Here, then, is the problem which we present to you, stark and dreadful and inescapable: Shall we put an end to the human race; or shall mankind renounce war?… The abolition of war will demand distasteful limitations of national sovereignty. But what perhaps impedes understanding of the situation more than anything else is that the term “mankind” feels vague and abstract. People scarcely realize in imagination that the danger is to themselves and their children and their grandchildren, and not only to a dimly apprehended humanity. They can scarcely bring themselves to grasp that they, individually, and those whom they love are in imminent danger of perishing agonizingly … We appeal as human beings to human beings: Remember your humanity, and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open to a new Paradise; if you cannot, there lies before you the risk of universal death … There lies before us, if we choose, continual progress in happiness, knowledge, and wisdom. Shall we, instead, choose death, because we cannot forget our quarrels? … We invite this Congress, and through it the scientists of the world and the general public, to subscribe to the following resolution: “In view of the fact that in any future world war nuclear weapons will certainly be employed, and that such weapons threaten the continued existence of mankind, we urge the governments of the world to realize, and to acknowledge publicly, that their purpose cannot be furthered by a world war, and we urge them, consequently, to find peaceful means for the settlement of all matters of dispute between them.

In this chapter we begin by highlighting the fact that proposals for the creation of an international security or peace force were actively discussed around the time of the establishment of the League of Nations and were taken up again in the period leading to the creation of the United Nations. We note that the UN Charter contains core, explicit undertakings in the area of peaceful settlement of international disputes (see Chapter 10) and what is now referred to as “peace enforcement,” and then describe the various instruments that were developed over time as the UN sought to give operational meaning to the peace and security principles embedded in the Charter. In this respect, we analyze the experience with peacekeeping operations and some of the lessons that can be drawn from their mixed success. We then analyze the extent to which there has been a fairly dramatic erosion in the effectiveness of the uses of warfare and violence to achieve particular national strategic objectives and argue that the current system of global security is absurdly costly in relation to the meager security benefits it confers. We then present a proposal – based on the work done by Grenville Clark and Louis Sohn in the 1950s/1960s – for the creation of an International Peace Force, to be established in parallel to a process of comprehensive international arms control (Chapter 9), and ensuring adequately strengthened mechanisms for the peaceful settlement of disputes(Chapter 10). Our proposal includes a discussion of a number of operational issues that emerge when considering the establishment of such a Force, many of them based on an assessment of several decades of experience with peacekeeping.

Early Attempts

The creation of an international military force to empower the League of Nations to secure the peace was actively discussed in the period leading up to the adoption of the League’s Covenant. A draft of the Covenant drawn up by former French Prime Minister Leon Bourgeois specified in considerable detail the military sanctions that would be applied against countries that disturbed the peace.Footnote 2 The Bourgeois Committee called for the creation of an international force or, as a second option, the setting up of a force made up of national contingents to be at the service of the League. A permanent international staff would provide for the organization and training of the force or coordinate the training of the national contingents and would be responsible for implementing whatever military action was ultimately endorsed by the League. Furthermore, the staff would also be given responsibility for monitoring the armaments of League members and the extent to which these were consistent with the Covenant’s disarmament provisions; it was understood that in this they would act with equanimity and independence.

According to F.P. Walters influential segments of public opinion in France “refused to believe that the League could ensure the world’s peace unless it possessed at least the rudiments of military power.”Footnote 3 Although other countries supported the Bourgeois proposal, they were not willing to take an uncompromising stance on the issue, given adamant opposition on the part of the British and American delegations. President Wilson, in particular, had argued that public opinion in America would not accept foreign inspections of the American military establishment, a point shared by the British representative, Lord Robert Cecil. In the end, the idea was abandoned, not because in and of itself it lacked merit, but mainly because the strongest advocates of the League felt that domestic political considerations would not allow for this more ambitious vision of the League’s role in the maintenance of international peace. Bourgeois’ ideas, however, were not set aside entirely. Not only was he awarded the 1920 Nobel Peace prize for his ardent support of the League, but, at the 1932 Disarmament Conference held in Geneva the French Minister for War, Andre Tardieu, proposed that all major weapons systems of all member countries be set aside and used only under a League mandate and that an international police force be placed under the jurisdiction of the Council of the League of Nations, in a regime that would also involve compulsory arbitration and a more robust sanctions regime.

The French proposal, often associated with French Prime Minister Edouard Herriot, elicited a warm response from Albert Einstein, who on November 18, 1932, issued a statement in which he made a number of compelling points: “I am convinced that Herriot’s plan represents an important step forward with regard to how, in the future, international disputes should be settled. I also consider Herriot’s plan to be preferable to other proposals that have been made.” He then went on to say that in the search for solutions the framing of the question to be addressed was essential. Rather than asking “under what conditions are armaments permissible and how wars should be fought” he argued that the starting point must be whether nations were “prepared to submit all international disputes to the judgement of an arbitration authority,” which had been established by the consent of all parties seeking to establish security guarantees. He thought that:

the renunciation of unlimited sovereignty by individual nations is the indispensable prerequisite to a solution of the problem. It is the great achievement of Herriot, or rather France, that they have announced their willingness, in principle, for such a renunciation. I also agree with Herriot’s proposal that the only military force that should be permitted to have truly effective weapons is a police force which would be subject to the authority of international organs and would be stationed throughout the world.

He then went on to identify two ways in which the Herriot proposals could be improved. First, he thought that “the police formations should not be composed of national troop units which are dependent on their own governments. Such a force, to function effectively under the jurisdiction of a supranational authority, must be – both men and officers – international in composition.” Second, in respect of the French call to train militias he indicated that:

the militia system implies that the entire population will be trained in military concepts. It further implies that youth will be educated in a spirit which is at once obsolete and fateful. What would the more advanced nations say if they were confronted with the request that every citizen must serve as a policeman for a certain period of his life? To raise the question is to answer it. These objections should not appear to detract from my belief that Herriot’s proposals must be gratefully welcomed as a courageous and significant step in the right direction.Footnote 4

The Bourgeois proposals, progenitors of the subsequent Herriot plan, had been put forward at a time when the outlines of the Covenant were still being formulated and thus could, at least in theory, be considered to have some viability. The French proposals in 1932 had little likelihood of being accepted as they would have involved a rewriting of the Covenant, something that the major powers were unwilling to contemplate. Furthermore, in putting forward these proposals and reviving the idea of an international police force, the French may have been partly motivated by their growing concerns about German militarism and the need, as they saw it, to continue to keep Germany tied to the stringent Versailles Treaty restrictions. Germany in fact soon left the League in 1933 and embarked upon a process of rapid military build-up.

In his comprehensive account of the League’s history Walters does point to the one and only – remarkably successful – international force assembled by the League in late 1934, to monitor and supervise the holding of a plebiscite in the Saar territory; a basin that had been part of Germany but had become a League mandate after the end of World War I. A contingent of some 3,300 troops made up of British, Italian, Swedish, and Dutch soldiers reached the Saar in December of 1934. Walters notes that:

From that moment all fear of disorder was at an end. The mere presence of the troops was all that was needed, and they were never called upon to use their arms. The relations between the different contingents were excellent throughout. Relations with the Saarlanders were also good: the local Nazi leaders tried at first to organize a boycott, describing the Force as a new army of occupation and ordering their followers to avoid all fraternization. But their efforts were a total failure. The troops enjoyed a popularity which they well deserved.Footnote 5

The next instance of an active debate on the possible creation of an international security force was in the period leading up to the adoption of the UN Charter in 1945. We have already discussed in Chapter 2 how a bolder vision of the United Nations considered before the October 1943 Moscow conference had to quickly adjust to the requirements of the Soviet Union under Stalin and, increasingly, to perceptions of what, in due course, would be acceptable to the US Senate, whose ratification was essential to ensure the participation of the United States in the United Nations. Three individuals that made important contributions to this debate during this period and in the years immediately following the establishment of the United Nations were Granville Clark, Albert Einstein, and Bertrand Russell. In a way that was not the case during the discussions around the League’s Covenant, the draft UN Charter generated a great deal more informed debate, from individuals who were not necessarily aligned with particular governments, but were sympathetic to the efforts of President Roosevelt and his team to bring into being an international organization to secure the peace. The motivations varied, but very much at their center was the feeling that, with the arrival of nuclear weapons, the context for warfare had changed in a fundamental way. Nations had gone to war in decades and centuries past, or had threatened to do so, assured that the costs could be maintained within acceptable levels due to the implicit constraints imposed by the state of prevailing weapons technologies.

In his discussion of the rise and fall of the “war system,” Schell gives several fascinating (and not so well-known) examples of the inexorable logic of warfare in the pre-nuclear age. In 1898, France and Britain were, for several weeks “at the edge of war over a fetid swampland, which neither country valued,” a worthless piece of land in a remote area of Sudan called Fashoda. “The disparity between the puniness of the prize and the immensity of the war being risked in Europe disturbed even the most pugnacious imperialists” observes Schell.Footnote 6 Since Fashoda, like Egypt, was on the road to India and India was the heart of the British Empire, the war logic dictated that it must be defended at all costs. In the end, though war orders were sent to the English fleet in the Mediterranean, conflict was averted at the last minute because the French backed down.Footnote 7

A second example pertains to a Franco-Russian alliance negotiated in 1894 which envisaged all-out war against Germany in the event of an attack but did not specify what the aims of such a war would be. Clausewitz had taught that absolute war always needed to be subordinated to the strategic requirements of policy, but the treaty underpinning this particular alliance put forward the idea of war as an end in itself. This is how Schell puts it: “And when General Raoul Mouton de Boisdeffre, the principal architect of the treaty on the French side, was asked what Frances’s intentions regarding Germany would be after a victory, he replied, ‘Let us begin by beating them; after that it will be easy.’Footnote 8 Regarding the war’s aim, Kennan concluded: ‘There is no evidence, in fact, that it had ever been discussed between the two governments.’”

Within a few weeks after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in an interview given to a United Press reporter on September 14, 1945, Einstein had expressed the view that “as long as sovereign states continue to have separate armaments and armaments secrets, new world wars will be inevitable.”Footnote 9 A few weeks later Russell – who, over the years, maintained an active correspondence with Einstein – rose in the House of Lords on November 28 and said:

We do not want to look at this thing simply from the point of view of the next few years; we want to look at it from the point of view of the future of mankind. The question is a simple one: Is it possible for a scientific society to continue to exist, or must such a society inevitably bring itself to destruction? It is a simple question: but a very vital one. I do not think it is possible to exaggerate the gravity of the possibilities of evil that lie in the utilization of atomic energy. As I go about the streets and see St. Paul’s, the British Museum, the Houses of Parliament, and the other monuments of our civilization, in my mind’s eye I see a nightmare vision of those buildings as heaps of rubble with corpses all round them. That is a thing we have got to face, not only in our own country and cities, but throughout the civilized world.Footnote 10

As noted earlier in this book, with his typical mathematician’s logic, Russell, in an article for The American Scholar in 1943/44 had written: “Wars will cease when, and only when, it becomes evident beyond reasonable doubt that in any war the aggressor will be defeated.”Footnote 11 Meaning that with an international security force effectively having a monopoly on the use of military power, no nation would use force against another nation because it would not have the means to confront a multinational response. Moreover, beyond responding to such a threat, many nations have increasingly internalized the values and principles of peaceful coexistence and the norm of international nonuse of force with the advent of the 1945 Charter (see Chapter 10); such an internalized value should continue to be consolidated in the future, making violations of international law in this respect an even more deeply held taboo.

Einstein expanded upon his earlier interview in a radio address on May 29, 1946, by stating:

The development of technology and military weapons has resulted in what amounts to a shrinking of our planet. Economic intercourse between countries has made the nations of the world more dependent upon one another than ever before. The offensive weapons now available leave no spot on earth secure from sudden, total annihilation. Our only hope for survival lies in the creation of a world government capable of resolving conflicts among nations by judicial verdict. Such decisions must be based upon a precisely worded constitution which is approved by all governments. The world government alone may have offensive arms at its disposal. No person or nation can be regarded as pacifist unless they agree that all military power should be concentrated in the hands of a supranational authority, and unless they renounce force as a means of safeguarding their interests against other nations. Political developments, in this first year since the end of the Second World War, have clearly brought us no closer to the attainment of these goals. The present Charter of the United Nations does not provide either for the legal institutions or the military forces which would be necessary to bring real international security into being. Nor does it take into account the actual balance of power in the world today.Footnote 12

He then went on to suggest that the United States and Russia as the main victorious war powers could, by themselves, create the legal framework that would ensure universal military security.

Clark was no less active. As the main adviser to US Secretary of War Henry Stimson, Clark had been involved in most important decisions on the conduct of the war and had seen up close the dire consequences – human, economic, political – of global warfare. In the summer of 1944, when it became increasingly clear that the Allies would emerge victorious, Clark, who had spent several years in Washington as an unpaid public servant, staying with his wife at a suite at the St. Regis hotel, decided to return to law practice in New York and was told by Stimson: “Grenny, go home and try to figure out a way to stop the next war and all future wars.”Footnote 13 Clark’s A Plan for Peace, published in 1950 contains a first set of fairly detailed proposals for the creation of a Peace Force attached to the United Nations;Footnote 14 we will say more on this later in this chapter.

The UN Charter and the Peaceful Settlement of Disputes

The United Nations came into being against the background of over 60 million casualties, the destruction of significant portions of countries’ physical infrastructure, and the associated economic collapse. It is not surprising therefore that the Charter refers in high-minded language to the determination of the international community to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war,” lays out various principles for the peaceful coexistence of its members and calls for the strengthening of existing mechanisms of cooperation “to maintain international peace and security.” Article 1 of the Charter, in particular, specifically refers to the UN taking:

effective collective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace, and for the suppression of acts of aggression or other breaches of the peace, and to bring about by peaceful means, and in conformity with the principles of justice and international law, adjustment or settlement of international disputes or situations which might lead to breaches of the peace.

The principles that are to guide United Nations actions in this area are spelled out in Chapters VI and VII of the Charter on the Pacific Settlement of Disputes (Articles 33–38) and Action with Respect to Threats to the Peace, Breaches of the Peace, and Acts of Aggression (Articles 39–51), respectively. The Articles embedded in Chapters VI and VII are an attempt to establish a foundation of legal and moral legitimacy to enable a range of UN actions intended to protect the peace. In the paragraphs that follow we will review briefly what mechanisms emerged, in practice and over time, to operationalize some of the noble sentiments contained in the Charter in this area, so central to what the UN was set out to achieve.

The peaceful settlement of disputes (Chapter VI) was seen as an essential element of avoiding armed conflicts (see also Chapter 10). However, at the insistence of the Big Four during the drafting stage of the UN Charter, Article 2(3) narrowed the scope of dispute settlement to international cross-border disputes, with internal disputes falling within the sovereignty of states.Footnote 15 This was done to protect state prerogatives as most governments were unwilling, in 1945, to have an international organization interfering in internal disputes. Initially, this sharply curtailed the sphere of action of the UN, given that the overwhelming majority of conflicts in recent decades have been of an internal nature.Footnote 16 And it also added an additional layer of complexity to potential UN responses given the nature of such internal conflicts, with the fighting often taking place between militias, armed civilians and guerrillas with ill-defined front lines and with civilians often being the victims of the brunt of the violence. These internal conflicts also proved to be destructive of state institutions in a way that traditional interstate conflicts with well-defined frontlines were not.

Article 33 of the Charter identifies the various mechanisms that are to be used by the parties to a dispute seeking to peacefully settle their differences. Article 51, however, allows for the interim use of countermeasures and a narrow but inherent right of self-defense by states, with an obligation to report such cases immediately to the Security Council so that it may take the necessary measures to secure international peace and security, in line with its authority and responsibility. In time, the United Nations developed a range of instruments aimed at resolving conflicts between and within states entailing aspects of preventive diplomacy, peacekeeping, disarmament, sanctions, and the like. It also sought to define and operationalize some of these instruments in a formal way, typically in the context of General Assembly resolutions. For instance, members could enter into negotiations to address various types of conflict – political, social, legal and so on. Negotiations are limited to the states concerned, which are empowered to “shape its outcome to deliver a mutually agreed settlement.”Footnote 17 For their success, negotiations assume the willingness of states to compromise, but may imply the imposition of solutions on the weaker party. Thus, to take an example, a negotiation between China and the Philippines on the status of various small islands in the South China Sea might not lead to results satisfactory to the latter party, given the lopsided nature of both parties’ relative strengths.

In an inquiry or process of fact finding, the parties may initiate a commission of inquiry to establish the facts of the case, but the recommendations would not usually be legally binding. Mediation generally involves the good offices of a third party to assist in finding a resolution and to prevent escalation. It is seen as perhaps the oldest and most often used method for peaceful settlement and was enshrined in The Hague Conventions on the topic of 1899 and 1907. Conciliation is a combination of fact finding and mediation to propose a mutually acceptable solution to parties in dispute. Conciliation proposals are not binding, but parties may accept them unilaterally or through agreement; many international treaties contain provisions for the referral to disputes to compulsory conciliation. GA resolution 50/50Footnote 18 of 1995 establishes the UN framework for conciliation. Arbitration, first set out in The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, employs settlement by arbitrators of the parties’ choice, in a manner intended to be consistent with prevailing legal standards. Parties agree to abide by the outcome, which is binding. Arbitration has been used in territorial disputes or, for example, when parties may differ in their interpretations of bilateral or certain multilateral treaties. International tribunals refer mainly to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the range of other international courts and tribunals, most of which have been established since the adoption of the Charter. The decisions of the ICJ are final and cannot by appealed.Footnote 19 International tribunals, which have proliferated in the modern era, are used, for example, to clarify or settle interpretation and application of treaties, border disputes among states, matters related to the Law of the Sea, the international use of force, the application of cross-border investment agreements, and individual liability for war crimes, among other things.Footnote 20

The Charter encourages the involvement of regional agencies in the settlement of disputes under its Article 52. Such regional bodies may include the Arab League, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Organization of American States (OAS), the African Union (AU), the Council of Europe, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the European Union (EU), as well as others. An important challenge in the effective operation of regional mechanisms has been how to harmonize their work with that of the United Nations itself. However, when regional efforts fail, the situation may be referred to the Security Council, where the most vital question then becomes whether the dispute threatens international peace, thus falling within the Security Council’s mandate.

Development of the Concept of a Standing Force

Article 43(1) of the UN Charter states: “All Members of the United Nations, in order to contribute to the maintenance of international peace and security, undertake to make available to the Security Council, on its call and in accordance with a special agreement or agreements, armed forces, assistance, and facilities, including rights of passage, necessary for the purpose of maintaining international peace and security.” Article 43 was considered, by the drafters in San Francisco, to be absolutely fundamental to the new centralized collective security mechanism of the Charter. However, remarkably, these Chapter VII provisions were never implemented and thus, the Security Council had not actually had, armed forces at its disposal even though Article 24(1) establishes that the Security Council bears “primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security” when parties are unable or unwilling to settle their disputes peacefully, or other situations arise. Faced with a host of conflicts and destabilizing situations in various parts of the world, a number of initiatives have emerged from within the UN to bridge the gap between its peace and security mandate and the absence of appropriate instruments to carry it out.

For instance, in 1948 Secretary General Trygve Lie proposed the creation of a “UN Guard Force” of up to 5,000 soldiers to be recruited internationally, mainly to assist in the administration of truces, protecting the transparency of plebiscites and other duties of a limited nature, not unlike those of a constabulary nonparamilitary force. Lie made it clear that his proposal was not intended as a substitute for the armed forces that were to be made available to the Security Council “as soon as possible” under Article 43, but still encountered strong opposition from the Soviet Union representatives, who did not feel comfortable with an even minimalist interpretation of the commitments made in that Article. Although Lie went out of his way to emphasize that it would not be a striking force, that it would be at the disposal of the Security Council and the General Assembly, and that it would be largely used in the administration of plebiscites and in the supervision of truce terms, he was forced to water down his proposal to an 800-person UN Guard. According to Roberts, even the United States, the United Kingdom, and France had expressed reservations about the scale of such a force, with the US representative stating that, “[w]e are inclined to think that the original proposal was somewhat too ambitious, and that it did encroach somewhat on the military theme.”Footnote 21 This stands in sharp contrast to the initial thinking within the US government in discussions leading to the ratification of the UN Charter when, according to Urquhart, “the United States estimate of the forces it would supply under Article 43, which was by far the largest, included twenty divisions – over 300,000 troops – a very large naval force, 1,250 bombers and 2,250 fighters.”Footnote 22 This swift change in attitude seems to have been precipitated by the onset of the Cold War and Soviet demands that all the great powers make equal contributions, irrespective of their relative size.

Lie, however, was persistent and he took advantage of the outbreak of the Korean War in June of 1950, the UN’s authorization for a US-led force to repel North Korea’s attack and the General Assembly’s call in its Uniting for Peace resolution alluded to previously (see Chapter 4) – which called on its members to keep forces trained, organized and equipped for UN serviceFootnote 23 – to propose the creation of a UN Legion made up of volunteers. But, by 1954 Lie’s successor, Dag Hammarskjold, withdrew such proposals from further consideration and the issue itself retreated as the patterns of the Cold War became entrenched and significantly intensified.

Dag Hammarskjold sought to make a distinction between “quiet diplomacy,” consisting mainly of the involvement of the Secretary General in bringing together the parties in conflict, and “preventive diplomacy” which consisted in developing and nurturing the infrastructure for peacekeeping operations. Article 98 of the Charter had granted the Secretary General the right to “perform such other functions as are entrusted to him” by the various UN organs and Hammarskjold was proactive in projecting the role of the UN as peacekeeper in a number of instances, such as during the 1956 Suez Canal crisis and in the early 1960s in the Congo, not always with the full support of the membership.

After 1956 peacekeeping forces and the infrastructure around them developed gradually through the introduction of so-called standby arrangements, which Roberts defines as “national contingents which were made available for particular UN operations through specific agreements with the troop-providing governments.”Footnote 24 The debate about replacing these with a standing force took place largely in the academic community, with proposals such as that put forth by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 1957,Footnote 25 and the more substantive and ambitious work done by Clark and Sohn in 1958 and in the following years.

The end of the Cold War prompted a more active approach to peace enforcement and conflict management and prevention by the UN. In particular, it boosted in a major way the role of the Security Council in this area and led to a sharp increase in the number of peacekeeping missions mandated by the Council. With the collapse of tightly centralized control in countries such as the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, festering, long-repressed conflicts – often with an ethnic or religious underpinning – suddenly came to the fore, which was reflected in a much larger number of peacekeeping operations deployed. For instance, while in early 1988 there were ten such operations in place involving about 9,600 military personnel, by the end of 1994 there were 34 operations employing 73,400 troops. (As was noted in Chapter 12 on funding the United Nations, spending on peacekeeping operations rose from under $30 million in 1971 to close to $9 billion in 2017.) Furthermore, the Security Council has broadened the scope of its attention beyond conflict prevention and management to include humanitarian issues, monitoring human rights abuses, terrorism, democratization, the promotion of gender equality, the building up of court systems, and so on. The General Assembly’s role has become more muted in contrast to the pre-end-of-the-Cold War era where it at times occupied the space created by Security Council gridlock, brought about by the frequent use of the veto.Footnote 26 Article 99 gives a role to the Secretary General in the area of the maintenance of international peace and security, and various secretary generals over time have taken an activist role in this area, often serving as mediators in a range of conflicts or coming forward with various initiatives that would enhance the peace promotion mandate of the UN.Footnote 27 Examples include important roles played by secretary generals in conflicts in the Middle East, Southern Africa, the Iran–Iraq war, Soviet involvement in Afghanistan in the 1980s, and Namibian independence, to name a few.

An Agenda for Peace 1992 was an early attempt to give new life to the United Nations’ role in this area, with Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali putting forth a range of proposals, including a possible return to the spirit and the letter of Article 43. While admitting at the outset that readily available armed forces on call “may perhaps never be sufficiently large or well enough equipped to deal with a threat from a major army equipped with sophisticated weapons … they would be useful, however, in meeting any threat posed by a military force of lesser order,”Footnote 28 the Secretary General put forth the idea of creating “peace enforcement units” to support the work of peacekeepers in maintaining ceasefires. Their mandate would be clearly defined and would be made up of troops who had volunteered for such service.

Brian Urquhart, a former Under-Secretary General of the UN published an influential piece in the New York Review of Books in 1993 in which he argued that the time had come to revive Trygve Lie’s 1948 idea. The problem with the Security Council was now less the abuse of the veto by the major powers and more its inability to carry through on its decisions, with this flaw having tragic real-life consequences on the ground, such as in Rwanda and Bosnia. With reference to Bosnia in particular, he argued that “a determined UN peace enforcement force, deployed before the situation had become desperate, and authorized to retaliate, might have provided the basis for a more effective international effort.”Footnote 29 Urquhart identified flaws in the UN’s peacekeeping arrangements that have largely remained unchanged in the 25 years since he made his case, provoking spirited debate. Key among existing flaws is the unwillingness of governments to put their troops in harm’s way for conflicts perceived to take place in distant lands that could at times be both violent and open-ended. Because peacekeeping forces not only report to the UN command but also to their own country’s military commands, the authorities at home have a built-in bias not to intervene, in the interests of minimizing casualties, among other reasons. Over time, this has resulted in massive tragedies, such as Srebrenica in 1995 when, as noted by Autesserre, “the Dutch commander of a peacekeeping battalion, outnumbered and outgunned, had his soldiers stand by as Serbian forces rounded up and killed some 8,000 Muslim men and boys.”Footnote 30

But this was not the only problem. Peacekeeping forces are often poorly trained and equipped. They are put together in response to the emergence of conflicts and often, as in Rwanda, arrive too late to make a difference. A standing force of volunteers would address the problem of training by providing this on an ongoing basis; hence the use of the equivalent term “rapid reaction” to highlight a state of readiness that is not to be found in forces that are put together in calls to members by the Security Council, which then has to await for offers of help from interested parties. In this respect, by strengthening the ability to prevent conflicts, such forces could help minimize the terrible human and social costs (not to mention economic and financial inefficiencies) of late interventions. The volunteer nature of enhanced arrangements, likewise, could be expected to deflect the possible political ramifications associated with contingents that are drafted by their respective governments into peacekeeping roles. As we shall see below, these issues are all addressed in the proposals we put forward for an International Peace Force.

Perhaps no other failed UN intervention highlighted the weaknesses of current approaches to peacekeeping than the events in Rwanda in 1994 when, over a period of slightly more than four months 800,000 people were killed. This large-scale genocide of primarily Tutsis was at a time when, in the consensus of experts and subsequent inquiries made to assess what had gone wrong, a modest-sized international force could have prevented much of the killing.Footnote 31, Footnote 32

Upon taking office in early 1997, Secretary General Annan placed conflict prevention at the top of the UN agenda and spoke of shifting the United Nations from a “culture of reaction to a culture of prevention,” stating that “one of the principal aims of preventive action should be to address the deep-rooted socio-economic, cultural, environmental, institutional, and other structural causes that often underlie the immediate political symptoms of conflicts.”Footnote 33 Peaceful settlement was thus seen as being closely linked to conflict prevention, with the latter also aiming to address the deeper causes of conflict – poverty, inequality, corruption, lack of opportunity, human rights violations, to name a few (see discussion of addressing these issues more systemically at the global level in Chapters 13–18). Therefore, conflict prevention at UN missions and by bilateral and multilateral actors should address the interconnections and the tensions between security and economic and social development.

In July 2006 Annan further widened the scope of conflict prevention by referring to “systematic prevention,” taken to mean “measures to address global risks of conflict that transcend particular states.”Footnote 34 The Rwandan Genocide played a catalytic role in these discussions and in the negotiation of the Rome Statute for the International Criminal Court (ICC), which entered into force in 2002, allowing for the prosecution of war criminals; its explicit intention to battle against impunity for grave international crimes was expected to play an additional role in deterring conflict and abuse (see Chapter 10).

Efforts since the end of the Cold War to operationalize the UN’s conflict prevention mandate have not been free of controversy. Some have argued that because preventive diplomacy could involve the use of force, the Security Council should focus its efforts on funding UN peacekeeping and enforcement rather than the less well-defined issue of conflict prevention. Very often states come to the Security Council after the crisis has erupted and the opportunity for prevention is long gone. Some countries see prevention as a justification for intervention; furthermore, developing countries saw a trade-off between a peace and security focus and, in a world of constrained resources, a lack of focus on social and economic development needs. And finally, it was not always clear what “conflict prevention” meant in practice and this has complicated countries’ involvement. In his Supplement to An Agenda for Peace, issued in 1995 on the occasion of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the United Nations, Secretary General Boutros-Ghali noted that “when in May 1994 the Security Council decided to expand the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), not one of the 19 Governments that at that time had undertaken to have troops on stand-by agreed to contribute.”Footnote 35 Indeed, this situation was repeated when, in the aftermath of the genocide, the Secretary General issued appeals to 60 governments for troops for a peacekeeping force to protect 1.2 million Rwandan refugees in camps in Zaire and he received a total of zero responses, again underscoring the fatal flaw associated with the absence of a permanent standing force.

Peace Enforcement: Further Considerations

There are significant differences in the types of UN operations that have emerged in the context of the application of the principles contained in Chapter VII of the Charter. One issue that has emerged is the asymmetric nature of peace enforcement operations under this chapter, which in recent decades have involved mainly events in poorer, developing countries as the main threats addressed by the peace and security mandate of the United Nations. This asymmetry is not unlike that which exists in International Monetary Fund operations, with the Fund having considerable leverage in shaping national domestic policies for those countries (generally in the developing world) that borrow from it, and the organization having little influence in helping reverse unsustainable policies in countries that are systematically important and that may pose threats to the global economy (see Chapter 15). A prime example of this is the 2008–2009 global financial crisis, which eloquently revealed the inability of the IMF to coerce some of its largest shareholders into adopting regulatory regimes for their financial sectors that might be consistent with global financial stability.

Peace enforcement operations have generally been delegated to governments or groups of countries working as part of a coalition, with such operations a way in which the Security Council seeks to impose its will via military or economic actions. These operations may involve the protection of supplies in war-torn areas, ensuring freedom of movement, or securing agreements against various parties that may be seeking to undermine the peace. The Security Council has sought to use a combination of economic and military power with the relative importance of each depending on individual country circumstances. The first Chapter VII operation took place in Korea in 1950 and was only made possible by the absence of the Soviet Union from the Security Council at the time. Article 47 of the UN Charter calls for the establishment of a Military Staff Committee to “advise and assist the Security Council on all questions relating to the Security Council’s military requirements for the maintenance of international peace and security, the employment and command of forces placed at its disposal, the regulation of armaments, and possible disarmament.” This initiative fell victim to the onset of the Cold War in the late 1940s and the Committee has never played the role foreseen in the Charter and, thus, Chapter VII operations remained dormant for several decades.

The next Chapter VII interventions came in 1991 with the invasion of Kuwait by Saddam Hussain’s Iraq and authorization in 2001 for the establishment of an International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. Peace enforcement operations have not been free of controversy, with many critics stating that the distinction between pacification and militarism has been blurred over time. Such critics point, for instance, to the fact that until relatively recently (up to the time of the failed Somalia intervention in the early 1990s) the US military itself did not unambiguously identify the differences between “war,” peace enforcement, and peacekeeping. In any case, none of the above interventions involved the United Nations at the operational level but were largely based on US political leadership and military deployment, with no UN input to speak of. This may have reflected an established tradition that saw UN soldiers (“The Blue Berets”) as an element of peaceful diplomacy with strict controls on the use of fire, typically limited to cases of self-defense. One further limitation or drawback of interventions led by a country or group of countries – in the absence of a UN force under the jurisdiction of the Security Council – is that an impression can be created that the operations are mainly serving the strategic interests of the country or countries contributing troops and equipment, rather than the interests of the international community as reflected in the will of the United Nations. This, in turn, may contribute to undermine the legitimacy of the intervention. This particular problem would, of course, be addressed in the context of a UN International Peace Force where the command and control would be wholly under UN auspices; we will say more on this in the sections below.

The 1960 Congo mission was the first where UN peacekeepers were allowed to enter into military action but found themselves poorly prepared. This early intervention experience succeeded in eroding the consensus for peacekeeping, with states henceforward seeking short mandates to be renewed only if not vetoed by the Security Council. In other instances, peacekeepers (e.g., Cambodia, 1992–1993) relied on the consent of the government and were required to withdraw even in the face of limited opposition.

The failures in Somalia, Yugoslavia, and Rwanda in the first half of the 1990s, in turn, greatly undermined the credibility of traditional peacekeeping. A permanent tension emerged between the objective of peacekeeping and peace enforcement despite UN efforts to update existing mandates, as was the case in Somalia. At times Security Council resolutions could not be implemented because of the lack of adequate ground force capability to either put a stop to the conflict or to protect safe areas. An example of this tension was French President Chirac’s proposal to retake Srebrenica, which was opposed by the British who argued that the UN force had no mandate to go to war. Or the position taken by the United States, the United Kingdom, and France that prevented the Security Council from rescuing Tutsis during the Rwandan genocide and the associated denials that genocide was in fact even taking place. Indeed, in the case of France, critics have pointed to the fact that the country supported the Hutus on account of strong historical, political, and economic links, largely turning a blind eye to the killing. A third example of a failed, ineffective UN operation concerns Darfur, where the UN and the African Union “decided that respecting Sudanese sovereignty was more important than conducting a military response capable of protecting the civilian population.”Footnote 36

UN action to secure the peace has been obliged to operate against the background of the constraints imposed by narrow interpretations of Article 2(7) of the Charter, which states that “nothing contained in the present Charter shall authorize the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state.” Given that, as noted earlier, most conflicts over the past half a century have largely been internal in nature, the end result has often been an approach to peacekeeping and peace enforcement that is overly timid and, hence, ineffective. States in the middle of a conflict have often been reluctant to accept UN involvement, reflecting the primacy of national sovereignty over security and/or humanitarian considerations, and the the organization has itself contributed to the creation of a culture that embodies the belief that “the United Nations cannot impose its preventive and peace-making services on Member States who do not want them.”Footnote 37 These attitudes, in turn, led to the emergence of a set of overly limited “principles” of peacekeeping which included such concepts as the consent of the parties, neutrality, and the nonuse of force except in cases of self-defense. The idea that the UN should remain neutral between warring parties without a mandate to stop the aggressor and impose a cessation of hostilities flow from a design flaw in the UN Charter, reinforced by the Big Four’s desire not to grant the UN any concrete and effective (as opposed to theoretical, “on paper”) responsibility to actually deliver on the peace and security ideals of its Charter. As we will see below, in our proposals for the creation of a United Nations International Peace Force, there is an urgent need to move to a system of genuine collective security and conflict prevention, where the primary aim of the United Nations is to secure the peace and protect citizens from the effects of violence in an impartial manner, as opposed to entrenching a too-narrow view of state sovereignty, to the detriment of all.

In many cases of UN intervention a key question has often been: Can peace enforcers challenge the sovereign right of domestic authorities to do as they please, which may often involve persecutions, killing, and other forms of massive human rights violations? Can humanitarian motives in fact be grounds for international enforcement action? The Somalian failure very much brought humanitarian justification into the center of the debate on the nature of UN peace enforcement. Secretary General Boutros-Ghali made the argument that in chaotic domestic environments characterized by massive abuses, the need for humanitarian interventions should take precedence over concerns about state sovereignty. Later on, Secretary General Annan made a case for a redefinition of state sovereignty that was consistent with the rights of individuals to peace and security. This thinking underpinned the justification used by NATO for its intervention in Yugoslavia in 1999, with peace enforcement for the protection of populations leading to the development of the concept of the “responsibility to protect” (“R2P”), reflected in the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document of global leaders.

The remarkable high-level acceptance of the R2P doctrine was preceded by the 2001 International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS), established by the Canadian government, with Gareth Evans, former Foreign Minister of Australia, and Algerian diplomat Mohamed Sahnoun, serving as cochairs.Footnote 38 In a nutshell, the commission report recommended “three pillars” to the R2P doctrine, with principled collective military action employed only as a last resort. The ICISS underlined, first, the primary responsibility of every state to protect its own populations from atrocity crimes (e.g., genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity), in accordance with their national and international obligations, with a second, parallel responsibility of the international community to encourage and support states in fulfilling their responsibilities. Only when a state is manifestly failing to protect its population should the international community take collective action, first employing appropriate diplomatic, political, humanitarian means, and then, if necessary, military means, in accordance with the Charter. The R2P norm has been the object of very substantial civil society engagement and support, with a convened International Coalition for the Responsibility to Protect (ICRtoP).Footnote 39 The doctrine has informed multiple resolutions of the Security Council and other UN organs since its adoption by the World Summit in 2005.Footnote 40

One challenge faced by the UN in Chapter VII operations has been, as noted above, the generally low level of enthusiasm by UN states to participate in enforcement operations. Many states seem to be of two minds as regards their collective responsibilities under Chapter VII as UN members and their propensities to zealously safeguard notions of domestic sovereignty regardless of circumstance. In An Agenda for Peace in 1992 the Secretary General recommended that under Article 40 of the Charter the Security Council consider using peace enforcement units in clearly defined circumstances, but the veto-wielding members showed little interest. Recourse to regional organizations has also not produced the desired results because these have generally been poorly equipped in operational military capacity for multilateral roles. A related problem pertains to the difficulties faced by parties involved in a military intervention in maintaining adequate levels of impartiality. Michael Pugh argues that “the concept of peace enforcement remains an extremely underdeveloped area of military doctrine – even though it is perhaps most needed.”Footnote 41

The International Evolution of War and Violence: A Story of Diminishing Returns

At the same time and in parallel to these incomplete and rather erratic efforts at the United Nations to give reliable operational meaning to Chapter VII Charter commitments, there have been significant changes in our understanding of the use of violence to achieve political ends. One need not be naïve about the future of warfare to understand the constraints that have emerged in recent decades on the use of violence as a result of developments in technology and the process of economic integration. International warfare in centuries past was characterized by great disparities of power, with conquering nations enjoying a superior technological advantage, which could be used to overwhelming effect. Hernan Cortes subjugated the vast Aztec civilization with a grand total of 500 men, 10 bronze cannons and 12 muskets. A similar story can be told about Francisco Pizarro and his band of adventurers and religious fanatics in respect of Atahualpa and the battle in Cajamarca where fewer than two hundred Spanish soldiers, with horses and some firearms, overcame an army of 80,000 Incas.Footnote 42 Whether we refer to the arrival of Robert Clive in India, the opium wars in China, Commodore Perry’s sailing into Japanese waters to compel the Japanese to trade with the rest of the world, or the excesses of African colonization, military might in centuries past was extremely effective in delivering (ill-gotten) economic and political power, in subjugating other peoples, and empowering and enriching those that had the technological advantage.

But that period is long gone and what has emerged is a rapid and irreversible erosion in the ability of military power to deliver the spoils of the past. The arrival of nuclear weapons and the spread of democratic forms of governance, plus a greater recognition by people everywhere of what the anthropologist Robert Murdock calls “the psychic unity of mankind,” the sense that the differences between various cultures and nations – which have frequently figured prominently as justifications for war – are sometimes artificial and often skin-deep, have contributed to shift in a dramatic way the trade-off between the utility of violence and the costs of violence.Footnote 43 And thus, we have a growing list of examples of some of the most powerful states in the world – often endowed with nuclear weapons and the ability, at least in theory, to totally obliterate their adversaries, having to face military humiliations. Schell points to nuclear-armed Britain failing to achieve any of its strategic objectives in the Suez crisis of 1956 against Egypt; France was not able to retain control of Algeria during its war of independence; the United States and the Soviet Union failed utterly in Vietnam and Afghanistan, respectively, and China had its own unsuccessful border disputes with Vietnam in 1979 and the ensuing years.Footnote 44 The presence of the Soviet Union and China in this list suggests that one cannot appeal to the argument that there is something inherently decent in democratic regimes that makes the use of nuclear weapons to achieve strategic objectives an impossibility.Footnote 45 The issue here is that the world has come around to agree with President Truman, who once remarked that “starting a nuclear war is totally unthinkable for rational men” and that it will never make any sense to shed the blood of millions for some marginal, perceived strategic advantage.

While it has always been ethically unacceptable (and is now seen as such by many populations around the world), the use of violence as an instrument to promote the national interest has also thus been undermined by the very sharp increase in the costs – economic, human, political – of its use. This, of course, is not to say that the world is protected from the delusions of the powerful. It does not mean that World War III will be forever averted. We have not yet devised a system of governance that permanently protects citizens against the dangers of mentally unstable or irrational leaders (which, by and large, are still overwhelmingly men) from rising to power and misusing that power, too often linking military demonstration with types of national “honor” or prestige. But, the calculus of war has shifted and has shown that the utility of violence as a tool to achieve national ends is a pale shadow of what it was in the pre-nuclear days. Nuclear mass extermination was never and is hardly ever likely to be an attractive political option.

In 2002 the United States released its National Security Strategy. Formulated in post–September 11 days of 2001, it postulated an extremely muscular view of the country’s role in the world, one in which the United States – in the words of the US president – “has, and intends to keep, military strengths beyond challenge, thereby making the destabilizing arms races of other eras pointless, and limiting rivalries to trade and other pursuits of peace,” but also one in which US “forces will be strong enough to dissuade potential adversaries from pursuing a military build-up in hopes of surpassing, or equaling, the power of the United States.” The experience, in practice, however, has been enormously more complicated, and costly. American interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan have been extremely expensive. According to the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University, through the 2017 fiscal year the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, and Veteran Affairs had spent about $4.3 trillion on the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Syria since 9/11.

A large share of this consisted of so-called Overseas Contingency Operations, which are subject to special appropriations and the bulk of which were accounted for by the first two of the countries listed above. This sum – equivalent to some 23 percent of GDP in 2017 dollars – is expected to be augmented by at least another trillion dollars (5.4 percent of GDP) in respect of future health and other benefits expenditures for US veterans. Given the ubiquitous presence of budget deficits in the United States over the past many years (18 years of consecutive budget deficits since 2001 and projected deficits for the foreseeable future), much of the military spending has been associated with a remarkable rise in public indebtedness. It is thus necessary to factor into the costs of Iraq and Afghanistan the burden on the budget of additional interest payments on the public debt, which could easily add another 15 percent of GDP. But these numbers, dire as they are, only capture accounting costs, not opportunity costs and productivity losses. How many net additional million jobs could have been created by redirecting some of the monies allocated to the war effort to investments in healthcare, infrastructure, clean energy, education, and other productivity-enhancing areas?Footnote 46 Would a trillion dollars make a difference in the fight against cancer or the mental illnesses that afflict a growing share of the US population? The questions are too painful to raise.

The above is not to suggest that all the above military spending was an entirely wasted effort. The goal of dislodging the Taliban from power in Afghanistan and, for instance, thereby helping release its 11 million women and girls from the restrictions imposed on them by the mental obscurantism of its men, had considerable support in the countries that eventually joined in the war effort. The point is rather to highlight that, almost 20 years later, there is no certainty that, in the absence of further deployment of financial resources to maintain a military presence there, the Taliban would not, in fact, stage a comeback taking us, full circle, back to the beginning of the war, with little to show that would even closely match the scale of the financial effort, to say nothing of the cost in lives.Footnote 47

Which brings us back to Schell’s principal insights in The Unconquerable World: the utility of violence has dramatically declined in recent decades as a tool for the promotion of the national self-interest and:

violence, always a mark of human failure and a bringer of sorrow, has now also become dysfunctional as a political instrument. Increasingly, it destroys the ends for which it is employed, killing the user as well as the victim. It has become the path to hell on earth and the end of the earth. This is the lesson of the Somme and Verdun, of Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, of Vorkuta and Kolyma; and it is the lesson, beyond a shadow of a doubt, of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.Footnote 48

Our current system of governance and our efforts to provide peace and security at reasonable cost fail utterly (see Chapter 9). On the whole, it is a massive waste of public resources because it does not achieve even some of the most elementary strategic objectives established at the outset of the hostilities. And, in the nuclear age (with also a range of other weapons of mass destruction existing or on the cusp of development), it holds the seeds of our potential collective destruction.

The Institute for Economics and Peace, an independent nonpartisan think-tank, estimates that the total economic impact of violence in 2017 was in the order of $14.8 trillion, equivalent to 18.5 percent of world GDP or $1,988 per annum per person. Direct costs associated with violence include accounting losses linked to government spending on the military, judicial systems, healthcare, and police. Indirect costs capture losses resulting from violence perpetrated in the course of the year and would include such items as productivity losses resulting from injuries, foregone economic output resulting from premature fatalities associated with murder, as well as reduced economic growth because of prolonged war or conflict. The report analyses three broad categories of costs: security services and prevention-oriented costs; armed conflict related costs; and costs resulting from interpersonal violence.Footnote 49 The two largest contributors to the costs of containing global violence are military expenditures – accounting for 37 percent of the total cost – and internal security expenditures, which mainly capture preventive actions linked to police, judicial and prison system spending and account for 27 percent of the total. It then follows that the total economic impact of violence is approximately 105 times more than annual Official Development Assistance and exceeds the total net outflow of global foreign direct investment by a factor of eight. It also exceeds by a factor of about 350, total annual lending commitments made by the World Bank. The individual country costs range from over 50 to 70 percent of GDP in countries such as Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, to less than 3 percent of GDP in Japan, Switzerland, Austria, Iceland, Canada, and Denmark. Clearly, the establishment and implementation of an effective “International Peace Force,” to centralize and contain global security spending, could have vast security and economic ramifications, releasing substantial resources to promote economic and social development and shared prosperity.

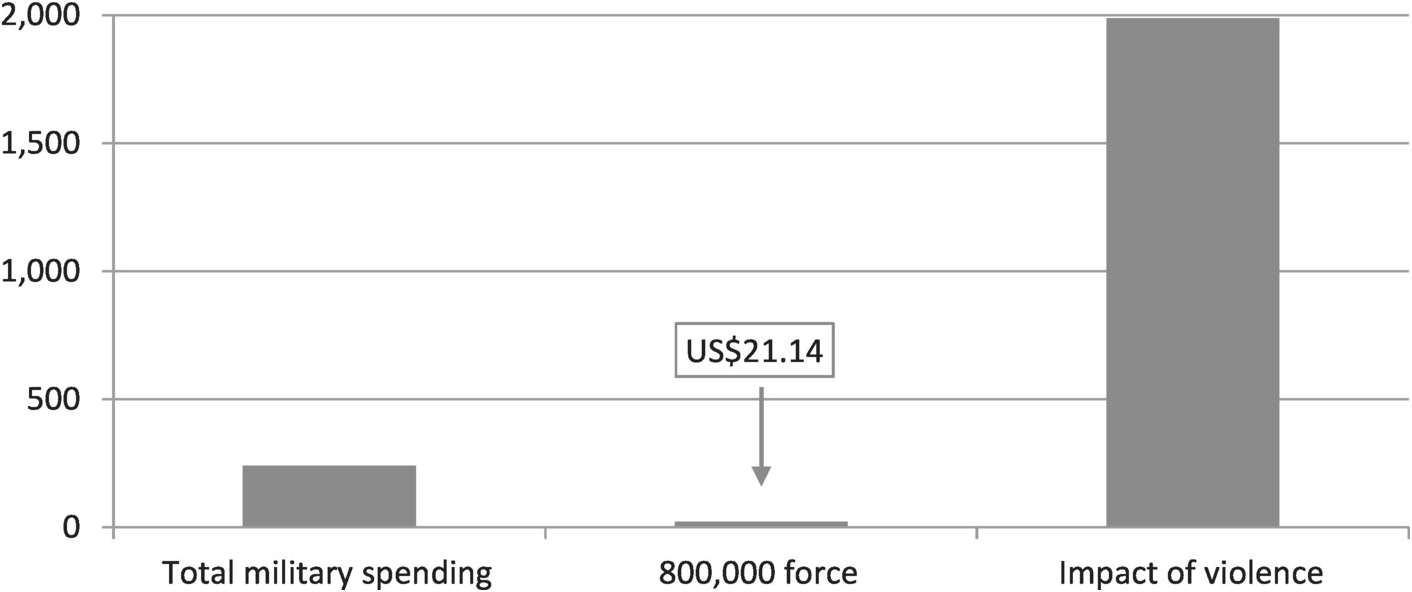

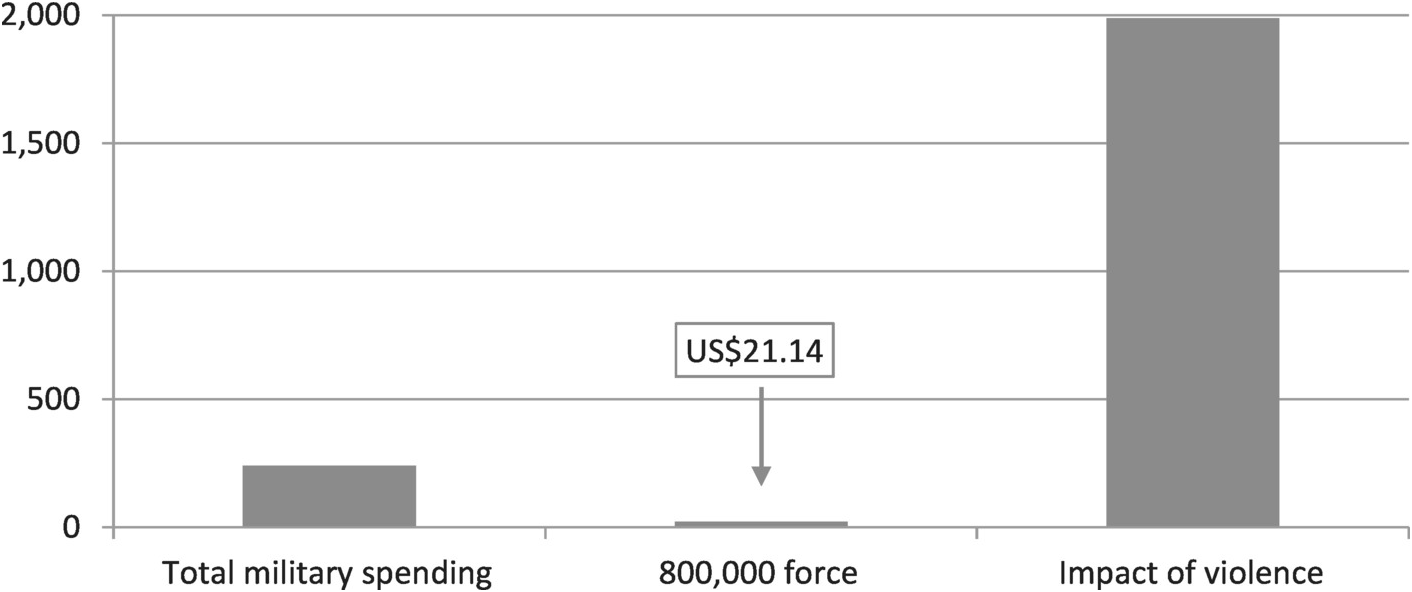

Figure 8.1 Military spending under an international Peace Force (US$ per person per year)

The Establishment of an International Peace Force

Our proposal envisages the creation of an International Peace Force, deriving its ultimate authority from the reformed General Assembly via the Executive Council. As noted earlier, “Security Forces” to be in a state of readiness and available to the UN Security Council for Chapter VII action were envisioned in the Charter through the negotiation of agreements “as soon as possible,” as stipulated in Article 43(3); these agreements were never concluded. Clear terms for the establishment of a new standing force or forces, with parameters of readiness and operation, would at last implement a mechanism envisioned in the current Charter system.

The existence of such a Force does not preclude the presence of national forces necessary to maintain order within national territories, but it does make available to the United Nations effective means for “the prevention and removal of threats to the peace, for the suppression of acts of aggression or other breaches of the peace, and for ensuring compliance with the revised Charter and the laws and regulations enacted thereunder.”Footnote 50 This Force would consist of two components, a Standing Force and a Peace Force Reserve, both composed of volunteers. The Standing Force would be a full-time force of professionals numbering between 600,000 and 1,200,000 as determined by the General Assembly. Under plausible assumptions about salary costs for soldiers, support personnel and weapons systems for an internationally recruited force consisting of 800,000 soldiers, the cost would be roughly US$150 billion per year, or about US$21 per person on the planet per year, compared to US$234 in the current system (see Chart).Footnote 51

To establish the legal basis for the creation of an International Peace Force a number of amendments to UN Charter Chapters VI and VII articles would be necessary. Grenville Clark and Louis Sohn in World Peace through World Law proposed several revisions to the Charter to make this possible. Our discussion here does not provide by any means as comprehensive a treatment of the underlying issues as that undertaken by Clark and Sohn, albeit at a different time in international history. Our intent here is twofold: first, to highlight some (but not all) of the key changes to the Charter that would be necessary to empower the UN in the area of peace enforcement; and, second, to identify some of the more practical considerations that would need to be borne in mind in respect of the creation of such a Peace Force and to make it operational.Footnote 52

One major limitation of the present Charter, in terms of establishing a genuine peace and security system, is the absence of enforcement mechanisms and clear procedural requirements for the international obligation of all states to settle their disputes peacefully, and the lack of compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ (see Chapter 10 on strengthening the international rule of law). Regardless of how intensely a particular dispute endangers the peace of the world, there is no provision in the Charter or the Statute of the International Court of Justice, which would practically oblige the parties, on a universal basis, to submit to peaceful settlement, including a judicial determination. As proposed in Chapter 10, a key revision to the Charter would establish the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ and would require all member nations, as appropriate, to submit international disputes that were amenable to solution through the application of legal principles to a final and binding decision by the ICJ.Footnote 53 Article 94 of the current Charter on the enforcement of decisions of the ICJ should also be strengthened to clarify that, for example, diplomatic and economic sanctions would be available under a revised Article 41 but also, as a last resort, military sanctions through the International Peace Force under a revised Article 42. The combination of the legal authority granted to the General Assembly or the Executive Council if authorized by the Assembly to direct the:

submission of legal questions for final adjudication by the International Court of Justice, together with provisions for the enforcement of the Court’s judgements, would definitely establish the principle of compulsory jurisdiction in respect of all legal issues substantially affecting international peace, and would constitute a great step forward in the acceptance of the rule of law between nations.Footnote 54

It is useful to present here, by way of illustration, the UN Charter’s version of Article 42 and what this Article might look like in a revised Charter that granted the General Assembly the authority for military interventions to secure the peace:

Article 42 – UN Charter: Should the Security Council consider that measures provided for in Article 41 would be inadequate or have proved to be inadequate, it may take such action by air, sea, or land forces as may be necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security. Such action may include demonstrations, blockade, and other operations by air, sea, or land forces of Members of the United Nations.Footnote 55

Article 42 – Revised UN Charter: 1. Should the General Assembly, or the Executive Council if authorized by the Assembly, consider that measures provided for in Article 41 would be inadequate or have proved to be inadequate, it shall direct such action by air, sea, or land elements of the International Peace Force as may be necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security or to ensure compliance with this Charter and the laws and regulations enacted thereunder. Such action may include demonstrations, blockade, and other operations; but any such action shall be taken pursuant to the procedures and subject to the limitations contained in the terms of reference of the International Peace Force. 2. In cases in which the United Nations has directed action by the International Peace Force, all the member Nations shall, within the limitations and pursuant to the procedures governing its deployment, make available to the United Nations such assistance and facilities, including rights of passage, as the United Nations may call for.

The significance of this revision – which is largely drawn from Clark and Sohn – is obvious. The United Nations would no longer depend on the willingness of its members to contribute military forces but would have its own Peace Force, ready to be deployed by the General Assembly (or the Executive Council if authorized by the Assembly, consistent with the provisions for qualified majorities specified for important decisions – see Chapter 7) to restore international peace. The revised Article makes reference to an Annex (to be an integral part of the Charter), which lays out the procedures and other arrangements that have a bearing on how the Peace Force can be utilized and under what limitations and parameters. The revised Article changes the wording of the original from “may take such action” to “shall direct such action” with a view to strengthening the authority of the General Assembly in the area of military sanctions. Or, as noted by Clark and Sohn, “the conception is that, if the Assembly (or the Council) has reached a decision that measures short of armed force are or would be inadequate, it should be required to employ the United Nations Peace Force, since otherwise the United Nations would have to confess impotence to maintain peace.”Footnote 56 This revised Article 42 would need to be read in conjunction with a revised Article 11 on the General Assembly’s new functions and powers.

Furthermore, Article 43, which has turned out to be a highly inadequate provision to ensure a functional collective security system, relying, as it does on voluntary agreements between nations to make available to the UN military forces, could be amended in conjunction with the Annex on Peace Force arrangements, so that the United Nations would have adequate means even in extreme emergencies, subject to appropriate safeguards, to maintain or restore peace and to enforce compliance with respect to the revised Charter. This could be done by allowing the maximum limits on the sizes of the standing component and the Peace Force Reserve to be exceeded for a limited period of time.

Beyond the amendments to the Charter that would be necessary to provide the legal basis for UN military actions to secure the peace, it will be necessary as well to lay out the various practical issues that would underpin the establishment and the operations of the Peace Force. The nonexhaustive list in the following box, includes various provisions for the operation of this force, as a starting point for further elaboration. In this list we have drawn from Clark and Sohn’s work, who gave a great deal of thought to such operational concerns which they perceived as important at the time of their writing.

Box: The International Peace Force: Selected Operational Considerations

Objectives

1 In the recruitment and organization of the International Peace Force, the objective will be to create and maintain a highly trained professional force such that it is fully capable of safeguarding international peace.

2 The International Peace Force will never be employed to achieve objectives inconsistent with the Purposes and Principles of the (revised) Charter.

Recruitment and Staffing (Personnel)

3 The members of the International Peace Force and its civilian employees, together with their dependents, will be entitled to all the privileges and immunities provided to UN personnel.

4 The Executive Council will appoint the first members of the Military Staff Committee. The terms of office of these initial members will begin on the same day and expire, as designated by the Council at the time of their appointment, one at the end of one year, one at the end of two years, one at the end of three years, one at the end of four years and one at the end of five years from that date. Later appointments will be for equal term lengths – to be determined from time to time by the Council, but never to exceed five years.Footnote 57

5 The Military Staff Committee will prepare for the recruitment and training of both components and will organize the necessary administrative staff.

6 International Peace Force members will be recruited wholly by voluntary enlistment. The General Assembly will have no power to enact a compulsory draft law; and no nation may apply any sort of compulsion to require enlistment in the Peace Force, except under the exceptional circumstances described in Article 43 of the (revised) Charter and subject to the limitations in paragraph 35 below.

7 The members will be selected through international recruitment under the supervision of the Military Staff Committee based on their competence, integrity and devotion to the purposes of the United Nations, and will receive training on the high purpose of their mission and the ethical principles that should guide all their actions. With the exception of commanders at all levels, they must not be more than 35 years old at the time of initial enlistment.

8 The members will declare loyalty to the United Nations in a form prescribed by the General Assembly. They will be restricted from seeking or receiving instructions from any government or authority external to the United Nations. They will refrain from any conduct that might reflect poorly on their position as members of the Peace Force.

9 The term of service of members of the standing component of the Peace Force will be between four and eight years, determined by the General Assembly.Footnote 58

10 The term of service of Reserve members will be between six and ten years, also determined by the General Assembly. They will receive basic training for between four and eight months during the first three years of their term, and again during the remainder of their term, as determined by the Assembly in consultation with the Military Staff Committee.

11 The Force’s officers will be selected, trained, promoted, and retired with a view to create a peerless officer corps. Opportunities for promotion to officer positions will be provided to highly qualified men and women from the rank and file.

12 The members of both components of the Peace Force will be recruited on as wide a geographical basis as possible, subject, except in extreme emergency (see paragraph 36), to the following limitations:

a. The number of nationals of any nation serving at any one time in either component of the Peace Force cannot exceed 5 percent of the total enlistment of that component.

b. The number of nationals of any nation serving at any one time in any of the three main branches of either component (land, sea and air) cannot exceed 5 percent of the total enlistment of that branch.

c. The number of nationals of any nation serving at any one time in the officer corps of one of the three main branches of either component cannot exceed 5 percent of the officer corps for that branch.Footnote 59

13. Units of the Peace Force will be composed to the greatest possible extent of different nationalities. No unit exceeding one hundred in number can be composed of nationals of a single nation.

14. The Peace Force will, to the extent authorized by the General Assembly, employ civilian personnel for the services and functions that do not need to be performed by military personnel; civilian personnel will not be deemed members of the Peace Force.

15 After being honorably discharged from the standing component of the Peace Force following at least two full enlistment periods, a member and their dependents will be entitled to choose the nation in which they wish to live, and they will be entitled to acquire the nationality of that nation if they are not already nationals.

Administration

16. The General Assembly will adopt the basic laws necessary to provide for the organization, administration, recruitment, training, equipment, and deployment of the Peace Force’s Standing and Reserve components.

17. The General Assembly will have authority to amend and enact the basic laws and regulations referenced in paragraph 16, and those deemed necessary for the organization, administration, recruitment, discipline, training, equipment, and deployment of the Peace Force.

18. If the General Assembly determines that the economic measures provided for in Article 41 of the (revised) Charter are inadequate or have proved to be inadequate to maintain or restore international peace or to ensure compliance with the (revised) Charter, and that the Peace Force has not reached sufficient strength to deal with the situation, the Assembly will direct such action by part or all of the national forces which have been designated in paragraph 35 as it deems necessary. This action will be taken within the limitations established in paragraphs 27–32.

19. The General Assembly will have authority to enact the laws and regulations deemed necessary for the strategic direction, command, organization, administration, and deployment of the national forces designated in paragraph 34 when action by any such national forces has been directed pursuant to paragraph 18.

20. The Military Staff Committee will have direct control of the Peace Force. The Executive Council may issue instructions to the Committee as it deems fit.