Chapter 6 - Wulfstan in Truso: Old English Text, Baltic Archaeology, and World History

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 May 2022

Summary

IT IS relatively easy to identify leading examples of how (unsurprisingly) the many successive generations and changing social configurations within the population of Anglo-Saxon England were both conscious of and cared about their place within a wider known world and its history. Such evidence can be traced back in time to origin traditions that must derive from the fifth and sixth centuries AD and the connected relationships claimed and nurtured with surviving or apparently lost populations in Scandinavia and on the Continent. Bede's learning was, of course, shaped fundamentally by Christian orthodoxy and an ecclesiastical focus, but his informed awareness of geography was not limited to the biblical, with the introduction of a reference to distant visitors – presumably traders – who had witnessed the midnight sun in the Arctic into his commentary on the Book of Kings. The violent and forceful Scandinavian raiding and colonization of the Viking Age, from the end of the eighth century onwards, created a demanding new context for such reflexive thought.

Not least in light of the terminological controversy within which the origins and production of this publication have become embedded, it is pertinent to note that the adoption of the title Angulsaxonum rex for King Alfred at the very beginning of Asser's De rebus gestis Ælfredi itself prominently embodies the adoption in the court of Wessex, as a political label, of a geo-ethnic term that had become current in learned and politically leading circles on the Continent around a century before, and thus in effect represents a significant stage in the repositioning of the West Saxon leadership relative both to England and to Europe. The production of an Old English translation of Orosius’ Historiae adversus paganos in the milieu of Alfred of Wessex's court, probably in or just before the last decade of the ninth century, provided a further opportunity for that political centre to record and display the connections it had over long distances within Europe, and its knowledge of areas virtually unknown to Orosius at the end of the fourth and in the early fifth centuries.

Paulus Orosius is thought to have been born in Iberia and is known to have travelled around the Mediterranean area, especially in North Africa, and to Palestine.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

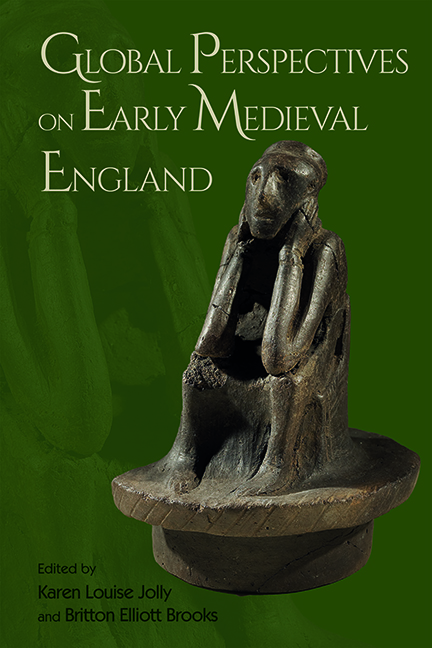

- Global Perspectives on Early Medieval England , pp. 115 - 136Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2022

- 1

- Cited by