Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Music Examples

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- List of Music Manuscript Sigla

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- SONGSTERS AND THEIR REPERTORIES

- CLOSE READINGS

- CREATING POLYPHONY

- MUSIC AS CULTURAL PRACTICE

- Works Cited

- Works by Christopher Page

- Index

- Tabula Gratulatoria

- Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Music

6 - Forgotten Levers of Harmony: Where Are the Grammarians’ Claviculi?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Music Examples

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- List of Music Manuscript Sigla

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- SONGSTERS AND THEIR REPERTORIES

- CLOSE READINGS

- CREATING POLYPHONY

- MUSIC AS CULTURAL PRACTICE

- Works Cited

- Works by Christopher Page

- Index

- Tabula Gratulatoria

- Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Music

Summary

Late in September 1979 I stood in the Bodleian Library, waiting for the precious illuminated manuscripts that I had ordered to be brought to the reading room. The purpose of my visit was to study miniatures found in medieval English manuscripts containing images of stringed instruments in general, but especially those featuring a citole. Gaining some understanding of this instrument had by then become a professional responsibility, for a year earlier I had joined Ensemble Sequentia in Cologne, specialising in early lute and other necked chordophones of the Middle Ages. Finding one's way through the forest of medieval strings was no easy task; I had learnt wonderful things about conceptualising and interpreting medieval music from classes with Thomas Binkley, but at that time this highly specialist subject had been very little studied. Clearly, by the late 1970s there was urgent work to be done towards achieving a better grasp of the form, sound, historical context, identity and usage of medieval instruments.

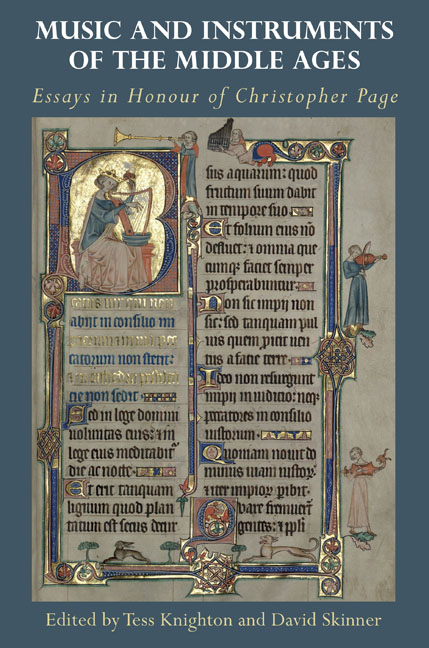

At length my manuscripts arrived. The library assistant who handed them to me asked what I was researching, and we soon discovered that we shared a common interest in an uncommon subject: medieval stringed instruments. A pleasant and animated conversation followed, at the end of which the assistant introduced himself as Chris Page. One of the manuscripts he delivered to me contained the image shown in Illus. 6.1.

While this so-called ‘holly-leaf ‘ form of the citole will always remain a personal favourite, there were other elusive instrument types from the same general period to be explored. One of the most puzzling was the subject of a letter I received some months after the Oxford visit:

Dear Mr. Young,

In reply to your interesting letter, I am sorry to say that it has been so many years since I collected pictures of intarsias for the article you know and for others which I never had time to complete, that the whole material was packed up and stored away, and it would take a disproportionate amount of time to unearth it. The most promising way for you would seem to be, since you plan anyway to go to Italy, to look up systematically choir stalls in Tuscan and Lombard churches, where most important intarsias occur.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Music and Instruments of the Middle AgesEssays in Honour of Christopher Page, pp. 173 - 192Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2020