Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

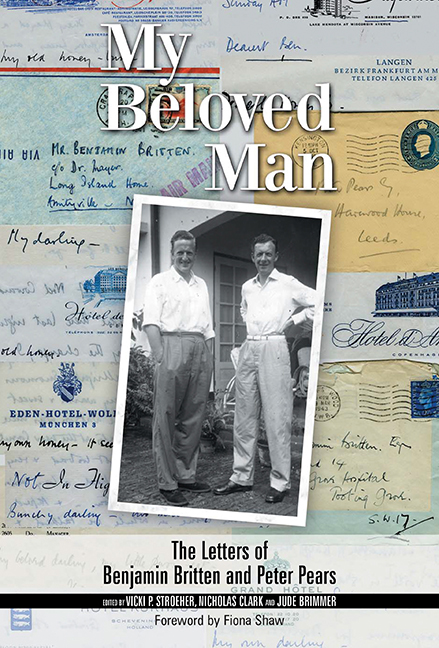

- Frontispiece

- Contents

- List of Plates

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword by Fiona Shaw

- Acknowledgements

- Editorial Note

- Introduction: Britten and Pears's ‘personal and consistent’ Correspondence

- THE LETTERS

- I ‘When I am not with you’: August 1937 to January 1941: Letters 1–12

- II ‘My life is inextricably bound up in yours’: May 1942 to November 1944: Letters 13–70

- III ‘I don't know why we should be so lucky, in all this misery’: July 1945 to April 1949: Letters 71–125

- IV ‘You are potentially the greatest singer alive’: Late 1949 to January 1954: Letters 126–88

- V ‘Why shouldn't I recognise that you are such a large part of my life’: May 1954 to December 1959: Letters 189–246

- VI ‘Far away as you are, at least I feel there is contact!’: January 1960 to March 1968: Letters 247–313

- VII ‘It is you who have given me everything’: January 1970 to June 1975: Letters 314–53

- VIII ‘My days are not empty’: January to November 1976: Letters 354–65

- Personalia

- List of Works

- Select Bibliography

- General Index

- Plate section

VI - ‘Far away as you are, at least I feel there is contact!’: January 1960 to March 1968: Letters 247–313

from THE LETTERS

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 July 2016

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Frontispiece

- Contents

- List of Plates

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword by Fiona Shaw

- Acknowledgements

- Editorial Note

- Introduction: Britten and Pears's ‘personal and consistent’ Correspondence

- THE LETTERS

- I ‘When I am not with you’: August 1937 to January 1941: Letters 1–12

- II ‘My life is inextricably bound up in yours’: May 1942 to November 1944: Letters 13–70

- III ‘I don't know why we should be so lucky, in all this misery’: July 1945 to April 1949: Letters 71–125

- IV ‘You are potentially the greatest singer alive’: Late 1949 to January 1954: Letters 126–88

- V ‘Why shouldn't I recognise that you are such a large part of my life’: May 1954 to December 1959: Letters 189–246

- VI ‘Far away as you are, at least I feel there is contact!’: January 1960 to March 1968: Letters 247–313

- VII ‘It is you who have given me everything’: January 1970 to June 1975: Letters 314–53

- VIII ‘My days are not empty’: January to November 1976: Letters 354–65

- Personalia

- List of Works

- Select Bibliography

- General Index

- Plate section

Summary

The correspondence in this chapter continues to chart Pears's career as a recitalist on the continent and in the US, as well as his final appearance at Ansbach in 1964. But it also takes account of the personal and artistic connections Britten was forging with other musicians. On 21 September 1960, the composer attended the British premiere of Shostakovich's Cello Concerto no. 1 at the Festival Hall and established what would become a life-long friendship with the soloist, Mstislav Rostropovich. At Rostropovich's request Britten composed the Sonata in C major for cello and piano for them to perform together. It received an enthusiastic reception at its first performance in the Jubilee Hall in Aldeburgh in July 1961. The Symphony for Cello and Orchestra followed in 1963 and the three suites for solo cello in 1964, 1967 and 1971; all demonstrated Britten's complete awareness of Rostropovich's exceptional musicianship, and were gifts that functioned as ‘lifebelts’, as the cellist described them. Rostropovich and his wife, the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, were frequent guests at The Red House and they accompanied and hosted Britten and Pears's visits to Russia; their enduring relationship remaining unaffected by the surrounding tensions of the Cold War. Music drew them together, but perhaps it was because the Rostropoviches also felt themselves to be outsiders, eventually defecting from the Soviet Union in 1974, that they became so close. Britten had kept Vishnevskaya's voice in mind as he wrote the solo soprano part of his War Requiem, which he began composing in April 1961. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, for whom Britten composed the baritone part, also joined the select list of artists to whom Britten dedicated works, premiering the Songs and Proverbs of William Blake in June 1965. The composer admitted to Pears the difficulty he experienced in writing for other singers (see Letter 290), although Pears had his own connection with the piece, having made the selection of texts to be set from Blake's work. Julian Bream, by now well established as an alternative recital partner for Pears, was also the recipient of a work written for and dedicated to him. Nocturnal, after John Dowland (1964) was based on Dowland's song Come, Heavy Sleep, from the repertoire in which Bream specialised.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- My Beloved ManThe Letters of Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, pp. 265 - 328Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2016