2.1 Introduction

International public administrations (IPAs), that is, the secretariats of international governmental organizations (IGOs) that constitute the international counterparts to administrative bodies at national and subnational levels, have attracted considerable scholarly attention in recent years (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett and Finnemore2004; Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Eckhard, Ege, Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017; Ege and Bauer Reference Ege, Bauer and Reinalda2013; Knill and Bauer Reference Knill and Bauer2016; Liese and Weinlich Reference Liese and Weinlich2006; Thorvaldsdottir, Patz, and Eckhard Reference Thorvaldsdottir, Patz and Eckhard2021). While several studies ascribe an influential role to IPAs in a variety of policy fields (Biermann and Siebenhüner Reference Biermann and Siebenhüner2009; Ege, Bauer, and Wagner Reference Ege, Bauer and Wagner2021; Nay Reference Nay2012; Reinalda and Verbeek Reference Reinalda, Verbeek, Reinalda and Verbeek2004; Skovgaard Reference Skovgaard2017; Stone and Ladi Reference Stone and Ladi2015; Stone and Moloney Reference Stone and Moloney2019), the questions of to what degree and under which precise conditions these bodies influence the making and application of international public policies are still vividly debated (see Eckhard and Ege Reference Eckhard and Ege2016; Ege, Bauer, and Wagner Reference Ege, Bauer and Wagner2020). Given the increasing significance of global environmental challenges as discussed in this book, the question of independent influence is particularly relevant for international environmental bureaucracies (see Chapter 1). Instead of studying the secretariats of multilateral environmental conventions, however, we want to focus on the question of bureaucratic influence of larger and more institutionalized international bureaucracies, which nevertheless play an important role in global environmental governance (see Chapter 9). Comparing the administrations of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which are involved in environmental governance with IPAs in other sectors, gives us the opportunity to determine if environmentally active administrations are characterized by common empirical configurations of style and autonomy and thus can be expected to exhibit a particular policy influence potential.

From a public administration and organizational theory perspective, the role and impact of specific administrative characteristics of international bureaucracies regarding their financial and personnel resources, their competences and expertise, and their specific organizational routines and cultures are of particular interest in the context of this debate (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Eckhard, Ege, Knill, Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017). In this chapter, we hope to add to this debate about potential bureaucratic influence on policymaking beyond the nation-state in conceptual, theoretical, and empirical terms. When speaking about influence, we depart from the “having an effect” definition prominently introduced by Biermann et al. (Reference Biermann, Siebenhüner, Bauer, Biermann and Siebenhüner2009: 41) who defined IPA influence as “the sum of all effects observable for, and attributable to, an international bureaucracy” (see also Liese and Weinlich Reference Liese and Weinlich2006: 504; Weinlich Reference Weinlich2014: 60–61). Yet for our analytical purpose we modify this definition insofar as we consider IPAs’ influence potentials rather than trying to factually distil the degree of administrative influence on a given policy adopted by an IGO (see Bayerlein, Knill, and Steinebach Reference Bayerlein, Knill and Steinebach2020; Knill et al. Reference Knill, Bayerlein, Enkler and Grohs2019). Conceptually, we distinguish between two sources of potential bureaucratic influence, namely formal structural autonomy enjoyed by IPAs and informal behavioral routines as they become apparent in different administrative styles (Davies Reference Davies1967; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Lenz2017; Knill Reference Knill2001; Knill and Grohs Reference Knill, Grohs, Bauer and Trondal2015; Lall Reference Lall2017; Simon Reference Simon1997; Wilson Reference Wilson1989). Structural autonomy and administrative styles are two important aspects (but certainly not the only ones) within the intensively debated explanatory programs with respect to bureaucratic influence: formal administrative structures and informal administrative behavior.

Formal autonomy captures the extent to which an IPA is granted formal competencies and resources to develop and implement public policies. Even though the autonomy concept used here goes beyond formal delegation by also capturing the administrative capacity to develop autonomous preferences (see Bauer, da Conceição-Heldt, and Ege Reference Bauer, da Conceição-Heldt and Ege2015), its operationalization relies on formal organizational characteristics. In this context, researchers typically refer to principal–agent models and highlight the structural relationship between the IPA and its political principals, the member states, expressed in terms of the formal powers and resources member states surrender to the IPA and the control functions they install (Abbott and Snidal Reference Abbott and Snidal1998; Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Lake, Nielson and Tierney2006a; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2015; Jankauskas 2Reference Jankauskas0222; McCubbins, Noll, and Weingast Reference McCubbins, Noll and Weingast1989; Stone Reference Stone2011). In particular, the literature on the rational design of IGOs would expect a higher potential for bureaucratic influence, the higher the levels of formal autonomy of IPAs rise (see, e.g., Ege et al. Reference Ege, Bauer, Wagner and Thomann2023; Haftel and Thompson Reference Haftel and Thompson2006; Johnson Reference Johnson2013; Koremenos, Lipson, and Snidal Reference Koremenos, Lipson and Snidal2001).

Administrative styles, by contrast, capture informal organizational routines that reflect an IPA’s institutionalized orientation both in functional terms (policy effectiveness) and in positional terms (institutional consolidation) (Bayerlein, Knill, and Steinebach Reference Bayerlein, Knill and Steinebach2020). Depending on the prevalence of these orientations, IPAs can be conceived as either servant-oriented (trying to read their mission from the lips of their political masters) or entrepreneurial (actively trying to independently push the policymaking activities of their organization in certain directions). In other words, on a continuum between servant-oriented and entrepreneurial style IPAs, one would expect that the more entrepreneurial an IPA is, the more influential it becomes (Knill et al. Reference Knill, Bayerlein, Enkler and Grohs2019; Nay Reference Nay2012; Oksamytna Reference Oksamytna2018).

We thus take the presumed relationship between autonomy and style, on the one side, and bureaucratic influence, on the other, as our point of departure. However, our prime aim is not to empirically measure and substantiate this relationship but rather to study in more detail how administrative autonomy and administrative style relate to each other in real-world IPAs. This is relevant because with respect to the IPA’s formal capacities and informal routines debates have evolved rather isolated from each other. If a systematic theory of the IPA’s policy influence is the objective, and if informal and formal administrative patterns are of such importance, as many researchers in the field claim, then the question of how these two bureaucratic dimensions relate to each other in the international sphere is of central analytical interest. In theoretical terms, we therefore want to shed light on the relationship between the formal and the informal sources of bureaucratic influence. We illustrate our theoretical considerations with an empirical assessment of these configurations for nine IGO secretariats operating in different policy fields.

Although there are no IPAs with exclusive environmental policy responsibilities in our sample, our approach is particularly relevant for the study of more specialized environmental bureaucracies such as the secretariats of multilateral conventions. Curiously, attempts to measure the formal autonomy and identify the administrative styles of environmental bureaucracies are rare or even nonexistent in the literature (but see Biermann and Siebenhüner Reference Biermann and Siebenhüner2009; Widerberg and van Laerhoven Reference Widerberg and van Laerhoven2014). Probably the most systematic attempt to explain influence of environmental bureaucracies with formal factors relating to the “polity” of these organizations was made by Biermann et al. (Reference Biermann, Siebenhüner, Bauer, Biermann and Siebenhüner2009). While the formal mandate, rules, and so on are mentioned in this seminal work, the organization’s autonomy is not explicitly defined and operationalized as an explanatory variable. Similarly, this work did not explicitly use the concept of administrative styles, although “people and procedures,” including factors such as organizational culture and leadership style, were important variables.

Considering the scarcity of autonomy and style-focused research with respect to international bureaucracies, we believe that the literature on the role and influence of environmental bureaucracies could benefit greatly from adopting the approach presented in this chapter. This seems particularly relevant, first, because of the importance of normative beliefs in the environmental field, which makes a focus on the informal behavior of international civil servants beyond a narrow focus on executive leadership fruitful, and, second, because of the contested nature of costly environmental policies, such as decarbonization strategies, which makes a restriction of formal autonomy of specialized environmental bureaucracies by their principals very likely. In this imaginable context of restricted autonomy combined with deeply rooted normative preferences of IPA staff, our approach can provide an important analytical tool for further research.

Our findings display a variety of configurations. As we will show, there is no clear and dominant pattern in which formal autonomy and administrative styles are linked. A strong and autonomous formal status does not automatically go together with entrepreneurial administrative practices. This is especially visible when looking at the administration of the FAO, UNESCO, and the OECD, which are also active in addressing environmental issues. At the same time, weak autonomy does not necessarily imply that administrative styles reflect a servant type. By shedding light on the complex interactions between formal and informal bureaucratic features, our insights have important implications for the design of accountability mechanisms in view of optimizing bureaucratic control in the international sphere.

The remainder of this chapter is structured as follows: We first present our concepts in more detail to assess formal and informal sources of bureaucratic influence (Section 2.2). We then turn to the theoretical discussion of the relationship between autonomy and administrative styles (Section 2.3). In Section 2.4, we empirically assess different configurations of bureaucratic influence sources within the different IGOs under study. On the basis of our empirical data, we demonstrate how the two concepts link empirically and discuss the relevance and consequence of the emerging patterns – with a particular focus on their potential impact upon policymaking beyond the nation-state.

2.2 Conceptualizing and Measuring Sources of IPAs’ Bureaucratic Influence

There are many conceivable ways to conceptualize and ultimately measure the influence of international bureaucracies. We do not claim exclusivity for the approach we develop here. We do, however, contend that if the internal characteristics of IPAs are put into focus, then formal as well as informal aspects need to be systematically considered. Furthermore, we see a twofold gap in current research in this area: On the one side, disciplined measurement strategies of both formal and informal concepts are often neglected; on the other side, no attempt is made to investigate whether there is a systematic relationship between formal and informal bureaucratic features – and how these relationships may play out in practice. It is against this background that the following heuristic and analytical suggestions are made.

To capture formal sources of bureaucratic influence, we rely on the concept of structural autonomy (Bauer and Ege Reference Bauer and Ege2016a; Ege Reference Ege2017). The informal potential of bureaucratic influence, by contrast, is assessed on the basis of administrative styles developed by Knill, Eckhard, and Grohs (Reference Knill, Eckhard and Grohs2016; see Bayerlein, Knill, and Steinebach Reference Bayerlein, Knill and Steinebach2020). With regard to the formality–informality distinction, the difference between the two concepts is visible not only in their conceptualization but also in their operationalization. While the measurement of autonomy relies on formal characteristics, administrative styles are measured based on administrative self-perceptions by means of semistructured interviews with IPA staff members.

Structural Bureaucratic Autonomy

The concept of bureaucratic autonomy is primarily used in the comparative study of regulatory and executive agencies (see Verhoest et al. Reference Verhoest, Peters, Bouckaert and Verschuere2004). Based on the observation that autonomy “means, above all, to be able to translate one’s own preferences into authoritative actions” (Maggetti and Verhoest Reference Maggetti and Verhoest2014: 239), the concept can also be used to study the structural features of international administrations. To this end, we argue that in order to wield policy influence, a bureaucracy requires the capacity to develop autonomous preferences (autonomy of will) and the ability to translate these preferences into action (autonomy of action) (Bauer and Ege Reference Bauer, Ege, Kim, Ashley and Lambright2014; Caughey, Cohon, and Chatfield Reference Caughey, Cohon and Chatfield2009). To measure bureaucratic autonomy, we use the following eight indicators (each ranging from 0 [low] to 1 [high]), which are then combined into an unweighted additive index (ranging from 0 to 8). After the description of the individual indicators, Table 2.1 will provide a summary of the operationalization of bureaucratic autonomy.

Table 2.1 Measurement of bureaucratic autonomy

| Dimension | Indicator | Operationalization | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy of will | Cohesion | Homogeneity of staff (nationality-based) | Ratio of ten largest nationalities (in terms of staff) to total organizational personnel |

| Administrative permanence | Ratio of staff with open-ended contracts to total number of staff No mobility rules: High Mobility is voluntary but explicitly encouraged: Medium Mobility is mandatory: Low | ||

| Differentiation | Independent leadership | Share of heads of administration recruited from within the organization | |

| Independent research capacities | Centrality of research bodies at different hierarchical levels Existence of a research body at the department level (directly below the SG): High Existence of two or more research bodies at the division level (two hierarchical levels below the SG): Medium high Existence of one research body at the division level (two hierarchical levels below the SG): Medium low No research body at division level or above: Low | ||

| Autonomy of action | Powers | Agenda competences | Degree to which the SG is involved in setting the agenda for legislative meetings SG is responsible for the preparation of the draft agenda and items cannot be removed prior to the actual legislative meeting: High SG is responsible for the preparation of the draft agenda but items can be removed prior to the actual meeting: Medium high The executive body, not the SG, is responsible for the preparation of the draft agenda and items cannot be removed: Medium low The executive body, not the SG, is responsible for the preparation of the draft agenda and items can be removed: Low |

| Sanctioning competences | Sanctioning powers of the organization vis-à-vis its members Autonomous capacity to impose sanctions: High Power to call for sanctions against noncompliant members: Medium high Denial of membership benefits (e.g., voting rights and IGO services): Medium low Only naming and shaming by issuing reports or admonitions: Low | ||

| Resources | Personnel resources | Number of total secretarial staff per policy field Organization employs 1,500 staff or more per policy field: High Organization employs between 1,000 and 1,499 staff per policy field: Medium high Organization employs between 500 and 999 staff per policy field: Medium low Organization employs less than 500 staff per policy field: Low | |

| Financial resources | Degree to which the organization relies on independent sources of income Self-financing: High Mandatory contributions: Medium Voluntary contributions: Low (In case an organization relies on several financial resources, we use the source with the highest share of the budget.) |

To understand the autonomous will of IPAs, one must first consider the fact that bureaucracies are collective actors. Hence, we take into account IPAs’ administrative cohesion, which depends on their staff members’ ability to overcome obstacles to collective action and interact with political actors as a unified organizational entity (Mayntz Reference Mayntz1978: 68). IPAs can be expected to be cohesive if staff members have similar national backgrounds and have been able to stay with the organization over a longer period of time. Second, the development of an autonomous will requires administrative differentiation, which allows staff members to form distinct (administrative) preferences that can potentially differ from those of the political principals. We measure this dimension by considering independent leadership (Cox Reference Cox1969) and independent research capacities (Haas Reference Haas1992) as two important means that facilitate the potential for administrative differentiation in IPAs. While independent leaders can be expected to defend the secretariat’s position against political pressure, independent research capacities are an important means for an administration to develop (and defend) policy options that are different from those of the political actors of the IGO.

In order to be attributed autonomous action capacities that allow the bureaucracy to translate its (potentially distinct) preferences into action, delegation research highlights the relevance of formal powers and independent administrative resources (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2015). The powers of IPAs culminate in the functional role of the Secretary-General (SG) as the organization’s highest civil servant. These powers concern their ability to insert independent proposals into the political process and also the ability of the entire bureaucracy under the SG’s leadership to sanction those who do not comply with organizational rules and norms (Joachim, Reinalda, and Verbeek Reference Joachim, Reinalda and Verbeek2008). Moreover, the resources of an organization need to be sufficiently high, as well as independent from its members. Staffing and funding are the most important resources of public organizations. Thus, having enough of their own staff available to work within a particular issue area and being financially independent from member states and other donors are key features in this respect (Brown Reference Brown2010).

Based on these propositions, Table 2.1 summarizes the indicators used to measure autonomy. A more detailed description of the measurement is presented in Bauer and Ege (Reference Bauer and Ege2016a, Reference Bauer and Egeb). Combining the indicator scores into an additive index creates an autonomy continuum with two extreme poles at the end. Bureaucracies with high structural autonomy have the potential to be particularly influential during policymaking. They combine substantive executive powers and resources with a capacity for independent preference formation and internal cohesion. As such, they constitute a strong administrative counterbalance to the IGO’s political sphere. Autonomous bureaucracies may use their central position to influence policymaking throughout the policy cycle, ranging from policy initiation and drafting to implementation and service delivery. Bureaucracies with low structural autonomy play a relatively passive role during policymaking and only provide technical assistance or monitor tasks either at the IGO’s headquarters or in the organization’s field missions and offices. This may also include executive duties that the IPA implements relatively autonomously, but only for tasks that can be clearly specified by the political principals, for example, through rule-based delegation.

Administrative Styles

The concept of administrative styles emerged in the context of comparative public policy and public administration literature. Administrative styles can generally be defined as stable informal patterns that characterize the behavior and activities of public administrations in the policymaking process (Bayerlein, Knill, and Steinebach Reference Bayerlein, Knill and Steinebach2020; Knill Reference Knill2001; Knill and Grohs Reference Knill, Grohs, Bauer and Trondal2015). Administrative styles manifest themselves in organizational routines and standardized practices and are as such distinct from the deliberate strategic behavior of an IPA’s staff or bureaucratic politics (e.g., Allison Reference Allison1971). Following Knill et al. (Reference Knill, Bayerlein, Enkler and Grohs2019: 85–86, emphasis in original),

we conceive of administrative styles as relatively stable behavioral orientations characterizing an organizational body. It is an institutionalized informal modus operandi that materializes as a guiding principle over time and by repetition, routinization, and subsequent internalization. Under conditions of uncertainty and complexity, individual bureaucrats develop routines for coping with shortages of knowledge, information-processing capacities, and time (Simon, Reference Simon1997). Similarly and depending on their underlying rationale, administrators can develop and internalize behavioral patterns sought to influence their organization’s policies (Knill, Reference Knill2001; Wilson, Reference Wilson1989). We interpret these observable patterns as corresponding to an ideal typical characterization of IPAs’ ‘styles’ in shaping IPA behavior. Rather than restricting our analytical focus on an IPA’s formal position we are thus interested in the extent to which an IPA developed informal routines that allow it to exert influence beyond formal rules or whether its informal activities remain in line with or even behind its formal position.

The study of administrative styles originated from early attempts to “characterize and account for the significantly different ways people carry out relatively standard political/administrative tasks” (Davies Reference Davies1967: 162). Under conditions of uncertainty and complexity, administrators and policymakers develop routines in order to cope with shortages of knowledge, information-processing capacities, and time (Simon Reference Simon1997). At the organizational level, such coping strategies can consolidate into stable patterns of problem-solving behavior (Wilson Reference Wilson1989).

To measure administrative styles at the level of international organizations we analytically differentiate between different patterns of administrative involvement in the initiation, policy formulation, and implementation of policies (Bayerlein, Knill, and Steinebach Reference Bayerlein, Knill and Steinebach2020; Knill, Eckhard, and Grohs Reference Knill, Eckhard and Grohs2016). In each phase, we assess IPA activities along three indicators that capture both functional aspects of technically sound policymaking and political aspects that guarantee alignment with political interests of the principals from an early stage on (Aberbach, Putnam, and Rockman Reference Aberbach, Putnam and Rockman1981; Mayntz and Derlien Reference Mayntz and Derlien1989). After the description of the individual indicators, Table 2.2 will provide a summary of the operationalization of administrative styles.

Table 2.2 Measurement of administrative styles

| Phase | Indicator | Operationalization |

|---|---|---|

| Policy initiation | Mapping of political space | Usually no mapping activities to investigate the IPA’s principals’ preferences at an early stage: Low No clear pattern; occasional mapping activities to investigate the IPA’s principals’ preferences at an early stage: Medium Usually strong mapping activities to investigate the IPA’s principals’ preferences at an early stage: High |

| Support mobilization | Usually no mobilization activities; no active coalition-building exercises to gain external support: Low No clear pattern; occasional mobilizations activities: Medium Usually strong mobilizations activities; active coalition-building exercises to gain external support: High | |

| Issue emergence | Usually outside the bureaucracy: Low No clear pattern; occasionally within the bureaucracy: Medium Usually within bureaucracy: High | |

| Policy drafting | Political anticipation | Usually no functional politicization; the IPA is routinely not sensitive to its political implications: Low No clear pattern; occasional functional politicization: Medium Usually strong functional politicization; the IPA is routinely very sensitive to its political implications: High |

| Solution search | Usually pragmatic drafting with short-cuts or simple heuristics, settling for the first best solution: Low No clear pattern; occasional systematic assessment of the underlying problems and a consideration of alternatives, settling for the optimal solution: Medium Usually systematic assessment of the underlying problems and a consideration of many alternatives, settling for the optimal solution: High | |

| Internal coordination | Usually no efforts to deviate from the default mode of negative coordination: Low No clear pattern; Occasional efforts to deviate from the default mode of negative coordination: Medium Usually strong effort to deviate from the default mode of negative coordination: High | |

| Policy implementation | Strategic use of formal powers | Usually the IPA refrains from open conflicts: Low No clear pattern; occasionally the IPA makes strategic use of its formal power: Medium Usually the IPA makes strategic use of its formal power: High |

| Policy promotion | Usually the IPA makes no efforts to strengthen the impact of organizational outputs: Low No clear pattern; occasionally the IPA makes efforts to strengthen the impact of organizational outputs: Medium Usually the IPA makes strong efforts to strengthen the impact of organizational outputs in every possible way: High | |

| Evaluation efforts | Usually the IPA barely follows the formal evaluation guidelines or does not apply them properly: Low No clear pattern; occasionally the IPA follows the formal evaluation guidelines: Medium Usually the IPA strongly follows the formal evaluation guidelines and makes frequent use of the institutional evaluation mechanisms: High |

During the stage of policy initiation, IPAs might vary in their ambitions to come up with new policy items that should be addressed (issue emergence), to mobilize support for their policies (support mobilization), and to identify the political preferences of their principals with regard to certain initiatives (mapping of political space). In the drafting stage, IPAs might vary in their approach to develop policy solutions (solution search), their efforts placed on internal coordination, and the extent to which they consider the political preferences of their principals when developing their drafts (political anticipation). With regard to the implementation stage, we consider the extent to which IPAs make strategic use of their formal control and sanctioning power, their engagement in policy evaluation, and their ambitions to promote IGOs’ policies in their organizational environment. Overall, we can thus identify nine activities – three for each stage of the policy cycle – in which IPAs regularly have room to maneuver. We suggest all indicators to be equally important for the assessment of an IPA’s administrative style.

For each of these nine activities, we differentiate two extreme poles. One is the policy entrepreneur as stylized by Kingdon (Reference Kingdon1984) and others (Mintrom and Norman Reference Mintrom and Norman2009), an advocate of policy proposals who shows a willingness to invest time and resources in the hope of future return. The policy entrepreneur is highly active in detecting new policy problems and bringing them to the agenda, constantly observing political opportunities, and in strategically mobilizing political or societal support to shape the political agenda. When formulating policy proposals, entrepreneurs are perfectionists in the sense that their proposals are based on a holistic triangulation of the problem at hand, the desired end, and the available resources (Mintzberg Reference Mintzberg1978). As implementers, entrepreneurs are interventionists. Although the secretariat’s sanctioning powers might be limited, bureaucrats can increase their steering capacity by collecting systematic information on policy effects or by developing close relationships with involved stakeholders, interest groups, national administrations, or external experts.

On the other end of the spectrum resides the more pragmatic servant-style administration resembling Max Weber’s ideal-typical conception of bureaucracy as a value-neutral machinery. Servant administrations pursue a “wait-and-see” approach by primarily responding to external policy requests instead of actively exploring windows of opportunity. When formulating policies, we can observe an instrumental and service-oriented role perception and the perpetuation of existing policies in an incremental manner (Lindblom Reference Lindblom1959). From such a perspective, civil servants would do as requested and not question the substance of their tasks, even if they found them to be flawed. In implementation, the servant secretariat relies on a mediating approach. It refrains from observing and trying to improve compliance that goes beyond its legally specified duties, and it relies on nonhierarchical mechanisms of self-regulation. The servant-style IPAs must not necessarily be equated with suboptimal performance or the absence of intentional action per se. It is well possible that a servant-style IPA conceives of itself as a “good” and faithful servant to its political principal and acts accordingly (Boyne and Walker Reference Boyne and Walker2004: 240; Rainey Reference Rainey1997).

Knill et al. (Reference Knill, Bayerlein, Enkler and Grohs2019) provide a more comprehensive discussion of the concept and its determinant, arguing that styles vary depending on the extent to which an IPA is challenged externally (perceived domain challenges, perceived political challenges) and internally (lack of cognitive slack, contested belief systems). Depending on the nature of these challenges, some indicators point to a more entrepreneurial style and others point to servant behavior, thereby reflecting the overall style as being between the two extreme poles. Knill et al. (Reference Knill, Bayerlein, Enkler and Grohs2019) further discuss how the configuration of individual indicator values can be theoretically meaningful. This means that change in styles is possible to the extent that external or internal challenges change, which should occur only gradually.

Table 2.2 summarizes the operationalization of administrative styles. Empirical data was gathered by Bayerlein, Knill, and Steinebach (Reference Bayerlein, Knill and Steinebach2020) on the basis of semistructured expert interviews with 124 individuals at the headquarters of an IGO between 2015 and 2017 (see interview list in Table 2.A1). Each interview lasted between thirty and ninety minutes and followed the list of indicators as presented in Table 2.2. Adjustments were made depending on an interviewee’s job profile. Interviews were recorded and transcribed afterward. Individual questions/statements were coded qualitatively along the operationalization in Table 2.2 on which basis each organization received one value for each indicator, ranging from low to high (see Bayerlein, Knill, and Steinebach Reference Bayerlein, Knill and Steinebach2020, for more details on the data and measurement). For the present purpose, we translate these measures into numerical values (low = 0, medium = 0.5, high = 1) and construct an additive index of administrative styles, with a low overall value representing a servant style and a high overall value representing an entrepreneurial style.

While there is no endogeneity problem in the measurement of the two concepts, one may find a slight conceptual overlap between the dimension “administrative differentiation” (autonomy) and “solution search” (style). Owing to the different means of data collection (staff interviews vs. structural characteristics of the IPA) this should not be much of a problem for the following comparison – also in view of the advantage of being able to systematically study how these two dimensions are related.

2.3 Theoretical Considerations on the Relationship between Formal and Informal Institutions

In the previous section, we suggested two systematic ways to conceive and measure formal and informal characteristics of international bureaucracies. The basis of our theoretical and analytical considerations remains, however, restricted to these concepts. In other words, no orientation emerged as to how the two spheres, the formal and the informal, relate to each other. Conceptualizing the link between the two concepts is the aim of the following paragraphs.

Studying the interplay between formal and informal organizational features is a long-standing and traditional research topic for organizational theorists (see, e.g., Groddeck and Wilz Reference Groddeck and Wilz2015; Tacke Reference Tacke, Groddeck and Wilz2015). In the field of public administration, diverse aspects of the relationship between formal and informal features of organization have been studied, ranging from the interplay between the formal and informal accountability structures (Busuioc and Lodge Reference Busuioc and Lodge2016), and the link between formal discretion and informal behavior of street-level bureaucrats (Lipsky Reference Lipsky1980), to the relationship of formal and actual autonomy of regulatory agencies (Jackson Reference Jackson2014; Maggetti Reference Maggetti2007). In a similar vein, differentiating between formal and informal features of organizations is also prominent in IGO research (Jankauskas Reference Jankauskas2022). Martin (Reference Martin, Hawkins, Lake, Nielson and Tierney2006: 141), for instance, distinguishes “between formal agency, which is the amount of authority states have explicitly delegated to an I[G]O, and informal agency, which is the autonomy an I[G]O has in practice, holding the rules constant.”

Yet while the distinction of formal and informal institutions can be considered as common sense in the relevant literature, the theoretical conception of the relationship between both elements is far from straightforward. In this regard, we can conceive of two scenarios that emphasize either tightly or merely loosely coupled formal and informal arrangements.

Departing from a tight coupling scenario, we expect that the degree of structural autonomy of an IPA should largely determine its administrative styles. In this regard, the most straightforward expectation is that higher autonomy should come along with more entrepreneurial style patterns. Yet the assumption of tight coupling of this kind would factually render the differentiation between formal and informal arrangements obsolete. If informal routines are epiphenomenal to formal institutions, there is no need to study the informal side of the story as no independent explanatory added value is to be expected. Instead, we could simply rely on structural autonomy in order to estimate the potential influence of IPAs on policymaking beyond the nation-state. To additionally look at informal routines would be superfluous.

In fact, the heavy emphasis placed on the distinction between formal and informal institutions in the literature lends strong support to assume a scenario of loose coupling, in which structural autonomy and administrative styles are considered as phenomena independent of each other. The justification for this view emerges from the fact that the literature emphasizes rather different factors that influence variation in terms of formal and informal arrangements. While structural autonomy, for example, is primarily explained against the background of principals’ preferences, institutional path dependencies but also functionalist reasoning (Ege Reference Ege2017; Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Lake, Nielson, Tierney, Hawkins, Lake, Nielson and Tierney2006b; Pierson Reference Pierson2000), informal institutions like administrative styles have their roots in factors like socialization, common professional backgrounds, and administrative perceptions, as well as narratives of external challenges through competition in organizational fields or political threat (Bayerlein, Knill, and Steinebach Reference Bayerlein, Knill and Steinebach2020; Knill Reference Knill2001; Knill, Eckhard, and Grohs Reference Knill, Eckhard and Grohs2016). In short, the fact that different variables account for variation in formal and informal institutions should lead us to conceive of both elements as independent phenomena. Consequently, a highly autonomous IPA does not necessarily need to adopt an entrepreneurial style, while an IPA with low autonomy may not automatically adopt a servant style.

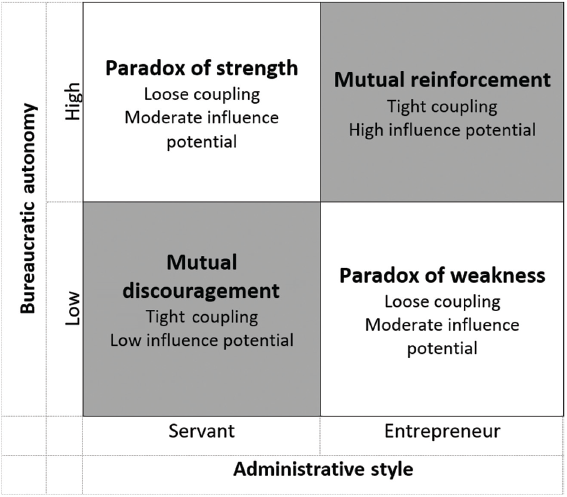

Against these considerations, we can distinguish four ideal-typical configurations of bureaucratic influence potentials. These are based on the differential relationship between formal and informal bureaucratic characteristics in the form of IPA autonomy and styles (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Ideal-typical configurations of formal and informal potentials of bureaucratic policy influence

In line with the conceptual nature of administrative autonomy and administrative styles as outlined earlier, we expect that formal and informal arrangements can reinforce (also in terms of their mutual absence) or weaken each other with regard to an IPA’s potential influence on policymaking. The highest potential for bureaucratic policy influence is expected in constellations in which high structural autonomy is paired with an entrepreneurial administrative style. By contrast, a rather low influence potential can be expected for the combination of low structural autonomy and a servant style shaping informal administrative procedures. A moderate potential for bureaucratic influence can be expected in the two remaining constellations, which are defined by either the combination of high structural autonomy and a servant style or the combination of low structural autonomy and an entrepreneurial style.

While patterns of mutual reinforcement or discouragement at first glance seem straightforward, the other two patterns (the bottom right and the top left corner of Figure 2.1) might be characterized as rather paradoxical. As already argued elsewhere (see Knill, Eckhard, and Grohs Reference Knill, Eckhard and Grohs2016), an IPA with high structural autonomy that develops informal routines that mean the bureaucracy actually remains below its formally available influence potential reflects a paradox of strength. By contrast, an IPA that is formally weak but combines this with a strong entrepreneurial orientation reflects a paradox of weakness. We expect the potential for policymaking influence in both these cases to be moderate, given that either structural or behavioral limitations remain.

There are no reasons to assume a priori that any of these four constellations (as well as any administration between the different extreme poles) is more or less likely to emerge empirically. In particular, we should not expect the constellations mutual reinforcement and mutual discouragement to reflect more stable and more dominant constellations than any other configuration of formal and informal influence potentials. If this were the case, by contrast, we should indeed see a deterministic linkage between formal and informal arrangements – a constellation we would expect neither in light of our theory nor in view of the state of the art in IPA influence research.

A first glance at existing research findings indeed provides support for a rather unsystematic variation of formal and informal influence potentials. Without the aforementioned theoretical roadmap, one could interpret these findings as basically inconsistent. The study of national regulatory agencies is a good illustrative example here: Hanretty and Koop (Reference Hanretty and Koop2013) find support for the reinforcement hypothesis by concluding that formal statutory autonomy is an important determinant of actual independence. However, in practice, Maggetti (Reference Maggetti2007) shows that the two features are largely decoupled from each other. He concludes formal independence is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for explaining variations in the de facto independence of agencies.

The same can be said about research that focuses on the secretariats of IGOs. While it is argued, for instance, that “[d]ifferences in the structure of international bureaucracy afford leading officials with varying degrees of political and procedural influence over the organizations that they manage” (Manulak Reference Manulak2017: 6), the establishment of this link in an empirical manner remains difficult. It can thus be concluded that despite a growing body of literature on IPAs (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett and Finnemore2004; Bauer, Knill, and Eckhard Reference Bauer, Knill and Eckhard2017; Biermann and Siebenhüner Reference Biermann and Siebenhüner2009; Johnson and Urpelainen Reference Johnson and Urpelainen2014), existing research is still inconclusive regarding the extent to which, and how, the bureaucratic structure of international administrations shapes basic behavioral patterns of its staff (see Trondal Reference Trondal2011: 795), as well as which specific structural factors matter most for international bureaucracies’ behavior and their influence on policy output (Eckhard and Ege Reference Eckhard and Ege2016). It is the objective of the following section to investigate such configurations of informal and formal influence potentials of IPAs more systematically.

2.4 Empirical Assessments of the Combination of Formal and Informal Influence Potentials

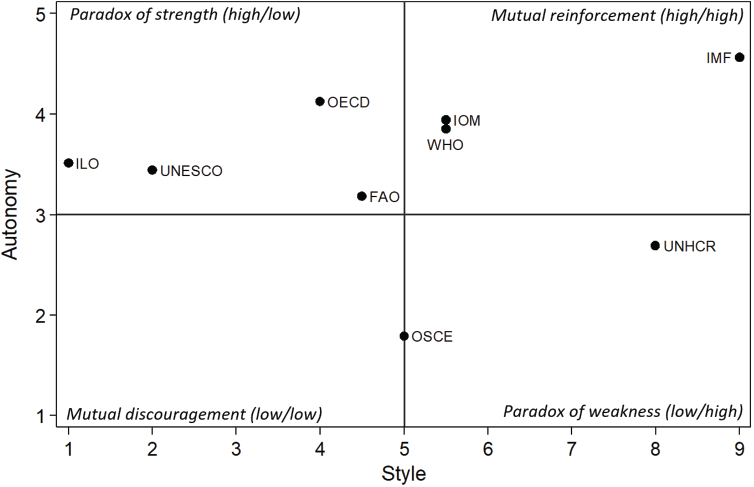

Based on the operationalization of autonomy and styles as outlined above, we have gathered and published empirical data on a large range of IPAs (Bauer and Ege Reference Bauer and Ege2016a; Bayerlein, Knill, and Steinebach Reference Bayerlein, Knill and Steinebach2020; Enkler et al. Reference Enkler, Schmidt, Eckhard, Knill and Grohs2017; Knill, Eckhard, and Grohs Reference Knill, Eckhard and Grohs2016). Our empirical data on structural autonomy and administrative styles spans nine IPAs: ILO, UNESCO, OECD, OSCE, WHO, FAO, IOM, UNHCR, and IMF. While none of these IPAs are purely environmental bureaucracies, three have at least some responsibilities in environmental issues. This is the case with the FAO, which is, for instance, involved in the multistakeholder initiative “Partnership on the environmental benchmarking of livestock supply chains” (LEAP) that aims to improve the environmental performance of livestock supply chains.Footnote 1 Via its natural science sector, UNESCO is also active in environmental issues covering water, ecological science, and earth science.Footnote 2 Finally, the OECD collects a variety of data on environmental issues in its member states and offers it expertise on topics ranging from climate change to biodiversity.Footnote 3

While we do not claim that this sample is representative in a general sense, it includes IPAs with diverse values in many of the dimensions that are usually highlighted as theoretically important – such as membership in the UN system, budget size, number of staff, headquarter or field presence, and policy fields. In the context of this book’s environmental focus, this case selection allows us to compare environmentally active administrations with other IPAs in order to find out if they are characterized by common empirical configurations of style and autonomy.

Figure 2.2 summarizes our aggregate autonomy and style scores for the nine IPAs. Based on their values, we can establish to which of the four theoretical clusters an IPA belongs. While there is no mathematically exact way of doing this, we see on the basis of their distance to one another that IPAs are represented in all fields except the area of mutual discouragement (low/low). We now highlight some exemplary quotes drawn from our interviews to illustrate how – in the context of varying degrees of autonomy – such strategic entrepreneurial or servant behavior plays out empirically in each of the quadrants.

Figure 2.2 Empirical configurations of formal and informal potentials of bureaucratic policy influence

Paradox of weakness – combining low autonomy with an entrepreneurial style: The UNHCR administration’s autonomy is restricted in many ways (visible, e.g., in its low staff homogeneity and low administrative permanence, a lack of centralized research capacities, and weak sanctioning capacities), which is also reflected in the way bureaucrats describe their relation to member states. One interviewee, for example, said: “It would be, in my view, pretty unlikely that we would develop a policy without sufficient consultations either internally or externally. … After all, we are dependent on the financing of some twenty countries around the world. You can’t ignore your stakeholders” (UNHCR 13). Despite their financial dependence and limited structural autonomy, UNHCR staff coherently emphasize that they are not afraid of taking a clear policy position that at times even clashes with key donor interests: “We are not at all averse to conflict. Our first orientation is towards our mandate. That is the role that has been given to us and that we need to fulfil” (UNHCR 10). The key to UNHCR’s entrepreneurial spirit, and this tells much about how IPA policy influence plays out in practice, is a focus on informal bargaining: “Much of our work goes on behind the scenes. When UNHCR makes a public statement of criticism of a government, it’s because we have exhausted each and every level before arriving at that point” (UNHCR 1). This implies that despite their relative restrictive formal powers, UNHCR’s IPA has developed a track record of good bilateral relations and informal partnership with many states that allows them to informally influence policy “behind the scenes.”

Paradox of strength – combining high autonomy with a servant style: The ILO, UNESCO, OECD, and with limitations also the FAO are examples for the opposite scenario of loose coupling with relatively substantial autonomy and servant-style behavioral patterns. For example, the ILO’s autonomy relies mainly on its independent leadership, centralized research divisions, and substantial personnel and financial resources. Because of their comparatively autonomous status, ILO bureaucrats perceive themselves as relatively unchallenged. As one staff member said with a reference to member states: “They need you. They cannot decide not to work with you. … They can’t afford to do that alone. They need the ILO, they need the expertise” (ILO 5). This one-sided dependency allows the bureaucracy to take a back seat instead of actively promoting their own agenda: “If [you ask] most of my colleagues ‘how do we sell ourselves?’ they won’t know. Like they have no reason or objective to sell ILO to anybody” (ILO 14). The situation is similar within UNESCO, as one interviewee who explained UNESCO’s policy planning process detailed: “[T]he secretariat is involved but not in terms of the design process. I don’t think it is our role…. It is a country-driven process” (UNESCO 3). It is similar in the OECD too, where an official said that it “is very important for us to keep regular contact with the member states … you can really see what the problems and topics are and then we make our proposals for the work program out of that” (OECD 7). Bureaucrats in all four organizations thus wait for request instead of developing their own ideas and convincing others to turn them into policy or to implement them. One interviewee said with an eye on their policy engagement that “[it is] less mapping of the political space. It is mostly responding to requests” (ILO 4). Another respondent said that “we are the pen holders, we do as told” (ILO 10). Finally, the servant strategy implies that all IPAs refrain from exerting pressure on member states or taking sides. For instance, when it comes to the implementation of their recommendations, the OECD remains very soft: “[A]t the moment we sort of hand over the report and we don’t come back to it” (OECD 8). ILO bureaucrats avoid taking sides by fostering one or the other policy position or brokering coalitions behind the scenes: “I wouldn’t say we are trying to build up pressure. In fact, we are often seen as a neutral party in these kinds of things. That’s the added value of the ILO … we are not promoting any particular agenda” (ILO 14). A UNESCO staff member said that it is often “difficult to change partners so you … simply report that it unfortunately wasn’t possible” (UNESCO 5). All in all, this shows that these IPAs do not exploit the potential influence they gain through their structural autonomy.

Mutual reinforcement – combining high autonomy with an entrepreneurial style: The IMF, which is based in Washington, DC, is the clearest example in our sample of an IPA with both an entrepreneurial style and high autonomy values. The IMF is responsible for overseeing and safeguarding the stability of the international monetary and financial system and has 189 member countries (International Monetary Fund 2017). The IMF administration’s autonomy is, in comparison to others, mainly a result of high administrative permanence, strong research capacities, relatively strong sanctioning capacities, and independent financing. The IMF has significant formal powers (Lang and Presbitero Reference Lang and Presbitero2018), which is also how its personnel perceive it: “While [other IGOs] may actually be much stronger on some topics than the Fund, for example climate change, the Fund still gets more attention and recognition in this area…. This really shows the power of the Fund” (IMF 7). Interestingly, this does not coincide with a behavioral pattern of neutrality and response, as in the ILO or UNESCO. Instead, the IMF IPA is characterized by an entrepreneurial style with respondents frankly admitting that they do take sides and promote certain policy positions: “[T]he only way to implement (certain policies) is to convince the authorities that it is something good for them to do. We also try to build a consensus around certain policies, and if most countries are on board with it we can tell the remaining ones ‘you are the only ones not doing this’” (IMF 2). Another respondent said that

at the IMF it is very different from my previous work [at another IGO]. There, we may not have liked the decisions the principals made, but we knew that was the place where the decisions were made. The way I see it here, staff think they could make the decisions themselves, so why should they trust the top management or the Board [i.e., member states, the authors] to make the right decisions?

Mutual discouragement – combining low autonomy with a servant style: Even though the OSCE with its low autonomy and medium entrepreneurism comes closest to this configuration, a clear empirical manifestation of this ideal-type is missing in our sample. It is puzzling that the configuration that most closely resembles the idea of IGOs that has for decades been predominant in theorizing in international relations is absent empirically. We can only speculate as to whether this is a peculiarity of our case selection or indicative of a broader phenomenon. While this result may raise doubts about the representativeness of our sample, it is also possible that an IPA in this quadrant is generally of limited use for IGO members – as a certain degree of autonomy is a functional requirement for an IPA to fulfil its tasks in the first place (Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Lake, Nielson, Tierney, Hawkins, Lake, Nielson and Tierney2006b: 13; Mayntz Reference Mayntz1978: 66–67). Thus, in the absence of structural autonomy, an IPA may be able to actively compensate this precarious situation by developing a particularly entrepreneurial behavior to eventually justify its existence to the members. Thus, the lack of empirical cases in this field could indicate that informal and formal factors of IPAs are not fully independent of each other but that the informal administrative style can be interpreted as strategic reaction to predetermined formal context factors. This would explain why we find this “paradoxical” combination. To further substantiate this argument, however, the sample needs to be extended to include more low-autonomy organizations.

2.5 Conclusion

In this chapter we argued that if a theory of international bureaucratic influence is the aim, we have to disentangle the relationship between formal and informal administrative characteristics in view of the resulting potential for administrative impact on policymaking. Therefore, we revisited the controversial debate about the relationship between formal and informal features of public administrations. We presented concepts to identify and measure structural autonomy (an example of formal characteristics) and administrative styles (an example of informal routines) of international public administrations. By mapping empirical intensities of structural autonomy as well as the occurrence of (entrepreneurial or servant-like) styles, we identified four constellations of the relationship between these formal and informal characteristics. More specifically, we have asked whether the relationship is characterized predominantly by tight or loose coupling of the two concepts and applied our theoretical considerations by means of an empirical assessment of autonomy and styles in nine IPAs. Moreover, we used interview quotations from the UNHCR, ILO, and IMF administrations to illustrate the empirical existence of these combinations.

Our findings display no dominant pattern in which formal autonomy and informal styles are linked. In the majority of our cases, however, we observe a loose coupling of the two features, implying what we call the paradox of strength and weakness rather than mutual reinforcement or discouragement. Thus, our findings indicate that formal autonomy does not determine administrative styles. Rather formal autonomy and administrative styles are best considered as influence potentials that evolve and operate independent of each other. Consequently, we cannot simply rely on structural autonomy in order to estimate the potential influence of IPAs. Instead, in order to explain IPA influence on policymaking beyond the nation-state, the two aspects need to be conceptualized separately and linked empirically. These findings have important implications. First, the case of UNHCR indicates that IPAs are capable of entrepreneurial informal reactions to situations of precarious structural autonomy. This supports previous arguments made with regard to the OSCE (Knill, Eckhard, and Grohs Reference Knill, Eckhard and Grohs2016) and provides further evidence that such a paradox of weakness may indeed be a more common feature of structurally weak administrations. Second, our insights have important implications for the design of accountability mechanisms in view of optimizing bureaucratic control in the international sphere. The finding that formal autonomy and informal styles work relatively independent of each other emphasizes that formal control and oversight in IGOs (Grigorescu Reference Grigorescu2010) may be effective only if supplemented by more informal means of securing accountability. Otherwise, member states as the collective principals may indeed be faced with a runaway bureaucracy (Elsig Reference Elsig2007). A growing body of research on the ways member states seek representation in IPA staff bodies and thereby enact control and influence (Eckhard and Dijkstra Reference Eckhard and Dijkstra2017; Eckhard and Steinebach Reference Eckhard and Steinebach2021; Manulak Reference Manulak2017; Urpelainen Reference Urpelainen2012) is indicative of this argument. Third, and this is particularly relevant in the context of this book, our findings show that all three environmentally active IPAs studied here are characterized by a loose coupling of style and autonomy, leading to what we describe as a paradox of strength. While such a combination of high autonomy and a servant style may result in a formally influential but often rather passive role played by the three IPAs, this finding suggests that it is particularly important for other organizations populating the global administrative space in environmental governance to step in and take initiative. The chapters of this volume show that multilateral environmental convention secretariats seem to have especially taken on this challenge and over time have become more entrepreneurial, attention-seeking, and influential.

Even though we did not study these secretariats in this chapter, we argue that owing to the nature of (global) environmental policy, investigating environmental convention secretariats’ autonomy and styles (as well as the relationship between the two means of influence) is promising. First efforts to apply the concepts presented here have been made. For instance, a recent study analyzes the administrative styles of the climate secretariat in the run-up to the Paris Agreement and during the course of its implementation (Saerbeck et al. Reference Saerbeck, Well, Jörgens, Goritz and Kolleck2020).

In this chapter, we focused on intrabureaucratic factors and the question of how they are related to each other in view of the administrative potential to influence international policymaking. Thus, a word of caution is in order. Studying bureaucratic influence by putting formal and informal organizational features center stage is not to deny that there are many other factors such as organizational leadership, member states’ political agendas, situational staff preferences, the structure of the underlying problem, or external events that need to be considered, if in empirical cases the concrete or de facto influence of an international bureaucracy is to be established in particular cases. In their seminal work on the influence of the managers of global change, Biermann and Siebenhüner (Reference Biermann and Siebenhüner2009) have provided a realistic design for studying such bureaucratic impact covering a broad range of factors. Even more than a decade later, empirical research can rely on their conceptual blueprint. Our modest contribution in this chapter is intended to complement this work by advancing on the intraorganizational side of the story. Thus, future research may want to investigate why and when reinforcement and discouragement takes place and how the different constellations can be interpreted in terms of bureaucratic influence. While we could only hypothesize how the two features impact on bureaucratic influence, this nexus should be explored empirically by conceptualizing influence as a separate dependent variable.