July 1, 2009, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia

“The scar marks from the beatings, do they still remain to this day, Uncle?” Judge Non Nil, the President of the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, asked civil party Bou Meng. “Or are they healed and all gone?”Footnote 2

On July 1, 2009, Uncle Meng had taken the stand during the first case being held by the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC or “Khmer Rouge Tribunal”), an international hybrid tribunal established to try the surviving leaders of the Khmer Rouge.Footnote 3 Elevated on a raised dais in front of Uncle Meng sat the Trial Chamber, comprising two international and three Cambodian jurists, one of whom was President Nil.

To Uncle Meng’s right sat defendant Duch, the former commandant of S-21, the secret interrogation and torture center where Uncle Meng had been imprisoned and tortured during Democratic Kampuchea (DK), the period of Khmer Rouge. Over 12,000 people perished at S-21, a former high school that was at an epicenter of a campaign of mass murder, terror, and repression that resulted in the death of perhaps 1.7 million of Cambodia’s 8 million inhabitants (Chandler Reference Chandler1999; Hinton Reference Hinton2016; Kiernan Reference Kiernan2008).

Sixty-eight-year-old Uncle Meng, a short balding man with a raised chin and face marked by deep furrows cascading down from his outer eye – a sign of hours spent farming under the sun that also gave the appearance of perpetual grief – was one of a small number of S-21 survivors. Uncle Meng survived because he could paint, though not before he had been tortured, an experience he had just finished recounting to the court.

“[They’ve] healed already. But there are scars all over my back, Mr. President,” Uncle Meng replied to Judge Nil, motioning toward different parts of his shoulders and back. “You can even see them on the back of my arms.” He continued, “They lashed me with the end of a whip while I lay face down on the ground. They beat me one by one, switching when they got tired.” Bou Meng paused and then said, his voice barely audible, “Five of them were there, beating me at the same time.”

“Can we please see the scars briefly?” Non Nil asked, motioning to Bou Meng to come forward. “Yes,” Uncle Meng replied. “[You] can.”

As the court waited, Uncle Meng’s German lawyer, Silke Studzinsky rose to intervene. “Mr. President, I would like [us to take a] break now before Mr. Bou Meng shows his scars and to decide if this is appropriate.”

It was the second time Studzinsky had intervened on behalf of her client that morning. As the proceedings had commenced, Studzinsky had asked to “make some observations.” The previous day, she noted, another civil party and S-21 survivor “was overwhelmed sometimes when he [re]counted his story and he had to cry, and he could not control his emotions any more.” Glancing up at the judges as she read from her notes, she continued, “He shares his traumatization” as well with “[Uncle Meng], who is my client.”Footnote 4

Accordingly, Studzinsky requested the court assure witnesses “that if they need time to cope with their emotions … that they can be sure to have this time before they continue with their testimony,” perhaps including “a short break” in which “to recover.” In addition, the court should offer assistance from psychological support staff.

Uncle Meng felt “strong” and looked forward to testifying, Studzinsky concluded, but “at some points of his story, [might become] very weak and will be moved very much by his emotions.” At such times, it would be appropriate to give him time to “relax” before proceeding.

Studzinsky’s intervention was linked to the larger backdrop of civil party representation. She was the international lawyer for civil party Group 2, which included Cambodian local non-governmental organizations offering counseling and assistance for distressed witnesses and civil parties.Footnote 5 This larger backdrop of mental health services and concern about trauma was behind Studzinsky’s initial remarks and suggestion that Bou Meng be offered psychosocial support if distressed.

“The Judges,” Judge Nil replied to Studzinsky, were “monitoring and observing the proceedings” and had noted the survivors were “very emotional.” Mental health support staff were on hand to assist. The Trial Chamber had also observed that the witnesses were able to compose themselves and get “under control to respond to further questions.”Footnote 6 The court did not want to “incite the emotions of the witnesses until he or she cries,” but if it happened the judges would “take immediate action” to ensure the witness could “control their emotions.” Then he called Bou Meng to the stand.

“Uncle,” Non Nil instructed, “Could you please tell the court about your experience[s] during the Khmer Rouge regime from April 17, 1975 to January 7, 1979?”Footnote 7

This chapter explores Bou Meng’s reply and what his experience testifying at an international hybrid tribunal says about the ways in which justice is translated across different epistemological and cultural domains. Bou Meng’s experience, I contend, involved both desire and exile.

6.1 The Testimony of Uncle Meng: A Traumatized Survivor Who Painted Pol Pot amidst Screams for Help

In 1977, Uncle Meng and his wife were working, like many Cambodians during DK, on a rural cooperative, building dams and digging canals. The labor was difficult, pushing him to the limits of his physical abilities.

One day he was told that he was being sent to the University of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh to teach. He was pleased. When he realized that their car was not headed in the direction of the university, “I felt uneased and I felt a bit scared and I felt I was dizzy.” Uncle Meng and his wife were driven to a house by S-21 and suddenly ordered to “put our hands behind our backs and they cuffed our hands. Then my wife started crying and said, ‘What did I do wrong?’”Footnote 8 Their dehumanization was immediate. A guard replied, “You, the contemptible, you don’t have to ask. Angkar [the Organization] has many eyes, like pineapples, and Angkar only arrests those who make mistakes or offence.” Uncle Meng thought about his work at the cooperative and “could not think of any mistake that my wife and I made.”Footnote 9

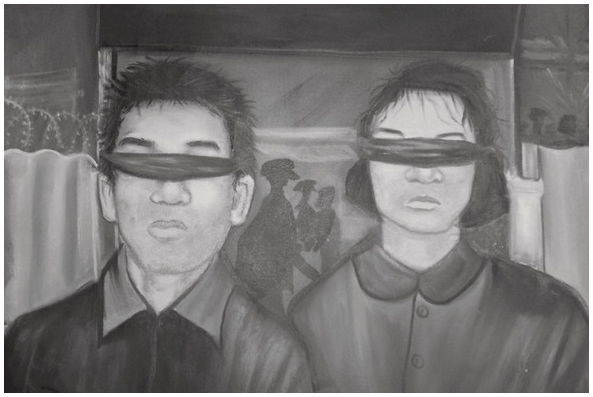

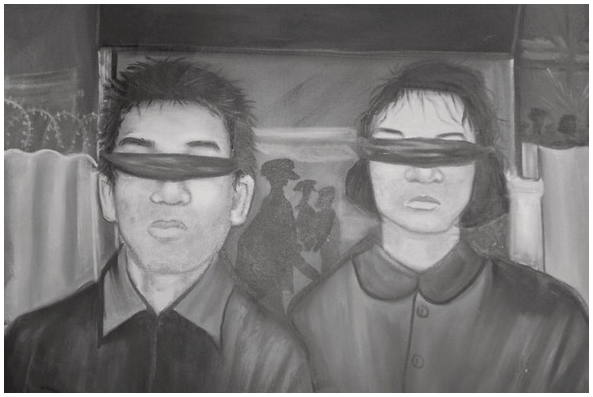

They were blindfolded and led into S-21 to be registered (as illustrated in Figure 6.1). “After they photographed my wife,” Uncle Meng told the court, “they photographed me.” He never saw her again. Today, the only photograph of his wife that he has is a copy of her S-21 mugshot. “I would like to show [it] to the judges,” he stated. “Her name was Ma Yoeun alias Thy,” Uncle Meng said as her black and white photograph was displayed on the court monitor. Her hair is cropped short, revolutionary style; a white tag with the number “331” is pinned to her black shirt. “She was about 25 years old.”Footnote 10

Uncle Meng was taken to a cell “in which about 20 to 30 detainees were placed. They all looked like hell because their hair grew long … I felt dizzy when I entered the room and I was so confused.”Footnote 11 He was stripped to his underwear and shackled by the ankle. The prisoners’ speech and movement was restricted; they had to request permission even to relieve themselves into an old ammunition can or plastic jug. Guards beat prisoners who made too much noise with a stick.Footnote 12 Uncle Meng recalled that a guard once stomped on the chest of the prisoner lying next to him. The prisoner coughed blood and died.

Food was minimal. “I was always hungry.” Uncle Meng recalled. “When I saw the lizard crawling on the ceiling I would wish that it dropped down so that I could grab it and eat.”Footnote 13 The prisoners were bathed infrequently and hosed down. “I used to raise pigs,” Uncle Meng noted. “When I washed my pigs, then I water-hosed my pigs and I used my hands to clean my pigs. But [at S-21] I was even lower than my pigs or my dog because no soap was used, no scarf was used to change or dry my body.”Footnote 14 The guards, Uncle Meng recalled, made jokes about the prisoners’ naked bodies, mocking the size of their private parts.Footnote 15 The prisoners became thin, grew weak, and got “skin rashes and a lot of skin lice. It was so itchy.”Footnote 16

Worse was to come. Prisoners disappeared. Uncle Meng had an idea of what happened since the guards threatened that they would “peel my skin.” A prisoner who slept next to Uncle Meng explained this meant “you will be beaten during the interrogation and I felt so horrified in my mind. I was so shocked. I thought, what mistake did I make.”Footnote 17

Four or five months later, Uncle Meng, in a severely weakened state, was interrogated. He was led, blindfolded and handcuffed, to a room where he was ordered to lie, face down, on the floor, his ankle shackled to a bar. His interrogators asked if he was CIA or KGB. “I told them I did not know anything,” Uncle Meng told the court.Footnote 18 “They had a bunch of sticks and they dropped [the pile] on the floor and it made noise,” Uncle Meng continued. “And I was asked to choose which stick I preferred. And I responded, ‘Whichever stick I choose, it is still a stick that you will use to beat me up so it is up to you, Brother, to decide’.”

Then Mam Nai, one of Duch’s top deputies, “stood up and grabbed a stick and started to beat me.”Footnote 19 Unclue Meng recalled “He asked me to count the number of lashes. When I counted up to 10 I told him, and he said ‘It’s not yet 10, I only hit you once’. And I can remember his word … I can always remember his face, the person who mistreated me.”Footnote 20

As many as five interrogators took turns beating Uncle Meng. “I felt so painful,” Uncle Meng went on. “There were wounds – many wounds on my back and the blood was on the floor flowing from my back. Whips were also used to torture me. I was so shocked and painful.”Footnote 21 Uncle Meng kept telling his interrogators that he didn’t know how to answer their questions: “I could not think of any mistake that I made. I did not know what the CIA or KGB network was; then how could I respond. So they just kept beating me. In my mind, I thought of my mother.”Footnote 22 His back was covered with wounds, which his captors would sometimes pour gravel into or poke.

Uncle Meng’s torture continued for weeks, during which he slept in a tiny individual cell. Uncle Meng was tortured in various ways, including being given electric shocks so severe he lost consciousness. Despite the torture, Uncle Meng claimed he never confessed. “I gave the same response every day,” he testified. “I did not know who was the leader or who introduced me into the CIA or KGB.” In the end, his interrogators wrote up “a false confession and ordered me to sign. I can not recall the content of that confession,” but “inside my heart I of course did not approve.”Footnote 23

After signing his confession, Uncle Meng was returned to a communal cell. One day, toward the end of 1977, a young cadre asked, “In this room, who can do the painting?” Uncle Meng was an artist, “So I raised my hand. I said, ‘yes, I can do the painting’.”Footnote 24 He was unshackled and tested. “They wanted to know whether I was really a painter,” Uncle Meng said, so “they gave me a paper and a pencil so that I could draw.”Footnote 25 After Uncle Meng had proved his ability, he was transferred to a small artisan workshop (illustrated in Figure 6.2). The artists were given better food and allowed to sleep without chains. And they survived. Almost every other S-21 prisoner, including Uncle Meng’s wife, was executed.

Figure 6.2 Painters and sculptors in the S-21 artisan workshop.

Uncle Meng’s first assignment was to paint a large portrait of Pol Pot based on a photograph of the Khmer Rouge leader. As Uncle Meng worked, Duch sometimes sat “nearby me, watching me, sitting on a chair with his legs crossed,” even offering suggestions.Footnote 26

If he did not personally harm Uncle Meng, Duch made threats, including a warning that, if his portrait of Pol Pot was flawed, Uncle Meng would be used as “human fertilizer.”Footnote 27 As for the abuse of other prisoners, Uncle Meng recalled an incident involving a Vietnamese man who claimed he could make wax molds. The man “was tested and Duch saw that he could not do it. Then he ordered the interrogators to kick him like kick[ing] a ball.”Footnote 28 The man disappeared. Another time, while painting, Uncle Meng witnessed an incident in which female guards kicked a pregnant woman because she was not walking quickly enough.Footnote 29 On another occasion, two guards passed his office carrying a “very thin man” whose arms and legs were tied to a pole like a pig.Footnote 30 While Uncle Meng never witnessed torture, “I heard the screams; people crying for help all around the compound.”Footnote 31

After the defense challenged him on this point, Uncle Meng swore “right before the iron genie” that if he was “exaggerating anything, then I would be run over by a bus.”Footnote 32 The defense also noted there were inconsistencies in Uncle Meng’s testimony, a point Uncle Meng acknowledged, explaining “it is because I have been severely tortured … if I made any mistake in my testimony it is result from the very poor memory of mine; resulted, of course, from such torture.”Footnote 33 As he finished, he was close to tears.

Indeed, Uncle Meng’s suffering, past and present, was a central theme during his testimony, displayed most visibly in his description of his torture, the many times he lost his composure, and his scars. Besides memory problems, Uncle Meng said that his torture and imprisonment had resulted in ailments such as hearing loss, poor eyesight, and premature aging. He had consulted with mental health professionals and was given medication “so that I would not have insomnia, and I take two types of tablets.”Footnote 34

In many ways, the emotionality of Uncle Meng’s testimony peaked when he posed a question to Duch through President Non Nil near the end of the day. “Mr. President,” Uncle Meng requested, “I would like to ask him where did he smash my wife.” Uncle Meng explained that he had searched for her after DK to no avail and assumed she had been executed. He just wanted Duch to “tell me where she was killed or smashed. Then I would go to that location and just get the soil … to pray for her soul.”Footnote 35

Duch replied that he was particularly moved by Uncle Meng’s testimony and wanted “to respond to your desire, but it was beyond my capacity because this work [was] done by my subordinate, but I would like to presume that your wife might have been killed at Boeung Choueng Ek.” Duch added, “Please accept my highest assurance of my regards and respects toward the soul of your wife. That’s all.”Footnote 36 Uncle Meng began to cry (MacDonald Reference MacDonald2009) (Figure 6.3).

If this brief synopsis provides an overview of Bou Meng’s testimony, it is a particular type of account, as the discussion that follows will demonstrate. This account is redactic (Hinton Reference Hinton2016), editing out information that is less relevant to – or even threatens the integrity of – the juridical articulation in the making. Nevertheless, traces of the editing process remain, both obvious (the juxtaposition of quotations from the trial transcript with my summary indicating the text is truncated) and more indirect (the sometimes odd court translations of Bou Meng’s quotations). These traces suggest an excess of meaning that has been elided as well as the juridical disciplines that produce legalistic narratives and subjectivities, ones foregrounded in what I have elsewhere called “the justice facade” (Hinton Reference Hinton2018; see also Hinton Reference Hinton2022). This productivity was evident at moments such as the deliberations over Bou Meng’s scars, Studzinsky’s remarks about civil party emotion, and Bou Meng’s very entrance into the court, a moment to which I now return.

6.2 Translation and the Trials of the Foreign

“Court officer, bring the survivor, Bou Meng, into the courtroom,” Non Nil had instructed at the start of the proceedings.Footnote 37 A moment later, Uncle Meng, wearing an untucked dress shirt, top buttons unfastened, entered the courtroom. Clasped in both hands, he carried an enlargement of his wife’s S-21 mugshot, which he carefully set on the desktop of the witness stand. The court official who had led Uncle Meng into the courtroom helped him put on a headset, which almost everyone in the courtroom wore.

“Uncle, What’s your name, Uncle?” Judge Non Nil began.

“[My] name,” Bou Meng said, bumping the microphone set on his desk as he rose to his feet. “Bou Meng.”

“Uncle, you can sit down, because the proceedings will be really long and we will have a full day to hear your testimony,” Non Nil instructed. “The Trial Chamber judges give you permission to sit.” As Bou Meng quickly sat down, an illuminated red band at the bottom of the head of his microphone ceased to glow.

“Second. Uncle, before you respond to my questions,” continued Non Nil with a slight smile,

Uncle, could you please wait until you see the red light on the head of microphone before Uncle begins speaking. If Uncle speaks when the red light is not on, the sound will not reach the interpreters. As a consequence, the translators won’t be able to translate and thus the international colleagues in the proceedings and public gallery would not hear what you are saying.Footnote 38

Finally, Non Nil noted that, since Bou Meng had hearing problems, “when you listen to any questions you should be quiet and wait until the red light is on. Then you can respond.”

With these words, delivered less than thirty seconds after Uncle Meng had settled into his seat, President Non Nil introduced Uncle Meng to the disciplines of the court. His remarks centered on this issue of translation and a related technology: The microphone. Like other international tribunals, translation is simultaneous at the ECCC. The primary language, projected into the public gallery by a speaker-system, is Khmer. Everything that is said in Khmer is immediately translated into English, then from English into French. All the participants must speak one of these three official languages. Bou Meng’s headset included channels for each language.

The words Bou Meng had spoken, “[My] name … [is] Bou Meng,” had taken a journey from the microphone on his desk to the headsets of those listening in other languages. Non Nil had quickly summarized this semantic flow as Bou Meng’s “message” was sent to the translators who then conveyed it to the international participants, who otherwise “wouldn’t hear or understand.” The translators sat out of sight in an enclosed second floor room at the back of the public gallery.

For translation to take place, Bou Meng had to act in specific ways. In the aforementioned sequence, Non Nil told Bou Meng that he had to wait until the red band on the head of his microphone illuminated before speaking. If he spoke out of order, his voice would not be heard. Just a few minutes later, Non Nil would repeat these instructions, adding that Bou Meng should “not answer too quickly, Uncle, watch for the light before [responding]. Uncle, speak a bit more slowly. Watch for the light until you see [the red light] on my microphone is off.”Footnote 39 As Bou Meng’s testimony proceeded, he continued to be coached on how to speak and what to say, instructions part of a larger process in which Bou Meng’s speech and behavior were regulated by juridical disciplines and technologies.

If this sort of courtroom “translation” refers to the particular “process of turning from one language into another,” the term has a more abstract meaning of “transference; removal or conveyance from one person, place, or condition to another,” an action that involves “transformation, alternation, change” (OED Online 2014b). This general sense of transportation from one state to another is captured by the etymological connection of “translation” to “transfer,” which comes from the Latin transferre, “to bear, carry, bring” (transferre) “across” (trans-). The Khmer term Non Nil used, bok brae, has a roughly similar sense, suggesting a removal (like peeling the bark off a tree) and a transformation into a different form (Headley et al., Reference Headley, Chhor, Lim, Kheang and Chun1977, 459, 600). In both cases, there is a suggestion of something “stripped away” from one context and transformed as it is introduced into another.

In non-literary contexts, such as translation at a tribunal, it is often assumed that, while everyone recognizes a “loss,” the task of translation is a more or less straightforward technical exercise. Within the field of translation studies, however, there has been much debate about what happens during the “transfer,” as “the text” is translated into another language (Venuti Reference Venuti2012, passim). Even if there are key differences in the translation of a literary text and trial testimony, the two converge in the centrality of translation in the courtroom on both linguistic (translation into a foreign language) and discursive levels (a translation into juridical form). Discussions in translation studies therefore provide a way to re-approach the disciplines that structured Bou Meng’s testimony. Accordingly, I now make another return, a re-examination of Bou Meng’s testimony as, to use translation theorist Antoine Berman’s term, a “trial of the foreign” (Berman Reference Berman and Venuti2012), involving justice as exile, desire, appropriation, and de/formation.

6.3 Justice and Trials of the Foreign

6.3.1 Justice As Exile

Justice entails exile. The departure leads to change; change means that there can be no return to the origin. A secondary sense of “exile” captures this fact: Exile as “waste” and “ruin.” What was familiar becomes strange, but uncannily so since it bears the trace of its origin, the “home” for which the translation longs. The translation is a look-a-like, a double that can never duplicate the original, a double that is itself further doubled, replicated, parsed, fragmented.

The temporality of what I have elsewhere called the “transitional justice imaginary” (Hinton Reference Hinton2018) is illustrative as a post-conflict society is imagined as one of transformation whereby, through the transitional justice mechanism, it moves along a linear trajectory from an original state of “ruin” to one of liberal democratic change and “development.” Inflecting this trajectory as one of “exile,” however, highlights the point that the process is not just one of emancipation but also loss, and perhaps even “ruin” – a lack that infuses the process, a disjuncture between what is seen, desired, and imagined. Bou Meng’s testimony also illustrates this point, beginning with the very act of translating his testimony in court.

As Bou Meng speaks into the microphone, his words are converted, first into electrical signals that travel to the translation booth, then into English, and from English into French. The glowing red band on the microphone signifies the exile-in-the-making of his testimony; then the light darkens and is gone, like his words that have been carried across to the headsets of those listening in different languages. The words cannot return. Back-translation is impossible even if the trace of the origin remains in the de/formation, awkwardness, and gaps in the translated text.

For instance, when Studzinsky spoke of the “emotional difficulties” of her client, the English term she used was translated as sâtiarama, a Khmer term linked to Buddhist mindfulness and the proper focus of consciousness versus the turbulence of a consciousness out of balance. Indeed, idioms of balance are central to understanding Khmer ethnopsychology and have humoral dynamics and somatic manifestations that are glossed over in a straightforward translation using a biomedical category like PTSD. In this sense, Bou Meng’s emotive disposition is “exiled” in translation, becoming something “other” that points “home” to his emotional disposition but is unable to return to it since it involves a complicated semantic network, the “bushy undergrowth” (Berman Reference Berman and Venuti2012, 244) of a particular context that is masked by the justice facade. Sâtiarama becomes “emotion,” stripped of its Buddhist connotations and filtered into a Global North biomedical frame suggesting PTSD.

This frame is deeply enmeshed with the transitional justice imaginary, which asserts a traumatized and wounded victim awaiting the healing provided by the transitional justice process (Hinton Reference Hinton2018). Bou Meng is portrayed in a similar manner, as illustrated by Studzinsky’s comment that Bou Meng “shares his traumatization” with other “survivors, victims, civil parties and witnesses” in need of mental health services.

To highlight Bou Meng’s traumatization, as part of a larger legalistic frame of “suffering” required for civil party participation, Cambodian civil party lawyer Kong Pisey asked Bou Meng if he had sought “psychological support.” Bou Meng replied affirmatively, explaining he previously “had consultation with psychological support” and received “two types of tablets” to help with insomnia.Footnote 40 This juridical framing of Bou Meng’s emotional states glosses over the ways he copes with his suffering, including praying for the souls of the dead.

Accordingly, this framing elides key aspects of Cambodian ethnopsychology. In Khmer, for example, Bou Meng explains that he takes three pills, including vitamins. These pills help his “nerves” (brâsae brâsat), a term that is difficult to translate because it refers to internal vessels that help maintain a bodily flow that, if obstructed or disrupted, may result in idioms of distress – ones that are again difficult to translate. In his testimony, Bou Meng mentions two of these somatic manifestations of psychological disruption, “thinking too much” and having difficulty sleeping, which the medicines are meant to help.Footnote 41 Of course, Cambodians have a wide variety of non-biomedical ways of treating such conditions and facilitating bodily flow, ranging from using tiger balm to pinching key parts of the body – many of which I observed Bou Meng do at the ECCC.

This “bushy undergrowth” of his understanding is “clipped away” from Bou Meng’s testimony as it is refashioned to accord with juridical order. This sort of justice as exile can be seen throughout Bou Meng’s testimony. At times, for example, Bou Meng, like other Cambodians who testified, invoked Cambodian proverbs to highlight a point. Sometimes these proverbs were translated and sometimes – as was frequently the case with trial dialogue and testimony more broadly (indeed, the English-language translations often leave out significant portions of text, especially when the translator considers it repetitious) – they were not.

Even when such idioms were noted and translated, they often didn’t make much sense. Thus, when Bou Meng tried to explain why he didn’t remember a S-21 episode another survivor had recounted (about Bou Meng having been taken away, tortured, and then forced to apologize to the other prisoner-artisans), Bou Meng replied, “I cannot recall or maybe I forgot, because I never offered my apologies to anyone … As the Khmer proverb says, ‘The elephants with four legs would have collapsed sometime and the wise person would forget anyway’.”Footnote 42

Bou Meng’s invocation of this “old Cambodian proverb” also suggests how he, like many Cambodians from rural backgrounds, often invoke agrarian metaphors, idioms, and experiences that are difficult to translate and considered irrelevant in the context of the court, particularly for foreigners unfamiliar with rural life. Bou Meng’s testimony was sprinkled with such references, such as his likening of how the prisoners were treated worse than the pigs he took care of at home.

When describing how the Khmer Rouge treated his wounds after he was whipped, Bou Meng explained that there was “no medicine, just a bowl of salt water that they poured on my back. I jerked violently. Oh, it was beyond pain, hurting more than even the beating.”Footnote 43 As an example of the enormity of his pain, Bou Meng referred to what happened when salt was poured on a frog, an analogy difficult to translate into English and for speakers less familiar with rural life. He added that he was also given “rabbit pellet tablets,” another term that doesn’t translate easily. Bou Meng explained, though it was not translated, that the tablets were called this because they looked like “rabbit feces.” Taking them gave Bou Meng a headache and made him feel dizzy, symptoms that again suggest a disruption in proper bodily flow according to Cambodian ethnopsychology. While this “treatment” healed his open wounds, Bou Meng said, invoking a Buddhist idiom, he experienced “enormous suffering” (vetonea nas).

6.3.2 Justice As Desire

Bou Meng’s invocation of “suffering” returns us to that glowing light, a reconsideration of it as the flame of desire. Desire involves a longing as well as unconscious process, something tucked out of sight – like the cord of Bou Meng’s microphone that trails away into an underground circuitry carrying the current of his speech to the overhead translation booth that remains largely unseen, where it is transformed again, and transmitted once more, this time via radio waves, into the headsets of those listening to the translation.

If justice as exile focuses on banishment, justice as desire directs us toward the vehicle of that banishment, the circuitry that is glimpsed but then passes out of sight as the translation takes place. On one level, desire is on display, foregrounded like the illumination of the microphone’s red light. But it is also “unconscious,” largely out of sight like the translation booth and the electrical currents that transmit sound underground.

There are many ways to approach this “unconscious” process, including as a psychoanalytic current. Along these lines, one might examine the psychodynamics of testimony in terms of what is said, heard, and repressed. Here I focus on a different and largely unconscious current of justice as desire, translation in terms of juridical order, translation as a disciplinary ordering and classificatory process producing subjectivities.

Bou Meng may recount his experiences in a variety of forums: At home, to his children, through his art, to the media, by memoir, during lectures, and so forth. His speech act may vary across these contexts as through time. The court is a particular field in which speech and action are constituted within a terrain of affordances and constraints that canalize what is said and done (Hinton Reference Hinton2022).

While this process began with legal consultation and socialization long before Bou Meng arrived at the courtroom, the impact of juridical canalization is immediate as Bou Meng enters the court and is subjected to a legal regimen. He is shown where and how to sit and symbolically hooked up to the translation apparatus of the headset and microphone. When he stands and bumps the microphone, Non Nil instructs him on how and when to speak. In doing so, Non Nil invokes the power of the juridical regime, noting that the Trial Chamber authorizes Bou Meng to sit and expects him to watch the light on the President’s microphone – indirectly referencing the power of the Trial Chamber to regulate and even cut the sound from the participant’s microphones, one dimension of the court’s regulatory and monitoring role.

The court’s canalization of Bou Meng’s testimony further emerged in Non Nil’s initial background questioning. Soon after instructing Bou Meng on the use of his microphone, Non Nil asked Bou Meng to describe his experiences during the DK period, noting “If you can, describe all those accounts. If you cannot, then the Chamber would put some questions to you” regarding DK and S-21.Footnote 44 “My apology if I cannot recall the exact date due to the serious torture that I received,” Bou Meng replied, “My memory is not in great shape.” He went on to note his hard labor in the re-education camp, the shock of arrest, and his torture. “[T]hey just kept beating me,” he testified. “I had a lot of scars on my back as evidence from that torture.”Footnote 45 Then he began to cry, at which point Non Nil encouraged him to fortify his consciousness (satiarama) so he could tell his story.

Soon thereafter, however, the discursive mode shifted, as the judges and then the different parties had the opportunity to question Bou Meng. If Bou Meng emphasized his suffering, the Judges asked questions directly linked to the legal facts of the case, ones defined by the criminal allegations and applicable law. In this frame, Bou Meng’s replies became much shorter and were “clipped,” as illustrated by the following exchange:

President Non Nil : “Do you think [your wife was] killed at S-21?”Footnote 46

Bou Meng : “Your question reminds me [of] the question that I would like to ask to Mr. Kaing Guek Eav. I want to know whether he asked his subordinates to smash my wife at S-21 or at Choeung Ek [killing field] so that I could collect the ashes or remains so that I can make her soul rest in peace” [45]

Judge Non Nil : “You have not answered to my question …”

Later, Non Nil would state more directly, “… A witness is not supposed to give a kind of presumption because it is not really appropriate … [I]f the question is put to you whether you say that you saw it or you didn’t see it, you should just say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and please try to avoid giving your presumption.”Footnote 47 Here we catch yet another glimpse of justice as desire, the often unconscious undercurrents that shape “the said” to fit into the juridical discursive order.

Indeed, my initial description of Bou Meng’s testimony was directly modeled after the summary of Bou Meng’s testimony done by a lawyer working as a trial monitor (MacDonald Reference MacDonald2009). I even took the first section heading from her account to structure my account according to a legal framing. The legal monitor’s remarks, like other juridical accounts including the verdict, which ultimately emerge from such testimony, focus on tropes of victimhood, inhumane treatment, and suffering, which directly tie to his status as a victim and civil party and the larger factual allegations of crimes against humanity.

As the testimony is canalized and later recategorized (as it is summarized and added to the legal databases of the parties), it is pruned and clipped in accordance with juridical “desire.” We return to the notion of “exile,” as well, as Bou Meng’s testimony is “borne across” to another modality of being, words that are no longer his own, but now part of the court record.

6.3.3 Justice As Appropriation

“[D]ecide if this is appropriate.”Footnote 48

Just as Bou Meng was about to remove his shirt and display his scars in the courtroom, Studzinsky intervened and requested the Trial Chamber to reconsider. Studzinsky’s actions likely had to do with her earlier remarks about the need for the court to be more attuned to the emotions and trauma of her clients as well as the fact that Bou Meng’s scarring was extensive and would require taking off his shirt and publicly revealing his torso.

After the break, President Non Nil announced that the Trial Chamber had cancelled its “request to show the scars on the survivor’s back.”Footnote 49 Non Nil said photos of the scars could be used. “Mr. President, I do not have any photos of the marks,” Bou Meng informed him. “I only have the marks on my body.” Bou Meng agreed to have photos taken after the hearing (Trial Chamber 2010, 85 [note 444]).

This exchange regarding Bou Meng’s scars revealed a moment of what might be called “justice as appropriation.” If justice as exile involves a departure from which there is no return and justice as desire an attempt to “carry across” what is being translated in a particular way (to accord with the juridical discursive order), then “justice as appropriation” points toward the culmination of the process, as the translation is relocated to “the other side” to which it has been borne.

This appropriation takes place in at least two ways. To “appropriate” something is to take possession of it, to make that thing, as the etymology of the term suggests, “one’s own” (OED Online 2014a). As an adjective, “appropriate” suggests that which is proper or suitable to a given person, place, or condition. Justice as appropriation involves both of these senses.

Through its actions related to Bou Meng’s scar – as well as its regulation of Bou Meng’s emotion and suffering – the court “takes possession” of them, the exile becoming complete. His scars are appropriated in the juridical process, which renders them as “evidence” of his trauma and suffering. This process involves a doubling, as the original “scar” is photographed and then inputted into and redisplayed in the court record. As the trial process proceeds, Bou Meng’s scars are recast to fit with juridical desire, eventually finding ultimate re-expression as a piece of evidence supporting Duch’s conviction in accordance with the court’s legal classificatory order.

Thus, in the Duch verdict, “scars” are listed as one of a number of outcomes of “beatings” that constitute “torture techniques” (each category and sub-category being given a number, in this case “2.4.4.1.1”), which is itself a sub-category of “The use of torture within the S-21 complex” (2.4.4.1) and “Torture, including rape” (2.4.4). The sub-categories are part of the broader criminal category of “Crimes against Humanity” (2.4), which also encompasses “Murder and extermination” (2.4.1), “Enslavement” (2.4.2), “Imprisonment” (2.4.3), “Other inhumane acts” (2.4.5), and “Persecution on political grounds” (2.4.6). Bou Meng’s display of scars is referenced in a footnote and includes a specific court record number for the photographs (Trial Chamber 2010, 85 [note 444]). His experience is also described in a number of paragraphs illustrating “Specific incidents of torture” (2.4.4.1.2) (Trial Chamber 2010, 88).

This appropriation is not a simple, one-sided imposition of power, since Bou Meng has chosen to participate in the trial process. But his agency and actions, as illustrated by micro-interactions such as Non Nil’s directions about the use of the microphone and what can and cannot be said (or found relevant), are constrained by the juridical process and authority (Hinton Reference Hinton2022).

More broadly, the tribunal itself might be viewed as an illustration of justice as appropriation in the sense that Cambodia’s history – and the lived and remembered experiences of Cambodians like Bou Meng – and “transition” are in a way appropriated by “the international community.” This appropriation is manifest in the aesthetics of justice and also symbolically enacted in outreach materials (Hinton Reference Hinton, Meyersen and Pohlman2013, Reference Hinton2018; Khmer Institute of Democracy 2008).

These exiles and appropriations are naturalized in the juridical process, as the court’s work is positively inflected by the Public Affairs Section and other people linked to the court to assert that the ECCC provides “justice, national reconciliation, stability, peace, and security” as the 2003 Agreement establishing the tribunal puts it. If the ECCC provides benefits for Cambodia, it is also an institution enmeshed with power, ranging from the Cambodian government’s use of it for legitimacy to the international community’s desire to integrate Cambodia into, and thus legitimate the larger project of, the “new world order” of neoliberalism and liberal democratic practices – even as it redacts the international community’s complicated role in the conflict before, during, and after DK.

This connection to neoliberalism and democracy brings us to the second sense of justice as appropriation, or what is “fitting” or “suitable.” In addition to the appropriation of his words and his scars, Bou Meng himself is appropriated as he is transformed into a particular type of subject “suitable” to the courtroom context. Studzinsky’s intervention on behalf of Bou Meng and other victims reveals a great deal about the “appropriate” subject position into which people participating in such transitional justice mechanisms are cast. Thus, Studzinsky identifies Bou Meng as a “kind” of person (victim and legal client/civil party) characterized by a disposition (emotionality and trauma) and, implicitly, invested with certain rights and status (someone entitled to sensitivity and care).

Studzinsky’s questioning of the “appropriateness” of having Bou Meng display his scars likewise involves assumptions about his subjectivity as a liberal democratic participatory being invested with given rights, including the right to privacy and not to be partially exposed in public. Bou Meng’s symbolic entry into this realm of justice as exile, desire, and appropriation is linked to his being given a set of headphones, which symbolically render possible a translation of the juridical process.

6.3.4 Justice As (De)Formation

Through such appropriations, the legal process produces a facadist articulation of reality according with a broader set of discursive forms and classificatory orders associated with the transitional justice imaginary. All such articulations involve the redactic, an editing out of that which does not accord with the larger discursive formation in-the-making.Footnote 50 Traces of what has been redacted remain, emerging in given moments of slippage, breakdowns in translation, and sudden eruptions of the uncanny. These traces, threaded throughout Bou Meng’s testimony, suggest alternative desires and classificatory orders that have been redacted. If there is justice as formation, in the sense of the creation of a juridical articulation, then there is justice as “deformation” in the way that there is a surplus of meaning in circulation that is inevitably distorted and elided by this articulation.

What, we therefore need to ask, is “clipped” away in this juridical process of (de)formation? The moments of slippage are usually quickly pushed out of sight. Thus, Bou Meng’s initial entry into the court and his unease using court technologies and procedures does not appear in the monitor’s account. Nor does it appear in documents like the verdict. Instead, the moment passes largely unnoticed, recorded in the official court transcript but otherwise assumed to be unremarkable despite, as we have seen, being imbued with a surplus of meaning that is revealing about the justice facade naturalized at the court.

If there is justice as desire in terms of the discourses and classificatory orders that structure the juridical formation, there is also Bou Meng’s desire. This desire, due to his legal socialization, may dovetail to an extent with juridical discourses. Thus, at one point during his initial description of his DK experiences, Bou Meng noted he was happy to be giving testimony at the ECCC, which he hoped “would find justice for me.”Footnote 51 While testifying, Bou Meng made a number of such statements, as he did during media interviews and meetings with me.

But these juridical framings were basic, reflecting discursive strands linked to the transitional justice imaginary, such as the importance of the tribunal for justice, prevention, reconciliation, and educating the next generation. At the start of the trial, Bou Meng told Non Nil, “I’m not really sure whether I understand your question,” and asked the judge to phrase things in more “simplified Khmer.”Footnote 52 With the exception of Bou Meng’s references to “justice,” these notions were backgrounded in his Khmer testimony and mixed with other sorts of discourses, particularly those linked to his deep Buddhist belief.

6.4 Buddhism and Desire

In Buddhism, the notion of desire is complicated, as desire is linked to the “three poisons” (attachment, ignorance, aversion) and the resulting cravings that lead to suffering. The path to Enlightenment involves recognition of the reality, origins, and path to end suffering. To diminish suffering, then, a Buddhist should let go of craving and act ethically, performing good deeds that will condition one’s future being.

From such a Buddhist perspective, justice is bound up with this karmic principle of cause and effect. The Khmer term that Bou Meng used and that was translated into English as “justice” is etymologically linked to Buddhism and religious idioms that are deemed largely irrelevant to secular law and the justice facade.

Thus, when Bou Meng told the court that, while imprisoned at S-21, he was so hungry that he wanted to eat the lizards crawling on the cell walls, he immediately shifted into a Buddhist frame to describe his plight. “I pondered what sort of bad deeds (bon) I had done in my life to end up like this,” Bou Meng told the court, speaking slowly and looking down. “I wondered what sort of karma (kamma) from my past life was impacting me and linking me to these people. But I couldn’t see my mistake, what had led to these karmic consequences (kamma phal).”Footnote 53 Then Bou Meng, consciously contrasting the Buddhist and juridical discourses on “justice,” noted, “This is if we are speaking of the consequences of karma. If we speak we are speaking of law, then I had no fault at all.” When he proclaimed his innocence to his captors, they told him “Angkar has the eyes of a pineapple” and didn’t arrest people mistakenly.

In this courtroom sequence, Bou Meng’s Buddhist understandings suddenly burst forth in a line of juridical questioning about “inhumane acts.” His comments about karmic justice are thinly translated into English, leaving a gap in meaning that is ignored. From a legalistic perspective, the primary significance of this passage is given to the fact that Bou Meng was so hungry he wanted to eat a lizard, a comment noted by the tribunal monitor and referenced indirectly in the verdict in a footnote as one of the “facts” demonstrating the “Deprivation of adequate food” (2.4.5.1) and supporting conviction for “Crimes against Humanity Committed at S-21” (2.4) (Trial Chamber 2010, 95 [note 501]).

If Bou Meng’s comments about karma are edited out of the juridical formation, they are central to his conception of justice and story about S-21. During this part of his testimony, Bou Meng interpreted his incarceration in terms of karmic justice, which holds that one’s actions in the present condition one’s situation in the future. The Khmer word that is often glossed as “justice,” yutethoa, literally means “in accordance with” (yute) dhamma (thoa). A Cambodian Buddhist monk, Venerable Sovanratana, told me that yutethoa is that which “fits into the way of nature … the consequences of [an act] rebound upon the doer … Whatever he receives is just because of the consequences of his past actions.”Footnote 54

Venerable Sovanratana went on to explain that there is not necessarily a need for an external punishment because the perpetrator’s bad deeds naturally condition the future, which is “in accordance with dhamma.” When I asked if a tribunal accorded with Buddhism, Venerable Sovanratana replied, “Well, it’s difficult to say.” If some might say that, regardless of a trial, perpetrators suffer the karmic consequences of their action, others might say that the tribunal “is part of the result and consequences of [their karma].”

Invoking Buddhist rationalism, which emphasizes the analysis of evidence (ceak sdaeng) to discern truth from falsehood (khos-treuv) and moral right from wrong (bon bap),Footnote 55 Venerable Sovanratana continued, “whatever generates knowledge and awareness about right and wrong,” including a tribunal, “is welcome in Buddhism.” For him, the trial, as long as it is “just and fair,” is in accordance with Buddhism since “it is part of the result [of karma].” Venerable Sovanratana noted that Buddha did not oppose courts during the time that he lived and that, when a monk violated monastic rules, he might be brought before a monastic court. “So Buddhism does not teach us to wait for the ripening of karma to produce a result … From that point, [a court] is not contrary to the Buddhist teaching.” Venerable Sovanratana explained that he had visited the court with some of his novice monks to learn more about “what happened during the Khmer Rouge regime” and to observe how the court was functioning.”Footnote 56

This Buddhist emphasis on correct understanding, which is central both to the Four Noble Truths and Eightfold Noble Path in the sense of understanding the reality of things, was also invoked by Bou Meng during his testimony as he noted the importance of understanding right and wrong and telling the truth. In an interview, he told me “I always tell the truth,” explaining “I’m really scared of sinning.”Footnote 57

During an interview, Bou Meng also noted the importance of perpetrators learning to distinguish “right from wrong,” since, he told me, their actions were the result of “wrong thinking.”Footnote 58 The court, he said, could help them in this regard. Nevertheless, as Venerable Sovanratana suggested, from a Buddhist perspective there is no absolute need to try perpetrators since they will inevitably suffer the consequences of their actions. To hold perpetrators accountable in a court of law, Venerable Sovanratana pointed out, also runs the risk of promoting vindictiveness: “it must not be done for retribution” but instead to determine what “happened in reality.”

Bou Meng sometimes struggled with conflicting emotions about perpetrators. When asked about his feelings toward senior Khmer Rouge leaders, he stated that, according to Buddhism, it was necessary to pity them in their old age. He also sometimes noted the importance of ending the cycle of vindictiveness, telling me, “Buddhists can’t hold grudges. If a person sins, they will always receive sin” as a karmic consequence.Footnote 59 At the same time, Bou Meng acknowledged that he sometimes “overwhelmingly” desired revenge, a feeling amplified by his scars, which reminded him of the abuses (Huy Reference Huy2008, 9 [119f]).

Thus, Bou Meng’s scars had a range of associations, including ones that strongly diverged from the juridical appropriation that occurred at the court. His scar signified social suffering, memory, somatic distress, anger, and a personal struggle between a desire for revenge and a Buddhist sanction on vindictiveness and emphasis on detachment as a means of ending suffering and cycles of revenge. Such conflicting emotions are edited out of the juridical process, with the Trial Chamber strongly warning parties against expressing hostility, anger, and malice toward defendants, emotions that are nowhere mentioned in the judgment that the court renders except to note that its goal “is not revenge” (Trial Chamber 2010, 201).

These Buddhist principles were visually depicted on the walls of Venerable Sovanratana’s pagoda, Wat Mongkulvan. Throughout Cambodia, one finds murals that depict the story of Buddha’s life and related legends. In fact, Bou Meng, whose parents sent him to be educated at a pagoda when he was five, developed his love of painting at the pagoda, where he would try to draw pictures depicting such Buddhist tales.Footnote 60 Bou Meng’s education at the pagoda – barely mentioned in his trial testimony – revolved around Buddhist teachings, including learning about the ten lives of the Buddha and about doctrine related to dhamma, merit, and sin.

Bou Meng later learned to paint murals of the Buddha’s life that included scenes similar to those on the walls of Mongkulvan pagoda. This Buddhist aesthetic included depictions of the Buddhist hells that depict future torments that parallel past sins, such as drunks having their mouths stuffed with flaming torches, gossiping women having their tongues pulled out with tongs, and a perpetrator who used a blade to kill a man being sawed in half.

Venerable Sovanratana explained that the murals symbolized “the concept of rebirth or rebecoming in Buddhism,” since what happens in the “next life depends on what men are doing in this life.” The paintings suggest what happens when people perform “unwholesome acts, like adultery, drinking alcohol, and telling lies, especially as Buddhism prescribes in the five moral principles.”Footnote 61

This Buddhist aesthetic put into relief the key Buddhist notion that one is bound by one’s im/moral acts. This sense of ethical connection also informs one’s relationship to the dead to whom, at least in lay conceptions, merit may be transmitted through prayers and offerings to monks, who act as conduits between the living and the dead. The dead, particularly those who have died violently and are not yet reborn, are thought to circulate amongst the living, sometimes appearing as apparitions or in dreams. This was especially true of DK victims, including those tortured and killed at S-21.

This belief was also critical to Bou Meng. He had nightmares and dreams about his wife. In one, “my wife appeared leading a large group of prisoners who had been executed [at S-21]. They were dressed in black and she led them in front of my house … She said, ‘Only Bou Meng can help us find justice’.”Footnote 62 Another time, when visiting Tuol Sleng, his new wife had seen a door suddenly open and shut. Bou Meng interpreted such visions as evidence that “the spirit of my wife is not calm (sngop). Therefore I want reparations to hold a big ceremony and send merit to [the spirit of] my wife.”Footnote 63

One of the early tensions between the civil parties and the court concerned the desire of some, like Bou Meng, to have individual reparations. The court was only mandated to provide “collective and moral reparations,” however, which meant that they would not receive funds to support such commemorations for the souls of the dead.

From the start of Bou Meng’s testimony, it was clear that the meaning of his participation was more deeply linked to his Buddhist beliefs and his relationship to his wife’s spirit than to any of the ostensible goals naturalized in the ECCC’s justice facade. Given this excess of meaning, a number of slippages and translation problems ensued. He entered the courtroom carrying an enlargement of his wife’s S-21 mugshot, face-forward so everyone would see her. He began mentioning her as soon as Non Nil started his questioning, a pattern that persisted throughout the day, regardless of whether Bou Meng was being asked about her. Bou Meng often stated his desire to ask Duch where his wife had been killed.

At one point, a civil party lawyer asked Bou Meng, “Today how do you feel about the fact that you are a survivor?”Footnote 64 Bou Meng’s replied that he was “so happy” and that by telling his story to the court his body and chest “felt lighter,” another ethnopsychological idiom linked to well-being that didn’t translate smoothly into English. He then shifted and began to talk about the almost incalculable suffering he had endured. “But it wasn’t just that I wasn’t able to help save my wife,” he continued. “Why did my wife have to die?”

It was because of his wife that Bou Meng became a civil party. He explained that he wanted to ask the Accused where his wife died so he could “take earth from that place as a commemorative symbol to be used to hold a ceremony to light incense and send merit to her spirit so that her heart can be calmed.” Again, invoking an idiom that did not translate easily, Bou Meng noted that, ultimately, only the Spirits of the Earth, Wind, and Water knew where the victims were killed and buried.

When Bou Meng was finally given the chance to ask Duch where he had “smashed and discarded” Bou Meng’s wife, Duch replied that he didn’t know for certain since his subordinates executed her. But given the date of her arrest, Duch continued, he presumed she had been killed at Choeung Ek.

This question and Duch’s reply ultimately had little relevance to the court’s desire for evidentiary fact and the juridical formation in the making. Such “justice as desire” diverged from Bou Meng’s desire to gather soil from the site of his wife’s execution so he could transfer merit to help her spirit be calmed and have a better rebirth. These sets of understandings are “clipped” by the court’s desire for a particular type of legal formation that accords with the transitional justice imaginary.

6.5 The Lord of the Iron Staff

Yet another rupture occurred near the end of the day when Bou Meng was being questioned by Kar Savuth, Duch’s Cambodian defense lawyer. Kar Savuth suggested that Bou Meng had contradicted himself by saying that the detainees couldn’t speak while also stating that he heard their screams. Part of Bou Meng’s reply was translated in English as “I’m not here to talk or to implicate anyone. I’m talking here, right before the iron genie, and if I talked something exaggerating anything, then I would be run over by a bus.”Footnote 65

In Khmer, Bou Meng had referred to the local court guardian spirit, or neak ta, known as the “Lord of the Iron Staff.” While dropped from the translation, Bou Meng had said, “I am speaking according to justice (yutethoa). The spirit (neak ta), the Lord of the Iron Staff, if I’m not telling the truth, may he let a car strike and kill me.”Footnote 66 As he spoke, Bou Meng raised his voice while pointing toward where the shrine of the Lord of the Iron Staff is located on the ECCC compound.

If the “iron genie” translation made little sense in English, some foreigners familiar with the court likely understood the reference to the neak ta. For some who did, a reference to such spirit beliefs may have been noticed momentarily but viewed as irrelevant, a local superstition ultimately is at odds with the (hyper-rational) juridical enterprise. Thus, while there were exceptions, when I mentioned the neak ta to international court personnel, they suggested it was quaint or expressed little interest. Some may have even considered having a neak ta in a court complex inappropriate but to be tolerated, since all Cambodian’s courts have neak ta before which oaths are sworn.

Most Cambodian observers would have immediately understood the reference to a neak ta in Khmer and that Bou Meng was swearing an oath as proof of the truth of his testimony. Neak ta are part of a folk cosmology of animistic beings circulating among the living in Cambodia (Ang Reference Ang1987; Ebihara Reference Ebihara1968; Guillou Reference Guillou2012). Almost every village has neak ta, local guardian spirits sometimes said to be the spirit of the founding ancestors of the village, who are nevertheless feared and to whom offerings are made. When offended or disrespected, neak ta, including the neak ta found in Cambodian court complexes, may inflict sickness or hardship. While the depth of belief and knowledge about neak ta varies, for many Cambodians neak ta are highly significant. This was true for Bou Meng as well as the ECCC Public Affairs Section head, Sambath Reach.

Sambath’s strong belief may be why senior ECCC administrators asked him to establish the court’s neak ta. They told Sambath, “We have to build a spirit house because every court in Cambodia has one.” Sambath began by inviting a renowned holy man from Takeo province to the court. “It was a sunny day and very hot. He poured water on every part of the compound,” asking how the different buildings would be used. “He asked where the trial would take place,” Sambath recalled. “I told him ‘over there’,” indicating the courtroom building. When the holy man poured water in an area by the court, smoke began “coming out, powerful, very strong. Then he said ‘this is the best place to build’.”

Sambath asked what sort of spirit house they should construct. The holy man closed his eyes and invited the spirits to come. “Because this is a big job he invited many spirits,” before informing Sambath that the court’s neak ta was the Lord of the Iron Staff. “The job is too big,” Sambath recalled the holy man saying to him, so they had to have “the strongest one.” Having found the court’s neak ta, Sambath enlisted the services of a well-known professor at the School of Fine Arts to construct the sculpture of the Lord of the Iron Staff. The process began on March 31, 2006 on a day when the moon was full. Sambath organized a large religious ceremony in honor of the Lord of the Iron Staff, including food, prayers, and offerings.

Every witness, Sambath noted, had to swear an oath before the neak ta. Sambath had done this. If someone did so and failed to tell the truth, then the neak ta might afflict them in some manner, as illustrated by Bou Meng’s remark.

Given the resonance of neak ta for many Cambodians, especially villagers, it is not surprising that there have been attempts to use the neak ta as a communicative bridge between local and legal vernaculars. The official ECCC booklet includes a photograph of the neak ta, and it is featured in other outreach material. The neak ta was clearly of importance to Bou Meng. During an interview shortly after he testified, I asked Bou Meng if he had sworn an oath. Bou Meng replied, “The President didn’t have me swear an oath. I don’t know why and have wondered about this. All of the witnesses swear oaths. But not me. Perhaps the judges thought that I only tell the truth. It was only different for me.”Footnote 67 Bou Meng didn’t realize that civil parties don’t have to swear an oath before testifying.

At another point, Bou Meng said, “Let me tell you a story that illustrates that if you don’t tell the truth the Lord of the Iron Staff will make you have an accident.”Footnote 68 When Mam Nai, one of Duch’s top S-21 deputies, had testified, he had proclaimed his ignorance of and lack of involvement in the abuses, including the beating of Bou Meng. It was Mam Nai, Bou Meng testified, who had asked him to count the lashes he was being given.

After Mam Nai’s testimony, Bou Meng told me, Mam Nai’s son had picked him up and, perhaps a kilometer from the court, had a car accident. This was, Bou Meng surmised, a result of his swearing an oath to the neak ta and then lying in court. Bou Meng noted the moment when Kar Savuth suggested Bou Meng was not being fully honest with the court. “Last month,” Bou Meng recalled, “Kar Savuth questioned if my words were true. I replied ‘I have the Lord of the Iron Staff as my witness.’ If I had not been telling the truth, then I wouldn’t have sworn the oath.”

The truth of his statements, Bou Meng stated, was demonstrated by the fact that he had sworn to the neak ta that, if he were lying, he should be “hit and struck dead by a car. But I was not hit. Only the car of Mam Nai had a collision because he had not told the truth.”Footnote 69 Given his deep Buddhist beliefs, Bou Meng told the truth. He feared the karmic consequences of lying. This “bushy undergrowth” of Bou Meng’s understanding of the world and testifying in court, one in which Buddhism and animism were both highly salient, erupted for a moment in the “iron genie” translation, a slippage that passed by without much notice.

If Bou Meng’s invocation of the neak ta provides an illustration of a momentary slippage suggesting that something highly meaningful is being edited out of the juridical formation in-the-making, other slippages are directly in tension with this juridical formation despite being more apparent and interwoven into the proceedings. “Justice as desire” seeks to employ and order the narrative flow so that it accords with the victim–perpetrator binary naturalized in the transitional justice imaginary.

Within the frame of the court, Bou Meng’s subjectivity is appropriated into the category of victim, though one of a particular sort – a rights-invested liberal democratic victim subjectivity. This subjectivity was not the only one circulating in the court even if it predominated. There was also a Buddhist subjectivity that emerged at times, such as during Bou Meng’s references to how he wondered what bad acts he had done in the past that had led him to suffer so much at S-21. From this Buddhist perspective, the victim also bears a degree of blame since, by implication, one’s life is conditioned by one’s past acts. This Buddhist view on suffering is different than the liberal democratic one that was part of the juridical formation in-the-making, which assumes a victim’s blamelessness and innocence in contrast to the intentionality of the criminal perpetrator.

There is another manner in which Bou Meng’s testimony was in tension with this juridical subjectivity. As a legally recognized civil party and S-21 survivor, Bou Meng had victim status. His questioning proceeded along these lines, which constituted the borders of “the appropriate.” But his case and that of a number of S-21 victims and civil parties are not so simple since they were themselves Khmer Rouge – cadre and soldiers, perhaps at one time even perpetrators.

Bou Meng, for example, joined the revolution in the early 1970s, but this “grey zone” of his past was barely mentioned in court, in keeping with the “clipping” of the complicated geopolitical past. Thus, during his preliminary questioning of Bou Meng, President Non Nil asked, “Before the 17th of April 1975, where did you live and what was your occupation back then?” Bou Meng replied, “I went into the jungle to liberate the country and to save King Norodom Sihanouk.” Non Nil then immediately shifted the discussion to the temporal jurisdiction of the court, asking Bou Meng about his experiences from “April 1975 until the 7th of January 1979.”Footnote 70

Yet, this statement that Bou Meng had been a Khmer Rouge revolutionary passed by largely without comment. Judge Lavernge asked a few related questions, including one about the extent of Bou Meng’s devotion. Bou Meng replied, “I wore a black shirt, but my mind was not black. I did what I was instructed.”Footnote 71

Yet, if the other parties largely ignored Bou Meng’s past, the Defense did not. International Co-Defense Lawyer Canizares ended the day by seeking to establish a parallel between Bou Meng and Duch, whose defense partly centered around the idea that Duch had quickly become disillusioned with the revolution but had to reluctantly carry out his orders or be killed. Thus, Canizares asked Bou Meng about his lack of confidence in the regime and the necessity of nevertheless complying. Bou Meng affirmed this was the case. “[Was it] fear that made you follow 100 percent the orders that were given to you?” Canizares asked as she posed the final question of the day. Bou Meng replied, “In fact, that was the case.”Footnote 72

Here again we return to a doubleness that pervades the juridical process, as what is asserted as an ideal (the pure innocent victim) comes up against a more complex reality (the victim stained by association with the impure perpetrator category). This doubleness reveals an excess of meaning and a lack in the justice facade being asserted, one suggesting that “justice as deformation” is simultaneously taking place as alternative, complex local realities are clipped away and edited out by the disciplines of the court.