During her thirty years in Şarköy, a quaint beach town about a four-hour drive west of Istanbul, an elderly lady named Gül, whose petite, five-foot frame can barely contain her exuberant personality, earned herself quite a reputation among her neighbors. When I visited her in 2014 and again in 2016, “Auntie Gül” or “Gül Teyze” (as neighbors called her deferentially) spoke loudly and excitedly, switching back and forth between Turkish and German. For vacationers and passersby, Gül’s bursts of German must have seemed inconsonant with the picturesque local setting of Şarköy, which has remained untainted by the booming international tourism industry so evident elsewhere along the Turkish coast. Long-term residents, however, were accustomed to Gül’s frequent use of German, and truth be told she was not the only local who did not quite fit in. In fact, within just a three-mile radius lived two dozen other so-called Almancı, as Turkish migrants in Germany and Western Europe are called derogatorily in Turkish. Like Gül, they too had returned to Şarköy only to become the targets of local gossip and speculation. Depending on whom I asked, these returnees were simultaneously outsiders and insiders, embraced and ostracized. They were both Turkish and German, neither Turkish nor German, or perhaps half-and-half.

Gül and the other returning migrants in Şarköy are just some of the millions of people who have journeyed back and forth between Turkey and Germany for the past sixty years, fundamentally reshaping both countries’ politics, economics, cultures, and national identities in the process. Since the 1970s, Turks, 99 percent of whom are Muslim, have been Germany’s largest and most contentious ethnic minority. Despite Germany’s historical refusal to identify as a “country of immigration” (Einwanderungsland), the reality is undeniable: today, people with Turkish heritage in Germany number at nearly 3 million, representing approximately 12 percent of the 23.8 million “people with migration backgrounds” (Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund) in a country where every fourth person is now ethnically “non-German.”Footnote 1 Migration is also crucial to Turkey, not only in terms of the diaspora. Four million people living in Turkey are ethnic Turks who at some point remigrated after living in Germany. No longer can one speak only of a Turkish diaspora in Germany without considering what one might call a “German diaspora” in Turkey, comprised of return migrants.Footnote 2

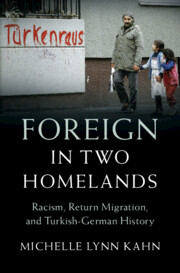

The eldest among these returnees, like Gül, now in their eighties, had been part of the first generation of Turks to migrate abroad as participants in West Germany and Turkey’s bilateral guest worker program (Gastarbeiterprogramm), which lasted formally from 1961 to 1973. As young men and women, they had learned that the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) suffered from a labor shortage and was recruiting foreign workers to revitalize its industry after the death and destruction of the National Socialist regime, World War II, and the Holocaust. They had also heard the plea from the Turkish government, which faced the opposite problem: too many workers and not enough jobs. Their backbreaking labor in German factories and mines would be a patriotic duty, the Turkish government insisted, as the workers would return with newfound technical knowledge and skills to spark their struggling homeland’s internal industrialization.Footnote 3 For the migrants themselves, the goal was overwhelmingly financial. Racked by poverty and unemployment in Turkey, they believed that working in Germany would allow them to earn riches beyond their wildest dreams, secure a better life for their families, and retire comfortably upon their return (Figure I.1).Footnote 4

Figure I.1 Gül, age twenty-eight, waves the Turkish flag on a train from Istanbul to Göppingen, where she worked as a guest worker, mid-1960s.

At first, Gül felt welcome in the Federal Republic, and that feeling remained with her for quite some time. By the early 1980s, however, she watched in horror as Turks became the primary targets of West German racism since the Holocaust. Amid the global economic recession and unemployment following the OPEC oil crisis of 1973, West Germans argued that guest workers had overstayed their welcome. In response, the West German government stopped recruiting guest workers in 1973 and encouraged existing guest workers to leave. Fearing further restrictions, however, guest workers navigated the situation by exploiting West Germany’s lax family reunification policy (Familiennachzug) and bringing their spouses and children to the Federal Republic.Footnote 5 On the streets, neo-Nazis and right-wing extremists shouted “Turks out!” (Türken raus!), spray-painted swastikas and racist graffiti, and attacked migrants – sometimes fatally. Inside parliamentary chambers, politicians responded to popular racism by passing a law to persuade Turks to leave the country – or, as critics decried, to “kick out” the Turks. Based both on culture and biology, this racism was overlaid onto an archaic ethnoracial definition of citizenship that dated back to 1913. Rather than embracing guest workers’ contributions to West Germany’s famed “economic miracle” (Wirtschaftswunder), Germans blamed them for taking their jobs, perpetrating crimes, birthing too many babies, draining the social welfare system, and lowering the quality of German schools. They further justified their racism with an essentialist, Orientalist interpretation of Turkish migrants’ culture and Islam that denigrated the migrants as “backward,” “authoritarian,” and “patriarchal.”Footnote 6 The overall conclusion, many Germans insisted, was clear: Turks could never integrate into German society, and they could never truly be considered German.

It was amid this racist climate of the 1980s that hundreds of thousands of migrants like Gül left West Germany and returned to cities, towns, and villages throughout Turkey. Gül and the others who chose to settle in Şarköy did so deliberately, hoping to live out their twilight years as they pleased: drinking tea, chatting with neighbors, and lounging along the sapphire-blue Marmara Sea. Underlying their triumphant return, however, was a sense of unease. The foreignness that they experienced in Germany accompanied them back to Turkey – this time, in the eyes of their Turkish neighbors who had not migrated. Both to their faces and behind their backs, neighbors mocked them as nouveau-riche, culturally estranged, and no longer “fully Turkish.” They insisted that the migrants had transformed into Almancı – the derogatory moniker that I translate as “Germanized Turk.” For the home country, the problem was not that the migrants had insufficiently integrated into German society, but rather that they had excessively integrated into it.

For the migrants themselves, the term Almancı is a slur. Many regard it as the Turkish analog of Ausländer, the German word for foreigner, which is frequently deployed to derogatory effect. This sentiment is best encapsulated in the rhyming phrase “Almanya’da Yabancı, Türkiye’de Almancı” (Foreigner in Germany, Almancı in Turkey), which is the title of a 1995 anthology of essays and poems by migrants.Footnote 7 The cartoon on the book’s cover conveys the message well (Figure I.2). A stereotypically portrayed guest worker – a man with working boots, a mustache, and a feathered fedora – stands between two signs pointing in opposite directions to “Deutschland” and “Türkei” and carries a red bindle adorned with the Turkish half-moon. On his buttocks is a footprint in the colors of the German flag, symbolizing that Germans have not only kicked him out of the country in response to rising racism but also that his time spent in Germany has left an indelible imprint on him that he can never erase.Footnote 8 But crucially, returning to Turkey is not a positive experience. His shoulders are hunched, his expression is somber, and tears stream down his face. As the anthology’s writings convey, being labeled as an Almancı makes the migrants feel foreign even in their own homeland.

Figure I.2 Cartoon on the cover of the 1995 anthology Almanya’da Yabancı, Türkiye’de Almancı (Foreigner in Germany, Almancı in Turkey), illustrating the migrants’ dual estrangement.

Of all the so-called Almancı in Şarköy, Gül stood out the most. She had even earned a special nickname: “The Woman with the German House.” Apparently, as her neighbors told me, Gül loved Germany so much that she had attempted to transport her entire German life to Turkey when she moved back in the 1980s. Jaws open and ears abuzz, neighbors had gawked at Gül and her late husband’s red station wagon, a German Volkswagen Passat, filled to the brim with construction materials lugged 3,000 kilometers from Germany. Everything in her two-story home – the appliances, light switches, doors, and windows – had been “Made in Germany.” Gül confirmed the rumors. While giving me a tour, she pointed out German pots and pans, bedroom furniture, picture frames, vases, radios, televisions, and chandeliers. In her kitchen, she even had a German deli meat slicer, which, she whispered shamefully, she had often used to slice ham. “I miss pork!” she exclaimed and lamented having to keep her “yearning for beer and bratwurst” a secret.Footnote 9 If neighbors found out that she was violating Muslim dietary restrictions, they might call her not only an Almancı but also a gâvur, a derogatory word for non-Muslims.

Well aware that her private home had become the target of local gossip, Gül defended herself by dismissing her German possessions as “just things.” To any outside observer, however, these objects clearly had emotional significance. Her middle-aged nephew, who accompanied us on the tour and had been threatening to clean the junk out of her house for years, likewise saw through Gül’s attempts to distance herself from the term Almancı. “She doesn’t know what she’s talking about,” he said, rolling his eyes. “Obviously she’s obsessed with Germany, and she keeps these things around so that she never loses the connection.”Footnote 10 His assessment rang true. Weary of travel in her old age, Gül had been visiting Germany less frequently. She had given up her German apartment, where she had often spent up to six months at a time, and now traveled there only once a year to visit her sister. Holding onto these objects and continuing to speak German helped preserve her emotional ties to the beloved “second homeland” that her body had long departed. Neither in her reputation nor her heart, could she escape her connection to Germany (Figure I.3).

Figure I.3 Gül, then in her early 80s, welcomed the author in her “German house,” 2016. In the background is one of Gül’s most cherished possessions from Germany: a red radio. Author’s personal collection.

Although each of the returning migrants in Şarköy had a different relationship to their Almancı identity, the pattern was the same for all – the label had been initially imposed upon them externally by individuals within Turkish society, by fellow Turks who had never been to Germany and had little direct knowledge of what life in Germany was like. Nevertheless, the nonmigrants were still able to judge from afar whom and what could be considered “German.” Little by little, year after year, as guest workers like Gül returned to Turkey driving German cars, wearing German clothes, giving neighbors tastes of German chocolates, speaking German, and raising German-speaking children, Turks in their home country increasingly concluded that they had transgressed their national identity. Neither fully Turkish nor fully German to outside eyes, the migrants existed in a liminal space between rigidly constructed conceptions of Turkish and German national belonging that had come to assume new and contested undertones of fluidity. As physical estrangement evolved into emotional estrangement, the migrants became foreign in two homelands.

Return Migration and Transnational Lives

This book tells the history of Turkish-German guest worker migration from a transnational perspective, focusing on the themes of return migration, German racism, and the migrants’ changing relationship to their home country. It begins in 1961, when Turks first arrived in West Germany as formally recruited “guest workers” (Gastarbeiter), and ends in 1990, the year that marked both the reunification of divided Germany and landmark revisions to German citizenship law.Footnote 11 Putting a human face on migration, it tells the stories of guest workers and their families as they traveled back and forth between Germany and Turkey and navigated their uncomfortable connections to both countries over three decades. In so doing, it turns the concept of “integration” on its head: while not nearly as egregious as the overt racism they faced in Germany, many migrants encountered parallel difficulties reintegrating into their own homeland. After years or decades of separation, their friends, neighbors, and relatives met them not only with open arms, but also with ostracization, scorn, and disavowal. Turkey’s ambivalence toward returning migrants complicates our understanding of German identity. As much as Germans assailed Turks’ alleged inability to integrate, they had integrated enough for their own countrymen to criticize them as culturally estranged, “Germanized,” and no longer “fully Turkish.” Kicked out of West Germany and estranged from Turkey, many migrants felt foreign in both countries, with consequences that still drive a rift between Germany, Turkey, and the diaspora today.

By focusing not only on the migrants’ arrival and integration but also on their return and reintegration, this book adds complexity to a story that has been typically told within German borders. Its narrative is – at once – German, Turkish, European, transnational, and local. The chapters resemble the migrants’ lives in that none is strictly delineated by the rigid boundaries of a static “homeland” or “host country.” Likewise, none offers an exclusively “German” or exclusively “Turkish” perspective. Rather, the book and its various chapters take readers on a spatial journey, following the migrants back and forth between West Germany and Turkey, as well as along the 3,000-kilometer international highway that lay between them, traversing Austria, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria at the height of the Cold War. Zooming in and out between domestic policies, international affairs, public discourses, and the history of everyday life (Alltagsgeschichte), the story not only plays out in editorial offices, parliamentary chambers, and other public spaces, but also in more private settings where the migrants’ personal agency and emotions take center stage.Footnote 12 To portray the richness of the migrants’ transnational lives, the book brings together a kaleidoscope of sources collected in both countries and both languages, including government documents, newspaper articles, sociological studies, company records, handwritten letters, memoirs, films, novels, poems, songs, material objects, and two dozen oral history interviews that I conducted with former guest workers and their children.

Above all, this book rests on a fundamental premise: global migration and mobility are central to the history of modern Europe, and we cannot fully understand European history without placing migrants’ transnational lives at the center of it.Footnote 13 To a certain extent, this premise might seem intuitive: after all, migration and mobility are core parts of human experiences across time and space. But placing migration at the center of European history is especially crucial, not least since Europeans have historically defined their national identities homogenously. While all European societies have struggled to come to terms with demographic shifts, the German experience has been peculiar due to the country’s exclusive, ethnonationalist, and blood-based (jus sanguinis) definition of identity, which began to change only in the 1990s.Footnote 14 Such a narrow view of what it means to be “European,” or what it means to be “German,” obscures the reality that people in Europe have always been on the move. Europeans have traveled both within and beyond the constructed borders of empires, nation-states, and supranational institutions, crossing landscapes and waterways near and far, and have often become immigrants themselves. Sometimes, such as during the ages of exploration and imperialism, they have twisted their outward mobility toward bloody and genocidal ends.Footnote 15 On the other hand, people from across the globe have traveled to Europe, increasingly settling there permanently. And in so doing, they have forever staked a claim as a part of European history, fundamentally reshaping both national and European identities.

Migration is not, however, always a one-directional process, whereby migrants leave a static “home country,” arrive in a static “host country,” and stay put. Rather, as scholars of transit migration have emphasized, migration is also circular and back and forth, marked by frequent twists, turns, and returns in “zigzag-like patterns” rather than straight lines.Footnote 16 Both temporarily and permanently, migrants often return to the places from which they came, encountering new and unexpected challenges while reintegrating.Footnote 17 Before they arrive at an intended destination, they pass through multiple cities, countries, landscapes, seascapes, and airways. And they often go on to further journeys, some planned and some unexpected, turning former destinations into mere stops along the way. Just as migrants impact their points of departure and arrival, so, too, do they shape the spatial buffer zones that they pass through.Footnote 18 In this sense, the journeys themselves, not just the start or end points, are central to migrants’ experiences, for they are the roads – both physical and psychological – on which migration happens. But, as the dark global history of slavery, imperialism, war, genocide, and displacement reminds us, their pathways are often precarious and involuntary. The policing of borders, whether through legislation, brutal force, or racial and socioeconomic exclusion, blurs the line between “voluntary” and “forced.”Footnote 19 These themes – return migration, the policing of borders, and the journey itself – guide this book.

Within this vast history of mobility and migration, the period after the end of World War II stands out for the enormous challenge – and opportunity – that the unprecedented rise in mass migration posed to European demographics and national identities. Although Europeans had previously encountered so-called foreigners within their borders, postwar labor shortages and decolonization brought millions of migrants to European shores – in numbers like never before.Footnote 20 Countries with long histories of brutal imperialism, like the United Kingdom and France, relied on migrants from their former colonies to revitalize their infrastructure.Footnote 21 The two halves of Cold War Germany, whose colonies had been stripped from them after World War I, sought laborers elsewhere.Footnote 22 Amid its 1955–1973 “guest worker” program, West Germany recruited workers from Italy beginning in 1955, Spain and Greece in 1960, Turkey in 1961, Morocco in 1963, Portugal in 1964, Tunisia in 1965, and Yugoslavia in 1968. Turkey, eager to export surplus laborers, sent workers to other countries as well: to Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands in 1964, France in 1965, Sweden and Australia in 1967, Switzerland in 1971, Denmark in 1973, and Norway in 1981.Footnote 23 The history of labor migration is also inextricable from the history of Germany’s Cold War division. Across the Iron Curtain, the German Democratic Republic (GDR), or East Germany, recruited “contract workers” (Vertragsarbeiter) from the socialist, communist, or nonaligned countries of North Vietnam, Cuba, Angola, and Mozambique.Footnote 24 And crucially, West Germany signed the 1961 recruitment agreement with Turkey just two months after the GDR began constructing the Berlin Wall, thereby cutting off the steady stream of East German day laborers. Highlighting the West German case is important because, as Emmanuel Comte has argued, the Federal Republic developed a “strategic hegemony” over European migration policy and European integration, shaping them in a way that favored its long-term geopolitical and economic interests.Footnote 25

Return migration was embedded into the logic of the Turkish-German guest worker program, but both the perceptions and reality of return fluctuated greatly from 1961 to 1990. Despite rampant discrimination even in the 1960s, West Germans initially welcomed guest workers as crucial to the economy.Footnote 26 This idea manifested in the choice of the problematic term “guest worker” itself, whose hospitable connotation distanced it from forced labor (Zwangsarbeit) under Nazism.Footnote 27 Also embedded in the word “guest” was the assumption that the migrants’ stays would be temporary. Per the recruitment agreement’s “rotation principle” (Rotationsprinzip), they were only supposed to stay for two years, after which time they would be rotated out and replaced by new workers. The Turkish government, too, initially welcomed the guest workers’ return on the grounds that they would bring the knowledge and skills needed to modernize their home country’s struggling economy. In reality, the rotation principle was minimally heeded, since guest workers wished to keep earning money in Germany, and employers considered it too cumbersome to train new workers. Beyond economics, political optics also played an important role in West Germany’s failure to adhere to the rotation principle: just decades after the atrocities of Nazism, forcibly moving labor migrants, as Adolf Hitler had done earlier in the twentieth century, was simply not an option.Footnote 28 Numerically, the turning point was the 1973 recruitment stop, after which half a million guest workers – 20 percent – left West Germany within three years.Footnote 29 Still, the number of Turkish citizens who left was outweighed by those who arrived through family migration in the 1970s.

By the early 1980s, the very idea that Turks had failed – or even refused – to go home became a dangerous weapon in Germans’ racist arsenal: if only Turks had returned as planned, many Germans insisted, these massive demographic changes and the perceived threat of Islam might have been avoided.Footnote 30 Such rhetoric feeds into what I call the “myth of non-return”: the idea that Turks’ return migration was a mere “illusion” or “unrealized dream” that failed to materialize. Because of its prevalence, this myth has influenced the writing of history.Footnote 31 Historians have generally treated Turkish-German migration as a one-directional process, whereby the migrants left Turkey, arrived in Germany, and did not return. Early studies situated the guest worker program within the longer history of labor migration and Germans’ experiences with ethnic minorities.Footnote 32 Thanks to more recent histories by Karin Hunn, Rita Chin, Sarah Hackett, Brittany Lehman, Jennifer Miller, Sarah Thomsen Vierra, Lauren Stokes, and Stefan Zeppenfeld, we now know much about West German migration policies and changing attitudes toward Turkish migrants, how the tensions of integration played out on the ground, how migrants experienced their daily lives, and how they negotiated their belonging with nuanced attention to gender and generational divides.Footnote 33 Brian J. K. Miller and Brian Van Wyck have illuminated the Turkish government’s motivations and its role in shaping the migrants’ lives in Germany.Footnote 34 Overall, however, the Turkish and German sides of the story – at least within the discipline of history – have largely been viewed as separate rather than inextricably linked.Footnote 35

In this book, I bridge this divide by taking readers on a back-and-forth transnational journey between Turkey and Germany, revealing that Turkish-German migration history is far more vibrant and dynamic than typically told. The core argument is the following: return migration was not an illusion or an unrealized dream but rather a core component of all migrants’ lives, and Turkish-German migration was never a one-directional process, but rather a transnational process of reciprocal exchange that fundamentally reshaped both countries’ politics, societies, economies, and cultures. We cannot understand how the labor migration impacted Germany without understanding how it impacted Turkey. We cannot understand German migration policy without understanding Turkish policy and how the two were constituted mutually. And we cannot understand the migrants’ experiences integrating in Germany without understanding their experiences reintegrating in Turkey. By unifying these two histories, this book expands our definition of “Europe” to include Turkey, provides a fuller understanding of migrants’ lives, and shows how migration – and migrants themselves – transformed both countries.

Far from oppressed industrial cogs tethered to their workplaces and factory dormitories, guest workers and their families were highly mobile border crossers. They did not stay put in West Germany but rather returned both temporarily and permanently to Turkey. They took advantage of affordable sightseeing opportunities throughout Western Europe, and each year many vacationed back in Turkey, typically traveling there by car on a 3,000-kilometer international highway that traversed the Cold War border checkpoints of Austria, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria. Once they arrived, they reunited with friends, relatives, and neighbors, built houses, invested money in their homeland, and shared stories of life in Germany. Hundreds of thousands, moreover, packed their bags, relinquished their West German residence permits, and remigrated to Turkey permanently, making their long deferred “final return” (in Turkish kesin dönüş, and in German endgültige Rückkehr). Around 500,000 of the 867,000 Turkish citizens who migrated to Germany between 1961 and 1973 eventually returned as expected, as did tens of thousands more who arrived in the 1970s through family reunification.Footnote 36 Returning to Turkey, and their journeys of return, were just as important to guest workers and their families as their time in West Germany (Figure I.4).

Figure I.4 Vacationing guest workers wait at the Düsseldorf airport for their flight back to Istanbul, 1970.

Guest workers’ decisions to stay or leave were also shaped by pressures from above. Both countries’ governments were deeply invested – both metaphorically and financially – in the question of the migrants’ return. Crucially, however, their goals differed: whereas West Germany strove to promote the migrants’ return, Turkey strove to prevent it. Racked by skyrocketing unemployment, hyperinflation, and foreign debt in the 1970s, the Turkish government changed its previously enthusiastic stance toward return migration, fearing that a mass return of guest workers would overburden the labor market and cut off the stream of remittance payments. Bilateral tensions climaxed when West Germany passed a controversial 1983 law that paid guest workers and their family members to leave immediately. The result of this law, which critics in both countries decried as a blatant attempt to “kick out the Turks” and “violate their human rights,” was one of the largest and fastest remigrations in modern European history. In 1984, within just ten months, 15 percent of the Turkish migrant population – 250,000 men, women, and children – packed their bags, crammed into cars and airplanes, and journeyed across Cold War Europe back to Turkey, with their residence permits stamped “invalid” at the border.

Crucial to this transnational story is the fraught, elusive, and highly politicized concept of “integration.” Beginning in the mid-1970s, Germans used “integration” (Integration or Eingliederung) to describe a linear process by which migrants should become part of German society by abandoning the features that make them different.Footnote 37 All three major political parties distinguished “integration” from another loaded term – “assimilation” (Assimilation) – on the grounds that the latter could slip into “forced Germanization” (Zwangsgermanisierung), a term that recalled the Nazis’ brutal “Germanization” of 200,000 Polish children by ripping them from their homes and giving them to German families on the basis that they had blonde hair and blue eyes and were thus “racially valuable.”Footnote 38 By contrast, postwar Germans considered “integration” more palatable because, at least in theory, it implied a “give-or-take process” in which both the migrants and Germans shared responsibility.Footnote 39 In practice, however, the rhetoric of integration gave rise to the expectation of assimilation: Germans blamed Turks for not “integrating” rather than acknowledging that they had done little to “integrate” them.

Viewed in a transnational frame, debates about “integration” were also fundamentally tied to return migration and to Turkish expectations about the role of the migrants in relation to their home country. One of the German conservatives’ arguments against “Germanization” was that it would be detrimental to the migrants – and to West German efforts to kick them out – as it would erase their Turkish cultural identities and thereby impede them from “reintegrating” upon their return. And, in fact, that turned out to be the case. Turks in the home country, as this book reveals, invoked the language of “Germanization” to express their concerns about the opposite problem: excessive integration into West Germany and the loss of Turkish identity. The transnational history of return migration thus shows how the migrants were caught not only between two countries but also between two opposing sets of multifaceted, shifting, and unachievable expectations about who they were at their very core: how they were supposed to act, what clothes they were supposed to wear, how much money they were supposed to spend, whom they were supposed to have sex with, what their moral and religious values were supposed to be, and ultimately where they belonged.

Placing the migrants at the center of this story, this book highlights their agency as they navigated both countries’ attempts to police their mobility, define their identities, and embrace or exclude them over three decades. It also reveals, however, that the very act of returning “home” was not always the joyous occasion that they had dreamed of. Instead of enjoying a happy homecoming, many found themselves socially ostracized and economically worse off than they had been in West Germany. In this sense, physically traveling to Turkey was not always a return to a static homeland but rather a journey to a place that had transformed in their absence and from which, over years and decades, they had become gradually estranged. For them, the challenge became not only how to integrate into Germany but also how to reintegrate into Turkey.

Gradual Estrangement from “Home”

Focusing on return migration not only highlights the migrants’ agency but also shows how migration shaped the lives of ordinary people in Turkey. When we think of migration only in terms of the people on the move, we tend to overlook a crucial reality: for every guest worker who went to Germany, there were dozens of friends, neighbors, and family members who stayed behind in Turkey. Even though many of them would never set foot in Germany, individuals in the homeland also had a stake in the guest worker program. Placing their hopes and dreams in the guest workers’ hands, they sent them off with not only physical but also emotional baggage. The expectations were clear: work hard, send money home, keep in touch, and return quickly. But the reality was complicated. Migration fundamentally disrupted the lives of those left behind, from their day-to-day activities and financial security to their relationships with relatives near and far. Just as the migrants had to adjust to their new lives in Germany, so too did individuals in Turkey have to adjust to their absence. Rethinking migration from their point of view underscores the inescapable dualities. Arrival meant departure. Immigration meant emigration. Presence meant absence.

Part I of the book, “Separation Anxieties,” shows how, through the everyday act of repeatedly crossing the two countries’ borders, guest workers and their children transformed their home country and destabilized dominant understandings of German, Turkish, and European identities from the 1960s through the 1990s. During this period, migrants became targets and carriers of difference and ambivalence in Turkish understandings of identity, as both the migrants themselves and observers in Turkey struggled to rethink their relationship to their homeland (vatan) while they lived, at least temporarily, 3,000 kilometers away.Footnote 40 While most guest workers yearned to return to the vatan, their children born or raised in Germany frequently questioned whether the vatan was truly their homeland or rather just a faraway place they knew from their vacations and their parents’ stories. Although they always remained an extension of the nation, they gradually became estranged from it as the discomfort surrounding them grew.Footnote 41 And because migration was circular, marked by frequent returns to Turkey for both short and longer periods of time, the distinction between “migrants” and “nonmigrants” also blurred. All at once, a person could feel – and be treated as – both uprooted and left behind.

The history of Turkish migrants’ dual estrangement is in many respects the history of emotions.Footnote 42 Anger, sadness, fear, joy, envy – all of these are fundamental parts of the human story told in this book. Emotions are socially constructed and dynamic, changing over time in response to circumstances and expectations. Still, understanding the migrants’ emotions does not always require reading between the lines. Instead, migrants explicitly expressed their emotions in the countless sources they produced: oral histories, handwritten letters, poetry, folk songs, love ballads, memoirs, novels, films, interviews with journalists, and petitions to government officials. They did so not only to express themselves, but also to gain sympathy, effect change, and achieve certain strategic aims in the process. At times, they also performed their emotions, attempting to appear happier or sadder than they actually were.Footnote 43 One guest worker staged happy photographs to send to worried loved ones, even though she felt miserable and homesick. Another pretended to cry on the train to Germany just to fit in with her fellow passengers, even though she was delighted to leave Turkey. Moreover, observers in both countries leveraged the migrants’ emotions toward political goals. Lamenting the sorrow of guest workers’ children became an especially powerful tool for opponents of immigration restrictions to express their discontent – albeit in ways that sometimes inadvertently diminished the migrants’ agency and perpetuated discrimination. The migrants’ emotions, in this sense, became a tool for reinforcing uneven power dynamics.

Turkish guest workers and their children were not a homogenous population, even though both countries largely tended to treat them as such. Although guest workers overwhelmingly came from rural parts of Anatolia, most of the early migrants came from major cities such as Istanbul. While guest workers have been stereotyped as male, women accounted for 8 percent in 1961, tripling to 24 percent in 1975 – a statistic reflecting firms’ desire to employ women, whose smaller hands made them better suited for delicate piecework.Footnote 44 Women who migrated formally as guest workers had different experiences than those who migrated through family reunification, as did children who spent most of their lives in Turkey versus children born and raised primarily in West Germany. Nor was the guest worker population ethnically, religiously, or politically homogenous. While Turkish guest workers were primarily Sunni Muslim, they also included internal minorities such as Kurds, Alevis, and Armenians, all of whom suffered a long history of persecution under Ottoman and Turkish rule.Footnote 45 Labor migration also overlapped with other forms of migrations, since applying for the guest worker program became a pathway for political dissidents and ethnic minorities to flee Turkey.Footnote 46 After the 1980 military coup, as the Turkish government perpetrated rampant human rights violations, the demographics of West Germany’s Turkish population further transformed, leading to contestations among Turkish nationalists, Kurds, and leftists that played out on West German soil. By the early 1980s, the backlash against Kurdish asylum seekers amplified the existing criticism of Turkish guest workers, becoming another potent weapon in the arsenal of those who wanted to “kick out” the Turks.

Each time guest workers and their children journeyed back to Turkey, they encountered a “homeland” that was not static but rather ever-changing. With the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk sought to build a new identity for Turkey that was rooted in modernization and “Turkishness.” The 1924 constitution bestowed citizenship to individuals born in Turkey regardless of their religion and race if they embraced Turkish culture and language.Footnote 47 Yet the Kemalist utopia of a singular Turkish nation belied the reality that Turkey remained politically, socially, and culturally fragmented and racked by economic turmoil. During the period covered by this book, Turkey experienced three military coups: in 1960 (just one year before the first guest workers arrived in West Germany), 1971, and – most crucially for this book’s narrative – 1980. Struggling to position Turkey in the increasingly neoliberal global economy, policymakers found themselves in a virtually perpetual state of economic crisis that intensified amid the global recession of the 1970s. Especially central to the migrants’ experiences – and to transnational attitudes about them – was the continued social, economic, and cultural gap between Turkish cities and the countryside.Footnote 48

Rather than passively responding to these vast changes, guest workers and their children played active roles in accelerating them.Footnote 49 Alongside guest workers’ contributions to Turkey’s economy, society, culture, and identities, this book examines the historical process by which guest workers and their children introduced new categories of ambivalence and exclusion in Turkey. To anchor this analysis, the book traces the origins of the most contentious Turkish term for classifying the migrants: Almancı. Crucially, the term has not been used to describe all Turks living in Germany, a group that even before the 1960s included diplomats, students, and white-collar professionals. Rather, it initially emerged as a more particular reflection of Turkish ideas about guest workers, class, and socioeconomic difference. The economic connotations of the term, which does not translate smoothly into English, are evident in its etymology. Almancı combines the Turkish adjective Alman (German) with the suffix “-cı.” Most akin to the English “-er” or “-ist,” this suffix typically creates a noun identifying a person by their professional occupation or how they make a living (a basketball player is a basketbolcu, a taxi driver is a taksici, an antiques dealer is an antikacı).Footnote 50 By this logic, an Almancı is simply a person who makes a living out of Germany. But the meaning of the term – often interchanged with Almanyalı and Alamancı – is complex. Noting the term’s derogatory connotation, Ruth Mandel has defined it as “German-like,” while Susan Rottmann has interpreted it as “becoming a ‘professional German’ and thus faking or putting-on German-ness.”Footnote 51

In this book, I deliberately define Almancı as “Germanized Turk,” and I investigate from a historical perspective how the term and its associated stereotypes developed from 1961 to 1990. Given its derogatory connotation, I do not use the word when referring to the migrants, but rather place it in quotation marks when discussing the home country’s explicit or implied perceptions of them. Though contested in both countries, the word “Germanized” is more suitable for this book than “German-like” because it underscores Turks’ concerns at the time that the migrants were undergoing a process of gradual estrangement – that they were transforming, to a certain extent, from Turks into Germans.Footnote 52 The emphasis on the historical process of becoming an Almancı reflects the dual character of discourses surrounding the contentious concept of “integration.” Whereas West Germans complained about Turkish migrants’ insufficient integration, the Turkish government, media, and population worried about excessive integration – that long-term exposure to West Germany had estranged the migrants from Turkey, making them unable to reintegrate. In its most virulent uses, the term Almancı blamed the migrants for their own estrangement: not only had the migrants absorbed German culture through osmosis, but they had also made an active choice – a choice for Germany over Turkey, and a choice for abandoning those at home.

Whether out of hostility or jest, the term Almancı also projected Turks’ anxieties about the country’s external and internal transformations in a globalizing Cold War world, particularly regarding “Westernization” and urbanization. This point recalls Ayşe Kadıroğlu’s suggestion that “the Turkish psyche has been burdened with the difficult task of achieving a balance between the Western civilization and the Turkish culture.”Footnote 53 In this sense, when viewed in a geopolitical frame, concerns about the migrants’ “Germanization” and loss of Turkish identity reflected Turks’ broader ambivalence about their own country’s “Westernization,” “modernization,” and “Europeanization” during the 1960s through the 1980s.Footnote 54 But these tensions also reflected ambivalence about Turkey’s rural–urban divide, especially amid the internal seasonal labor migration that both preceded and overlapped with guest worker migration abroad.Footnote 55 When Turkish urbanites denigrated Almancı, they often recycled stereotypes about the rural labor migrants they encountered in Turkish cities, whom they – like Germans – disparaged as poor, backwards, and traditional. For villagers, by contrast, “Germanization” was a proxy for urbanization. Having already observed changes in the behaviors of seasonal migrants who returned from Turkish cities, villagers worried that migrants in West Germany would succumb to the seedy underbelly of urban life, drink alcohol, engage in sex and adultery, and abandon Islam.Footnote 56 As psychologist Gündüz Vassaf observed in his 1983 book on guest workers’ children, Turks’ previous experience with internal migration had already bred concerns that Anatolians were “Istanbulizing” (İstanbullarırken) and that Istanbulites were “Anatolianizing” (Anadolululaşıyor).

These separation anxieties, I argue, were inextricably linked to return migration, for it was during vacations and permanent remigration that guest workers reunited face-to-face with those in Turkey. Within the scope of transnational mobility, numerous crosscutting themes – at the levels of the family, community, and nation – all contributed to the development of the idea that the migrants had “Germanized” and become culturally estranged. Chapter 1, “Sex, Lies, and Abandoned Families,” traces the process of gradual estrangement in the migrants’ intimate and emotional lives, viewing them not as nameless, faceless proletarian workers but rather as spouses, parents, children, lovers, and friends. In the formal recruitment years of the 1960s and 1970s, guest workers tried to maintain close contact with their loved ones at home. Still, homesickness and fears of abandonment spread across borders. Amid West Germany’s sexual revolution, rumors about male guest workers having sex with buxom blonde German women, cheating on their wives, and abandoning their children spread like wildfire throughout Turkey, becoming core themes in Turkish media, films, and folkloric songs. Amid the rising family migration of the 1970s, guest workers’ children came to be seen in both countries as at once victims and threats. While Germans complained about migrant children as “illiterate in two languages,” Turks in the home country worried that they had excessively “Germanized.” These “Almancı children” (Almancı çocukları) were stereotyped as dressing and acting like Western Europeans, abandoning their Muslim faith, and barely speaking the Turkish language. Far more so than their parents, these children faced harsher social difficulties reintegrating into Turkey upon their return.

Ironically, the migrants’ growing emotional estrangement from their friends, neighbors, and relatives at home was largely attributable to the times when they physically reunited face-to-face. Chapter 2, “Vacations across Cold War Europe,” examines the significance of the seemingly mundane act of temporarily returning “home.” Every year, as a small seasonal remigration, guest workers embarked upon a three-day, 3,000-kilometer road trip from West Germany to Turkey, passing through Austria, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria at the height of the Cold War. Their unsavory experiences driving through Yugoslavia and Bulgaria reinforced their disdain for life east of the Iron Curtain and solidified their self-identification with the modernity and prosperity of Germany and “the West.” Moreover, the cars and consumer goods they brought from West Germany on their vacations played a significant role in external processes of identity formation. By the 1970s, those in the home country came to view guest workers as a nouveau-riche class of gaudy, superfluous spenders, or “little capitalists,” who neglected the financial needs of struggling local economies and had adopted the habit of conspicuous consumption – a trait that villagers associated with West Germany and Western Europe at the time.Footnote 57

Crucially, guest workers were one of the strongest backbones of the Turkish economy at a time of great economic crisis. Chapter 3, “Remittance Machines,” investigates how the growing rift between guest workers and their home country was tied up in the transnational circulation of finances amid an increasingly globalizing neoliberal economy. Government officials and journalists regularly referred to guest workers as “Turks working/living in Germany” (Almanya’da çalışan/yaşayan Türkler) and “our workers in Germany” (Almanya’daki isçimiz), the latter of which reflected the importance of guest workers’ economic contributions – not only to their own wallets but also to the entire nation. Each Turk working abroad, after all, was one less person to tally as unemployed. Likewise important were their remittance payments: cash transfers from West Germany to Turkey in Deutschmarks, a much more valuable currency than the hyperinflated Turkish lira. Guest workers sent remittances to their families on a regular basis, and tens of thousands invested in factories to be built in Turkey, often in their home regions. But, as this chapter reveals, Turkey’s dependence on – and cultural obsession with – guest workers’ Deutschmarks created a conflict between self and nation, especially regarding return migration.Footnote 58 The Turkish government was so desperate for remittance payments that it began to oppose the migrants’ return, even when it countered their best interests. Many migrants thus felt like “remittance machines,” unwanted not only in West Germany but also by their own government.

Although the Almancı label is primarily defined externally and used derogatorily, and largely based on stereotypes, the Turkish discourse about the migrants’ “Germanization” reveals an important point: whereas Germans have historically harbored anxieties about migrants’ inability to “integrate,” members of societies with high rates of outward migration, like Turkey, have developed fears of the opposite – and have responded with nationalist discourses according to which emigrants betray some or all of their identity by leaving their country of origin, choosing to remain abroad, and assimilating excessively. The very notion of “Germanization” casts migrants not as isolated “foreigners” (Ausländer), but as fundamentally German actors, exposing the reality that nineteenth-century notions of blood-based German citizenship no longer fit the dynamics of a migratory postwar world. In this way, the term “Germanization” itself suggests that Germans have not had a singular claim to delineating the contours of what it means to be German. Rather, both the Turkish migrants themselves and the populations of their home country, from the government and media to even the poorest of villagers, have been able to influence debates about German national belonging and the disputed role of Turkey in “Europe.”

Likewise, the idea of the Almancı encourages us to destabilize the directional categories we use to discuss migration. When they traveled back to Turkey for their so-called “permanent return,” they could be considered not as immigrants to but rather as emigrants from Germany. Although this interpretation falls shorter for guest workers and their children who were born in Turkey, it does apply to the experiences of thousands of children who were born or raised primarily abroad, and who knew Turkey only as a vacation destination or from their parents’ stories. One of my interview partners, Murad B., who was born in Germany, and whose parents shuttled him back and forth between the two countries before finally sending him to live with his grandparents in Istanbul, expressed this sentiment eloquently: “I think the term ‘going back’ to Turkey is so inappropriate, because I was never there to be back there … It’s not a ‘going back’ to somewhere. It’s a ‘going to’ somewhere that was completely strange.”Footnote 59

Racism and the History of 1980s West Germany

Part II of this book, “Kicking out the Turks,” writes the history of racism into the history of West Germany. Whereas the entire book spans 1961 to 1990, the second part focuses exclusively on the 1980s, a decade about which histories are still begging to be written. Thematically, Part II explores the nexus between return migration and what I call West Germany’s “racial reckoning” of the 1980s: a turning point at which Germans, Turkish migrants, and individuals in the migrants’ home country grappled, in both public and private, sometimes self-consciously, and sometimes not, with the very existence and nature of West German racism itself and especially the continuities between anti-Turkish racism and the Nazi past. This racial reckoning was motivated by a confluence of factors. As the demand “Turks out!” was amplified in the early 1980s, popular racism exploded with an intensity unprecedented in the Federal Republic’s history, second only to the surge in neo-Nazi violence in the early 1990s.Footnote 60 At precisely the same moment, West German intellectuals began publicly debating the role of the Third Reich and the Holocaust in German historiography and identity, sparking what became known as the “historians’ dispute” (Historikerstreit) of the 1980s.Footnote 61 As rising anti-Turkish racism was mapped onto the growing public attention to Holocaust memory, it became a tense part of Germans’ process of coming to terms with the past (Vergangenheitsbewältigung).

Racism is not static across time and space. Rather, the historian’s task is to examine how racism has manifested in different contexts – how racist discourses, targets of racism, and experiences of racism have evolved over time. For historians of postwar Germany, this task is especially challenging due to the prominence of the Holocaust in German understandings of racism. The emphasis on the singularity of the Holocaust, which was reaffirmed in the 1980s at the exact same time that Germans were debating how to kick out the Turks, inadvertently bolstered postwar Germans’ reluctance to acknowledge the varying forms of racism that have existed both before and after Hitler.Footnote 62 Moreover, the prominence of Holocaust education and memorial sites in Germany from the 1990s onward has made it easier to celebrate Germany as a success story when compared to other countries, particularly the United States, that have long repressed histories of imperialism, enslavement, and genocide.Footnote 63 But, as this book shows, the intensification of both state-sponsored and everyday racism in the 1980s, as well as the prevalence of overt Holocaust comparisons in public discourse, challenges the portrayal of the Federal Republic as a success story and questions the image of the 1980s as the decade during which West Germany stabilized, turned toward postnationalism, and acknowledged its collective guilt for the Holocaust.Footnote 64 West Germany was not only the liberal democratic precursor to reunified Germany in 1990; it was also a country of great darkness, fear, extremism, and racism, whose history could have turned out quite differently (Figure I.5).

Figure I.5 A West German neo-Nazi performs the Hitler salute, 1987. His shirt depicts Hitler and a swastika with the accompanying English-language text: “No remorse” and “The world will know Hitler was right.”

Engaging further with the history of emotions, this book shows how both racism and migrants’ experiences of racism were both fundamentally connected to fears of the future and memories of the past. Its interpretation thus reinforces Frank Biess’s and Monica Black’s respective conclusions that West Germany was riddled with “German Angst,” during which the “ghosts of the past” conjured existential fears about the stability of democracy itself.Footnote 65 As Biess explains, the key questions here are not only “how did West Germans make sense of the past?” but also “how did West German memories of their past inform anticipations of the future?”Footnote 66 Amid the Cold War, contemporary West Germans feared not only left-wing communism but also the resurgence of right-wing extremism and the possible coming of a Fourth Reich. Moreover, when West Germans expressed existential fears of migrants taking over German society and committing a “genocide” against the German Volk, they placed their anxieties about the future in relation to their memory and forgetting of the Holocaust. Migrants, too, must be included in the entangled histories of fear and racism. By the early 1980s, guest workers and their children increasingly feared that they would be fired from their jobs, evicted from their apartments, deported, or separated from their families. They feared that they would become the targets of verbal and physical violence, explicitly contextualizing West German racism as a continuity of the Nazis’ treatment of Jews. Return migration, too, provoked fear, as Turkish guest workers wondered what would happen to them if they returned to a homeland racked by a military coup and an economic crisis.

The dominant idea of the Federal Republic as a success story was rooted both in Cold War posturing and in postwar Germans’ efforts to distance themselves from the Nazi past.Footnote 67 Per this mythology, the stroke of midnight on May 8, 1945, the formal end of World War II, marked a “zero hour” (Stunde Null) at which Nazism disappeared and Germany was reborn. From 1945 to 1949, the Allied occupation governments reinforced this myth by overpraising their denazification programs.Footnote 68 The limited number of high-ranking Nazis indicted and sentenced in the 1945–1946 Nuremberg Trials, moreover, seemed to absolve ordinary Germans of guilt and to portray them as victims of Hitler and his henchmen. This victimhood myth was reinforced by ordinary Germans’ real trauma immediately after the war. Millions of German men were dead, in prisoner-of-war camps, or unaccounted for, and returning soldiers suffered physical and psychological scars.Footnote 69 Until the 1948 currency stabilization, Germans hungered on meager rations and resorted to trading on the black market.Footnote 70 The underground bomb shelters remained, in Jennifer Evans’s words, places of “predation, crisis, death, and decay.”Footnote 71 Up to two million women were raped by the “liberating” Soviet Red Army, while the iconic “rubble women” (Trümmerfrauen) searched through the ashes of their homes, rebuilding Germany stone by stone.Footnote 72 Millions of ethnic German expellees (Heimatvertriebene) from Eastern Europe hurried across German borders, fleeing territories under Soviet control.Footnote 73 The thousands of Black “occupation babies” born to German women and African American soldiers in the U.S. occupation zone became the targets of a new iteration of centuries-long anxiety about “race-mixing” (Rassenschande) that the Nazis had taken to a genocidal extreme.Footnote 74 The division of Germany into two separate countries in 1949 provided further fodder for narratives of victimhood, as the new border walls physically bifurcated communities and separated family members from one another.Footnote 75 Well into the postwar period, Germans clung to these “war stories,” as Robert Moeller has called them, to reject the accusation of collective guilt.Footnote 76

As Germans attempted to “recivilize” themselves after Nazism, memories of the Third Reich and the immediate postwar period shaped the way that Germans viewed guest workers and the ways in which they articulated their racism.Footnote 77 Rita Chin and Heide Fehrenbach have criticized postwar German historians’ reluctance to critically engage with the categories of “race” (Rasse) and “racism” (Rassismus), which had become taboo and silenced after the biologically based racism of the Nazis.Footnote 78 Postwar Germans, they emphasized, overwhelmingly eschewed the term Rassismus, which connotated discrimination based on biological race, and instead favored Ausländerfeindlichkeit, literally “anti-foreigner sentiment” or “hostility against foreigners,” sometimes translated as “xenophobia.”Footnote 79 Though a contentious term itself, Ausländerfeindlichkeit appeared more palatable than Rassismus because it implied a “legitimate” or “rational” criticism of foreigners grounded in socioeconomic problems and “cultural difference” (kulturelle Unterschiede) rather than biological or racial inferiority. This condemnation of migrants on the basis of culture rather than biology was part of a broader trend emerging across Western Europe in the 1980s, which scholars have called a “new racism,” “neo-racism,” “cultural racism,” and “racism without races.”Footnote 80 Many have provided strong theorizations of this development in the German case, with Maria Alexopoulou, in particular, arguing that the word Ausländer (foreigner) itself was racialized: after all, Ausländerfeindlichkeit is not used to target White migrants from countries like Sweden, Switzerland, or Australia.Footnote 81 Michael Meng, Christopher Molnar, and Lauren Stokes have further illuminated how anti-Turkish racism was central to the Federal Republic’s history both before and after reunification, describing the nuances with which Germans expressed racism in both cultural and biological terms.Footnote 82 The growing emphasis on excavating racism from the migrants’ perspectives speaks to the broader postcolonial imperative to decolonize European history and owes much to the work of scholars of Black German Studies.Footnote 83

Building on their work, this book highlights the prevalence not only of cultural but also biological racism in discussions in the early 1980s about whether and how West Germany could convince the Turks to “get out!” and “go home!” In Chapter 4, “Racism in Hitler’s Shadow,” the book traces the historical genealogy of the terms that West Germans used to discuss racism, citing the early 1980s as the critical moment at which Ausländerfeindlichkeit, previously virtually nonexistent in the German lexicon, came to dominate public discussions of racism. But, as much as they tried to deny and deflect the terms Rasse and Rassismus, both right-wing extremists and ordinary Germans alike continued to condemn Turks, Black Germans, asylum seekers, and other groups of “foreigners” by using the language of biology, skin color, and genetic inferiority.Footnote 84 While only a minority of Germans expressed overtly biological racism, the prevalence of such rhetoric alongside the rising neo-Nazi violence forced West Germans to reckon with the very existence and nature of racism itself in a country that praised itself as liberal, democratic, and committed to human rights.Footnote 85 This racial reckoning also reverberated transnationally, even creating conflict in official international affairs. Despite harboring their own ambivalent views toward the migrants, Turks in their home country exposed the hypocrisy of West German liberalism by accusing West Germans of abusing Turks, just as they had done to the Jews in the 1930s, and by comparing various West German chancellors to Adolf Hitler.Footnote 86 In line with Michael Rothberg’s concept of “multidirectional memory,” the Holocaust became a usable past that Turks could use to fight German racism in the present.Footnote 87

Anxieties about Nazi continuities were not only abstract, but also had real policy implications when it came to the legal enactment of state-sanctioned racism. The centerpiece of Chapter 5, “The Mass Exodus,” is the November 28, 1983, Law for the Promotion of the Voluntary Return of Foreigners (Rückkehrförderungsgesetz) – or the remigration law, as I call it. Initially developed during the late 1970s by the center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD), the law did not become a reality until after October 1982, when the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) took the reins of government. The CDU made “promoting return migration” (Rückkehrförderung) a core plank of its platform, and newly elected chancellor Helmut Kohl secretly expressed his desire to reduce the Turkish population by 50 percent. To fend off allegations of racism, the government’s solution was to apply what political scientists have called “checkbook diplomacy” to domestic policy.Footnote 88 Building on earlier failed attempts to financially incentivize return migration through the provision of bilateral development aid to Turkey, the 1983 remigration law unilaterally offered unemployed former guest workers a so-called remigration premium (Rückkehrprämie) of 10,500 DM, plus 1,500 for every child under age eighteen, to voluntarily leave the country by a strict deadline: ten months later. Although the law failed to achieve Kohl’s goal of repatriating half the Turks, it did lead to the mass exodus of 15 percent of the Turkish migrant population – 250,000 men, women, and children – in 1984 alone. Many who left amid this mass exodus, however, soon ended up regretting their decision. After years of ostracization as Almancı – and with no hope of assistance from the Turkish government, which had long opposed their return – they encountered both social and financial difficulties reintegrating into Turkey.

Far more so than their parents, children who returned amid the mass exodus of 1984 faced difficulties reintegrating into Turkey and became political tools in West German efforts to deny and deflect their racism. Stressing the importance of generational difference, Chapter 6, “Unhappy in the Homeland,” examines guest workers’ children who returned to Turkey in the 1980s, in many cases against their will, when their parents decided to leave. As the Turkish Education Ministry scrambled to “re-Turkify” these so-called “return children” (Rückkehrkinder) or “Almancı children” in special “re-adaptation courses,” the West German government, press, and population watched closely. Widespread reports of the children’s struggles reintegrating into their authoritarian homeland after the 1980 military coup contributed strongly to West Germans’ negative perceptions of Turkish guest worker families. By 1990, sympathy for the children’s plight compelled a rare relaxation of West German immigration policy. Just seven years after kicking them out, the government made a landmark revision to its citizenship law and allowed the children to return once again – this time to West Germany, the country that many called home. By deflecting the children’s problems onto Turkey and portraying themselves as the children’s savior, West Germans further obfuscated their own racism and reinforced their self-definition as liberal and democratic at the very moment that the Cold War ended, East Germany dissolved, and the reunified Federal Republic emerged.

Ultimately, by rethinking the early 1980s in terms of a racial reckoning, this book further challenges our idea of German identity itself. Amid the Historikerstreit of the 1980s, the renowned West German philosopher Jürgen Habermas argued that West Germans needed to further embrace what he called “postnationalism” and “constitutional patriotism”: an attachment to a country grounded not in a sense of ethnic or cultural identity, but rather in an appreciation for liberal democracy and the constitution itself.Footnote 89 This basis for national identity, he maintained, would make German society more politically inclusive and tie it closer to European supranational institutions. Despite backlash, the idea of a “postnational” Germany gained traction, especially among migration scholars who have cited the liberalization of Germany’s blood-based citizenship law in the 1990s and 2000s as evidence that Germany had, in fact, turned toward postnationalism.Footnote 90 But, as this book reminds us, the 1980s were not the 2000s. Amid the racial reckoning of the early 1980s, West Germans clung so ardently to their national and ethnoracial identity that they weaponized it – both rhetorically and violently – against the guest workers whom they had welcomed just two decades before. Back then, the debate centered not on whether to grant migrants citizenship, but rather – as embodied in the 1983 remigration law – on how to kick them out.

This reality also forces us to revise our interpretation of the onslaught of rightwing violence and far-right politics in more recent German history. One of the founding myths of the post-reunification Federal Republic is that racism was an East German import, whereby upon the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, socioeconomically downtrodden former East Germans rushed across the border, turned toward neo-Nazism, and enacted their revenge against foreigners.Footnote 91 While this interpretation holds true in certain respects, dismissing racism, right-wing extremism, and anti-migrant violence as East German imports points to an outdated Cold War mindset that views East Germans as “backward” in comparison to “liberal” West Germans and perpetuates the longstanding West German pattern of denying and deflecting racism. By complicating the post–Cold War transition, this book thus joins Jennifer Allen’s recent work in showing that, just like the mythical “zero hour” in 1945, the “fetishized” fall of the Berlin Wall and reunification in 1989 and 1990, respectively, marked not only a new era of history but also a continuity.Footnote 92 The new iteration of the Federal Republic inherited not only democracy but also the inescapable shadow of darkness, racism, and fear that had plagued West Germany for decades. And even if West Germans were not willing to admit it, Turkish migrants and their home country had been exposing this fact all along.

Muslims, Turks, and the Boundaries of “Europe”

Finally, by tying Germany and Turkey together, this book contributes to the postcolonial project of decentering Europe and expanding its imagined boundaries.Footnote 93 It shows how studying migrants’ fluid identities can change our conception of both countries’ geographic space. Here, the home country’s assertion that the migrants had transformed into “Germanized Turks,” or Almancı, is crucial. If we consider Turkish migrants as German actors (either self-identifying as German or being externally identified as Almancı), then we can broaden our scope of Germany to include Turkey. Turkey, after all, was the site of the migrants’ lives before they joined the guest worker program, as well as the place where the migrants – once they had already begun to be viewed as “Germanized” – traveled upon their temporary or permanent returns. Moreover, following the migrants on the journey itself also encourages us to consider the geographic space between Turkey and Germany as part of the two countries’ shared geography and history.Footnote 94 As they traveled on cars, trains, and airplanes across Austria, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia during the Cold War, the migrants transformed a series of seemingly distinct border checkpoints into a unified migration space, where contestations over their mobility both reinforced and eroded imagined divides.

Including Muslims and Turks as part of European history addresses what Mark Mazower has called the “basic historiographical question”: how to integrate the Ottoman Empire and its legacy into the broader narrative of European history.Footnote 95 In this task, the book speaks to scholars beyond migration studies who, amid the rise of global history, have contributed substantially to the revision of Eurocentrism by highlighting Ottoman and Turkish ties to Germany and Europe.Footnote 96 Stefan Ihrig, for one, has traced the centuries-long history of Turkish-German affairs from ancient times to the present day, while Emily Greble has argued more broadly that Islam was “indigenous” to Europe and that Muslims were crucial to “the making of modern Europe.”Footnote 97 Building on these contributions and more, this book further shows that Turkey was likewise crucial to the making of modern Germany – and vice versa.Footnote 98 The guest worker program, which sparked an unprecedented movement of people between the two countries, was pivotal to this relationship. While migration inextricably tied the two countries closer together, it also pulled them apart. As the migrants’ integration into West Germany became a proxy for Turkey’s integration into European supranational institutions, both Germans and Turks questioned where the physical and imagined boundaries of “Europe” lay and how malleable they could – and should – be.

The year 1961, which marked the signing of the recruitment agreement, was neither the start of migration between the two countries nor of Turkish-German entangled history. Rather, it emerged from centuries of diplomatic, intellectual, commercial, and cultural exchange. In the seventeenth century, when the Ottoman Empire was at its height, it ruled over a quarter of the European continent and was multiethnic, multilingual, multiracial, and multireligious.Footnote 99 In the eighteenth century, Ottomans were crucial actors in the Enlightenment, the Age of Revolutions, and the development of modern science.Footnote 100 Intellectual and ideological entanglements intensified during the Tanzimat period (1839–1876), when Ottoman administrators sought to centralize power and “modernize” and “westernize” the state by implementing reforms heavily influenced by European ideas and international pressure.Footnote 101 Yet overwhelmingly, Europeans came to homogenize Ottomans into a Muslim, Turkish “other,” or even worse into “Oriental despots” and “bloodthirsty Turks.”Footnote 102 These tensions were heightened by the brutal Habsburg-Ottoman wars and nineteenth-century Balkan nationalist movements that sought to break free from the so-called “Ottoman yoke.”Footnote 103

Despite these Europe-wide tensions, the particular relationship between Turks and Germans has often been described with fondness and cordiality – so much so that individuals in both countries at the time praised the guest worker program as the outgrowth of a centuries-long history of friendship.Footnote 104 This rhetorical trope of “friendship” was grounded in a long history of Germans’ extensive military, economic, and diplomatic ties to the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic, which complicates Edward Said’s assertion that Germans did not have a “protracted sustained national interest” in the “Orient.”Footnote 105 In 1835, Prussian officers began traveling to Istanbul to help “reform” the Ottoman army.Footnote 106 During the long nineteenth century, German intellectuals in the academic discipline of Oriental Studies (Orientalistik) harbored a curious fascination with Ottomans.Footnote 107 The Berlin–Baghdad railway, whose construction began in 1903, further tied Ottomans and Germans together commercially.Footnote 108 After the demise of the Ottoman Empire in 1923, Turkish Republican founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who had trained under Prussian military officers in the Ottoman army’s military academy, drew inspiration from Germany and Europe and channeled it into his top-down “modernization” campaigns.Footnote 109 The two countries also shared a long history of migration even before the guest worker program: since the nineteenth century, Ottomans and Turks had been a sizeable presence in Prussia and Germany, coming to Berlin in particular as diplomats, politicians, military officers, academics, journalists, and artists.Footnote 110

But this history of “friendship” was tainted with collaborations that ended in violence and genocide. During World War I, the Ottomans swiftly allied with Germany under the command of Enver Pasha, a leading perpetrator of the 1915–1916 Armenian Genocide, whom one Turkish scholar later referred to as an Almancı due to his close ties to German diplomats and intellectuals.Footnote 111 Many Germans, moreover, sympathized with the Armenian Genocide, denigrating Armenians as the “Jews of Europe.”Footnote 112 Prussian companies and military officials were even complicit by providing guns and, in rare cases, participating in or witnessing the shootings.Footnote 113 Moreover, as Stefan Ihrig has shown, Atatürk was praised in the “Nazi imagination” – and even served as an inspiration for Hitler – for his bold leadership in fostering Turkish nationalism and ethnic exclusivity through ruthlessly suppressing minority groups.Footnote 114 During the Third Reich, German intellectuals fleeing Nazism found a welcome refuge in Turkey, where many continued to study eugenics and “race science” alongside Turkish professors.Footnote 115 Turkey maintained neutrality during World War II until, upon the certainty of German defeat, it joined the side of the Allies in February 1945. Although Turkey had no official antisemitic policies, and despite rescuing some European Holocaust refugees, Turkey still persecuted the 75,000 Jews within its borders.Footnote 116 Both the memory of Ottoman atrocities and Turkey’s relationship to Nazi Germany shaped the way that observers in both countries in the 1980s discussed Germans’ anti-Turkish racism and return migration policies. This shared history of genocide became a political tool that could be condemned, whitewashed, denied, and deflected – all in the service of debating migration.

The Cold War was the key backdrop for the guest worker program, as it ushered in a new era of especially close ties between Turkey, West Germany, and Western Europe as a whole.Footnote 117 Rather than being a peripheral actor in the grand narrative of Cold War Europe, Turkey was a crucial Western ally and bulwark against communism, as it shared land borders with the Soviet Union and the oil-rich Middle East. Turkey joined the Council of Europe in 1950, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1952, and the European Economic Community (EEC) as an associate member in 1963.Footnote 118 Although it never materialized, the prospect of Turkey’s becoming an EEC member state remained very real until the late 1980s, with freedom of movement between the two countries being planned for 1986 but never implemented. Throughout the Cold War, moreover, Turkey increasingly relied on European and American loans and development aid to mitigate its economic crisis. By 1980, West Germany was Turkey’s largest trading partner, which became especially important amid the “Third World” debt crisis that devastated the Turkish economy. Although Turks often viewed these European and American ties with skepticism and debated the merits of “Westernization” and the peculiar nature of Turkish “modernity,” the overall trend was a deepening relationship throughout much of the late twentieth century.Footnote 119 Significantly, in dictating the contours of this relationship, Turkey was neither submissive nor passive. Rather, Turkish officials exerted their interests so strongly – especially their opposition to return migration – that their West German counterparts were left frustrated, frazzled, tongue-tied, and scrambling to keep up.

Ultimately, this history of “friendship” soured during the 1980s, due partly, as this book argues, to the dual swords of racism and return migration. Especially important is that West Germany passed the remigration law just three years after Turkey’s September 12, 1980, military coup, as the military dictatorship was committing rampant human rights violations against political leftists, Kurds, and other internal ethnic minorities. While historical examinations of this watershed moment largely remain to be written, this book centers the 1980 coup in nearly every chapter as a fundamental but underacknowledged part of Turkish-German migration history and transnational European history writ large.Footnote 120 Even from afar, the postcoup regime impacted migrants’ lives and return migration decisions, especially when it came to matters of education and mandatory military service for guest workers’ children. Geopolitically, tensions about the coup also trickled down into the newly overlapping contestations about return migration and asylum policies, forcing West Germany onto a shaky diplomatic tightrope. As the Turkish government assailed West German racism and strove to prevent return migration at all costs, West German officials had to balance their domestic and international interests: kicking out Turkish guest workers and preventing an influx of asylum seekers, while simultaneously appeasing a military dictatorship that, despite its human rights violations, was crucial to its Cold War geopolitical goals. As the battle over racism and return migration evolved into a battle over human rights, democracy, and authoritarianism, debates about the migrants’ integration in Germany became inextricably linked to debates about Turkey’s integration into European institutions and the ever-changing idea of “Europe” itself.

*****