Introduction

Mis- and mal-information pervades our everyday lives, ranging from dangerous to harmless, malicious to well intentioned. Intentional deception serves as one form of misinformation that is wide reaching, including examples that are both harmful or socially positive or acceptable. As one such example of acceptable everyday deception, when people ask how others are doing, they expect responses on some variation of “fine” or “great.” This is not only innocuous but is widely socially accepted, much akin to putting one’s “best face forward” for job interviews or on resumes, dating apps, or first dates. Misrepresentation, in these instances, may be misleading or false but are normatively expected as standard practice. People are startled when someone doesn’t respond with superficial pleasantries or positive misrepresentations. In contrast, there are many other instances in which deception is met with outrage, such as outright lies about heritage á la Rachel Dolezal, past behavior á la Hershel Walker, or professional innovation á la Elizabeth Holmes, for personal gain. In the middle is collective incredulity, as with fake product reviews or the recent phenomenon of in-person job postings labeled as remote to generate more clicks. Thus, we ask: What aspects of deception produce different perceptions? How can community governance of misinformation adjust based on social perceptions and norms?

Deception, as the various behaviors that obscure the truth, mislead, or promote falsehoods (Whaley Reference Whaley1982), is a multifaceted concept in the social sciences (Zhou Reference Zhou2005), reflecting psychological (Hyman Reference Hyman1989), sociological (Meltzer Reference Meltzer2003), communicative (Buller, Daly, and Wiemann Reference Buller, Burgoon, Daly and Wiemann1994), and legal (Klass Reference Klass2011) dimensions. So, too, is deception multifaceted in experience. We recognize that the concept of “deception” has different implications for different scholarly and everyday communities; we draw on an interdisciplinary perspective in this chapter to understand the ways in which everyday engagement with deception as a form of misinformation does and does not map onto academic conceptualization in specific contexts.

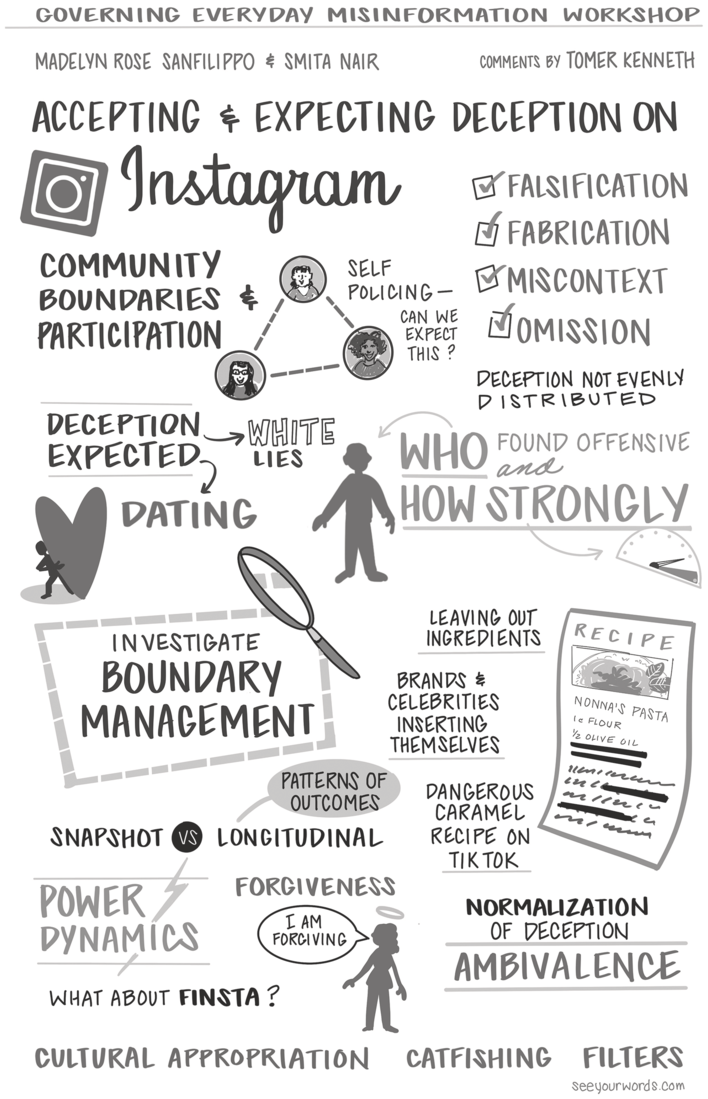

Figure 11.1 Visual themes from community governance of false, fabricated, omitted, and out of context claims on Instagram.

Background

Social Media and Deception

Social media platforms are widely trusted and integral information environments in everyday life (Rubin, Burkell, and Quan Reference Rubin, Burkell and Quan‐Haase2010), though they often lack meaningful institutionalization as associated with more traditional communication channels (Obar and Wildman Reference Obar and Wildman2015) or information resources (e.g., Mansoor Reference Mansoor2021). Because social platforms both possess a degree of decentralization (Blanke and Pybus Reference Blanke and Pybus2020) and facilitate immediate conversation (Couldry Reference Couldry2015), they lend themselves easily to everyday knowledge commons for collection and dissemination of digital resources (Sanfilippo and Strandburg Reference Sanfilippo and Strandburg2021a, Reference Sanfilippo and Strandburg2021b). As communities emerge around popular topics, members generate, use, and share information co-created within these commons. Within these sociotechnical systems, communities and individual users produce and curate valuable knowledge resources, yet they lack enforcement structures to enforce norms or rules, and, as such, typical information behavior in these environments involves generating and passively consuming information, as well as regulating mis- and disinformation on an individual scale. Community members hold a personal stake in identifying acts of deception perpetuated by misinformed or mal-intentioned actors to maintain the integrity of knowledge generation.

As knowledge commons grow, certain contributors and content creators build informal authority as “influencers,” entrusted by their communities to share products and tips that will accurately serve informational needs. These actors can be professionals within their fields or amateur content creators; as community members relate to influencers, situated strategically and visibly within networks, trust in them grows and their behaviors and preferences are normalized in the eyes of the community. Because engagement drives influencer profit, influencers are incentivized not to violate this trust. However, influencers do not always abide by social and contextual norms; often they develop strategies to achieve their own aims, contrary to social norms (Wellman, Stoldt, Tully, and Ekdale Reference Wellman, Stoldt, Tully and Ekdale2020). Among the most prevalent norm violations influencers commit are acts of deception; yet not all deception is viewed as equivalent and where there is a lack of consensus, there are opportunities to deceive without repercussion or else to salvage trust in the long term. It is important to develop better understanding of types of deception, social perceptions of these acts and associated information, and community responses to deception as misinformation.

Past scholarship of deception highlights multiple social and psychological dimensions of misrepresentation (e.g., Hyman Reference Hyman1989; Meltzer Reference Meltzer2003; Whaley Reference Whaley1982; Zhou Reference Zhou2005), emphasizing lies of omission and rational means of obfuscation (Brunton and Nissenbaum Reference Brunton and Nissenbaum2015), as well as motivations for fabrication or falsification (e.g., Kumar and Shah Reference Kumar and Shah2018). Yet, most of this research does not explore either governance of these behaviors or the characteristics of the information itself produced by deceptive behaviors. In synthesizing this research, along with literature on misinformation, information quality, and social perceptions of information, including expectations regarding contextual integrity, we propose a typology of four distinct misinformation types associated with deception: omitted information, false information, fabricated information, and information out of context. We will explore everyday misinformation, assessing the validity of these suggested constructs throughout knowledge commons associated with food, dating, and retail on Instagram, so associated for their clear subcontexts and inherent nature as co-producing community and information. The next section provides conceptual background, applying the knowledge commons frame to understand social media and associated communities on social platforms, such as Instagram.

Conceptualizing Social Media as a Knowledge Commons

Social media manifests as a polycentric arrangement of everyday knowledge commons (Sanfilippo and Strandburg Reference Sanfilippo and Strandburg2021b), wherein individuals self-arrange based on networked and algorithmically recommended points of connection to communicate, generate, and exchange content, as well as to collaboratively produce norms of interactions concurrent with the emergence of the community built upon their interactions (Sanfilippo, Frischmann, and Strandburg Reference Sanfilippo, Frischmann and Strandburg2021). This is a key attribute of knowledge commons, wherein information generation, sharing, and use are co-created with the community (Frischmann, Madison, and Strandburg Reference Frischmann, Madison and Strandburg2014), illustrating how meaningful the framing of everyday information environments as knowledge commons is in analysis.

A knowledge commons refers to shared knowledge resources, wherein sharing is institutionalized via knowledge commons governance (Frischmann, Madison, and Strandburg Reference Frischmann, Madison and Strandburg2014) as the socially collaborative production of strategies, norms, and rules that specify how particular information and information types can be shared, among whom, for what purposes, and under what conditions (Sanfilippo, Frischmann, and Strandburg Reference Sanfilippo, Frischmann and Strandburg2021). Note that strategies, norms, and rules represent a hierarchy, drawing on the institutional grammar (Sanfilippo, Frischmann, and Strandburg Reference Sanfilippo, Frischmann and Strandburg2021) in which strategies formalize functions to achieve specific aims, norms reflect consensus about the best strategies for the conditions, and rules enforce norms (Shvartzshnaider, Sanfilippo, and Apthorpe Reference Shvartzshnaider, Sanfilippo and Apthorpe2022). This perspective reflects the Governing Knowledge Commons (GKC) Framework, which has been employed to analyze action arenas around a variety of communities and information types (e.g., Frischmann, Madison, and Strandburg Reference Frischmann, Madison and Strandburg2014; Sanfilippo, Frischmann, and Strandburg Reference Sanfilippo, Frischmann and Strandburg2021).

Institutionalization of knowledge production, sharing, and use is evident throughout online communities, both those built as sites of knowledge sharing, such as Wikipedia (Morell Reference Morell, Frischmann, Madison and Strandburg2014) or Galaxy Zoo (Madison Reference Madison, Frischmann, Madison and Strandburg2014), and those built for digital mediation of communication and other social interactions, such as Facebook or Twitter (e.g., Sanfilippo and Strandburg Reference Sanfilippo and Strandburg2021a, Reference Sanfilippo and Strandburg2021b). It is not necessary for the platform or infrastructure itself to reflect commons principles to support knowledge commons. Instead, commons arrangements amongst participants build within exogenously governed sociotechnical systems; intersections between platform and community governance are often complex, but communities and individuals often innovate to arrange information flows, resources, and participation in ways that best reflect their values and objectives (Sanfilippo, Frischmann, and Strandburg Reference Sanfilippo, Frischmann and Strandburg2021). Further, the knowledge resources produced span many types of information; commons arrangements often govern personal information (Sanfilippo, Frischmann, and Strandburg Reference Sanfilippo, Frischmann and Strandburg2021), in addition to more generalizable scientific data (e.g., Geary et al Reference Geary, Reay and Bubela2019; Strandburg, Frischmann, and Madison Reference Strandburg, Frischmann and Madison2017), historical information (e.g., Murray Reference Murray, Frischmann, Madison and Strandburg2014), instructions (e.g., Meyer Reference Meyer2012; Shvartzshnaider, Sanfilippo, and Apthorpe Reference Shvartzshnaider, Sanfilippo and Apthorpe2022), or other impersonal information. It is also notable that knowledge commons may build resources that center around everything from facts to advice, opinions, and beliefs, making many of these resources subjective and context specific (Sanfilippo, Frichmann, and Strandburg Reference Sanfilippo, Frischmann and Strandburg2018). Knowledge commons arrangements often address issues of information quality and participation or exclusion as key parameters, making this framework useful to structure analysis of misinformation, given the relevance of information quality to the concept, and social interactions around misinformation.

Methods

This chapter empirically focuses on deception as a type of misinformation. To understand how online communities respond to this form of everyday misinformation, we employed qualitative and computational content analysis of public social media posts to assess how groups come to consensus about different examples of deception on Instagram. We focus on group dynamics and processes to form consensus, or deliberate by examining their language and interactions. We aim to determine what types of deception are socially acceptable and unacceptable, anticipated or expected and unanticipated, looking at three contexts: posts about food, dating, and shopping. While these three cases do not reflect the totality of everyday interactions on Instagram, they span cultures and geography and are emblematic of popular experiences with misinformation. It is of particular interest to understand how groups collectively determine what type of deception a particular post is. We also provide understanding regarding how Instagram subcommunities respond to unacceptable forms of deception. This research is significant in helping online communities develop strategies to cope with everyday misinformation, based on past success.

Criteria for inclusion are based primarily on public posts and comments on Instagram that pertain to the keywords deception, fraud, and misinformation as they intersect with the thirty most common shopping, dating, and food keywords as ranked by Best-Hashtags in 2022 (see Table 11.1). We use these keywords to identify relevant posts, and associated comments, as both hashtags and via full-text search supported by natural-language processing (NLP) via the application programming interface (API). We collected posts by a variety of user account types, from individuals with small followings to famous influences and celebrities, as well as corporate accounts, excluding only those posts made by users under the age of eighteen. These details were screened prior to collection. To appropriately anonymize the posts considered, we did not collect nor consider any user profile details during this study, including profile pictures or usernames.

Table 11.1 Contextual hashtags for sample selection

| Food | Dating | Shopping |

|---|---|---|

| #food #foodporn #foodie #instafood #foodphotography #foodstagram #yummy #foodblogger #foodlover #instagood #love #delicious #follow #like #healthyfood #homemade #dinner #foodgasm #tasty #photooftheday #foodies #restaurant #cooking #lunch #picoftheday #bhfyp #foodpics #instagram #healthy #chef | #dating #love #relationships #onlinedating #relationshipgoals #datingadvice #single #relationship #marriage #romance #datingapp #datingtips #tinder #relationshipadvice #couples #couplegoals #datinglife #datingcoach #singles #datingapps #instagood #couple #follow #datingmemes #date #lovequotes #bhfyp #singlelife #relationshipquotes #life | #shopping #fashion #style #onlineshopping #shop #love #shoppingonline #instagood #outfit #moda #instafashion #ootd #fashionblogger #dress #fashionista #sale #like #shoes #instagram #beauty #fashionstyle #follow #online #beautiful #design #onlineshop #shoponline #clothes #model #stylish |

Using a plugin to the Instagram Graph API that exclusively captured text without media, we downloaded Instagram posts, and subsequent associated comments, based on the keyword sampling design at the intersection of deception, fraud, and misinformation and shopping, dating, and food keywords in Table 11.1. We saved only the text of individual posts and comments, which we numbered in chronological order. We did not include any pseudonyms or links between comments or posts by the same user. Via the API, it is not possible to download posts without including usernames and timestamps. Thus, these details and all associated metadata were deleted immediately upon download. Upon download, posts were numbered to maintain the sequence of communication, and to assess consensus development over time. No indirect identifiers indicated whether any posts were written by the same user.

A significant concern in this research is to ensure that users cannot be identified and will not be adversely impacted in this work; we minimized data retention and dissemination, beyond aggregate qualitative analysis and communication of common words people use to describe the issues we are investigating. We do not retain or analyze usernames, profile details, photos, or metadata. We also recognize that direct quotes of public social media posts in publications could identify users and as such will not include anything more than examples of words used to describe misinformation (e.g., “deceptive” or “fraud”) which cannot be used without context to reidentify users. In addition to data minimization to exclude direct identifiers, care will be taken to avoid the use of any direct quotations in publication or presentation, which may identify users due to the public nature of the social media posts considered. As such, we used Python to strip out personally identifiable fields and converted to plain text upon download, prior to retention. A summary of the sample is provided in Table 11.2.

Table 11.2 Threads, posts collected and coded by context

| Threads | Posts collected | Posts coded | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food | 35 | 3,214 | 2,906 |

| Dating | 26 | 2,056 | 1,980 |

| Shopping | 17 | 1,824 | 1,721 |

The text was analyzed via a mixed-method content analysis approach. Qualitative analysis was structured by the Governing Knowledge Commons Framework (presented in the Introduction) and based on misinformation literature; content analysis was structured over multiple phases. First, both investigators co-coded a subsample, discussing what concepts from the literature applied and what other common themes emerge, in a grounded manner, to finalize the codebook (Table 11.3) and begin to gauge validity via inter-rater reliability. We also used this process to identify duplicate posts, which were not coded, nor were any posts not in English. Second, both investigators independently coded a second subsample and inter-rater reliability was again assessed, iterating until adequate agreement was established. Krippendorf’s alpha measures of reliability ranged from 0.81 to 0.97. Third, the remaining content was divided in two and each investigator coded independently. Themes and patterns were assessed based on this manual, qualitative coding. We also employed a computational linguistic approach to count terms in the sample that apply to specific codes of interest, in order to ascertain how users describe acts of deception and what types of deception are perceived more positively or negatively, as measures of sentiment. All protocols were approved by the UIUC IRB.

Table 11.3 Codebook for content analysis

| Concept | Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Falsification | Deliberate manipulation or misrepresentation of information | Kumar and Shah (Reference Kumar and Shah2018); Simmons and Lee (Reference Simmons and Lee2020); Whaley (Reference Whaley1982) |

| Fabrication | Deliberate invention or synthetic creation of information | Kumar and Shah (Reference Kumar and Shah2018) |

| Miscontext | Implying, insinuating, or framing something as true because it is true in another context, though it is either definitively false or uncertain in this context | Shivangi, Bregler, and Nießer (Reference Shivangi, Bregler and Nießner2021); Strathern, Crick, and Marcus (Reference Strathern, Crick and Marcus1987) |

| Omission | Exclusion of relevant data/information | Brunton and Nissenbaum (Reference Brunton and Nissenbaum2015) |

| Influencer | A social media content creator and/or brand promoter with a following typically >100k | Jin, Muqaddam, and Ryu (Reference Jin, Muqaddam and Ryu2019) |

| Cultural heritage | Communal customs, expressions, and values, passed down from generation to generation | Brown (Reference Brown2009) |

| Personal attributes | Individual qualities or features, Typically innate | Latour (Reference Latour2011) |

| Fictitious entry | Deliberately incorrect information, typically associated with humor, consumer deception, and/or honeypots | Banerjee and Chua (Reference Banerjee and Chua2017) |

| False advertising or claims | Deliberate or negligent use of dubious, untrue, or misleading information to encourage beliefs, uses, or sales | Mangus (Reference Magnus2008) |

| Misrepresentation | Intentionally or negligently false depiction of innovation, service, good, or procedure | Boutron and Ravaud (Reference Boutron and Ravaud2018) |

| Trade secret | Information that is commercially valuable, known to a limited group of people, and actively protected as a secret | Graves (Reference Graves2007) |

| Skepticism | Doubting or questioning the veracity of information, based on observations or facts | Williams (Reference Williams, Greco and Sosa2017) |

| Uncertainty | Unknown or undecided about information or judgment, often based on incomplete information | FeldmanHall and Shenhav (Reference FeldmanHall and Shenhav2019) |

| Trust | Confidence in truthfulness or accuracy | Hirschmann (Reference Hirschman1970); Sanfilippo, Frischmann, and Strandburg (Reference Sanfilippo, Frischmann and Strandburg2021) |

Comparing Governance of Everyday Deception in Three Instagram Cases

Contextual Background

Three broad subcontexts within Instagram pervasively provide examples of deception and community responses to this form of misinformation: food, dating, and shopping. In this section, we provide contextual background for each of these three cases, delineating challenges regarding the status of deception as misinformation in each, as well as examples.

Do You Mind Sharing the Recipe?

Dinner parties, potlucks, and local fairs – among other social interactions – often offer opportunities to share homemade food, from experiments without recipes to trusted, and in some cases closely guarded, family recipes. It is considered perfectly normal and appropriate to ask the cook or baker for the recipe, though some will engage a right of refusal in response. More common than flat refusal are examples in which people acquiesce to share, yet don’t share key ingredients or procedural details for a variety of reasons. For example, some steps might be hard to explain or else someone may assume tacit knowledge or generalities are understood, based on cultural backgrounds. Many share lists of ingredients without steps, a practice exacerbated by apps and platforms that gatekeep directions. Further, ingredient lists may include general references to complex mixtures, such as “Cajun spices” or garam masala. Beyond assumptions that someone else will understand, people often try to obfuscate family secrets, leaving out a key spice or method, to protect their heritage or their status as a better cook. We might describe all of these as practices of omission.

Alternatively, others may share complete information in such a way as to manage boundaries via contextually specific terminology. “Sure you can have the recipe!” Yet, they provide it in illegible photocopies of century-old handwritten Polish or Russian recipe cards, or with direction that simply say “assemble as per [name of the dish]” (e.g., a favorite family recipe handed down through my family instructs the baker to “assemble as per butterhorns”), which presumes that one can only make the recipe if they can read it, or translate, or know enough about the food to imagine the order and process of assembly. Many of these examples illustrate boundary setting, intentionally or unintentionally including and excluding based on whether others have enough domain or cultural knowledge to understand the references or make appropriate inferences from incomplete information.

Yet, foodie communities on Instagram and other social platforms, which encompass large populations with diverse interests (e.g., Calefato, La Fortuna, and Scelzi Reference Calefato, La Fortuna and Scelzi2016), experience other issues of misinformation beyond omission. In cases outside heritage recipes or traditions, issues of experimentation or substitution may contribute to deceptive instructions in intentional or unintentional ways. For example, people may genuinely not remember the order of steps taken, duration of specific steps, or ingredient details, particularly if their food philosophy is more artistic than scientific (MacGovern Reference MacGovern2021). More problematic are instances in which posts take credit for recipes or foods that are not their own; subsequent falsification and fraudulence in communication of the recipe are to be expected, when they don’t know how it was prepared or understand the nuance of culturally relevant ingredients or processes. These cases gain the most visibility around celebrity chefs and prominent influencers, rather than individuals who try to pass off takeout food as homemade and represent the more significant misinformation problem.

Food and human relationships to food reflect a complex context in which identity, culture, and social structures are strongly interrelated (Almerico Reference Almerico2014). Religion, ethnicity, and geography significantly influence our understanding of, experiences with, and relationships to food, in addition to the ways they are prepared. Food reflects a facet of everyday life that is both complex and all too seldom analyzed in a serious, scholarly manner (e.g., Aspray, Royer, and Ocepek Reference Aspray, Royer and Ocepek2013), yet it tells us what people prioritize, their traditions, their socioeconomic status, and much more about them. This is a context in which to explore everyday misinformation that importantly highlights the tensions between expertise and experience, importance of belongingness in communities and their associated knowledge commons, and distinctions between tacit and recorded knowledge. Further, it emphasizes the importance of variability and tradition in influencing information quality throughout everyday knowledge commons.

Looking for Love

Dating and courtship have historically been built on optimizing one’s assets and representing one’s “best self,” if not a “better you.” It is commonplace for people to round up their height, or lie about how tall they are, or to enhance their physical features or descriptive profile to gain attention. The use of photoshop and filters is ubiquitous on social media beyond dating profiles, but especially so in this space, in ways that build on in-real-life (IRL) enhancements, such as cosmetics, haircoloring, or surgical procedures. There are real incentives to mimic advertising strategies and produce clickbait, rather than a high-fidelity and honest profile, whether one aims for a hookup or a long-term relationship.

Some of the tactics to achieve these aims are transparently manipulative, such as posts that serve as “thirst traps,” integrating misrepresentation and sexualization on social media (Davis Reference Davis2018). They are institutionalized via clear aims and conditions, as well as normative consensus around practice in the context of dating. Popular culture and relevant communities understand their purpose and can identify them, yet they are embraced as a strategy to meet romantic and sexual needs, as well as attract attention more generally (Davis Reference Davis2018). Provocative and enhanced photos, depicting the most attractive and/or positive features are not viewed negatively or sanctioned in the context of dating. This aligns with the ways in which public relations and the concept of “spin” have influenced dating norms as commercial actors increasingly play a role in how people meet and interact (Di Domenico, Sit, Ishizaka, and Nunan Reference Di Domenico, Sit, Ishizaka and Nunan2021; Ewen Reference Ewen1996); modern dating profiles mimic retail descriptions for products, more so than the historic ways in which communities and matchmakers have depicted eligible singles across cultures. While there has always been a tendency toward representation of the individual as favorably as possible, truth is treated much more malleably in modern circumstances.

Technology plays major roles in these trends, around the world. Not only is the use of dating apps extremely common (Hobbs, Owen, and Gerber Reference Hobbs, Owen and Gerber2017; Wu and Trottier Reference Wu and Trottier2022), but social media documents and brokers many relationships as they take their course, with communities emerging around specific relationships and the context more broadly to process interactions and experiences (e.g., Hobbs, Owen, and Gerber Reference Hobbs, Owen and Gerber2017). Dating and romantic partnerships represent a significant subcommunity on Instagram, with influencers posting considerable details and many accounts dedicated to commentary on dating apps, culture, first dates observed, and humor. This also builds on online culture built around older platforms, such as Tumblr, which were so much a part of dating experiences that various countries that did not yet have dedicated dating apps in their countries used Tumblr as dating profiles (Byron, Robards, Hanckel, Vivienne, and Churchill Reference Byron, Robards, Hanckel, Vivienne and Churchill2019; Hart Reference Hart2015).

A key issue that intersects with deception in the context of dating discussion subcommunities on Instagram is that of catfishing, which engages outright lies via a false personal profile on social media to engage in fraud or deceive other users (Simmons and Lee Reference Simmons and Lee2020). This is distinct from phishing, in that the aim is not personal information or financial gain, typically, but rather social and psychological harm. Research on this issue shows a high degree of overlap in impact with misinformation in the context of dating, but motivations are identified to be quite distinct (e.g., Chen Reference Chen2016; Hancock, Toma, and Ellison Reference Hancock2007; Simmons and Lee Reference Simmons and Lee2020).

Where Can I Get One?

As digital communities form around popular themes – over any number of hobbies, such as makeup or sneaker collecting – so do “influencers” gain popularity as opinion leaders. Communities trust influencers to share tips and recommendations as normal, relatable people who seemingly have more in common with community members than brands or celebrities; emotional bond-building behaviors (directly interacting with their audience; referring to their fanbase as a “family”) drive influencer popularity and engagement. Full-time influencers earn their income through their content creation. Brand partnerships, sponsorships, and promotional deals are all typical among influencers and acceptable to community members with proper disclosure and transparency (Wellman, Stoldt, Tully, and Ekdale Reference Wellman, Stoldt, Tully and Ekdale2020).

However, community members can be sensitive to the possibility that profit – financial or social – would lead an influencer to misrepresent the truth to their audience. For instance, an influencer might endorse a product for payment, but neglect to disclose this transaction so that their endorsement (“I’m obsessed with this serum, it saved my skin!”) appears more credible or encourage fans to shop for the product through a specific URL without revealing that it’s an affiliate link.

More common are examples where deception is arguably present, but not clearly defined. Influencers may be transparent about their intent to profit yet misdirect consumers by sharing false or incomplete information to represent their brand more favorably (or, to make another influencer’s brand appear worse), “#sponsored,” yet lying about the product having officially recognized certifications. Or they may create a post to demonstrate the effects of a product while filtering or editing the image to make the product seem more effective. These examples could be described as fabrication and falsification respectively.

The bond between influencer and community can be such that, in cases unlike the first examples where deception is clearly present, community members who enjoy an influencer’s content may be more likely to contest claims of deception on their behalf. Fans may also acknowledge the deception yet try to minimize the severity (“we all make mistakes!”) or excuse the deception on external circumstances, for instance claiming that an influencer’s age or cultural background should exempt them from consequences. The relationship fans develop to an influencer can produce “an increased level of trust … akin to that felt for one’s personal friends” (Wellman, Stoldt, Tully, and Ekdale Reference Wellman, Stoldt, Tully and Ekdale2020). For this reason, fans may trust an influencer’s opinions over those of someone with relevant credentials or expertise, even when the two are incompatible.

Influencers can leverage this trust to manipulate narratives around deception. They may try to miscontextualize the consequences they face because of deception (attributing consequences to “cancel culture,” for instance, or claiming that they’re being targeted as a social minority) or question the trust of fans who believe the influencer would intentionally deceive their audience, in some cases engaging in gaslighting behaviors. Heterogeneity of personal experiences community-wide with opinion leadership, opinion seeking, and parasocial relationships fractures subcommunities and prevents consensus from forming with respect to public opinions on influencer deception or how to govern these behaviors and information.

Key Attributes

Instagram subcommunities, spanning topics from food to dating to consumer products (often fashion and cosmetic retail), have few barriers to participation. While an Instagram and/or Facebook account is required to post, content is public facing with opportunities for the average user to comment on content from celebrities, influencers, or other users, as well as to engage multiple audiences. A major issue that arises in this social environment is that of power differentials and the differences in ways that nonpowerful, nonfamous, or infamous users are governed or expected to behave, in comparison to brands or more powerful individuals.

Yet how do subcommunities arise or persist amid these everyday contexts? The answer centers on shared interests and collective negotiation of values. Not only does the topic matter, but so also do priorities. Aspiration, as a motivation, centers focus in retail communities on consumption of bags or shoes, skincare routines, or other consumer products endorsed by celebrities and influencers. It produces very different interactions than, say, those with a shared interest in socially curated and visible shopping, whose primary motivation is brand loyalty. Similarly, differences in the motivation to participate in discussion of or consumption of dating content produce very different communities; while some care primarily about advice, others care about commiseration or humor.

Intersecting with cognitive, emotional, and value-oriented motivations, are the attributes of the actors themselves. Status and reputation play a significant role in the relative visibility and influence of individuals within these communities, reflecting related research on social capital, reputation, and Instagram (e.g., Zulli Reference Zulli2018). Negotiation of social position is a complex assemblage of strategies and norms regarding representation of self (e.g., Bullingham and Vasconcelos Reference Bullingham and Vasconcelos2013) and interaction, thereby incrementally shaping how the community arranges into groups, as well as information content and personal status. In this sense, boundary management reflects informal strategies and norms, as well as being shaped via externalities associated with cultural capital and hierarchies. These behavioral and incentive attributes also contribute to the quality of information resources within the community, reflecting gossip, hearsay, and marketing that stray from any semblance of objective truth, yet are still socially valuable and often trusted.

Overall, a broad array of misinformation challenges these interactions and are ubiquitous, with communities grappling with distinctions between information quality and “messaging,” as well as social versus informational harms. Importantly, these communities, regardless of topic and motivation, perceive lies to be a form of manipulation distinct from marketing, and their discussions suggest that pervasive approaches to deal with misinformation via automated detection or user flagging are unlikely to succeed in everyday contexts.

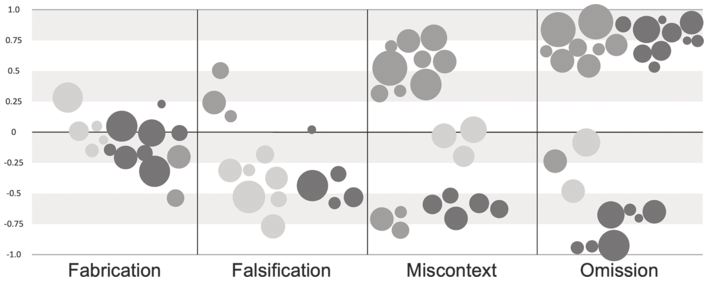

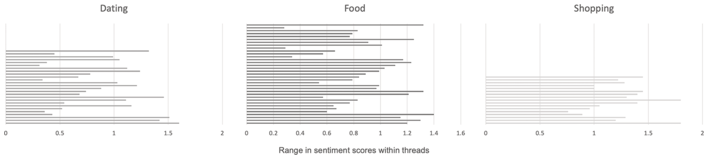

Governing Everyday Misinformation Action Arenas

Exploring deception as misinformation in food, dating, and retail subcommunities on Instagram, we find common action arenas around different types of deception, yet some divergence in community governance in response. Norms are contextually specific yet evaluated attributes and general perceptions appear to be shared. We discuss action arenas around falsification, fabrication, miscontext, and omission in subsequent subsections, drawing on qualitative coding and computational assessment of sentiment within given threads (Figure 11.2), to understand disagreement and consensus formation 8 (Figure 11.3) within action arenas.

Figure 11.2 Sentiment averages by thread, weighted by posts.

Figure 11.3 Consensus within and between threads.

Falsification

Falsification, which we define as instances of deliberate manipulation or misrepresentation of information in communication, presents nuanced governance challenges. First, it is necessary to determine whether exogenous, legal governance parameters were violated. For example, issues of false claims may merit intervention at state or federal levels in the United States, based on consumer protection, or in some cases, where contention over ownership and innovation come into play, intellectual property rights. The latter is evident amongst influencers who seek to market their own supposed innovations, when they are actually knockoffs of others’ products, processes, or devices.

Second, it is necessary for communities to determine whether the false information led to social or psychological harms to the community, as in cases of cultural appropriation and product releases or recipes on the part of major brands, celebrities, or influencers. In instances where lasting harms were identified, discussions focused on breaches of “trust” and growing “skepticism” and scrutiny about apologies and past behavior. This form of misinformation seems to pose the greatest challenge to the communities, with significant discussion about how to proceed and how actors behave or post in good faith. The average sentiment expressed across threads addressing issues of falsification was −0.51, bifurcating on issues of psychological harm, to −0.17 (no lasting harm) and −0.78 (harms).

In contrast, a form of falsification that was viewed neutrally and not perceived to be a problem, on average, were threads centered on humor driving false information in dating profiles, such as implausible career/location combinations or achievements relative to age or eloquence. Here, posters or users who falsified their information were mocked and discredited, but there was no meaningful harm to the community. This contrasts with instances of financial harms or outright catfishing.

Fabrication

Fabrication refers to the deliberate invention or creation of information as described and depicted in our typology (see Table 11.3). Examples of fabrication would include instances where brands promote information about a product that is not only untrue but entirely invented (as opposed to manipulated in cases of falsification). For example, there are many cases of brands claiming cruelty-free or other lifestyle-conscious credentials for products that have not only never received such certification but demonstrably do not meet their criteria; claiming Leaping Bunny certification yet still retailing in countries that would require their products be tested on animals, for instance, or using nonvegan ingredients. We see numerous instances of brand or influencing accounts attempting to increase the perception of information credibility within their target community in such a way that highlights a lack of respect for community values. There are many examples of brands and influencers capitalizing on the collaborative nature of digital information environments, for instance such as by posing as community members to leave fake reviews for products or otherwise endorsing a brand under explicitly false premises.

Often in threads discussing acts of deception in sales, we see discussion of community retribution as well that may indicate greater faith in communal policing than exogenous administration; for instance, commenters may question the lack of involvement from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) or confer with others in the thread over whether an FTC-enforced penalty is appropriate for the severity of the deception. Many responses indicate that individuals have reported these issues to the Better Business Bureau (BBB) or encourage others to do so. Predictably, commenters are less likely to endorse a penalty if they find the offending account’s actions acceptable, but acceptability on an individual scale isn’t always dependent on whether deception is believed to be present. For instance, a commenter may perceive but disregard deception if they plan to continue purchasing from the offending brand.

Threads for exchanging opinions on deception indicate that commenters may perceive deceptive marketing of credible information as a distinct (and not necessarily equally unforgivable) circumstance separate from deceptive information. Commenters may be more inclined to accept the former if they perceive the behaviors separately, with arguments that deceptive marketing behavior is “common practice” within the digital sales industry and unrelated to the quality of the product. This is supported by an average sentiment measure of 0.35 across four threads that illustrate this pattern is generally viewed near neutrally across individuals. More specifically, given the range of sentiment, as distributed throughout these four threads (see Figures 11.2 and 11.3), consensus is reached around neutrality for three of four, through the course of the thread; while the latter is more mixed in attitudes, perceptions lack significant amplitude, illustrating minor disagreement.

Omission

Another key form of deceptive misinformation is omission, which we define as exclusion of relevant data or information. Omission is diverse across all three contexts on Instagram, ranging from the omission of sensitive characteristics in volatile or especially public discussions, to protect privacy and promote safety, as well as the omission of key facts or information pertinent to socially relevant knowledge, for purposes of personal gain.

In many examples, when individuals leave out sensitive characteristics, this is perceived to be perfectly rational and advisable behavior. We see social consensus around the appropriateness of leaving out race, gender, sexual orientation, or other characteristics that may denote an individual as vulnerable or stigmatized in certain situations. Such examples are most prominent in threads discussing dating and other romantic norms. Keywords associated with safety, reasonableness, rationality, and justification describe these perceptions, for which the average sentiment measurements of these posts is 0.92. There is notably also a high degree of certainty expressed in these posts, ranging from 0.71 to 0.94. Similar behaviors and favorable interpretation of the omissions are also evident in threads stemming from food posts in which cooks leave out details that could be relevant to the cultural authenticity of shared recipes or food images, but reflect contentious geopolitics, such as not sharing details relative to ancestry in Palestine or Israel in posts related to Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cuisine. Sentiment in responding posts measured 0.87, on average.

These examples are sharp contrasts with the few threads sampled that demonstrated omission to obscure nonbelongingness into a given community or cultural identity; in those instances, it was perceived to be deception via implicit communication as opposed to omission for the purpose of safety. For example, Caucasian American or European influencers implying BIPOC ancestry via implicit communication, without specifying their race or ethnicity, was viewed negatively; responses to these posts measured −0.69. Few responses gave the original poster the benefit of the doubt in these cases, with the only exceptions tying into social capital dynamics, wherein powerful and esteemed individuals might be forgiven.

Another recurring issue around omission pertains to examples in which key details or facts have been left out of processes. For example, there are many recipes shared on Instagram without complete instructions or with relative ambiguity regarding culturally specific ingredients such as garam masala, Chinese 5 spice, or a culturally nonspecific phrasing of season to taste. This is generally not viewed negatively, except for those users who post as detractors and display their xenophobia or particular biases or prejudices against relevant communities. This represents a problem for public opinion that is not inherently about the misinformation problem. In these instances of discrimination, the average sentiment expressed in comments responding to these posts are the most extremely negative included in this study, measuring −.97. Here, the intersection of misinformation and racial discrimination presents an action arena that associated communities take more seriously than any other instances of misinformation examined in this research. Dialogue emerges around how to appropriately address these issues, removing misinformation, while not allowing the problematic poster to simply move on unscathed. The social consensus that we should not simply let this go contrasts with other examples such as controversies around product endorsement that miss information associated with celebrities, as in the Pharrell case, where fans allow the celebrity to move on without consequence.

Out of Context

Deception via information out of context is evidenced by implying, insinuating, or framing something as true because it is true in another context, though it is either definitively false or uncertain in this context, as described and depicted in our typology (see Table 11.3).

One distinct set of examples in which deception via miscontextual information is evident includes those instances when public figures, publications, or other influential accounts communicate culturally, ethnically, or religiously relevant information that is true for those within the community but does not reflect the heritage or community membership of the poster. For example, there are various instances in which the lack of nuance or respect shown for recipes or food associated with religious holidays highlights the nonbelongingness of the poster. We see examples in which ethnically ambiguous influencers or celebrity chefs share what are supposedly family recipes associated with cultural heritage or religious feasts, yet are appropriated from cultural traditions or communities to which they do not belong. Examples range from framing Juneteenth or Kwanzaa celebrations and family traditions by white influencers or publicly Christian chefs claiming family Passover traditions. These examples are distinctly viewed as inappropriate forms of deception, by and large, with an average sentiment of responding posts at −0.63, which indicates the conversation following the initial post is negative in tone.

Similarly, we see various threads discussing the appropriateness or inappropriateness of individuals who create profiles for themselves on culturally specific dating websites or apps, wherein they represent themselves accurately but for their membership in the relevant community group. Sometimes these practices are perceived to be acceptable, such as when individuals have not misrepresented themselves per se but are found to be out of context based on algorithmic inferences about missing attributes, which may be justified as with gender identity or sexual orientation. These threads measure average sentiment of 0.54, indicating an overall slightly positive tone. There are times these practices are perceived to be unacceptable, as evidenced by an average sentiment measure of −0.71, such as when individuals intentionally and knowingly impersonate other cultural identities, as with individuals creating J date profiles when they are not, in fact, Jewish.

We also see forms of deception through information out of context with respect to dating profiles and behaviors that are viewed neutrally to positively, with threads scoring from 0.35 to 0.76 in average sentiment, wherein posters comment on sharing accomplishments, education, or employment details in ways that are deceptive based on context, such as individuals labeling themselves as alumni of prestigious universities or programs, though they did not graduate or perhaps only attended a semester-long program, rather than a full degree program. Here, many posters argue these practices are “par for the course” or to be “expected” in the modern dating culture.

Patterns/Outcomes

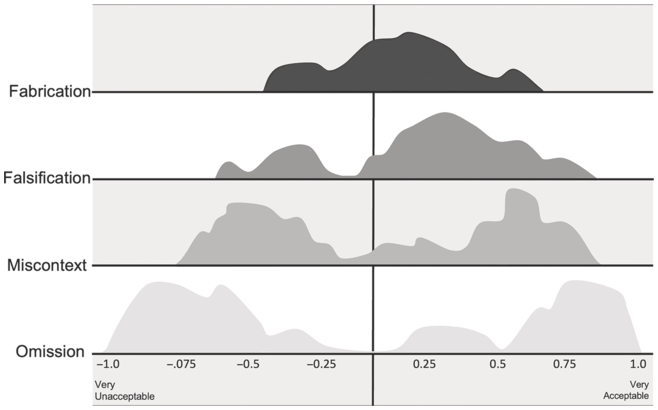

A spectrum of acceptability, from very acceptable to very unacceptable emerges from these action arenas, overall, as depicted in Figure 11.4.

Figure 11.4 Sentiment distributions by action arena, weighted by number of posts.

We see deception via miscontext and omission as viewed benignly, along with most instances of fabrication. The exceptions here are a few comparatively rare instances in which harms are more lasting, which aligns with the overwhelmingly negative responses to cases of falsification. While exogenous governance can be useful to deal with instances in which consumer deception takes place, communities must also reach consensus to deal with the local implications within their communities, more so for the regulation of their community boundaries and future participation norms than for information quality. In this sense, while examples of medical and political misinformation spread within existing social networks, the examples of everyday misinformation studied herein are contextually dependent on social capital, norms, and values. Institutionalization regarding appropriate, or at the very least acceptable, manipulation of content really needs to address power dynamics, platform visibility, and enforcement mechanisms, more so than content standards themselves.

Another key pattern is that people are willing to accept deception if they agree with it or if they see individual benefits to overlooking deception, as with various celebrities they prefer not to “cancel.” Fans might either deny wrongdoing on an influencer’s behalf, or attribute wrongdoing to cultural differences or other factors that could excuse deception. For example: Fans of influencers claim an influencer’s cultural background excuses their deception, frame an influencer’s purposeful deception is a mistake or learning opportunity, or negate influencers’ deceptions by pointing out that critics have likely also been dishonest at some point themselves. Under an influencer’s apology post, comments are largely forgiving, echoing sentiment that making mistakes is part of human nature and encouraging influencer to learn and grow. However, people appear to love people more than they love brands. Responses to brand deception are on average much less forgiving; at best, commenters may remark on the triviality of the deception.

That commenters who defend influencers are much more favorable and fervent reflects the sort of cult of personality that emerges around the personas portrayed. Often, the behaviors of famous people are excused even though others find the behavior unacceptable for the average person. Commenters also mention trust at a far greater rate when commenting on influencer deception versus brand deception, regardless of in a positive or negative context (“I still trust them” versus “they betrayed our trust”), indicates higher emotional stakes in influencer deception versus brand or celebrity.

Deception as misinformation experienced in everyday knowledge commons is most problematic in terms of issues of trust, fragmenting communities or damaging relationships between influencers and followers, rather than the information itself posing the harm. In this sense, the most serious objections expressed are about social and psychological harms, rather than information quality.

Conclusions

Despite negative connotations of deception as associated with manipulation, deception with respect to misinformation generates diverse social perceptions. On the one hand, various forms of deception that are associated with issues of identity and values of safety or privacy – including issues of gender identity, sexuality, religious or philosophical beliefs, and ethnicity or cultural identity – are perceived to be normatively and logically justifiable. This is especially true with deception via omission. On the other hand, forms of deception that aim to enrich the original poster at the expense of the community or that demonstrate bias or cultural illiteracy are largely viewed negatively. Social acceptance along the lines of normative justifications and social harms help to explain this spectrum of perceptions, as described in greater detail in Section “Patterns/Outcomes.” Social expectations align with acceptance of deception that minimizes social harms, in that we expect people not to make others uncomfortable in polite conversation, thus deception to frames information or communication in a normative format is not only desirable, but also anticipated as the default for interaction.

A key takeaway, thus, is that misinformation in everyday knowledge commons is as much a quality of valued knowledge resources to these communities as privacy is to contact information or location data as knowledge resources. The series of governance challenges, or action arenas, that arise around everyday misinformation reflect intersections with other social challenges. This certainly raises the question: Is misinformation an externality of social issues, such as mistrust in science or political contention, in other contexts, as well?

We also identify specific implications of this work for community and platform governance regarding misinformation as a dimension of information quality in everyday knowledge commons. First, it is important that mechanisms by which community members can exercise voice and consensus can build around evaluation of knowledge quality are essential to the construction of healthy, sustainable everyday knowledge commons (e.g., Hirschmann Reference Hirschman1970; Sanfilippo, Frischmann, and Strandburg Reference Sanfilippo, Frischmann and Strandburg2021). Second, it is important to recognize the nuance of social dimensions in evaluating deception as a form of misinformation. It is not possible to address many of these instances of misinformation via automated or other primarily technological means. Instead, it is critical that the approach to deal with these forms of misinformation be sociotechnical in nature and oriented at the level of communities. Infrastructure that communities can use to appropriately address issues of misinformation they deem to be unacceptable is a much more worthwhile investment at the platform level. Third, both prior recommendations also illustrate the intersection of platform level design and community level actions; we must recognize that there is no panacea to address misinformation and communities must have the flexibility to address problematic misinformation in context.

Recognizing the parallels between this key takeaway and Ostromian institutional analysis, there are meaningful implications from this work for the GKC framework. It is absolutely necessary to recognize that attributes of information, including metadata, context, and perception, are equally as important to governance of misinformation in everyday knowledge commons as the category of information itself. A more granular analysis of these attributes can help us to understand why patterns diverge around deception, among other types of misinformation, as well as how to compare contextual action arenas around similar information types.