I Introduction

After independence in 1971, the banking industry in Bangladesh started its journey with six nationalised commercial banks (NCBs), three state-owned specialised banks, and nine foreign banks. In the 1980s, the industry achieved significant expansion with the entrance of private banks. Banks in Bangladesh come under two broad categories: scheduled and non-scheduled banks. Banks that have a licence to operate under the Bank Company Act, 1991 (amended in 2013 and in 2018) are termed scheduled banks and banks that are established for specific objectives and operate under the acts that are enacted to meet those objectives are called non-scheduled banks. As at March 2020, there were 60 scheduled and 5 non-scheduled banks in Bangladesh.Footnote 1

Although the direct contribution of the banking sector to the gross domestic product (GDP) of Bangladesh is only around 3% (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, 2017), there are a number of avenues through which the banking sector has important implications for economic growth and development in Bangladesh. Despite issues related to weak institutions and governance (which are discussed in this chapter), the banking sector has helped move the major sectors of the economy, that is the ready-made garments (RMG) sector, remittances, and agriculture.Footnote 2 As a result, over the past decades, the country has witnessed a high rate of economic growth, especially in the past decade, when growth was more than 6.5% per annum. There is a paradox in achieving such a consistently high growth numbers amidst the institutional weaknesses in the financial sector. One explanation of this could be found by looking at the distribution of loans by sectors – the RMG sector, as well as certain big industries (mainly the import substituting industries, e.g. cement, steel, textiles), constitute a significant proportion of the loans being disbursed.Footnote 3 With the RMG sector being one of the crucial growth drivers of the economy, weaknesses in the banking sector have not been reflected strongly in terms of growth numbers. It is primarily other export-oriented non-RMG sectors – for example leather, agro-processing, information and communication technology (ICT), and other sectors – which are being affected by such elite capture of loans.Footnote 4

High non-performing loans (NPLs)Footnote 5 in the banking sector reduce the capital of the banking sector, creating a fiscal burden and affecting banks’ profitability and interest rates, and generating an unfavourable impact on overall private sector investment. All these issues are undermining economic and export diversification prospects, as well as future economic growth prospects. With an almost stagnant private investment to GDP ratio of around 22% over the past decade, the high interest rates prevailing in the banking sector are often argued to be one of the crucial obstacles to boosting private investment. In this context, high NPLs constrain banks’ ability to offer loans at lower interest rates, resulting in a high cost of investment.

It is also important to mention that, given the resource constraints, the current trend of significant budgetary allocation for the recapitalisation of inefficient public banks tends to have negative effects on the volume of investment for the development of the country. Also, NPLs have been associated with loan defaulters laundering funds abroad.

The banking sector in Bangladesh suffers from some inherent weaknesses. According to the banking system z-score,Footnote 6 in 2017, Bangladesh scored only 6.7 and ranked 147th out of 179 countries. In 2017, Bangladesh had the lowest z-score among the South Asian countries. The institutional and governance-related challenges in the banking sector in Bangladesh include regulatory and policy capture, political patronage-based governance, provision of incentives through monetary injections to the state-owned banks, and lack of autonomy of the central bank. In this context, the rising NPLs are a manifestation of institutional problems that are prevalent in this sector.

Against this backdrop, this chapter provides an overview of the performance and challenges of the banking sector in Bangladesh by looking at: the structure of the banking sector; different performance indicators of the banking sector related to access, stability, efficiency, and depth; the trend in NPLs; efficiency levels of private banks; and the development implications of the status of the banking sector. This chapter also explores the politics of the banking sector and avenues of governance failures in relation to private commercial banks in Bangladesh. This chapter is organised as follows: Section II reviews relevant literature; Section III provides an overview of the key indicators related to the performance and challenges of the banking sector in Bangladesh; Section IV presents a brief history of the politics of the banking sector; Section V provides an analytical narrative of the governance failure in the banking sector; and, finally, Section VI summarises the findings and offers a few recommendations.

II Review of Literature on the Banking Sector of Bangladesh

In terms of the quantitative indicators for assessing banks’ performance, the existing literature has utilised a number of indicators. For example, one of the important indicators of banks’ performance is the CAMELS ratio, which, as the name suggests, encompasses a number of key performance indicators: capital adequacy, asset quality, management, earning, liquidity, and sensitivity to market risks. Based on the assessment of related indicators of CAMELS, Iqbal et al. (Reference Iqbal, Vankatesh, Jongwanich and Badir2012) concluded that development financial institutions (DFIs)Footnote 7 are in the most vulnerable position, while foreign commercial banks (FCBs)Footnote 8 are in the best situation in Bangladesh.

Nguyen and Ali (Reference Nguyen and Ali2011) highlighted the challenges of the financial sector and commented that the key issue in regard to the financial sector’s challenges is lack of competition and a resulting lack of market discipline. In this connection, the authors emphasised the importance of institutional irregularities – for example excessive government intervention, corruption and political intervention, as well as managerial inefficiencies – as the root causes of different problems. Mansur (Reference Mansur2015) also emphasised the lack of corporate governance of banks, which are closely related to political connections. Although he expressed concern over the skyrocketing numbers of NPLs, he considered NPLs of public banks to be a greater danger to the economy.

While exploring the factors affecting the profitability of banks, Rahman et al. (Reference Rahman, Hamid and Khan2015) found that capital strength (both regulatory capital and equity capital) and loan intensity (captured through liquidity – defined as the ratio of total loans to total assets) have a positive and significant impact, whereas cost-efficiency (ratio of cost to income) and off-balance sheet activities have a negative and significant impact on bank profitability. From a technical point of view, Hossain (Reference Hossain2012), using data of individual banks, applied the Arellano–Bond panel regression method and attempted to explain a relevant yet slightly different issue of the persistency of high interest rate spread. In addition, he also tried to explain the reason behind different interest rate spreads of different banks, despite the financial reform initiatives during the 1990s. According to Hossain, key determinants of the high interest rate spread are high operating costs, NPLs, market power, and segmented credit and deposit markets.

The status of NPLs in the banking sector of Bangladesh since the adoption of a new loan classification and provisioning system in 1990s has been examined by Adhikary (Reference Adhikary2006). The analysis indicates that an alarming amount of NPLs, both in NCBs and in DFIs, along with the practice of maintaining deficient loan-loss provisions, have a negative impact on the overall credit quality in Bangladesh. The author concluded that, though Bangladesh has made progress in ratifying international standards of loan classification and provisioning, the overall management of NPLs is ineffective.

Against the backdrop of the privatisation of NCBs, Beck and Rahman (Reference Beck and Rahman2006) concluded that, to ensure a viable long-term expansion of the financial system, the role of the government is critical and in Bangladesh the Government should play the role of a facilitator, instead of that of an operator. In this context, the authors also recommended that, in addition to divestment from government-owned banks, de-politicisation of the certificating process, and formulation of a market-based bank failure resolution framework, concentrating on intermediation is required for an efficient financial system. Their recommendations also emphasised that the Government should divert from the practice of serving as the implicit guarantee for depositors and owners, and rather start moving towards the practice of involving market participants to monitor and discipline banks. According to the authors, this practice should be extended to other parts of the financial sector, for example micro enterprises and the capital market. However, these suggestions have not been taken into consideration effectively in the financial sector reform process in Bangladesh.

Beck (Reference Beck2008) emphasised the importance of the degree of competition of banks in Bangladesh. According to the author, fragility in the banking sector in Bangladesh in the period reviewed was not related to liberalisation of the sector per se, rather it was connected to regulatory and supervisory issues. Therefore, in order to materialise the benefits of competition, the author saw a need to abide by essential institutional frameworks. Where there is weak institutional framework, according to Beck (Reference Beck2008), unchecked competition can lead to a fragile banking sector. As a remedy, instead of curbing competitive practices, Beck argued that the Government should emphasise improving the institutional environment and opt for an incentive-motivated banking sector. Hossain (Reference Hossain2012) also expressed concern over efficiency and competition in the banking sector and concluded that the reform programmes initiated in the 1990s had not been able to generate this in Bangladesh.

Robin et al. (Reference Robin, Salim and Bloch2017) applied stochastic frontier analysis to bank-level data of Bangladesh for the period 1983–2012, along with data envelopment analysis (DEA), to understand cost-efficiency in the banking sector of Bangladesh. Their analysis revealed the positive impact of financial deregulation on bank costs. They also found that banks’ efficiency could be negatively affected by directors with political connections. Uddin et al. (Reference Uddin, Shahbaz, Arouri and Teulon2014) dealt with the wider issue of development and tried to link financial development with performance in poverty reduction and economic growth for Bangladesh in the period 1975–2011. Their Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model, with structural break, established the presence of a long-run relationship among the relevant variables.

III Banking Sector in Bangladesh: Performance and Challenges

A Structure of the Banking Sector

After its independence in 1971, Bangladesh, as part of its socialist economic strategy, nationalised all banks except a few foreign-owned ones. Following this step, the banking sector did not experience any significant changes until the beginning of the 1980s, when, under the Structural Adjustment Program, the Government liberalised the banking sector and allowed the operation of private banks. Although the speed of privatisation of the banking sector was quite slow during the 1980s and 1990s, there was indeed significant expansion of the branches of NCBs. Privatisation of a few NCBs, and later sanctioning of privately owned commercial banks, which has accelerated over the most recent decades, have resulted in the current operation of 42 domestic private commercial banks (PCBs) in Bangladesh.

Although the number of banks did not change drastically until 2013, the percentage share of PCBs in total industry assets increased quite remarkably. While in 2001, the share of PCBs in total industry assets was around 35%, by 2017 it had increased to 67%.Footnote 9 Such an increase in the share of industry assets is not a conundrum as PCBs’ share of deposits in the industry also increased over the same period of time. Therefore, in terms of the structure of banks, PCBs can be considered the dominant type of banks, in terms of the aforementioned important indicators.

B Performance of the Banking Sector

This sub-section provides an overview of the performance of the banking sector of Bangladesh in terms of access, stability, efficiency, and depth. An analysis over time, and comparisons with a few comparable countries, is carried out based on the available data.

Table 5.1 summarises the performance of the banking sector of Bangladesh when all types of banks – that is NCBs, DFIs, PCBs, and FCBs – are taken together, according to some standard ratios describing various aspects of banking activity. Ratios are reported for a few points of time over the last 20 years or so, or when they were available. For the most recent year, they are compared to their value in other Asian countries or to averages over groups of countries at the same level of income (least developed countries) or at a higher level (upper middle-income countries (UMICs)).

Table 5.1 Performance of the banking sector

| 1996 | 2001 | 2004 | 2010 | Most recent year after 2016 | Comparator countries, most recent year after 2016 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | Sri Lanka | Thailand | LDCs | UMICs | ||||||

| Access | ||||||||||

| Account holders/1,000 adultsFootnote 1 | 248 | 715 | 726 | 1271 | ||||||

| Bank branches/0.1 million peopleFootnote 2 | 6.9 | 8.6 | 14.7 | 11.9 | ||||||

| Stability | ||||||||||

| Liquidity ratioFootnote 3 | 11.7 | 9.71 | 11.8 | 19.2 | 21.2 | |||||

| Capital adequacy ratioFootnote 4 | 6.9 | 4.7 | 7.5 | 8.7 | 10.8 | |||||

| NPL ratio | 31.5 | 31.5 | 17.6 | 7.3 | 11 | 9.5 | 3.4 | 3.1 | ||

| z-score | 11.1 | 5.8 | 9.5 | 6.7 | 15.9 | 14.1 | 7.9 | |||

| Efficiency | ||||||||||

| ROAFootnote 5 | 7.02 | 2.7 | 4.7 | 1.4 | –0.2 | 2.1 | 1.5 | |||

| Returns on equity (ROE)Footnote 6 | 97.1 | 42.7 | 54.3 | 18 | –2.5 | 24.6 | 11.5 | |||

| Bank cost to income ratioFootnote 7 | 26.7 | 33.1 | 37.4 | 50.3 | 50.8 | 54.5 | 43.7 | |||

| Depth | ||||||||||

| Bank credit/ GDPFootnote 8 | 18.9 | 23.9 | 40.8 | 46.8 | 50.1 | 49.5 | 112.5 | |||

1 Based on the available data from www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/bank_accounts/. Country comparison is also made based on the available data for comparable countries.

3 The ratio of bank liquid reserves to bank assets is the ratio of domestic currency holdings and deposits with the monetary authorities to claims on other governments, non-financial public enterprises, the private sector, and other banking institutions.

4 The capital adequacy ratio or bank capital to assets ratio is the ratio of bank capital and reserves to total assets. Capital and reserves include funds contributed by owners, retained earnings, general and special reserves, provisions, and valuation adjustments. Capital includes Tier 1 capital (paid-up shares and common stock), which is a common feature in all countries’ banking systems, and total regulatory capital, which includes several specified types of subordinated debt instruments that need not be repaid if the funds are required to maintain minimum capital levels (these comprise Tier 2 and Tier 3 capital). Total assets include all non-financial and financial assets.

5 ROA is a profitability ratio that indicates how much profit a company is able to generate from its assets. In other words, ROA measures how efficient a company’s management is in generating earnings from the economic resources or assets on its balance sheet. ROA is shown as a percentage: the higher the number, the more efficient a company’s management is at managing its balance sheet to generate profits.

6 ROE is a measure of financial performance calculated by dividing net income by shareholders’ equity. Because shareholders’ equity is equal to a company’s assets minus its debt, ROE can be thought of as the return on net assets.

7 Operating expenses of a bank as a share of the sum of net interest revenue and other operating income (see www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/bank_cost_to_income/).

8 Domestic credit to private sector by banks refers to financial resources provided to the private sector by other depository corporations (deposit-taking corporations except central banks), such as through loans, purchases of non-equity securities, and trade credits and other accounts receivable that establish a claim for repayment (see www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/Bank_credit_to_the_private_sector/).

Looking first at these indicators over time, two opposite evolutions can be observed. On the one hand, accessibility of the banking system to the public has very much increased over the last 15 years, whether in terms of account holders or bank branches. On the other hand, stability and efficiency indicators overall suggest a deterioration over time, except the NPL ratio between 1996 and 2010, an evolution that is discussed in more detail in the next section. On stability, if the liquidity ratio has not changed much, the recent drop in the capital adequacy ratio is worrying as it suggests that the Bangladeshi banking sector would have more difficulty confronting an economic or financial crisis today than was the case in 2010. However, the evolution of the z-score suggests that the probability of the whole banking system defaulting remains low and is even decreasing. On the side of efficiency, however, all indicators show a worsening of the overall performance of Bangladesh’s banking system. Over the recent past, it is possible that this deterioration may be due to a drop in the interest rate, as has been observed in most countries in the world.

A final indicator, which is more macroeconomic in nature, appears in Table 5.1. It is the depth of the financial system, as measured by the ratio of total bank credit to GDP. It is generally the case that economic development goes hand in hand with financial development. This is clearly confirmed in the case of Bangladesh.

Comparing Bangladesh to other countries is made difficult because indicators are not always available for countries at levels of development similar to or just above Bangladesh. Three countries appear in Table 5.1: India and Sri Lanka in South Asia, and Thailand in Southeast Asia. For liquidity, the comparison is also made for the average LDC or UMIC.

If the comparison is unfavourable to Bangladesh for access – when the benchmark is Thailand – and for the liquidity of banks, the results are more ambiguous for the other indicators. The performance of the Indian banking sector in particular does not look better than Bangladesh’s, even with respect to the NPL ratio. It should be emphasised, however, that the inter-comparability of some of these indicators is not granted. For instance, it is well known that the definition of NPL may vary across countries. More important, standard banking indicators are essentially business oriented and may not be good descriptors of the actual economic performance of the banking sector: that is, its contribution to the good functioning of the economy.

The preceding remark applies particularly to the depth indicator in Table 5.1. Bank credit is of a comparable size in Bangladesh as in India or Sri Lanka, but much less than half of what it is in Thailand, which, admittedly, is at a more advanced level of development. Yet, it must be kept in mind that even if two economies extend the same relative volume of bank credit, the overall economic impact of bank lending may be quite different. The quality of loans and their allocation within the economy are of utmost importance. As a matter of fact, it will be seen below that, despite average indicators that are not unduly unfavourable, some aspects of the banking system in Bangladesh are deeply dysfunctional.

A word must be said about the fact that the preceding indicators correspond to very different situations depending on the type of bank that is being considered. Without getting into details, the major difference appears between PCBs and FCBs, with the latter generally performing better than their domestic counterpart, and between private and public commercial banks (and DFIs), with the latter showing a much higher volume of NPLs and a lower capital adequacy ratio than the former.

C Trend in NPLs

NPLs are loans that do not earn any interest income for a certain period of time, and, more importantly, for which there is a lower likelihood of recovery. NPLs are considered to be one of the critical indicators for banks’ financial stability, as well as profitability, and high NPLs can seriously affect banks’ ability to sustain their operation, including the expansion of credit.

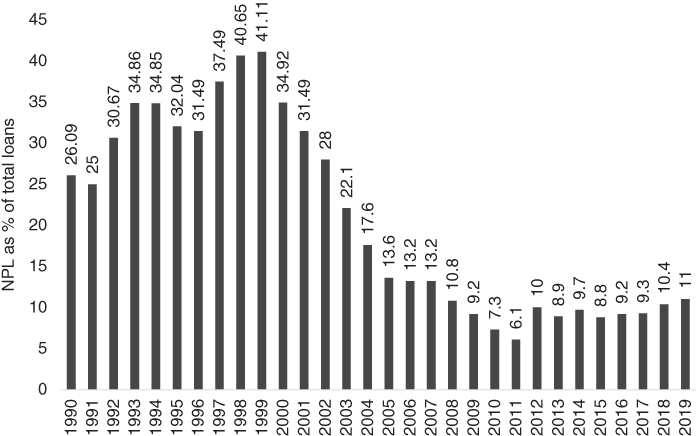

High NPLs are historically considered to be a matter of concern for many Bangladeshi banks and, as shown in Figure 5.1, till the late 1990s the proportion of NPLs was alarmingly high, due mainly to high NPLs of NCBs. Since the late 1990s, with a number of regulatory measures in operation, for the NCBs as well as for many of the PCBs, we observe an immediate decline of NPLs to total loan portfolio. However, that trend has been reversed in recent years as the percentage of NPLs to total loans rose to almost 11% by the end of 2019. Whether considering provisions or not, for all four types of banks, sizeable NPLs are observed. In the case of PCBs, although net NPLs on average are quite low, while analysing the loan profile of PCBs we should keep in mind that most of the NPLs in PCBs are held by a few banks, therefore, the average NPLs of PCBs may fail to capture the depth of the issue.

Figure 5.1 Trend of NPLs as percentage of total loans.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) data show that in September 2019, NPLs as a percentage of the total loans of the banking sector was as high as 12%: the ratios for NCBs and PCBs were around 31.5% and 7.4%, respectively (IMF, 2020). It is therefore evident that, despite the success in reducing the NPLs of NCBs during the 1990s, the problem has returned in recent years. Unlike the 1980s and 1990s, NPLs have turned out to be a problem of PCBs as well, which necessitates further analysis of the issue from a political economy point of view.

A close examination of sector-wise distribution of NPLs reflects that trade and commercial sectors constitute more than 28% of total NPLs in 2018.Footnote 10 The RMG sector alone is found to account for more than 12% of the NPLs (and, in fact, around 27% of the NPLs in the manufacturing sector), followed by other large-scale industries (7.63%). This distributional pattern of NPLs is, however, consistent with the distributional pattern of sector-wise shares of loans. This highlights that important sectors of the economy constitute a significant proportion of NPLs and that weak institutional discipline of the banking sector has also ‘helped’ these sectors to grow.

D Trend in Interest Rates

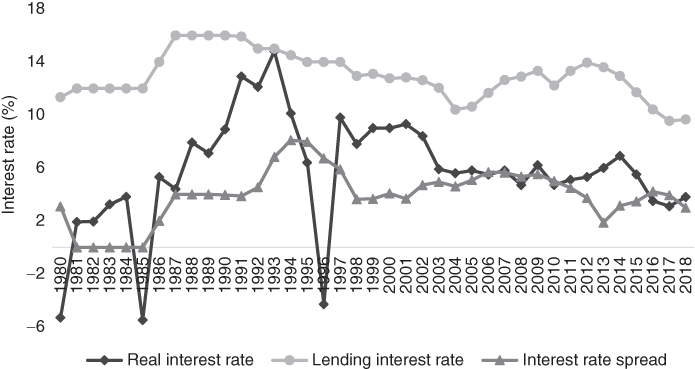

Figure 5.2 presents the trend in the lending interest rateFootnote 11 and real interest rateFootnote 12 in Bangladesh between 1980 and 2018. In 2018, the interest rate spread in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Thailand was 3%, 2.7%, 1.8%, and 2.9%, respectively. This suggests that the interest rate spread in Bangladesh is not very different from that of other developing countries.

Figure 5.2 Trend in the lending interest rate, interest rate spread, and real interest rate.

The real interest rate affects financial sector development through its influence on the volume of financial savings and on the cost of capital (McKinnon, Reference McKinnon1973; Shaw, Reference Shaw1973; Fry, Reference Fry1988; Leite and Sundararajan, Reference Leite and Sundararajan1990). As depicted in Figure 5.2, negative or very low interest rates in Bangladesh in the 1980s corresponded typically to a repressed financial system where credit is rationed and allocated in some authoritarian way, or as the result of ‘deals’ among sectors or firms – which is discussed later in this chapter. The two troughs, in 1985 and 1996, were due to inflation surges. After liberalisation of the financial market and a surge in the real rate, due to decelerating inflation with a lending rate still under control, the real rate followed the same declining trend as the nominal rate, because inflation was stabilised – after the accident of 1996. The declining trend of the lending rate also followed an international trend that started in the early 2000s but accelerated after 2008 – for example the declining trend in the yield on US 10-year bonds or on the German Bund.

It may also be noted in Figure 5.2 that the real deposit rate, which corresponds to the gap between the real rate and the interest spread,Footnote 13 has tended towards zero in the recent period. It was high, around 3% on average, throughout the 1990s, shrank in the mid-2000s, and has fluctuated around zero since then.

In 2018, the average real interest rate for Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Thailand was 3.8%, 5.1%, 6.9%, 4.1%, and 2.7%, respectively. The Bangladesh real interest rate was thus in the lower half of the range defined by these Asian countries.

Despite repeated instructions from the Government (even exhortations by the current, powerful prime minister) to maintain an interest rate spread within 3%, with a 6% deposit rate and 9% lending rate, the banking sector has failed to maintain such a provision.Footnote 14 However, following the strict instructions of the Finance Minister to reduce the lending rate to 9% from 1 April 2020, bankers decided not to offer a deposit rate over 6%.Footnote 15 However, this announcement has led to concern as deposit interest rates have dropped close to the inflation rate,Footnote 16 and also this may decrease banks’ profitability (Hasan, Reference Hasan2020).

E Efficiency of Banks in Bangladesh

The trend and pattern of key economic indicators of the banking sector reveal that the performance of the sector as a whole is not satisfactory, and, except for FCBs, neither NCBs nor PCBs can be considered to have exhibited satisfactory performance in terms of relevant indicators. In this section, we attempt to understand whether the chosen banks (PCBs and FCBs) are performing ‘optimally’ with regard to their assets, income, expenses, and other chosen indicators and to understand the factors behind the ‘sub-optimal’ performance (if any) of certain banks as opposed to others. In this context, from a methodological point of view, we used the DEA,Footnote 17 a statistical tool that is often used to assess the relative efficiency of firms (see Mercan et al., Reference Mercan, Reisman, Yolalan and Emel2003; Debnath and Shankar, Reference Debnath and Shankar2008). In addition, in order to understand the factors behind the relative efficiency of banks, we estimated a panel logit model where we used the efficiency score with other banking sector indicators: most importantly, the components of the CAMELSFootnote 18 rating.

In the analysis of the efficiency of the private banking sector of Bangladesh, we have used the input-orientedFootnote 19 DEA analysis using the CCRFootnote 20 and BCCFootnote 21 models to measure overall technical efficiency (OTE) and pure technical efficiency (PTE), respectively. In the context of the banking sector of Bangladesh, we adopted the intermediation approach for selecting input and output variables, which considers banks as financial intermediaries where banks produce services through the collection of deposits and other liabilities and their application in interest-earning. In this analysis, as input variables we have chosen: (i) total assets; (ii) number of employees; and (iii) sum of deposits and borrowings. As output variables we have included: (i) net interest income; (ii) non-interest income; and (iii) NPLs. Apart from the traditional variables used for the intermediation approach, we have the NPLs variable as a (negative) output variable.Footnote 22 In addition, all the input and output variables except labour are measured in Bangladeshi Taka (BDT) in millions, and we have conducted the analysis from 2015 to 2018, on 44 national and foreign PCBs.

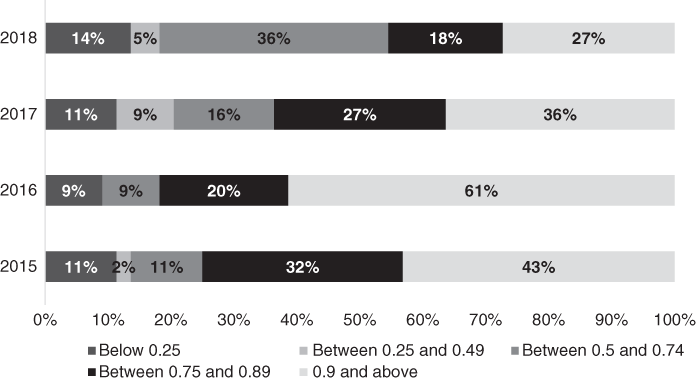

Figure 5.3 presents the distribution of the efficiency scores of the banks calculated using the DEA. It is clear that over the years, the percentage share of banks with an efficiency score of 0.9 and above has declined and the percentage shares of very poorly performing banks (efficiency score below 0.25), poorly performing banks (efficiency scores between 0.25 and 0.49), and moderately performing banks (efficiency scores between 0.5 and 0.74) have increased. In 2018, 55% of the banks had efficiency scores below 0.75. In contrast, only 25% of the banks in 2015 had efficiency scores below 0.75. Most of these low-performing banks are PCBs.

Figure 5.3 Distribution of the efficiency score of private banks by year.

Note: Total number of private banks = 44.

F Development Implications of the Status of the Banking Sector in Bangladesh

The linkage between economic development and the banking sector can be multi-faced and often the indirect linkage can be quite strong too. One of the most important ways in which the banking sector might have an impact on the growth and economic development of a country is through channelling the savings of depositors for the purposes of investment. Despite a persistent high growth rate in Bangladesh for the last decade or so, there has not been much progress in terms of private investment as the ratio of private investment to GDP has remained almost stagnant in recent years. There are concerns that poor governance in the banking sector, including the high amount of NPLs, has restricted banks’ capacity to maintain a narrow interest rate spread and to reduce the lending rate to borrowers. Such a high cost of borrowing and access to finance is generally considered to be one of the key challenges for entrepreneurs in expanding their businesses (see International Finance Corporation (IFC), 2020).Footnote 23

One important area of concern is that the Government’s borrowing from the banking sector has been on an increasing trend over the past few years, which has also been accompanied by an accelerated selling of National Savings certificates (i.e. ‘government bonds’). In FY18, the Government’s borrowing from the banking system increased to as high as BDT 1780.9 billion (around US$ 21.34 billion) – equivalent to 8% of GDP. The increase in the Government’s borrowing from the banking sector risks crowding out credit to the private sector (Rana and Wahid, Reference Rana and Wahid2016; see also the discussion in Chapter 2 of this volume).

It is also important to mention that since the 1980s, the Government has been allocating a significant amount in the annual national budget to subsidising the ailing banking sector, to cover the losses of these banks.Footnote 24 After the initiatives to privatise NCBs in the 1990s, a falling trend was observed in the recapitalisation of banks (NCBs) by the Government; this trend has been reversed in recent years. In FY14, there was a massive surge in the recapitalisation process, which, although it has declined in subsequent years, still since FY17 has been annually as high as BDT 10 billion (around US$ 0.12 billion). The national budget for FY20 allocated BDT 15 billion (around US$ 0.18 billion, equivalent to 0.75% of GDP) to the recapitalisation of NCBs. It is not only the direct monetary expense which is at stake here, this recapitalisation expenditure should also be understood from the viewpoint of opportunity costs to the society. With Government education expenditure being around 2% of GDP and health expenditure less than 0.5% of GDP, and also with a very low tax–GDP ratio of around 9%, the consequence of this massive recapitalisation for development cannot be ignored. The ‘costs’ of poor governance in the banking sector is therefore multi-dimensional and can have long-term implications for the Government’s development initiatives.

In addition to the apparently ‘visible’ macro and fiscal indicators, it is often argued that poor governance of the banking sector is having negative consequences through a number of indirect channels. According to a Washington-based think tank, Global Financial Integrity, the total value gap identified in trade between Bangladesh and all of its trading partners in 2015 was US$ 11.5 billion, which was 19.4% of total trade (Global Financial Integrity, 2020). The gap is between the value of exports reported by Bangladesh exporters and the value of imports reported by importers in importing countries. This estimate puts Bangladesh among the top 30 countries of the world in terms of such trade mis-invoicing data, and third among Asian countries, after Malaysia and India. Though not conclusive, this mis-invoicing is argued to be linked to capital flight from the banking system in the form of NPLs (see Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2019; Haider, Reference Haider2019).

IV Politics of the Banking Sector: A Brief History

The first Awami League regime (1972–1975) instituted a ‘socialistic’ economy whereby banks were nationalised. The authoritarian and later dominant party rule (see Hassan and Raihan, Reference Hassan, Raihan, Pritchett, Sen and Werker2018 for a definition and analysis of dominant party rule) of General Ziaur Rahman–the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (1975–1981) dismantled the ‘socialistic’ system of the previous regime and pursued a market-led economic strategy, but banks remained in the public sector. This period witnessed the rise of state-sponsored capitalism that relied heavily on an aggressive and very liberal industrial loan sanctioning policy for the development of private industries. Regulatory weaknesses, bank officials’ corruption and collusion (with private entrepreneurs), and the regime’s priority to distribute political patronage led to the beginning of the ‘loan default culture’ (see Sobhan and Mahmood, Reference Sobhan and Mahmood1981; Hassan, Reference Hassan2001; Islam and Siddique, Reference Islam and Siddique2010 for case studies of loan defaults. Box 5.1 presents two such cases). The loan sanctioning regime during this period can be characterised as based on largely open deals. Closed deals did exist, but marginally.Footnote 25

Box 5.1 Two examples of loan defaults in the 1990s

Case Study 1: XYZ Private Limited Company

During early 1990s, XYZ (not its real name) company was owned by close relatives of one of the highest-level political leaders in the country. The company was sanctioned BDT 131.4 million (around US$ 3.32 million) by Sonali Bank, a leading NCB. The bank approved a ratio of debt and equity at 70:30, that is 30% of the total investment would be provided by the borrowing company, which was actually provided through bridge financing by another NCB, Uttara Bank. Interestingly, the company pledged the same property as collateral to Uttara Bank that had already been pledged to Sonali Bank, a typical fraudulent practice. According to the conditions specified in the loan agreement, the borrowing company was supposed to deposit to the bank BDT 38 million (around US$ 0.96 million), as part of the equity for financing construction (factory building) and the purchase of industrial machines, but due to special ‘appeal’, the board of directors of the bank permitted the borrower to finance the construction and purchase from their own sources. At the borrower’s ‘request’, the bank either relaxed or simply did not enforce various terms and conditions and standard policies related to term lending. For example, the required cash margin to be deposited was lowered from BDT 23.2 million to BDT 10 million (from US$ 0.59 million to 0.25 million); insurance requirements regarding the project in general, and imported machines in particular, were relaxed to provide special benefits to the borrower; special payments by the bank were made to cover the deficit in equity.

In the tender process (for importing machines), the bank authority rejected the firm which quoted the lowest price and approved the one which was selected by the borrowing company. Changes in all of these policies and conditions were made on a top-priority basis by the board of directors of the bank. Instead of the minimum requirement of a 90-day duration of a sanctioning project (as determined by the government), this particular project was sanctioned in 74 days. XYZ was registered as an export-oriented industry for which it received substantial duty exemptions, but the company actually produced only for the local market. Commenting on the loan repayment behaviour of the company, the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report observed, ‘Although the company is running in full scale, so far the owners have not shown any interest in repaying its bank loans’.

Case Study 2: Bangladesh Match Company

The owner of the company was Ispahani Group, one of the oldest business groups in Bangladesh. The company had been experiencing huge losses and personnel were laid off in 1990. At that time, it owed Rupali Bank (an NCB) BDT 40 million (around US$ 1.16 million). In 1991, the owner decided to close down the company and an arrangement was made with Rupali Bank to pay off the debt in instalments. However, after the 1991 parliamentary election, the Speaker of the fifth parliament wrote a letter to the chairperson of Rupali Bank advising him not to implement the decision to close down the activities or sell them to a third party without receiving clearance from the prime minister. The Speaker apparently intervened on behalf of the trade unions of the particular industry. In 1992, the Speaker wrote another letter to the chairperson of the bank informing him about the prime minister’s decision to re-open the industry. The Speaker also advised the bank authority to provide sufficient funds and other assistance deemed necessary to the owner of the industry. The bank management eventually decided to postpone the decision to close down the industry and also to provide BDT 10 million (around US$ 0.26 million) as cash credit. Although the owner continued to default on the total loan (approximately BDT 66.6 million equivalent to US$ 1.66 million by 1994), the bank authority increased the cash credit limit to BDT 15 million (around US$ 0.37 million). This was done by the direct intervention of the Speaker. In 1995, the owner was actually paid more than the authorised limit (BST 17.5 million equivalent to US$ 0.43 million). Since then, the overdue loan of Bangladesh Match Company continued to accumulate and as at 1998 the amount due was approximately BST 80.5 million (around US$ 1.72 million).

The authoritarian regime of General Ershad (Jatiya Party, 1981–1990) nurtured a ‘robust’ form of crony capitalism through a loan sanctioning process that was largely based on closed deals, in contrast to the previous regime (Hassan, Reference Hassan2001; Hassan and Raihan, Reference Hassan, Raihan, Pritchett, Sen and Werker2018; see Kochanek, Reference Kochanek2003 for evidence on the rampant crony capitalist practices of the Ershad regime). The regime saw an increasing trend of NPLs and further consolidation of the default culture. Yet such a liberal and aggressive loan sanctioning process (with all the features of mal-governance mentioned above) contributed to significant development of industrial entrepreneurship in the country, particularly in the RMG sector. The critical factor here was the continuation of open deals in terms of accessing loans by the private sector. The period also witnessed trade union-centred militant politics related to de-nationalisation of the banks, and an increasing and aggressive stance of civil society and the media towards the default culture and its consequences (Monem, Reference Monem2008; Hassan, Reference Hassan2001).

In terms of the policy regime of the banking sector, the period before 1990 can be broadly considered as one of financial repression (see Raquib, Reference Raquib1999 for an analysis of the policy of financial repression followed by different regimes during the pre-1990 decades). This refers to a bundle of government policies characterised by low real interest rates (see Figure 5.2), with the aim of generating cheap funding for government spending. Also, as low or negative real rates generate excess demand, rationing took place. Some sectors were favoured in the rationing scheme: for instance, state-owned companies, at the expense of the private sector. The objective of successive regimes during this period was to supply cheap money to state-owned enterprises and other priority sectors. Given this broader policy objective, the regimes initiated a banking sector reform during 1980–1990, eschewing reforming the broader policy (financial repression)Footnote 26 and rather focusing on the policy of promoting the licensing of PCBs and the de-nationalisation of NCBs (three NCBs were privatised in 1983/1984 and four PCBs were granted licences to operate in the early 1980s). The reform agenda during this period essentially reflected the existing elite political settlement/equilibrium among political elites and the burgeoning business class, and influential Western donors (led by the IMF, especially in the domains of privatisation, and fiscal and banking sector reform). Such a political settlement effectively excluded organised labour and white collar staff in the public sector, including NCBs. The latter actors resisted the de-nationalisation of banks, as alluded to earlier, but without any success, indicating the robustness of the elite political settlement. The de-nationalisation of the banks and licensing of PCBs also indicated the IMF’s and World Bank’s clout over economic policy decisions during the 1980s, when the country was still largely dependent on external aid or support to finance its development expenditures (see Sobhan, Reference Sobhan1991; Chowdhury, Reference Chowdhury2000).

The ‘competitive democratic’ phaseFootnote 27 saw a further deepening of the default culture (with some fluctuations). The default culture was rampant during the 1990s, saw some improvements during the 2000s, and then again showed a growing trend during the 2010s. The period also witnessed the rise of private sector banksFootnote 28 (numerically as well as a powerful corporate actor), a crisis within private sector banks (weak corporate governance, insiders lending, etc.), and the Government’s attempts to rescue problem banks. Also, a significant development during this period was the deeper involvement of the World Bank in prodding the Government to initiate a comprehensive banking sector reform (that eventually led to the establishment of a Commission in 1997). Though the Banking Companies Act (BCA) 1997 was first enacted in 1991Footnote 29 as part of the Financial Sector Reform Project (FSRP), one of the core demands of the World Bank was the amendment of this act to bring the prevailing standard of prudential and supervisory regulations up to a par with the Basel Committee guidelines. Due to the World Bank’s sustained pressure, the act was finally amended in 1997.

The late 1990s saw a subsequent de facto decline in the power/autonomy of the central bank. Also, there was the emergence of a private sector banking association (Bankers Association of Bangladesh (BAB))Footnote 30 as a powerful actor, leading to its ability to capture policies and especially regulatory policies related to banks – a phenomenon termed state capture in the political economy literature. BAB and other prominent business associations successfully lobbied the political authorities to relax, and in some cases completely reverse, the stricter provisions in the BCA (see Box 5.2).

Box 5.2 State capture by the BAB in the late 1990s

The Government’s decisions to standardise rules and regulations for better enforcement of credit discipline evoked strong opposition from influential sections of the business community. Opposition intensified in 1997, when the central bank started implementing new credit regulations and, as a consequence, many big business groups were denied loans. The private sector found the BCA (amended in 1997) detrimental to their interests. Immediately after the amendment of the act, the BAB and other prominent business associations (mainly the Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industries (FBCCI)) started a systematic campaign to further amend or simply do away with some of the stricter rules and regulations. Organised business successfully lobbied the political authorities to relax and in some cases completely reverse the stricter provisions in the BCA (prudential regulations in the loan repayment process). In other cases (the central bank’s supervision over PCBs’ internal management), new provisions remained intact, as formal mandatory laws in the book, but were largely ignored in practice by the market actors. Non-compliance with the rules was possible due to collusive linkages of these actors with the supervisory authorities (bureaucratic or political), at the highest levels of the hierarchy.

During 1990–2000, the competitive democratic phase emphasised market-oriented liberalisation, doing away with or limiting the policies of financial repression of the previous decades, and encouraged more private sector participation in the banking sector (Institute of Governance Studies (IGS), 2011). As part of the first objective, the core reform strategies, formulated and implemented under the World Bank–designed FSRP (initiated during the early 1990s), included, among other things, the gradual deregulation of the interest rate structure, and providing market-oriented incentives for priority sector lending. To realise the second objective, a large number of PCBs were given licences. The major beneficiary of the priority sector lending was the RMG sector.Footnote 31 The predominantly market incentive–based reform, though it led to the development of a wide range of financial products and services (merchant and investment banking, small and medium-sized enterprise and retail banking, credit card and offshore banking, etc.), failed to tackle some key banking sector problems, such as high ratio of NPLs in both NCBs and PCBs and weak enforcement of capital adequacy and other regulatory policies. Also, in dealing with the policies of financial repression, as mentioned before, the reform ended up with credit rationing, and eventually a deteriorating level of credit allocation. For instance, the flow of credit declined over the 1990–1999 period to some of the priority sectors, such as agriculture, and small and cottage industries, and a similar decline was also observed in terms of the relative share of the rural banking system (IGS, 2011). In addition, the introduction of the interest rate flexibility failed to create a competitive environment among NCBs and PCBs. The upshot is that the market fundamentalist approach of the FSRP was largely unsuccessful in achieving the desired objectives of the reform programme, since, given its faith in the market per se, it focused heavily on the deregulation dimension and placed less emphasis on the necessity for broadening/deepening prudential regulation aspects (IGS, 2011).

Such lacunae in the regulatory aspects were emphasised by the Bank Reform Committee (BRC), formed after the termination of the FSRP in 1996, which submitted its recommendations in 1999. The BRC blamed supervisory and regulatory forbearance as one of the core issues behind the problems of the banking sector. The phase of reform initiated during the early 2000s essentially premised its policy prescriptions on these issues identified by the BRC and emphasised risk-based regulations and strengthening of the central bank’s capacity (both supervisory and technical infrastructure-related) to address the banking sector problems. The Central Bank Strengthening Project, initiated in 2003 (part of the stabilisation programme signed with the IMF for 2003–2006), included strengthening of the legal framework, increased research capacity, capacity building in relation to supervisory and prudential regulations, auditing, and the development of automation-related technology. In terms of addressing the default culture, a series of new laws, regulations, and instruments were enacted. To create a competitive environment for the private sector banking strategy, a staged withdrawal of public ownership from the sector was initiated that involves divestment and corporatisation of substantial shareholdings of three publicly owned banks. Increased private sector participation in the sector continued throughout this phase, with licensing of a dozen PCBs. The reform still failed to achieve what it intended to, due to constraints of meta-level political and governance issues (cronyism, de facto political control of the regulatory authority, a political–business elite collusive nexus, etc.). In the beginning of the 2000s, important improvement was noted in terms reduction in NPLs and the NPL ratio stabilised at an order of magnitude below the 40% level reached in the late 1990s. But this trend fizzled out at the end of that decade, and the NPL ratio started to increase from the beginning of the 2010s. The licensing of the PCBs became largely a political patronage distribution mechanism, and ownership predominantly went to individuals with partisan political identities. Many new PCBs came into being despite the central bank’s objections based on an economic rationale (the market saturation of banks being one issue).Footnote 32

Bangladesh’s current regime (2014–) can be termed one of ‘dominant party rule’. This period has seen an acceleration of NPLs and further marginalisation of the central bank (de facto weakening of its authority). Other relevant features of this period are a continuation of the licensing of private banks based on political considerations, deteriorating governance status of the banking sector, further increases in the capture of the state/central bank by private banks – both individually and collectively (associations) – resulting in regulatory capture (laws, rules, loan classification criteria, etc.), entrenchment of crony capitalistic practices by private bank owners, and the emergence of banking sector oligarchies.

The Finance Ministry’s overreach in licensing private banks, under political considerations, without the recommendation of the Bangladesh Bank, not complying with the suggestions of the central bank and influencing the decisions of the autonomous central bank, are a few of the manifestations of policy and regulatory capture and political patronage in the sector.Footnote 33 Though it is an independent regulatory authority, the central bank is unable to completely monitor these banks as they are largely owned by politically influential people.Footnote 34 Some of these banks have been linked to loan scams, aggressive lending, and violations of banking regulations, among other issues, which tends to pose serious threats to the banking sector, according to the central bank’s own assessment.Footnote 35 Table 5.2 presents a summary of the scams in the banking sector in Bangladesh in recent years.

Table 5.2 Scams in the banking sector in Bangladesh in recent years

| Banks | Key irregularity | Measures taken |

|---|---|---|

| Sonali, Janata, NCC, Dhaka, Mercantile Bank (2008–2011) | BDT 40.89 million (approximately US$ 0.58 million) bank loan with forged land documents (Dhaka Tribune, 28 August 2013) | On 1 August 2013, Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) filed cases against Sonali Bank, Fahim Attire, and certain individuals; BDT 10 million (US$ 0.13 million) was given back to Sonali Bank (Dhaka Tribune, 2 August 2013; New Age, 2 August 2013; The Daily Star, 2 August 2013) |

| Basic Bank (2009–2013) | BDT 45,000 million (approximately US$ 604 million) with dubious accounts and companies (The Daily Star, 28 June 2013) | In September 2015, ACC filed 56 cases against 120 people (New Age, 13 August 2018) |

| Sonali Bank (2010–2012) | BDT 35,470 million (approximately US$ 472 million) embezzled by Hall Mark and other businesses (The Daily Star, 14 August 2012) | In October 2012, ACC filed 11 cases against 27 people (Dhaka Tribune, 11 July, 2018) |

| Janata Bank (2010–2015) | BDT 100,000 million (approximately US$ 1.3 billion) appropriated by Crescent and AnonTex (Dhaka Tribune, 3 November 2018) | On 30 October 2018, the Enquiry Committee of Bangladesh Bank submitted a report (Dhaka Tribune, 3 November 2018) |

| Janata Bank, Prime Bank, Jamuna Bank, Shahjalal Islami Bank, Premier Bank (June 2011–July 2012) | BDT 11,750 million (approximately US$ 151 million) by Bismillah group and associates. (The Daily Star, 7 October 2016) | On 3 November 2013, ACC filed 12 cases against 54 people (The Independent, 11 September 2018) |

| AB Bank (2013–2014) | BDT 1,650 million (approximately US$ 21.2 million) (The Daily Star, 12 June 2018) | On 25 January 2018, ACC filed a case against the former chairman and officials of AB Bank (The Daily Star, 12 March 2018) |

| NRB Commercial Bank (2013–2016) | BDT 7,010 million (approximately US$ 90 million) of loan (New Age, 10 December 2017) | On 29 December 2016, the Bangladesh Bank appointed an observer to check irregularities (Dhaka Tribune, 7 December 2017) |

| Banks | Key irregularity | Measures taken |

| Janata Bank (2013–2016) | BDT 12,300 million (approximately US$ 158 million) of loan scam (The New Nation, 22 October 2018) | In October 2018, Thermax requested to reschedule the loan and Janata Bank’s board endorsed it and sent it to the Bangladesh Bank (The Daily Star, 21 October 2018) |

| Farmers Bank (2013–2017) | BDT 5,000 million (approximately US$ 63.7 million) of fund appropriation by 11 companies (The Daily Star, 24 March 2018) | On January 2018, the Bangladesh Bank directed that an audit be conducted. In April 2018, ACC arrested four accused persons (The Independent, 11 April 2018) |

| Bangladesh Bank (5 February 2016) | BDT 6,796 million (approximately US$ 86.6 million) by international cyber hacking from the treasury account of Bangladesh Bank (The Daily Star, 5 August 2017) | On 19 March 2016, the Government formed a three-member investigation committee (The Daily Star, 5 August 2017) |

Historically, there have been many regulations covering the banking sector, especially regarding the entry/exit mechanism of banks and their governing bodies. The BCA has been amended six times since its formation. Recent regulations tend to be strategically done to bolster political control over the governance of these banks, so they can be used to distribute patronages among loyal political elites. These new laws have made changes in directorship positions, triggering a state of confusion among depositors and other stakeholders.Footnote 36

V An Analytical Narrative of the Governance Failures in the Banking Sector

The governance crisis in the banking sector in Bangladesh is not manifested in frequent collapse of banks but in the serious insolvency of some banks. However, these insolvent banks are typically protected from market competition and not allowed to go bankrupt by recapitalising them through government subsidies. During the last few decades, only one bank has collapsed in Bangladesh.Footnote 37 The banking system in Bangladesh is a classic example of what has been known in the banking literature as ‘the walking dead bank syndrome’, characterised by insolvency and undercapitalisation of an important segment of the system (Burki and Perry, Reference Burki and Perry1998). The implications of such government subsidies and other forms of insurance policies are profound in terms of banking sector governance. Such policies also have serious effects on the incentives of the bank management and depositors to demand governance reforms in the banking system.

A Central Bank

Bangladesh Bank, that is the central bank of Bangladesh, tends to be a very weak institution. Due to various formal and informal controls, it actually enjoys only a marginal degree of policy and operational independence. It is de facto subservient to the MOF even in regard to some of the core functions of the central bank, such as regular banking supervision. However, it is not only the formal power that has reduced the independence of the central bank. Governments also tend to act beyond their legal mandates. For instance, existing rules clearly prohibit appointing the Governor or Deputy Governor of the central bank from the government bureaucracy. But these rules have never deterred successive governments (authoritarian and democratic) from appointing members of the civil service to such positions on an ad hoc basis.Footnote 38 The Government has also effectively marginalised the role of the Bangladesh Bank in the decision-making processes related to operational matters and banking sector governance. Though the BCA 1991 empowered the Bangladesh Bank to regulate the country’s banking sector as an autonomous body, the central bank lost its independence after the MOF established its own banking division. An example of the marginalisation of the Bangladesh Bank can be seen from the following quote of a supernumerary professor at the Bangladesh Institute of Bank Management: ‘A few days ago (in November 2017), the central bank turned down proposals for setting up two new private commercial banks. In response, the ministry instructed them to proceed that would allow parties to get licences to set up private banks. How does such an action leave any room for the bank to operate independently?’Footnote 39

In dealing with critical policy issues, such as monetary policy or lending to the Government, and governance issues – for instance, special monitoring of insolvent banks or problems of NPLs of commercial banks – the tendency of the Government has been to bypass the formal approval process of the central bank.Footnote 40 In fact when it comes to governance issues, the Government seems to be more inclined to limit central bank’s authority. An ex-governor of the Bangladesh Bank mentioned: ‘In Bangladesh, there is a “dual” system of control of the banking sector. The state-owned commercial banks and specialised banks, and some statutory banks are controlled by the Bank and Financial Institution Division of the MOF. On the other hand, all private commercial banks, foreign banks, non-bank financial institutions are regulated by the Bangladesh Bank. This “duality” of control has resulted in uncoordinated, often weak, policy measures for the government regulated banks. Bangladesh Bank has serious limitations in enforcing prudential and management norms in these banks, which have made the whole banking sector weak and vulnerable through “domino effect”.’Footnote 41

B Corporate Governance in the PCBs

Unlike NCBs, PCBs are characterised by reasonably efficient internal management. The bank authorities have successfully avoided the problems that plagued NCBs, since high priority was given to minimising administrative costs. Also, competitive salaries and various other performance-related incentives have contributed to greater management efficiency. However, the central problem with PCBs lies in the area of corporate governance. For a better understanding of the problem, we need to go beyond the conventional perspective of corporate governance, which fails to take into consideration the contingent nature of institutions and the political economy settings. The conventional perspective, developed essentially in the context of the UK and USA (‘Anglo-American model’), assumes the following: the existence of widely held firms (i.e. firms with a fairly large number of dispersed shareholders); firms are subject to effective legal and juridical (civil and criminal) constraints; and firms rely on ‘anonymous finance using primarily arm’s-length contracts and third-party intervention through the market for corporate control’ (Berglof and von Thadden, Reference Berglof, von Thadden, Pleskovic and Stiglitz1999). The defining characteristic of such corporate governance is ‘strong managers, weak owners’ (Roe, Reference Roe1994), and the main governance problem is the conflict between self-interested management and the weak dispersed shareholders.

Such a model of corporate governance cannot explain the realities in the developing world. In the latter context, firms are usually family-owned or closely held (i.e. more or less concentrated ownership), legal and juridical constraints are very weak, and close ties between business interests and government is much more common (‘crony capitalism’), resulting in large-scale corporate fraud and theft. Also, the stock market is less salient as an external source of finance, and firms typically raise funds from sources such as business groups (‘channelling resources between its firms’), family, and friends. In some developing countries like Bangladesh, where the banking sector is characterised by large-scale governance failure, NPLs tend to be another major source for raising funds.Footnote 42

The above features also largely characterise the structure of corporate governance of PCBs in Bangladesh. Concretely, PCBs are closely held firms, that is mainly owned by a few large shareholders,Footnote 43 who have strong control over the managers. In that sense, the defining characteristic of the corporate governance of PCBs is (paraphrasing Roe): strong owners, dependent managers (bank management), and very weak outsiders (i.e. stockholders). Consequently, the main corporate governance problem is that there are hardly any effective self-interested countervailing groups to prevent rampant corporate fraud and theft by the bank owners.

In general, the monitoring and supervision of banks are very complex issues involving serious incentive problems and information asymmetry. For instance, depositors may lack necessary incentives to proactively monitor the performance of banks since they have less costly options of withdrawing their deposits if necessary: that is, depositors may vote with their feet if they find the bank is not viable. The incentive problem also arises due to the presence of deposit insurance. For instance, the Deposit Insurance Fund in Bangladesh has largely contributed to depositors’ complacency (regarding gross inefficiency and insolvency of the banks) and consequently has hindered the free play of market mechanisms in disciplining banks, that is the depositors may have little incentive to vote with their feet. Such complacency seems to be also an outcome of the presence of the Government’s explicit guarantees (bailing out of failing banks) and implicit guarantees (regulatory forbearance).Footnote 44 Moreover, depositors tend to lack sufficient information to make a proper evaluation. But even if they have better information, the policy of deposit insurance would reduce the incentive to use that information. There are also collective action problems that severely limit depositors’ activism. In contrast to the small and concentrated groups with high stakes in the system – for instance, the bank owners – numerous depositors, each having a small stake in the banks, tend to be less motivated and consequently less effective in realising collective objectives. The costly process of information collection and the possibility of other depositors free riding on such information are also strong disincentives facing individual depositors in terms of taking individual initiatives to generate information. The point is this: there are important reasons for depositors to delegate the monitoring and supervision role to specialised agencies that will act on their behalf to mitigate collective action problems and reduce information asymmetry and the transaction costs of monitoring. Two forms of agencies are typically available: the formal regulatory institutions (the central bank, for instance) and varieties of countervailing private actors or ‘reputational agents’Footnote 45 with strong incentives to monitor corporate firms.

In Bangladesh, reputational agents have largely failed to represent depositors’ interest by playing the role of an effective monitor of commercial banks. To begin with, there are very few such agents or institutions in Bangladesh relevant to banking sector corporate governance. For example, credit rating agencies, investment analyst firms, and depositor or stockholders associations have yet to emerge in any significant sense. Organised legal activism tends to focus more on environmental, civil, and human rights issues, rather than financial sector mal-governance. The role of auditing and accounting firms has been very perverse, which in effect reinforces rather than mitigates the information asymmetry between banks and depositors, as well as corporate fraud and other opportunistic behaviour of bank management and owners.Footnote 46 An exception, in this regard, has been the print media. In fact, to the extent that a certain degree of transparency and accountability exists in the system, the credit for this can perhaps largely go to actors like the print media. The print media’s role as monitor has been very critical. Media trial (naming and shaming of defaulters, exposure of banking sector-related corporate fraud, etc.) has probably played a more important role than formal judicial and law enforcement processes in ensuring some degree of discipline in regard to powerful bank owners, defaulters, and cronies.Footnote 47

Discussion with bank officials (current and ex) and academics suggest that auditing and accounting firms in Bangladesh have largely failed to play their role of effective monitors of corporate behaviour of commercial banks.Footnote 48 The problem is not a lack of technical competence (although this is low) but mainly bad governance. Whatever formal regulations exist, in practice the auditing and accounting firms do not seem to be subject to any form of accountability. For instance, no legal actions have ever been taken against any auditors by depositors or shareholders. The central bank has never disciplined or disqualified any auditing firms for sloppy work or violations of rules. Given such a weak accountability structure and legal enforcement, a large section of the auditing profession has been involved in blatant violation of corporate rules and ethics, auditing fraud, and collusive corruption with bank management. For instance, auditors collude with bank management to hide irregularities in the records, change loan classification entries and provision for loan losses to conceal loan defaults, and exaggerate the performance of banks by concealing expenses and showing income from interest generated from defaulted loans.Footnote 49 Another problem is the distorted accountability structure, that is executive authorities’ control over the regulatory agencies. For instance, the central bank does not receive audit reports, instead the MOF does. A collusive nexus is much easier to establish in the executive domain of the state than in the central bank.

The most important public source of external restraint has been the central bank, which has the formal supervisory authority over PCBs.Footnote 50 However, experiences in the last two decades (with some variations) suggest that it has largely failed to control such fraudulent practices. The regulatory failure, on the part of the central bank, needs to be explained by relating the corporate governance problem to the larger political–economy settings.

Licences to set up banks in the private sector have mainly been given to politically favoured cronies, most of whom have also been large loan defaulters. The privatisation of Pubali Bank in 1983 is a typical example of this process. The Bank had an estimated value of BDT 3 billion (around US$ 0.12 billion), but during privatisation, it was deliberately undervalued at BDT 160 million (around US$ 6.5 million). The majority of the new owners were already large defaulters (with the same bank), with one of them defaulting in the amount BDT 10 million (around US$ 0.41 million). These bank owners continued to wield political influence over successive democratic regimes. Discussions with senior bankers and recent scanning of print media suggest that the licensing of banks in the private sector (PCBs) over the last decade has also continued to be largely based on corrupt deals and political patronage. For example, several banks that have received licences in past seven to eight years, such as Farmers Bank, NRB Global Bank, and NRB Commercial Bank, suffered a severe liquidity crisis during the 2016/2017 fiscal year. The problem was particularly acute in the case of Farmers Bank, which had to be bailed out by the Government. Prominent economist Wahiduddin Mahmud noted that repeated violations of bank policies led to Farmers Bank’s current dilapidated state. He stated: ‘The influence of politicians has helped them to establish new banks without extensive scrutiny and obtain huge amounts of loans.’Footnote 51

Given the political clout of the owners of PCBs, and the weak rule of law, the central bank has had very little success in enforcing laws and rules against blatant forms corporate fraud and non-compliance of regulations by the bank directors. Based on scanning of print media and discussions with bankers, including current officials and ex-governors and deputy governors of Bangladesh Bank, the following appears to be the case:

(a) Formal regulations clearly specify the autonomy of the management from the board and the roles of the board, chairperson, and managing director, but such regulations are rarely followed by the bank authorities. In most cases, it is the board that actually runs the bank.

(b) The BCA (section 27) prohibits PCBs from making loans to their directors and affiliated concerns, yet insider lending has been widely practised in the banking sector, especially by insolvent banks, leading to a huge accumulation of NPLs. Insider lending takes various forms: lending to firms with which bank owners have links, lending to family members of the owners and pure theft (i.e. the adoption of outright fraudulent strategies). The latter includes the transfer of funds by owners to fictitious accounts, taking loans without adequate collateral, and flouting banking rules. Some of these people are well-known business leaders, influential cronies, and benefactors of major political parties, and they have sufficient political capital to circumvent the central bank’s disciplinary measures (if they are used against them). Their formidable power also indicates those regulatory bodies like the MOF and Parliamentary Committees are to a large extent beholden to their special interests.

(c) Regulatory forbearance with regard to liquidity requirement, loan classification, accounting standards, or capital adequacy can be ensured by bribing or offering lucrative private sector jobs to the senior officials of the MOF.

(d) By using political connections with the MOF, the Parliamentary Standing Committee, or Prime Minister’s Office, one can successfully circumvent regulatory rules and restrictions.

As mentioned earlier, the BCA was first enacted in 1991 as part of the FSRP. The act provided for the licensing, supervision, and regulation of all banks.Footnote 52 The BCA also provided the legal basis for the central bank’s regulatory and supervisory role in the entire banking system. However, the private sector considers the act against its interests. Right after the Act’s amendment, the BAB and other prominent business associations (mainly the FBCCI) began a systematic campaign to further amend or simply end some of the more stringent rules and regulations. Organized business has successfully lobbied the political authorities in recent decades to relax, and in some cases completely reverse, the more stringent provisions in the act (prudential regulations in the process of repaying loans). In other cases (supervision of the central bank over internal management of PCBs), new rules have remained unchanged as compulsory formal laws in the book, but largely ignored by market actors in practice.

Non-compliance with the rules has been possible due to collusive linkages of these actors with the supervisory authorities (bureaucratic or political), at the highest levels of the hierarchy.

VI Summary of Findings and Concluding Observations

This chapter, by deploying both quantitative data and qualitative political economy analysis, has attempted to understand the institutional weaknesses of the banking sector in Bangladesh, while primarily focusing on the institutional loopholes relating to PCBs. Our analysis reveals the following features of the banking sector in this aspect:

While analysing the trend of key banking sector indicators over the past few decades, it appears that Bangladesh has made some important progress in terms of most of the indicators related to access, stability, efficiency, and depth of the banking system. However, the country in general is lagging behind other comparable developing countries in South Asia and Southeast Asia. Also, there has been a sharp rise in NPLs in recent years. High NPLs are considered a matter of concern for many Bangladeshi banks.

Our analysis, based on interviews with key informants, reports published in print media, and other research findings, indicates a number of institutional inefficiencies in the banking sector. One such key institutional weaknesses is the lack of autonomy of the central bank and the influence of the MOF in designing/altering key policies and strategies of the sector.

Our analysis also reveals the weak corporate governance of PCBs, under which PCBs act as closely held firms, that is mainly owned by a few large shareholders, who have strong control over the managers and where there are hardly any effective self-interested countervailing groups to prevent rampant corporate fraud and theft by the bank owners. The symptoms of weak governance have been reflected in frequent cross-lending and insider lending of PCBs based on personal connection/political influence, as well as in the strong influence of board directors in lending decisions. There is a prevalence of political patronage, favouritism and nepotism, crony capitalism, and state capture in the banking sector.

Interestingly, despite such inefficiencies and institutional weaknesses, except in a few cases, we do not observe any massive case of financial sector crackdown or bankruptcy as the Government either directly intervenes with financial support or instructs the central bank and/or NCBs to do so. Such a practice, though safeguarding the interests of depositors and protecting the sector as a whole, does so through large-scale recapitalisation and at the cost of tax payers money.

Sector-wide poor governance and institutional weaknesses, therefore, have weakened the financial base of the banking sector, primarily reflected in terms of inefficiency and NPLs. The consequences of this, among other things, are a high interest rate spread, continued fiscal burden, inefficiency in public spending, and large-scale capital flight, resulting in stagnant private investment, a slow pace of industrialisation, and rising inequality. All such consequences constrain the country’s ability to attain the Sustainable Development Goals and act as an obstacle towards growth performance.

Based on the findings, a number of recommendations can be considered for improved governance and greater efficiency of the sector:

Central bank autonomy: As discussed, one of the key institutional weaknesses of the banking sector in Bangladesh is the lack of autonomy of the central bank in governing the sector. As a consequence, we observe the formulation of policies in an ad hoc manner and not taking required actions against different malpractices of commercial banks. The central bank’s autonomy is therefore the pre-requisite for establishing good governance in the sector. In this context, it is needless to mention that such autonomy must be backed up with prudent management and an efficient workforce.

Modification of the BCA and strict adherence to it: Any amendment of the BCA must be made on the basis of economic considerations and without any political incentive. In addition, the existing act must be modified carefully to address the institutional weaknesses in terms of loan sanction, appointment of directors, penalty of defaulters, permission regarding establishing new banks, etc. A related policy would be to have supplementary policies for the provision of fresh loans where transparency should be the pre-requisite for granting any loan above a certain threshold.

Political commitment to penalise loan defaulters: Given the very high amount of NPLs, especially in recent years, and the political economy considerations behind this, there is no denying the fact that strong political commitment to penalise defaulters is necessary.