Book contents

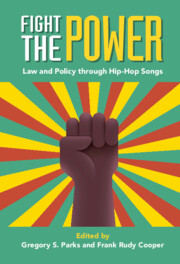

- Fight the Power

- Fight the Power

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Still Fighting the Power

- Part I Policing

- Part II Imprisonment

- Part III Genders

- 8 Roxanne Shanté’s “Independent Woman”: Making Space for Women in Hip-Hop

- 9 From the 1930s to the 2020s: What Ice Cube’s Song “Endangered Species” Meant for Four Generations of Black Males

- 10 The Master’s Tools Will Not Dismantle the Master’s House: Hip-Hop, Young M.A., and Gender Norms

- Part IV Protests

- Index

9 - From the 1930s to the 2020s: What Ice Cube’s Song “Endangered Species” Meant for Four Generations of Black Males

from Part III - Genders

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 January 2022

- Fight the Power

- Fight the Power

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Still Fighting the Power

- Part I Policing

- Part II Imprisonment

- Part III Genders

- 8 Roxanne Shanté’s “Independent Woman”: Making Space for Women in Hip-Hop

- 9 From the 1930s to the 2020s: What Ice Cube’s Song “Endangered Species” Meant for Four Generations of Black Males

- 10 The Master’s Tools Will Not Dismantle the Master’s House: Hip-Hop, Young M.A., and Gender Norms

- Part IV Protests

- Index

Summary

Robert Pervine and colleagues employ Ice Cube’s 1990 song, “Endangered Species” to explicate the popular narrative on black men as an endangered species. This song was preceded by seven-years by Walter Leavy’s 1983 article in Ebony Magazine. Leavy introduced the black community to the provocative question, “Is the black male an endangered species?” To emphasize the deteriorating condition of the African American male, Leavy pointed to a number of factors including high rates of unemployment, homicide, and imprisonment, as well as a decrease in life expectancy that negatively impact their ability to prosper in life. The term “endangered species” refers to a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular area. Causes of the endangerment are usually the loss of habitats, poaching, and the unleashing of an invasive species, in this case police violence. The concept of black males as an endangered species was a reversal of the newly created sense in the US coming out of the 1950s and 1960s that America needed to improve the conditions of the Black Community in order to make good on its commitment to abolish the basic injustice of segregation.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Fight the PowerLaw and Policy through Hip-Hop Songs, pp. 187 - 206Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022