Inhuman Eye and the Formless Body

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 March 2025

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Ethical and the Image

- 2 The Image and the Body

- 3 The Body and the Camera

- 4 Literal Durations and Cinematic Parallelism

- 5 The Inhuman Eye and the Formless Body

- 6 Re-enactment, Proxies and the Facing Image

- 7 The Withdrawal of the Body

- 8 The Offscreen and the Promise of the Image

- Coda

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Emmanuel Levinas associates the image with form and violence. Significantly, he sees this violence already embedded within objecthood: ‘the forms of objects call for the hand and the grasp. By the hand the object is in the end comprehended, touched, taken, borne and related to other objects.’ Levinas continues: ‘Beneath form, things conceal themselves.’ The object, insofar as it is nothing but the form it leaves and offers, has in its structure a call to grasp; perhaps somehow before there is a consciousness to assume the hand to grasp. The gaze is a hand that reaches out to grasp the object and, most importantly, is always already characterised by its eventual return to the same/familiar, by the solace of a return home. The gaze, as Hagi Kenaan remarks, ‘zealously preserves closure as a condition of self-identity, without any possibility of opening up to a radical outside’.

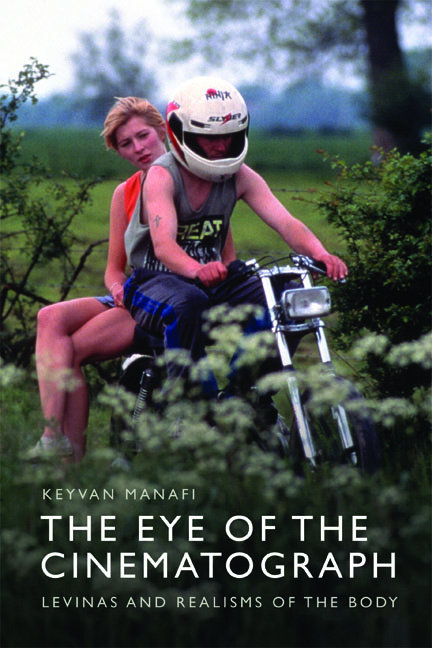

What if, however, the gaze is already altered when the cinematic image visits the eye; that there is a certain formlessing already at work before there is an eye that recognises and forms? Dziga Vertov eminently observes that the cinematographic camera, what he termed kino-eye, not only perceives more and better (than the human eye) but is also a potentiality, a capacity to be fostered: ‘We cannot improve the making of our eyes, but we can endlessly perfect the camera.’ At the core of this machine resides a preoccupation with the filmed body. Through the automatic formation of the body's image, the camera says ‘yes’ to the body of the other and welcomes it before an identification of the body. Without discrimination, the camera hosts the body of the visitor. It receives the body and affirms its presence without expectation. The filmed body is therefore assumed before there is a subject to accept the body. In a certain sense, the body of the other has arrived in the absence of an authority to invite the body to be made present. What precedes is not a body that is readily recognisable as tied to intentional meanings. The inhuman eye of the camera transfers the body of the other without interrogating what the body is or signifies.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Eye of the CinematographLévinas and Realisms of the Body, pp. 123 - 153Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2023