1 Biography

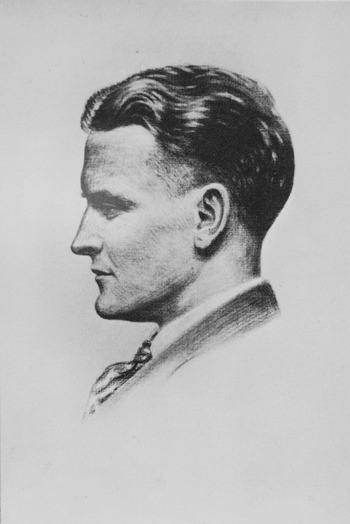

Fitzgerald (Figure 1.1.) participated unreservedly in the world he wrote about. He saw his life as a vivid example of American aspirational themes and as representative of a turning point in American history, the extreme prosperity and social changes of the 1920s followed by the Crash of 1929. In attaching himself so seamlessly to America’s grand mythology and depicting that mythology’s allure and corruption in his fiction, the link between life and work is not only appropriate; it is also key.1

Figure 1.1. F. Scott Fitzgerald, study by Gordon Bryant (Shadowland, January 1921).

Born in St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1896 to an Irish-Catholic family, Fitzgerald was named after a famous distant cousin, Francis Scott Key, author of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” His father’s inability to earn a reliable income caused the family to move around during Fitzgerald’s childhood, first to Buffalo, then Syracuse, then back to Buffalo, and finally back to St. Paul, where they would remain. The Summit Hill neighborhood in which he grew up included St. Paul’s social elite. Fitzgerald’s family, by contrast, once upper middle class, was now a family in decline, moving from one lackluster rental property to another while his classmates lived seemingly charmed lives in charmed houses that carried their family names. Although his mother’s inheritance provided the family with a comfortable life, Fitzgerald knew he had no family name or money to back him, and to compensate, he became an expert observer of markers of social class: differences in manners, taste, speech, and whether one projected confidence or insecurity. As Scott Donaldson argues in his biography of Fitzgerald, “he was driven to please other people,” and “he tried to prove his worth by exercising his charm.”2

Like most Americans, Fitzgerald believed in self-improvement, but he also believed that early experiences determined the fundamentals of character. In a letter to the Princeton Alumni Weekly in 1932, Fitzgerald expressed his conviction that the “salient points of character” were “fixed by the age of twelve,” and that “the deeper matters of whether [a person is] weak or strong, strict or easy with himself, brave or timid” were “arranged in the home, almost in the nursery” (qtd. in Donaldson, 179; emphasis added). Andrew Turnbull’s poignant memoir/biography, Scott Fitzgerald, provides an insightful rendering of two of Fitzgerald’s childhood memories that seem to have been formative. Twelve is exactly the age Fitzgerald was when his father, Edward, lost his job with Procter & Gamble, and he vividly remembered how traumatic this event was for him. “I felt that disaster had come to us,” Fitzgerald recalled: “‘Dear God,’ I prayed, ‘please don’t let us go to the poorhouse.’” He remembered his father had left home that morning “comparatively young” and “full of confidence” and had returned “a completely broken man.”3 In the same vein, Fitzgerald recalled an even earlier memory about a “nursery book” depicting a fight between “large animals, like the elephant” and “small animals, like the fox.” Even though the small animals were winning the battle at first, the large animals eventually overpowered them. Fitzgerald’s sympathies were with the fox. “I wonder if even then,” he said, “I had a sense of the wearing down power of big, respectable people. I can almost weep now when I think of that poor fox.” Fitzgerald believed that this story was “one of the big sensations” of his life, and he remembered how it had filled him “with the saddest most yearning emotion” (Turnbull 14). Fitzgerald’s father, a kind, well-mannered but defeated man, surely seemed to him like one of the small foxes, and being his father’s son put the younger Fitzgerald in a precarious situation from the beginning.

Whether Fitzgerald’s memory was actual or imagined, it nevertheless provides a basis for understanding his ambivalence about success. Although Fitzgerald always dreamed of being wildly successful, and in his early twenties realized that dream, it was the story of failure, not success, that appealed to him as a writer. Fitzgerald was as suspicious of making it big as he was desirous of it. When years later he would write in his notebook, “I talk with the authority of failure – Ernest [Hemingway] with authority of success” (N, no. 191, 318), he was not feeling sorry for himself so much as he was asserting the authenticity of his experience and vision as a writer. His distrust of American versions of success puts him in the same camp as other American writers whose work he knew well, writers such as Mark Twain, Henry James, Sherwood Anderson, and Theodore Dreiser. Fitzgerald’s most famous character, Jay Gatsby, embodies America’s divided nature, transcendental idealism versus the crass worship of success. Although Fitzgerald is a modernist writer, his conviction that the accidents of birth, the family and home one is born into, mold one’s character, which, coupled with his deeply ingrained vision of the powerful in society crushing the more vulnerable, account for the deterministic themes that persist in his fiction.

The role that Fitzgerald’s mother played in his early life was as uncomfortable for him as that of his father. Mollie Fitzgerald adored, pampered, and spoiled her only son. She also embarrassed him. When Fitzgerald’s pioneering biographer, Arthur Mizener, interviewed Fitzgerald’s childhood friends, they remembered Mollie “as a witchlike old lady who carried an umbrella, rain or shine.”4 She was also known to have worn one old shoe and one new shoe (each a different color) to a dressy social event because she wanted to break in one shoe at a time (Mizener 3). Such behavior must have horrified her son, who at the time wanted nothing as much as he wanted to be popular. He began putting on airs and imagined that he was secretly the son of royalty and that he had been dropped off on his parents’ doorstep by some stroke of misfortune.5 Fitzgerald enjoyed living in his imagination, creating idealized versions of himself, and inventing stories wherein he demonstrated courage, athletic prowess, and all manner of exceptional abilities.6

In addition to the rich world of his imagination, he also enjoyed a highly active social life in St. Paul: toboggan parties, dances, and playing post office with pretty girls. Even as a young boy, he knew he was handsome, and he felt that he was destined for something great. Mollie kept his baby book with loving care, recording the things he did and said as if each were exceptionally clever and important. A page entitled “Progressive Record of Autographs” in his baby book preserves a visual record of Fitzgerald’s invention of the person he wanted to become.7 His autograph at five is simply Scott, scrawled in large, uneven letters; soon he becomes Scott Fitzgerald, written in careful cursive. At age fifteen, he plays with signing his name Francis Scott Fitzgerald. At seventeen, he settles on F. Scott Fitzgerald, written in a more mature but still unremarkable hand. At age twenty-one, his name finally appears in the elegant, confident cursive he would use the rest of his life. This was the signature of what Fitzgerald called a “personage,” a person of distinction.

Well-off relatives paid Fitzgerald’s tuition so that he could attend private schools. A bright boy and an enthusiastic reader, he nevertheless did not like to study and was always a poor student. What he did like to do was write, and he began publishing stories in his school’s magazine when he was thirteen. Fitzgerald failed the admissions test to Princeton but was close enough to passing and persuasive enough to argue his way in. He soon fell in with a literary group as excited about literature as he was. He wrote poetry, plays, and stories for Princeton publications and the lyrics for two musicals for the Triangle Club. Poor grades disqualified him from being president of the Triangle Club, a position that he very much wanted. According to Matthew J. Bruccoli, his definitive biographer, “Fitzgerald established a pattern of having to make up for past failures while failing current courses. It was a predicament that would get worse every term.”8 He also lost the girl he had his heart set on winning. A Lake Forest, Illinois, socialite, Ginevra King was popular, pretty, and rich.9 Fitzgerald idealized her and conducted an ardent courtship mostly through letters. During the time of an unsatisfactory visit with Ginevra in Lake Forest near the end of their relationship, Fitzgerald overheard this comment that he recorded in his Ledger: “Poor boys shouldn’t think of marrying rich girls” (FSFL 170). Highly sensitive to rejection and class distinctions, Fitzgerald would always remember the role Ginevra’s wealth seemed to play in the breakup, and the corrupting power of money over love in American life became one of the great themes in his fiction.

Realizing he would not be graduating from Princeton, Fitzgerald joined the army and wrote melodramatic letters to his family, stating he felt certain that he would be killed in war. He also wrote an autobiographical novel, “The Romantic Egotist,” which, although the publisher encouraged him to revise and resubmit it, was still turned down. Fitzgerald’s disappointments – Princeton, Ginevra, his manuscript, and even his impending death – did not dampen his spirit for long. Although he had a self-confessed tendency to take disappointments hard, he was also often surprisingly resilient, even to the point of exuberance. For example, while waiting in New York to leave for training camp, Fitzgerald enjoyed a continuous round of parties. And while having a drink at the elegant Bustanoby’s on Broadway, he suddenly exhibited his elation by turning cartwheels from the bar all the way into the ladies’ room (Mizener 83).

His training camp was outside of Montgomery, Alabama, where he met Zelda Sayre, the most beautiful, sought-after girl in three states. Just two months after meeting Zelda, Fitzgerald wrote in his Ledger, “Sept: Fell in love on the 7th,” and on his birthday, he summed up his twenty-first year: “A year of enormous importance. Work, and Zelda. Last year as a Catholic” (FSFL 172–73). The essentials of his future – matters of vocation, love, and faith – had been decided. Fitzgerald saw in Zelda a spirit that matched his own, but unlike himself, Zelda seemed absolutely fearless, a trait he found especially attractive but also unsettling. After their marriage, as Zelda’s behavior became increasingly erratic, Fitzgerald would see those traits that originally charmed him in a different light. But he was at the time, as he would be throughout his life, firmly committed to Zelda. In a letter just prior to their marriage, Fitzgerald wrote this about his love of Zelda: “My friends are unanimous in frankly advising me not to marry a wild, pleasure loving girl like Zelda … but … I love her and that’s the beginning and end of everything” (C 53). Fitzgerald believed in romantic and lasting love even though he also believed that ugly money and class issues fought against it. Zelda reassured him that her passion matched his own: “Scott – there’s nothing in the world I want but you – and your precious love,” she wrote to him. “All the material things are nothing … Don’t ever think of the things you can’t give me. You’ve trusted me with the dearest heart of all.” (S&Z 15–16).

The war ended before Fitzgerald was scheduled to go overseas, and he went to New York to start a career, hoping to send for Zelda. He landed a job in advertising, hated it, and made very little money. Worst of all, he and Zelda seemed to have reached a dead end in their plans to be married. Fitzgerald went on a three-day bender, then went back home to St. Paul and, with astonishing discipline, revised his novel. Scribners immediately accepted the new version, and Fitzgerald was so ecstatic that he literally stopped strangers on the street to tell them that he was officially an author. This Side of Paradise is an autobiographical coming-of-age novel. It tells the story of a new generation liberated from their parents’ Victorian ideas, and it virtually became a handbook for the new ways of talking, dressing, and even thinking. Fitzgerald was not only an important new author; he was a spokesman for the new flappers and philosophers, an enfant terrible, and though he would later see the folly clearly, at the time, no one could have played this role better or enjoyed it more.

Once Fitzgerald’s novel was accepted for publication, Zelda quickly joined him in New York, where they were married at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Passionately in love, and giddy with sudden celebrity, the couple already exhibited unsustainable patterns: endless parties, drinking, reckless spending, and outrageous behavior designed to garner attention. In 1921, the Fitzgeralds went to Europe for the first time, and then they returned to St. Paul for the birth of their only child, Scottie, a healthy daughter with a cheerful disposition. But the Fitzgeralds continued to move restlessly about and never settled anywhere long enough to establish a real sense of home.

Fitzgerald’s second novel, The Beautiful and Damned (1922), lacks the vitality that runs through This Side of Paradise, but Fitzgerald wanted to develop new themes – the new novel presented a bleak portrait of a glamorous young married couple, Anthony and Gloria Patch, who, while waiting to inherit the Patch fortune, slip into dissipation and alcoholism. Anthony and Gloria represented New York’s young socialites who were turning the city into their playground. It is a cautionary story about waste, but it is also a portrayal of humiliation, an experience that Fitzgerald would come to know all too well because of his own alcoholism.

The Fitzgeralds moved to Great Neck, New York, hoping that Scott could settle into a productive writing routine. They continued their party life instead, and Fitzgerald’s drinking accelerated. He and Zelda were still viewed as beautiful young celebrities, but their extravagant lifestyle and the magazine stories Fitzgerald churned out to support it began to wear on him. Fitzgerald had a complex relationship with the magazines that published his stories. Their massive circulation contributed to his fame and success, and they paid well. Additionally, Scribners published a book of Fitzgerald’s stories after each novel; Fitzgerald, always borrowing against future work, needed additional income. Even though he often disparaged the stories, Fitzgerald produced approximately 175 of them, and they played an important role in his development as a writer. Many of his finest stories – “May Day,” “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz,” “Winter Dreams,” and “Babylon Revisited,” for example – remain a vital part of his canon. Still, he resented the time they took away from his work on his novels.10

The Fitzgeralds’ lives in Great Neck soon became so chaotic that they embarked on yet another geographic cure, this time to France, where Fitzgerald wrote his third novel, The Great Gatsby (1925), a beautifully crafted meditation on human longing. The Jazz Age setting contrasts with the imaginative promise the New World first represented. Gatsby’s (and early America’s) idealism gives way to rapacious materialism. One of Fitzgerald’s great achievements is to expose the ugly, predatory underside of what the dream had become under capitalism while preserving the beauty and promise of the original aspiration: to begin again and achieve perfection.

Living in Paris in 1925 brought Fitzgerald into the company of writers, artists, and intellectuals such as Gertrude Stein, Man Ray, Picasso, Jean Cocteau, and Erik Satie, who were casting off the old ideas and art forms and experimenting with new ones more indicative of life in the twentieth century. Fitzgerald’s French biographer, André LeVot, describes the attraction Paris held for Fitzgerald in this way:

Paris was then the capital of the imagination, the promised land of artists from all over the world … This was the place where all the world’s scattered and repressed aspirations converged and flowered … Except for Jazz, the arts were stagnating in the United States. The whole country had eyes only for Wall Street, where financial speculation had reached fever pitch.11

While living in France, Fitzgerald met Ernest Hemingway, generously championed his writing, and remained a loyal if uneasy friend over the years as Hemingway condescendingly played the role of superior big brother.12 If France first appeared to these expatriates to be paradise, Fitzgerald still sensed the clock was ominously ticking down the minutes to when it would be spoiled. He later wrote that “by 1928 Paris had grown suffocating” and that with “each new shipment of Americans spewed up by the boom the quality fell off, until towards the end there was something sinister about the crazy boatloads” (CU 20).

When the Fitzgeralds returned to America, Fitzgerald tried his hand at screenwriting in Hollywood, without success. The couple then moved to Delaware and rented an elegant old mansion, Ellerslie, which was rumored to be haunted. When guests arrived, Fitzgerald had stationed the butler out of sight with instructions to make ghostlike noises and rattle a chain. Meanwhile, he told everyone that it must be the ghost of Ellerslie. Fitzgerald enjoyed this stunt so much that one night when friends were sleeping over, he slipped into their bedroom with a sheet over his head and moaned until the husband awoke with start and took a swing at him. Suddenly, flames appeared. Fitzgerald, tipsy, had foolishly been smoking a cigarette under the sheet.13 Episodes like this made for good stories, but between parties, drinking, and arguments with Zelda, Fitzgerald made little progress on his next novel.

When the Fitzgeralds returned to France in 1929, Zelda devoted herself obsessively to ballet classes, suffered her first breakdown, and entered a hospital in Switzerland for treatment. Although Zelda’s parents never talked about it, there was a family history of mental illness.14 Zelda had always been impulsive, but by this time, it was clear that she was seriously ill. The year 1929 marked a crash for the Fitzgeralds as dramatic as the economic crash in America. Fitzgerald’s own health declined, earning a living became increasingly difficult, and he worried constantly about Zelda. He paid endless medical bills and, again, borrowed money against future work.

The Fitzgeralds left Europe for good in 1931. Zelda suffered another breakdown in 1932 and entered Johns Hopkins Hospital, and later Sheppard Pratt Hospital, in Baltimore. While in Hopkins, she hurriedly wrote an autobiographical novel, Save Me the Waltz (1932), based on her marriage, the same material that Fitzgerald was using in his novel in progress. Fitzgerald believed that its publication would greatly diminish the public’s response to his own. Moreover, he argued, he was the professional writer, and their living depended on his income. Fitzgerald hoped to reestablish his reputation with the new novel, Tender Is the Night (1934), a study of the American expatriate scene in France based on his own experience.15 But as Arthur Mizener suggests, Fitzgerald had even more than money and reputation at stake: Fitzgerald was desperately hoping that the novel’s reception would restore “his ability to believe in himself” (280). Critics, though generally positive, still expressed disappointment that the novel was not as good as they had anticipated, a judgment that has changed since Fitzgerald’s death, but one that had a disastrous effect on Fitzgerald at the time.

As Fitzgerald’s belief in himself spiraled downward, he tried to examine what had gone wrong in his life in a series of autobiographical essays for magazines. In “Sleeping and Waking” (1934), Fitzgerald writes candidly about his insomnia, which caused him to obsess over his least heroic moments and conclude this: “Waste and horror – what I might have been and done that is lost, spent, gone, dissipated, unrecapturable.” He writes about “night-cap[s]” and “luminol” (at the time a commonly prescribed barbiturate now known to be addictive and to exacerbate alcoholism), his “intense fatigue of mind,” and “the perverse alertness of [his] nervous system” (CU 66, 67). Fitzgerald’s advanced alcoholism resulted in the onset of rapid physical deterioration. He entered the hospital for treatment, but any small progress was soon blotted out by humiliating relapses. In 1935, Fitzgerald hit his lowest point and wrote the three essays in the “Crack-Up” sequence, published in Esquire in 1936. As the country was still in the Depression, it seemed appropriate to Fitzgerald to describe his own deterioration in economic metaphors. “I began to realize,” he wrote, “that for two years my life had been a drawing on resources that I did not possess, that I had been mortgaging myself physically and spiritually up to the hilt” (CU 72). As Mizener concludes, although “Fitzgerald’s crack-up was not so final as he supposed … he was a scared man whose success was of a very different order from what the man he had been before he went emotionally bankrupt had desired and, to a large matter achieved. For the rest of his life he continued to think of himself as living on what he had saved out of a spiritual forced sale” (291).

Fitzgerald returned to Hollywood in 1937 and, writing for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), he earned a steady salary, slowly repaid his debts, and provided for Zelda’s care while she lived intermittently between her mother’s home in Montgomery and Highland Hospital in North Carolina, to which she returned during periods of relapse. Zelda was never well enough to join Fitzgerald in Hollywood. They stayed in touch, sharing each other’s daily lives through letters, not knowing that they would never live together again. While living alone in Hollywood, Fitzgerald fell in love with Sheilah Graham, who, along with his secretary, Frances Kroll, had a steadying influence on his life. Graham would later write a loving memoir about their time together, saying that during the last year of his life he did not drink, his morale was high, and he was absorbed in writing another novel.16 By that time, however, alcoholism had done its damage. On December 21, 1940, Fitzgerald suffered a sudden and fatal heart attack at the age of forty-four. Zelda was too ill to attend the funeral. Eight years later, at midnight on March 10, 1948, Highland Hospital caught fire, and Zelda perished in the flames. Scott and Zelda are buried together in St. Mary’s Catholic Church cemetery in Rockville, Maryland. Neither of them had lived to see fifty.

During Fitzgerald’s final years in Hollywood, he understood that he was a forgotten man, but he nonetheless died fully engaged in and optimistic about his writing. “I’m deep in the novel,” he wrote to Zelda two months before his death, “living in it, and it makes me happy … Two thousand words today and all good” (S&Z 373). Published posthumously, The Last Tycoon (1941), even in its incomplete form, is still considered one the best fictional treatments of Hollywood. The themes of Fitzgerald’s final novel – love, aspiration, the conflict between American ideas and American life – are consistent with his previous work. But Fitzgerald was an artist whose work never fell into safe patterns of repetition. As he experienced new situations, he tried new things in his fiction. The Last Tycoon retains Fitzgerald’s characteristic verbal sparkle while it also reveals a more deeply mature point of view and a writer in control of his art.

The Fitzgerald legend – that he was a casualty of the Jazz Age, a playboy who threw away a fortune and drank away his talent – has given unsympathetic biographers grist for biographies that emphasize the worst aspects of Fitzgerald’s life with less than judicious accuracy.17 Bruccoli has corrected the part of the legend that damaged his reputation with painstaking documentary evidence of Fitzgerald’s conscientious attention to craftsmanship. The fact that Fitzgerald has for decades now been a writer whose work continues to speak to new readers and aspiring writers like few other voices attests to the depth and authenticity of the work itself, independent of the legend. Paul Auster, for example, is only one of the writers who have acknowledged the profound power Fitzgerald’s work has had in his own life:

I first read The Great Gatsby as a high school student more than thirty years ago, and even now I don’t think I have fully recovered from the experience … it cuts to the heart of storytelling itself – and the result is a work of such simplicity, power, and beauty that one is marked by it forever. I realize that I am not alone in my opinion, but I can’t think of another twentieth-century American novel that has meant as much to me.18

Many readers from all over the globe might say nearly the same thing. Fitzgerald’s fiction has a way of becoming personal: His readers recognize the sense of infinite longing even while at the same time they internalize his cautionary voice. In Fitzgerald’s world, to desire and to imagine are as close to greatness as one will ever get. History, individual and collective, is the story of dreams made material and thereby corrupted.

Although Fitzgerald’s reputation as a writer has been restored, two additional correctives to the legend are still needed. First, the role alcoholism played in his life is still sometimes used as an excuse either to dismiss Fitzgerald as a drunk or to romanticize his drinking. Alcoholism is a complicated and devastating disease, and Fitzgerald lived and wrote in a state of extreme physical and emotional discomfort brought on by an illness almost no one understood or sympathized with, including himself. Fitzgerald channeled his experience into his fiction. His characters are drawn to alcohol even as it destroys them: The material world once again, alcohol in this case, first intensifies the imagination, then corrupts it. The fact that alcoholism is a disease makes the role it plays in human history and life no less real and no less a significant and moving subject for fiction. Everything Fitzgerald experienced and felt as a result of his drinking went into his work and is part of what makes that work important and lasting.19

Another important corrective to the legend, which over the past decades has understandably emphasized the tragic elements of Fitzgerald’s life, is to remember that he also enjoyed much of his life. Exuberance characterized his personality as much as melancholy: He loved pranks and was quick to laugh, his friendships tended to be heartfelt and lifelong, and he was doggedly true to his vaulting ambition to become a first-rate writer. He had the satisfaction of knowing that at his best he had been a great one. Yet Fitzgerald could still laugh at himself. His college friend Edmund Wilson, for example, tells a story about Fitzgerald overhearing some of his friends making fun of a “bathetic” passage in an early version of The Beautiful and Damned: “But … he had not really seen Anthony. For Maury had indulged his appetite for alcoholic beverage once too often: he was now stone-blind!” According to Wilson, Fitzgerald, who had been entirely serious when he wrote the passage, laughed as hard as anyone and improvised an even worse Fitzgeraldian passage on the spot: “It seemed to Anthony that Maury’s eyes had a fixed stare, his legs moved stiffly as he walked and when he spoke his voice was lifeless. When Anthony came nearer, he saw that Maury was dead.”20

In addition to humor, Fitzgerald also had a gift for friendship. Frances Kroll Ring writes in her memoir of Fitzgerald’s last year that when he died, his daughter, Scottie, wrote asking her to set something in his possession aside for Margaret Turnbull. “[M]aybe just a pencil,” Scottie suggested. Ring remembers that she “was struck by the trail of warmth Scott left behind so that a memento – even a pencil – would have such sentimental value for a friend.”21 Fitzgerald’s life and fiction are indisputably tragic, but they also convey an all-too-often-missed sense of honor and a spirit of generosity and goodwill. What Fitzgerald once said was America’s defining characteristic – “a willingness of heart”22 – was ultimately his own.

Notes

1 Although Fitzgerald never wrote an autobiography, he kept meticulous personal records in a variety of forms over the course of his life: The Thoughtbook of Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald, , ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Library, 1965) reproduces Fitzgerald’s account of his social life, romances, and popularity when he was fourteen; F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Ledger, intro. by (Washington: Bruccoli Clark/NCR, 1973) is a facsimile of the ledger in which Fitzgerald recorded summary notes for each year of his life to 1937, along with a complete list of his works, and a year-by-year list of his earnings; The Romantic Egoists: A Pictorial Autobiography from the Scrapbooks and Albums of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, M. J. Bruccoli, S. F. Smith, and J. P. Kerr, eds. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, Reference Bruccoli, Smith and Kerr1974), is an invaluable compilation of the baby books, scrapbooks, photographs, reviews, letters, and other memorabilia the Fitzgeralds preserved to document their lives; The Notebooks of F. Scott Fitzgerald, , ed. (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich/Bruccoli Clark, 1978), contains fragments of conversations, quips, observations and descriptions he might use in his writing, along with brief of notes of self-analysis. In addition, the personal essays Fitzgerald wrote between 1931 and 1937, collected in The Crack-Up, , ed. (New York: New Directions, 1945), are, as Wilson claims, “an autobiographical sequence which vividly puts on record his state of mind and his point of view during the later years of his life” (11). As chapter 3 in this volume suggests, Fitzgerald was also a tireless writer of letters.

2 , A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald: Fool for Love (New York: Congdon & Weed, 1983), x. Subsequent references to this biography are included in the text.

3 A. Turnbull, Scott Fitzgerald (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, Reference Turnbull1962), 17. Subsequent references to this work are included in the text.

4 , The Far Side of Paradise (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965), 3. Subsequent references to this biography are cited parenthetically in the text.

5 , “Author’s House,” Afternoon of an Author, , ed. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1958), 185.

6 In “Sleeping and Waking” (1934), The Crack-Up, , ed. (New York: New Directions, 1945), Fitzgerald writes that his daydream of heroically winning a football game for Princeton against Yale has finally “worn thin” (66).

7 Reproduced in The Romantic Egoists: A Pictorial Autobiography from the Scrapbooks and Albums of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, , , and , eds. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1974), 6.

8 M. J. Bruccoli, Some Sort of Epic Grandeur: The Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald, 2nd rev. edn. (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, Reference Bruccoli and Baughman2004), 46. Subsequent references to this biography are included in the text.

9 See III, The Perfect Hour: The Romance of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ginevra King, His First Love (New York: Random House, 2006) for an account of this relationship and for letters Ginevra King wrote to Fitzgerald.

10 For a discussion of the role short stories played in Fitzgerald’s life and work, see B. Mangum, A Fortune Yet: Money in the Art of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Short Stories (New York: Garland, Reference Mangum1991).

11 , F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Biography (New York: Doubleday, 1983), 185.

12 For full discussions of their relationship, see , Scott and Ernest: The Authority of Failure and the Authority of Success (New York: Random House, 1978) and Fitzgerald and Hemingway: A Dangerous Friendship (New York: Carroll & Graff, 1994); also S. Donaldson, Hemingway and Fitzgerald: The Rise and Fall of a Literary Friendship (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, Reference Donaldson1999).

13 , “A Weekend at Ellerslie,” The Shores of Light: A Literary Chronicle of the 1920s and 1930s (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1985), 383.

14 In Epic Grandeur, Bruccoli writes that Zelda’s maternal grandmother committed suicide (93), her father “suffered a nervous breakdown” (92–93), her sister Marjorie “was subject to nervous illness most of her life” (91), and her brother, Anthony, committed suicide in 1933 (296).

15 See , F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Critical Portrait (New York: Holt, 1965). Piper contends that the pair of novels depicts the Fitzgeralds’ different viewpoints of their marriage and that “the disturbing thing about both novels is their authors’ mutual failure to comprehend the other’s point of view” (192, 204).

16 S. Graham and G. Frank, Beloved Infidel (New York: Holt, Reference Graham and Frank1958), 311.

17 , for example, in his preface to Invented Lives: F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald (1984), admits his antipathy toward his subjects and states his intention “not to let the glamorous Fitzgeralds get away with anything” (xvii). J. Myers seems determined to depict Fitzgerald in the worst possible light in his biography Scott Fitzgerald (1994). in Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in Paradise (2002) pursues a line of tawdry speculation into the Fitzgeralds’ sex lives.

18 Qtd. in , F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby”: A Literary Reference (New York: Carroll & Graff Publishers, 2000), 308.

19 For the role that alcohol and alcoholism have played in American history and in the 1920s in particular, see , Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2011) and Prohibition, dir. K. Burns and L. Novak (Walpole, NH: Florentine Films, 2011), DVD.

20 , “F. Scott Fitzgerald,” The Shores of Light: A Literary Chronicle of the 1920s and 1930s (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1985), 33.

21 , Against the Current: As I Remember F. Scott Fitzgerald (San Francisco: Ellis/Creative Arts, 1985), 128.

22 “The Swimmers” [1929] in , ed., The Short Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1989), 512.