Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword: Let It Get into You

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: On Intimate Entanglements

- Chapter One Yusef 's Breath: Jazz Love, Cross-Racial Identification, and Paying Dues

- Chapter Two Three Reflections, with Epilogue

- Chapter Three Modulating Flawed Bodies: Intimate Acoustemologies, Chronic Pain, and Ethnographic Pianism

- Chapter Four Performing Desire: Race, Sex, and the Ethnographic Encounter

- Chapter Five Thick Descriptions

- Chapter Six Entering the Lives of Others: Entangled Intimacies, Trauma, and Performance

- Chapter Seven Ethnomusicological Empathy: Excavating a Black Graduate Student’s Heartland

- Chapter Eight Ethnomusicological Becoming: Deep Listening as Erotics in the Field

- Chapter Nine Mirror Dancing in Congo: Reflections on Fieldwork as Blanche Neige

- Chapter Ten Ethnography and its Double(s): Theorizing the Personal with Jews in Ghana

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

Chapter One - Yusef 's Breath: Jazz Love, Cross-Racial Identification, and Paying Dues

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 January 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword: Let It Get into You

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: On Intimate Entanglements

- Chapter One Yusef 's Breath: Jazz Love, Cross-Racial Identification, and Paying Dues

- Chapter Two Three Reflections, with Epilogue

- Chapter Three Modulating Flawed Bodies: Intimate Acoustemologies, Chronic Pain, and Ethnographic Pianism

- Chapter Four Performing Desire: Race, Sex, and the Ethnographic Encounter

- Chapter Five Thick Descriptions

- Chapter Six Entering the Lives of Others: Entangled Intimacies, Trauma, and Performance

- Chapter Seven Ethnomusicological Empathy: Excavating a Black Graduate Student’s Heartland

- Chapter Eight Ethnomusicological Becoming: Deep Listening as Erotics in the Field

- Chapter Nine Mirror Dancing in Congo: Reflections on Fieldwork as Blanche Neige

- Chapter Ten Ethnography and its Double(s): Theorizing the Personal with Jews in Ghana

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

Summary

Freedom and innocence are antithetical. You can't have both.

—James BaldwinI used to think I was a fast learner. Indeed, I could understand concepts quickly, but only because I was so able to ignore the particulars. I was a bullet train toward my destination, the landscape out the windows blurred into invisibility. It was many years into practicing Buddhism, years after one of my Buddhist teachers described herself as a slow learner and I felt smugly relieved to not have that problem, that I realized I, too, was slow. Glossing quickly over the surface, I held more complex engagement at a distance, essentially afraid to lose myself within something—because how could I judge then? How could I know I was smart, that is, smarter than others, if I could not locate myself for comparison?

Along with Buddhism, my road to more realistically assessing my capacities included my efforts to learn jazz. I had loved the saxophone since the age I began playing in my Fairbanks, Alaska, junior high school “jazz” band, even as my primary exposure was “String of Pearls” by way of the Glenn Miller Orchestra, Phil Woods's alto saxophone solo on Billy Joel's Just the Way You Are, and the 1970s instrumental pop group Spyro Gyra, which I dutifully transcribed with earnest and rotund eighth notes for my first gigs in a prom band. I’m sad to say that it was only after I graduated from college that I encountered what I think I can call fairly unproblematically “real” jazz. I had given up the saxophone my senior year of high school and still recall the moment outside the band room when I had the thought: this is not what grown women do. But I would tear up when I’d hear a saxophone on a pop song in college. If I had kept it up, I hope I would have discovered jazz in college. But it was only after graduating that I encountered a bevy of young, white, male, experimental-minded recent college grads in San Francisco who listened to Coltrane, Miles, Ornette, Dolphy, and Ayler and dragged refuse into their rented flats to bang on in improvisatory and drug-fueled splendor day and night.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

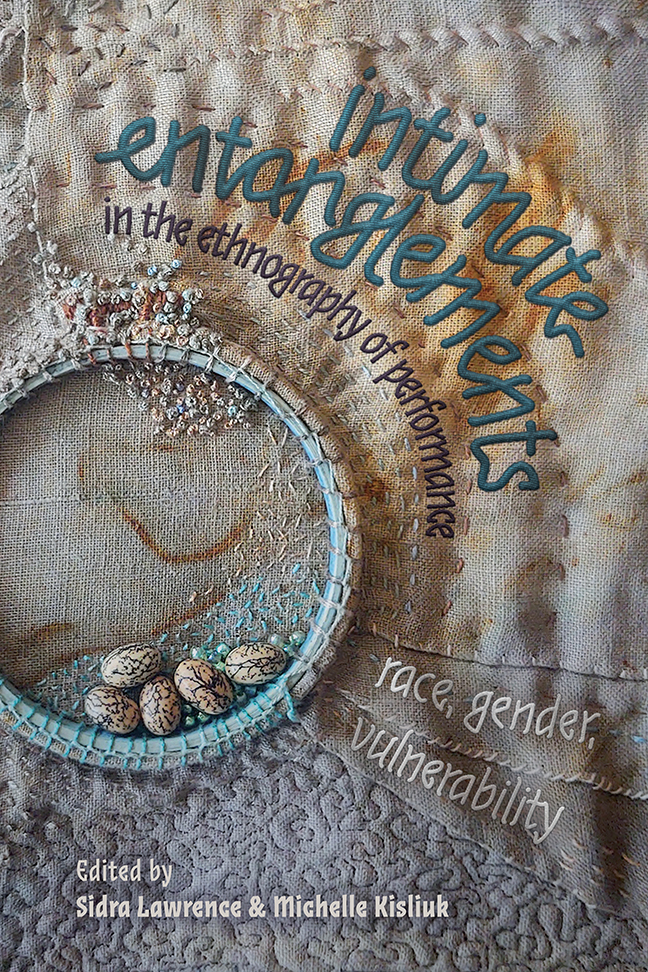

- Intimate Entanglements in the Ethnography of PerformanceRace, Gender, Vulnerability, pp. 23 - 46Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2023