4.1 Allocating Gifts

The humanitarian sector facilitates the flow of money, goods, or services to people in dire need and tries ‘to be as fair as possible in an unfair world’.Footnote 1 In neoclassical economics – the doctrine that has conditioned humanitarianism for more than a century – the key concern is the allocation of resources with maximum efficiency, based on information, including prices, transmitted by markets. This tends to reinforce the prevailing pattern of distribution, which is seen as an ‘equilibrium’ in accordance with the common good. Such a pattern does not address inequalities and needs, and is indifferent to an individual’s claim to a right of subsistence.Footnote 2 Donor decisions, on the other hand, are driven less by notions of efficiency and more by an emotional response to aid appeals; political, religious, or communal affiliations; or what they consider to be appropriate and fair. Humanitarian organisations are bound to consider such preferences in any given crisis, while at the same time recognising what impact allocation decisions have as moral statement and what they might mean for future donor behaviour.Footnote 3

The sphere of charity is thus a subsidiary market that lacks a price mechanism which would facilitate basic transactions, and that is only loosely linked to the final destination of relief goods. The market for donations, which calibrates sponsor motivation and information provided by aid organisations and the media, depends generally on discretionary sums. This volatile market for contributions is not supported by a comparably efficient mechanism informing aid organisations about which needs to address. On the contrary, a prevailing disaster tends to prevent recipients from being able to offer money in exchange for provisions (and thus from sending the usual signals that a market needs to function). The relief effort lacks the clearing mechanism of regular markets and depends primarily on reports from activists and the press.

Donors generally find it difficult to assess and compare the effectiveness and efficiency of voluntary organisations in allocating relief, although low overheads, presence on the ground, and the ability to elicit further funding are seen as important ‘selling points’. At the same time, while working on emergencies, aid agencies confront uncertainties far exceeding those of ordinary markets. Organisations may have to ‘second-guess the needs of the beneficiaries’,Footnote 4 rely primarily on trust, and establish their own targeting priorities. This includes attempts to internalise human suffering into economic calculations as a ‘deprivation cost’; utilising planning and controlling instruments (such as the ‘Public Equitable Allocation of Resources Log’) and individual needs assessment tools (such as the mid-upper arm circumference tape); and the creation of other relief metrics and algorithms.Footnote 5

Efficient versus Engaging Allocation

The basic problem of humanitarianism resembles that of economics-at-large, namely, the differential of scarce resources and the wants that exceed them. However, while the economy proper is construed as settling down to a relative equilibrium, humanitarianism suffers from an overall mismatch between inelastic, morally charged subsistence requirements, and the means to satisfy them. As a result, many needs remain unaddressed, resulting in suffering and death. Under such circumstances, any effort by donors or humanitarian organisations carries with it an ‘awesome responsibility’ in view of the ‘moral opportunity costs’ that arise when some people are privileged as beneficiaries over others with similar needs.Footnote 6

Although choices are inevitable, the only aspect that surfaces is usually the positive allocation decision. A large body of research suggests that the actual severity of a humanitarian cause is a secondary criterion. More significant are media attention, the perceived merits of potential recipients, and even more so the self-interest and herd behaviour of donors. A project idea that appears appropriate and manageable for a particular organisation tends to outweigh the concern of that organisation over beneficiaries.Footnote 7 Practices of screening affected people and identifying potential recipients vary widely, although vulnerable children and mothers are frequently among those chosen. At the same time, aid agencies throughout history have sometimes misinterpreted the needs of recipients and delivered inappropriate goods. Similarly, donors have burdened relief transactions with complicated demands and unsolicited items.

Against such tendencies, a recently developed ‘Greatest Good Donation Calculator’ seeks to educate contributors about the advantages of giving cash over gifts-in-kind.Footnote 8 In addition, an ‘effective altruism’ movement, based on a consequentialist utilitarian theory of ethics, has called for recasting humanitarian aid with a focus on (1) how many people benefit from an initiative and to what extent; (2) best practices; (3) everyday calamities, underserved places, and most needy causes, rather than simply major disasters; (4) genuine contributions and avoidance of bandwagon effects; and (5) weighing risks and potential gains.Footnote 9 However, these strategies are not new and are typical of the organised humanitarianism of the early and mid-twentieth century.

A study of how Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) justifies the opening, closing, or restructuring of projects illustrates different contemporary approaches. Three types of legitimation were found to prevail. The first was based on statistical comparison and resembles the mass-oriented perspective taken by organised humanitarianism and the effective altruism movement. However, it was found to be of limited applicability. The other two are reference to one’s organisational mission and identity, and solidarity with and advocacy on behalf of destitute communities. Both are self-centred or relational, founded on a deontological (i.e., rule-based) understanding of ethics. They can be traced back to earlier humanitarian campaigns, but are particularly reflective of present-day expressive humanitarianism. As both identity and solidarity entail bias towards a status quo orientation of humanitarian commitments, a balanced approach has been advocated in which the inclination of fieldworkers to ‘go native’ is regularly challenged by the distanced attitude of headquarters of aid organisations.Footnote 10

The logic of fieldwork and disaster response correlates with the ‘rule of rescue’, namely, focusing on identifiable individuals rather than maximising abstract aid. The rule stresses the agility and effectiveness of concrete humanitarian efforts over their cost and efficiency in the long view. From a situational perspective, the question of alternative resource allocation may appear as a ‘lack of moral concern’. However, humanitarian organisations generally need to find a balance between deontological and consequential approaches when planning relief efforts.Footnote 11 Famines hold an intermediate position on the urgency continuum. They are usually attributed in part to natural causes, but tend to have a more complex character than such sudden-onset disasters as earthquakes, storms, or floods.

Humanitarian Logistics, Nutrition, and Their Pull-Effect

Prompted by failures after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, humanitarian logistics has become a field of increased research and social engineering. Issues discussed include inter-agency trust and product-centred cluster formation; lessons that may be learned from commercial logistics and humanitarian–private partnerships; the integration of relief and development programmes; examples of good practice; the seamless transition between in-kind and cash modalities of relief (turning beneficiaries into customers); return of investment for emergency preparedness (i.e., conserving money through a well-planned relief infrastructure); and providing services in a businesslike manner.Footnote 12 This agenda correlates with the displacement of social nutrition approaches by apolitical and medicalising ones over the past two decades. There has been a shift from providing ordinary foodstuffs to delivering therapeutical nutrition (such as high-energy biscuits) for malnourished people. Feeding programmes are no longer based on patronage, but on anthropometric indicators.Footnote 13

Logistics research frequently points out that 60–80 per cent of the budget of aid organisations is consumed by logistics.Footnote 14 However, these figures include not only delivery costs, but also the purchase of relief goods. Recent studies have found that among logistics expenses, procurement costs ranged from 84 per cent for the Red Cross to 28 per cent for Action Contre la Faim, reflecting different organisational structures, mission profiles, and procurement sources.Footnote 15

Apart from the asymmetry of its gift economy, famine relief presents a unique logistical challenge as it tends to operate in peripheral areas where there is inadequate infrastructure and a lack of time and opportunity for systematic capacity-building. Therefore, it is frequently based on a combination of commercial models with rapid, less cost-sensitive military contingency management and needs-based approaches. Critical factors for an effective response are structural flexibility, coordination, and the management of disparate information, particularly the utilisation of local knowledge and resources.Footnote 16

Material supplies are generally provided to recipients at delivery nodes (including distribution points, soup kitchens, feeding centres, etc.). Arranging for pick-up, beyond what supply chain management regards as the ‘last mile’, is left to the ultimate beneficiary, who needs to retrieve provisions at the aid organisation’s chosen distribution site. The confusion of delivery stations with ‘demand points’ is indicative of the prevailing moral economy and of the technocratic leanness of certain logistics frames.Footnote 17 Market-based solutions, cash transfer programmes, or the availability of individual delivery services influence distribution, but still presuppose a functioning infrastructure and efforts by recipients, sometimes considerable, to obtain the goods needed. Little discussed is how the improvement of food security, something evident as one moves up the aid chain, exerts a pull-effect on recipients. Thus, the last mile for aid agencies is frequently the second mile to the source of supplies for those in need, and can take them across their homeland, to neighbouring countries, and across the sea (directly and as a domino effect).

The moral dilemmas thereby created are a trade-off between logistic costs and the proportionality of relief, or efficiency and fairness. There is a bias towards depreciating material standards with distance from the centre, and the ‘creative’ disruption caused by the pull of relief and the imagination of a better life may go along with both voluntary and forced migration. Aid organisations also need to consider the impact of their allocations on donor behaviour, such as the request for speedy disbursal or demands for privileging certain groups of recipients. The history of ‘humanitarian practices as practices’ in the field is one that includes the complicity of humanitarian efforts with acts of ‘systemic violence’.Footnote 18

4.2 Fostering Local Efforts: Ireland

The partial Irish potato failure of autumn 1845 marked the beginning of the Great Famine. Although the catastrophe had been alleviated by local charity (supplemented by a few overseas donations), public works programmes, and the government purchase and sale of Indian corn, there was worse to come. In the following season, the new Whig government was unwilling to interfere with the almost complete failure of the potato crop. Not only did officials refuse to interfere with the food market, but they also tightened the rules governing public works. While the public works scheme expanded rapidly in the winter of 1846/7, it proved to be ineffective, demoralising, and tremendously expensive. Offsetting those costs through local taxation remained a treasury pipe dream.

Voluntary soup relief preceded the soup provision programme that Westminster later adopted. It was a stop-gap during a period of policy adjustment in the spring of 1847, when neither food nor wages were forthcoming from the government. While different forms of charity – partly collaborative and partly antagonistic – coexisted, the largest of such organisations, the British Relief Association (BRA), was in fact a proxy of the government responsible for stimulating local Irish relief committees by assisting them in the acquisition of foodstuffs. Quaker and independent committees also attempted to sell tickets for meals to local benefactors, or to the hungry themselves, but they saw the need for gratuitous relief as well. Money that was collected and sent to Ireland underpinned this economy of provision. However, the Catholic Church and private donors also forwarded cash to parish priests and others in the stricken area, and sometimes directly to the starving poor. Concrete relief allocation caused shifts in the population and, in turn, shaped demands for aid. The search for food, other relief, and ultimately improved living conditions either in England or North America also increased the pressure on donors to provide shelter for displaced people, even if it were under their own roofs.

Aid for Sale: The BRA

In February 1847, James Crawford Caffin, captain of one of the first relief ships the BRA sent to Ireland, presented the admiralty with graphic accounts of distress on the country’s south-western headland. The captain concluded by noting that autopsies of people who had starved to death revealed that ‘the inner membrane of the stomach turns into a white mucus, as if nature had supported herself upon herself, until exhaustion of all the humours of the system has taken place’. He only parenthetically mentioned his own cargo of foodstuffs and did not say that he was engaged by a humanitarian organisation that was prepared to do work on the ground. Instead, he simply requested gratuitous relief for the distressed people.Footnote 19

When a London newspaper published the captain’s letter, the BRA reacted immediately. In a Letter to the Editor, its chairman pointed out in defense of the BRA that the captain’s ship had been laden with goods from a committee advised by the BRA. Additional cargoes, he asserted, had been placed under the management of their agent on site. He explained it in this way in order to do ‘justice to the efforts of the British Association, and for the satisfaction of the humane feelings of the public’.Footnote 20 On a later occasion, when the captain delivered a different cargo, a newspaper published another letter of his in which he thanked the head of the tiny London-based United Relief Association (URA) for supplying him with £10 in cash, ‘for really the demands upon my own purse were so many and great, that I should soon be a beggar, or else have to steel my heart against the misery and woe around me’. Once again, Caffin urged the provision of gratuitous relief, a practice to which the URA, but not the BRA, was committed.Footnote 21

The BRA was assigned the relief of remote parishes in western and southern Ireland in collaboration with local committees. It utilised existing administrative and logistic structures, and generally duplicated government standards. Treasury instructions ‘to consider the operations of the [BRA] Committee as identical … with the Government operations’ reveal its semi-official character.Footnote 22 The BRA’s mission was not saving lives as such, but correcting market failures and developing commercial structures in remote areas in ways that would not ‘come into competition with our merchants and upset all their calculations’.Footnote 23 The means to achieve this were two-fold: supply side intervention in shipping foodstuffs to Ireland and their distribution through a network of depots; and stabilisation of the demand on the market for food by facilitating local charitable action (Figure 4.1). In fact, what the BRA did was sell provisions at cost to local relief committees which, in turn, allocated these for gratis distribution to families in distress who lacked a breadwinner.Footnote 24

In this way, British aid utilised Irish charities to bridge the gap that remained between the demand of people who could afford to pay for food, and those whose vital need for sustenance still existed, regardless of market ‘equilibrium’. Such an arrangement was intended to multiply the resources available to relieve distress, thereby maximising their impact as follows: revenues from the sale of food would enable the purchase of further relief goods, while at the same time local charities, who knew the deserving poor, would handle the distribution of relief, thus putting donations to work in the most efficient way. These goals were all achieved. The proceeds from the sale of food (and, on a much smaller scale, seed) by the BRA in Ireland were spent for additional relief, while reports of abuse were rare.Footnote 25

However, this approach was not without difficulties. When the BRA sent their first fieldworker, Henry Cooke Harston, then on leave from the Royal Navy, to the area west of Cork in January 1847, their instructions cautioned that ‘in the present excited state of men’s minds exaggeration and misrepresentation must prevail to an unusual extent’.Footnote 26 Thus, even after the harrowing report of the two deputies from Skibbereen that led to the establishment of the BRA, the organisation still gravely underestimated the famine.Footnote 27 While Harston’s communication in the following months concerned technical matters regarding the campaign, he noted in dismay that half the population in his area was beyond recovery and doomed to die.Footnote 28 Another fieldworker informed headquarters that the distress had ‘reached such degree of lamentable extremes, that it becomes above the power of exaggeration and misrepresentation’, adding that ‘you may now believe anything which you hear and read, because what I actually see surpasses what I ever read of past and present calamities’.Footnote 29 Although its agents provided the BRA committee with a more realistic understanding of the famine, there was no revision of the approach. Instead, the BRA gave fieldworkers the following striking instructions:

The funds … being thus insufficient to secure the result which would be wished, it is most desirable to economize them as far as practicable. Urgent cases, of necessity must, it is true, be provided for at all hazards; but it must be always remembered that caution to economy … will be the best security against the general spread of famine throughout the country. The object of your mission being the early relief of distress[.]Footnote 30

BRA personnel on the ground were told that finite resources were not to be expended on those whose prospects of survival were uncertain. The instructions pointed out that while the ‘essential duty of an agent’ was to sell provisions to local committees at cost, the BRA also authorised them to make gifts of aid up to the value of one-tenth of local subscriptions. Should any ‘extraordinary’ additional grant be advisable, the agent was to justify his recommendation in a letter to London.Footnote 31 These new guidelines were liberal compared to those given to the first agent, which limited him to selling provisions to relief committees ‘for cash only’.Footnote 32

Despite the sales philosophy, grants became the dominant form of relief distributed by the BRA. While information on unsettled purchases is lacking, it seems such cases were retrospectively treated as grants. The UK government provided infrastructural support, including reimbursement of freight charges. Since other overhead costs were low, the £391,700 in donations that the BRA received for Ireland largely corresponded to the prime cost of aid. Provisions for more than two-thirds of this amount were distributed free of charge. Food and seed sold in Ireland yielded approximately £125,000. Moreover, since Irish relief committees defrayed only two-fifths of the costs of foodstuffs sold, the UK government paid for the rest, showing the discrepancy between on-site sales projections and receipts. Due to the dire conditions in Ireland, the BRA became more generous and instituted alternative procedures. However, despite the failure of the plan to sell provisions to the affected communities, the income generated allowed the BRA to mount the final phase of its relief effort. Beginning in autumn 1847, the organisation spent more than £123,000 to feed and clothe school children in the most distressed areas of Ireland.Footnote 33

Initially, the BRA was determined never to distribute money to ‘parties relieved’, assuming that cash could easily be abused and that it would have an inflationary tendency, whereas supplying food would have the opposite effect.Footnote 34 The BRA’s earliest instructions reformulated this as pertaining to ‘applicants for relief’. Agents were ordered to find places where cash grants might be appropriate and identify trustworthy people for the administration of the funds.Footnote 35 Subsequently, £7,250 in cash was transferred to certain national Irish relief organisations, along with another £10,000 in conjunction with a request by the government for allocation of the Queen’s Letter Fund to the General Central Relief Committee for All Ireland (GCRC). Small grants of money to local relief committees and their representatives amounted to £3,692.Footnote 36

A striking example of how important voluntary contributions were to official agencies, and the cynicism of the prevailing policy, may be seen in a request Treasury Secretary Trevelyan made to the BRA. Recounting the mental and physical suffering of officers involved in relief work (and anticipating Captain Caffin’s second letter), he suggested the following:

It would be a great act of charity, not only to the people themselves, but to our officers, who often have to witness the dreadful distress of the people without being able to afford them any immediate relief, if you would place at the absolute disposal of such of our Inspecting Officers as you have entire confidence in, moderate sums of money (say £100 at a time), to be employed by them entirely at their discretion.Footnote 37

Despite the BRA’s close interaction with Trevelyan and its customary compliance with government directives, the request was initially dismissed. When it was brought up again after a few weeks, the BRA granted £50 worth of provisions to each government inspector and the same to its own agents.Footnote 38

Earmarking for particular localities proved complicated for the BRA, but it had the potential of attracting more donors. The organisation’s distribution key, according to which one-sixth of the collection went to Scotland and five-sixths to Ireland, was not to everyone’s satisfaction: some asked for a different ratio or preferred to give money to only one cause. Keeping track of such matters in accounting and reporting to the public would have been an intricate task. Instead, the BRA acknowledged individual contributors and the designated recipients of their gifts in advertised lists of donors, but they made sure that Scotland’s one-sixth share included any amounts specifically contributed for that country.Footnote 39

Narrower earmarking was not very common. While the BRA stated that contributions for certain districts would strictly be observed,Footnote 40 the organisation did not live up to its own standard. This is illustrated by an anonymous Irish landlord’s gift of £1,000 to the poor of Skibbereen.Footnote 41 When the Skibbereen Relief Committee requested that the sum be dispersed, they were told that the BRA had shipped provisions to neighbouring ports, the distribution of which was delayed, but underway. In addition, they were informed that the BRA had ‘no power to transmit to you the sums of money you ask for’.Footnote 42

Richard B. Townsend, one of the former Skibbereen deputies to London, made the affair public and demanded to know by what right the BRA had withheld the money, diverting it for general purposes while continuing to sell provisions in Skibbereen. He listed the ways in which this action was disastrous: relief was delayed; the cash sum would have made the Skibbereen Relief Committee eligible for a government grant doubling the amount; the public announcement of the gift most likely caused donations to be sent to other places, which, at the same time, might be recipients ‘of that which ought to be ours!’ – all with potentially fatal consequences for Skibbereen.Footnote 43 In fact, mortality in the Skibbereen workhouse was the highest in Ireland at the time, reflecting the destitution of the surrounding area.Footnote 44 In a subsequent letter, Townsend appealed to his correspondent’s ‘own sense of Justice’, while asserting that the Skibbereeners’ belief in their entitlement was unimpaired by the distress that they endured. While Townsend realised that the BRA had the advantage, he claimed the moral high ground for not letting philanthropic wrong-doing pass without reproach. ‘We have right’, he insisted, and requested the £1,000 for Skibbereen.Footnote 45

The letter caused the BRA to ascertain the intention of the donor and explain to him the chosen mode of allocation. However, while this was happening, the committee ordered the allotment of £1,000 in weekly instalments of £100 worth of provisions, half of which was to be given to the Skibbereen Relief Committee, and the other half to neighbouring parishes that were selected because of their historical attachment to Skibbereen.Footnote 46 The Skibbereeners acquiesced and passed a vote of gratitude, although one of their members criticised the arrangement for ‘justice but by halves’.Footnote 47 The identity of the donor was not revealed at the time, despite Townsend’s awareness that it was the young Lord Dufferin, author of a pamphlet about the famine in Skibbereen.Footnote 48 However, through a British bank, the BRA consulted Frederick Pigou, a confidant of Dufferin. On being informed that the chairman of the Skibbereen union had approved the BRA model, Pigou declared his perfect satisfaction.Footnote 49

Soup Kitchens

During the Irish Famine, a well-known charity body determined it would strive ‘to exercise great caution in furnishing gratuitous supplies of food; to endeavour to call forth and assist local exertions … and to seek to economise the consumption of bread-stuffs, by promoting the establishment of soup shops.’Footnote 50 What sounds like a government declaration was in fact a mission statement by the Society of Friends. Soup kitchens set up in times of distress were a Quaker hallmark deployed at the end of 1846 along with other local groups.Footnote 51 A Quaker kitchen opened on 7 November of that year in the city of Clonmel, and on the same day an independent soup kitchen began operating in Skibbereen.Footnote 52 These may have been the first large establishments of their kind. Earlier examples include a soup kitchen in Kilcoe parish, not far from the Skibbereen neighbourhood, which was already operating in September 1846.Footnote 53

In the official relief work documentation of the period, the word ‘soup’ first appears in the description of a meeting the home secretary and Trevelyan had with the two deputies from Skibbereen.Footnote 54 At the time, a request for permission to open soup shops with local taxpayer’s money by their poor-law union was declined.Footnote 55 Instead, by the end of December 1846, a government agent had incorporated the local soup committee into a public–private partnership that set a precedent for Ireland. The arrangement doubled local subscriptions, included officials, and used the services of a policeman to fortify a humanitarian space to ensure that ‘the articles purchased for the soup are actually put into it, that it is distributed at twelve o’clock precisely’.Footnote 56

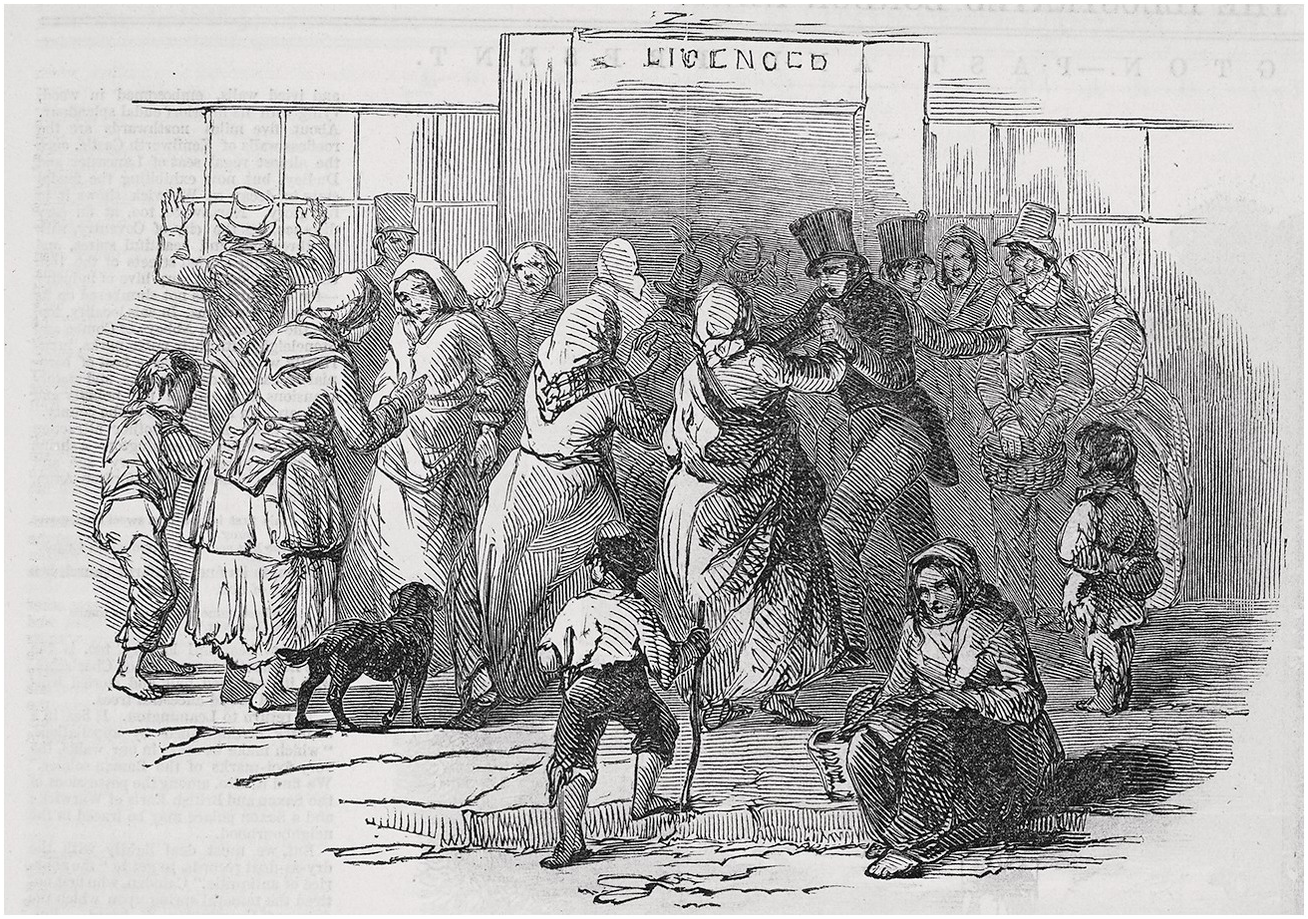

At the beginning of 1847, the Central Relief Committee (CRC), which had been formed as a Quaker umbrella organisation for Ireland, opened a model kitchen in Dublin that sold an average of 1,000 bowls of soup daily until the end of July, when complimentary government provisions had curbed the demand. In the Quaker shop, one penny gave the poor a quart of soup, and another halfpenny added bread. Nearly 50 per cent of the rations ‘sold’ were purchased with coupons from benefactors who distributed them among the poor at their own discretion (see Figure 4.2). The CRC supported in its efforts by a local collection covered more than one-third of the expenses. They reported frequent visits by observers from similar establishments across the country who wanted to study their operation.Footnote 57

Figure 4.2 Famine tokens, 1846/7.

The CRC helped in the establishment of such soup facilities by others, assisting with boilers and money, and importing provisions. They emphasised the many grants that they had given to women, whom they regarded as their most efficient social workers, and regretted their want of proper stores and reliable agents. The storage problem and the trouble of arranging transportation within Ireland were solved in connection with the goods sent to the CRC from the USA throughout the spring and summer of 1847. Modelled on an arrangement with the BRA, the government allowed the CRC to transfer incoming supplies to the nearest commissariat depot (at public expense), crediting these shipments at their current market value. The sum could then be used to pick up foodstuffs from any other government depot. This system, based on a substructure of escorted food transports along waterways and major roads (railways were still in their infancy), lasted until late summer, by which time the depots were empty. The CRC then sold aid supplies that continued to arrive and used the proceeds as discretionary funds.Footnote 58

The government itself turned to soup kitchens as the cheapest way of feeding people and as ‘economising our meal’, in the sense of offering the best possible nourishment with limited funds.Footnote 59 Medical experts provided advice regarding the comparative nutritional value of different foodstuffs (which was to be considered when comparing prices) and the necessity of a varied diet.Footnote 60 Soup kitchens also solved the problem of sweetcorn consumption, with which the Irish were unfamiliar. Another major advantage of a soup facility was that a simple ‘indulgent’ administration sufficed, as a person presenting themself for a meal which they receive in their own mug served as a means test to ensure the neediest were being served.Footnote 61 According to a contemporary assessment, serving cooked food, compared to handing out staples for home preparation, reduced the number of claimants by more than one-third, suggesting issues of pride and accessibility.Footnote 62 In addition, soup kitchens provided jobs for women.Footnote 63 However, according to one report, preparing so much soup brought about a ‘great slaughter amongst the poor people’s cows’. Thus, adding meat to the soup, due to the urgency of the moment, unfortunately deprived the same people of milk and butter.Footnote 64

The government wanted to have the ‘soup system’ run by relief committees operating across Ireland by the beginning of 1847. However, officials realised that any scheme depending on voluntary contributions would be inadequate to sustain the starving population.Footnote 65 Nevertheless, as the public works programme became increasingly dysfunctional and threatened to interfere with the sowing season, soup kitchens were seen as a viable alternative. In February, Parliament adopted them as a way to feed up to three million people on a daily basis. Thus, between May and September 1847, the self-defined ‘night watchman state’ demonstrated its logistic capacity.Footnote 66 According to the analysis of Skibbereen’s physician, Daniel Donovan, not only had the public soup act provided people with essential nourishment, but it had also proved to be ‘the best cure for Irish fever’, as the often deadly famine diseases were then called.Footnote 67 The soup programme was not only appreciated in Ireland at the time; today there is widespread agreement that it provided the most effective transfer of entitlements. It is also believed that had it been implemented over a longer period, it would have significantly lowered mortality. However, the provision of soup, offering subsistence without requiring any return in labour, and with only the minor discomfort of having to consume one’s meal in a public place, was incompatible with the austere moral economy of UK elites. It was, therefore, restricted to a seasonal measure that was to terminate with the upcoming harvest.Footnote 68

The BRA’s role in this connection was to prepare for the policy shift from public works to the government-sponsored feeding programme. They were to make foodstuffs available in the remote south and west, particularly in kitchens set up by local committees. With the implementation of the government soup act in May 1847, voluntary aid was shut down.Footnote 69 As the BRA only accepted as partners relief bodies that adhered to official guidelines and submitted their applications through government officers, it reinforced state control of local charities, which was also based on the match-funding of voluntary collections with public grants (after mid-December 1846, such grants had been doubled, occasionally tripled).Footnote 70

Fundraising for Ireland at the beginning of 1847 inspired Alexis Soyer, Victorian London’s celebrated French chef, to create a soup based on food science to provide maximum nutrition at minimal cost, and to raise funds for a model kitchen. The government was interested in Soyer’s plan and provided him with a soup house in Dublin that had been designed for mass feeding. It incorporated calculated flows of people, spoons chained to the tables, and a rigorous time regime – anticipating later shop floor management.Footnote 71

Some of the local press described the opening ceremony, at which high society congregated with the suffering poor, as an imperial spectacle that subjected the latter to a ‘pitiless gaze’, outraging ‘every principle of humanity’.Footnote 72 For a five shilling admission fee, one could watch charitable ladies serve paupers food. Although the proceeds were put to good use, a newspaper condemned the procedure as akin to the inspection of animals in a zoo at feeding time. Nevertheless, it was hoped that the fees collected would be of some benefit to those ‘beggar-actors’ whose humiliating performance had raised them.Footnote 73 Whatever one may think of Soyer’s moral balance or his recipes (which included oysters, a cheap food at the time), his combination of applied science, personal showmanship, and spectacle for donors transcended nineteenth-century philanthropy and perhaps the Irish context. A British officer in Dublin commented at the time that, while Soyer would be successful anywhere in the world, his success was impossible to foresee, as the Irish were ‘a strange nation, they hate every thing new, and they must have any change thro’ their own people and in their own way’.Footnote 74

The Quakers created a soup distinguished by a high proportion of meat – six-fold that which was called for in Soyer’s recipe.Footnote 75 However, like government aid, most Quaker relief ceased by late summer 1847, or took on other forms. When faced in early 1848 with the question of whether to reopen their soup shops, the Quakers found that people in the surrounding area were too exhausted to serve as organisers and workers in such a project. Despite the Quakers’ charitable tradition, the CRC emphasised that they had no experience in the humanitarian undertaking upon which they had embarked, and that the underdevelopment of Ireland posed its greatest problem: the country lacked a middle class able to administer relief and a commercial infrastructure for the distribution of food. The organisation eventually spent some of its funds for development projects, conceding that using money raised for emergency relief to fund a permanent object posed an ethical dilemma.Footnote 76

Money and Aid-in-Kind

British charity in the 1840s favoured the distribution of aid-in-kind. In the USA, the abundance of grain resulted in the adoption of a similar policy, making a virtue – providing humanitarian aid – out of a necessity – getting rid of agricultural surplus. Both countries shipped much needed provisions to Ireland. Staple foodstuffs were sometimes sent directly by their producers.Footnote 77 Collections, particularly in religious communities, resulted in donations of jewellery, clocks, a marble statue of the blessed virgin, and other such items, although they were not always readily convertible to cash. After a few weeks of such collection, the Irish College in Rome estimated it had received up to £300 worth of precious objects.Footnote 78 However, a diamond ring that was said to cost £100 in England could only be sold for £20 in Rome, and so (like the marble statue) was forwarded to Dublin in expectation of a better price.Footnote 79 It is unclear whether the offer of 2,000 cubic palms (37 m³) of fine breccia Gregoriana marble, to be sold in Italy or Ireland, ever was accepted.Footnote 80 At the same time, worthless devotional items were forwarded to the Vatican, since they were believed to ‘demonstrate great charity’.Footnote 81

Most importantly, there were separate collections of clothing. Alongside money, second-hand apparel played a large role in charitable drives, although some of it was likely to join the original clothing of the beneficiaries in a pawn shop. With reference to such divestment, an Irish landlady suggested that ‘whatever clothing is sent, ought to be of a very peculiar pattern or colour, and marked in a very conspicuous way, so as to be unsaleable’.Footnote 82 Necessity also led to the reuse of empty food sacks as material for making clothes.Footnote 83

Most inedible gifts had to be converted into cash to be of any use. The provision of aid was thus dependent on financial transactions and frequently on valuta exchange. Sometimes this involved consecutive operations, such as when the Vatican gathered funds in various currencies and sent the proceeds to Ireland. At the same time, the notion of round sums or specific collection results clashed with the market principle, where fixed wholesale quantities of foodstuffs were traded at constantly fluctuating prices.Footnote 84

While most relief monies were used for the purchase of supplies, cash was occasionally given directly to recipients in distressed Irish localities in order to strengthen their buying power, as Sen would later also recommend. Although these sums were too small to have any significant effect on the importation of food, the entitlements enabled individuals to meet their own needs for sustenance or help some of those around them. Money was a decentralised and flexible form of relief, flowing through a variety of direct and indirect channels.

Such relief typified how churches in the Irish homeland forwarded domestic and foreign donations. Aid arrived at all levels of the hierarchy, although larger amounts and contributions from distant lands were often received at the highest level. Thus, the Catholic prelates of Ireland became recipients of funds conveyed to them for use either at their own discretion, or as earmarked sums. Church officials are also said to have significantly contributed from their own pockets.Footnote 85 Generally, the four archbishops of Ireland divided the money they received among the country’s twenty-four bishops, who passed it on to more than 1,000 parish priests and heads of church institutions. For more rapid dissemination, the archbishops also provided aid directly to the local clergy.Footnote 86

Vertical distribution was complemented by a horizontal plan. Daniel Murray, archbishop of Dublin, and William Crolly, primate of all Ireland and archbishop of Armagh, were often charged with distributing Catholic welfare across the country. Both transferred funds designated for Catholic distribution to Michael Slattery and John MacHale, their colleagues in the most afflicted sees of Cashel and Tuam in the south and west of Ireland. They were praised for the fairness with which they shared incoming aid.Footnote 87 However, both Murray and Crolly were politically conservative, prioritising interdenominational co-operation in their approach to famine relief. They feared that targeting aid towards Catholics ‘would seem to the public as too exclusive, and as having but little of the spirit of the good Samaritan in it; and perhaps even cramp the benevolence of protestants to us’, or, even worse, serve as a model for ‘other influential persons, who will refuse to give relief to the Catholic poor’.Footnote 88 They, therefore, tended to forward those donations that were not explicitly designated for Catholic distribution through broader relief channels.Footnote 89

Although such diversion of ‘Catholic money’ was internally controversial and at times criticised in the press,Footnote 90 no open dispute arose. Murray had handed over the collection of London Catholics to the GCRC, where he was a key figure.Footnote 91 He hoped the same distribution would be done in the case of Vatican collections, but ultimately yielded to Slattery and MacHale, who challenged the ‘great tendency to set aside the bishops in favour of mixed boards and government officials’.Footnote 92 Cullen later asserted from Rome that the Vatican had hoped for distribution through the Church and that they were glad the donation had not been allowed to pass into ‘government management’.Footnote 93 However, some bishops did forward money to local relief committees, rather than to their priests.Footnote 94 Parish priests were the customary recipients of money grants by the GCRC, but were expected to see that distribution took place across denominational lines. In many instances, the channels that were used are unclear, since the secretary of the GCRC was simultaneously involved in distribution through the Catholic hierarchy.Footnote 95

Parish priests gave the alms that they received to the poor of their flocks and to other sufferers at their own discretion. The extent to which they did this by means of money, food coupons, and material aid such as foodstuffs, clothes, and even coffins is unknown. In any case, the cash flow did sometimes reach those suffering from hunger. At the same time, there are many reports that people stopped using coffins during the famine, or adopted a frugal variation with a hinged bottom that made it reusable, illustrating the descent into a moral economy of survival.Footnote 96

Whereas Vatican instructions generally took a needs-based approach to relief,Footnote 97 its own disbursement among Irish prelates went from providing centralised aid to dealing personally with bishops and certain monastic and ecclesiastical institutions. Although the intention of aiding the most distressed areas remained, the actual distribution showed moral support for all of Ireland and reflected regional differences in suffering to a lesser extent. For example, the money the Holy See sent between April and July 1847 benefitted each of the Irish bishops and archbishops, the former in the amount of £50–150, the latter ranging from £150 to £300.Footnote 98

The Comité de secours pour l’Irlande had a more targeted approach, initially focusing on the most afflicted sees of Cashel and Tuam. However, on recommendation of Redmund O’Carroll, president of the Irish branch of the Society of St Vincent de Paul (SVP), the Comité included five northern dioceses to their list of beneficiaries, applying a formula according to which 40 per cent of their funds went to the south, 30 per cent to the west, and another 30 per cent to the north of Ireland.Footnote 99 Thus, they took into account the fact that the provinces around Dublin to the east were not a major famine area, but they did distribute aid to the less affected north of Ireland. The French reliance on a single informant illustrates the problem of making rational allocation decisions from a distance.

By contrast, SVP donations supported existing and newly established branch organisations that were mainly in Dublin and the south of Ireland. They were part of an effort at the time to roll back the ‘New Reformation’ in Ireland. The choice of certain rural locations for SVP expansion, like Dingle and West Schull, was geared to counter the evangelical ‘traffickers in human souls’ there, as was claimed.Footnote 100 In Schull, the Congregation of the Mission encouraged the establishment of an SVP chapter ‘with a promise of pecuniary aid’ from SVP headquarters in Dublin.Footnote 101 Dingle also received regular allotments from the Vatican.Footnote 102 Catholic donors showed particular interest in places where there was religious rivalry and the presence of ‘Soupers’, as Protestant proselytes or proselytisers were called because of their alledged trade in faith and food. However, even the Catholic Church began to use food as a tool for securing its flock and winning back ‘perverts’.Footnote 103 Such food conflicts tended to arise in impoverished locations, although sectarian competition in a country strongly divided along religious lines and with a dominant Protestant minority culture was a factor.

Efficient and safe ways of forwarding donations was a frequently discussed issue. Sometimes, cash was simply carried from one place to another. For example, the Irish College in Rome recruited a student who was returning home, to carry thirty-four silver medals back to Ireland.Footnote 104 In general, funds were conveyed across borders by bills of exchange (see Figure 4.3). However, this well-established method had its drawbacks. Bills of exchange presupposed brokers, trustworthy networks, and maturity periods that delayed the disbursal of relief funds.Footnote 105 As financial institutions abroad often had no commercial relations with Ireland, transactions were frequently conducted through London banks.Footnote 106 This roundabout method occasioned additional costs and time delays. Bills of exchange also depended on the proper working of two financial systems. A recipient of French aid via a bill of exchange had to postpone cashing a voucher for two weeks because the ‘pressure for money’ was so great in Dublin that the face amount could not be obtained on its stated due date without incurring a substantial bank fee.Footnote 107 That the recipient in this case chose to wait two weeks for the full amount shows that the larger sum was of more value to him than receiving less money immediately, despite the high mortality rate at the time.

Within Ireland, relief funds were often transferred by postal or bank money order, a system that apparently worked well. Complaints, like a rector’s grievance that the Skibbereen post office was out of cash for a period, or the Dingle Presentation Convent’s problems with receiving the donations sent to them, were exceptions.Footnote 108

While foreign banks generally profitted from transactions involving relief funds, the BRA was governed by a ‘cabinet of bankers’ based in London who offered their services gratis.Footnote 109 English Catholics used the Commercial Bank, which also appears to have provided its assistance at no charge.Footnote 110 The same was true of the Paris-based bank of Luc Callaghan, used by the Comité de secours pour l’Irlande, and of the SVP’s bank, which charged neither commission nor exchange fees.Footnote 111 There were also banks in Ireland that transferred money for the relief of the poor at no cost.Footnote 112 The trustees of the Indian Relief Fund thanked the directors of the Bank of Ireland for cashing their bills without charge, ‘although at six months date’.Footnote 113 Thus, in many cases, transaction costs for aid agencies were minimal due to the free provision of bank services. This is in agreement with attempts to keep overheads low. Examples of private support are free rent for relief organisations, not charging for labour,Footnote 114 no commissions, and not seeking profit, while government subsidies were generally reimbursement for transportation costs. In addition, the government contributed to reduced transaction costs by making its food depot infrastructure available to private charities.

Domestic and Overseas Migration

Aid efforts, whether public or private, set people in motion, with both desired and unintended consequences. Some soup kitchens distributed food by cart in their neighbourhood. Invalid’s diets were sent to the homes of the sick, anticipating modern ‘meals-on-wheels’, although finding volunteers who dared to go near the sick was a challenge.Footnote 115 Despite such services, the soup kitchen model generally required people to line up and sometimes walk long distances for a daily meal, which presupposes greater mobility than a monetary distribution system.

The conviction that ‘people for distances round will come in to partake of the benefit’ functioned as a means test, but also caused an uprooted population to resettle wherever aid was available.Footnote 116 Thus, whereas the overall population of Ireland sharply declined during the Great Famine, the four largest cities continued to grow.Footnote 117 Even a ‘“relief” town’ – as a contemporary journalist called it – like Skibbereen experienced a continuous influx from the countryside that stabilised the total number of inhabitants in the winter of 1847, despite exceptional mortality.Footnote 118 Locals complained that the misery of their town was multiplied by the paupers who flocked in from surrounding areas.Footnote 119 Similarly, benevolent circles in Cork were alarmed by Skibbereen sending its poor over to their city. The suspicion that charitable funds were misappropriated in hiring carriages to dispose of the destitute caused particular indignation. It made a newspaper demand (and receive) a ‘strong and unequivocal contradiction’ of such an ‘ungrateful return’ by a people who owed much to Cork and the regional press.Footnote 120 Further up the aid chain, British philanthropists also felt ‘ungratefully treated’ when they learned that Irish relief committees were shipping their destitute to them.Footnote 121

Skibbereen played a conspicuous role in the exportation of misery, with an elaborate scheme reflective of their moral economy. The three target groups for their emigration programme were healthy men seeking work, women and children who had someone in England who could maintain them, and elderly people of Irish background unjustly returned by British authorities ‘for support on a people who never derived any benefit from their labour’.Footnote 122 In a Letter to the Editor, accounting for the donations entrusted to him, Townsend declared that he was to give £5 ‘towards helping a few heads of families to go over to England to shew the Times that Paddy loves his good English fare too well not to go there when he can, and earn for his poor, empty, hungry stomach some of his bread and cheese, and take a crotchet out of his gamut’.Footnote 123

Some Skibbereen emigrants were sent by coach via Cork to a steamer headed for London, but most embarked directly at the local County Cork harbour of Baltimore. Two individuals established the emigration scheme by the end of November 1846: Donovan, who used the income from his workhouse vaccination contract to redeem indispensable clothing from pawn and buy biscuits for the journey, and a ship and mill owner who provided free passage to Newport, South Wales. Adverse winds, a captain who fell ill, and provisions that were only enough for seven days made one of the first ships, carrying 113 paupers, strand near Cork. After a five weeks journey, the ‘floating pest-house’ reached its destination, five of its passengers dying upon arrival. The journey also generated one of the few reports hinting at sexual exploitation by relief workers during the Great Irish Famine. The mate and the sailors on the ship, while otherwise treating passengers unkindly, were said to have ‘become familiar with some of the girls, whom they took with them to the forecastle’. Sustaining the newcomers became an additional task for the Newport Irish Relief Fund.Footnote 124 Such problems were not reported from other Skibbereen ship passages, but the misery of Irish emigrant ships in the North Atlantic during the late 1840s was notorious.

When the steady flow of emigrants became known to the administrator of the Skibbereen food depot, he reported that funds designated for poor relief were being diverted for the shipment of ‘wretched naked creatures’ to England and Wales.Footnote 125 While landlords in many cases were glad to defray the emigration expenses of their tenants, and although there was a general suspicion that relief committees were shipping their clients off to Liverpool, the account from Skibbereen was exceptional in suggesting an actual misappropriation of funds.Footnote 126 A later investigation into the ‘deportation of paupers’ from Skibbereen to England concluded that public monies had not been applied.Footnote 127 However, the police report on the matter reveals a local enterprise with semi-official traits: Donovan had privately received £10 from the poor law guardians, which he used together with money of his own to send 500 paupers from Skibbereen and its surrounding areas to England. A private shipowner had gratuitously supplied two vessels for this purpose, and the government commissary provided a supply of biscuits for the passage at cost.Footnote 128 The fact that Donovan was a prominent, well-thought-of relief worker, whose diaries with glimpses of the distress in Skibbereen were circulated widely in the press, may have caused objections to how the exodus was financed to be dropped.

The migration of paupers and others from Ireland affected England, the British dominions (particularly Canada), and the USA. The influx of famine refugees launched relief operations wherever they disembarked. It also resulted in criss-cross migration, as poor-law unions in England deported Irish paupers back to their origin. The GCRC, which otherwise disregarded Dublin, made a special £400 grant to the lord mayor of Dublin on their behalf.Footnote 129

Liverpool was greatly affected, as large numbers of famine refugees poured into the city until 1853. In 1847 alone, more than 116,000 paupers arrived from Ireland, in addition to more than 180,000 transmigrants to North America (the cost of passage to the New World being a maximum of £4). It is estimated that 5,500 famine refugees died of typhus, dysentery, and diarrhoea in Liverpool that year, making the city known as the ‘cemetery of Ireland’. The epidemics spread by disease also raised the mortality rate among other sectors of the population.Footnote 130 Estimates of deaths in Great Britain brought about by the Irish Famine range from 10,000 to 15,000 for the year 1847 alone, to 150,000 for the late 1840s.Footnote 131 A Cork newspaper recognised the generally kind reception that refugees received in English towns, which it interpreted as a gesture of appreciation: ‘The Famine that has driven swarms of our people to Liverpool for instance has enriched its merchants; their [export] profits upon food consumed in Ireland might be reckoned by the million.’Footnote 132 Even in inland cities such as Birmingham, collections for those back in Ireland competed with the needs of Irish newcomers in English towns – something that especially affected the Catholic communities. Thus, in the beginning of February 1847, 200 refugees were being cared for daily at the bishop’s house, and many others at the convent.Footnote 133 The poor families aided at the time by English branches of the SVP were mainly Irish.Footnote 134

In North America, famine migration also caused donors to open their doors to the new arrivals. As fares were lowest to Canada (as little as £1½), ships bound there were greatly overcrowded and wretched.Footnote 135 In Quebec, approximately one-sixth of all passengers who came ashore from Ireland in 1847 died shortly after arrival. Many more had already perished at sea. Grosse Île, the quarantine station for those entering Canada, was unprepared for the mass influx of migrants and became a symbol for the plight of the famine refugees.Footnote 136 Charitable Irish societies assisted the newcomers in many places, and new societies such as the Hibernian Benevolent Emigrant Society of Chicago or the Irish Emigrant Society of Detroit were founded in response to the famine migration.Footnote 137 However, the social and medical problems caused by this influx also called forth an estrangement between the refugees and their host population that contributed to the drying up of transatlantic charity during the latter part of 1847 and to tightened immigration policies.Footnote 138 Strum suggests that, in hindsight, various leaders of Irish famine relief appear to have developed hostile attitudes and turned into nativists.Footnote 139 In many ways, nineteenth-century society in the UK, Europe, and the world at large was unprepared for the sustained relief effort that would have been needed to significantly mitigate the Great Irish Famine, thus illustrating the limits of ad hoc humanitarian efforts.

4.3 Live and Let Die: Soviet Russia

Providing famine relief in Soviet Russia between 1921 and 1923 posed a multitude of challenges to foreign organisations. Concerns about the misuse of aid, paralleled by the inevitable necessity of collaborating with Soviet agencies, made more difficult a situation that was already financially and logistically complicated. Continuous negotiations with Soviet authorities were necessary during the whole operation to keep things running smoothly. This often led to conflicts, especially on a local level, partly because of personal and ideological animosities and mistrust, and partly because details of the 1921 Riga agreement were unknown in the Russian provinces.Footnote 140

Apart from control of distribution, a major concern of organisations providing foreign relief to Russia was logistical questions. There was hardly enough capacity in the Baltic ports to unload large cargoes. Moreover, they were blocked by ice all winter, so that Black Sea ports had to be used instead. The Russian railway network was in disrepair. A transport from Riga to the famine region of Saratov was estimated to take fifteen days, but in December 1921 took thirty days. In February 1922, travel came to a complete standstill due to weather conditions and fuel shortages.Footnote 141 The train system proved to be a bottleneck in relief operations, no matter how well planned, and conflicts arose between different organisations about cargo space.Footnote 142 During the winter season, many areas most severely affected by the famine could only be reached with sleighs drawn by horses or camels. A trip of under 300 km could take up to seven days. In many famine regions, more than 90 per cent of the livestock had died, so that even this outmoded form of transportation was often unavailable.Footnote 143

As organisations sought to keep the number of their staffers as low as possible, each fieldworker – mostly young and often unprepared for the job – had to shoulder an enormous workload and great responsibility. A number of the men (only Quakers accepted female relief workers) experienced what was referred to as ‘famine shock’ when facing the horrors of starvation. Several cases of nervous breakdowns and alcohol abuse ensued.Footnote 144 In addition, poor hygienic conditions – trains, for example, were described as ‘lice-infested death traps’ – impeded operations and threatened aid workers’ lives.Footnote 145

Those who were responsible for planning and coordination went through a similar collision with reality. Their previous work in Central and Eastern Europe made them profoundly underestimate the gravity of the situation in Russia. What had been planned often proved unrealistic and inadequate. The idea of concentrating the distribution of food in big cities – presupposing that refugees would flock there – was revised after representatives of the organisations began operating from the country and sent in their reports from the Volga area (see Figure 2.2).Footnote 146 When Hoover, in answer to Gorky’s appeal, committed to feeding one million children, he assumed that each Soviet citizen was receiving a daily, state-financed meal, so that a supplementary ration would suffice. It was only during the Riga negotiations that this misunderstanding was corrected.Footnote 147 The Save the Children Fund (SCF) also realised that the portion distributed was often the only food people would eat that day. Their general plan of systematic feeding had to be adjusted when they learned this and other facts on the ground.Footnote 148 Attempts were made to take current research into account and prepare meals constituting a balanced diet. However, it was practically impossible to arrange such things as individual nutrition cards and customised diets. Methods of assessing the degree of malnutrition, like the Pelidisi table that had been tried in Central Europe, could seldom be applied under Russian conditions: there were too many victims, too few doctors, and a lack of time.Footnote 149

Organising Famine Relief

When planning and distributing aid to Russia, organisations drew on their prior experience in European relief operations after the Great War, and on British imperial expertise battling famines in India. Hoover continued to support the European Relief Council (ERC) that had united major US aid agencies during post-war operations under the banner of the American Relief Administration (ARA) as the main distribution entity. He favoured forms of allocation that were tested and proven, including a warehouse and kitchen system, the establishment of local committees to provide assistance, and the food remittance programme. The British colonial system of famine relief helped coordinate various agencies across large territories and the spatial organisation of relief centres, both of which were effective under Russian conditions.Footnote 150 The British also took a ‘Victorian approach’ to aid that was similar to ARA relief ideals and can be summarised as ‘keep[ing] people alive without making them dependent’. Accordingly, former colonial administrators, like Sir Benjamin Robertson and Lord George Curzon, as widely respected famine experts, influenced not only the work of British agencies, but also that of the ARA and Nansen’s International Committee for Russian Relief (ICRR).Footnote 151

The famine region was divided early on in order to avoid under- and over-supply. The ARA appointed more than a dozen district supervisors, each responsible for a specific area. Organisations like the SCF and the Quakers worked in the same manner, but on a much smaller scale. For example, SCF established ten sub-bases, headed by British supervisors, in villages and small towns around its headquarters in Saratov.Footnote 152 Communication between districts and headquarters took place via cables and letters. The ARA set up its own carrier service, paralleling the Russian postal service, and would transmit more than 50,000 telegrams during the relief operation.Footnote 153

Distributing agencies further divided the afflicted area into spheres of influence. This forestalled conflicts and enabled smaller organisations to retain a certain independence, something that was valuable in their fundraising and public relations campaigns. Thus, the Saratov province was divided between the ARA, on the one hand, and the SCF and the International Save the Children Union (ISCU), on the other, giving the USA responsibility for the zone east of the Volga, while the Europeans took the western part. The Quakers proceeded in a similar way in their assigned territory in the Samara province: after a split backed by Hoover, British Friends covered the western part of the Buzuluk District, while the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) took over the eastern part, receiving their supplies from the ARA.Footnote 154

Such zones of influence had to be adjusted to new conditions from time to time. When British Quakers extended their adult feeding programme in 1922, the ARA supported them and concentrated resources accordingly. Similarly, when a Swedish Red Cross (SRC) team arrived in Samara in December 1921, the ARA, which was already present, assigned them a specific field of operation, extending it in the months that followed as Swedish resources increased.Footnote 155 For the ARA, in its role as the main distributing agency, such co-operative agreements meant that resources could be saved. However, moral dilemmas also arose, when smaller actors fuelled expectations, which they were not able to meet. For example, when the Volga Relief Society (VRS) withdrew from the Saratov province in September 1922, an ARA officer reported that he now felt ‘morally bound to continue support to the German colonists’ whom the VRS had aided before.Footnote 156

A decentralised system of distribution, as well as the establishment and provisioning of camps and hospitals for refugees, was also meant to forestall, arrest, and reverse migration from villages to towns, and from the Volga region to Ukraine and Siberia. The ‘imperial anxieties’ of ‘famine wanderers’ were evident in the recommendations of former colonial administrators,Footnote 157 but a cover of the journal Soviet Russia showed similar concerns. Beneath a poster depicting hungry peasants heading westwards, a caption explained that the Friends of Soviet Russia (FSR) sent food and tractors ‘in order to maintain these masses at their post’.Footnote 158

A widespread net of warehouse and food depots also proved necessary, since any interruption of supply was generally due to transportation difficulties. In fact, transport was the biggest problem at the beginning of the relief operation, and it prevented an early extension of the feeding programme. The distribution of reduced rations to a greater number of people had been considered, but it proved infeasible, as the ration being provided already constituted an ‘irreducible minimum’. The chief of the SCF operation in Saratov described how warehouses in Riga were stocked to full capacity in late 1921 ‘as far as financial means were available’ because it was expected that the port would be inaccessible during the winter months. In the Volga region, winter threatened to cut off the supply to the most affected areas, where the population depended on river transport since they were far away from railheads. Depots there were stocked as much as possible in order to guarantee an uninterrupted supply of food. It was equally important that provisions be balanced, that is, ‘the correct proportion one to another of different foodstuffs required for our menus’.Footnote 159

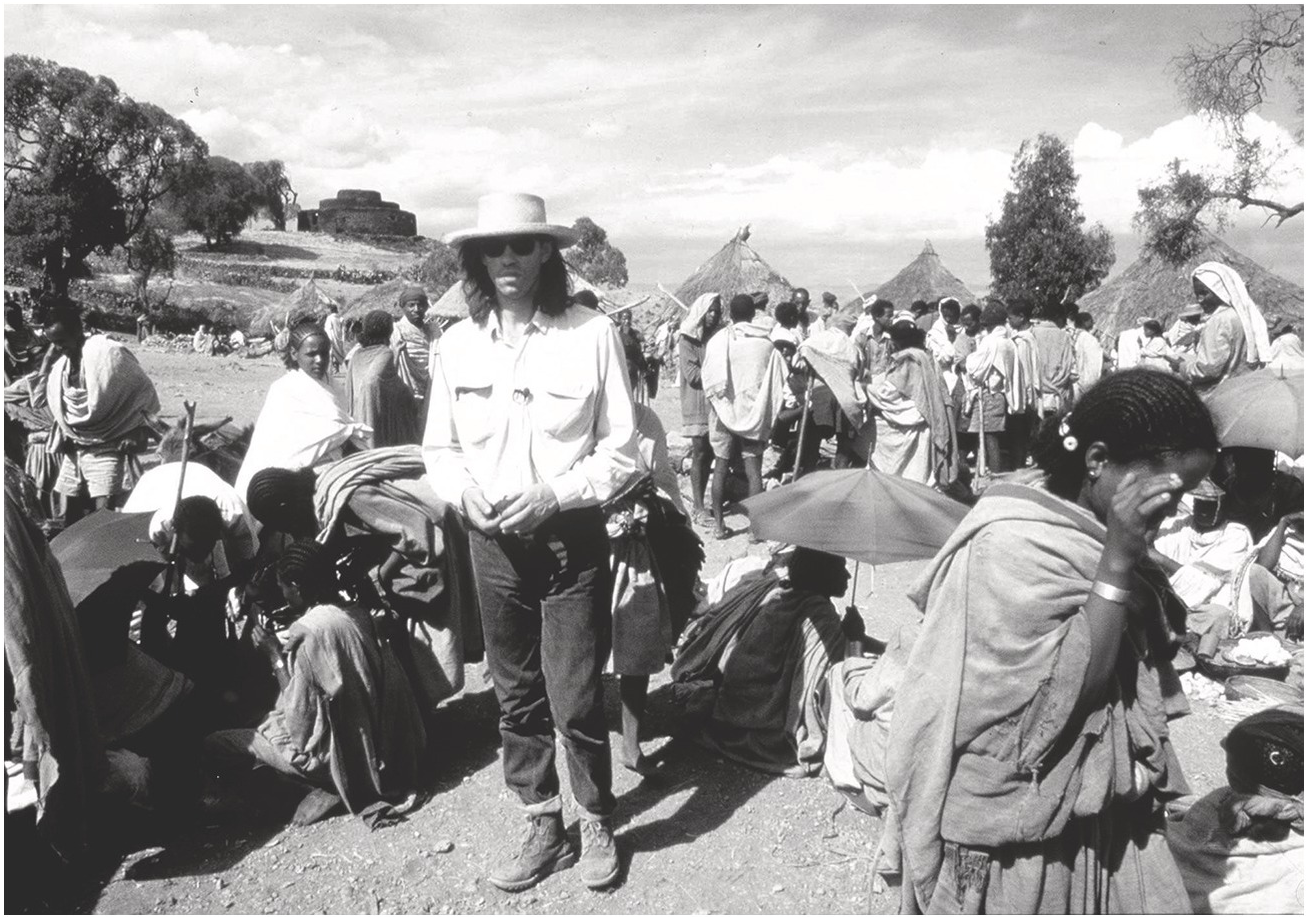

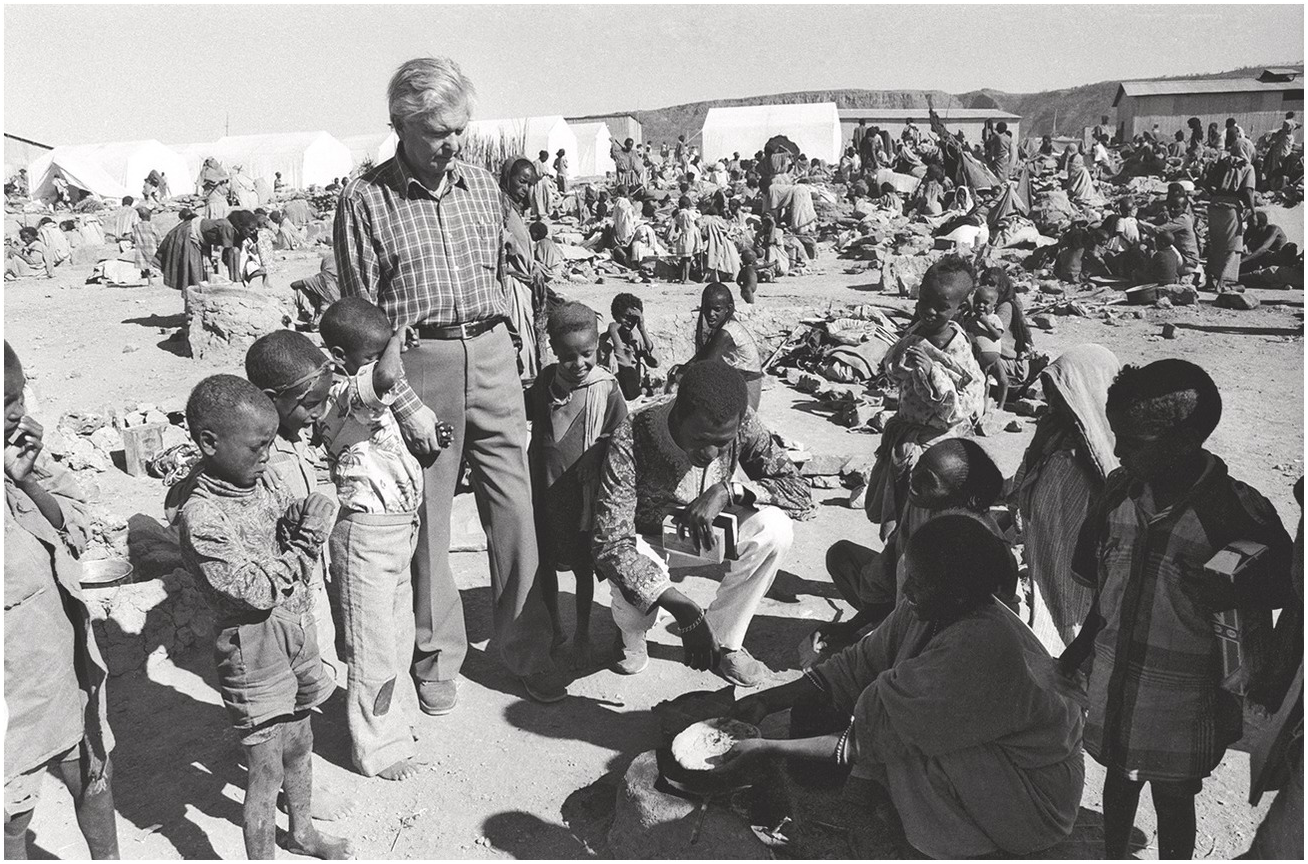

The ARA food remittance programme, a further development of its popular and successful food remittance programme that had been used in Central Europe, was introduced in October 1921 as an alternative instrument of famine relief. People outside Russia could donate a food package with a US$10 remittance at any ARA office (see Figure 4.4). Needy individuals or groups in Russia could then collect the parcels from a local ARA warehouse.Footnote 160

Figure 4.4 Packing ARA food remittances in Moscow, 1922. In contrast to previous remittance programmes, food parcels were now packed in the affected country.

Initially, Soviet officials mistrusted this form of relief, as they had little control over the beneficiaries. They feared that people with relatives or friends abroad (who were already suspect for that reason) would profit, whereas committed communists may be left empty-handed. In addition, parcels might be used for speculative transactions. To prevent that, a limit of five parcels for individuals and fifty for groups was imposed, and each addressee had to sign a form stating that they would not sell any of the contents.Footnote 161 Donors were told that the estimated US$2.25 per package profit from the food remittance programme would be invested in a child relief campaign. Another positive argument was that the availability of more food – whether or not it was received by a needy person – would lead to an easing of the local market.

However, critics voiced moral concerns that such a programme might result in an unjust distribution of relief. For example, Jewish organisations and individuals were over-represented on the private donor side, which meant that regions in Ukraine and Belarus with large Jewish minorities would receive a substantial share of the packages.Footnote 162 In order to organise the distribution, the ARA had to build up delivery stations in these regions, although some were technically outside the famine zones.Footnote 163 ARA supervisors in districts where few people had emigrated to Europe or the USA in the decades before complained that inhabitants received no food parcels simply because they had no kinship connections beyond Russia. Thus, the ARA was forced to supply these areas with more general food aid.Footnote 164

While organised robberies and large-scale embezzling were exceptions, internal reports and anecdotal evidence reveal many incidents of diversion.Footnote 165 These included thefts by harbour and transport workers, desk clerks demanding illegal charges for releasing remittances, Russians claiming the rations of dead relatives, attempts to obtain parcels with falsified documents, local committee members giving family and friends advantages, kitchen personnel eating food intended to feed children, and the seed grain being consumed as food.Footnote 166

Some relief workers were also operating for personal gain. Already in December 1921, an ARA officer noted that employees were ‘purchasing furs, diamonds and other things, evidently with an idea that they will personally profit by these investments’.Footnote 167 In February 1922, Soviet authorities thwarted an ARA employee’s attempt to smuggle several kilos of gold and twenty-six carats of diamonds out of the country. While an incident involving goods of such high value was exceptional, this was not an isolated case.Footnote 168 In view of the widespread habit of relief workers using their salary to buy valuable goods at bargain prices, a pro-communist US journalist questioned ‘whether the millions of loot they are taking out of the country isn’t more than their relief’.Footnote 169

Having a privileged position also brought social advantages to foreign relief workers. In Moscow and Petrograd, ‘plebeian Americans of no importance at home’ gained the status of celebrities, as an ARA observer noted.Footnote 170 Numerous relief workers carried on intimate affairs with local women, relations that could entail sexual exploitation. An older ARA man commented prosaically that ‘one does not have to pay much for women who are starving and some of our boys are making the most of the market’.Footnote 171 No less than thirty ARA men married during their service, most of them bringing their ‘famine bride’ back to the USA.Footnote 172 Nansen’s representative in Ukraine, the later Norwegian Nazi leader Vidkun Quisling, married two women during his tour of humanitarian service, one of them only 17 years old.Footnote 173

Kitchens and Food

In urban centres like Saratov, warehouses and a basic kitchen infrastructure were already in place when the foreign aid workers arrived. It was reminiscent of earlier years when parts of the population were fed in public kitchens.Footnote 174 However, the situation in the cities was not as devastating as in the surrounding rural areas. Robertson, after his inspection of the SCF feeding programme, observed that 35,000 of the 250,000 children being supported were city residents. He proposed that this number be reduced and the resources be better used in the countryside.Footnote 175

The kitchens run by ARA, SCF, the Quakers, and other organisations including Soviet authorities varied in size. They were feeding between two dozen children per day in some villages, and several thousand in larger cities. In the Saratov region, the SCF had approximately 400 kitchens by January 1921, serving an average of 500 children.Footnote 176 The staff in many kitchens, was compensated in part on a commission basis, receiving a stipulated number of rations for themselves after they had fed a specific number of children. Other Russians employed by foreign organisations often received parts of their salary in the form of food as well, a so-called paiok.Footnote 177

When provisions finally reached the famine regions, often far behind schedule, ‘much ground [still had] to be covered before the food could enter the children’s mouth’.Footnote 178 As feeding everybody was impossible, lists dividing famine victims into different categories were made, a practice adopted from colonial experience.Footnote 179 ARA, SCF, and the Quakers co-operated with local committees for that purpose, but recruiting reliable agents in Russia was sometimes difficult. A considerable number of the local elites had vanished in the social upheavals of the revolution or because of the famine; others suffered greatly from hunger themselves. Unlike in Poland and Hungary, it was difficult to find individuals in whom the population, the relief organisations, and the authorities would place their trust.Footnote 180

The ARA sought to influence the make-up of these committees, a right they had fought hard for during the Riga negotiations, where Soviet representatives vehemently opposed this request.Footnote 181 Determining who was on the committees was important to prevent abuse and make sure that relief goods were targeted ‘without regards to politics, race and religion’, and to silence critics at home. The SCF, however, assumed that the compilation of detailed lists and the organisation of single food kitchens were ‘of course … done by the local authorities’.Footnote 182 Robertson indicated in his report that the Russian recommendations regarding those who should be fed must be verified, ‘but the numbers are so large that Mr. Webster [Laurence Webster, head of the SCF operation] has practically to take it on trust that the Committee recommends the most deserving cases’.Footnote 183 Meanwhile, SCF officials limited themselves to functioning as a ‘court of appeal’ in cases of complaints.Footnote 184 A regular inspection of all kitchens was impossible due to a lack of personnel; both the SCF and the ARA employed Russians for this task. Unannounced inspections and the threat to immediately close any institution that was badly run proved to be ‘the most effective weapon of control’.Footnote 185

In the case of SCF relief, each child selected was given a ticket for two months, with numbers representing a daily ration that were cut off when entering the kitchen. If ticketed children did not show up and food remained, others without a ticket who were waiting outside received the leftovers. The ARA implemented a similar system. British Quakers based their child feeding programme on a division of the villages in their relief area into four categories. Depending on the estimated need, either 30, 20, 15, or 10 per cent of the children were fed. In contrast to both the ARA and the SCF, the British Friends’ Emergency and War Victims Relief Committee (FEWVRC) did not use their own forms to gather information about the children chosen by local committees, but relied completely on Russian authorities to do this, at least in some villages. Even Nansen, often criticised as gullible, was apparently uneasy about such an arrangement.Footnote 186

The SRC used slightly different geographical targeting methods when planning for the allocation of food in the limited area for which they were responsible. With the help of Soviet statistics, the current economic conditions in different villages were compared with their state in 1914, generally by measuring numbers of livestock. If wealth had declined by 75 per cent, three out of four inhabitants were to receive food. Accordingly, in the village of Voskresenska, where wealth had declined by 70 per cent, the proposed food entitlement comprised seven out of ten. However, Robertson’s report from the famine region suggested instead that a local moral economy prevailed, according to which the food was shared in such a way that the whole population received a 70 per cent ration.Footnote 187

Some feared that a focus on the neediest could be counterproductive or even unethical. A Mennonite relief worker pointed out that because of inadequate supply and a lack of means testing, his organisation was ‘feeding all of the thieves, vagabonds, the shiftless, the lazy poor, while the good people who had struggled and saved and put themselves on rations, had to go on eating their black bread’. He questioned whether it would not be wiser to support those who knew how to help themselves, not the least because this group ‘must ultimately take care of the poor’.Footnote 188

Gifts from government stores to SCF, the British Quakers, and Nansen ‘complicate[d] the work of distribution’, as Robertson pointed out. He referred especially to the delivery of large amounts of herring from Norway, but also cited 200 t of lime juice from British government stores that took up valuable cargo space when transported to Saratov. Robertson considered it obvious that something of this nature should be distributed in Moscow or Petrograd instead. Other deliveries, like chilled meat from Australia, had to be consumed before the frost was gone, requiring changes to be made in the standard rations.Footnote 189 The Nansen mission received a variety of food donations at different times, all of which had to be integrated in the menus. This made the development of standardised feeding plans, something most organisations tried to achieve, a difficult task.

When the SCF opened its first kitchen at the end of October 1921, local authorities were invited to test three types of soup that were to be offered in rotation. Each ration contained 720 calories and was prepared with regard to nutritional value as well as cost, transportation, and shelf-life.Footnote 190 These dishes were served in the form of a half-litre bowl of soup based on flour and either rice or beans, and served with bread. The Russian officials present made several suggestions for changes, mostly based on the assumption that Russian children would neither accept the soup nor the unfamiliar white bread. Webster rejected any changes as ‘not practical’ and claimed later a broad acceptance of the foreign meals by the children.Footnote 191