As an indication of improving trade between the colonies and the East, the inauguration of a new steamship service under the auspices of the Japanese Mail Steamship Company is an event to be welcomed, and in the Yamashiro Maru, the pioneer vessel, which arrived here yesterday, the proprietors of the service have presented a steamship which should at once commend itself to the travelling public.

And in that water lies our sacred Law.

Not just near the foreshore. We sing from the shore to where the clouds rise on the horizon.

A Map

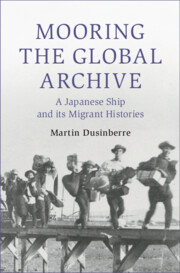

In its heyday, the Yamashiro-maru was known not only for having transported thousands of Japanese labourers to Hawai‘i but also for having opened the NYK’s monthly service to Australia. Beginning in October 1896 and in rotation with two other company ships, it steamed from Yokohama to Melbourne via Hong Kong every three months until the end of 1898, when it was replaced on the route by a newer, bigger vessel.

In my initial online research for this period of the ship’s life in 2012, I came across a man who took early advantage of the new Japan–Australia line, possibly after reading reports of its official opening in the Japanese newspapers.Footnote 2 Hasegawa Setsutarō was born in the Hokkaido port of Otaru in 1871 and trained as a schoolteacher. Having applied for a passport at the end of 1896, he arrived in Australia on the Yamashiro-maru in February 1897, travelling in steerage with one other Japanese and nine Chinese passengers. According to oral history interviews given by his daughter-in-law in the mid 1980s, he came to Melbourne to learn English, lodging at the residence of a certain Colonel Tucket as a ‘houseboy’. But having allegedly been badly treated by his employer, Hasegawa ended up in Geelong, where he became one of four Japanese laundry owners. Marrying Australia-born Ada Cole in 1905, he and Ada brought up three sons before divorcing in 1914. After his attempt to open an import–export company failed during the First World War, Hasegawa returned to the laundry business, where he worked until his internment as an enemy alien in December 1941. During the war, two of his sons permanently adopted their mother’s maiden name in an attempt to avoid anti-Japanese discrimination.

Upon his death in 1952, Hasegawa left his family a collection of documents, objects and clothes, which they later donated to Museums Victoria.Footnote 3 Among the surviving possessions which he brought from Japan in 1897 was a Ministry of Education-approved textbook of English lessons by Reverend D. A. Murray, then head of a commercial school in Kyoto. The book speaks to Hasegawa’s training as a teacher, to his hopes for a new life in Melbourne – and to a rote-based mode of teaching English still prevalent a century later in Japan. Structured according to the ‘Style of Sentence’, for example, Lesson 1 was entitled: ‘This is a book’. And Lesson 2: ‘This is a book and a pen’.Footnote 4

* * *

This is a story of how my privileging of the book and the pen led to my overlooking an archival bias inherent in any analysis of the Japan–Australia line’s history. As so often in the reconstruction of Australia’s colonial past, the written word led me to approach sources from a particular direction. What I mean by this will hopefully become clearer towards the end of the chapter. For now, it suffices to say that my archival work in 2013 began, as I assumed it logically should, with the records of the Sydney-based enterprise which served as the NYK’s managing agent for Australia after 1896. The papers of Burns, Philp & Co, incorporated in 1883, are today preserved in the Noel Butlin Archives Centre of the Australian National University in Canberra. And there, among ledgers and reports and correspondence, I came across a striking map, bigger when unfolded than an A2 sheet, with the title, ‘N. Y. K. Line: Map Showing the Routes and Ports of Call of N. Y. K. Steamers’ (see Map 1).

Map 1 ‘N. Y. K. Line’, c. 1923: Burns Philp Misc. Printed Material, N115/662.

The map depicted the Japanese archipelago, coloured in deep red, almost at the centre point of the folds. Though undated, the fact that Taiwan, Korea, southern Sakhalin and much of Micronesia were also coloured in deep red, thus indicating their status as Japanese colonies, suggested a publication date sometime in the mid 1920s.Footnote 5 From the imperial metropole, red lines fanned out across the maritime world. One thick line crossed the north Pacific to connect Yokohama with Seattle. Three more carved up the waters between Nagasaki and Shanghai before forking south-west to Hong Kong, where they divided: one continued through Southeast Asia and down to Australia, while the other threaded through the Indian Ocean, the Suez Canal, the Mediterranean and the Bay of Biscay, eventually to Antwerp, Middlesbrough and London.Footnote 6 The British Empire at its zenith – the oversized home islands, great swathes of East Africa, the Indian subcontinent, Australia and Canada – was coloured in pink, with much of the rest of the world in pale yellow.

The map was beguiling in its schematic simplicity. As perhaps to be expected, at one level it simplified the geopolitical realities of the contemporaneous mid 1920s.Footnote 7 Positing Japan as central to the Pacific world, its emboldened shipping routes seemed wilfully to cut across transpacific tensions over race and migration in the 1900s and 1910s, tensions which had provoked scaremongering books such as Must We Fight Japan? (1921) or restrictive anti-Asian legislation in the United States such as the Johnson–Reed Immigration Act (1924). Thus, the map’s red lines defied the early twentieth-century ‘white walls’ which settler societies in North America and Australia were erecting against the perceived ‘yellow peril’ from Asia in general and from Japan in particular.Footnote 8

At a second level, the map simplified the mid 1890s context in which the NYK’s new lines had originally been forged, including both Japan’s revised treaty of commerce with Britain (1894) and its victory in the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–5). The positive reading of this context was applied by Alexander Marks (1838–1919), honorary consul of Japan to Australia and later Victoria, who wrote to his Tokyo paymasters in March 1895: ‘The great prospects for the Nippon Yusen Kwaisha at the termination of the present war with their large fleet of steamers must naturally be of much commercial interest to Japan, and [to] her trading community.’Footnote 9 As the ‘N. Y. K. Line’ map confirmed, the company indeed opened three new prestigious routes in 1896 – to Seattle and to various European ports, as well as to Melbourne, thereby providing a stimulus to Japan’s international trading prospects.Footnote 10 But there was also a negative side to this story: on the docks and in the port-towns of Australia in particular, politicians and the press expressed fears about the arrival of Japanese and Chinese immigrants (as embodied by Hasegawa and his steerage companions), or of undocumented women from Japan (see Chapter 5). Thus, in exactly the years that the Yamashiro-maru steamed the Yokohama-Melbourne line, popular anxieties in Australia would culminate in the Federation of 1901 and the establishment of the new nation’s foundational ‘White Australia’ policy.Footnote 11

In other words, under the guise of cartographic objectivity the NYK map projected a number of claims about Japan’s position in the world, both in the mid 1920s but also stretching back to the mid 1890s. To critique each aspect of the map’s apparently neutral lines, points, colours and directionality is thus to unpack the propositions and conceptual schemata contained therein.Footnote 12 This I attempt in the chapter’s first two-thirds, where I use the Yamashiro-maru’s career in the period immediately prior to 1896 in order to demonstrate the very real military power which underpinned the map’s rhetorical power; and I then challenge the map’s representation of apparently frictionless hubs of Japanese–Australian connection by reconstructing the thick historical context in several ports at which the Yamashiro-maru called between 1896 and 1898.Footnote 13 My empirical base for this analysis was suggested by the map itself: where the lines met the land, be that in Brisbane or Sydney or especially in northern sites such as Queensland’s Port Douglas, I assumed that the tension between the NYK’s ‘great prospects’ and fears on the ground must have left some kind of archival trace. So it transpired, and there my work might have ended.

That it did not was due to my encountering the ‘Saltwater Visions’ temporary display at Sydney’s National Maritime Museum on the last day of my two-week research trip to Australia in November 2013.Footnote 14 This mini-exhibition centred on ten bark paintings composed by Yolŋu artists and activists in the north-east of Arnhem Land, in today’s Northern Territory. Five of the paintings, it was explained, had been used as evidence in a 2008 high court case which focused on the ‘ownership’ of coastal waters. In the years following that encounter, I began to realize that although the NYK map’s claims per se were important, the institutional settings in which those claims were preserved and could be researched must also be acknowledged. Those settings had framed not merely my knowledge of what I understood to be the ‘Japan–Australia line’ but also the positionality from which I approached its history: they were the museums, the university libraries, the state and national archives where I felt most at home, and even the infrastructures of digitization which had led me to a man such as Hasegawa Setsutarō. I explore these ideas in the section entitled ‘Archival Directionality’.

But an archive need not necessarily comprise books, words or maps, all to be measured for their empirical truths against other paper sources: for paper can simply be thrown away, as the Japanese historian Minoru Hokari learned from his mentor Jimmy Mangayarri of Daguragu.Footnote 15 Instead, ‘Saltwater Visions’ alerted me to something that my historical training in the universities of Britain and Japan had rarely allowed (in all senses of the word): that the material basis for historical claims need not only be paper and a pen. The sand could be the book; the bush, the university.Footnote 16 That is, the archive was as equally situated in Aboriginal country as in the modern state’s institutions of knowledge.Footnote 17 ‘Country’, as many scholars have pointed out, is a spatially fluid concept whose meanings may partly be read in contradistinction to the bordered sovereign entity of the colonial state (the etymological roots of ‘country’ lie in contra-).Footnote 18 Thus, if the earthy and watery materiality of the country could as equally be considered sites of archival knowledge as museums or university libraries, then the question arose: what counterclaims could be enunciated through this archive? I offer one answer to that question in the chapter’s final section.

As I say, I did not begin to imagine the archives in this way until my last day in Australia. My ‘stepping outside’ to that point had been less intellectually demanding, limited as it was to a two-day road trip to Queensland’s northernmost sugar-farming town of Mossman, where in 1898 a group of Japanese labourers arrived to work after their passage on the Yamashiro-maru to Port Douglas. Given these oversights, I planned in June 2020 to revisit the far north of Queensland – Mossman, Port Douglas and Thursday Island – in order to explore the basis by which historians might reconstruct alternative archival claims concerning the arrival of the ship and its passengers. The Covid-19 pandemic put paid to that trip, and in any case an additional two weeks would probably have been insufficient time to think through the lessons of Yolŋu saltwater visions for how the Kuku Yalanji peoples of Mossman might have understood the arrival of Japanese sugar labourers in their country in the late nineteenth century. Consequently, what follows in the chapter’s final third is less a reconstruction of the specific moment of the Yamashiro-maru’s arrival as seen from Kuku Yalanji perspectives than a broader challenge to the historical directionality both represented by the NYK map and embodied in the archival institutions of libraries, museums and universities. My argument here is for historians, as part of our archival practices, to acknowledge country-derived counterclaims to sources such as the NYK map as empirical interventions in our reconstructions of the past.

Claim 1: Lines Away from the Sinosphere

When a ship sailed, what did it carry? Goods and people, of course; but a ship also carried a set of associations which went beyond its cargo or physical appearance and crossed into the realm of the imagination. One entry point into this imaginative space was the ship’s name. It mattered, for example, that some functionary in the British Admiralty chose to rename the Earl of Pembroke, the Whitby-built collier that Captain Cook would command while observing the transit of Venus from Tahiti in 1769, the Endeavour. The ship could have as conceivably been called the Racehorse or the Carcass – both names, Nicholas Thomas quips, ‘which would rather have diminished the mythic potential of Cook’s voyage, one feels’.Footnote 19

So it was with the Yamashiro-maru: no records survive to indicate whether a KUK employee or an Imperial Navy bureaucrat chose the name for the 2,500-ton vessel launched from Low Walker yard 467 on a cold morning in January 1884 – but in Newcastle upon Tyne as elsewhere in late nineteenth-century Europe, an appellative strategy was clearly at work.Footnote 20 Yamashiro was the most important province of ancient Japan. The imperial capital had been moved there from Nara in 784 (that is, exactly 1,100 years before the Yamashiro-maru’s launch), and then again in 794 to another of Yamashiro’s settlements, Heian – later known as Kyoto, where the capital remained until the Meiji ‘restoration’ of 1868.Footnote 21 Meanwhile, the Yamashiro-maru’s sister ship, the Omi-maru, was named after a neighbouring province and site of one of the ancient court’s summer palaces (Ōmi 近江), while the fourteen other British-built steamships of the KUK fleet each carried province- or place-names that connoted Japan’s seventh-century Ritsuryō state.

Such referencing of the distant past for the transformative present was standard fare in mid–late Meiji Japan, as demonstrated by the rhetoric of the 1868 revolution as a ‘revival of ancient kingly rule’ (ōsei fukko 王政復古). Modern innovations were regularly embellished in the language and iconography of the ancient, as in (to name but one of countless examples) the new paper notes of the new national currency, which were released in 1873 and whose ten-yen issue featured the legendary Empress Jingū (169–269 CE) on her conquest of the Korean peninsula.Footnote 22 In many cases, moreover, such uses of the past also had spatial and not merely temporal dimensions. In 1869, Meiji officials renamed the large island to the north of Honshu from Ezo to Hokkaidō (北海道), literally ‘northern sea circuit’. This looked back to a spatial ordering of the aforementioned Ritsuryō state known as the ‘five provinces, seven circuits’ (goki-shichidō 五畿七道) – except that Hokkaido now implied an eighth circuit, as if the island had been part of a Japanese territorial imagination from time immemorial.Footnote 23

A ship named Yamashiro, after one of those five central provinces, therefore made explicit reference to the spatial logic of ancient Japan. Indeed, in cartographic terms it recalled a schematic type of provincial map, used even into the nineteenth century, in which Yamashiro was marked as the ‘centre of the imperium’ and distances were indicated in the time it took to travel ‘up’ to the imperial capital and back ‘down’ – that is, to and from Kyoto.Footnote 24 Such temporal schemata were a far cry from the mid-1920s ‘N. Y. K. Line’ map, which offered a representation of space apparently divorced from time, with Japan rather than Kyoto at its folded centre. But as the infrastructures were put in place from the mid 1880s onwards to realize this NYK vision of Japan’s place in the maritime world, the Yamashiro-maru’s early status as the fleet’s primus inter pares made the ship symbolically central to mid-Meiji Japan in a way presumably intended to reference the historical province’s analogous centrality to the ancient state. In this sense, to adapt Kären Wigen’s apt phrase, the ship constituted a ‘province of the mind’.Footnote 25

In fact, however, the NYK map can also be read through a temporal lens. As we have seen, the bold red lines emanating from Japan glossed over the geopolitical realities of the 1920s, namely that white walls had been or were being erected in the Pacific Anglosphere to keep Japanese immigrants out. Yet such contestations notwithstanding, the drawing of thick connections across the Pacific was itself indicative of a major historical transformation. Throughout the Tokugawa period, Japanese world maps had presented an ocean untraversed by shipping lines. Moreover, in Nagakubo Sekisui’s (1717–1801) famous ‘Complete Illustration of the Globe, All the Countries, and the Mountains and Oceans of the Earth’ (c. 1790), the great uncoloured space at the centre of the world was not even marked the ‘Pacific’ (see Map 2). It was instead labelled both the ‘small eastern sea’ and the ‘large eastern sea’, in which ‘small’ (it has been argued) suggested nearby or familiar and ‘large’ faraway or fearful, thereby reflecting a profound Japanese ambivalence towards the distant Pacific world before the mid nineteenth century.Footnote 26 By contrast, Nagakubo’s colour scheme, whereby all of South, Southeast and East Asia (including Japan) were marked in red, unambiguously posited Japan as part of the continental Sinosphere – a positioning reinforced by the fact that the cartographic inspiration for Nagakubo’s map had been published in Beijing in 1602 and entered Nagasaki, via Jesuit conduits, soon thereafter.Footnote 27

Map 2 Nagakubo Sekisui, ‘Complete Illustration of the Globe, All the Countries, and the Mountains and Oceans of the Earth’ (Chikyū bankoku sankai yochi zenzusetsu 地球萬國山海輿地全圖説), c. 1790. Call number G3201 .C1 1790z N2.

This contrast in representations of Asia and the Pacific reveals that the claim in the NYK map was not simply for Japan’s post-1868 centrality to the Pacific world; it was therein also a claim against the hitherto defining role that the Sinosphere had played in Japanese cultural and intellectual life for many centuries.Footnote 28 In the map’s colour scheme, imperial Japan’s deep red now stood in marked contrast to China and Mongolia’s yellow. Even the graticule delineation of longitude and latitude reinforced the map’s message of new world centres away from China, with zero degrees longitude anchored at the Greenwich meridian.Footnote 29

Steaming towards Australia in October 1896 and thereby establishing one of the subsequent NYK map’s linear claims, the Yamashiro-maru was emblematic of Japan’s transformed temporal relationship to the Sinosphere. On the one hand, the ship’s name referenced the Ritsuryō state, itself modelled closely on Tang China (618–907). On the other, after being requisitioned by the Japanese Imperial Navy in June 1894, the ship had been active in the conflict which brought China’s long claim to wider cultural and intellectual influence in East Asia decisively to an end, namely the Sino-Japanese War (1894–5).Footnote 30 True, the Yamashiro-maru was never feted for its wartime service in the Japanese press like its NYK counterpart, the Saikyo-maru, which famously fought in the heat of the Battle of the Yalu River.Footnote 31 Rather, from July 1894 to the end of the war in April 1895 and even into the first months of peace, the Yamashiro-maru’s role was to deliver torpedoes to the imperial navy’s battleships, and to supply coal to those ships as they were engaged across the Yellow Sea (see Map 3). But such logistical support from the NYK commercial fleet was nevertheless vital in bringing to fruition Fukuzawa Yukichi’s desire for Japan to ‘cast off Asia’.Footnote 32

Map 3 ‘Chart of the Mother-Ship Yamashiro-maru’s Routes’ (Bokan Yamashiro-maru kōseki ryakuzu 母艦山城丸航跡略図), 1894–5.

Thus, while the Yamashiro-maru’s name conjured up a seventh-century imagination of spatial order in Japan and in East Asia, its Australia-bound navigations looked to a post-Sinosphere future and to a new cartographic representation of Japan’s place in the world. That the ‘great prospects’ for this new route had been enhanced by victory in the Sino-Japanese War – that the Yamashiro-maru’s service to the southern hemisphere was inseparable from its supply missions in the Yellow Sea – reminds historians of two oft-overlooked truisms: first, that conflict was a key form of connection in the modern world; and second, that the power of maps ultimately derives from the force – legal, bureaucratic and in this case military – which lies behind their representation.Footnote 33

These were just some of the ideas borne by the Yamashiro-maru in 1896. And while no Australian newspaper could have been expected to know the finer details of the ship’s career or its historical references, NYK company officials and Meiji bureaucrats would nonetheless have purred at some of the press coverage triggered by the Yamashiro-maru’s arrival. The Melbourne Argus remarked upon the ship’s ‘exciting exploits’ during ‘the late war between China and Japan, in which she acquitted herself with credit’; the Rockhampton Morning Bulletin (Queensland) alleged that due to the ship’s design, the ‘peaceful trader’ could in merely twenty minutes metamorphose into a ‘virulent wasp of war’.Footnote 34 But of especial note were the Morning Bulletin’s opening sentences, which offered a volley of pleasing tropes – Japan’s ‘aptitude’, its ‘spirit of progress’ and ‘intellectual powers’ – like a cruiser firing a salute:

Japan is the coming nation. Since it doubled up the Chinese forces and fleets in the late war it has been praised and admired by the western nations. Not so much a revival of something that had formerly been in active existence, but a great demonstration of the possession of intellectual powers and capabilities, and manifestation of a spirit of progress have raised it to a prominent place among the powers of the earth. Among other things it is displaying an aptitude and a desire for engaging in trade and commerce. Of this we have had practical evidence by the appearance on the Queensland coast of the pioneer steamer of the Nippon Yusen Company.

Claim 2: Points of Contact

If the first of the NYK map’s claims lay in its delineation of ‘routes’, then its second lay in its representation of ‘ports of call’: that is, of precise points where the lines met the land. The ships docked, business was conducted and then the ships moved on – or so the map’s reader is led to believe.

In my case, the simple clarity of this representation was bolstered by the archival port of call I had made in the early pre-fieldwork stages of my Australian research, namely to the National Library of Australia’s database of historic newspapers. There, a basic search with the keyword ‘Yamashiro’ for the year 1896 had uncovered such gems as the Rockhampton Morning Bulletin’s characterization of Japan as ‘the coming nation’. More broadly, it had revealed a genre of article which had been generated from a particular place: not the dock (which I’ll return to shortly) but rather the ship’s saloon. For when the Yamashiro-maru called at port, this ‘handsome apartment’ in the vessel’s stern, most probably lit by small chandeliers and filled with a long dining table at its centre, itself became a port of call: for local businessmen, politicians and newspapermen, who gathered to laud and report on the ship’s arrival.Footnote 35 We can join them in Brisbane on the summer evening of 3 November 1896, an auspicious day, when, ‘it being the Japanese Emperor’s birthday[,] the ship was going dressed with all her bunting, which attracted great attention’ in the city.Footnote 36 Captain James Jones has invited more than twenty local dignitaries to dinner. Glasses tinkle, cutlery clinks, men’s voices rise, the sun sets – and then a hush descends upon the ‘commodious and airy’ saloon.Footnote 37

The first to speak is the Honourable Thomas J. Byrnes (1860–98), attorney-general of Queensland. Dark hair brushed high on his forehead, Byrnes is a precocious young man, his fulsome beard giving him an older appearance than his thirty-six years. His erudition in history and his skills as a barrister make public speaking second nature, and his three years to date as a legislative assemblyman for Cairns mark what will be his rapid ascent to the colony’s premiership by 1898.Footnote 38 We do not know Byrnes’s direct words, only – from the paraphrasing of the Brisbane Courier’s correspondent – that he celebrates the Yamashiro-maru’s arrival as the first time a steamer flying the Japanese mercantile flag has come up the Brisbane River. ‘It [is] a fine thing for Queensland to have direct communication with rising Japan,’ he says of the new NYK line, and indeed inevitable that ‘the Eastern countries’ would seek new markets for their commercial enterprise. On the occasion of the emperor’s birthday, and ‘looking at things from the broad standpoint of progressive humanity’, Byrnes suggests that they (the Japanese? the assembled gentlemen?) ‘ought to be proud of the strides made by the Japanese nation, and he trusted the Emperor would be spared to see his people make still further advancement.’Footnote 39

The speeches continue: Captain Jones on behalf of the Nippon Yūsen Company; Mr Thynne, postmaster general, proposing a toast to the NYK’s Queensland agents, Burns, Philp & Co. (in whose archives I found the map); Mr Robert Philp (1851–1922), responding on their behalf, but also present as Queensland minister for railways and mines; and various other toasts, including to ‘The Health of the Queensland Ministry’ and ‘Long Life to the Mikado’.Footnote 40 Indeed, it was the same story as the Yamashiro-maru steamed southwards: celebratory luncheons in Sydney and Melbourne; newspapers commenting on how ‘the inauguration of a new and well-subsidised mail service with a distant country is felt to be an event in a nation’s history’; more onboard toasts as the ship returned northwards; and all this couched in the trope of the Yamashiro-maru as a ‘pioneer’ steamer – a word redolent with meaning in a white settler society.Footnote 41

What was the ‘commercial enterprise’ that Byrnes and others had in mind? On the Yamashiro-maru’s maiden voyage to Australia, the ship carried a cargo which included fish oil, bamboo blinds, camphor, curios, matting, silk, rice and fire crackers.Footnote 42 The last item excepted, this was not a list of goods likely to ignite an immediate boom in bilateral trade. Instead, the Kobe-based Kanematsu Shōten (Kanematsu Trading Company), which from 1890 had been the leading Japanese company involved in the Australia trade, was merely exploring what shape the future Japanese export market might take.Footnote 43 For, as Captain Jones explained in a lengthy interview with the Daily Telegraph (Sydney), ‘[The Japanese] say they have not found out yet exactly what the Australian people will purchase from them, but they are making inquiries on this subject, and hope in time to get in touch with the Australian markets.’Footnote 44

More likely, then, Byrnes and company were excited about the Japanese market for Australian goods. Already in December 1896, the Yamashiro-maru returned to Japan with a cargo including 500 bags of crushed cattle bone, plus more bones, sinews and hooves – in other words, the raw materials of fertilizer for the Japanese agricultural sector. By one of the Yamashiro-maru’s final return trips, leaving Australia in August 1898, the ship’s cargo included more than 500 tons of fertilizer, plus 1,031 bags of bones, hooves and other component parts of bonemeal. To be sure, 1898 was an exceptional year: processed fertilizer accounted for more than 40 per cent of the total value of Australian imports to Japan, whereas during the first fifteen years of bilateral trade, the most important cargo by value was generally sheep’s wool.Footnote 45 (As Captain Jones also explained to the Telegraph, ‘The Japanese, whose clothing has hitherto been cotton, imported from India, are taking to wearing wool.’)

Either way, the export of wool and fertilizer from Australia to Japan placed this new trading relationship at the heart of a wider ecological transformation of the Pacific world. In Japan, German-trained soil experts in the mid 1890s had calculated that the archipelago had a serious phosphate deficit: the search was on for new sources of agricultural fertilizer, including both guano deposits and domestic bonemeal. The import of Australian bonemeal was thus one element of a wider concern for Japanese phosphate production, a concern which led both to the entrepreneurial exploitation of islands in the western Pacific and to the large-scale import of soybean cake from Manchuria.Footnote 46 Moreover, as Gregory Cushman has argued, the fact that nineteenth-century colonialists had successfully turned much of Australia into – in terms of livestock production – a ‘mirror image’ of the British Isles was itself a development dependent on fertilizer, and thus on the destruction of several tropical islands in the Pacific in the name of guano imports.Footnote 47

The advent of the Japanese mercantile flag coming up the Brisbane River and trading in cow and sheep products was therefore a story of the Australian colonies’ own economic engagement with and exploitation of the Pacific Ocean. This may explain the expansionist vision expounded by saloon speakers at the Yamashiro-maru’s other ports of call. In Sydney, for example, Mr James Burns, managing director of Burns, Philp & Co, declared that his city ‘was destined to become the London of the southern seas’. There were good prospects for direct services from Sydney to Manila, Dutch Java, German New Guinea and beyond. ‘Altogether, everything pointed to expansion. Sydney, from its natural position, should command the whole of the trade of Greater Australia, embracing the rich and fertile groups of islands that stretched from our shores to China and Japan, and east to North and South America.’Footnote 48 By this logic, the NYK’s lines from Japan to Australia were just part of a story in which Sydney would be connected to other strategic points in the Pacific world. This was an outward-looking imagination of ‘Greater Australia’ (itself a term which perhaps drew on contemporaneous Anglophone discourses of Greater Britain or Greater America) – as if ports, being departure points for exports, were sites primed towards the sea and not the land. Perhaps Burns’s views were momentarily shaped by their articulation in the extraterritorial space of the ship.

Even in the saloon, however, inward-looking anxieties wisped among the invitees. They were to be sensed in the denials. Queensland Attorney-General Byrnes: ‘He did not view the new [Japanese trading] venture with apprehension at all, but a needless amount of alarm had been expressed about it. He believed the Anglo-Saxon race would hold its own.’ Mr Philp: ‘He was not afraid of the Japanese coming to Australia and flooding them out. […] He did not think there was the slightest fear that the Japanese would come here in greater numbers than Queensland would care to receive.’Footnote 49 And in Sydney, the former premier of New South Wales, Sir George Dibbs (1834–1904): ‘Australians were not afraid of the Japanese.’Footnote 50

And yet, as these keen politicians knew, many Australians felt differently. In Brisbane, the Worker newspaper had for the past three years warned of a ‘Jap deluge’, of ‘A Plague of Japs’, of ‘JAPANESE DANGER’ (this in a letter from an enraged ‘Anglo-Saxon’), and of ‘Japs Colonising Queensland’.Footnote 51 The assembled gentlemen could hardly have been surprised, therefore, by the Worker’s visual representation of the Yamashiro-maru’s arrival, a few days after the celebratory onboard dinner (see Figure 4.1). Under the headline, ‘AUSTRALIANS, HOLD YOUR OWN!’ (itself a phrase used by Byrnes), a cartoon depicted a large steamship, its Rising Sun flag fluttering in the breeze as its cargo is manifested on the quayside. The ship is a hive of activity: an officer stands on a soapbox directing operations as two Asian-looking men manoeuvre a large crate marked MACHINERY; behind them appear other boxes and containers, all labelled with a popular nickname referring to Sir Thomas McIlwraith (1835–1900), the former premier of Queensland and leading figure in the colony’s politics.Footnote 52 Meanwhile, in the cartoon’s foreground an East Asian sailor grapples with a swarthy Caucasian worker, wrapping his claw-like hands around the worker’s throat. All this is observed by a multitude of unemployed men – IRON FOUNDER, BOOT MAKER, [C]ARPENTE[R] – whose numbers press back into one of two large warehouses on the dock.

Figure 4.1 ‘AUSTRALIANS, HOLD YOUR OWN!’ Worker: Monthly Journal of the Associated Workers of Queensland (Brisbane), 7 November 1896.

As the Worker’s title made clear, the newspaper’s particular gripe was with the perceived threat of cheap Japanese labour, which would allegedly undercut the working man’s wages and even render him unemployed. Here, the dock rather than the saloon was the key point of contact between the ship and the shore, and the antagonism expressed in the Worker’s 1896 cartoon therefore belied the NYK map’s later representation of lines cleanly intersecting with the land. Indeed, the New South Wales politician and secretary of the Sydney Wharf Labourers’ Union in the late 1890s, William ‘Billy’ Hughes (1862–1952), made anti-Asian labour campaigns central to his emerging career. Two decades later, as Nationalist Party prime minister of Australia, Hughes and US president Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924) agreed to deny Japan’s campaign for a ‘racial equality’ clause at the Paris Peace Conference – thereby undermining the NYK map’s fiction of untrammelled transpacific connections.Footnote 53

Perhaps most striking of all, the anxieties present in the Yamashiro-maru’s saloon were revealed by the disconnect between the private celebrations of politicians who supped at the NYK’s expense, and their statements of a very different tenor for the official public record. In Queensland, for example, the Legislative Assembly had first debated the issue of Japanese immigration in June 1893, partly prompted by a brief report in the Sydney Daily Telegraph to the effect that 500 Japanese labourers had recently arrived to work in the northern Queensland sugar plantations.Footnote 54 Thereafter, in increasingly heated annual debates on the issue, politicians of all persuasions – even those, such as Byrnes, who argued that the solution to immigration concerns was to increase the number of white immigrants to Queensland rather than worrying about the Japanese – used the language of ‘invasion’ to describe the alleged problem. This drew on a longer discourse both in the colonies and in the British metropole concerning the numerous perceived threats from Russia, China or latterly Japan – or a combination of all three. In Australia it found particular expression in the popular literature of the time, such as the 1895 novel by New South Wales-born Kenneth Mackay (1859–1935), entitled, The Yellow Wave: A Romance of the Asiatic Invasion of Australia.Footnote 55

Indeed, as if prompted by the language of ‘waves’, many Queensland assemblymen also drew on metaphors of water. In the first debate on Japanese immigration, one spoke about ‘the new importation [of Japanese] with which we are about to be deluged’ (the Worker had used the same term three months earlier).Footnote 56 Albert James Callan (1839–1912), member for the constituency of Fitzroy and invitee to the Yamashiro-maru in November 1896, announced the danger that ‘this country, and especially the Northern portion of it, will be inundated with Japanese’. In 1897, he suggested that ‘one of the most grievous dangers Queensland has to face is the possibility of an influx of Japanese’ – a word used almost as frequently as ‘invasion’.Footnote 57 Such was the power of the water metaphor that Robert Philp, whose business interests were so entwined with the NYK, was forced to deny in his onboard speech the prospect of ‘the Japanese coming to Australia and flooding them out’.Footnote 58

Thus, at the very point where the line met the land, be that the saloon or the dock, anxieties about labour and race threatened to muddy the vision of an outward-facing Australia and an expansive Japan connected across the seas. The latter was an optimistic vision which would later justify the cartographic claims of the ‘N. Y. K. Line’ map in the mid 1920s. But, as suggested by the language of inundation, flooding and tides, it was also an inherently unstable imagination of the world.Footnote 59 Such instabilities were particularly pertinent for the cargo unmentioned in the ‘Ex Yamashiro Maru’ lists of goods and wares, namely the Japanese men and small numbers of women who travelled on the NYK ships – migrants who were largely poorer and less educated than Hasegawa Setsutarō. As we shall see, for Japanese male labourers disembarking in the far north of Queensland as for white working-class readers of the Worker in Brisbane, blots rather than clean points would have been a more realistic graphic by which to represent Japanese–Australian entanglements.Footnote 60

Claim 3: Uniform Colours

Though Japan may well have been ‘the coming nation’ for the Rockhampton Morning Bulletin in November 1896, it was not the only one. In fact, the exact same phrase had been used in the Queensland Legislative Assembly’s first debate on Japanese immigration in June 1893 – but with reference to Australia. ‘In the name of the coming nation,’ exclaimed John Dunsford (1855–1905) at the end of his speech, ‘I call upon the Premier and this House to assist in making this a white man’s country, and [in] conserving the welfare of the coming Australian nation.’Footnote 61

The NYK map’s colour scheme was problematic for the monochrome claims of uniformity it made about this alleged white man’s country.Footnote 62 At a first level, these claims were a question of the implied umbilical cord between Britain and its Australian dominions (both coloured the same shade of pink). In fact, that cord had been under increased strain since July 1894, when Britain led the world in concluding a new Treaty of Commerce and Navigation with Japan, thereby replacing the 1858 ‘unequal’ treaty (see Chapter 6). The new agreement, to come into force in 1899, included the promise of ‘full liberty’ for both Japanese and British subjects ‘to enter, travel, or reside in any part of the dominions and possessions of the other Contracting Party’ (Article I). That is, Japanese people would be free to live and work in the dominions of Australia – if, within a two year period, the Australian colonies agreed to adhere to the treaty’s provisions. But if they did not agree, then the colonies would equally not enjoy ‘the reciprocal freedom of commerce and navigation’ between the contracting parties (Article III), including protection from unequal import tariffs (Articles V and VI) and the mutual right to transport goods to port without depending on each other’s merchant navies (Articles VIII and IX). In these ways, the treaty was central to the vision of an expansive, Pacific-facing Australia articulated on the Yamashiro-maru by James Burns, with Sydney as the ‘London of the southern seas’. And yet, as the Queensland premier confidentially telegrammed his Victoria counterpart in April 1895, ‘it may be found necessary to legislate for restriction of [Japanese] immigration into Queensland in which case adhesion to Treaty would cause difficulty at the time such legislation was initiated’.Footnote 63

The dilemma that the British–Japanese treaty thus forced upon the Australian colonies, between the promise of free trade and the peril of free entry, was epitomized in Queensland by the contradictory voices emerging from Rockhampton. As we have seen, the town’s newspaper lauded the opening of the new NYK line in November 1896, including Japan’s ‘desire for engaging in trade and commerce’. Twelve months earlier, however, the Rockhampton Chamber of Commerce had also passed a resolution arguing that ‘it will be very injudicious for these Colonies to accept the Imperial Commercial Treaty with Japan of 1894 and thereby grant a free and unrestricted entry of the Japanese into this and the adjoining colonies’. In case the message was unclear, the Chamber’s secretary explained to the Queensland premier that the treaty ‘carries with it the very objectionable risk of flooding our country with an undesirable alien race’.Footnote 64

If anything, the arrival of the Yamashiro-maru in 1896, at a time when the colonies’ adherence or otherwise to the treaty was still an open question, was therefore a reminder of Australia’s relative impotence concerning its relations to Asia’s coming nation. As the aforementioned honorary consul of Japan, Alexander Marks, provocatively noted in his saloon speech upon the ship’s arrival in Melbourne, ‘[t]he Governments of Australia should understand that they were parts of the British Empire. Britain had made treaties with foreign nations, and those treaties must be observed. Of course Australia had no “sovereign rights”.’Footnote 65 Others were less sanguine about this reality. A month earlier, an editorial in the Maitland Weekly Mercury (New South Wales) obliquely referenced Cinderella when it complained:

Our right of self-government is a mockery, unless it includes power to regulate the components of our population. […] And, if we are threatened with a gradual, an insidious, but none the less certain and menacing irruption of [Chinese, Japanese] and other peoples whom we do not desire for the purposes of admixture with our own, the mother-country must help us. She must see that it is an essential part of Imperial policy that she should help us. She is no mother at all, but only a cruel stepdame, if she does not.Footnote 66

As for Queensland, by the time of the Legislative Assembly’s 1897 debate on the ‘Continued Immigration of Japanese’, the metaphors connoted less pantomime than power abuse, with one member objecting ‘to the British Government practically holding up a revolver to our heads’. Hence the proposal, in Queensland and elsewhere, that if ‘[w]e are all agreed that the Japanese should not be allowed to flow into this colony’, then ‘[t]he great remedy is for Australia to become united under one Federal Government.’ Or, as the Rockhampton representative phrased it, ‘I have no more desire to cut the bonds that bind us to the old country than the [previous speaker] has, but if the only way by which I could save Australia from an Asiatic invasion was by cutting those bonds I would do it to-morrow.’Footnote 67

In portraying the Australian continent as a single political entity in the mid 1920s, the NYK map sanitized a history of excision between the ‘old’ or ‘mother’ country and the colonies. In fact, the perception of a Japanese influx had been one stimulation for the federated Australia that the map now depicted, an act of fundamental disconnection from Britain. At this first level, therefore, the conformity of pink across the map’s British empire offered a rose-tinted interpretation of metropole–colony relations during the period of the new NYK line to Australia.

The second way in which the map’s colours corralled the colonies’ recent past was in their conformity of pink across the huge area of Queensland – as if political control was evenly distributed from Brisbane, in the south, to Thursday Island, more than 2,000 kilometres to the north (comparable to the distance between London and Saint Petersburg). In the eyes of Australia’s late nineteenth-century opinion makers, such control was more de jure than de facto. Editorializing on the new British-Japanese treaty, the Sydney Morning Herald argued that Australia’s relations with Japan must be considered differently from those of England, America and the nations of Europe, for ‘[n]o other has vast unoccupied territories exposed to an influx of people’. Australia’s choice, the paper claimed, ‘will have to be taken between exclusion from a share in the coming trade of Japan and the possibility of our unoccupied territories being overrun by an alien “inferior race”’.Footnote 68 In other words, the colonies’ legal claim to ‘territory’ was undermined in practice by the fact that so much of Australia was allegedly ‘unoccupied’.

In the case of Queensland, this tension found expression in the trope of the ‘empty North’, and one site at which its contours were rendered visible was the small town of Mossman, some 1,500 kilometres north of Brisbane.Footnote 69 In the mid 1890s, Mossman was the northernmost outpost of the Australian sugar industry, as it remains today. But Mossman had never been unoccupied. The wide river valley was, and is, known as Wikal. Manjal Dimbi, at the valley’s western rim, is the ‘mountain holding back’, representing in turn Kubirri, the ‘good shepherd’ who restrains the flesh eater, Wurrumbu, and thereby protects the people.Footnote 70 And the people, speaking Kuku Yalanji, had lived off this land for many thousands of years before European gold prospectors and loggers began to encroach in the early 1870s and impose their own placenames.

Among the arrivistes was a certain Daniel Hart, who described himself as a British subject and ‘native of the West Indies’. This presumably made him familiar with the Caribbean sugarcane economy, and indeed in an 1884 petition to the governor of Queensland, Hart described an exploration he undertook in June 1874 from Cooktown to the area around the Mossman River, where he and his small party discovered an ‘abundance of cedar and excellent sugar land’. Hart reiterated how his own subsequent clearances and the arrival of other loggers fully endorsed ‘his repeatedly expressed opinion as to [the land’s] value for sugar growing’. (In the petition, Kuku Yalanji people appear only offstage, when Hart mentions that two men from another party ‘were speared and conveyed to hospital by Your Petitioner’.)Footnote 71

But the gap between Hart’s sugarcane vision and the reality on the ground was substantial. At the very least, the land must be cleared, a mill built, the cane cultivated, and the crop harvested at speed – that is, transported to the mill for juice extraction and purification in the forty-eight hour window before the cut cane would begin to rot. All this required capital and labour. Further south in Queensland, where the sugar industry had been developed since the mid 1860s, the labour had been provided partly by Chinese immigrants who had previously crossed to Australia in successive gold rushes, and partly by Pacific Islanders, whom the white settlers derogatorily referred to as ‘kanakas’ – that is, labourers often transported to Australia against their will and in horrific conditions.Footnote 72 (A key motivation for one of the Yamashiro-maru’s first captains, John J. Mahlmann, to pen his later autobiography was to deny his involvement in this ‘blackbirding’ trade in the late 1860s: see Chapter 1.) But such was the weight of liberal opinion against the importation of Pacific Islanders that legislation banning the trade was passed in 1885 – just as Hart was imagining a sugar future in the Mossman River valley. Though not effective immediately, both the ban and simultaneous restrictions on Chinese immigration were two factors, along with a decline in sugar prices, which resulted in the contraction of the Queensland sugar industry in the late 1880s.Footnote 73

That a newly constructed mill was nonetheless to be found in Mossman less than a decade later was due in no small part to the Queensland government’s attempts simultaneously to stimulate the sugar industry, to encourage white settlement in the colony, and thereby to fill the ‘empty North’. One legislative mechanism to do so was the Sugar Works Guarantee Act (1893), by which public loans were pledged to finance the construction of expensive sugar mills. This, it was hoped, would increase the financial viability of small, family-managed sugar farms – which would in turn attract white settlers as far north as places like Mossman.Footnote 74 (In this way, the Queensland sugar model was very different to that of Hawai‘i, where mills were privately owned and required major investment, leading to the consolidation of the industry in the hands of major capitalists.) Under the Act, therefore, a group of settler-farmers formed the Mossman Central Mill Company in December 1894 and borrowed £66,300. The mill crushed its first cane in August 1897, and within a decade had almost quadrupled its tonnage. In a 1904 newspaper report, it was considered ‘to be in a good position financially’.Footnote 75

So much for the problem of capital. But the problem of labour remained, despite the presence of several hundred Chinese and Pacific Island workers in the Mossman district.Footnote 76 And this labour shortage explains the arrival of 100 Japanese men at Port Douglas on the afternoon of 12 August 1898 – labourers who were contracted to work at the Mossman Central Mill Company.Footnote 77

The men who stepped off the Yamashiro-maru that afternoon knew none of this context. Like their compatriots in Hawai‘i, they had left Japan in search of better wages and perhaps the possibility of a new life. Like Wakamiya Yaichi and Kodama Keijirō, they hailed from Hiroshima and Kumamoto prefectures respectively; indeed, sixteen of their number came from Hiroshima’s Saeki county alone (see Chapter 2).Footnote 78 There was, however, one structural difference with their migration from that of their earlier Hawaiian counterparts: the Mossman men travelled under the auspices not of the state but rather through the mediation of a private emigration enterprise, the Tōyō Imin Gōshi Gaisha (Oriental Emigration Company). Co-founded under a different name in 1891 by a Tokyo businessman and the vice-president of the NYK, the Oriental Emigration Company shipped more than 10,000 Japanese overseas in the period 1891–1917, including to New Caledonia, Fiji, Guadeloupe and Brazil. Along with dozens of other private migration companies which were founded in the years after the replacement of the Hawaiian government-sponsored programme in 1894 by a system of ‘free’ emigration, the Oriental Emigration Company thereby contributed significantly to an expansive vision of the Japanese empire articulated in the mid 1890s by a coalition of Tokyo-based politicians, journalists, intellectuals and businessmen.Footnote 79 The Mossman Japanese were the foot soldiers of this transpacific vision – though this, too, they were not to know.

Although this imagination of a ‘Greater Japan’ (Dai-Nihon) had many ideological reference points, one of its key tenets was a Malthus-inspired discourse of domestic demographic explosion – and, so the thinking went, a concomitant need to identify overseas destinations for Japan’s surplus population.Footnote 80 And although Queensland’s politicians were far from attuned to the nuances of the Japanese-language debates in Tokyo, population considerations were also central to their anti-treaty (and anti-Japanese) rhetoric. Thus, against the ‘scattered population of North Queensland’ was contrasted ‘the teeming population of Asiatic countries that are close within reach of our ports’.Footnote 81 The aforementioned Mr Callan was typical in his articulation of the problem, in August 1895:

You cannot bounce the Japanese. They have had their turn at war now, and have done remarkably well, and if they once turn their attention to Queensland, I do not know that there is anyone here capable of keeping them out unless measures for the purpose have been taken beforehand. It is ridiculous to talk about stopping the Japanese without England to back us. We [Queensland] have a population of about 400,000, or about the population of a third or fourth class European city, and Japan has a population of 40,000,000. What could we do unless we put the case before those who are able to protect us, and say we do not want the Japanese to come here?Footnote 82

Yet by the winter months of mid 1898, Queensland’s range of possible ‘measures’ had narrowed considerably. Having joined the 1894 Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation on the expectation that a separate protocol on the immigration of labourers and artisans, agreed in March 1897 with Tokyo, would also be accepted by London, Brisbane’s politicians were dismayed to be disabused of that notion by the mother country in August 1897.Footnote 83 (This was the context for the ‘revolver’ complaint.) A year later, as ships continued to discharge Japanese men and women at Thursday Island in their dozens, the Townsville Daily Bulletin furiously observed that ‘this peaceful invasion will prove so disastrous to Queensland’s interests ultimately that Thursday Island will be in fact an “appanage of the Mikado’s kingdom”’.Footnote 84 And thus, in the absence of legislative options, the new premier of Queensland, Thomas J. Byrnes (who had led the celebratory speeches onboard the Yamashiro-maru in November 1896), decided to strengthen the administration of immigration control, by decreeing that any Japanese without valid passports for Queensland would not be permitted to land in the colony. In the meantime, however, the Yamashiro-maru had already left Japan for Australia, carrying among its passengers the 100 Mossman-bound labourers – and thus prompting a flurry of telegraphs between various agencies about the legal status of those on board.Footnote 85

These were the circumstances in which the Mossman Japanese disembarked in Port Douglas in August 1898: a diplomatic wrangle over passports – a wrangle itself reflective of wider geopolitical tensions over the position of the Australian colonies in Britain’s new relationship with Japan – tensions themselves prompted by anxieties about the ‘scattered’ settler population in the otherwise ‘unoccupied’ North – anxieties themselves suggestive of the concomitant need to encourage further Anglo-Saxon colonization through state subsidies for the emerging sugar industry. If the labourers detected a chill in the air, it had nothing to do with the winters, which are mild this far north. Instead, it had to do with the ‘public feeling’ in Port Douglas that ‘runs very high against the importation of Japanese’.Footnote 86 And it had to do with the accusation that the contracting of Japanese to work at Mossman ran against the intent of the 1893 Sugar Works Guarantee Act – as articulated by the Rockhampton-based Capricornian newspaper:

When the central mills scheme was launched by the Government, and Parliament agreed to invest such a large sum in the venture, the great inducement held out was that by this means black labour would be shut out of the colony, and at the same time the sugar industry would be saved from destruction. But now the Government which put forward this argument is itself sanctioning the introduction of Japanese for one of these very central mills, built by Government money for the purpose of establishing the sugar industry on a white instead of a black man’s basis.Footnote 87

In this Manichean world view, the Queensland sugar industry was strategically important not just for its economic value but because, through the provision of central mills, ‘black labour would be shut out of the colony’. In this way, ‘white sugar’ was not just a descriptor of the end product but also an aspirational marker of the labour involved in its production. Conversely, any labourer who was not white – be they ‘black’ or Japanese – contaminated this vision of white product and white production.Footnote 88 To complain about the ‘introduction of Japanese’ in Mossman was another way of calling the Japanese racially impure: their presence in the mill would undermine the coming nation’s imagination of its own refined future.

Thus, at the point of Port Douglas, where 100 Japanese disembarked from the new NYK line, the colonial polity imagined by Brisbane politicians could never merely be a colour on the map: it was also a question of the colour of skin and the colour of the product, and thus a question of who would be free to enter and who would be shut out.Footnote 89

Archival Directionality

One of the most detailed surveys of the northern Queensland sugar industry at the turn of the twentieth century survives not in Brisbane, Sydney or Canberra but in Tokyo. Written by Townsville consul Iijima Kametarō on the basis of a three-week tour he took in July and August 1900, the ninety-one-page handwritten report describes the location, labour force, acreage, working conditions and production output of the planting districts at – travelling north from Townsville – Macknade, Ripple Creek, Victoria, Goondi, Mourilyan, Hambledon and Mossman; and, just to the south of Townsville, Kalamia and Pioneer (see Figure 4.2). This itinerary was determined by the distribution of Japanese sugar labourers throughout the northern part of the colony, ranging from the 57 employed at Ripple Creek to the 137 working at Victoria, and numbering 839 in all. At Mossman, Iijima wrote of only 70 Japanese labourers – not two years after 100 had arrived on three-and-a-half year contracts. The reason for this was that in March 1900 (he explained), the Japanese there had gone on strike. Broken only after the intervention of the Townsville consulate, one result of the unfortunate incident was that the main instigators were repatriated to Japan.Footnote 90 Iijima was suitably vague on this point, but contemporary newspaper reports suggested that 140 ‘rebellious Japs’ downed tools in Mossman, implying both that more labourers had arrived subsequent to those in August 1898, and that approximately half the Japanese workforce had proved ‘troublesome’ enough to be ‘sent back to their own land’.Footnote 91 Similar to the Japanese consular staff dealing with complaints from the Spreckelsville labourers in 1885 Hawai‘i, Iijima’s unsympathetic opinion of the Mossman agitators is suggested both by his report failing to discuss the strike’s origins – allegedly a labourer being struck by one of the cane-transporting rail trucks – and by his condescending descriptions of the labourers in Queensland as ‘Japanese boys’.Footnote 93

Figure 4.2 ‘Japanese and trucks loaded with cane’, Hambledon Mill, near Cairns, c. 1890.Footnote 92

The generation and preservation of reports such as Iijima’s in Tokyo was indicative of the professionalization of the Japanese overseas diplomatic service in the late nineteenth century, with the Foreign Ministry sending trained officials to Townsville in 1896 to take over consular duties which had previously been carried out from afar – and in English – by Melbourne-based Alexander Marks. Iijima’s report thus typifies the multilingual and transnational archival traces by which historians might reconstruct the complex history of the Queensland sugar industry in the late 1890s. Moreover, it hints at new ways through which to globalize that history. A few weeks before he embarked on his tour, for example, Iijima had contacted one of the most senior officials in the new colonial government of Taiwan, Gotō Shinpei (1857–1929), to suggest that the experience Japanese sugar labourers had acquired in Queensland might be of use to the recently established Taiwan Sugar Company. Perhaps one motivation for Iijima’s subsequent tour of northern Queensland was therefore the labour-relations and land-ownership lessons to be learnt for the future development of colonial Taiwan. If so, his report speaks to the more general history of transplanted sugar knowledge, personnel and capital which was occurring across and between Japanese diasporic communities in the Pacific Ocean at the turn of the twentieth century.Footnote 94

Yet for all the ways in which the Tokyo archives complexify the history of Queensland’s sugar-producing areas, the paperwork therein shared in two important ways a basic worldview with that of the Queensland politicians and newspapermen I have cited to this point. For a start, the Aboriginal peoples of northern Queensland were as absent in Iijima’s report as they were in colonial imaginations of an ‘unoccupied territory’. Of Chinese, ‘Kanakas’, ‘Malays’ and Europeans, and of their relations to Japanese labourers, Iijima had plenty of observations; of, say, the Kuku Yalanji people of Mossman, he wrote not a word. (And even if he had discussed them, he would certainly have used the generic word dojin 土人 in the Japanese parlance of the time, literally meaning ‘earth people’, rather than naming individual Aboriginal countries.)Footnote 95 Second, like the politicians with whom he was in regular contact (including Robert Philp, since December 1899 the premier of Queensland), Iijima interpreted the undeniable tensions in the north in terms of ‘the mutual relations of both countries’. In other words, in the nation-state imagination of the world for which he had been trained, northern Queensland constituted a borderland between the expansive interests of Japan and the exclusionary anxieties of Australia.Footnote 96

This co-production of northern Queensland as a remote border region was, like the NYK map, a beguilingly simplistic way of seeing the world – and one which I myself bought into during my archival research in Australia. For, after a few days in the Burns Philp Collection and also at Canberra’s National Library of Australia, I returned to Sydney by bus and flew north to Iijima’s old stomping ground of Townsville. Of a mild Saturday evening, I strolled around the historical downtown, whose colonial-era buildings have themselves been colonized by nightclubs and cocktail bars. (The historical plaque on the former Burns, Philp & Co Building, erected in 1895, noted that in the late nineteenth century the company ‘was the largest exporter of Queensland cedar – “red gold”’. A sign hanging near the building’s main entrance, displaying the graphic of a white pole dancer against a black background, promised a different currency: ‘Gold Santa Fe: Showgirls of Style, Dancers of Pleasure’.) The following morning, I hired a car and began the drive some 420 kilometres up to Mossman. Although I had not read Iijima’s report at that point, I was inadvertently tracing his route north: within an hour or two I was passing through the cane country of Ingham (site of the Macknade, Ripple Creek and Victoria mills); then Mourilyan, home of the Australian Sugar Heritage Centre museum; Innisfail (Goondi) and Edmonton (Hambledon) before, after an overnight stay in Cairns, I took the Captain Cook Highway first to Port Douglas and then on to Mossman.Footnote 97

There, at the small town library on Mill Street, a stone’s throw from the working mill, I asked about any possible Japanese graves in the area. Staff showed me a book of oral histories which included the testimony of the late Walter Mullavey, born in 1914 and interviewed in 2006. His stories meandered through the byways of his memory: they featured Jack, his gold-prospector-turned-cattle-farmer grandfather from Ireland; another Jack – ‘Jack the Kanaka’ – who’d come from the Solomon Islands and had flog marks like ‘grooves in his back’; the Chinese prostitutes who’d come up from Sydney during harvest season; and, out of the blue:

When the Japanese died up at the mill, they were the workers and the whites told them what to do, I forget what year it was, my father took them all out with a dray. You couldn’t get to Port or anywhere in the wet and he said you only dug a grave that deep and it was full of water. They were buried opposite the Rex’s cemetery, towards the mountain. They died of Mossman Fever. Dad said four or five every night. Where Rupert Howe lived, there was the Jap hospital in the mill yards. But I’ve an idea it’s gone. It was a good old building too.Footnote 98

On the basis of this lead, one of the librarians, Judy Coulthard, generously drove me a short way north to Rex’s cemetery – in reality the extended family plot of Richard Owen Jones (1852–1914), a Welsh immigrant and one of the area’s first settlers (his home was called The Cedars). From there we headed west through verdant cane fields to a site where, as the result of some phone calls, Judy had a hunch the Japanese graves might have been moved.

In the end we found nothing. And in any case, the idea of four or five Japanese successively dying each night of Mossman Fever – the local name for typhus – seemed unlikely, at least without corresponding records in Tokyo.Footnote 99 As did the story of Chinese sex labourers making a trek more than 2,500 kilometres north for work. (Did they come from Cairns instead?) As did a boast that Mullavey made about avenging ‘the blacks’, who allegedly murdered a Mossman River selector in March 1885. In the wake of the murder, he recalled, the settlers and the police, aided by ‘a lot of black trackers’, chased the Aboriginal people ‘right up onto Rifle Creek. And they said they shot 112, the whole tribe.’ There was undoubtedly some basis for Mullavey’s claims, but unlike the widespread newspaper coverage concerning the white victim, there was very little public information on the massacre – which would have counted as one of the biggest in Queensland’s blood-soaked history.Footnote 100 As I headed down south, to spend several days in the more familiar territory of Brisbane’s Queensland State Archives, I was left with the impression that empirical truths might be unknowable in the borderlands: that here even more than elsewhere, historical facts must compete with boasts and blindspots, hunch and hearsay.

Which, I would later realize, was an entirely unoriginal observation and one reinforced by what we might call the archives’ directionality – that is, their position in the south, looking towards the north. In his magnum opus on the Mediterranean, Fernand Braudel described a similar directionality in terms of the upland mountains and the lowland plains:

The history of the mountains is chequered and difficult to trace. Not because of lack of documents; if anything there are too many. Coming down from the mountain regions, where history is lost in the mist, man enters in the plains and towns the domain of classified archives. Whether a new arrival or a seasoned visitor, the mountain dweller inevitably meets someone down below who will leave a description of him, a more or less mocking sketch.Footnote 101

In other words, the archival descriptions of mountain dwellers were generated by those ‘down below’. In late nineteenth-century Queensland, too, descriptions of the north were plentiful – exacerbated, if anything, by the alleged absence of inhabitants. But such sketches were imbued with the physical and imaginative distance that separated the speaker’s (or writer’s) audience from the realities on the ground. In the resultant empirical mist, authority had to be claimed on the basis of experience. ‘Any man who travels about the colony – and especially in the North – must see the large numbers of Japanese who are now engaged in every line of business,’ argued W. H. ‘Billy’ Browne (1846–1904), in opening the Legislative Assembly’s 1895 debate on ‘Asiatic and African Aliens’. Browne himself had worked extensively in the north, and he represented the northern constituency of Croydon; and thus his long speech was peppered with claims – I have seen, I have worked, I have been, and therefore I know – which implied his colleagues had not seen, worked or been in the north, and therefore did not know about ‘the large numbers of Japanese’. If only Browne’s colleagues would travel north from the urban settlements of the south, they would know.Footnote 102

Time and again, Queensland’s politicians used a language which spoke to a popular imagination of the distant north – even if they themselves represented northern areas. Mr Hamilton, member for the vast northern constituency of Cook, asked Mr Browne if ‘the hon. Member require[d] to go as far as Thursday Island’ to find evidence of Japanese ‘Yokohama’ red-light districts (see Chapter 5). Mr Ogden, representing Townsville, reminded the assembly ‘that this matter affects North Queensland more than the South, and that the North is practically made an experimenting ground for these cheap classes of labour, and in the North we have to suffer the whole of this’. Browne talked of ‘a lot of communications [which] came down from the north-west about the Chinese coming across from the northern territory’, while Mr Archer (Rockhampton) simply spoke of the ‘danger of an influx of Japanese […] up North’.Footnote 103 This rhetorical distance of the North from the seat of government served also to reinforce claims about northern Queensland’s proximity – ‘within a few days’ sail’ – to Asia, and its concomitant ‘position of danger’.Footnote 104

Thus, the distant North was foundational to the claim of the empty North. Distance pervaded the archival reports coming from the far northern offices of Burns, Philp & Co to its Sydney headquarters; it was there in every bulletin transmitted ‘by telegraph’ to Townsville-, Rockhampton- or Brisbane-based newspapers; it was present in Iijima’s preface, noting that one of the three weeks he had been away from Townsville was simply for travel; and it remains in the title of the company-sponsored history of Mossman, Northern Outpost. In a similar way to Iijima, my memories of driving all the way up to this outpost formed a lens through which I approached the Queensland State Archives upon arrival in Brisbane. The action was up there; I was reading it from down here.

This was history from the south writ large: an Anglo-Celtic imagination of Australia, according to Regina Ganter, in which the national narrative started in 1788 with the arrival of the First Fleet in Sydney Cove and worked its way upwards.Footnote 105 And without realizing it, mine was also an imagination which took for granted the finished map of post-1901 Australia as the natural territorial conclusion of that settler history. My archival research had started in Canberra, a capital city which would not have existed other than for the fact of federation. Like the NYK map I found there, I imagined a country with its land borders at the northern Queensland coast – thereby overlooking the fact that the Australia of the 1920s was not the inevitable outcome of historical contingencies in the 1890s. Moreover, as if following the Yamashiro-maru’s route down from those distant borderlands to the civilized urban centres of the south, my return archival itinerary took me from Port Douglas to Brisbane and finally to Sydney – the ‘London of the southern seas’. There, in the Darling Harbour constituency once represented by Billy Hughes, I visited the National Maritime Museum of Australia. Like other tourists on the day and no doubt over the years, I stooped my way through the unfathomably cramped quarters of the replica Endeavour. The ship in many ways frames the museum, as if the national maritime story can only begin with Captain Cook and sail its way north.

But what, Ganter asks, ‘if we start to write Australian history from north to south, instead of the other way round, and chronologically forward instead of teleologically backward’? Straightaway, she argues, historians must ‘give up the idea of Anglo-Celts at the centre of the Australian universe’. This is a suggestion whose archival implications are left unmentioned.Footnote 106 But to the question of where, archivally, we might begin such a reverse-directional history, one credible answer was hanging in the museum’s Tasman Light Gallery. It challenged the notion of a maritime narrative which must by default be national. It also drew attention to two common critiques of the ‘borderlands’ framework which in my mind I had posited to this point: namely, that ‘a nation-state focus in borderlands history risks obscuring the histories of Indigenous peoples whose lands had been colonized or were at risk of colonization’; and that it focuses too much on land.Footnote 107

My archival departure point was a bark painting by Djambawa Marawili (born 1953), entitled ‘Baraltja’.

Delineating

‘Baraltja’ demonstrates that the most fundamental claim of the ‘N. Y. K. Line’ map concerned neither the shipping routes nor the land colours, but rather the idea that the land and the sea are separate entities which can be representationally divided by a line. In arguing against such an apparently ‘natural’ boundary, Djambawa Marawili’s work, and that of his fellow Yolŋu artists, makes an important contribution to the historian’s conception of the archive. I’ll return to this shortly – but first it’s worth reflecting on the epistemological roots of the linear division of land from sea.

Some scholars have argued that such lines are based on a ‘European cultural disposition to draw boundaries where land meets sea’.Footnote 108 Whether it is in fact appropriate to apply a single cultural explanation to a spatial entity as historically and linguistically diverse as ‘Europe’, even as scholars call for greater sensitivity to the historically and linguistically diverse histories of ‘Australia’, is a separate debate.Footnote 109 But it is true that from the seventeenth century onwards, a body of theory was produced in Europe concerning the alleged distinction between the land and the sea, which in turn offered the justification for a set of legal frameworks defining the ‘ownership’ of the former and the fundamental ‘freedom’ of the latter (themselves both terms loaded with European theory).Footnote 110 In their representations of these frameworks through devices such as lines, European imperial maps appeared to offer non-indexical interpretations of the world: that is, they claimed a set of truths which were allegedly independent of local context and were thus universal. But despite presenting the ‘truth’ of such boundaries as transcending indexicality and being globally applicable, European imperial maps were not in fact autonomous of the local theoretical context in which they were produced. They instead reflected and ‘can only be read through the myths that Europeans tell about their relationship to the land’.Footnote 111 Thus, in drawing on this imperial European cartographic tradition, the ‘N. Y. K. Line’ map must be read as advancing both a set of specific claims about Japan and Australia in the late nineteenth century and a more fundamental imperial ontology – namely, the boundary between land and sea.

Djambawa Marawili’s ‘Baraltja’ exposes this myth as indexical and therefore inapplicable to the saltwater country in which he grew up. A brief historical overview of that country helps contextualize how he does so – and underlines Ganter’s call to turn the Australian map upside down. Marawili is a senior leader of the Maḏarrpa clan in the Yirritja moiety, which, along with the Dhuwa moiety, constitutes half the world of the Yolŋu people, in what settler maps call north-eastern Arnhem Land (Northern Territory). Taking its name from a Dutch city via a Dutch East India Company ship which navigated the so-called Gulf of Carpentaria in 1623, ‘Arnhem Land’ nods to a history of European maritime contact with northern Australia that predates the British by more than 150 years. Indeed, the word for ‘White person’ or ‘European’ in many Yolŋu languages is balanda – a clear reference to Hollanders.Footnote 112

But linguists have actually shown that balanda derives from the Makassarese and Buginese word Balanda (Holland). Along with Yolŋu verbs such as djäma (to work, make, do; Makassarese/Buginese, jaäma, to build, do, work; touch, handle) or djäka (to care for, look after; jaäga, to watch, look out), or indeed the noun lipalipa (canoe-dugout; lepa), these words point to a long history of interactions between Yolŋu people and trepang (bêche-de-mer) fishers from Makassar and its South Sulawesi environs – people who themselves called the northern coast of Australia Marege’.Footnote 113 Analysis of trepang exports from Makassar to the Dutch administrative centre of Batavia and then on to the Chinese market suggests there was a sudden increase in exports in the late eighteenth century. Read against a famous encounter in 1803 between the British navigator Matthew Flinders (1774–1814), on his circumnavigation of Australia, and Pobassoo, a Bugis ‘old Commander’ of the trepanging fleet, some scholars have dated the first sustained engagements between Makassarese fishermen and Yolŋu peoples to around 1780.Footnote 114 Until trepanging from Makassar to the Northern Territory was effectively prohibited in 1906, thereby ‘islanding’ northern Australia from Southeast Asia, the impact of these engagements was profound: it can be traced not only linguistically but also archaeologically, and in Yolŋu ritual practices and rock art.Footnote 115

This Yolŋu–Makassar history is important because it refutes the stereotype of an isolated, static, ‘traditional’ Aboriginal past set against the dynamism of the post-European encounter – as if Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal history only began with Captain Cook. Yolŋu peoples were actively engaged with the world of today’s Southeast Asia from before the arrival of the First Fleet, and probably from before the arrival of the Dutch in the early seventeenth century, in a historical relationship which also changed across time. The line which divides the nation-state of ‘Australia’ from Southeast Asia is thus a historical anachronism – even if it continues to determine the infrastructures of travel in the region. Moreover, as the anthropologist Ian McIntosh argued with reference to the early 2000s, contemporary memories of Yolŋu encounters with Makassar across this anachronistic border affirmed the identity and authority of Yolŋu people as landowners and as claimants in a battle for sea rights.Footnote 116