Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword: Let It Get into You

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: On Intimate Entanglements

- Chapter One Yusef 's Breath: Jazz Love, Cross-Racial Identification, and Paying Dues

- Chapter Two Three Reflections, with Epilogue

- Chapter Three Modulating Flawed Bodies: Intimate Acoustemologies, Chronic Pain, and Ethnographic Pianism

- Chapter Four Performing Desire: Race, Sex, and the Ethnographic Encounter

- Chapter Five Thick Descriptions

- Chapter Six Entering the Lives of Others: Entangled Intimacies, Trauma, and Performance

- Chapter Seven Ethnomusicological Empathy: Excavating a Black Graduate Student’s Heartland

- Chapter Eight Ethnomusicological Becoming: Deep Listening as Erotics in the Field

- Chapter Nine Mirror Dancing in Congo: Reflections on Fieldwork as Blanche Neige

- Chapter Ten Ethnography and its Double(s): Theorizing the Personal with Jews in Ghana

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

Chapter Nine - Mirror Dancing in Congo: Reflections on Fieldwork as Blanche Neige

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 January 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword: Let It Get into You

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: On Intimate Entanglements

- Chapter One Yusef 's Breath: Jazz Love, Cross-Racial Identification, and Paying Dues

- Chapter Two Three Reflections, with Epilogue

- Chapter Three Modulating Flawed Bodies: Intimate Acoustemologies, Chronic Pain, and Ethnographic Pianism

- Chapter Four Performing Desire: Race, Sex, and the Ethnographic Encounter

- Chapter Five Thick Descriptions

- Chapter Six Entering the Lives of Others: Entangled Intimacies, Trauma, and Performance

- Chapter Seven Ethnomusicological Empathy: Excavating a Black Graduate Student’s Heartland

- Chapter Eight Ethnomusicological Becoming: Deep Listening as Erotics in the Field

- Chapter Nine Mirror Dancing in Congo: Reflections on Fieldwork as Blanche Neige

- Chapter Ten Ethnography and its Double(s): Theorizing the Personal with Jews in Ghana

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

Summary

As the drummer hits the cymbal, the dancer pivots on her front foot with her arm raised above her head, marking le passage, the passage beat. She turns to intently face the crowd while vigorously rotating her hips in a movement originating from the knees. Shrugging her shoulders rhythmically upwards, head cocked to the side, she holds her arms to her rib cage, locating the center of movement. She is stoic; her facial expression is fixed but not emotionless. The drummer embellishes each subsequent movement in the choreographic sequence, carefully keeping watch, predicting her next move. I watch her too, from the side wings of the stage where I wait with the other dancers for her solo to finish. The audience explodes with cheers when she leaps into the air at the moment when the music reaches an ecstatic crescendo, her hands clapping shut above her body as if to catch something visible only to her. This concert, not unlike other concerts across the sprawling city of Kinshasa, is incomplete without the presence of stage dancers, or danseuses. And it is in this expressive milieu that women are the most visible performers in the city, and where their bravado is felt.

I am also a danseuse in the band. Though like the others, I was given the stage name Blanche Neige, I feel more like a clown and an other. I am a far cry from the celebrated image of femininity in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, as I am bony and do not move with the same elegance and mastery as the others. Nevertheless, the band invites me to rehearse and perform with them several times a week. I muddle through entrainement (training), doing my best to learn the routines. My main preoccupation is not so much to pass as a professional dancer as it is to spend time with the dancers, build relationships with them, and to better understand this mode of work that these young women have chosen to devote themselves to. Every ethnographer strives for cultural intimacy, and I approached this through the sensuousness of dance, reflected back to me in and through my own participation.

Filip De Boeck, an urban anthropologist of Congo writes, “The manner of production of space and time in the city is thus inextricably connected with the production of the body.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

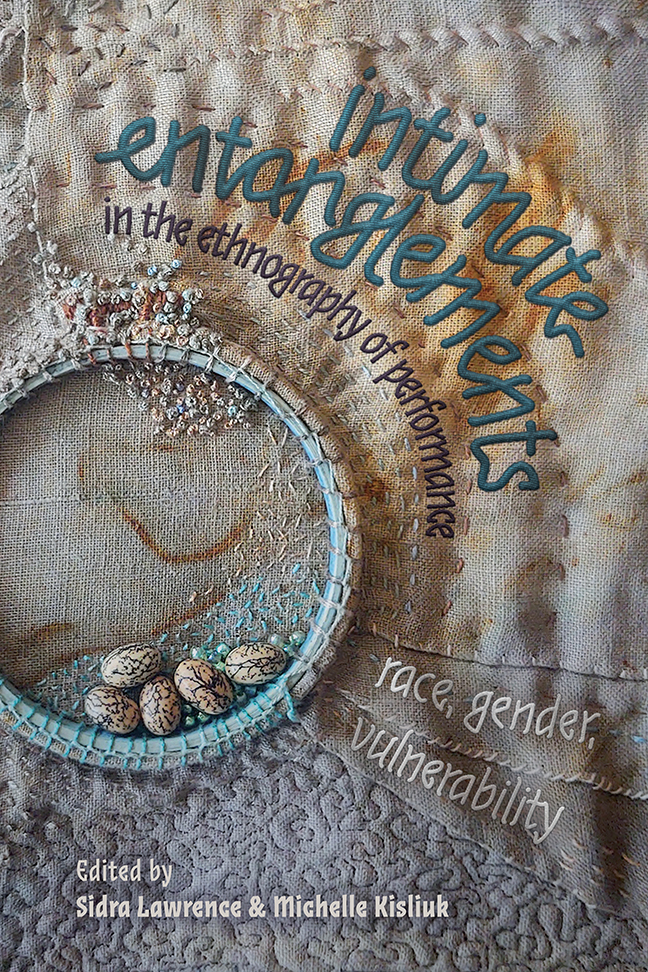

- Intimate Entanglements in the Ethnography of PerformanceRace, Gender, Vulnerability, pp. 175 - 193Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2023