5.1 Introduction

The Anatolian branch consists of a group of languages once spoken in ancient Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and northern Syria, with textual remains dating from the beginning of the second millennium BCE to the second century CE.Footnote 1 It is commonly assumed that in the course of the first millennium CE, the entire Anatolian branch became extinct. The attested Anatolian languages are (in chronological order) as follows.Footnote 2

Kanišite Hittite:Footnote 3 a dialect of Hittite proper, which is known from hundreds of personal names and a handful of loanwords attested in Old Assyrian texts (clay tablets, written in the Old Assyrian version of the cuneiform script, dating to c. 1935–1710 BCE) mostly stemming from Kaniš/Nēša (modern-day Kültepe), Central Anatolia.

Hittite (“Ḫattuša Hittite”):Footnote 4 the main language of the administration of the Hittite kingdom, written in its own version of the cuneiform script, attested in some 30,000 fragments of clay tablets (dating to c. 1650–1180 BCE),Footnote 5 especially found in the Hittite capital Ḫattuša (modern-day Boğazkale), but also several other places in Central Anatolia. It is the best attested Anatolian language by far, and therefore the most important witness of this branch.

Palaic:Footnote 6 known from several passages embedded in Old and Middle Hittite texts (sixteenth–fifteenth century BCE), primarily dealing with the cult of the god Zaparu̯a. It was the language of the land of Palā, situated in the north-west of Central Anatolia. The Palaic corpus is small, and therefore many basic matters regarding grammar and lexicon are unclear.

Cuneiform Luwian (also called Kizzuwatna Luwian):Footnote 7 only known from cultic passages cited in Hittite texts (dating to the sixteenth–fifteenth century BCE). It was certainly spoken in Kizzuwatna (south-east of Central Anatolia) and possibly also in the western part of Anatolia. In Hittite texts from the New Hittite period (fourteenth–thirteenth century BCE), we find many Luwian loanwords, which traditionally were regarded to be Cuneiform Luwian as well but which may be more appropriately regarded as linguistically belonging to Hieroglyphic Luwian.

Hieroglyphic Luwian (also called Empire Luwian / Iron Age Luwian):Footnote 8 closely related to Cuneiform Luwian, written in an indigenous hieroglyphic script (Reference MarazziMarazzi 1998) that seems to have been especially designed for this language. Seals containing these hieroglyphs can be dated as far back as the Old Hittite period (c. 1600 BCE), but real texts (mostly inscriptions on rocks and stone steles) date from the thirteenth to the end of the eighth century BCE. The c. thirty texts that date from the last phase of the Hittite Kingdom (so-called Empire period, and therefore “Empire Luwian”) are found all over Anatolia and northern Syria, whereas the c. 230 post-Empire period inscriptions (Iron Age, and therefore “Iron Age Luwian”) are restricted to south-eastern Anatolia and northern Syria, the region of the so-called Neo-Hittite city states. Thanks to a boost in studies of the language since the publication of Reference HawkinsHawkins 2000, Hieroglyphic Luwian has become one of the better-known Anatolian languages.

Lydian:Footnote 9 the language of the land of Lydia (central western Anatolia), written in its own version of the Greek alphabet, attested in some 120 texts (the bulk of which are inscriptions on stone steles), dating from the eighth to the third century BCE (with a peak in the fifth–fourth century BCE). Our knowledge of Lydian is limited since there are only a few bilingual texts and since its vocabulary is difficult to compare to the lexicon of the other Anatolian languages (see also below, Section 5.3.3).

Carian:Footnote 10 the language of the land of Caria (south-central western Anatolia), written in its own version of the Greek alphabet, attested in some 200 inscriptions from the seventh–fifth century BCE from Egypt (tomb inscriptions from Carian mercenaries living there) and from the fourth–third century BCE from Caria itself. Our knowledge of Carian is very rudimentary: the Carian alphabet was not successfully deciphered until the 1990s, and many inscriptions contain personal names only.

Lycian (also called Lycian A):Footnote 11 the language of Lycia (south-western Anatolia), written in its own version of the Greek alphabet, in some 150 coin legends and 170 inscriptions on stone, dating to the fifth–fourth century BCE. Our knowledge of Lycian is relatively advanced, partly because of some bilingual texts (including the large trilingual inscription of Letôon) and partly because of its linguistic similarities with the Luwian languages. Nevertheless, many details regarding grammar and lexicon are still unclear.

Milyan (also called Lycian B):Footnote 12 attested in two inscriptions from Lycia (fifth century BCE) that are written in the Lycian alphabet. Although the name “Milyan” refers to the region Milyas, situated in the north-east of Lycia, it is unclear where it originates. The two Milyan inscriptions, which both seem to be in verse, are difficult to understand, and our knowledge of Milyan is therefore rudimentary.

Sidetic:Footnote 13 the language of the city of Side (south coast of Anatolia) and its surroundings, written in its own version of the Greek alphabet, attested in some ten inscriptions on coins and stone, dating to the fifth–second century BCE. The number of textual remains is very low, so we only know a few facts about Sidetic grammar and lexicon.

Pisidian:Footnote 14 a language attested in a few dozen tomb inscriptions in the Greek alphabet that were found in the eastern part of classical Pisidia (south-west of Central Anatolia), dating to the first–second century CE. The inscriptions contain only personal names, some of which point to an Anatolian character to this language.

5.2 Evidence for the Anatolian Branch

There is ample evidence to view the Anatolian languages as forming a single branch: they share enough linguistic features to set them apart as a single group vs. the rest of the Indo-European language family, cf. e.g. Reference Rieken, Klein, Joseph and FritzRieken 2017: 299. A complicating factor, however, is the Indo-Anatolian hypothesis, which states that Anatolian was the first branch to split off from the Indo-European mother language, after which the remaining language, which was to become the ancestor language of all the non-Anatolian Indo-European languages (“Core Proto-Indo-European”) underwent a set of innovations (see Section 5.5). Whenever the Anatolian languages show shared features that are different from the other Indo-European languages, we should therefore investigate to what extent these differences are caused by innovations that took place in the prehistory of the Anatolian branch, or by innovations in the prehistory of Core Proto-Indo-European. In the latter case, the Anatolian features may in fact be shared retentions, and therefore cannot, strictly speaking, be used in arguing that the Anatolian languages form a single branch. In practice, however, it is not always easy to distinguish between the two.

Another complicating factor is that some of the Anatolian languages have a very limited attestation (especially Sidetic and Pisidian) or are in general poorly understood (Carian, Milyan and, to a lesser extent, Lydian and Palaic). This means that not all features listed below are found in all languages.

The following specific features of the Anatolian languages can be regarded as examples of common innovations that prove the unity of the Anatolian branch and allow for the postulation of an ancestor language, Proto-Anatolian, from which they all derive:

Phonology

the merger of PIE mediae and aspiratae into a single series that is called lenis (PIE *d, *dʰ > PAnat. */t/),Footnote 15 which is distinct from the so-called fortis series, which is the outcome of PIE tenues (PIE *t > PAnat. */tː/)

the operation of Eichner’s lenition rules: (1) pre-PAnat. *V̄́C:V > PAnat. *V̄́CV and (2) pre-PAnat. *V́ … VC:V > PAnat. *V́… VCVFootnote 16

PIE accented short *ó was lengthened to PAnat. long */ṓ/ (and subsequently caused lenition according to Eichner’s first lenition rule)Footnote 17

the PIE cluster *h2u̯ yields PAnat. monophonemic */qʷː/,Footnote 18 e.g. PIE *trh2u̯(e)nt- > PAnat. */tːrqʷː(ə)nt-/ > Hitt. tarḫuu̯ant- /tərχʷːənt-/, CLuw. tarḫu(u̯a)nt- /tərχʷː(ə)nt‑/, Lyc. trqqãt- / trqqñt- /trkʷ(a)ⁿt-/, Car. trqδ- /trkʷⁿt-/

the development of a lateral in the word for ‘name’: PIE *h3néh3mn- > PAnat. */ʔlṓmn‑/ > Hitt. lāman, HLuw. álaman-, Lyc. alãma-

Morphology

the creation of an acc.-dat. form */ʔmːu(-)/ ‘me’ (vs. PIE *h1mmé-)

the creation of a demonstrative pronoun */ʔopṓ-/ (from virtual PIE *h1o-bʰó-)Footnote 19

the loss of the distinction between present and aorist (the “tezzi-principle”)Footnote 20

the creation of the ḫi-conjugation (cognate to the PIE perfect)Footnote 21

the 1pl. ending */-uén(i)/ (cognate to the PIE dual ending *-ué)Footnote 22

the replacement of the post-consonantal pret.act.3sg. ending *-t by the middle ending *-to (> Hitt. -tta, CLuw. -tta, HLuw. -ta, Lyc. -te)Footnote 23

the loss of the subjunctive and optative moods.

For other specifically Anatolian features, see Section 5.5, where a list of shared retentions of Anatolian will be presented (as arguments in favour of the Indo-Anatolian hypothesis).

5.3 The Internal Structure of Anatolian

There is some debate on the exact internal subgrouping of the Anatolian branch, although on some aspects there is broad consensus.

5.3.1 The Luwic Branch

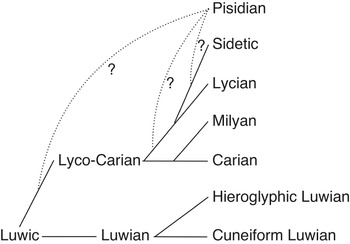

There can be no doubt that Cuneiform Luwian, Hieroglyphic Luwian and Lycian form a separate branch, which is commonly called “Luwic”. This means that these languages derive from a “Proto-Luwic” mother language. It is generally assumed that Milyan and Carian belong to this branch too, and also Sidetic and Pisidian are often regarded as possibly Luwic languages (e.g. Reference Melchert and Craig MelchertMelchert 2003: 170–7; Reference YakubovichYakubovich 2010: 6; Reference Rieken, Klein, Joseph and FritzRieken 2017: 301–3).

5.3.1.1 Shared Innovations of the Luwic Languages

The Luwic sub-branch of Anatolian can be defined through the following innovations (although they are not always attested in all languages):

Phonological

the assibilation of PAnat. */ḱː/ > PLuwic */ts/ > CLuw. z /ts/, HLuw. z /ts/, Lyc. s, Mil. s, Car. s, Sid. ś (vs. Hitt. /kː/, Pal. /kː/, Lyd. k)

the weakening of PAnat. lenis */ḱ/ > PLuwic *i̯ > Ø: e.g. PAnat. */ḱésːr-/ ‘hand’ > CLuw. ī̆š(ša)ri-, HLuw. istri-, Lyc. izri- (vs. Hitt. /k/ and Pal. /k/)

the weakening of PAnat. lenis */kʷ/ > PLuwic *u̯: e.g. PAnat. */kʷṓu-/ ‘cow’ > HLuw. wawa/i-, Lyc. wawa-, uwa- (vs. Hitt. /kʷ/, Pal. /kʷ/, Lyd. k)

the merger of PAnat. */e/ and */ō̆/ into PLuwic */ə̄̆/Footnote 24 (vs. their retention as separate phonemes in Hittite, Palaic and probably LydianFootnote 25)

Čop’s Law: PAnat. *V̆́CV > PLuwic *V̆́C:VFootnote 26

Morphological

the large-scale spread of the proterodynamic i-stem inflection replacing original consonant stem and o-stem inflection (formerly called “i-mutation”)Footnote 27

the reshaping of the PAnat. nom.pl.c. ending *-es to PLuwic *-Vns-i (based on the acc.pl.c. ending *-Vns < PIE *-V-ms + the original pronominal nom.pl.c. ending *-i < PIE *-oi?) > CLuw. -Vnzi /‑Vntsi/, HLuw. -V-zi /-Vntsi/, Lyc. -i (< *-insi), -ẽi (< *-onsi), -ãi (< *-ānsi), Car. -š (?)

the grammaticalization of the genitival adjective in *-osːo/i- > CLuw. -ašša/i-, HLuw. ‑asa/i-, Lyc. -ehe/i-, Mil. -ehe/i-, Car. -š (?), Sid. -asV, Pis. -s (?)Footnote 28

the spread of the pret.act.3sg. ending *-to to verbal stems ending in a vowel (at the cost of the original ending *-t)Footnote 29

Lexical

PLuwic *māsːVn- ‘god’ > CLuw. māššani-, HLuw. DEUS-ni-, Lyc. mahana-, Mil. masa-, Car. mso-, Sid. masara- (vs. PAnat. *tieu- (< PIE *dieu-) in Hitt. šiu-, Lyd. ciw-)Footnote 30

PAnat. *tːrqʷː(ə)nt- ‘(one who has / has been) conquered’ develops into the generic name for ‘Storm-god’ in PLuwic, yielding CLuw. tarḫu(a)nt-, HLuw. tarhunt-, Lyc. trqqñt-, Mil. trqqñt-, Car. trqδ-, all ‘Storm-god’ (vs. Hitt. tarḫuu̯ant- ‘conquered’ and dIŠKUR-unn(a)- ‘Storm-god’)Footnote 31

5.3.1.2 Internal Subgrouping of the Luwic Branch

The relationships between the three better-known Luwic languages – Cuneiform Luwian, Hieroglyphic Luwian and Lycian – are quite clear. It is generally accepted that Cuneiform Luwian and Hieroglyphic Luwian are closely related, yet distinct, dialects. The relationship between the two cannot have been a matter of one of them deriving from the other (cf. Reference Melchert and Craig MelchertMelchert 2003: 171–2), which means that both must go back to a common ancestor, which may be termed Proto-Luwian.

Lycian is generally recognized as being closely related to the two Luwian languages. Yet, although it was attested almost a millennium after the latter’s first attestations, it was clearly not a direct daughter language of either of them: the Luwian languages show innovations that are not shared by Lycian (e.g. merger of PLuwic */ə/ and */a/ into PLuwian */a/; replacement of the dat.-loc.pl. ending */-əs/ (< PAnat. */-os/) by */-əns/Footnote 32 > PLuwian */-ants/ (CLuw. -anza /-ants/, HLuw. °a-za /-ants/); fricativization of */qː/ to PLuwian */χː/ (Reference KloekhorstKloekhorst 2018a: 73–6)). This means that Lycian stems from a sister language to Proto-Luwian and that both can be regarded as distinct daughters of Proto-Luwic.

Although our knowledge of Milyan is limited, it is usually seen as being closely related to Lycian. This is based on the fact that these two languages have several linguistic features in common, which may be seen as shared innovations that set them apart from Proto-Luwian: PLuwic *-Vs > Mil., Lyc. -V (as in nom.sg.c.) (vs. PLuwian *-Vs); PLuwic *‑Vn > Mil., Lyc. -Ṽ (as in acc.sg.c.) (vs. PLuwian *-Vn); a-umlaut (e.g. Mil. nom.-acc.pl.n. uwadra vs. uwedr(i)-, or nom.-acc.pl.n. χuzruwãta vs. acc.pl.c. χuzruwẽtiz); syncope in the ethnicon suffix Mil. -wñni- and Lyc. -ñni- < *‑wnːi- (vs. PLuwian *-wanːi-); fronting of PLuwic */kʷː/ before a front vowel in rel.pron. */kʷːi‑/ > Lyc. ti-, Mil. ki- /ci-/ (vs. PLuwian *kʷi-). A shared lexical innovation may be Mil. kibe ~ Lyc. tibe ‘or’.

The position of Carian, Sidetic and Pisidian is less clear, since the number of possible isoglosses is very low. In the case of Carian, Reference AdiegoAdiego (2007: 347) states that “a meaningful isogloss shared by Carian and Milyan is the copulative conjunction Car. sb, Mil. sebe ‘and’”, which contrasts with Lyc. se ‘and’. One may add Car. mso- ~ Mil. masa- vs. Lyc. mahana- ‘god’. In the case of Sidetic, the dat.pl. ending -a (in masara ‘to the gods’), which must reflect PAnat. */-os/, shows that this language does not belong to the Luwian subgroup (which rather shows the dat.pl. ending */-ants/). Furthermore, this ending shows that Sidetic, just like Lycian and Milyan, has undergone the development *-Vs > -V, which may be seen as a shared innovation. On the basis of the Sidetic conjuction śa ‘and’, we may assume a closer affinity with Lycian, which has se ‘and’ (vs. Mil. sebe and Car. sb). In the case of Pisidian, a closer affinity with the Lyco-Carian subgroup may be seen from the nom.sg.c. ending -V, which then corresponds to Lyc. -V, Mil. -V, Car. -Ø < PLuwic *-Vs (vs. CLuw. -Vš and HLuw. -Vs). The exact position of Pisidian within this group must remain undetermined, however.

All in all, the tree of the Luwic sub-branch may be envisaged as in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 The Luwic sub-branch of Anatolian

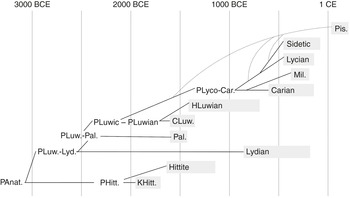

5.3.1.3 Dating Proto-Luwic

The Luwic branch seems to have been relatively shallow. As mentioned above, the linguistic difference between Cuneiform Luwian and Hieroglyphic Luwian is minimal, and we may therefore date their pre-stage, Proto-Luwian, to not much more than a handful of generations before the oldest attested Cuneiform Luwian texts (sixteenth century BCE), i.e. to c. the eighteenth century BCE. In the same vein, the difference between the Lyco-Carian branch and Proto-Luwian seems to have been relatively small, so we may assume that Proto-Luwic preceded Proto-Luwian by no more than two or three centuries. We can thus approximately date this stage to the twenty-first–twentieth century BCE.

5.3.2 The Position of Palaic

Since our knowledge of Palaic is limited, it is not easy to determine its position within the Anatolian language family with certainty. Moreover, as Reference CarrubaCarruba (1970: 4) and Reference Melchert and Craig MelchertMelchert (2003: 269) show, Palaic shares linguistic features both with Hittite and with the Luwic languages, adding to the difficulty. Nevertheless, Reference OettingerOettinger (1978) gives several arguments that would indicate that Palaic is more closely related to the Luwic languages than to Hittite and Lydian. According to Reference Rieken, Klein, Joseph and FritzRieken (2017: 303), however, “none of the isoglosses suggested so far [i.e., by Oettinger and others – AK] involve newly created morphology. In each case, the change consists of a choice among several inherited morphemes or a shift of a category’s function, mostly extending it”, and she therefore remains agnostic about the position of Palaic. To my mind, this is too negative a view: there certainly are some features that in fact can be used for judging its place in the Anatolian tree.

The Palaic dative of the 3sg. enclitic pronoun, =tu ‘to him/her’, is identical to CLuw. =tu and HLuw. =du / =ru, but distinct from Hitt. =šše (later =šši) and Lyd. =mλ. Reference OettingerOettinger (1978: 78–9) convincingly argues that this =tu originally was the dative form of the 2sg. enclitic pronoun, which was extended to the 3rd person. This non-trivial development was thus a shared innovation of Palaic and the Luwian languages.Footnote 33

In Palaic, Proto-Anatolian lenis */kʷ/ (< PIE *gʷ⁽ʰ⁾) is weakened to /xʷ/ or /χʷ/ in aḫuu̯ā̆nti ‘they drink’ < *h1gʷʰénti. This fricativization may be seen as a first step towards the full weakening that is found in Luwic, where PAnat. */kʷ/ > *u̯.Footnote 34

According to Reference StarkeStarke (1990: 71–5), Palaic shows some instances of “i-mutation”, indicating a connection with the Luwic branch. Since it has now become clear that the “i-mutation” inflection in fact goes back to a normal PIE proterodynamic i-stem inflection (cf. footnote 27), the mere existence of this type in Palaic is not remarkable per se. However, as noticed by Starke, in Palaic the “i-mutated” inflection also seems to be found in original consonant-stems (e.g. dilaliant(i)-). This implies a secondary spread that is comparable to the one found in the Luwic branch, and which may then be viewed as a shared innovation. Nevertheless, the fact that our evidence for “i-mutated” stems in Palaic is scanty shows that this spread certainly had not yet taken place on such a large scale as in the Luwic languages.

In Palaic, the pret.act.3pl. ending is -(a)nta, which matches Luwic *-Vntə (CLuw. -anta, HLuw. -anta, Lyc. -Ṽte),Footnote 35 but contrasts with Hitt. -er and Lyd. -rs / -riš. Since *-Vntə is generally regarded as deriving from the PIE 3pl. middle ending *-ento, it may be possible to see the transfer of this ending to the pret.3pl. of the active as a common innovation of Palaic and Luwic.Footnote 36

In Palaic, the only attested pret.act.1sg. ending is -(ḫ)ḫa, which reflects PAnat. */-qːa/ < PIE *-h2e, and thus originally belonged to the ḫi-conjugation. Since it is also found in the form aniēḫḫa ‘I did’ (thus Reference CarrubaCarruba 1970: 50), which was probably originally mi-conjugating, it seems that in Palaic the pret.act.1sg. ḫi-ending -(ḫ)ḫa has fully ousted the corresponding mi-ending *-m (attested in Hitt. -un, -nun and Lyd. -ν). The same development took place in Luwic, where pret.act.1sg. *-q(ː)a (CLuw. -(ḫ)ḫa, HLuw. ‑ha, Lyc. -χa, -ga) has fully ousted *-m as well. We may thus assume that Palaic and Luwic shared this innovation.Footnote 37

Although the material is scanty and the number of arguments low, it does seem safe to conclude that Palaic shares some innovations with the Luwic branch. Nevertheless, it is clear that Palaic cannot be regarded as a proper Luwic language: for instance, it does not show assibilation of PAnat. */ḱː/ (which rather yielded Pal. k; Reference MelchertMelchert 1994: 210), and it does not show a nom.pl.c. ending *-Vnsi (but rather -aš and -eš). We should therefore assume that Luwic and Palaic are related on a higher node, which may be termed Luwo-Palaic.Footnote 38

5.3.3 The Position of Lydian

The exact position of Lydian is widely debated, which is due to the fact that this language is poorly understood: only a few Lydian words can be securely translated, making it difficult to establish etymologies and thus sound correspondences with the other Anatolian languages. Nevertheless, there seems to be more and more consensus that Lydian, too, was related to the Luwic sub-branch, since the two share some isoglosses:

“i-mutation” (cf. Reference SassevilleSasseville 2017): since the “i-mutation” inflection reflects the normal PIE proterodynamic i-stem inflection (Reference NorbruisNorbruis 2021: 9–50; see also footnote 27), its presence in Lydian is not remarkable per se. However, its presence in nouns like sfardẽt(i)- ‘Sardian’ (nom.sg.c. sfardẽtiš vs. dat.pl. sfardẽtaν), which originally was probably an *-nt-stem, implies the spread of the “i-mutation” inflection at the cost of the consonant-stem inflection, which would be an innovation shared with Luwic (and Palaic).

Lydian pres.act.1sg. -u/-w is identical to PLuwic *-ū̆ (CLuw. -u̯i, HLuw. -wi, Lyc. -u),Footnote 39 which contrasts with Hitt. pres.act.1sg. -mi and -ḫḫi (unfortunately, in Palaic no pres.act.1sg. forms are attested). However, if *-ū̆ indeed goes back to the PIA thematic pres.1sg. ending *-oH (Reference Kloekhorst, Koryakov and KibrikKloekhorst 2013: 146), the ending is not the result of an innovation. Nevertheless, the fact that both in Luwic and in Lydian (as far as we can tell) *-ū̆ < *-oH ousted the athematic mi-conjugation ending *-mi and the ḫi-conjugation ending *-h2e-i (which were retained in Hittite, where a newly created *-o-mi ousted original *-oH) can be seen as a common innovation.Footnote 40

Lydian -cuwe- ‘to erect(?)’ is regarded by Reference OettingerOettinger (1978: 89) and Reference Melchert and Craig MelchertMelchert (2003: 269) as cognate to CLuw. tūu̯a- ‘to place’, HLuw. tuwa-i ‘to place’ and Lyc. tuwe- ‘to place (upright)’, which all reflect a stem *tuu̯V-. Although there are different views on the exact origin of this formation, it is mostly seen as an innovation, which then must have been shared by Lydian and the Luwic languages.Footnote 41

Note that we are not necessarily dealing with a shared innovation in all cases in which Lydian coincides with Luwic:

Lyd. taada- ‘father’ < *tóto- is cognate with PLuwic. *tóti- (CLuw. tāti-, HLuw. tati-, Lyc. tedi-, Car. ted), which differs from Hitt. atta- and Pal. pāpa- ‘father’. However, since it cannot be excluded that *tóto- is the Proto-Anatolian form, whereas Hitt. atta- and Pal. pāpa- are innovations, this isogloss between Lydian and Luwic (see below for the difference in “i-mutation”) could in principle represent a shared retention and is therefore non-probative.

Lydian has a 1sg. reflexive particle =m, which is identical to PLuwic *=mi (CLuw. =mi(?), HLuw. =mi), but contrasts with Hittite, which uses =z(a) < *=ti in this function (no attestations known for Palaic). Since it cannot be excluded that Lydian and Luwic reflect the Proto-Anatolian situation, whereas Hittite may have undergone an innovation, this isogloss may represent a shared retention and therefore is non-probative.

Moreover, there are also some Luwic isoglosses in which Lydian clearly does not participate:

PAnat. lenis /kʷ/ > Lyd. k in kãna- ‘woman’ < *gʷoneh2- (whereas in PLuwic, PAnat. */kʷ/ is weakened to *u̯, e.g. *gʷoneh2- > CLuw. u̯āna-)

Lyd. ciw- ‘god’ < PAnat. */tieu-/ < PIE *dieu- (vs. PLuwic *māsːVn- ‘god’)

Lyd. a-stem noun taada- ‘father’ (vs. PLuwic “i-mutated” *tóti-, see the forms cited above)

I am therefore reluctant to view Lydian as a proper Luwic language; rather, I assume that both Lydian and Proto-Luwic derive from an earlier node. In order to establish the position of this node vis-à-vis the Luwo-Palaic node as assumed above, the following arguments can be used:

The Lydian dat.sg. form of the 3rd person enclitic pronoun, =mλ ‘to him/her’, can be derived from *=smei̯ / *=smoi̯ (Reference KloekhorstKloekhorst 2012: 169), which to my mind is an archaic morpheme (cognate with the PIE element *-sm- as found in, e.g., the Skt. pronominal stem tasm-). Lydian thus did not participate in the Luwo-Palaic innovation by which the original dat.sg. of the 2nd person enclitic pronoun, *=tu, was extended to the 3rd person.Footnote 42

The Lydian pret.act.1sg. ending is -ν, which reflects the PAnat. mi-conjugation ending *-m. Since in Lydian no trace of the corresponding PAnat. ḫi-conjugation ending *‑q(ː)a (< PIE *-h2e) is found, we may assume that *-m > Lyd. -ν had been generalized at the cost of *-q(ː)a. This would then be a reverse development to the generalization of the ḫi-conjugation ending *-q(ː)a at the cost of *-m that took place in Palaic and Luwic, and which was mentioned above as a possible shared innovation between these latter two branches.

It is for these reasons that I assume that the “Luwo-Lydian” node must be placed higher up the family tree than Luwo-Palaic (thus also Reference OettingerOettinger 1978: 92; Reference YakubovichYakubovich 2010: 6).

5.3.4 The Position of Hittite

Hittite proper (“Ḫattuša Hittite”) knew a sister dialect, Kanišite Hittite, that is very similar to it but in some points does deviate (Reference KloekhorstKloekhorst 2019). This calls for the postulation of a Proto-Hittite ancestor language that may have been spoken only a few generations before the oldest attestations of Kanišite Hittite (twentieth century BCE), i.e. around 2100 BCE.

As has become clear in the sections above, there are no clear linguistic innovations that Hittite shares with any of the other Anatolian languages.Footnote 43 As Rieken puts it, Hittite is “notorious for [its] conservatism” (Reference Rieken, Klein, Joseph and Fritz2017: 303). However, this does not mean that Hittite can be directly equated with Proto-Anatolian: Hittite, too, has undergone its specific innovations (e.g. the assibilation of dental stop + *i̯; the almost complete elimination of paradigmatic alternations between fortis and lenis stops; the reshaping of some verbal endings; the transfer of many mi-verbs to the ḫi-conjugation (Reference NorbruisNorbruis 2021: 131–207); the spread of the n-suffix in the word for ‘earth’; etc.).

5.3.5 Dating Proto-Anatolian

Although it is difficult to say anything certain about the absolute dating of reconstructed ancestor languages, in the case of Proto-Anatolian we have seen that its two best-known branches, Luwic and Hittite, have proto-languages that are roughly contemporaneous: Proto-Luwic can be approximately dated to the twenty-first–twentieth century BCE, and Proto-Hittite to c. 2100 BCE. The difference between the two is quite sizable, and elsewhere (Reference Kloekhorst, Kristiansen and KroonenKloekhorst in press) I have therefore argued that they may have been a millennium apart from each other, which would mean that Proto-Anatolian started to diverge sometime around the thirty-first century BCE.

5.3.6 The Dialectal Make-Up of Anatolian

Taking all these points into account, we arrive at a tree model of the Anatolian branch as shown in Figure 5.2.Footnote 44

Figure 5.2 Tree model of the Anatolian languages

5.4 The Relationship of Anatolian to the Other Branches

In Reference Puhvel and Dunkel1994, Puhvel argued that Anatolian shares many linguistic features with Celtic, Germanic, Italic, Tocharian and, to a lesser extent, Greek, which would point to a genetic relationship between Anatolian and these “western” branches. For instance, Hitt. išpant‑i ‘to libate’ matches Lat. spondeō and Gr. σπένδω but has no cognates anywhere else. However, as Reference Melchert and BjarneMelchert (2016: 300) rightly states, all such cases “can be interpreted as common retentions that just happen to be preserved in Anatolian and the western dialects” and therefore “simply are not probative” for determining the position of Anatolian in the Indo-European family tree: only secured common innovations can be used to this end. Melchert himself thinks that such common innovations between Anatolian and “western” languages may indeed exist, but, to his mind, they would rather prove “post-divergence contact between Anatolian and the western dialects” (Reference Melchert and Bjarne2016: 300), and thus have no bearing on the genealogical position of Anatolian. Although space limitations do not allow me to examine the four examples treated by Reference Melchert and BjarneMelchert (2016), it is quite clear that none of them can withstand scrutiny. There is thus no reason to assume that Anatolian shares any innovations, either contact-induced or caused by a genetic relationship, with “western” Indo-European languages or, for that matter, with any of the other Indo-European languages.

5.5 The Position of Anatolian

A hotly debated issue with regard to Anatolian is the so-called Indo-Anatolian hypothesis (also “Indo-Hittite hypothesis”), which states that Anatolian was the first branch to split off from the Indo-European mother language (which then may be called “Proto-Indo-Anatolian” or “Proto-Indo-Hittite”), after which the remaining language, which was to become the mother language of all the non-Anatolian Indo-European languages (and which may be called “Core Proto-Indo-European”, “Nuclear Proto-Indo-European”, “Classical Proto-Indo-European” or similar) underwent a set of innovations. There is some debate on whether this hypothesis is valid at all, and if so, how large the gap is between the moment Anatolian split off and the time that the first split within Core Proto-Indo-European (CPIE) took place (which is usually thought to have been the split-off of Tocharian, see Chapter 6). Some scholars do not think that there is enough evidence for assuming an early split-off of Anatolian at all (Reference RiekenRieken 2009; Reference AdiegoAdiego 2016); others think that there may have been an early split, but that the gap between Anatolian and the next split is relatively modest (Reference Eichner, Krisch and NiederreiterEichner 2015; Reference Melchert, Weiss and GarrettMelchert in press), whereas still others think that the gap is sufficiently large for the Proto-Indo-Anatolian ancestor language to be substantially different from Core Proto-Indo-European (Reference KloekhorstKloekhorst 2008: 7–11; Reference OettingerOettinger 2014; Reference Kloekhorst, Pronk, Kloekhorst and PronkKloekhorst & Pronk 2019).

The validity of the Indo-Anatolian hypothesis can only be proven if enough secured shared innovations of the non-Anatolian languages can be found. In Reference Kloekhorst, Pronk, Kloekhorst and PronkKloekhorst & Pronk 2019: 3–6, a total of thirty-four linguistic features are listed in which Anatolian deviates from the other Indo-European languages, and which are presented as possible cases in which Anatolian has retained the original state of affairs, whereas the other Indo-European languages have undergone a common innovation (with twenty-three examples classified as “good candidates”, and eleven as “less forceful” but “promising” ones). These include:

Semantic Innovations

The Hittite participle suffix -ant- forms both active and passive participles, whereas in CPIE the suffix *-e/ont- only forms active participles: narrowing of the function of *-e/ont- in CPIE (Reference OettingerOettinger 2014: 156–7).

The Hitt. active verb ēš-zi < *h1es-ti means ‘to sit’ next to its middle counterpart eš-a(ri) < *h1e-h1s-°, which means ‘to sit down’, whereas in CPIE the middle verb *h1e-h1s-to means ‘to sit’ next to the verbal root *sed- ‘to sit down’: expansion of the meaning of *h1e-h1s- from ‘to sit down’ to ‘to sit’, with replacement of *h1e-h1s- ‘to sit down’ by *sed- (Reference NorbruisNorbruis 2021: 235–41).

Hitt. ḫarra-i < *h2erh3- means ‘to grind, crush’, whereas CPIE *h2erh3- means ‘to plough’: semantic specialisation in CPIE (Reference KloekhorstKloekhorst 2008: 9).

Hitt. mer- < *mer- means ‘to disappear’, whereas CPIE *mer- means ‘to die’: semantic shift, through euphemism, in CPIE (Reference KloekhorstKloekhorst 2008: 8).

Morphological Innovations

Anatolian has two genders (common/neuter), whereas CPIE has three genders (m./f./n.): creation of the feminine gender in CPIE (e.g. Reference Melchert, Weiss and GarrettMelchert in press).

Anatolian has nom. *ti(H), obl. *tu- ‘ you (sg.)’, whereas CPIE has nom. *tuH, obl. *tu-: spread of obl. stem *tu- to the nominative in CPIE (Reference KloekhorstKloekhorst 2008: 8–9).

Anat. *h1eḱu- vs. CPIE *h1eḱu-o- ‘horse’: thematization in CPIE (Reference KloekhorstKloekhorst 2008: 10).

Hitt. ḫuu̯ant- < *h2uh1-ent- vs. CPIE *h2ueh1nt-o- ‘wind’: thematization in CPIE (Reference Eichner, Krisch and NiederreiterEichner 2015: 17–18).

Sound Changes

Anat. *h2 = *[qː] and *h3 = *[qːʷ] vs. CPIE *h2 = *[ħ] or *[ʕ] and *h3 = *[ħʷ] or *[ʕʷ]: fricativization of uvular stops in CPIE (Reference KloekhorstKloekhorst 2018a).

Hitt. amm- < *h1mm- (< pre-PIE *h1mn-) vs. CPIE *h1m- ‘me’: degemination of *mm to *m in CPIE (Reference KloekhorstKloekhorst 2008: 111 n. 234).

Although it is certainly possible that not all of the arguments listed in Reference Kloekhorst, Pronk, Kloekhorst and PronkKloekhorst & Pronk 2019 will eventually become generally accepted, it seems very unlikely that they will all be refuted, and the Indo-Anatolian hypothesis can thus be regarded as virtually proven. Moreover, since the number of arguments listed is relatively large and some of them concern significant structural innovations (especially the rise of the feminine gender in CPIE, including the creation of the accompanying morphology), it has been argued that the temporal gap between the Anatolian split and the subsequent Tocharian split (cf. Chapter 6) may have been in the range of 800–1000 years. With the Tocharian split commencing around 3400–3300 BCE, the Anatolian split may be dated to the period between 4400–4100 BCE. If Proto-Anatolian indeed first broke up into its daughter languages around the thirty-first century BCE (see Section 5.3.5), it would mean that it had some 1,300–1000 years to undergo the specific innovations that define Anatolian as a separate branch (see Section 5.2). Since these innovations include some large restructurings of especially the verbal system (loss of the subjunctive and optative mood, merger of the present and aorist aspects, creation of the ḫi-conjugation on the basis of the PIE perfect), such a time span would certainly be fitting.