Summary Contents

The owner of an intellectual property (IP) right, whether a patent, copyright, trademark, trade secret or other right, has the exclusive right to exploit that right. Ownership of an IP right is thus the most effective and potent means for utilizing that right. But what does it mean to “own” an IP right and how does a person – an individual or a firm – acquire ownership of it? This chapter explores transfers and assignments of IP ownership, first in general, and then with respect to special considerations pertinent to patents, copyrights and trademarks. Assignments and transfers of IP licenses, another important topic, are covered in Section 13.3, and attempts to prohibit an assignor of IP from later challenging the validity of transferred IP (through a contractual no-challenge clause or the common law doctrine of “assignor estoppel”) are covered in Chapter 22.

2.1 Assignments of Intellectual Property, Generally

Once it is in existence, an item of IP may be bought, sold, transferred and assigned much as any other form of property. Like real and personal property, IP can be conveyed through contract, bankruptcy sale, will or intestate succession, and can change hands through any number of corporate transactions such as mergers, asset sales, spinoffs and stock sales.

The following case illustrates how IP rights will be treated by the courts much as any other assets transferred among parties. In this case, the court must interpret a “bill of sale,” the document listing assets conveyed in a particular transaction. Just as with bushels of grain or tons of steel, particular IP rights can be listed in a bill of sale and the manner in which they are listed will determine what the buyer receives.

228 Fed. Appx. 854 (11th Cir. 2007) (cert. denied)

Per Curiam

Following the settlement of a dispute between Systems Unlimited, Inc. and Cisco Systems, Inc. over the ownership of certain intellectual property, Cisco agreed to covey the property to Systems. In the resulting bill of sale, Cisco:

granted, bargained, sold, transferred and delivered, and by these presents does grant, bargain, sell, transfer and deliver unto [Systems], its successor and assigns, the following:

Any and all of [Cisco]’s right, title and interest in any copyrights, patents, trademarks, trade secrets and other intellectual property of any kind associated with any software, code or data, including without limitation host controller software and billing software, whether embedded or in any other form (including without limitations, disks, CDs and magnetic tapes), and including any and all available copies thereof and any and all books and records related thereto by [Cisco]

Cisco never delivered [copies of] any of the software to Systems. Alleging that it had been damaged by the non-delivery, Systems sued Cisco for breaching the bill of sale contract and for violating the attendant obligations to deliver the software under the Uniform Commercial Code.

Systems contends that the district court erred in granting summary judgment in favor of Cisco because: (1) the plain language of the bill of sale required Cisco to deliver the software; (2) the bill of sale, when read in conjunction with other contemporaneous agreements, required delivery; and (3) the UCC, which governs the bill of sale, requires that all goods be delivered at a reasonable time. Systems is wrong on each point.

The bill of sale is interpreted in accord with its plain language absent some ambiguity. Here, the parties agree that the bill of sale is clear and unambiguous.

The bill of sale provides that Cisco will “grant, bargain, sell, transfer and deliver unto [Systems] … [a]ny and all of [Cisco]’s right, title and interest in any copyrights, patents, trademarks, trade secrets and other intellectual property of a kind associated with any software, code or data.” As the district court explained, this language unambiguously means that Cisco was required by the bill of sale to transfer to Systems all of its rights in intellectual property associated with certain software and data. There is no mention in the plain language of the contract itself of Cisco being obligated to transfer the actual software, and we will not imply any such obligation absent some good reason under law.

Systems says there are two good reasons to imply an obligation by Cisco to transfer the software. First, Systems argues that the bill of sale must be interpreted in conjunction with the settlement agreement between Systems and Cisco and other documents relating to the intellectual property. These other agreements, Systems claims, include an obligation by Cisco to deliver the software with any conveyance of intellectual property.

Assuming without deciding that the other agreements include language requiring Cisco to deliver the software, they are not relevant here because Systems has never alleged Cisco violated these other agreements. Systems’ complaint alleges only a violation of the bill of sale contract, and there is no obligation in that contract to deliver the software. The bill of sale does not reference or incorporate any other agreement.

To get around this point, Systems argues that “when instruments relate to the same matters, are between the same parties, and made part of substantially one transaction, they are to be taken together.” It is true that this is one of the canons for construing a contract under California law. But it is also true that this canon, as with most others, is inapplicable where the contract that is alleged to have been breached is unambiguous. Here, the language of the bill of sale is unambiguous. Thus, there is no need to apply any canons of construction.

Systems also argues that the UCC imposes a duty on Cisco to deliver the software. We will assume without deciding that Systems’ reading of the UCC is correct. Even so, the provisions of the UCC only apply to contracts that deal predominately with “transactions in goods.” The sale of intellectual property, which is what is involved here, is not a transaction in goods. Thus, the UCC does not apply. Accordingly, the plain language of the bill of sale governs and, as the district court held, it does not include a provision requiring Cisco to deliver any software.

AFFIRMED.

Notes and Questions

1. IP and the UCC. The court in Systems v. Cisco holds that IP licenses and other transactions are not governed by Article 2 of the UCC, which pertains to sales of goods. In Section 3.4 we will discuss whether and to what degree Article 2 applies to IP licenses. But this case relates not to a license, but to a “sale” of software. Why doesn’t UCC Article 2 apply? Should it?

2. Delivery of what? What does this language from the bill of sale refer to, if not delivery of software: “including any and all available copies thereof”? Does this language represent a drafting mistake by Systems’ attorney? Or an intentional omission by Cisco?

3. The need for software. Why is Systems so upset that Cisco has allegedly refused to deliver the software in question? How useful is an assignment of copyright and other IP to someone who is not in possession of the software code that is copyrighted? Has Cisco “pulled a fast one” on Systems and the court, or is there a valid business reason that could justify Cisco’s failure to deliver the software?

4. Statute of frauds. Assignments of copyrights, patents and trademarks must all be in writing (17 U.S.C. § 204(a), 35 U.S.C. § 261, 15 U.S.C. § 1060(3)). Why? This requirement does not apply to most licenses, which may be oral. Can you think of a good reason for this distinction?

5. State law and mutual mistake. Despite the federal statutory nature of patents, courts have long held that the question of who holds title to a patent is a matter of state contract law.Footnote 1 This issue arose in an interesting way in Schwendimann v. Arkwright Advanced Coating, Inc., 959 F.3d 1065 (Fed. Cir. 2020). In Schwendimann, the plaintiff’s former company purported to assign her a patent application in 2003. Due to a clerical error by the law firm handling the matter, the assignment document filed with the patent office listed the wrong patent name and number. In 2011, the plaintiff filed an action asserting the patent against an alleged infringer. The defendant, discovering the incorrect assignment document from 2003, moved to dismiss on the ground that the plaintiff did not hold any enforceable rights at the time she filed suit and thus lacked standing. The district court, interpreting applicable state law, held that the 2003 assignment was the result of a “mutual mistake of fact” that did not accurately reflect the intent of the parties. Accordingly, the erroneous document could be reformed and was sufficient to support standing to bring suit. The Federal Circuit affirmed. Judge Reyna dissented, reasoning that, irrespective of the district court’s later reformation of the erroneous assignment, the plaintiff’s failure to own the patent at the time her suit was filed necessarily barred her suit under Article III of the Constitution. Which of these positions do you find more persuasive? Notwithstanding the holding in favor of the plaintiff, is there a claim for legal malpractice against the law firm in question?

2.2 Assignment of Copyrights and the Work Made for Hire Doctrine

Under § 201(a) of the Copyright Act, copyright ownership “vests initially in the author or authors of the work.” A copyright owner may assign any of its exclusive rights, in full or in part, to a third party. The assignment generally must be in writing and signed by the owner of the copyright or his or her authorized agent (17 U.S.C. § 204(a)).

If a work of authorship is prepared by an employee within the scope of his or her employment, then the work is a “work made for hire” and the employer is considered the author and owner of the copyright (17 U.S.C. § 201(b)). In addition, if a work is not made by an employee but is “specially ordered or commissioned,” it will be considered a work made for hire if it falls into one of nine categories enumerated in § 101(2) of the Act: a contribution to a collective work, a part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, a translation, a supplementary work, a compilation, an instructional text, a test, answer material for a test, or an atlas. Commissioned works that do not fall into one of these nine categories (for example, software) are not automatically considered to be works made for hire, and copyright must be assigned explicitly through a separate assignment or sale agreement.

Warren v. Fox Family Worldwide, Inc.

328 F.3d 1136 (9th Cir. 2003)

HAWKINS, Circuit Judge.

In this dispute between plaintiff-appellant Richard Warren (”Warren”) and defendants-appellees Fox Family Worldwide (“Fox”), MTM Productions (“MTM”), Princess Cruise Lines (“Princess”), and the Christian Broadcasting Network (“CBN”), Warren claims that defendants infringed the copyrights in musical compositions he created for use in the television series “Remington Steele.” Concluding that Warren has no standing to sue for infringement because he is neither the legal nor beneficial owner of the copyrights in question, we affirm the district court’s Rule 12 dismissal of Warren’s complaint.

Warren and Triplet Music Enterprises, Inc. (“Triplet”) entered into the first of a series of detailed written contracts with MTM concerning the composition of music for “Remington Steele.” This agreement stated that Warren, as sole shareholder and employee of Triplet, would provide services by creating music in return for compensation from MTM. Under the agreement, MTM was to make a written accounting of all sales of broadcast rights to the series and was required to pay Warren a percentage of all sales of broadcast rights to the series made to third parties not affiliated with ASCAP or BMI. These agreements were renewed and re-executed with slight modifications in 1984, 1985 and 1986.

Warren brought suit in propria persona against Fox, MTM, CBN, and Princess, alleging copyright infringement, breach of contract, accounting, conversion, breach of fiduciary duty, breach of covenants of good faith and fair dealing, and fraud.

Warren claims he created approximately 1,914 musical works used in the series pursuant to the agreements with MTM; that MTM and Fox have materially breached their obligations under the contracts by failing to account for or pay the full amount of royalties due Warren from sales to parties not affiliated with ASCAP or BMI; and that MTM and Fox infringed Warren’s copyrights in the music by continuing to broadcast and license the series after materially breaching the contracts. As to the other defendants, Warren claims that CBN and Princess infringed his copyrights by broadcasting “Remington Steele” without his authorization. Warren seeks damages, an injunction, and an order declaring him the owner of the copyrights at issue.

Defendants argu[ed] that Warren’s infringement claims should be dismissed for lack of standing because he is neither the legal nor beneficial owner of the copyrights. The district court dismissed Warren’s copyright claims without leave to amend and dismissed his state law claims without prejudice to their refiling in state court, holding that Warren lacked standing because the works were made for hire, and because a creator of works for hire cannot be a beneficial owner of a copyright in the work. Warren appeals.

The first agreement [between the parties], signed on February 25, 1982, states that MTM contracted to employ Warren “to render services to [MTM] for the television pilot photoplay now entitled ‘Remington Steele.’” It also is clear that the parties agreed that MTM would “own all right, title and interest in and to [Warren’s] services and the results and proceeds thereof, and all other rights granted to [MTM] in [the Music Employment Agreement] to the same extent as if … [MTM were] the employer of [Warren].” The Music Employment Agreement provided:

As [Warren’s] employer for hire, [MTM] shall own in perpetuity, throughout the universe, solely and exclusively, all rights of every kind and character, in the musical material and all other results and proceeds of the services rendered by [Warren] hereunder and [MTM] shall be deemed the author thereof for all purposes.

Figure 2.1 Warren claimed that he created 1,914 musical works for the popular 1980s TV series Remington Steele.

The parties later executed contracts almost identical to these first agreements in June 1984, July 1985, and November 1986. As the district court noted, these subsequent contracts are even more explicit in defining the compositions as “works for hire.” Letters that Warren signed accompanying the later Music Employment Agreements provided: “It is understood and agreed that you are supplying [your] services to us as our employee for hire … [and] [w]e shall own all right, title and interest in and to [your] services and the results and proceeds thereof, as works made for hire.”

That the agreements did not use the talismanic words “specially ordered or commissioned” matters not, for there is no requirement, either in the Act or the caselaw, that work-for-hire contracts include any specific wording. In fact, in Playboy Enterprises v. Dumas, 53 F.3d 549 (2d Cir. 1995), the Second Circuit held that legends stamped on checks were writings sufficient to evidence a work-for-hire relationship where the legend read: “By endorsement, payee: acknowledges payment in full for services rendered on a work-made-for-hire basis in connection with the Work named on the face of this check, and confirms ownership by Playboy Enterprises, Inc. of all right, title and interest (except physical possession), including all rights of copyright, in and to the Work.” Id. at 560. The agreements at issue in the instant case are more explicit than the brief statement that was before the Second Circuit.

In this case, not only did the contracts internally designate the compositions as “works made for hire,” they provided that MTM “shall be deemed the author thereof for all purposes.” This is consistent with a work-for-hire relationship under the Act, which provides that “the employer or other person for whom the work was prepared is considered the author.” 17 U.S.C. § 201(b).

Warren argues that the use of royalties as a form of compensation demonstrates that this was not a work-for-hire arrangement. While we have not addressed this specific question, the Second Circuit held in Playboy that “where the creator of a work receives royalties as payment, that method of payment generally weighs against finding a work-for-hire relationship.” 53 F.3d at 555. However, Playboy clearly held that this factor was not conclusive. In addition to noting that the presence of royalties only “generally” weighs against a work-for-hire relationship, Playboy cites Picture Music, Inc. v. Bourne, Inc., 457 F.2d 1213, 1216 (2d Cir. 1972), for the proposition that “[t]he absence of a fixed salary … is never conclusive.” 53 F.3d at 555. Further, the payment of royalties was only one form of compensation given to Warren under the contracts. Warren was also given a fixed sum “payable upon completion.” That some royalties were agreed upon in addition to this sum is not sufficient to overcome the great weight of the contractual evidence indicating a work-for-hire relationship.

Warren also argues that because he created nearly 2,000 musical works for MTM, the works were not specially ordered or commissioned. However, the number of works at issue has no bearing on the existence of a work-for-hire relationship. As the district court noted, a weekly television show would naturally require “substantial quantities of verbal, visual and musical content.”

The agreements between Warren and MTM conclusively show that the musical compositions created by Warren were created as works for hire, and Warren is therefore not the legal owner of the copyrights therein.

AFFIRMED.

Notes and Questions

1. Employee v. Contractor. In Warren v. Fox the musical compositions created by Warren fell into one of the nine categories of “specially commissioned works” that qualify as works made for hire under § 101(2) of the Copyright Act (audiovisual works), even if they were not made by employees of the commissioning party. They will thus be classified as works made for hire so long as they can be shown to have been “specially commissioned” – the focus of the debate in Warren. A slightly different question arose in Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid, 490 U.S. 730 (1989). In that case Reid, a sculptor, was engaged by a nonprofit organization, CCNV, to create a memorial “to dramatize the plight of the homeless.” Sculpture is not one of the nine enumerated categories of commissioned works. Thus, even if Reid’s sculpture were “specially commissioned” (as it probably was), it would not be classified as a work made for hire under § 101 unless Reid were considered to be an employee of CCNV. CCNV argued that it exercised a certain degree of control over the subject matter of the sculpture, making it appropriate to classify Reid as its employee. The Court disagreed:

Reid is a sculptor, a skilled occupation. Reid supplied his own tools. He worked in his own studio in Baltimore, making daily supervision of his activities from Washington practicably impossible. Reid was retained for less than two months, a relatively short period of time. During and after this time, CCNV had no right to assign additional projects to Reid. Apart from the deadline for completing the sculpture, Reid had absolute freedom to decide when and how long to work. CCNV paid Reid $15,000, a sum dependent on completion of a specific job, a method by which independent contractors are often compensated. Reid had total discretion in hiring and paying assistants. Creating sculptures was hardly regular business for CCNV. Indeed, CCNV is not a business at all. Finally, CCNV did not pay payroll or Social Security taxes, provide any employee benefits, or contribute to unemployment insurance or workers’ compensation funds.

Does the structure of the works made for hire doctrine under § 101(2) of the Copyright Act make sense? Why should specially commissioned works be considered works for hire only if they fall into one of the nine enumerated categories? Why is a musical composition treated so differently than a sculpture?

2. Manner of compensation. The form of compensation received by the author is mentioned in both Warren v. Fox and CCNV v. Reid. Why is this detail significant to the question of works made for hire? Are the courts’ conclusions with respect to compensation consistent between these two cases?

3. Software contractors and assignment. For a variety of professional, financial and tax-planning reasons, software developers often work as independent contractors and are not hired as employees of the companies for which they create software. And, like the sculpture in CCNV v. Reid, software is not one of the nine enumerated categories of works under § 101(2) of the Copyright Act. Thus, even if it is specially commissioned, software will not be considered a work made for hire. As a result, companies that use independent contractors to develop software must be careful to put in place copyright assignment agreements with those contractors. And because contractors often sit and work beside company employees with very little to distinguish them, neglecting to take these contractual precautions is one of the most common IP missteps made by fledgling and mature software companies alike. If you were the general counsel of a new software company, how would you deal with this issue?

4. Recordation. Section 205 of the Copyright Act provides for recordation of copyright transfers with the Copyright Office. Recordation of transfers is not required, but provides priority if the owner attempts to transfer the same copyrighted work multiple times:

§ 205(d) Priority between Conflicting Transfers.—As between two conflicting transfers, the one executed first prevails if it is recorded, in the manner required to give constructive notice … Otherwise the later transfer prevails if recorded first in such manner, and if taken in good faith, for valuable consideration or on the basis of a binding promise to pay royalties, and without notice of the earlier transfer.

As students of real property will surely observe, this provision resembles a “race-notice” recording statute under state law. As such, the second transferee of a copyright may prevail over a prior, unrecorded transferee if the second transferee records first without notice of the earlier transfer. Note also that this provision is applicable only to copyrights that are registered with the Copyright Office.

5. Statutory termination of assignments. Sections 203 and 304 of the Copyright Act provide that any transfer of a copyright can be revoked by the transferor between 35 and 40 years after the original transfer was made.Footnote 2 This remarkable and powerful right is irrevocable and cannot be contractually waived or circumvented. It was intended to enable authors who were young and unrecognized when they first granted rights to more powerful publishers to profit from the later success of their works. For example, in 1938 Jerry Siegel and Joseph Shuster, the creators of the Superman character, sold their rights to the predecessor of DC Comics for $130. Siegel and Shuster both died penniless in the 1990s, while Superman earned billions for his corporate owners.

Though Sections 203 and 304 were originally directed to artists, writers and composers, these provisions apply across the board to all copyrighted works including software and technical standards documents. The possibility that an original developer of Microsoft Windows could suddenly pull the plug on millions of existing licenses is somewhat ameliorated because the reversion does not apply to works made for hire or derivative works. Nevertheless, one must ask why these reversionary rights apply to software and technical documents at all. If such works of authorship are excluded as works made for hire under Section 101(2), why shouldn’t they also be excluded from Sections 203/304?Footnote 3 Is there any justification for allowing developers of copyrighted “technology” products to terminate assignments made decades ago?

6. Divisibility of copyright. Prior to the Copyright Act of 1976, copyright ownership was not divisible. That is, the owner of a copyright, say in a book, could not assign the exclusive right to produce a film based on that book to a third party. The right to produce a film could be licensed to a third party, but an attempted assignment of the right would potentially be invalid or treated as a license.Footnote 4 But today, under 17 U.S.C. § 201(d)(2), “Any of the exclusive rights comprised in a copyright, including any subdivision of any of the rights specified by section 106, may be transferred … and owned separately.” What do you think was the rationale for this change in the law? Why would, say, a film studio prefer to “own” the right to produce a film based on a book rather than have a license to do so?

Figure 2.2 The creators of the Superman character died in near poverty while the Man of Steel went on to form a multi-billion-dollar franchise. Sections 203 and 304 of the US Copyright Act were enacted to enable authors and their heirs to terminate any copyright assignment or license between 35 and 40 years after originally made in order to permit them to share in the value of their creations.

2.3 Assignment Of Patent Rights

As with other IP rights, patents, patent applications and inventions may be assigned. Patent rights initially vest in inventors who are, by definition, individuals. Unlike copyright, there is no work made for hire doctrine under US patent law. However, if an employee is “hired to invent” – that is, to perform tasks intended to result in an invention – then the employee may have a legal duty to assign the resulting invention to his or her employer.Footnote 5

Unfortunately, the “hired to invent” doctrine is murky and inconsistently applied.Footnote 6 Thus, most employers today contractually obligate their employees to assign rights in inventions and patents to them when made within the scope of their employment and/or using the employer’s resources or facilities. This requirement exists in the private sector, at nonprofit universities and research institutions, as well as government agencies. The initial assignment from an inventor to his or her employer is often filed during prosecution of a patent on a form provided by the Patent and Trademark Office. If such an assignment is not filed, the inventor’s employer obtains no rights in an issued patent other than so-called “shop rights” that allow the employer to use the patented invention on a limited basis.Footnote 7

Beyond the initial assignment from the inventor(s), the owner of a patent may assign it to a third party as any other property right. The following case turns on whether an inventor assigned his rights to his employer at the time the invention was conceived, or when the patent was issued.

Filmtec Corporation v. Allied-Signal Inc.

939 F.2d 1568 (Fed. Cir. 1991)

PLAGER, CIRCUIT JUDGE

Allied-Signal Inc. and UOP Inc. (Allied), defendants-appellants, appeal from the preliminary injunction issued by the district court. The trial court enjoined Allied from “making, using or selling, and actively inducing others to make use or sell TFCL membrane in the United States, and from otherwise infringing claim 7 of United States Patent No. 4,277,344 [’344].” Because of serious doubts on the record before us as to who has title to the invention and the ensuing patent, we vacate the grant of the injunction and remand for further proceedings.

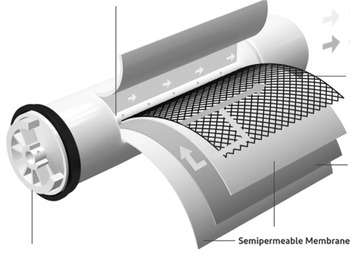

The application which ultimately issued as the ‘344 patent was filed by John E. Cadotte on February 22, 1979. The patent claims a reverse osmosis membrane and a method for using the membrane to reduce the concentration of solute molecules and ions in solution. Cadotte assigned his rights in the application and any subsequently issuing patent to plaintiff-appellee FilmTec. This assignment was duly recorded in the United States Patent and Trademark Office. Defendant-appellant Allied manufactured a reverse osmosis membrane and FilmTec sued Allied for infringing certain claims of the ’344 patent.

John Cadotte was one of the four founders of FilmTec. Prior to founding FilmTec, Cadotte and the other founders were employed in various responsible positions at the North Star Division of Midwest Research Institute (MRI), a not-for-profit research organization. MRI was principally engaged in contract research, much of it for the United States (Government), and much of it involving work in the field of reverse osmosis membranes.

The evidence indicates that the work at MRI in which Cadotte and the other founders were engaged was being carried out under contract (the contract) to the Government. The contract provided that MRI

agrees to grant and does hereby grant to the Government the full and entire domestic right, title and interest in [any invention, discovery, improvement or development (whether or not patentable) made in the course of or under this contract or any subcontract … thereunder].

It appears that sometime between the time FilmTec came into being in 1977 and the time Cadotte submitted his patent application in February of 1979, he made the invention that led to the ’344 patent. As we will explain, just when in that period the invention was made is critical.

Cadotte left MRI in January of 1978. Cadotte testified that he conceived his invention the month after he left MRI. Allied disputes this, and alleges that Cadotte conceived his invention and formed the reverse osmosis membrane of the ’344 patent earlier—in July of 1977 or at least by November of 1977 when he allegedly produced an improved membrane.

Allied alleges that the evidence establishes that the contract between MRI and the Government grants to the Government “all discoveries and inventions made within the scope of their [i.e., MRI’s employees] employment,” and that the invention claimed in the ’344 patent was made by Cadotte while employed by MRI. From this Allied reasons that rights in the invention must be with the Government and therefore Cadotte had no rights to assign to FilmTec. If FilmTec lacks title to the patent, FilmTec has no standing to bring an infringement action under the ’344 patent. FilmTec counters by arguing that the trial court was correct in concluding that the most the Government would have acquired was an equitable title to the ’344 patent, which title would have been made void under 35 U.S.C. § 261 by the subsequent assignment to FilmTec from Cadotte.

The parties agree that Cadotte was employed by MRI and that the contract between MRI and the Government contains a grant of rights to inventions made pursuant to the contract. However, the record does not reflect whether the employment agreement between Cadotte and MRI either granted or required Cadotte to grant to MRI the rights to inventions made by Cadotte. Allied argues that Cadotte’s inventions were assigned nevertheless to MRI. Allied points to the provision in the contract between MRI and the Government in which MRI warrants that it will obligate inventors to assign their rights to MRI.

While this is not conclusive evidence of a grant of or a requirement to grant rights by Cadotte, it raises a serious question about the nature of the title, if any, in FilmTec. FilmTec apparently did not address this issue at the trial, and there is no indication in the opinion of the district court that this gap in the chain of ownership rights was considered by the court.

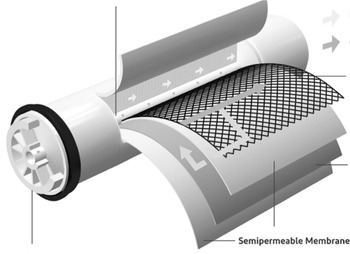

Between the time of an invention and the issuance of a patent, rights in an invention may be assigned and legal title to the ensuing patent will pass to the assignee upon grant of the patent. If an assignment of rights in an invention is made prior to the existence of the invention, this may be viewed as an assignment of an expectant interest. An assignment of an expectant interest can be a valid assignment.

Figure 2.3 FilmTec reverse osmosis membrane filter.

Once the invention is made and an application for patent is filed, however, legal title to the rights accruing thereunder would be in the assignee, and the assignor-inventor would have nothing remaining to assign. In this case, if Cadotte granted MRI rights in inventions made during his employ, and if the subject matter of the ’344 patent was invented by Cadotte during his employ with MRI, then Cadotte had nothing to give to FilmTec and his purported assignment to FilmTec is a nullity. Thus, FilmTec would lack both title to the ’344 patent and standing to bring the present action.

The district court was of the view that if the Government was the assignee from Cadotte through MRI, the Government would have acquired at most an equitable title, and that legal title would remain in Cadotte. The legal title would then have passed to FilmTec by virtue of the later assignment, pursuant to Sec. 261 of the [Patent Act]. Sigma Eng’g v. Halm Instrument, 33 F.R.D. 129 (E.D.N.Y. 1963).

But Sigma, even if it were binding precedent on this court, does not stretch so far. The issue in Sigma was whether the plaintiff, assignee of the patent rights of the inventors, was the real party in interest such as to be able to maintain the instant action for patent infringement. Defendant claimed that the inventors’ employer had title to the invention by virtue of the employment contract which obligated the inventors to transfer all patent rights to inventions made while in its employ. As the court expressly noted, no such transfers were made, however, and the court considered any possible interest held by the employer in the invention to be in the nature of an equitable claim.

In our case, the contract between MRI and the Government did not merely obligate MRI to grant future rights, but expressly granted to the Government MRI’s rights in any future invention. Ordinarily, no further act would be required once an invention came into being; the transfer of title would occur by operation of law. If a similar contract provision existed between Cadotte and MRI, as MRI’s contract with the Government required, and if the invention was made before Cadotte left MRI’s employ, as the trial judge seems to suggest, Cadotte would have no rights in the invention or any ensuing patent to assign to FilmTec.

Because of the district court’s view of the title issue, no specific findings were made on either of these questions. As a result, we do not know who held legal title to the invention and to the patent application and therefore we do not know if FilmTec could make a sufficient legal showing to establish the likelihood of success necessary to support a preliminary injunction.

It is well established that when a legal title holder of a patent transfers his or her title to a third party purchaser for value without notice of an outstanding equitable claim or title, the purchaser takes the entire ownership of the patent, free of any prior equitable encumbrance. This is an application of the common law bona fide purchaser for value rule.

Figure 2.4 Schematic showing possible assignment pathways for Cadotte’s invention.

Section 261 of Title 35 goes a step further. It adopts the principle of the real property recording acts, and provides that the bona fide purchaser for value cuts off the rights of a prior assignee who has failed to record the prior assignment in the Patent and Trademark Office by the dates specified in the statute. Although the statute does not expressly so say, it is clear that the statute is intended to cut off prior legal interests, which the common law rule did not.

Both the common law rule and the statute contemplate that the subsequent purchaser be exactly that—a transferee who pays valuable consideration, and is without notice of the prior transfer. The trial judge, with reference to FilmTec’s rights as a subsequent purchaser, stated simply that “FilmTec is a subsequent purchaser from Cadotte for independent consideration. There is no evidence presented to imply that FilmTec was on notice of any previous assignment.” The court concluded that, even if the MRI contract automatically transferred title to the Government, such assignment is not enforceable at law as it was never recorded.

“the bona fide purchaser for value cuts off the rights of a prior assignee who has failed to record the prior assignment in the Patent and Trademark Office by the dates specified in the statute.”

Since this matter will be before the trial court on remand, it may be useful for us to clarify what is required before FilmTec can properly be considered a subsequent purchaser entitled to the protections of Sec. 261. In the first place, FilmTec must be in fact a purchaser for a valuable consideration. This requirement is different from the classic notion of a purchaser under a deed of grant, where the requirement of consideration was a formality, and the proverbial peppercorn would suffice to have the deed operate under the statute of uses. Here the requirement is that the subsequent purchaser, in order to cut off the rights of the prior purchaser, must be more than a donee or other gratuitous transferee. There must be in fact valuable consideration paid so that the subsequent purchaser can, as a matter of law, claim record reliance as a premise upon which the purchase was made. That, of course, is a matter of proof.

In addition, the subsequent transferee/assignee—FilmTec in our case—must be without notice of any such prior assignment. If Cadotte’s contract with MRI contained a provision assigning any inventions made during the course of employment either to MRI or directly to the Government, Cadotte would clearly be on notice of the provisions of his own contract. Since Cadotte was one of the four founders of FilmTec, and the other founders and officers were also involved at MRI, FilmTec may well be deemed to have had actual notice of an assignment. Given the key roles that Cadotte and the others played both at MRI and later at FilmTec, at a minimum FilmTec might be said to be on inquiry notice of any possible rights in MRI or the Government as a result of Cadotte’s work at MRI. Thus once again, the key to FilmTec’s ability to show a likelihood of success on the merits lies in the relationship between Cadotte and MRI.

In our view of the title issue, it cannot be said on this record that FilmTec has established a reasonable likelihood of success on the merits. It is thus unnecessary for us to consider the other issues raised on appeal concerning the propriety of the injunction. The grant of the preliminary injunction is vacated and the case remanded to the district court to reconsider the propriety of the preliminary injunction and for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

Notes and Questions

1. Recording of title. As noted in Section 2.1, Note 4, assignments of patents may be recorded at the Patent and Trademark Office. As provided in 35 U.S.C. § 261,

An interest that constitutes an assignment, grant or conveyance shall be void as against any subsequent purchaser or mortgagee for a valuable consideration, without notice, unless it is recorded in the Patent and Trademark Office within three months from its date or prior to the date of such subsequent purchase or mortgage.

This provision is a modified form of the familiar “race-notice” recording statute that applies to real estate transactions.Footnote 8 Unlike the comparable provision of the Copyright Act (17 U.S.C. § 205(d), discussed in Section 2.2), the second assignee of a patent may prevail over a prior, unrecorded assignee if the second assignee records first without notice of the earlier assignment unless the first assignee records within three months of the first assignment. An assignee of a patent thus has a three-month grace period in which to record its transfer without fear of being superseded by a second assignment. What is the reason for this three-month grace period, which exists neither in copyright nor real property law?

2. Inquiry notice. The court in FilmTec borrows the notion of “inquiry notice” from the law of real property recording. What is inquiry notice?Footnote 9 How does it differ from actual notice and constructive notice?

3. Present v. Future Grants of Patent Rights. The court in FilmTec explains that “the contract between MRI and the Government did not merely obligate MRI to grant future rights, but expressly granted to the Government MRI’s rights in any future invention. Ordinarily, no further act would be required once an invention came into being; the transfer of title would occur by operation of law.” That is, disregarding MRI’s failure to record the transfer, MRI’s present grant of rights in a future patent to the government (assuming that MRI had previously obtained the requisite rights from Cadotte) would automatically convey those rights to the government as soon as an invention was made.

A similar fact pattern arose in Stanford v. Roche, 563 U.S. 776 (2011) (reproduced, in part, in Section 14.1). In that case, a Stanford researcher who was obligated under Stanford’s policies to assign inventions to Stanford also signed an agreement assigning his future invention rights to Cetus Corp. while visiting the company to use its equipment. The Federal Circuit ruled for Cetus, reasoning that, under FilmTec, the researcher’s present assignment of future patent rights to Cetus automatically became effective when a patent application was filed, leaving nothing for him to assign to the holder of a future promise of assignment (i.e., Stanford). Stanford successfully sought certiorari on different grounds (whether the Bayh–Dole Act overrode these contractual provisions), and the Supreme Court affirmed the judgment for Cetus without reaching the assignment issue.

However, Justices Breyer and Ginsburg dissented (joined by Justice Sotomayor, who concurred in the judgment) on the ground that the Federal Circuit’s 1991 rule in FilmTec seemingly contradicted earlier precedent. Citing one 1867 treatise and a 1958 law review note, Justice Breyer proposed that before FilmTec, “a present assignment of future inventions (as in both contracts here) conveyed equitable, but not legal, title” and that this equitable interest “grants equitable enforcement to an assignment of an expectancy but demands a further act, either reduction to possession or further assignment of the right when it comes into existence.” In other words, the researcher’s present “assignment” of his future patent rights to Cetus would give Cetus an equitable claim to seek “legal title” once an invention existed or a patent application was filed. On this basis, Justice Breyer concludes,

Under this rule, both the initial Stanford and later Cetus agreements would have given rise only to equitable interests in Dr. Holodniy’s invention. And as between these two claims in equity, the facts that Stanford’s contract came first and that Stanford subsequently obtained a postinvention assignment as well should have meant that Stanford, not Cetus, would receive the rights its contract conveyed.

Despite Justice Breyer’s dissatisfaction with the holdings of FilmTec and Stanford v. Roche, their approach to future assignments still appears to be the law.Footnote 10 Which approach do you think most accurately reflects the intentions of the parties? What policy ramifications might each rule have?

4. Shall versus does. The result in Stanford v. Roche turns on the wording of two competing legal instruments – Dr. Holodniy’s assignments to Cetus and Stanford. As noted by the Federal Circuit in the decision below, Holodniy’s initial agreement with Stanford constituted a mere promise to assign his future patent rights to Stanford, whereas his agreement with Cetus acted as a present assignment of his future patent rights to Cetus, thus giving the patent rights to Cetus (583 F.3d 832, 841–842 (2009)). As explained by Justice Breyer in his dissent:Footnote 11

In the earlier agreement—that between Dr. Holodniy and Stanford University—Dr. Holodniy said, “I agree to assign … to Stanford … that right, title and interest in and to … such inventions as required by Contracts and Grants.” In the later agreement—that between Dr. Holodniy and the private research firm Cetus—Dr. Holodniy said, “I will assign and do hereby assign to Cetus, my right, title, and interest in” here relevant “ideas” and “inventions.” The Federal Circuit held that the earlier Stanford agreement’s use of the words “agree to assign,” when compared with the later Cetus agreement’s use of the words “do hereby assign,” made all the difference. It concluded that, once the invention came into existence, the latter words meant that the Cetus agreement trumped the earlier, Stanford agreement. That, in the Circuit’s view, is because the latter words operated upon the invention automatically, while the former did not.

What could Stanford have done to avoid this problem? How do you think the result of Stanford v. Roche affected the wording of university patent policies and assignment documents in general?Footnote 12 Given this holding, should an assignment agreement ever be phrased in any way other than “Assignor hereby grants to Assignee … ”? Was Dr. Holodniy himself at fault in this situation? What, if anything, should he have done differently?

5. Breadth of employee invention assignments. As noted in the introduction to this section, employers who wish to obtain assignments of the inventions created by their employees must do so pursuant to written assignment agreements. But how broad can these assignments be? In Whitewater West Indus. v. Alleshouse, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 36394 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the Federal Circuit reviewed an employee assignment agreement that contained the following provision:

a. Assignment: In consideration of compensation paid by Company, Employee agrees that all right, title and interest in all inventions, improvements, developments, trade-secret, copyrightable or patentable material that Employee conceives or hereafter may make or conceive, whether solely or jointly with others:

(a) with the use of Company’s time, materials, or facilities; or (b) resulting from or suggested by Employee’s work for Company; or (c) in any way connected to any subject matter within the existing or contemplated business of Company

shall automatically be deemed to become the property of Company as soon as made or conceived, and Employee agrees to assign to Company, its successors, assigns, or nominees, all of Employee’s rights and interests in said inventions, improvements, and developments in all countries worldwide. Employee’s obligation to assign the rights to such inventions shall survive the discontinuance or termination of this Agreement for any reason.

This provision, on its face, appears to require not only that current employees assign their inventions to the company (a typical provision in employment agreements), but also that former employees continue to make such assignments indefinitely in the future, so long as such inventions are “in any way connected to any subject matter within the existing or contemplated business of Company.” Needless to say, this provision is quite aggressive.

Richard Alleshouse, a designer of water park attractions, was hired by Wave Loch, Inc., a company operating in California, in October 2007. In September 2008, Alleshouse signed a Covenant Against Disclosure and Covenant Not to Compete containing the above assignment clause. In 2012, Alleshouse left Wave Loch to cofound a new company in the same line of business. There, he continued to develop and patent features of surfing-based water park attractions. In 2017, Wave Loch (through its successor Whitewater West) sued Alleshouse for breach of contract and correction of inventorship, seeking to acquire title to three patents on which Alleshouse was listed as a co-inventor following his departure from Wave Loch.

In evaluating Wave Loch’s claim, the Federal Circuit considered California Business and Professions Code § 16600, which states: “Except as provided in this chapter, every contract by which anyone is restrained from engaging in a lawful profession, trade, or business of any kind is to that extent void.” This statutory provision has traditionally been interpreted to prohibit companies from imposing noncompetition restrictions on former employees. In this case, however, the Federal Circuit extended its reach to prohibit assignments of future IP rights not based on the company’s own IP. In assessing the over-breadth of the provision, the court noted that:

No trade-secret or other confidential information need have been used to conceive the invention or reduce it to practice for the assignment provision to apply. The obligation is unlimited in time and geography. It applies when Mr. Alleshouse’s post-employment invention is merely “suggested by” his work for Wave Loch. It applies, too, when his post-employment invention is “in any way connected to any subject matter” that was within Wave Loch’s “existing or contemplated” business when Mr. Alleshouse worked for Wave Loch.

Under these circumstances, the court invalidated the assignment provision, reasoning that it “imposes [too harsh a] penalty on post-employment professional, trade, or business prospects—a penalty that has undoubted restraining effect on those prospects and that a number of courts have long held to invalidate certain broad agreements with those effects.”

Interestingly, Wave Loch cited Stanford v. Roche in its defense, arguing that the court there interpreted § 16600 to uphold the invention assignment provision used by Cetus. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, however, stating that in Stanford, unlike Whitewater, “there was simply no evidence of a restraining effect on [the researcher’s] ability to engage in his profession.” But as pointed out by Professor Dennis Crouch, “The weak point of the Federal Circuit’s decision [in Whitewater] is that it is seemingly contrary to its own prior express statement [in Stanford] that ‘section 16600 [applies] to employment restrictions on departing employees, not to patent assignments.’”Footnote 13

Which view do you find more persuasive? Should Alleshouse have been required to assign his post-departure patents to Wave Loch? What would the result be in a state that did not have an analog to California’s § 16600? Should this question be resolved under Federal patent law?

6. When does an assignable invention exist? Another twist relating to employee invention assignments involves the point in time when an “invention” actually comes into existence and can thus be assigned. In Bio-Rad Labs, Inc. v. ITC and 10X Genomics (Fed. Cir. 2021), two employees each agreed to assign to Bio-Rad, their employer, any IP, including ideas, discoveries and inventions, that he “conceives, develops or creates” during his employment. Both employees left Bio-Rad to form 10X Genomics, which competed with Bio-Rad. Four months later, 10X began to file patent applications on technology that the employees had worked on while at Bio-Rad. The employees claimed that, while their work at 10X was related to their work at Bio-Rad, they did not actually “conceive” the inventions leading to their patents until after they had joined 10X. The Federal Circuit, applying California employment and contract law, agreed, holding that the assignment clause in the Bio-Rad agreements related to “intellectual property” and that an unprotectable “idea,” even if later leading to a patentable invention, was not IP and could thus not be assigned. That is, the court found that the assignment duty under the agreement was “limited to subject matter that itself could be protected as intellectual property.” If this is the case, then why did the Bio-Rad agreement expressly call for the assignment of “ideas” in addition to inventions and other forms of IP?

Figure 2.5 Richard Alleshouse was the product manager for Wave Loch’s FlowRider attraction, shown here as installed on the upper deck of a Royal Caribbean cruise ship.

Professor Dennis Crouch contrasts Bio-Rad with Dana-Farber Cancer Inst., Inc. v. Ono Pharm. Co., Ltd., 964 F.3d 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2020), in which unpatentable, pre-conception ideas did give rise to a claim for ownership of patentable inventions conceived later.Footnote 14 Which approach do you think most accurately reflects the intentions of the parties? How would you draft an assignment agreement to unambiguously cover pre-conception ideas, or to avoid such assignments?

7. Indivisibility of patent rights. Unlike copyrights (see Section 2.2, Note 5), the rights “within” a patent are indivisible. That is, the owner of a patent may not assign one claim of the patent to another, nor may it assign the exclusive right to make or sell one particular type of product. As set out by the Supreme Court in Waterman v. MacKenzie, 138 U.S. 252 (1891), a patent owner’s only options are to assign (1) the whole patent, (2) an undivided part or share of the whole patent, or (3) the patent rights “within and throughout a specified part of the United States” (a rarity these days). Thus, when a patent owner, under option (2), assigns “an undivided part” of a patent, the assignee receives an undivided interest in the whole, becoming a tenant in common with the original owner and any other co-owners (the rights and duties of such joint patent owners are discussed in greater detail in Section 2.5). Why do patents and copyrights differ in this regard? Should patents be “divisible” like copyrights? What advantages or disadvantages might arise from such divisibility?

8. Past infringement. The general rule in the United States is that “one seeking to recover money damages for infringement of [a] patent … must have held the legal title to the patent during the time of the infringement.” Arachnid, Inc. v. Merit Indus., Inc. 939 F.2d 1574, 1579 (Fed. Cir. 1991). Thus, the assignee of a patent only obtains the right to sue for infringement that occurred while it owned the patent. As the Supreme Court held a century and a half ago, “It is a great mistake to suppose that the assignment of a patent carries with it a transfer of the right to damages for an infringement committed before such assignment.” Moore v. Marsh, 74 U.S. (7 Wall.) 515 (1868). This rule often acts as a trap for the unwary (see, e.g., Nano-Second Technology Co., Ltd. v. Dynaflex International, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 62611 (N.D. Cal.) (language purporting to assign “the entire right, title and interest” to a patent failed to convey the right to sue for past infringement)). As a result, if the assignee wishes to sue for infringement occurring prior to the date of the assignment, the assignment must contain an express conveyance of this right. Does this rule still make sense today? Why might an assignor of a patent not wish to assign the right to sue for past infringement to a purchaser of the patent? What language would you use in an assignment clause to convey this important right to the assignee?

Problem 2.1

The Brokeback Institute (BI) is a leading medical research center. The IP assignment clause in its standard consulting agreement reads as follows:

Consultant hereby assigns to BI all of its ownership, right, title, and interest in and to all Work Product. An Invention will be considered “Work Product” if it fits any of the following three criteria: (1) it is developed using equipment, supplies, facilities, or trade secrets of BI; (2) it results from Consultant’s work for BI; or (3) it relates to BI’s business or its current or anticipated research and development.

How would you react to and/or revise this clause if you represented a consultant who was one of the following:

a. A software developer being engaged by BI for a six-month, full-time engagement to update BI’s medical records software database.

b. A Nobel laureate biochemist with a faculty appointment at Harvard who will be visiting BI to teach a three-week summer class to freshman pre-med students.

c. A brain researcher from Oxford who has been invited to serve on the scientific advisory board of a BI grant-funded neurosurgery project, which will involve participation in one telephonic board meeting per calendar quarter.

d. A pathologist who will advise BI on the design of its new pathology lab, which is expected to require fifty hours of work over the next year.

Problem 2.2

Help out Stanford University by drafting an IP assignment clause applicable to its faculty members, including those who occasionally visit other institutions and companies to use their equipment and facilities.

2.4 Trademark Assignments and Goodwill

Like copyrights and patents, trademarks may be assigned by their owners. But as IP rights, trademarks differ in important respects from copyrights and patents. Most fundamentally, as discussed in the following case, an assignment of a registered trademark is invalid unless it is accompanied by an assignment of the associated business goodwill.

Sugar Busters LLC v. Brennan

177 F.3d 258 (5th Cir. 1999)

KING, Chief Judge

Plaintiff-appellee Sugar Busters, L.L.C. (plaintiff) is a limited liability company organized by three doctors and H. Leighton Steward, who co-authored and published a book entitled “SUGAR BUSTERS! Cut Sugar to Trim Fat” in 1995. In “SUGAR BUSTERS! Cut Sugar to Trim Fat,” the authors recommend a diet plan based on the role of insulin in obesity and cardiovascular disease. The authors’ premise is that reduced consumption of insulin-producing food, such as carbohydrates and other sugars, leads to weight loss and a more healthy lifestyle. The 1995 publication of “SUGAR BUSTERS! Cut Sugar to Trim Fat” sold over 210,000 copies, and in May 1998 a second edition was released. The second edition has sold over 800,000 copies and remains a bestseller.

Brennan then co-authored “SUGAR BUST For Life!,” which was published in May 1998. “SUGAR BUST for Life” states on its cover that it is a “cookbook and companion guide by the famous family of good food,” and that Brennan was “Consultant, Editor, Publisher, [and] Sales and Marketing Director for the original, best-selling ‘Sugar Busters!™ Cut Sugar to Trim Fat.’” Approximately 110,000 copies of “SUGAR BUST for Life!” were sold between its release and September 1998.

Plaintiff filed this suit in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana on May 26, 1998. Plaintiff sought to enjoin [Brennan] from selling, displaying, advertising or distributing “SUGAR BUST for Life!,” to destroy all copies of the cookbook, and to recover damages and any profits derived from the cookbook.

The mark that is the subject of plaintiff’s infringement claim is a service mark that was registered in 1992 by Sugarbusters, Inc., an Indiana corporation operating a retail store named “Sugarbusters” in Indianapolis that provides products and information for diabetics. The “SUGARBUSTERS” service mark, registration number 1,684,769, is for “retail store services featuring products and supplies for diabetic people; namely, medical supplies, medical equipment, food products, informational literature and wearing apparel featuring a message regarding diabetes.” Sugarbusters, Inc. sold “any and all rights to the mark” to Thornton-Sahoo, Inc. on December 19, 1997, and Thornton-Sahoo, Inc. sold these rights to Elliott Company, Inc. (Elliott) on January 9, 1998. Plaintiff obtained the service mark from Elliott pursuant to a “servicemark purchase agreement” dated January 26, 1998. Under the terms of that agreement, plaintiff purchased “all the interests [Elliott] owns” in the mark and “the goodwill of all business connected with the use of and symbolized by” the mark.

The district court found that the mark is valid and that the transfer of the mark to plaintiff was not “in gross” because

[t]he plaintiff has used the trademark to disseminate information through its books, seminars, the Internet, and the cover of plaintiff’s recent book, which reads “Help Treat Diabetes and Other Diseases.” Moreover, the plaintiff is moving forward to market and sell its own products and services, which comport with the products and services sold by the Indiana corporation. There has been a full and complete transfer of the good will related to the mark …

A trademark is merely a symbol of goodwill and has no independent significance apart from the goodwill that it symbolizes. Therefore, a trademark cannot be sold or assigned apart from the goodwill it symbolizes. The sale or assignment of a trademark without the goodwill that the mark represents is characterized as in gross and is invalid.

The purpose of the rule prohibiting the sale or assignment of a trademark in gross is to prevent a consumer from being misled or confused as to the source and nature of the goods or services that he or she acquires. Use of the mark by the assignee in connection with a different goodwill and different product would result in a fraud on the purchasing public who reasonably assume that the mark signifies the same thing, whether used by one person or another. Therefore, if consumers are not to be misled from established associations with the mark, [it must] continue to be associated with the same or similar products after the assignment.

Plaintiff’s purported service mark in “SUGARBUSTERS” is valid only if plaintiff also acquired the goodwill that accompanies the mark; that is, “the portion of the business or service with which the mark is associated.” [Brennan] claim[s] that the transfer of the “SUGARBUSTERS” mark to plaintiff was in gross because “[n]one of the assignor’s underlying business, including its inventory, customer lists, or other assets, were transferred to [plaintiff].” [Brennan’s] view of goodwill, however, is too narrow. Plaintiff may obtain a valid trademark without purchasing any physical or tangible assets of the retail store in Indiana – the transfer of goodwill requires only that the services be sufficiently similar to prevent consumers of the service offered under the mark from being misled from established associations with the mark.

In concluding that goodwill was transferred, the district court relied … on its finding that “plaintiff is moving forward to market and sell its own products and services, which comport with the products and services sold by the Indiana corporation.” Steward testified, however, that plaintiff does not have any plans to operate a retail store, and plaintiff offered no evidence suggesting that it intends to market directly to consumers any goods it licenses to carry the “SUGAR BUSTERS!” name. Finally, we are unconvinced by plaintiff’s argument that, by stating on the cover of its diet book that it may “[h]elp treat diabetes and other diseases” and then selling some of those books on the Internet, plaintiff provides a service substantially similar to a retail store that provides diabetic supplies. We therefore must conclude that plaintiff’s purported service mark is invalid.

Notes and Questions

1. Acquiring goodwill. The Servicemark Purchase Agreement between Elliott and Sugar Busters, LLC clearly purported to transfer “the goodwill of all business connected with the use of and symbolized by” the SUGARBUSTERS mark. Given this language, why did the Fifth Circuit find that the goodwill of the business was not transferred? In view of the court’s holding, how would you advise a client if it desires to acquire a trademark but not to conduct the same business as the prior owner of the mark?

2. Consumer confusion. Generally, trademark infringement cases hinge on whether an alleged infringer is causing consumer confusion as to the source of goods or services. A similar theory applies to the Fifth Circuit’s rule on in gross trademark assignments: If the new goods sold under the mark are significantly different than the old goods sold under the mark, then consumers might be confused as to the source and nature of the goods being sold. Why is this the case? What is the harm in this confusion?

3. Effect of an in gross transfer. Professor Barton Beebe notes, in discussing the Sugar Busters case, that “In most situations … the assignee may claim exclusive rights in the mark, but the basis of and the priority date for those rights stems only from the assignee’s new use of the mark, not from any previous use by the assignor.”Footnote 15 This conclusion is sensible – without the accompanying goodwill, the acquirer gets nothing from the original mark owner, but may begin to use the mark afresh and may build up goodwill based on its own use. But does this reasoning correspond with the holding of Sugar Busters? Note the date on which the plaintiff purported to acquire the trademark from Elliott (January 26, 1998), when Brennan’s allegedly infringing book was released (May 26, 1998) and when the plaintiff brought suit against Brennan (May 26, 1998). Even if the plaintiff acquired no trademark rights at all from Elliott, wouldn’t it have acquired some enforceable rights between January and May, 1998? And what about any common law trademark rights that the plaintiff accrued from the 1995 publication of its first Sugar Busters book?

4. Toward free transfer? Professor Irene Calboli argues that the rule requiring transfer of goodwill with trademarks is an outdated trap for the unwary that should be abolished. She hypothesizes a transaction in which a new company acquires the Coca-Cola Company, observing all the proper formalities, and then decides to apply the famous Coca-Cola mark not to carbonated colas, but to salty snacks. Will consumers be confused? Possibly, but the new owner is perfectly within its rights to apply the mark to its snack products rather than colas. Would consumers be worse off if the transaction documentation had neglected to reflect a transfer of goodwill? Calboli reasons that

the rule of assignment “with goodwill” is failing to meet its purpose and … rather than focusing on a sterile and confusing requirement, the courts should focus directly on the assignee’s use of the mark. If this use is likely to deceive the public, the courts should declare the assignments at issue void. Yet, if no likelihood of confusion or deception results from the transaction, the courts should allow the assignments to stand.Footnote 16

Do you agree? Does the prohibition on in gross transfers of trademarks serve any useful purpose today?Footnote 17

5. Recordation. The recordation requirements for trademarks are similar to those for patents. As provided under 15 U.S.C. § 1060(3):

An assignment shall be void against any subsequent purchaser for valuable consideration without notice, unless the prescribed information reporting the assignment is recorded in the United States Patent and Trademark Office within 3 months after the date of the assignment or prior to the subsequent purchase.

As with patents, this provision is a modified form of “race-notice” recording statute. The second assignee of a trademark may prevail over a prior, unrecorded assignee if the second assignee records first without notice of the earlier assignment unless the first assignee records within three months of the first assignment.

6. Security interests and mortgages. The recording statute for patents 35 U.S.C. § 261 refers to “a subsequent purchaser or mortgagee” of a patent, whereas the statute for trademarks refers only to “a subsequent purchaser.” Why does the trademark statute omit mention of mortgagees? Can a trademark be mortgaged? What might prevent this from happening effectively?

7. Short-form assignments. Intellectual property rights are often conveyed as part of a larger corporate merger or acquisition transaction. In order to avoid filing the entire transaction agreement with the Patent and Trademark Office for recording purposes, the parties often execute a short-form assignment document that pertains only to the assigned patents or trademarks. This short-form document is then recorded at the Patent and Trademark Office. A sample of such a short-form assignment follows.

Short-Form Trademark Assignment (for Filing with the US Patent and Trademark Office)

This assignment is made as of the ____ day of ______________ by ASSIGNOR INC., a _______ corporation having a principal place of business at ______________, hereinafter referred to as the ASSIGNOR, to ASSIGNEE CORP., a ___________ corporation, having a principal place of business at __________________, hereinafter referred to as ASSIGNEE.

WHEREAS, ASSIGNOR is the owner of the registered trademarks and trademark applications, hereinafter collectively referred to as the TRADEMARKS, identified on Schedules “A” and “B” attached hereto, together with the good will and all rights which may have accrued in connection therewith.

WHEREAS, ASSIGNEE is desirous of acquiring the entire right, title and interest of ASSIGNOR in and to said TRADEMARKS together with said rights and the good will of the business symbolized thereby.

NOW, THEREFORE, for good and valuable consideration paid by the ASSIGNEE, receipt of which is hereby acknowledged, ASSIGNOR does hereby sell, assign, transfer and set over to ASSIGNEE, its successors and assigns, ASSIGNOR’s entire right, title and interest in and to the TRADEMARKS, together with said good will of the business symbolized thereby, said TRADEMARKS to be held and enjoyed by the ASSIGNEE, its successors and assigns as fully and entirely as the same would have been held and enjoyed by the ASSIGNOR had this assignment not been made.

ASSIGNOR covenants and agrees to execute such further and confirmatory assignments in recordable form as the ASSIGNEE may reasonably require to vest record title of said respective registrations in ASSIGNEE.

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, ASSIGNOR has caused this Assignment to be executed by a duly authorized officer.

ASSIGNOR

2.5 Assignment of Trade Secrets

Like other IP rights, trade secrets may be assigned by their owners. As the leading treatise on trade secret law announces in the heading of one of its chapters, “Trade Secrets Are Assignable Property.”Footnote 18 Yet the assignment of trade secrets is perhaps the least developed and understood among IP types.

Part of the complexity arises from the fact that the term “trade secret” refers to two distinct concepts: A trade secret is, on one hand, a piece of information that derives value from being kept secret. Yet the term also refers to the set of enforceable legal rights that give the “owner” of that information legal redress for its improper acquisition or usage. In some ways, this dichotomy is similar to that seen with patents and copyrights. On one hand, there is an invention, and on the other hand, a patent right that gives its owner enforceable legal rights with respect to that invention. Likewise, a work of authorship and the copyright in that work of authorship. Unfortunately, trade secrecy law is hobbled by the existence of only a single term to describe both the res that is protected, and the legal mode of its protection.

It is for this reason that the few courts that have considered issues surrounding trade secret assignment have distinguished between “ownership” of a trade secret and its “possession.” In DTM Research, L.L.C. v. AT&T Corp., 245 F.3d 327, 332 (4th Cir. 2001), the court held that “While the information forming the basis of a trade secret can be transferred, as with personal property, its continuing secrecy provides the value, and any general disclosure destroys the value. As a consequence, one ‘owns’ a trade secret when one knows of it, as long as it remains a secret.” Accordingly, the court held that a party possessing secret information is entitled to seek redress against another party that misappropriated it, even if the first party lacks “fee simple” title to that information (i.e., if the first party itself allegedly misappropriated the information from another).

Possession of a trade secret also figures prominently in cases that discuss the assignment of trade secrets. When the owner of a copyrighted work of art transfers the copyright to a buyer, the transferor loses its right to reproduce the work further. Likewise, when the owner of a trade secret transfers that secret to a buyer, the transferor loses its right to exploit that secret further. As the court explained in Memry Corp. v. Ky. Oil Tech., N.V., 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 94393 at *16 (N.D. Cal. 2006), “in giving up all rights to use of the secrets through assignment, the assignor is implicitly and legally bound to maintain the secrecy of the information contained in the trade secrets.”

2.6 Joint Ownership

Just like real and personal property, IP may be co-owned by multiple parties. But the laws regarding joint ownership of IP are different than those affecting real and personal property. To make matters worse, they also differ based on the kind of IP involved, and they vary from country to country. As a result, planning for joint ownership of IP can become fraught with risks and traps for the unwary. As one waggish practitioner has written, “‘Joint ownership of IP’ – no words strike more terror into the heart of an IP practitioner than the task of having to provide appropriate contractual provisions in such a situation.”Footnote 19

Joint ownership of IP rights impacts prosecution of patents and trademarks, exploitation of those rights, and licensing and enforcement of rights. These principles are discussed below in the context of patents, copyrights, trade secrets and trademarks under US law.

2.6.1 Patents

When more than one individual makes an inventive contribution to an invention, the resulting patent will be jointly owned. As explained by the Federal Circuit in Ethicon v. United States Surgical Corp., 135 F.3d 1456, 1465 (Fed. Cir. 1998), “in the context of joint inventorship, each co-inventor presumptively owns a pro rata undivided interest in the entire patent, no matter what their respective contributions.”

The rights of joint owners of patents are described in 35 U.S. Code § 262:

In the absence of any agreement to the contrary, each of the joint owners of a patent may make, use, offer to sell, or sell the patented invention within the United States, or import the patented invention into the United States, without the consent of and without accounting to the other owners.

Thus, each co-owner of a patent may independently exploit the patent without the consent of its co-owners. But unlike copyrights, joint owners of patents do not owe one another a duty of accounting or sharing of profits. Thus, the co-owner of a patented process that uses it to embark on a profitable new manufacturing venture has no obligation to share any of its earnings with the co-owners of the patent.

Any co-owner of a patent may also license it to others, again with no obligation to share royalties or other amounts received with its co-owners.Footnote 20 While a co-owner may grant an exclusive license to a third party, and that exclusivity may operate to prevent the granting co-owner from granting further licenses to others, it has no effect on the other co-owners of the patent, who may continue to exploit or grant other licenses under the patent.

Likewise, any co-owner of a patent may bring suit to enforce it against an infringer, but in order for the suit to proceed, it must join all other co-owners in the suit (see Section 11.1.5). Moreover, as illustrated in Ethicon, a retroactive license from any co-owner will serve to authorize the infringer’s conduct, thus defeating a suit brought by fewer than all co-owners.

2.6.2 Copyrights

There are some similarities between the treatment of joint owners under US copyright and patent law. Under US copyright law, each co-owner of a copyright may independently exploit the copyright without permission of the other co-owners. This exploitation includes performance, reproduction, creation of derivative works and all other exclusive rights afforded by the Copyright Act. However, unlike patents, a copyright co-owner who earns profits from the exploitation of a jointly owned work must render an accounting to his or her co-owners and share the profits with them on a pro rata basis. Thus, if three members of a band compose a song, and one of them quits to pursue a solo career, the soloist must account to the other two for any profits that he or she earns from performing the song (or a derivative of it) for the duration of the copyright.

Likewise, any co-owner of a copyright may license the copyright to others. As with patents, an exclusive license granted by a single co-owner will not be particularly valuable to the licensee, as the other co-owners are free to license the same rights to others. Such an exclusive license will thus be considered nonexclusive for purposes of standing to sue.Footnote 21 As with other exploitation, the copyright licensor must account to the other co-owners for any profits earned based on the license.

Finally, any co-owner of a copyright may sue to enforce the copyright against an infringer without the consent of the other co-owners. As with patents, a license from any co-owner will serve to authorize the infringer’s conduct. But unlike patent infringement litigation, notice to the co-owners of a copyright, and their joinder in an infringement suit, is not mandatory, but discretionary in the court (see 17 U.S.C. § 501(b), discussed in greater detail in Section 11.1.5, Note 5).

2.6.3 Trade Secrets

There is scant case law, and little reliable commentary, discussing the rights and obligations of joint owners of trade secrets to one another. Yet from the authority that exists, it appears that joint owners of trade secrets, unlike joint owners of patents and copyrights, are not free to exploit jointly owned trade secrets without the consent of their co-owners.

Thus, in Morton v. Rank Am., Inc., 812 F. Supp. 1062, 1074 (C.D. Cal. 1993), one co-owner of trade secrets relating to the operations of the Hard Rock Café chain sued another co-owner who used the information in violation of a noncompetition agreement. The court held that, under California law, being the co-owner of a trade secret does not necessarily insulate one from a claim of trade secret misappropriation. In Jardin v. DATAllegro, Inc., 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 84509 *15 (S.D. Cal. 2011), another California court, citing Morton, held that a joint owner of a trade secret could be liable for disclosing the trade secret in a patent application without the permission of his co-owner.