As I followed the Matsu people’s pilgrimages to Ningde, Fujian (2007) and Ningbo, Zhejiang (2010), observing the ups and downs, and the build-up of expectations and the concomitant disappointments of Matsu’s relations with China, I was constantly thinking that another project that sought to transcend the persistent cross-Strait adversities was perhaps not far off. As I expected, a plan to turn Matsu into an “Asian Mediterranean” arrived in 2012, and it quickly exploded and convulsed the islands. In this final chapter, I discuss this most controversial project, which will guide us deep into the Matsu society of today.

On December 25, 2008, the “three great links“ between China and Taiwan were launched. These links allowed more frequent and direct travel between the two sides, but they also spelled the end of Matsu’s role as a waypoint. The old “three small links” between Matsu and Fuzhou, which the government had been promoting since 2000, saw a steep decline in usage. Traffic between Matsu and Fuzhou numbered some 90,000 people in 2009. By 2011, it had been reduced to less than 40,000 people; in October 2011, there was only one voyage each day (down from two), and the ferry was usually nearly empty.

On the other side of the Strait, travel from Matsu to Taiwan has been a perennial problem. Although Matsu has two airports, in Nangan and in Beigan, they offer limited facilities, and owing to the unpredictable island climate, there are frequent flight cancellations. For instance, in 2011, the rate of flight cancellations for the two airports reached 19.4 percent (P. Zhang Reference Zhang2012). Some months are much worse than the average, such as May 2007, when a total of 135 flights were cancelled (H. Yu Reference Yu2007). Indeed, anyone traveling to or from Matsu even today will likely experience the frustration of cancelled flights and closed airports. Matsu locals often use a bit of doggerel to express their helplessness. The tourism bureau’s motto inviting people to Matsu was reinterpreted by the local people as: “Come ‘check out’ Matsu—once you come, you’ll never check out!” They also made up a joke offer, “Come to Matsu and get three free days in Guam!” (Lai Matsu song guandao sanri you) which was a pun for “Come to Matsu and you’re not ‘guam’ to leave for three days!” Behind these jokes lies a reality of the difficulty of travel to and from Matsu, and a corresponding feeling of helplessness among the locals.

As for maritime transport, the Taiwan-Matsu Ferry (hereafter Taima Ferry), the main ship connecting Matsu to the outside world, frequently breaks down. Operating since 1997, the ferry is now over thirty years old.1 Difficult sea conditions in the Taiwan Strait each winter often led to cancelled trips.2 On February 20, 2010, an accident occurred during a voyage. The Taima Ferry had just had its annual maintenance check and was transporting passengers for the Chinese New Year. Near the end of the holiday period, the ship was passing through the Taiwan Strait when it unexpectedly lost power, leaving eighty-five passengers adrift at sea for four hours.3 A new ferry, “Taiwan-Matsu Star“ (Taima zhi xing) was built in 2015, only to become known as “the breakdown ship.” After entering the water, the ship broke down at least once a month (J. Liu Reference Liu2015), and in 2016 and 2017, the breakdown rate exceeded ten incidents per year. Although that has improved recently, travelers still find themselves on tenterhooks.

Transportation problems and the anxiety they cause appear constantly in Matsu Daily and in discussions on Matsu Online.4 This chapter analyzes how a Matsu county commissioner attempted to face these transportation difficulties and to forge a wider regional network by bringing in a gaming plan proposed by an American venture capitalist—“Asian Mediterranean, Casino Resort” (Matsu dizhonghai, boyi dujiacun). This plan for a casino was hotly debated in Matsu before finally being put to a referendum. Even more importantly, a group of youngsters, the “post-WZA generation,” mobilized and participated in this event and began to exert their influence in Matsu politics afterwards. In this final chapter, I examine three important generations—the older fishermen from the fishing period, the middle-aged generation under the WZA, and the youngsters born in the post-WZA era, and explore their strikingly different imaginaries of Matsu’s future.

A Different Vision

Elected county commissioner in 2009, Yang Suisheng was a major advocate for bringing the gaming industry to Matsu, though the idea had already been brewing for a long time. In 2000, Cao Yuanzhang, the leader of the democracy movement who was then a member of the Legislative Yuan (discussed in Chapter 5), proposed building a casino resort, but the commissioner at the time opposed the idea. On March 8, 2003, Matsu Report conducted a phone survey, showing that 62 percent of participants were against the idea, while only 26 percent supported it (Matsu minzhong 2003). Given the county commissioner’s opposition, the proposal failed, but the issue continued to be actively debated on Matsu Online. After Commissioner Yang took office, the situation began to change.

Yang Suisheng was the first Matsu local to be sent to medical school in Taiwan under the guaranteed admission program. He began to participate in politics soon after returning to Matsu. In Chapter 8, I discussed Yang’s role in building a temple in Ox Horn and followed his journey to the head of the county commission. Through it all, his leading concern was the problem of transportation. He personally oversaw the purchase of the Taima Ferry from Japan during his leadership of the Bureau of Public Works. When I asked him why he focused so much on transportation, he confided in me:

In 1974, I began medical school in Taiwan, and each winter vacation I took a military supply ship back to Matsu. In the middle of a journey, an official military order came down saying that because important military goods were being carried on board, all non-military passengers would not be allowed in the ship’s hold, but instead had to stay on deck. It rained all that day, and combined with the waves, everything got so wet that there was no place to lie down. After a journey of more than ten hours, we were all totally exhausted. I saw that there was a row of military trucks parked on deck, and so I suspended my body across the wheels of two adjacent trucks. After a while, everything started to hurt, so I turned around and saw a cage of pigs on deck. I started to weep, thinking: “The Matsu people are even lower than the pigs.”

Later, I got married and had my first child. When my son was eight months old, my wife and I took him to Taiwan to see his grandmother. Not long after the ship left harbor, my son got seasick and wouldn’t stop crying. The ship officers were bothered by the noise and told us to go down to the anchor storage room. The waves were huge and the rolling ship sent the enormous anchor slamming into the walls, making an earsplitting noise all the way to Taiwan. I thought: I’ve had to suffer through a lifetime of excruciating sea voyages; will the next generation still have to be tortured in the same way?

In fact, because of ship or airline cancellations due to weather, both Yang and his son missed their respective university commencements in Taiwan (S. Li Reference Li2014: 7, 21). These wartime and personal experiences convinced him that only by improving the transportation to Matsu could the future of the islands be changed. When he was voted in as county commissioner, he began to implement a series of projects.

One of the projects involved replacing the Taima Ferry. After many complaints by Matsu officials to the Taiwan central authorities about the pervasive problems with the ferry, the Executive Yuan in Taipei finally approved the “New Taiwan-Matsu Ferry Purchase/Construction Plan” in 2009. The newly elected Commissioner Yang felt that if the new ferry were to be modeled on the old one, it would not prove competitive in the future. So in 2009, he put forth a proposal to purchase a trimaran instead (Fig. 10.1).

Fig. 10.1 shows a high-speed craft built by the Australian company Austal. It could make a one-way trip between Taiwan and Matsu in a mere three or four hours (compared to ten hours or more before); its hull was also resistant to high waves, making the journey much more pleasant (Qiuyue Liu Reference Liu2010). The planned passage would take the ship from Taiwan’s Keelung Harbor to Matsu, and then to Mawei in Fuzhou, before going back to Matsu and finally returning to Keelung. The commissioner felt that this route would be like a “high-speed rail for the sea” (haishang gaotie) since not only would the speed of travel increase convenience for the people of Matsu, but it would also encourage the movement of people between the three locations. The greater number of travelers would provide a boost to the local service industry and businesses (Yong santi 2010). In his desire to purchase a trimaran, the new commissioner was clearly thinking not only about solving the transportation problem, but also was hoping to use new maritime transportation technology to develop Matsu more generally.

The only flaw in the plan was that building the trimaran would require an outlay of 2.8 billion New Taiwanese dollars, more than twice the anticipated cost of a new ferry. The commissioner began a tireless campaign to lobby the central government (Qiuyue Liu Reference Liu2010). However, given that most Taiwanese were unfamiliar with trimarans and the high cost necessary to buy one, President Ma Ying-jeou finally declared in July 2010 that “the new Taima Ferry question should proceed in accordance with the original plan,” thereby rejecting the proposal to buy a new technologically advanced high-speed craft. As the commissioner described these events to me in 2014, his face revealed no frustration or disappointment. He said mildly:

Why am I telling you all this? Because even the president can’t fix Matsu’s problems. And that only made me more determined to bring the gaming industry to Matsu.

After that decision about the ferry, Commissioner Yang resolved to turn to outside capital.

Inspiration from a Poet

On January 12, 2009, the Legislative Yuan passed an amended Offshore Islands Development Act, with amendment 10–2 stating that the different islands could decide by legal referendum whether or not to allow gambling. In September 2009, the Pescadores Islands were the first to hold a referendum, and it was rejected. In Jinmen, a vote to allow the gaming industry was proposed in August 2009, but the proposal was withdrawn in October 2011.5 Thanks to Commissioner Yang’s persistence, on August 8, 2011, a gaming industry proposal was introduced in Matsu and produced a string of passionate debates and heated arguments. But how did the commissioner come up with the idea of bringing the gaming industry to Matsu in the first place?

Surprisingly, the idea originated with the celebrated Taiwanese poet Zheng Chouyu. After meeting the poet on three separate occasions, the commissioner decided to push the idea of bringing a casino to Matsu. The first meeting took place when the commissioner was involved in the development of Ox Horn (described in Chapter 8). At the time, he was the chair of the Ox Horn Community Development Association. He recounted:

One of my Taiwanese friends pulled some strings and we were able to invite Zheng Chouyu to Matsu to give a talk. While we were having dinner together, he suggested that Matsu bring in casinos. He said that casinos aren’t what most people think, and that they’re places that offer many different kinds of entertainment. That was the first time I’d even heard of the idea of a casino, and I didn’t really take it seriously.

The second occasion was at a banquet in Taipei, and this time Zheng Chouyu described in great detail the casinos on Native American reservations in Connecticut, which had proven to be very lucrative. The stories he told changed the commissioner’s image of gambling. He wrote about it on Matsu Online:

Three years ago, I had the chance to speak with Zheng Chouyu twice, and both times he mentioned the Native American reservations in the US. Owing to a lack of job opportunities, people had been leaving the reservations in great numbers. But in 1988, the US federal government issued the “Indian Gaming Regulatory Act,” and tourists began to stream in, improving the economy, creating all kinds of jobs, and bringing people back to the reservations. It completely changed the fate of the Native American reservations.

He also discussed the effects on Matsu of the recently developed religious tourism initiatives.

For the past few years, we’ve been trying to use the connection between “Goddess Mazu and the Matsu Islands” to develop “religious tourism” aiming at believers in Goddess Mazu. Although the effort has been ongoing for several years, we have yet to see any obvious results.

In 2009, the commissioner arranged to meet with Zheng Chouyu specifically to get him to expand on his ideas about the gaming industry.

The poet…talked about Macau and the Yunding Casino in Malaysia, and then mentioned how Singapore had recently built a casino, and then finally told me the story of how, when he was studying in Connecticut, he had worked as a dealer in a reservation casino. He had firsthand knowledge of and experience with the people who frequent casinos. As the poet said, a casino resort is like a goose that lays golden eggs, since people of all ages come together there and enjoy themselves.

He concluded:

Will Matsu vote to bring in the gaming industry? It might take a lot of discussion and public debate before we can have a vote. It could be an economic project, and good transportation will be a necessary part of that. It could also be a way of making a breakthrough on the transportation issue. No matter how you look at it, it’s something really worth exploring.

From then on, the commissioner not only actively advocated for the gaming industry in Matsu, he also welcomed casino capitalists to the area and helped them hold informational meetings across the islands.

The Arrival of the Casino Capitalists

Over the past few years, there has been a surge of interest in the gaming industry, along with the construction of many casinos, especially in Asia. Quite a number of new luxurious, large-scale casinos have been built in Macao and Singapore, and they have attracted huge volumes of international tourists. In 2007, the total income from Macao casinos surpassed that of Las Vegas, making Macao the world’s most popular destination for gamblers (Liang and Lu Reference Liang and Zhaoxing2010). The gaming industry’s success there has not only improved Macao’s economy by leaps and bounds, but also made it an example for the rest of the world. Many experts conjecture that Taiwan may very likely follow in Singapore’s footsteps and become the next country in Asia to allow casinos.

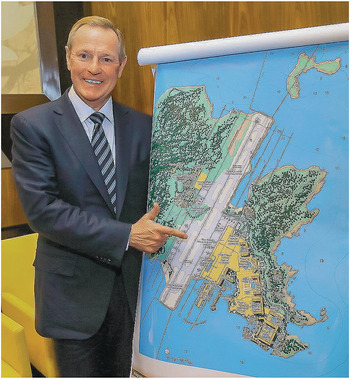

When Matsu spread the word that it might develop its gaming tourism industry, the American Las Vegas Sands Corporation, Australia’s Crown Melbourne, Malaysia’s Resorts World Genting, Macao’s City of Dreams, and other international gambling enterprises all sent representatives to Matsu to inquire about the possibilities that might open up there. The most enthusiastic among them was Weidner United Development Corporation. The head of Weidner United, William Weidner, had begun as the general manager of the Sands Corporation in 1995. His team, selected from his days in Las Vegas, had taken part in the development and management of the Venetian Casino Resort and the Palazzo Resort in Las Vegas, as well as the Sands Casino, the Venetian, and the Four Seasons Hotel in Macao. He also participated in developing the Marina Bay Sands in Singapore. In 2008, he left the Sands Corporation after a dispute with the founder Sheldon Adelson. He now runs Weidner Resort Development, Inc., and has a joint venture partnership with Discovery Land Company. He has also formed a collaborative entity called Global Gaming Asset Management with the global financial firm Cantor Fitzgerald, which seeks out casino resort development opportunities across the globe.6

As a global venture capitalist, William Weidner follows gaming trends in Asia closely. In 2008, when the Pescadores Islands were enmeshed in disputes over the issue, he was there to gauge the possibility of setting up a gaming industry. When the referendum failed in 2009, he moved on to Jinmen, even staying there from June to September 2011. But the then commissioner Li Woshi was not interested in bringing casinos to Jinmen. Weidner said:

Before I came to Matsu, I spent six months figuring out the situation in Jinmen. I could understand why the people of Jinmen didn’t want to open a casino. They have a lucrative brewery which is topnotch. Their lives are really nice. Even I’d want to retire there!

Weidner made his first trip to Matsu on March 4, 2011, when he met with the head of the county legislature. Having been thwarted in Jinmen, he turned his attention to Matsu. In October 2011, his staff began to come to Matsu to meet with local officials, and in January 2012, Weidner registered the “Taiwan Weidner United Development Corporation, Ltd.” with the Taiwan Business Bureau and rented space in an office building in the Xinyi District in Taipei. That same month, he gave a brief report to the Lianjiang County Government and prepared to launch his campaign in Matsu.

Matsu in the Eyes of Global Venture Capitalists

With a public proposal to bring the gaming industry to Matsu, many people in Taiwan began to pay attention to where a casino might be built. Even the billionaire businessman Terry Gou (the chairman of Foxconn) had something to say about the matter:

If you’re going to build a casino in Taiwan…it would be better to do it in Danshui. Not only would it bring jobs to the island, but it would also make Danshui an important site for tourism, technology, exhibitions, and so on, all in one spot.

Weidner was of a different opinion:

If you look at Google maps, you’ll see that the key cities of Fuzhou, Quanzhou, Xiamen, and Guangzhou are just an hour and a half away. So the way i see it, Matsu isn’t an “outer island”—it’s right in the middle of everything.

A reporter asked some follow-up questions about Terry Gou’s thoughts:

Question: Foxconn chairman Terry Gou has stated that building a casino in Danshui would be more profitable. What do you think about that? Is there somewhere on the main island of Taiwan that is more suited to a casino?

Answer: If you want to make money off of the people of Taiwan, then Danshui is a fine location. If you want to make money off of people from China and around the world, you should build it in Matsu. You’ll be making money from people who can afford to buy a plane ticket, instead of from people who are driving to the casino. (ibid.)

Weidner was clearly not thinking about Matsu in terms of Taiwanese consumers. China (or at least southeastern China) was his main objective. He had carefully analyzed how mainland China’s high speed rail system connected the major cities along the southeastern coast and had concluded that as far as land transportation from the west was concerned, Beijing, Shanghai, Wenzhou, Fuzhou, and other major cities were all linked by high-speed rail. In a single day, Chinese travelers could take advantage of the convenient transportation system to get to Fuzhou, the closest city to Matsu, and from there take a ship to the island. Once Matsu’s new airport was finished, tourists would also be able to fly there directly. Similarly, from the east, travelers from Taiwan could fly in from airports along the high-speed railway that connect all of the major cities from Taipei to Kaohsiung. Accordingly, he calculated that once the casino resort was operational, it could handle 12,000 visitors a day, or a total of around 4.5 million people a year, 70 to 80 percent of whom would come from mainland China. For a global venture capitalist, southeastern China was likely only a starting point: in the future, he would aim to bring in all of East and Southeast Asia (Weidner Reference Weidner2013: 89). Moreover, Weidner could take care of the finances and technologies without having to ask for government subsidies. He said confidently:

Some people say that the basic infrastructure of Matsu is lacking, such as water and electricity. I’m always surprised when I hear that. Haven’t these people ever heard of Dubai and Abu Dhabi? We built a city in a god-forsaken desert and accomplished so many impossible things.

At this point, there are all sorts of technologies like seawater filtration systems and biofuels to help us solve any problems we encounter. (Reporter: Are you saying that you plan to build a water filtration plant in Matsu?) I plan to build whatever will help me succeed. I can do it all myself, but I also would welcome help from the government if they wish. I’ve long since learned to deal with any limitations nature might throw my way.

Weidner boldly declared that he could do what the government could not; water and electricity for him were just the starting point. What other incentives did he offer?

Encroaching Neoliberalism

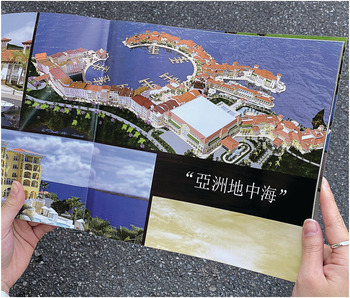

What Weidner wanted to build was not a simple casino, but rather a large-scale, integrated resort like Singapore’s Sands or Sentosa resorts. Weidner said: “To me, Matsu is like a charming little village in southern Italy” (C. Cao Reference Cao2012a). Thus, he named his planned resort village “Asian Mediterranean,” choosing Mt. Da’ao in Beigan and Huangguan Island in Nangan as his development sites. Beigan would house the Matsu Asian Mediterranean Resort Village with gaming facilities, while Nangan would be home mainly to five-star hotels and individual rental villas.

In order to attract tourists to these resort areas, Weidner would have to make major improvements to the basic infrastructure of Matsu, and this was a major part of the appeal the plan had for locals. These plans later developed into his so-called “four big pledges” (si da baozheng). First, he promised to build a Code 4 airport in Matsu (Codes 1–4 are designations used to indicate the length of a runway).7 He planned to upgrade the airport in Nangan from a Code 2 to a world class Code 4 airport, complete with a high-tech instrument landing system. With that in place, Boeing 737 and Airbus A320 aircraft would be able to land, and the people of Matsu would no longer suffer from delays due to heavy fog and bad weather. It would also connect Matsu to cities across mainland China, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. In addition, Weidner also planned improvements to the wharfs on Matsu. In his envisioned future, it would only take forty minutes to get from Langqi Island in Fujian’s Mawei district to Matsu, with each ship bringing up to 300–400 people.

To have a Code 3 or Code 4 airport has been a long-standing desire for the Matsu people. The county government carried out its own surveys and concluded that the airport in Beigan did have the potential to become a better-equipped Code 3 airport. However, it would require the removal of Mt. Duanpo, Mt. Feng, Mt. Da’ao, and Shi Island, among other areas, in order to allow for the safe approach of aircraft. A preliminary investigation of ocean depth also showed that if the runway were to be extended to a Code 4 standard, it would involve immense financial outlays. Meeting the Code 3 requirements was comparatively inexpensive and was therefore more feasible (P. Chen Reference Chen2011). Even so, a Code 3 runway would require an investment of more than NT$8 billion.

Second, Weidner promised to build a cross-sea bridge connecting Nangan and Beigan. Since he planned to build the casino resort on Beigan and hotels and villas on Nangan, a convenient link between the two islands would be needed. This bridge was what Matsu locals had been longing for. It had been repeatedly discussed in Matsu Daily, but the nearly NT$4 billion price tag was prohibitive.

Third, Matsu locals had long been dissatisfied with the state of their educational system, with only one high school across all the islands. Weidner agreed to set up a university in Matsu to help train people in various aspects of the tourism industry.

Fourth was the issue of the public good. Weidner pledged 7 percent of revenues to the local government as a special gambling tax. He estimated that if the local government gave half of that amount back to the local people, in the first year each person on Matsu could receive NT$18,000, and that number would go up to NT$ 80,000 by the fifth year.

Weidner’s “four big pledges” were undoubtedly an aggressive form of neoliberal infiltration, encompassing island-wide infrastructure (airport, bridge construction), higher education (university), economy (hiring workers), and public goods (dividends paid to Matsu locals). Were they to be realized, Matsu would doubtless become a “special economic zone” and the gaming businessmen would soon supplant the governance of the state.

Fantasy of an “Asian Mediterranean”

Weidner’s “Asian Mediterranean” plan involved much more than the provision of basic livelihood or economic development for the people; it proposed a grand reformation of the landscape of Matsu, engendering a vision of a place utterly different from the Matsu of the military period. He widely advertised his plans on all kinds of media.

Isolated Islands vs. Interconnected Archipelago

Let us start with the cross-sea bridge connecting Nangan and Beigan. During the WZA era, each island was engaged individually in the war effort, with an emphasis on “one island, one life,” and no one could ever imagine an inter-island bridge. Even after the dismantling of the WZA, each island’s transportation system was developed separately. There was no way to share resources between the islands because of their dispersion. The fact that many vital constructions had to be duplicated on different islands was an enormous problem for the Matsu government (for example, Nangan and Beigan both needed to have an airport, which meant the facilities of each were simple and limited). If the islands were to be connected, resources could be shared; each island could then develop its own characteristics and functionally complement each other. Weidner’s “four big pledges” thus struck a chord in the hearts of the people.

Marginality vs. Internationality

When I asked Liu Dequan, former head of the Matsu Tourism Bureau, about his thoughts on Weidner, with whom he often interacted, he said:

Weidner and his team had a vision and painted a picture for us, while the other brokers just asked how much land Matsu has. They’d done a lot of research into the advantages of the area where Matsu is located—centered on Fujian, including Zhejiang to the north, and northern Guangdong in the south.

They also had an understanding of Matsu itself. The places they proposed, Nangan’s Huangguan Island and Beigan’s Mt. Da’ao, are both chosen from the perspectives of the airports. They are also separate from the main islands, and the soil is poor there. Since no one lives there, it would be easy to develop.

He imagined a step further:

After the plan succeeds, Matsu will be totally transformed from Taiwan’s outlying islands into an international archipelago. Taiwan might one day even become an outlying island of Matsu!

Clearly, Weidner’s imaginary of the future—namely of Matsu as an international archipelago—was deeply attractive to the Matsu people, who are facing an imminent crisis of marginalization.

Cold War Island vs. Luxurious Seaside Resort

The lure of a modern C4 airport was even more enticing. Not only would it solve the ongoing issue of transportation for Matsu locals, it would also bring in waves of tourists who would completely alter the bleak condition on the islands (Fig. 10.2). The global venture capitalists’ “Asian Mediterranean Project” promised to transform Matsu from a peripheral warzone island into a charming vacation island like the exotic resorts in the Mediterranean Sea. Matsu would be another Dubai, a fantastic vision erected in the middle of the ocean.

Let us look more closely at the theme of “Asian Mediterranean.” The Matsu casino resort was quite different from the one designed for the Philippines, which we will discuss in the following section. Since the traditional dwellings in Matsu bear some resemblance to the style of villages in the Mediterranean, Weidner imitated the flavor of Italy—areas around the Mediterranean sea and in Southern Tuscany in particular—as well as villas in Monaco, to create a sense of the exotic for the resort (Fig. 10.3) (Hong Reference Hong2013).

In the animated 3D images that Weidner designed, Matsu’s bitterly cold winter that keeps people huddled indoors is completely absent. It is replaced by constant sunshine, villas, wharfs, speedboats, and a sparkling blue sea. The Matsu archipelago is filled with the bustling tourist atmosphere of the islands in the Mediterranean. This imaginary of Matsu was endlessly circulated through publicity materials, in online venues, and across new media.

Reality or Dream?

We must ask, however, whether the image of Matsu propagated by these global venture capitalists was real or fake. Would it be possible to achieve in reality? For Matsu locals, it was impossible to judge. This new imaginary existed somewhere between truth and fiction. At the same time, Weidner packaged this imaginary with a series of neoliberal ideas: that is, his putative global, capitalist, non-local network (see Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1999, Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2000, Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2002). The mixture of his ceremony-like presentations with these neoliberal ideas only served to make the entire concept of an “Asian Mediterranean” even more indistinct and mysterious.

As described above, the plan that Weidner put forward was built with an understanding of the Matsu Islands’ condition. When promoting his casinos, Weidner and his working team sought out contact with locals. They set up an office in Nangan and held large informational meetings on the two major islands. The members of his team also went out to each village to hold smaller local meetings. The day before the vote, they used the familiar Taiwanese tactic of “carpet campaigning,” fanning out across areas likely to vote against the measure to try to sway voters. Below is a description by Xu Ruoyun, one of Weidner’s team members, from July 6, 2012, the night before the vote:

Xu Ruoyun: Starting at 4pm, we went door to door across Ox Horn and Shanlong. We knocked on every single door, talking to a lot of people who were against the casino and weren’t happy to see us. We didn’t even stop to eat. The worst of it was going to Shanlong [an area with a relatively high proportion of civil servants and school employees]. …It was raining, and we were miserable [Matsu villages are built into the mountainsides, with pathways of uneven steps. They can be difficult to navigate in the rain]. In the end, the heavens were on our side, and we won in each balloting location! Only in Shanlong did we come in tied, 329 to 329. That means we didn’t lose in a single district.

Author : And Weidner himself?

Xu Ruoyun: He arrived three or four days before and canvassed with us. The night before the vote, he came out with us, going door to door to ask for people’s votes.

However, in terms of “the reality on the ground,” it truly was a “borderless fantasy.” Weidner liked to display his wide network of contacts in well-laid-out advertisements and on official occasions. But these contacts were all from the outside world, and for Matsu locals, they were just a series of unknown faces. Weidner’s publicity materials were full of international partners who were “big entrepreneurs” with no ties at all to the area. These contacts frequently appeared only for ceremonial occasions such as big informational meetings or press conferences (Fang Reference Fang2012). No one knew who these men in fancy Western suits and women in perfume and heels were, nor what part they were supposed to play in Weidner’s plan.

Moreover, Weidner held press conferences to keep a steady stream of publicity going, announcing that he had brought in more investments from international banks for the casino resort. Each monetary figure mentioned was higher than the last. The media was giddy with excitement:

…An American entertainment company held a high-profile press conference in Taiwan on the 9th to announce that it will head a team to develop Matsu’s tourism industry, as well as to publicize its success in raising NT$60 billion from Wall Street financial institutions.

In America, he discussed raising capital with eight large financial institutions, including Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank, UBS, J.P. Morgan Chase Securities, Merrill Lynch, CLSA Capital Markets Limited, Credit Suisse, and the Macquarie Group. NT$60 billion is only for the first stage, and the plans have been extended to the third stage, with total possible investments reaching somewhere around $NT180 billion.

[Although] Taiwan’s Weidner United holds NT$1 million in funds, Weidner’s holding company does US$16 trillion worth of securities trading with companies on Wall Street. They pledge NT$70 to 80 billion for the first stage of development, and over the course of three or four stages in 15 years, the total investment will be more than NT$240 billion. The company has already raised US$3 million.

The proclaimed amounts of total investment kept on increasing, from NT$60 billion to NT$180 billion and all the way up to NT$900 billion, but for the Matsu people, there was no hard confirmation of these sums. For them, it was difficult to tell truth from fiction. Weidner also never directly addressed people’s suspicions; for example, at an informational meeting in the town hall in Nangan:

Weidner personally introduced the management for the project, including the Director General for Asia, his international gambling analysts and several other members of the development team who were present at the informational meeting. A video was shown by Weidner United describing their plans for Matsu. …As for some concerns expressed online about the amount of capital raised, Weidner smiled and said that a Wall Street investment bank affirmed that Weidner United had received a single investment in the amount of NT$60 billion.

Instead of responding directly, Weidner just smiled and dangled the number of 60 billion before the audience.

In order to further demonstrate his economic power and ability to raise funds, Weidner took advantage of the opening ceremony for the Solaire Manila Resort—in which he was one of the investors—to invite twenty-two reporters from Taiwan to the Philippines (Song Reference Song2013). He held a press conference there so he could elucidate his plans for Matsu to them, emphasizing how he would apply his experiences in Malaysia to the planned casino resort in Matsu (Fig. 10.4). Solaire Manila Resort is set on one hundred hectares of land overlooking the Manila Bay Entertainment City. Plans for the Entertainment City included four casino resorts, among which Solaire was the first to open, with the other three still under construction. Weidner was collaborating with Solaire’s parent company, Bloomberry Resorts Corporation, and had provided around 10 percent of the total investment.

Fig. 10.4 Weidner in the Philippines introducing plans for a casino in Matsu

In this series of actions, Weidner, acting as a global capitalist investor, used borderless capital as a kind of underpinning for his plans (see Miyazaki Reference Miyazaki2006: 151). Aided by the extravagant ceremony-like meetings, he gave the marginalized people hope, even if it was for a fantasy-filled and as-yet undecided future.

Casino or Home?

The issue of whether or not to develop the gaming industry as a key part of Matsu’s future was a pivotal one that affected everyone on the islands, and so it attracted wide attention. When an occasion arose to ask older fishermen about their attitudes towards opening a casino on Matsu, many expressed support for the idea. Aside from the “NT$80,000” payout to locals that would help support their retirement, they also felt that there was nothing wrong with gambling:

We all used to gamble!

Everyone on Matsu likes to “take a little gamble”—it’s in our nature!

As Chapter 4 discussed, gambling was a part of the fishermen’s lifestyle. Now that the fishing economy has declined, and the military is gone, the fishermen’s attitude is “there’s nothing left, so why not gamble and see whether we can get something (F. huang lung tou mo lou, puh y tu luoh tu),” according to a popular saying. The idea that something had to be done proactively in order for there to be any hope is not that different from the old belief of fishermen that every opportunity must be seized as soon as it arises, and it fed the feeling that any change for the better necessarily comes with a certain degree of risk.

There was another group that supported the gaming proposition, namely, educated people who had moved from Matsu to Taiwan. They not only conducted a forum on gambling in Taiwan, but also returned home to actively argue for the casino. Chapter 3 discussed how the guaranteed admission program led to the emergence of a new social category of civil servants and teachers in Matsu. Having fulfilled their obligation to return home and serve Matsu, they were then confronted with the difficulty of transportation to Taiwan and limited prospects for promotion, and many decided to return to better conditions in Taiwan. Their economic situation in general is better than the manual workers who had migrated to work in factories in an earlier era; many were able to buy homes in the greater Taipei area which were comparatively expensive. They even set up their own Matsu “Teachers and Civil Servants Association” (wenjiao xiehui) in 1997.

It quickly becomes apparent when speaking to these emigrants that many of them grew up in the WZA era and remember that period as one of constant hardship. They view the decline of the fishing industry and the limited job opportunities as part of life in Matsu, and see it as the reason they had to leave and make their mark elsewhere (L. Zhang Reference Zhang2012). They felt that if Matsu did not grow its own industry, it would continue to be reliant upon the central Taiwanese government, and the future would be bleak (J. Lin Reference Li2012). Others believed that large financial consortiums would have enough capital to develop the region (S. Cao Reference Cao2012), thereby bringing hope to Matsu. Their memories of “hardship” and “being unable to stand on our own two feet,” along with their support for “development,” are primarily responses to their own histories as immigrants. These experiences are quite different from those of the younger generation who grew up in Matsu, and so their standpoints on the casino question also diverge.

One example from the middle of the age spectrum succinctly expresses the transition in the imaginaries of Matsu. Cao Xiangguan was born in 1970, and so was only forty-two years old during the push by the gaming industry. He is typical of many middle-aged locals in that he was sent to study in Taiwan as part of the guaranteed admissions program and came back to Matsu to serve in the government. He studied maritime engineering, which was badly needed in Matsu. When he returned home, the military government was just in the process of being dismantled; at the time, many of Matsu’s harbors were very crudely equipped. He immediately began to work on wharf construction and improvement, spending a decade in the industry. Over the course of engaging in these projects, however, he came to realize that there was no long-term plan or overarching vision for Matsu’s development, but instead only constant destruction: the thoughtless installation of docks, dykes, and anti-wave concrete blocks was destroying Matsu’s shoreline and coral reefs. Obviously, Weidner’s plans for a casino resort would involve a tremendous amount of land reclamation, at great cost to the natural environment and ecology of the area. When I talked to him in 2018, he used an image of a family to describe the support for the casino shown by the many educated Matsu people living in Taiwan:

Take a poverty-stricken family, in which the father decides to leave the village to go out and earn money. He leaves behind his wife, who has the children to take care of and who works hard herself. After many years of struggling to make it, their situation improves. One day, the father returns home from his job outside the village. He doesn’t understand how hard his family members have been working while he’s been gone. He thinks of them as backward and behind the times, and he wants his wife and children to sell or rent out the family property to make money.

This story of “family” not only serves as a metaphor for the relationship between emigrants, locals, and venture capitalists promoting gaming; it also relates to the imaginary of Matsu that many of the younger generation hold.

Debate over the gaming industry had been going on in Matsu Online forums for quite some time, but the clearly demarcated camps for and against had little effect on the average people in Matsu. Taiwan’s anti-gambling legalization association also came to Matsu and formed the frontlines of the battle early on, setting up a fan page on Facebook called “Long live Matsu, don’t turn our home into a casino.” But the page never caught on with Matsu locals, who saw it as outside interference. In contrast, the side favoring development was dominant under the influence of the Matsu government and the support of migrants. The opposition did not really get off the ground until a group of young anti-gambling activists joined in, and the numbers for and against the proposal began to fluctuate.

The Counterattack from the Post-martial-law Generation

Cao Yaping, the organizer of this group of youngsters, was at the time a 23-year-old student at a research institute for social development in Taiwan. Born in 1989, she was different from other members of the opposition in that she had grown up in post-WZA Matsu and had no real experience with military rule. Cao said that when she studied the negative repercussions of development, the cases were all about indigenous peoples and disadvantaged groups. She had never considered that these issues might apply to her homeland until one day she returned home and was shocked to hear her father, the owner of a shop selling local products, expressing delight at the prospect of a casino being built in Matsu. “People of my generation first understand the outside world, and only then do we come to understand Matsu,” she said. She went back to Taiwan and began to appeal to other Matsu youngsters by organizing an anti-gaming online community and setting up a Facebook page called “Matsu youth against gambling: We don’t want a casino future.”

This group slowly gathered steam and not a few young people expressed their feelings on the page. More importantly, the users took advantage of the different “share” functions, posting information from the anti-gambling page to other websites and thereby extending their reach. The most famous post was an essay titled: “A thirteen-year-old girl sent me a message to tell me that I have to keep up my anti-gambling efforts.” It came from a message written to Cao Yaping by a girl who had gone to elementary school in Matsu, and it recounted the unspoiled beauty of the Matsu scenery as well as her dread of the islands becoming a gambling den. Cao first posted the essay on her personal blog, and then made public posts on Facebook and Matsu Online. It eventually went viral and received substantial coverage from all of the major media outlets in Taiwan. The Matsu casino suddenly became national news and attracted wide attention. In Matsu, educators began to see their students stand up, and they too started to support the movement. The energy and wholesomeness of the students moved many of the middle-aged generation, and brought more people to the cause. One of them wrote on Facebook: “Because [of them] we can see Matsu’s future!” Public opinion, which had originally leaned toward the anticipated passage of the proposal, gradually became less and less certain (Pan Reference Pan2012). In the end, even though the students lost the vote, the appearance of these young people opened up a different future for the islands. They constitute a growing force in contemporary Matsu politics.

The active political participation of the youngsters indicates that their image of Matsu, Taiwan, and even Fuzhou is very distinct from that held by the older generation of fishermen or the WZA generation. Importantly, this post-martial-law generation did not experience the hardships of military rule. The Matsu they know is developing tourism, and whether in terms of transportation, lifestyle, or accessibility of information, their Matsu is closely linked to Taiwan. For example, Cao Yaping mentions an experience from her childhood:

I’ve been going to Taiwan since I was a kid. Over the summers, I’d meet friends in Taipei, and we’d walk around Ximending [the most popular shopping area for Taiwanese youth]. It just felt natural to visit Taipei from Matsu.

She even reverses the older generation’s idea of the relationship between Matsu and its neighbors, Taiwan and Fuzhou:

Taiwan and even Fuzhou are like Matsu’s “backyard.” We go there to hang out, to take extra prep classes, or to go shopping.

Thus, for the post-martial-law generation, Matsu is no longer an isolated place—it is neither a temporary stopover nor a military frontline. Thanks to the connectivity brought about by improved transportation and digital communications, Matsu has gradually become their “home,” where they can live and work with a measure of stability. In contrast, Taiwan and Fuzhou are now their “backyards,” which they visit for entertainment in their leisure time or whenever they want. This is a totally different image of their lived world. Their rejection of the casino project in Matsu reflects their longing for the sustainable development of their home that is no longer controlled by the army or damaged by outsiders.

Conclusion: Fissured Future

In the end, the proposal for the casino won 1,795 votes (57 percent) to the opposition’s 1,341 votes (43 percent). Supporters propagated the idea that the proposal would provide a marginalized Matsu in crisis “another source of hope” (duo yige xiwang), or allow it to “seize an opportunity” (zhangwo yige jihui) , or even let its people “bet on the future”(du yige weilai), actively reaching out to a population mired in transportation and economic difficulties.8 If we say that the Matsu people in the fishing period gambled with the ocean, and in the military period with the state, now in the twenty-first century they voted to gamble with their future. The fisherman’s mindset continues to be a way for the islanders to struggle with uncertainty in the twenty-first century.

Matsu still does not have a casino resort. Although the measure passed a public vote, the central government must formulate a set of new laws, such as the “Regulations for the Supervision of Tourism and Casinos.” Only when the local government sees the laws can it begin to attract subsidiary businesses and investment. The necessary bills, however, have been blocked in various ways in the national legislature. A February 2013 decision by mainland Chinese officials, indicating that they would ban travel to the Matsu casino, has made the plan seem even more unrealizable. Finally, in June 2015, Weidner announced that he would pull out of Matsu, as the Taiwan government had not shown any intention to cooperate for three years.

The fact that the idea of a casino resort could begin in an individual’s imagination and go on to capture the imagination of a whole society is an expression of the constant vicissitudes that the Matsu people have faced. From 1992, the end of military rule, and all the way to the “three great links” between China and Taiwan, the people of Matsu have faced unprecedented challenges. It is undeniable that the imaginary of an “Asian Mediterranean” offered by the casino capitalists spoke to deep desires that the people of Matsu already harbored; or one could say that it fit their dreams. Through the image of an “Asian Mediterranean,” Matsu locals were not only able to reimagine themselves as repositioned between the two sides in the Taiwan Strait, and to reframe the islands as able to reach the whole of Asia, they were also able to make an incipient entry onto the world stage. For most Matsu locals, this was indeed a “new opportunity”—irrespective of its complex mix of hope and despair, promises and disappointments, present and future.

This kind of new opportunity also reveals an important characteristic of the contemporary imaginary: the imaginary offered by the venture capitalist, William Weidner, did not come from traditional myths or stories (Taylor Reference Wang and Qiu2004: 23), nor was it based on local sociocultural forms. Given this circumstance, its resemblance to a fantasy is even more pronounced; it was mediated by global capital, non-local networks, and glittering “showbiz” performances. Reality and fantasy not only became difficult to distinguish, but also mixed with illusions to stimulate people’s thoughts and fervor. Clearly, imagination is a crucial characteristic of local societies today. This kind of fantasy may appear absurd at first glance, but it is a genuine way for people on the periphery to respond to marginality and to explore their own possible futures.

The case of Matsu offers an excellent example of the process of imagination, which started with an individual and went on to become social and shared more generally by the greater society. As pointed out, in 2003, two-thirds of the population of Matsu opposed building casinos, while by 2012, the proposed casino resort won more than half of the vote. The important mediators were the grandiose dream offered by a global capitalist, and an imaginative figure, Yang Suisheng, who was able to connect the local and the global. As discussed earlier, Yang had received a modern medical education but was born and raised in Matsu. He was perennially caught between science and tradition. Early on in his career, he served as the chair of the Ox Horn Community Association and hoped to reinvigorate his home while also protecting the environment. With little success to show for his hard work, he threw himself into building a temple and gained the support of locals, eventually becoming county commissioner. While serving as commissioner, he realized that pilgrimages and other religious attractions would not usher in the benefits that locals were hoping for, and he decided to forge an alliance with the casino capitalists in order to bring new opportunities to Matsu. These sorts of figures, mediating between local places and the greater society, along with the kinds of imaginaries they offer, always prompt new thoughts and actions in local society, even if in the end they may not be able to solve the underlying problems.

The conflict, debate, and tension surrounding the casino proposal reveal the divisions between different generations in Matsu—the fishermen during the fishing period, the civil servants and teachers arising from the WZA era, and the younger generation born after the war period—and their different imaginaries of the future. Today’s social imaginings are in no way unitary, nor can they be understood with a top-down model. How these different imagining subjects understand their lived world and their expectations for the future are important questions to consider when we study contemporary society.