Corruption kills … The money stolen through corruption every year is enough to feed the world’s hungry 80 times over … Corruption denies them their right to food, and, in some cases, their right to life.Footnote 1

The successful prosecution and imprisonment of corrupt leaders would create opportunities for the democratic process to produce successors dedicated to serving their people rather than to enriching themselves.Footnote 2

If the purpose of governance is to execute collective functions in the common interest, its essential foundation is trust in the institutions of government and confidence that the functions will be carried out justly and effectively. Corruption is the antithesis of this, turning institutions against their intended purpose, plundering the resources available, undermining confidence in government and destroying human prosperity. While previously underappreciated for its widespread and insidious effects, corruption has finally emerged as a problem involving enormous social and economic costs – no approach to governance today can avoid addressing it head on.

The pernicious and systemic ramifications of corruption have now been well documented, with corrupt officials often being the worst human rights abusers and even linked to war crimes. Economically speaking, it is estimated that trillions of dollars in bribes are paid globally on an annual basis, with more than 5 percent of global GDP likely being lost to all forms of corruption every year.Footnote 3 Moreover, as has been powerfully argued in recent analyses, the international security consequences of endemic corruption in various states are ignored at our own peril.Footnote 4 As expressed by then US Secretary of State John Kerry, “the quality of governance is no longer just a domestic concern.”Footnote 5

It has also been argued recently that the key to economic prosperity, across societies, is the creation and maintenance of “inclusive” economic and political institutions, rather than those engineered in the service of ruling elites bent on extractive behaviors.Footnote 6 Acemoglu and Robinson argue that it is only through inclusive and fair institutions that conditions for collective prosperity are achieved, as such institutions, among other things, provide the appropriate incentives to reward the innovation and hard work required to drive economic development.

In the first part of this chapter we provide a broad definition of corruption and discuss why it is so toxic to effective governance. We then address how corruption has emerged as a key issue in the development process after being ignored for many decades. We explore the ways that, without proper vigilance, government and corruption can become intertwined and feed off each other, destroying the foundations of human prosperity and the very purpose of governance. We review existing efforts to tackle corruption at the national, regional and global levels, and suggest additional ways forward. Finally, we support proposals for the establishment of an International Anticorruption Court (IACC), to greatly strengthen and better implement a range of legal instruments that are already in place, but that have had limited success in arresting the growth of multiple forms of corruption across the planet – affecting developing and developed countries alike. We consider the setting up of an IACC as a necessary adjunct to existing tools to check the spread of what many now regard as a global epidemic.

Defining Corruption

Corruption is traditionally defined as the abuse of public office for private gain, including bribery, nepotism and misappropriation; extra-legal efforts by individuals or groups to gain influence over the actions of the bureaucracy; the collusion between parties in the public and private sectors for the benefit of the latter; and more generally influencing the shaping of policies and institutions in ways that benefit the contributing private parties at the expense of the broader public welfare.Footnote 7 The benefits are customarily seen as financial, and many people become rich through corruption.

However, the corruption that is eating into the vitals of global society today is more than just the material corruption of bribery, extortion or embezzlement for personal gain. It is any undue preference given to personal or private gain at the expense of the public or collective interest, including the betrayal of a public trust or office in government, but also the manipulation of a corporate responsibility for self-enrichment, the distortion of truth and denial of science to manipulate the public for ideological ends, and even the misuse of a religious responsibility to acquire power and wealth. Corruption is just one expression of the priority given to oneself over others, of egoism over altruism, of personal over collective benefit.Footnote 8 It is often said that power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. One of the first effects of corruption in government is to reduce the capacity of a public administration to fight corruption, creating a vicious circle from which a government has difficulty extricating itself. Corruption at the governmental level is now so widespread that it is an obvious area for international governance to set standards and intervene in the common interest.

A related issue is organized crime, which exists largely through collusion with governments. This can take the form of turning a blind eye to criminal behavior, perhaps for kickbacks or other advantages, directing government procurement or other contracts to criminal enterprises in return for a share of inflated contracts, and interfering with the course of justice to the benefit of criminals. There is potential for such corruption at all levels, from the individual police officer who rents a gun to robbers at night, to heads of state who accept large cash donations in return for favors. Where governments are incorruptible and prosecute criminal activity with vigor, organized crime has difficulty gaining a foothold.

Corruption and associated organized crime are not just a marginal issue. The illegal economy from organized crime is now estimated at US$2 trillion per year, roughly equivalent to all the world’s defense budgets. Bribery has been estimated to amount to US$1 trillion,Footnote 9 with the vast majority of bribes going to people in wealthy countries. Ten percent of all public health budgets are lost to corruption.Footnote 10 Much of this money escapes from national control and oversight along with many international financial flows, as another negative dimension of globalization.

The impacts of corruption are not limited to financial losses and diversions or political inefficiency or failures. If leaders are corrupt, others will be inspired to follow the same model. There are many secondary effects of corruption that spread throughout society. For example, the impact of corruption on environmental destruction and mismanagement is often underestimated because, as an illegal activity, it escapes from statistics; yet it is a principal reason for the failure of many efforts at environmental protection and management, whether from traffic in endangered species, illegal logging and fishing, or ignoring or evading environmental regulations. Both the public and private sectors are heavily implicated in this form of corruption, as is organized crime.

Normally it is a government’s responsibility to prohibit, investigate and prosecute corrupt behavior within its borders or for which its nationals are responsible. However, there are frequently cases where the highest levels of government are themselves corrupt, or where corruption has become so widespread that it is seen as a normal and legitimate part of politics and simply a cost of doing business.Footnote 11 In many cases, the police and courts that should be investigating and prosecuting corrupt behavior are themselves caught up in the system. Criminal prosecutions may then simply become an instrument for eliminating political opponents. Guarantees of immunity from prosecution are another tool used by the corrupt for their own protection. In such situations, national sovereignty becomes a shield behind which to hide illegal activity from international scrutiny.

It is not unknown for a government motivated by corrupt intentions to use legislation or judicial interpretation to render legal those practices that in other states or contexts would be considered corrupt and illegal. For example, removing all limits to the amount of money that individuals or corporate enterprises can donate to the campaign funds of politicians essentially amounts to vote-buying, with politicians becoming dependent on and beholden to the highest bidder.

Only international standards of honesty and definitions of corruption with appropriate means of enforcement will make it possible to intervene in the general public interest where a government has opened the door to corrupt behavior at the expense of its own people. To prevent the rot from spreading, and to protect the public who ultimately pay the price for such corruption, global standards and mechanisms for international intervention are essential.

Corruption Within the Development Process

After many years of authorities turning a blind eye, corruption has finally emerged as a central issue in discussions about the effectiveness of development policies. It is now recognized that corruption comes from many sources and undermines the development process in multiple ways. While various remedies have been proposed and are being used in various parts of the world, the results are mixed.

The period since the late 1990s has witnessed a remarkable change in the understanding of what factors matter in creating the conditions for sustainable economic development. The economics profession has come to a new comprehension of the role of such factors as education and skills, institutions, property rights, technology, transparency and accountability. With this broader outlook has come an implicit recognition that promoting inclusive growth requires tackling an expanding set of nontraditional concerns.

One of these concerns is corruption, a subject that has gone from being very much on the sidelines of economic research to becoming a central preoccupation of the development community and of policy-makers in many countries. Experiences and insights accumulated during the postwar period, and reflected in a growing body of academic research, throw light on the causes and consequences of corruption within the development process and on the question of what can be done about it.

Within the development community, the shift in thinking about the role of corruption in development was tentative at first; multilateral organizations remained reluctant to touch on a subject seen as largely political even as they made increasing references to the importance of “good governance” in encouraging successful development. What factors contributed to this shift? One was linked to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the associated collapse in the late 1980s of central planning as a supposedly viable alternative to free markets. As the international community faced the need to assist formerly socialist countries in making a successful transition to democratic forms of governance and market-based economies, it was clear that this would take far more than “getting inflation right” or reducing the budget deficit. Central planning had collapsed not because of inappropriate fiscal and monetary policies but because of widespread institutional failings, including a lethal mix of authoritarianism (with its lack of accountability) and corruption. Overnight, the economics profession was forced to confront a set of issues extending far beyond conventional macroeconomic policy.

Related to the demise of central planning, the end of the Cold War had clear implications for the willingness of the international community to recognize glaring instances of corruption in places where ideological loyalties had earlier led to collective blindness. By the late 1980s, the donor community cut off President Mobutu of (then) Zaire, for instance, no longer willing to quietly reward him for his loyalty to the West during the Cold War.

A second factor was growing frustration with entrenched patterns of poverty in Africa in particular, as well as in other parts of the developing world. The global fight against poverty had begun to produce gains, but these were concentrated largely in China; in Africa, the number of so-called extremely poor people was actually increasing.Footnote 12 During the late 1980s and early 1990s, staff at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) began to look beyond macroeconomic stabilization to issues of structural and institutional reform. Corruption could no longer be ignored.

A third factor had to do with developments in the academic community. Research began to suggest that differences in institutions appeared to explain an important share of the differences in growth between countries. An increasing number of economists began to see corruption as an economic issue, and this led to a better understanding of its economic effects.

An important role was also played by the intensifying pace of globalization beginning in the 1980s. Globalization and its supporting technologies have led to a remarkable increase in transparency as well as to growing public demand for greater openness and scrutiny. The multilateral organizations were not immune to these influences. How could one overlook the hoarding of billions of dollars of ill-gotten wealth in secret bank accounts by the world’s worst autocrats, many of them long-standing clients of these organizations?

Paralleling these developments, and further raising international public awareness of corruption, were the many corruption scandals in the 1990s involving major political figures. In India and Pakistan, incumbent prime ministers were defeated in elections largely because of corruption charges. In South Korea, two presidents were jailed following disclosures of bribery. In Brazil and Venezuela, bribery charges resulted in presidents being impeached and removed from office. In Italy, magistrates sent to jail a not insignificant number of politicians who had ruled the country in the postwar period, exposing the vast web of bribery that had bound together political parties and members of the business community. In Africa, there was less progress in holding leaders to account, but corruption became harder to hide as new communication technologies supported greater openness and transparency.

Globalization also highlighted the importance of efficiency. Countries could not hope to continue to compete in the increasingly complex global market unless they used scarce resources effectively. And rampant corruption detracted from the ability to do this. Meanwhile, business leaders began to speak more forcefully about the need for a level playing field and the costs of doing business in corruption-ridden environments.

In the 1990s, the US government made efforts to keep the issue of corruption alive in its discussions with OECD partners, further raising international awareness. The US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 had forbidden American executives and corporations to bribe foreign government officials, introducing stiff penalties, including prison terms, for those doing so. Because other OECD countries did not impose such restrictions – in fact, most continued to allow tax deductions for bribe payments, as a cost of doing business abroad – American companies began to complain that they were losing business to OECD competitors. Academics sifting through the data showed that US business activity abroad declined substantially following passage of the law. These developments gave impetus to US government efforts to persuade other OECD members to ban bribery practices, and in 1997 the OECD adopted the Anti-Bribery Convention, an important legal achievement.

Another factor contributing to this shift in attitude was the work of Transparency International, including the publication, beginning in 1993, of its Corruption Perceptions Index. That corruption existed everywhere was a well-known fact. What Transparency International showed was that some countries had been more successful than others in curtailing it. The organization’s work helped to focus public attention on corruption and legitimize public discourse on the issue, easing the transition of the multilateral organizations into doing the same.

Transparency International was soon assisted in its efforts by the international organizations themselves. In a speech at the IMF–World Bank annual meeting in 1996, then World Bank President James Wolfensohn did not mince words, saying that there was a collective responsibility to deal with “the cancer of corruption.” More importantly, Wolfensohn gave strong backing to efforts by Bank staff to develop a broad range of governance indicators, including indicators specifically capturing the extent of corruption. This made it possible for the Bank, through the use of quantified indicators and data, to focus attention on issues of governance and corruption while not appearing to interfere in the political affairs of its member countries.

Poor Government and Corruption: Intimate Bedfellows?

What are the sources of corruption, and what factors have nourished it and turned it into such a powerful impediment to sustainable economic development? Economists seem to agree that one important source of corruption stems from the distributional attributes of the state.

For better or for worse, the role of the state in the economy has greatly expanded over the past century. In 1913, the world’s 13 largest economies had public expenditure averaging around 12 percent of GDP. By 1990, this ratio had risen to 43 percent, and in some of these countries to well over 50 percent. Many other countries saw similar increases. Associated with this growth was a proliferation of benefits under state control and also of the ways in which the state imposes costs on society. A larger state need not be associated with higher levels of corruption – the Nordic countries illustrate this. The benefits range from improved infrastructure, public education, health and welfare, to environmental protection and reining in the monopolistic tendencies of corporations. It is not the size of government itself that is the problem. But the larger the number of interactions between officials and private citizens and the weaker the ethical framework determining socially acceptable behavior, the more opportunities there are for citizens to pay illegally for benefits to which they are not entitled or to avoid costs or obligations for which they are responsible.

From the cradle to the grave, the typical citizen has to enter into transactions with government offices or bureaucrats for countless reasons – to obtain a birth certificate, get a passport, pay taxes, open a new business, drive a car, register property, engage in foreign trade. Indeed, governing often translates into issuing licenses and permits to individuals and businesses complying with regulations in myriad areas. The World Bank’s Doing Business report, a useful annual compendium of the burdens of business regulations in 190 countries, paints a sobering picture. Businesses in many parts of the world endure numbing levels of bureaucracy and red tape. In fact, the data in the report eloquently portray the extent to which many governments discourage the development of entrepreneurship in the private sector.

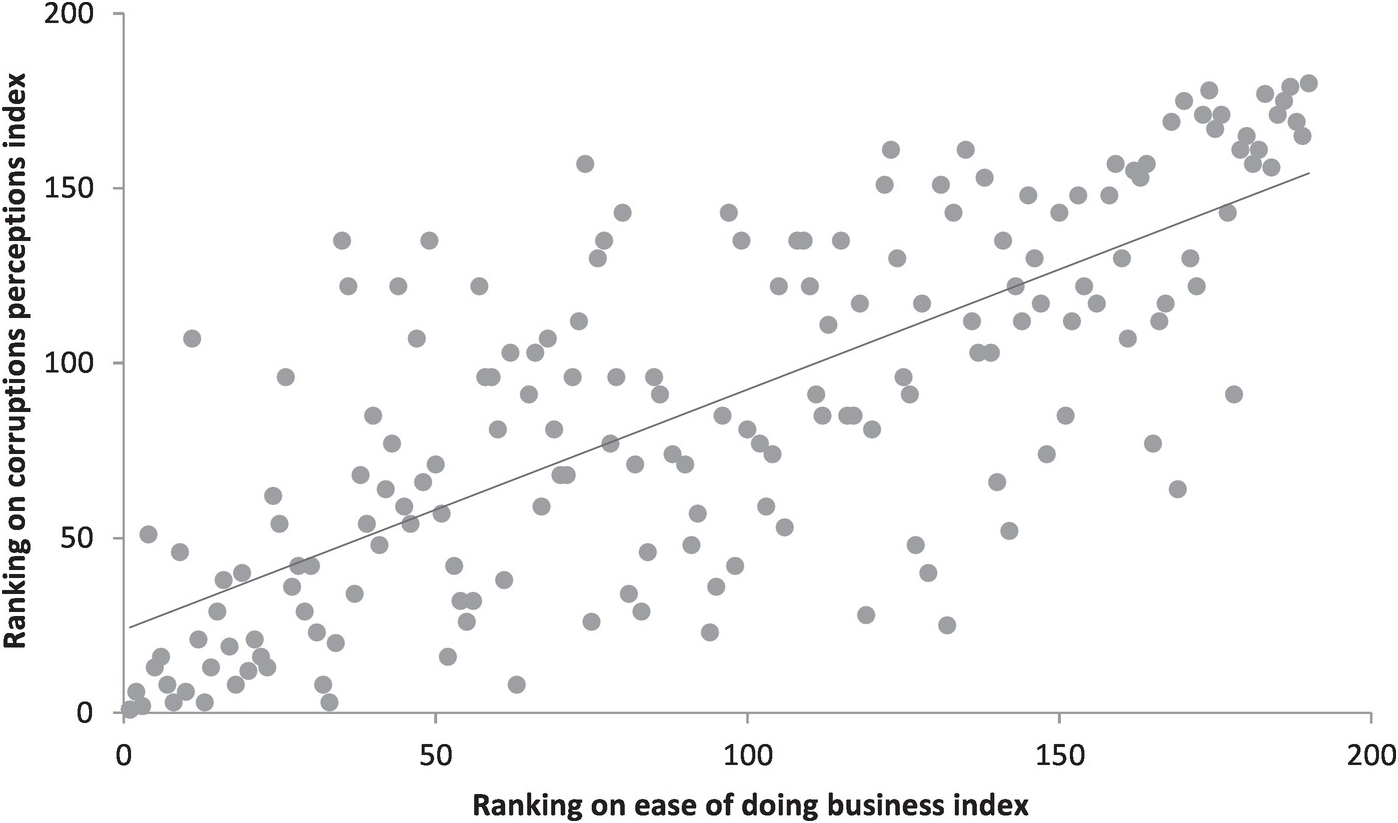

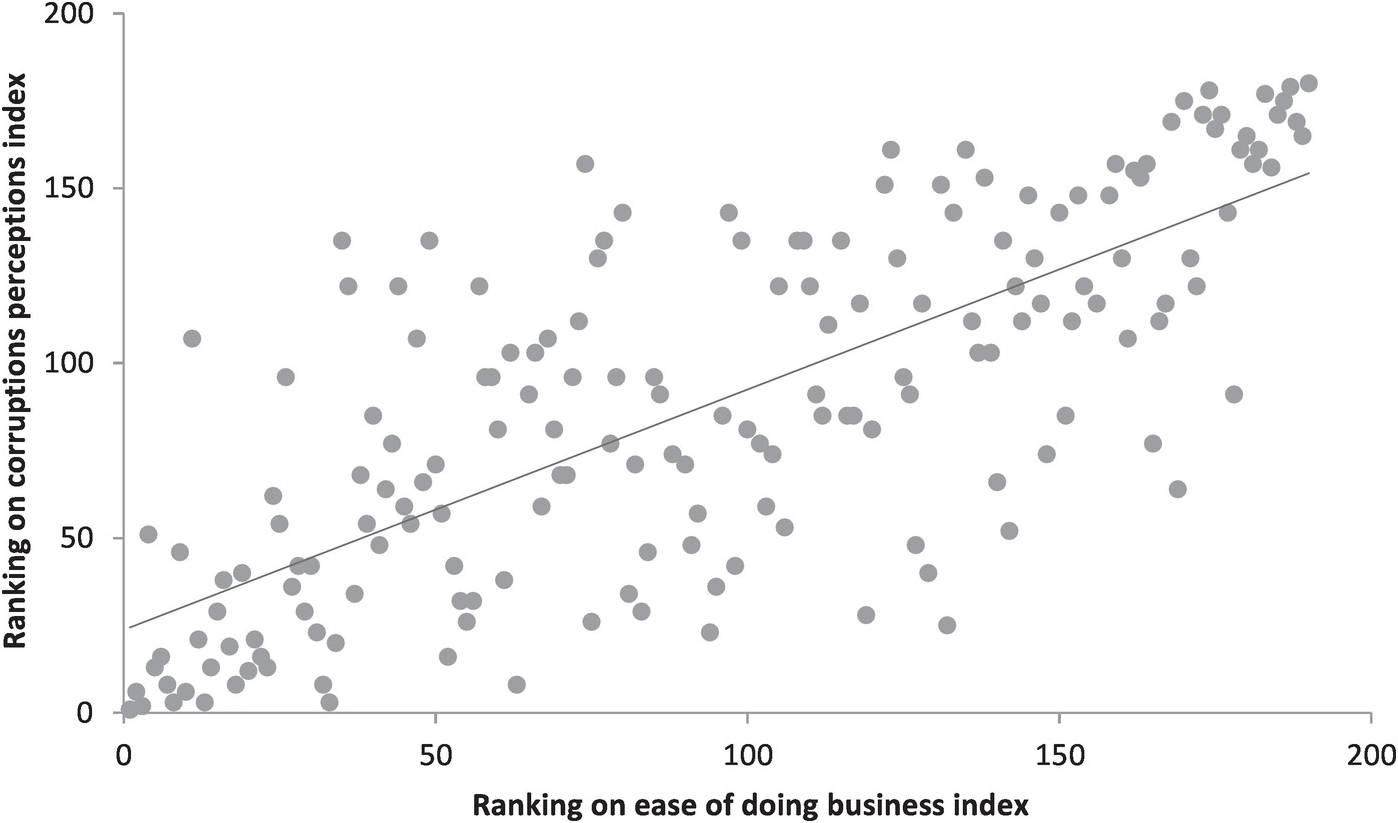

Not surprisingly, the prevalence of corruption is strongly correlated with the incidence of red tape and cumbersome, excessive regulation, which is not generally linked to the public interest. Figure 18.1 compares the rankings of 177 countries on Transparency International’s 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index with their rankings on the Doing Business report’s Ease of Doing Business Index for the same year. The figure speaks for itself: the greater the extent of bureaucracy and red tape, the greater the incidence of corruption – the correlation coefficient is close to 0.80.

Figure 18.1. Rankings of 177 countries on the Corruption Perceptions Index and Ease of Doing Business Index, 2018.

As many surveys have shown, businesses allocate considerable time and resources to dealing with unnecessary bureaucracy. They may often perceive paying bribes as a way to save time and enhance efficiency – and, in many countries, as possibly the only way to get business done without undermining their competitive position relative to those that routinely pay bribes. The more dysfunctional the economic and legal system and the more onerous and ill-conceived the regulations, the greater the incentives to short-circuit the system by paying bribes. The literature is full of examples: the absurdities of central planning in the Soviet Union induced “corruption” on the part of factory managers, to add some flexibility to a system that made a mockery of efficiency in resource allocation. The more irrational the rules, the more likely that participants in the system will find themselves breaking them.

In an insightful analysis in 1964, the Harvard researcher Nathaniel Leff argued that those who viewed corruption as an unremittingly bad thing were implicitly assuming that governments were driven by benevolent motivations and committed to implementing policies that advanced the cause of economic development. In reality, Leff thought, policies in many countries were geared largely to advancing the interests of the ruling elite. Leff and his Harvard colleague Joseph Nye both suggested that corruption was partly a response to market distortions, red tape, excessive and unreasonable regulation and bad policies, but that these were themselves affected by the prevailing levels of corruption – in a symbiotic two-way form of causality that turned corruption into an intractable social and economic problem.Footnote 13

Features of government organization and policy may (wittingly or unwittingly) create incentives for corrupt behavior in numerous ways. The tax system is often a source of corruption, particularly where tax laws are unclear or otherwise difficult to understand. This lack of clarity presumably gives tax inspectors and auditors considerable leeway in interpretation, allowing unwholesome “compromises” with taxpayers. The provision of goods and services at below-market prices also creates fertile ground for corruption. It invariably gives rise to some form of rationing mechanism to manage excess demand, requiring the exercise of discretion by government officials. At a meeting at the Central Bank of Russia in May 1992, IMF staff were shown a several-page list of the exchange rates that applied for importing items, from medications and baby carriages to luxury cars. Bureaucrats had managed to come up with criteria for establishing dozens of different prices for foreign exchange. Needless to say, the list allowed considerable latitude for discretion.

A similar regime existed for export quotas, allowing those who obtained an export license to benefit from the huge gap between the domestic and international price. Another legacy of the Soviet Union was a system of directed credits, essentially highly subsidized loans to agriculture and industry. At rates of interest that were absurdly negative in real terms, these credits were in strong demand and, of course, the criteria for allocating them were extremely opaque.

The incentives for bribes provided in these examples are easy to see; the resulting losses in economic efficiency are similarly evident. Directed credits in Russia did not generally end up with farmers. Instead, they ended up with the highest bidder, who then used the proceeds to buy foreign exchange and finance capital flight (while never repaying the credits or doing so only in deeply depreciated rubles). Export quotas resulted in massive losses for the Russian budget, at a time when the country was going through a severe economic contraction and there were therefore enormous pressures for increased social spending. Susan Rose-Ackerman, one of the leading experts on corruption, refers to the kinds of bribes in these examples as those that clear the market or that equate supply and demand.

Some bribes are offered as incentive payments for bureaucrats. These can take a variety of forms. One is “speed money,” ubiquitous in many parts of the world and typically used to “facilitate” some transaction or to jump the queue. Some economists have argued that this kind of bribery could improve efficiency, since it provides incentives to work more quickly and allows those who value their time highly to move faster. Gunnar Myrdal, writing in 1968, pointed out that, over time, incentives could work the other way: bureaucrats may deliberately slow things down or, worse, find imaginary obstacles or create new ones in order to attract facilitation fees. So, in the end, “speed money” is paid not to speed things up but to avoid artificial delays created by corrupt bureaucrats.

Indeed, some of the regulations enforced in many parts of the world are so devoid of rationality that one can only infer that they were introduced to create opportunities for bribery. Far from being a way to enhance efficiency, paying bribes preserves and strengthens the bribery machinery.

All this is not to say that government regulation is inherently wrong. On the contrary, the World Economic Forum has shown that appropriate environmental and social regulations, fairly enforced, can increase business competitiveness and efficiency in meeting social goals. Where corruption makes it possible to get around the regulations, the result is bad for both business and the public welfare.Footnote 14

Nine Reasons Why Corruption Is a Destroyer of Prosperity

No matter its source, corruption damages the social and institutional fabric of a country in ways that undermine sustainable economic development. A review of some of its consequences helps show why corruption destroys human prosperity.

First, corruption undermines government revenue and therefore limits the ability of the government to invest in productivity-enhancing areas. Where corruption is endemic, people will view paying taxes as a questionable business proposition. There is a delicate tension between the government as tax collector and businesses and individuals as taxpayers. The system works reasonably well when those who pay taxes feel that there is a good chance they will see a future payoff, such as better schools, better infrastructure and a better-trained and healthier workforce. Corruption sabotages this implicit contract.

When corruption is allowed to flourish, taxpayers will feel justified in finding ways to avoid paying taxes or, worse, become bribers themselves. To the extent that corruption undermines revenue, it undermines government efforts to reduce poverty. Money that leaks out of the budget because of corruption will not be available to lighten the burden of vulnerable populations. Of course, corruption also undermines the case of those who argue that foreign aid can be an important element of the fight against global poverty – why should taxpayers in richer countries be asked to support the lavish lifestyles of the kleptocrats in corrupt states?

Second, corruption distorts the decision-making process connected with public investment projects, as the IMF economists Vito Tanzi and Hamid Davoodi demonstrated in a 1997 analysis. Large capital projects provide tempting opportunities for corruption. Governments will often undertake projects of a greater scope or complexity than is warranted by their country’s needs – the world is littered with the skeletons of white elephants, many built with external credits. Where resources are scarce, governments will find it necessary to cut spending elsewhere. Tanzi plausibly argued in 1998 that corruption will also reduce expenditure on health and education, because these are areas where it may be more difficult to collect bribes.

Third, there is solid empirical evidence that the higher the level of corruption in a country, the larger the share of its economic activity that will go underground, beyond the reach of the tax authorities. Not surprisingly, studies have shown that corruption also undermines foreign direct investment, because it acts in ways that are indistinguishable from a tax; other things being equal, investors will always prefer to establish themselves in less corrupt countries. Shang-Jin Wei, in a 2000 analysis of data on direct investment from 14 source countries to 45 host countries, concluded that “an increase in the corruption level from that of Singapore to that of Mexico is equivalent to raising the tax rate by 21–24 percentage points.”

Fourth, corruption discourages private sector development and innovation and encourages various forms of inefficiency. Budding entrepreneurs with bright ideas will be intimidated by the bureaucratic obstacles, financial costs and psychological burdens of starting new business ventures and may opt to take their ideas to some other, less corrupt country or, more likely, desist altogether. Thus, whether corruption is a barrier to entry into the market or a factor in precipitating early departure, it harms economic growth.

A high incidence of corruption will also mean an additional financial burden on businesses, undermining their international competitiveness. Unlike a tax, which is known and predictable and can be built into a company’s cost structure, bribes are unpredictable and will complicate cost control, reduce profits and undermine the efficiency of companies that must pay them to stay in business. In a 1995 analysis using indices of corruption and institutional efficiency, the IMF economist Paulo Mauro showed that corruption lowers investment and thus economic growth.

Fifth, corruption contributes to a misallocation of human resources. To sustain a system of corruption, officials and those who pay them will have to invest time and effort in developing certain skills, nurturing certain relationships and building up a range of supporting institutions and opaque systems, such as secret bank accounts and off-the-books transactions. Surveys of businesses have shown that the greater the incidence of corruption in a country, the greater the share of time that management has to allocate to ensuring compliance with regulations, avoiding penalties and dealing with the bribery system that underpins them – activities that draw attention and resources away from more productive tasks.

Sixth, corruption has disturbing distributional implications. In empirical work done at the IMF in 1998, Gupta, Davoodi and Alonso-Terme showed that corruption, by lowering economic growth, perceptibly pushes up income inequality. It also distorts the tax system, because the wealthy and powerful are able to use their connections to ensure that this system works in their favor. And it leads to inefficient targeting of social programs, many of which will acquire regressive features, with benefits disproportionately allocated to the higher income brackets – as with gasoline subsidies to the car-owning middle classes in India and dozens of other countries.

Seventh, corruption creates uncertainty. There are no enforceable property rights emanating from a transaction involving bribery. A firm that obtains a concession from a bureaucrat as a result of bribery cannot know with certainty how long the benefit will last. The terms of the “contract” may have to be constantly renegotiated to extend the life of the benefit or to prevent its collapse. Indeed, the firm, having flouted the law, may fall prey to extortion from which it may prove difficult to extricate itself. In an uncertain environment with insecure property rights, firms will be less willing to invest and plan for the longer term. A short-term focus to maximize short-term profits will be the optimal strategy, even if this leads to deforestation, say, or to the rapid exhaustion of non-renewable resources.

Very importantly, this uncertainty is partly responsible for a perversion in the incentives that prompt individuals to seek public office. Where corruption is rife, politicians will want to remain in office as long as possible, not because they are even remotely serving the public good but because they will not want to yield to others the pecuniary benefits of high office, and may also wish to continue to enjoy immunity from prosecution. Where long stays in office cease to be an option, a new government, given a relatively short window of opportunity, will want to steal as much as possible as quickly as possible.

Eighth, because corruption is a betrayal of trust, it diminishes the legitimacy of the state and the moral stature of the bureaucracy in the eyes of the population. While efforts will be made to shroud corrupt transactions in secrecy, the details will leak out and will tarnish the reputation of the government. By damaging the government’s credibility, this will limit its ability to become a constructive agent of change in other areas of policy. Corrupt governments will have a more difficult time remaining credible enforcers of contracts and protectors of property rights.

Ninth, bribery and corruption lead to other forms of crime. Because corruption breeds corruption, it tends soon enough to lead to the creation of organized criminal groups that use their financial power to infiltrate legal businesses, to intimidate, and to create protection rackets and a climate of fear and uncertainty. In states with weak institutions, the police may be overwhelmed, reducing the probability that criminals will be caught. This, in turn, encourages more people to become corrupt, further impairing the efficiency of law enforcement – a vicious cycle that will affect the investment climate in noxious ways, further undermining economic growth. In many countries, as corruption gives rise to organized crime, the police and other organs of the state may themselves become criminalized. By then, businesses will not only have to deal with corruption-ridden bureaucracies; they will also be vulnerable to attacks from competitors who will pay the police or tax inspectors to harass and intimidate.

In fact, there is no limit to the extent to which corruption, once unleashed, can undermine the stability of the state and organized society. Tax inspectors will extort businesses; the police will kidnap innocents and demand ransom; the prime minister will demand payoffs to be available for meetings; aid money will disappear into the private offshore bank accounts of senior officials; the head of state will demand that particular taxes be credited directly to a personal account. Investment will come to a standstill, or, worse, capital flight will lead to disinvestment. In countries where corruption becomes intertwined with domestic politics, separate centers of power will emerge to rival the power of the state.

At that point, the chances that the government will be able to do anything to control corruption will disappear and the state will mutate into a kleptocracy, the eighth circle of hell in Dante’s Divine Comedy. Alternatively, the state, to preserve its power, may opt for warfare, engulfing the country in a cycle of violence. And corrupt failed, or failing, states become a security threat for the entire international community – because, as Heineman and Heimann wrote in Foreign Affairs in 2006, “they are incubators of terrorism, the narcotics trade, money laundering, human trafficking, and other global crime – raising issues far beyond corruption itself.”Footnote 15 More recently, Chayes has tracked the regional and international security implications of kleptocracies in such countries as Afghanistan, Egypt and Nigeria, among others, noting the transnational effects of systemic corruption as akin to an “odourless gas” fueling the various identified threats “without attracting much policy attention.”Footnote 16 “When every government function is up for sale to the highest bidder,” she notes, “violations of international as well as domestic law become the norm.”Footnote 17 The sale of Pakistani nuclear technology to Iran, North Korea and Libya is just one dramatic example.

Tackling Corruption

As all of these points demonstrate, corruption is a major impediment to effective governance, transparency, economic development and the proper allocation of public funds for public good, as well as the source of a range of very serious transnational security risks. As corruption in governments and the private sector has globalized, so must the efforts to tackle it. An international legal framework for corruption control is essential to deal with its cross-border effects, and fortunately a strong foundation already exists.

New, well-designed international implementation and enforcement tools should give significantly greater effect to existing international conventions in this field, such as the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC), with 186 parties (entry into force December 2005), and the 1997 OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions, with 43 states parties (entry into force February 1999). In addition to these conventions, there are also a range of regional treaties covering Africa, Europe, and the Americas.

Unlike the OECD convention, the UNCAC creates a global legal framework involving developed and developing nations and covers a broader range of subjects including domestic and foreign corruption, extortion, preventive measures, anti-money-laundering provisions, conflict-of-interest laws and means to recover illicit funds deposited by corrupt officials in offshore banks. As UNCAC only possesses a weak monitoring mechanism, and the implementation of its provisions in effect has been “largely ignored,”Footnote 18 enforcement should be a priority in strengthened international governance. Until such enhanced tools are developed, the effectiveness of the UNCAC as a deterrence tool will very much depend on the establishment of adequate national monitoring mechanisms to assess government compliance. Many countries need technical assistance to develop the capacity to comply with the UNCAC’s provisions. Multinational corporations are both originators of bribery and frequent victims of extortion, and need strong internal controls and sanctions to protect themselves against malfeasance with its resulting damaging revelations and large fines. Additional international legislation may also be required for types of corruption that are insufficiently regulated, and for novel forms of corruption enabled by new technologies.

Others have argued that another workable approach to fighting corruption may be more robust implementation of the anticorruption laws in the 43 states that have signed the OECD’s Anti-Bribery Convention. Governments will need to do better in holding to account companies that continue to bribe foreign officials. They have at times been tempted to shield companies from the need to comply with anticorruption laws, in a misguided attempt to avoid undermining their competitive position in other countries. Trade promotion should not be seen to trump corruption control. Governments continue to be afflicted by double standards, criminalizing bribery at home but often looking the other way when bribery involves foreign officials in non-OECD countries.

Another international dimension that is closely related to corruption is the necessary monitoring of international financial flows, only a small part of which reflect real investment in the economy. Apart from speculation, these flows represent major channels for the profits of international organized crime and money laundering, which might be detected with better regulation and monitoring. There is also the crucial issue of offshore financial havens used for tax evasion, transfer pricing and unethical minimization of tax liabilities.Footnote 19 A surprising number of wealthy countries also have their own tax-free havens (domestic and in overseas territories) allowing secret ownership, front corporations, little or no reporting, and other mechanisms to facilitate accumulating and hiding wealth. Only international legislation to plug such loopholes will allow more transparency and accountability for the world’s wealth.

One other issue requiring international attention is a more ethical approach to the residual liabilities from past corruption. Too many poor and indebted countries have been drained of their resources and wealth for years by corrupt leaders.Footnote 20 When the leaders eventually fall, successor governments are still expected to pay back all the accumulated debt with interest. This is one cause of the continuing net transfer of wealth from poor to rich countries, undermining efforts to reduce poverty by 2030 as called for in the Sustainable Development Goals. On the one hand, countries that make effective efforts to stamp out corruption should be rewarded with debt forgiveness, in the context of a program of coherent economic reforms. On the other hand, much stronger international mechanisms are required to track down and recuperate the ill-gotten gains stashed abroad by corrupt leaders and their families.Footnote 21

General Strategies to Fight Corruption

The best defense against corruption is to avoid it happening to begin with, and to reduce or eliminate those situations in which corruption breeds. Much of this is best accomplished at the national level where the will exists, but much can be done within the framework of international governance to facilitate and reinforce national processes. Beyond increasing the benefits of being honest and the costs of being corrupt, one of the present authors has recently summarized some of the options.Footnote 22

For governments that can still hope to reduce corruption, what are some options for reform? Rose-Ackerman, writing in 2016, recommended a two-pronged strategy aimed at increasing the benefits of being honest and the costs of being corrupt, a sensible combination of reward and punishment as the driving force of reforms. While this is a vast subject, some complementary approaches can be proposed.

Pay civil servants well. Whether civil servants are appropriately compensated or grossly underpaid will clearly affect their motivation and incentives. If public sector wages are too low, employees may find themselves under pressure to supplement their incomes in “unofficial” ways. The IMF economists Caroline Van Rijckeghem and Beatrice Weder’s 2001 empirical work revealed that in a sample of developing countries, lower public sector wages are associated with a higher incidence of corruption – and higher wages with a lower incidence.Footnote 23

Create transparency and openness in government spending. Governments collect taxes, tap capital markets to raise money, receive foreign aid and develop mechanisms to allocate these resources to satisfy a multiplicity of needs. Some do this in ways that are relatively transparent, with a clear budget process with fiscal targets and priorities, clear authorizations and execution, public disclosure of performance, and independent reviews and audits, and try to ensure that resources will be used in the public interest. The more open and transparent the process, the less opportunity it will provide for malfeasance and abuse. The ability of citizens to scrutinize government activities and debate the merits of public policies also makes a difference. Thus, press freedoms and literacy levels will shape the context for reforms in important ways. An active civil society with a culture of participation can also be important in supporting strategies to reduce corruption.

Cut red tape. The strong correlation between the incidence of corruption and the extent of bureaucratic red tape suggests the desirability of eliminating needless regulations while safeguarding the essential regulatory functions of the state necessary for environmental and social protection, health and safety. The sorts of regulations on the books of many countries – requiring certifications and licenses for a plethora of reasons – are sometimes not only extremely burdensome but also no longer relevant. Rose-Ackerman suggests that “the most obvious approach is simply to eliminate laws and programs that breed corruption.”

Replace regressive and distorting subsidies with targeted cash transfers. Mindless subsidies, often benefiting the wealthy and vested interests, are another example of how government policy can distort incentives and create opportunities for corruption. As noted previously, according to a 2015 IMF study, consumer subsidies for energy products amount to some US$5.3 trillion a year, equivalent to about 6.5 percent of global GDP.Footnote 24 These subsidies are very regressively distributed: for gasoline, over 60 percent of benefits accrue to the richest 20 percent of households. Subsidies often lead to smuggling, to shortages and to the emergence of black markets. Leaving aside the issue of the opportunity costs (how many schools could be built with the cost of one year’s energy subsidy?), and the environmental effects associated with artificially low prices, subsidies can often put the government at the center of corruption-generating schemes. It would be much better to replace expensive, regressive subsidies with targeted cash transfers.

Deploy smart technology. Frequent, direct contact between government officials and citizens can open the way for illicit transactions. One way to address this problem is to use readily available technologies to encourage a more arm’s-length relationship between officials and civil society. The use of online platforms has been particularly successful in public procurement, perhaps one of the most fertile sources of corruption. Purchases of goods and services by the state can be sizable, amounting in most countries to somewhere between 5 and 10 percent of GDP. Because the awarding of contracts can involve bureaucratic discretion, and because most countries have long histories of graft, kickbacks and collusion in public procurement, more and more countries have opted for procedures that guarantee adequate openness and competition, a level playing field for suppliers, clear bidding procedures and the like.

Chile has used the latest technologies to create one of the world’s most transparent public procurement systems. ChileCompra, launched in 2003, is an Internet-based public system for purchasing and hiring that serves companies, public organizations and individual citizens. It is by far the largest business-to-business site in the country, involving 850 purchasing organizations. In 2012, users completed 2.1 million purchases totaling US$9.1 billion. The system has earned a worldwide reputation for excellence, transparency and efficiency.

Many other areas of reform can contribute to reducing corruption. A viable legal system with clear laws, independent judges and credible penalties, supported by a tough anticorruption agency and an ombudsperson to investigate requests for bribes, can show that a government takes the issue seriously. In aid programs, donors can do much more to ensure that the funds provided are used properly and achieve the intended results.

More generally, the types of development projects that are encouraged or supported should also be examined critically from an anticorruption perspective. For example, the tax-free zones and similar arrangements that have been established in many countries to attract foreign businesses and create employment require government subsidies and tax breaks with often ephemeral results that are not cost-effective, but local politicians love them because it is so easy to siphon off money from both government and business.

In many of these measures, the underlying philosophy is to remove the opportunity for corruption by changing incentives, closing loopholes and eliminating misconceived rules that encourage corrupt behavior. But an approach that focuses solely on changing the rules and incentives, along with imposing appropriately harsh punishment for violating the rules, is likely to be far more effective if it is also supported by efforts to buttress the moral and ethical foundations of human behavior. One of the underlying causes of corruption is the general decline or vacuum in moral standards and ethical values, and the corollary glorification of greed and excessive wealth across many societies. Efforts, whether in education, local communities or faith-based organizations, to strengthen values such as honesty, trustworthiness and aspirations that reach beyond the purely material, will always be the best defense against corruption. Such stronger ethical standards will provide a new source of strength in the struggle against corruption, complementing the progress made in recent years in improving the legal framework designed to combat bribery and corruption.

An International Anticorruption Court

To support and enhance all of these efforts to fight corruption at lower levels, binding international juridical oversight must also be established. Supranational judicial mechanisms are necessary to prosecute individuals and entities violating established norms on corruption when nations are unable to carry out such prosecutions; such a state of affairs is all too frequently the case when the political establishment and the justice system have been captured by corrupt elites. Such mechanisms could also ensure the effective adjudication of cases of corruption at the international level that escape from or fall between national jurisdictions, or that involve multinational corporations, international criminal syndicates or other transnational actors that may be difficult for any one nation to prosecute. New international mechanisms could take the form of a free-standing international court focusing on anticorruption, a special chamber of the International Criminal Court (ICC) or of an International Human Rights Tribunal, in combination with a companion technical training and implementation body.

Among the most promising proposals that has emerged to date is for a new, stand-alone International Anticorruption Court that would generally follow the model of the ICC, as currently advocated by US Senior Judge Mark Wolf and others engaged in the Integrity Initiatives International (III).Footnote 25 Judge Wolf notes that federal jurisdiction at the US national level is commonly employed to address state-level corruption, to deploy appropriate expertise, resources and independence to tackle embedded corruption effectively at the more local level. By analogy, to ensure meaningful prosecutions of corrupt national officials around the world, a higher level of oversight and enforcement is required at the international level.

The IACC model proposed by Wolf and colleagues would embrace the complementarity principle of the ICC, only stepping in with investigations and prosecutions when national courts are unwilling or unable to prosecute. Such a court could in particular target “grand corruption,” or the abuse of public office for private gain by a country’s leaders, which often translates directly into entrenched systemic national norms of corruption, and impunity for the same, as those same leaders control the law enforcement and justice apparatus.Footnote 26

A companion technical institute established at the same time as the proposed IACC could moreover have the capacity to provide innovative and unprecedented internationalized (or “hybrid”) ad hoc technical bodies for review and enforcement audits and support of prosecutions at the national level, when appropriate, in addition to general technical training. Such a body could make assessments about whether technical assistance and training would be effective in a given country (and, if so, to whom and when to deliver such training), and could consider possible hybrid prosecutions or “loaning” of highly skilled international staff in service of national prosecutions, according to specific country conditions. An international anticorruption technical institute could build on sound initiatives already begun at the international level, for example, the International Anti-Corruption Coordination Centre (IACCC), recently established and initially seated in the United Kingdom, with the goal of facilitating international cooperation and information exchange on the prosecution of grand corruption.Footnote 27 An international institute could also develop and consolidate crucial techniques and cooperative approaches to international asset location and recovery.

In order to set up an IACC (and a supporting technical institute), a transnational network could be established, akin to that which was instrumental in setting up the ICC, to advocate for this new, badly needed international institution. The global public is yet to become sufficiently aware of the comprehensive dimensions of the issue of grand corruption, including the persistent risks of cross-border infection across a range of serious issues of public concern (transnational organized crime, tax evasion, the theft of foreign development aid, sale of weapons of mass destruction, etc.). The III has set out to raise such transnational public awareness, working in particular to establish a global network of youth and young professionals throughout the world who are dedicated to fighting corruption in their home countries and at the global level.

As with proposals for the establishment of other significant international institutions, a concern commonly raised in relation to an IACC is its cost. However, corruption at the international level involves the loss of trillions of dollars every year; this staggering sum would make the funding of a new international court pale in comparison (the ICC, for example, currently costs about US$167 million annually). Moreover, convictions at the IACC would likely normally also entail the restitution of stolen funds or assets, as well as the imposition of fines, which might be used to subsidize the costs of the court.Footnote 28