The preceding chapter provided a purposefulness framework to guide a law school in realizing the four PD&F goals of helping each student to understand and internalize

Ownership of continuous professional development toward excellence at the major competencies that clients, employers, and the legal system need;

a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, especially the client;

a client-centered, problem-solving approach and good judgment that ground the student’s responsibility and service to the client; and

well-being practices.

This chapter explores what legal education can learn from medical education’s much more extensive experience in giving purposeful attention to the four PD&F goals. Even if a law school declines to go “all in” on competency-based education, medical education’s experience provides insight into purposefulness to foster student growth on these foundational goals.

3.1 Medical Education’s Move toward Defining Core Competencies and Stages of Development on Each Competency

Drs. Robert Englander and Eric Holmboe and other medical educators observe that throughout most of the twentieth century, education in the health professions and the delivery of health care services prioritized the technical expertise of the health professional and the health professions educator. Education focused on (1) a certain number of exposure hours of credit (called a “tea-steeping” model, with the student akin to a tea bag submerged in a cup of hot water for the right amount of time) and (2) academic outcomes like multiple-choice tests and licensing exams addressing technical knowledge. The student’s education did not address what the licensed graduate can actually do to meet patient needs. Curricula were organized by discipline or subject and faculty-produced lessons delivered in a one-size-fits-all package of “goods” to passive learners. Little attention was paid to the learner experience.Footnote 1

In the 1980s and 1990s, concerning signs of problems in the quality and safety of health care percolated through the health care system. By the late 1990s, the medical education community realized that it was not sufficiently preparing students to meet the challenges of a dynamic and changing health care system.Footnote 2 Medical educators came to understand that the narrow emphasis on medical knowledge and cognitive skills was inadequate to meet patient and population needs.Footnote 3 The earlier approach of “if you are really smart cognitively, you’ll be fine” was not sufficient.Footnote 4 Medical educators realized the central importance of a much broader framework of patient-centered care – one that recognizes that cognitive technical skills are necessary but not sufficient to meet patient and health care system needs.Footnote 5

By 2000, the pendulum had swung toward stronger emphasis on patient-centered care in the delivery and improvement of health care services and stronger emphasis on learner-centered and learner-driven medical education that focuses on the student’s demonstration of the full range of competencies that a graduate needs to provide patient-centered care.Footnote 6 Medical educators adopted competency-based medical education (CBME) to guide this change. CBME is defined as “an outcomes-based approach to the design, implementation, assessment, and evaluation of medical education programs, using an organizing framework of competencies. A competency describes a key set of abilities required for someone to do their job.”Footnote 7

3.2 Lessons Learned in Moving toward Competency-Based Medical EDUCATION (CBME)

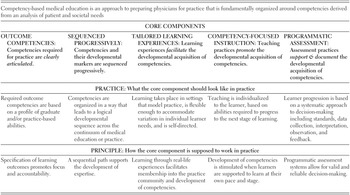

In a multistage process drawing on scholarship from education theory and medical education, fifty-nine members on an international CBME expert panel identified five core components to CBME.Footnote 8 The panel presented its vision of the five core components of CBME in a table reproduced here in Table 10.

Table 10 The five core components of competency-based medical educationFootnote 15

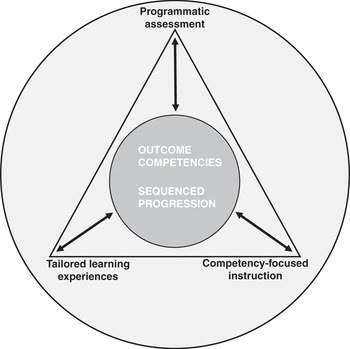

Of the five core components in Table 10, the expert panel envisioned “Outcome Competencies” and “Sequenced Progressively” as the central core components guiding competency-based medical education.Footnote 9

As Table 10 shows, medical educators started by identifying the needs of patients and the health care system. Only then could they define the critical competencies flowing from those needs that each student should develop and demonstrate.Footnote 10 With the critical competencies identified, medical educators could take the next step of sequencing the competencies, and their developmental markers, progressively.Footnote 11

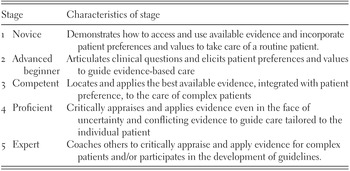

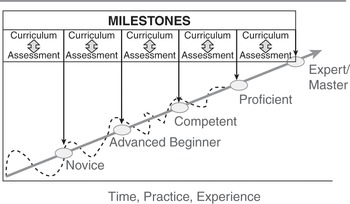

Medical educators use the term “Milestones” to describe narrative models of how student development of a core competency moves through stages toward a level of competency necessary for a licensed physician to serve clients adequately.Footnote 12 The Milestones on a specific competency provide a “shared mental model” of professional development starting as a student and progressing to competent practitioner and, beyond, to mastery.Footnote 13 A Milestone model defines a logical learning trajectory of professional development. It also highlights and makes transparent significant points in student development using a narrative that describes demonstrated student behavior at each stage.Footnote 14 Milestones can be used for formative and summative assessment as well as program assessment. If faculty and staff adopt a Milestone model for a particular competency, they also are building consensus on what competent performance looks like and thus will foster inter-rater reliability of assessments. Because Milestones describe what a trajectory should look like, learners can track their own progress toward becoming competent at a particular competency and programs can recognize students who are advancing well or in need of extra help.Footnote 16 Overall, each Milestone reflects the Dreyfus and Dreyfus model of development from novice to expert shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Milestones reflect the Dreyfus and Dreyfus model of development from novice to expert for each competency (such as the lawyer competencies shown in Figure 1). Law firms commonly call these “benchmarks.”Footnote 17

Table 11 reproduces an application of the Dreyfus model developed by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) to define the stages of development for patient-centered, evidence-based, and informed practice. (The reader should note that this goal or competency is similar to the third PD&F goal that we advance in this book for lawyers: a client-centered problem-solving approach and good judgment that ground each student’s responsibility and service to the client.)

Table 11 ACGME harmonized milestone on evidence-based and informed practiceFootnote 18

The ACGME developed a Milestone Model for Reflective Practice and Commitment to Personal Growth that is useful for legal education to emulate in modeling stage development with respect to PD&F Goal 1 – ownership of continuous professional development toward excellence at the major competencies that clients, employers, and the legal system need.Footnote 19 Similarly, the ACGME’s Milestone Model on Patient-Centered Communication can be emulated with respect to PD&F Goal 2 – a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, especially the client.Footnote 20

The Milestone and Dreyfus models contemplate that learners take ownership over their own continuous professional development to later stages on each of the competencies needed.Footnote 21 (This matches up squarely with the first PD&F goal.) Learners in a competency-based education system “must be active agents co-guiding both the curricular experiences and assessment activities.”Footnote 22 What does it mean for students to be active agents in their own learning and assessment? “Learners must learn to be self-directed in seeking assessment and feedback.”Footnote 23 Ideally, learners should

1. Be introduced to the overall competency-based education curriculum at the beginning and engaged in dialogue about the overall program on an ongoing basis;

2. actively seek out assessment and feedback on an ongoing basis;

3. proactively do self-assessment with feedback from external sources and reflect on both;

4. direct and perform some of their own assessments, such as seeking out direct observation of the learner by an experienced professional and creating portfolios of evidence regarding specific competencies; and

5. develop personal learning plans that are revisited and revised at least twice a year.Footnote 24

With respect to the third core component of CBME outlined in Table 10 (tailoring learning experiences that model practice to accommodate variation in individual learner needs) and the fourth component of CBME (promoting student development by individualizing teaching based on the abilities required to progress to the next level), Table 12 explains the major differences between traditional medical education and CBME.

Table 12 A comparison of traditional versus competency-based medical educationFootnote 25

| Variable | Traditional Education Model | CBME |

|---|---|---|

| Driving force for curriculum | Knowledge acquisition | Knowledge application |

| Driving force for process | Teacher | Learner |

| Path of learning | Hierarchal | Non-hierarchical |

| Responsibility of content | Teacher | Teacher and learner |

| Goal of educational encounter | Knowledge and skill acquisition | Knowledge and skill application |

| Type of assessment tool | Single assessment measure (e.g., test) | Multiple assessment measures (e.g., direct observation) |

| Assessment tool | Proxy | Authentic (mimics real profession) |

| Setting for evaluation | Removed | In clinical and professional settings |

| Timing of assessment | Emphasis on summative | Emphasis on formative |

| Program completion | Fixed time | Variable time |

The change from traditional medical education to CBME began in 2000, and it is still a work in progress. Implementation has been slow, especially in primary-degree schools that remain steeped in tradition and equate curriculum with exposure hours.Footnote 26 CBME is a major shift in thinking, and faculty members have lacked a shared mental model of developmental stages and standards regarding many outcomes.Footnote 27 Two decades since the shift began, medical education remains in the midst of transformation.Footnote 28

3.3 Applying Lessons Learned from CBME to Legal Education

Legal education has begun its journey toward competency-based legal education (CBLE). ABA accreditation standards were revised in 2014, and by 2020, nearly all law schools in response had published learning outcomes as a first step toward CBLE. Further requirements are likely to follow. It is realistic to anticipate that the ABA as an accreditor, along with the regional accreditors for the universities with law schools, eventually will compel law schools to take the next steps beyond mere adoption of learning outcomes. If medical education’s experience is any guide, legal education’s movement toward CBLE will be gradual over several decades.

The good news for legal education is that the core conceptual features of a sound model of competency-based legal education are already at hand, thanks to medical education’s path breaking. The structure and logic of medical education’s competency-based model, depicted in Table 10 and Figure 3 earlier, are directly applicable to CBLE. Table 10’s five core CBME components and Figure 3’s emphasis on “Outcome Competencies” that are “Sequenced Progressively” in CBME translate easily to legal education. A competency-based legal education inspired by and modeled on CBME is depicted in Table 13 and Figure 4.

Table 13 The five core components of competency-based legal educationFootnote 29

Developing a law school curriculum that employs “Outcome Competencies” that are “Sequenced Progressively” as contemplated in Table 13 and Figure 4 requires identification of the needs of clients and the legal system and then, in turn, specification of the core-competency learning outcomes that each student must develop and demonstrate to meet these needs. Work to that end is underway in legal education. The Foundational Competencies Model in Figure 1 in Chapter 1 is a synthesis of the best available empirical data on the competencies that clients and legal employers need. And Figure 2 in Chapter 2 illustrates the kind of sequencing models that working groups established by the Holloran Center are devising.

Figure 4 Competency-based legal education’s two central core components informing the three other components in local CBLE programsFootnote 30

In the next chapter, we will discuss ten key principles to guide legal educators who are interested in fostering student growth toward the four PD&F goals. Those principles are drawn from the five Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching studies of higher education for the professions, CBME, scholarship on higher education generally, and moral psychology. One key take-away from CBME to carry forward into the next chapter is that Milestone Models for PD&F goals have substantial benefits for all the major stakeholders in legal education. Table 14 outlines these benefits.