There are two environments in which spelling with <u> and <i> alternated in Latin orthography, with, on the whole, a movement from <u> to <i>, although in certain phonetic, morphological or lexical contexts the change in spelling either did not take place at all or took place at different rates. These environments are (1) original /u/ in initial syllables between /l/ and a labial; (2) vowels subject to weakening in non-initial open syllables before a labial. Both the question of the history and development of the spelling with <u> and <i>, and what sound exactly was represented by these letters is lengthy and tangled (especially with regard to the medial context; for recent discussion and further bibliography, see Suárez-Martínez 2006 and Reference WeissWeiss 2020: 584).

/u/ and /i/ in Initial Syllables after /l/ and before a Labial

In initial syllables we know on etymological grounds that the words in question had inherited /u/. In practice, there are very few Latin words which fulfil this context, and only two in which the variation is actually attested: basically just clupeus ~ clipeus ‘shield’ and lubet ~ libet ‘it is pleasing’ and its derivatives such as lubēns ~ libēns ‘willing’ (which is part of a dedicatory formula and makes up the majority of attestations of this verb), *lubitīna ~ libitīna ‘means for burial; funeral couch’, Lubitīna, Lubentīna ~ Libitīna ‘goddess of funerals’. No forms with <u> are found in liber ‘the inner bark of a tree; book’ < *lubh-ro-, whose earliest attestation is libreis in CIL 12.593 (45 BC, EDR165681), as well as being attested in literary texts from Plautus onwards. Strangely, lupus ‘wolf’ does not become ×lipus, as Reference LeumannLeumann (1977: 89) points out, although as it is attested in Plautus it was surely borrowed from a Sabellic language (as demonstrated by /p/ < *kw) early enough to have been affected.

As we shall see, both spellings are attested from the third century BC onwards in lub- and clupeus, with <u> predominating initially and slowly being replaced by <i>. Some scholars view this as a sound change from /u/ to /i/ (e.g. Reference WeissWeiss 2020: 153), others as the development of an allophone of /u/ to some sound such as [y], leading to variation in spelling with <u> and <i>, but with <i> eventually becoming standard (e.g. Meiser 1988: 80; making it more or less parallel with the development in non-initial syllables, which we shall discuss later).

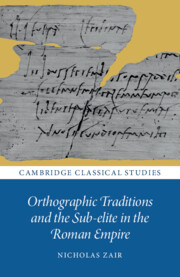

In epigraphy other than my corpora, the <i> spelling is attested early in the lub- words (see Table 3): libes (CIL 12.2867) for libēns is about the same time as the first instances of lubēns, but <u> outnumbers <i> by 13 (or 14, if CIL 12.1763 is to be dated early) to 3 in the third and second centuries BC. In the first century BC, however, there are only 4 (or 5 if CIL 12.1763 is to be dated later) instances of <u> to 4 of <i>, and subsequently <u>, with 2 instances in the first century AD (or 1 in the first, 1 in the second if CIL 3.2686 is to be dated late), is completely swamped: there are 16 (or 17 if CIL 5.5128 is to be dated early) instances of <i> in the first century AD, and in subsequent centuries the numbers are too massive to be included in the table.Footnote 1 These have not been thoroughly checked, and some are mere restorations, but the vast majority do indeed belong to the lexeme libēns.Footnote 2 Overall, then, it seems clear that the spelling with <i> was becoming more common in the course of the first century BC, becoming the usual spelling in the first century AD, and subsequently overwhelming the <u> spelling, although the latter is still occasionally found in the first, and perhaps second, century AD.

Table 3 lub- and lib- in inscriptions (omitting forms of libēns from AD 100)

| lub- | Inscription | Date | lib- | Inscription | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lubens | AE 2000.283 | 260–240 BC (EDR177325) | libe(n)s | CIL 12.2867 | 250–201 BC (EDR079096) |

| lub(en)s | CIL 12.62 | 270–230 BC (EDR110696) | lib(en)s | CIL 12.392 | End of the third century BC (Reference PeruzziPeruzzi 1962: 135–6) |

| lub(en)s | CIL 12.388 | Late third to second century BC (Reference Dupraz, Dupraz and SowaDupraz 2015: 260) | liben[s] | CIL 12.33 | 250–101 BC (EDR104811)Footnote a |

| lubens | AE 1985.378a | Towards the end of the third century BCFootnote b | libitinamue, libitina<m>ue | CIL 12.593 | 45 BC (EDR165681) |

| lubens | AE 1985.378b | Towards the end of the third century BC | libentes | CIL 12.1792 | 71–30 BC (EDR071934) |

| lubens | CIL 12.2869b | 270–201 BC (EDR079100) | libitin[ario], Libit(inae), libitinae, libit[inae | AE 1971.88 | Late first century BCFootnote c |

| lubens | AE 2016.372 | End of the second–start of the first century BC | libentes | CIL 8.26580 | Not long before AD 5 or 6 (Reference ThomassonThomasson 1996: 25) |

| lubens | CIL 12.28 | 225–175 BC (EDR102308) | libens | CIL 9.1456 | AD 11 (EDR167653) |

| lubens | CIL 12.29 | 230–171 BC (EDR161295) | libitinam | AE 1978.145 | AD 19 |

| lubent[es | CIL 12.364 | 200–171 (EDR157321) | libens | AE 1999.689 | Early decades of the first century AD |

| lubens | CIL 12.10 | 170–145 BC (EDR109039) | libens | CIL 6.68 | AD 1–30 (EDR161210) |

| lube(n)tes | CIL 12.1531 | 170–131 BC (EDR142283) | libentius | CIL 5.5050 | AD 46 (EDR137898) |

| lub[en]s | AE 2000.290 | 130–101 BC (EDR155416) | lib[iti]nar[io] | Reference CastagnettiCastagnetti (2012: 19) | AD 1–50 (EDR077677)Footnote d |

| lubens | CIL 14.2587 | 100–51 BC (EDR160891) | libens | CIL 14.2298 | AD 20–50 (EDR138163) |

| Lubitina | CIL 12.1268 | 100–50 BC (EDR126391) | libens | CIL 9.1702 | AD 1–70 (EDR102210) |

| [l]ubens | CIL 12.1763 | 150–1 BC (EDR072021) | libens | CIL 6.12652 | AD 14–70 (EDR108740) |

| lubens | CIL 12.1844 | 100–1 BC (EDR104237) | libenter | CIL 4.6892 | AD 1–79 (EDR125510) |

| Lubent(inae) | CIL 12.1411 | 50–1 BC (EDR071756) | libens | CIL 6.398 | AD 86 (EDR121358) |

| lubens | CIL 2.7.428 | Mid-first century AD | [l]iben[s] | AE 1986.426, 1988.823 | AD 1–100 (EDH, HD004388) |

| lubens | CIL 3.2686 | AD 1–150 (EDH, HD058450) | libe[ns] | CIL 5.17 | AD 1–100 (EDR135137) |

| libens (twice) | CIL 6.710 | AD 51–100 (EDR121389) | |||

| libens | AE 1988.86 | AD 51–100 | |||

| libens | CIL 14.2213 | AD 100 (EDR146713) | |||

| Libitinae | CIL 5.5128 | AD 51–125 (EDR092038) | |||

| libet | CIL 6.30114 | AD 101–200 (EDR130532) | |||

| libet | EDR171805 | AD 100–200 | |||

| cuilibet | CIL 5.8305 | AD 151–200 (EDR117525) | |||

| quibuslibet | CIL 3.12134 | AD 305–306 |

a Second century BC according to Grandinetti in Reference RomualdiRomualdi (2009: 150).

b But 170–100 BC on the basis of the palaeography according to EDR (EDR079779).

c Reference Hinard and DumontHinard and Dumont (2003: 29–35, 38, 49–51), on the basis of the spelling, language and historical context; similarly Reference CastagnettiCastagnetti (2012: 37–43).

d Not before the Augustan period, and prior to the change by Cumae from a municipium to a colonia in the second half of the first century, probably under Domitian (Reference CastagnettiCastagnetti 2012: 46–8).

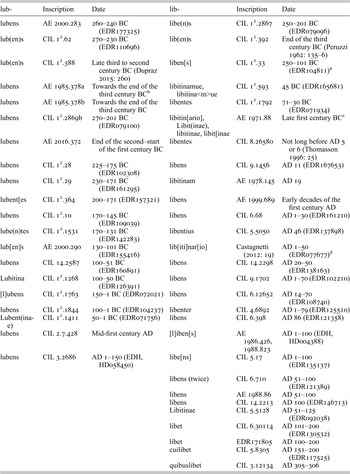

The spelling of clupeus ~ clipeus (Table 4) has a rather different profile: the lexeme is not found before the first century BC, when only the <u> spelling appears (2 or possibly 3 examples); in the first century AD there are 6–8 inscriptions which use <u>, but only 1–3 with <i> (and possibly quite late in the century), and still 4–5 <u> in the second century AD to 7 of <i>, with 1 <i> in the fourth.Footnote 3 It is perhaps surprising, given the common formulaic usage of lubens in dedicatory contexts, that clupeus appears to have retained the <u> spelling longer. Perhaps this is connected to the influence of the Res Gestae of Augustus.

Table 4 clupeus and clipeus

| clupeus | Inscription | Date | clipeus | Inscription | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| clupeum | AE 1952.165 | 26 BC | clipeum | CIL 9.2855 | AD 79–100 (EDR114839) |

| cḷup̣[eum] | CIL 6.40365 | 27 BC (EDR092852) | clipeis | CIL 2.5.629 | End of the first century or start of the second AD |

| clupeum | CIL 9.5811 | 25 BC–AD 25 (EDR015394) | clipeum | CIL 10.4761 | AD 1–200 (EDR174193) |

| clupeo | CIL 13.1041 | Augustan (CIL), AD 15–40 (EDCS-10401220) | clipeos | Reference IhmIhm (1899 no. 245) | AD 101–200 (EDR171383) |

| clupei | Res Gestae Diui Augusti (Reference ScheidScheid 2007; CIL 3, pp.769–99) | AD 14 | clipeos |

| AD 101–200 (EDR171384) |

| clupea | CIL 14.2794 | AD 50–51 (EDR154835) | clipeum | AE 1996.424b | AD 113 |

| clupeos | AE 1994.398 | AD 41–54 | [cl]ipeo | CIL 14.4555 | AD 172 (EDR072930) |

| clupeus | CIL 6.912 and 31200 | AD 23 (EDR105655) | clipeum | CIL 9.5177Footnote a | AD 172 (EDR135001) |

| clupeum | CIL 14.2215 | AD 1–100 (EDR146609) | clipeor(um) | CIL 9.2654 | AD 151–200 (EDR128138) |

| clupeum | AE 1934.152 | AD 71–200 (EDR073231) | clipe[u]m | AE 1948.24 | AD 191–192 (EDR073666) |

| clupei | CIL 11.3214 | AD 101–200 (EDR137358) | clipeos | ICVR 3.8132 | AD 366–384 (EDB24864) |

| clupeum | CIL 14.72 | AD 105 (EDR143920) | |||

| clupeum | CIL 9.2252 | AD 131–170 (EDCS-12401765) | |||

| clupeo | CIL 14.2410 | AD 158 (EDR155630) |

a CIL in fact gives the reading clupeum, but clipeum is correctly given by EDR135001 (a photo of the inscription can be found under the entry).

Unsurprisingly, given the restricted number of lexemes containing the requisite phonological environment, there are very few instances of this type of <u> spelling in the corpora. However, lubēns ~ libēns is used occasionally in letters at Vindolanda, where <i> outnumbers <u> 5 to 1. The sole use of <u>, in lụḅẹṇṭịṣsime (Tab. Vindol. 260), occurs in a letter whose author Justinus is probably a fellow prefect of Cerialis, and which the editors suggest may be written in his own hand, as it does not change for the final greeting. Towards the end of the first century AD, it seems fair to call this an old-fashioned spelling.

The examples of <i> are libenter (291, scribal portion of a letter from Severa), libenti (320, a scribe who also writes omịṣẹṛas, without old-fashioned <ss>), libente[r (340), libentissime (629; probably written by a scribe)Footnote 4 and ḷibent (640, whose author and recipient are probably civilians, and which also uses the possibly old-fashioned spelling ụbe).

The <u> spelling also occurs in a single instance in the Isola Sacra inscriptions (lubens, IS 223, towards the end of the reign of Hadrian or later). There is a good chance that this is the latest attested instance of the <u> spelling.The inscription is partly in hexameters, the spelling is entirely standard, and <k> is used not only in the place name Karthago but also in karina ‘ship’. Again, it is reasonable to assume that the <u> spelling in this word might be considered old-fashioned.

/u/ and /i/ in Medial Syllables before a Labial

The second context for <u> ~ <i> interchange is short vowels which were originally subject to vowel weakening before a labial. Hence we are not dealing only with original /u/ as is the case in initial syllables, and hence the subsequent development is not necessarily the same as in initial syllables.

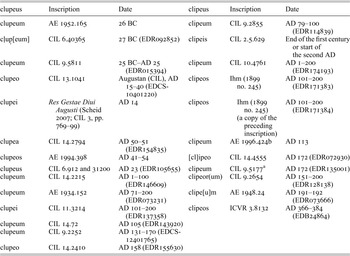

In order to utilise the evidence of the corpora it is necessary to first examine the highly complex evidence both of inscriptions and of the grammatical tradition, which descriptions in the literature such as Reference MeiserMeiser (1998: 68), Suárez-Martínez (2006) and Reference WeissWeiss (2020: 72, 128) tend to oversimplify.Footnote 5 Reference LeumannLeumann (1977: 87–90) provides a more comprehensive discussion. I will begin with the evidence of inscriptions down to the first century AD. In the first place, it is important to make a distinction which most of those writing about the <u> and <i> spellings do not make clearly enough. There are certain words in which the vowel before the labial was always written with <i> or <u> (as far as we can tell); presumably in these words the vowel had become identified with the phonemes /i/ or /u/ early on.Footnote 6 By comparison, there are some words in which the vowel before the labial shows variation in its spelling. The first instance of <i> before a labial is often attributed to infimo (CIL 12.584) in 117 BC (thus Reference NikitinaNikitina 2015: 19; Reference WeissWeiss 2020: 72), or testimo[niumque (CIL 12.583) in 123–122 BC (thus Reference Suárez-MartínezSuárez-Martínez 2016: 232). However, these are in fact the earliest examples of <i> in a word in which <i> and <u> variation is found. Probably earlier examples of the <i> spelling actually occur in opiparum ‘rich, sumptuous’ in CIL 12.364 (200–171 BC, EDR157321) and recipit ‘receives’ in CIL 12.10 (170–145 BC, EDR109039), for which a <u> spelling is never found.

In Table 5 I provide all examples of the use of <u> and <i> in this environment in some long official/legal texts of the late second century BC.Footnote 7 As can be seen, both spellings are found in these texts, but the distribution is not random. Most of the words with an <i> spelling never appear with a <u> spelling in all of Latin epigraphy: compound verbs in -cipiō,Footnote 8 -hibeō, -imō,Footnote 9 and forms of aedificium and aedificō,Footnote 10 uadimonium and municipium. Outside these particular texts, the same is true of pauimentum (CIL 12.694, 150–101 BC, EDR156830), animo (CIL 12.632, 125–100 BC, EDR104303). It looks as though by the (late) second century certain lexical items had already generalised a spelling with <i>.Footnote 11

Table 5 <u> and <i> in some second century BC inscriptions

| Inscription | Date | <u> | <i> |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIL 12.582 | 130–101 BC (EDR163413) | testumonium | accipito |

| recuperatores | |||

| proxsumeis × 3 | |||

| CIL 12.583 | 123–122 BC (EDR173504)Footnote a | aestumatio × 4 | |

| aestumandis × 2 | adimito | ||

| aestumare | testimo[niumque | ||

| aestumatam × 2 | |||

| aestumata × 2 | |||

| aest]umatae | |||

| exaestumauerit | |||

| uincensumo | |||

| proxum(eis) | |||

| proxumo | |||

| proxsumo | |||

| prox]umos | |||

| proxsumeis × 2 | |||

| maxume | |||

| plurumae | |||

| CIL 12.584 | 117 BC (EDR010862) | proxuma × 2 | ac(c)ipiant |

| Postumiam × 4 | prohibeto × 2 | ||

| infumum | eidib(us) | ||

| infumo × 2 | infimo | ||

| uicensumam | fruimino | ||

| CIL 12.585 | 111 BC (EDR169833) | optuma | aedificium × 6 |

| recuperatoresue | [a]edifi[cium] | ||

| r]ecuperatores | aedificio | ||

| recuperato[res | aed]ịf̣icio | ||

| recuperatorum | aedificii | ||

| recuperatoru[m | aedific[iei | ||

| maxsume | aedificiorum | ||

| mancup[is | aedificieis | ||

| proxsumo × 2 | uadimonium | ||

| proxsumeis × 4 | moi]nicipieis | ||

| proxumum | moinicipioue | ||

| decumas | moinicipieis | ||

| mancupuṃ | undecimam | ||

| CIL 12.2924 | 123–103 BC (EDR073760) | maxume | inhiber<e> |

a In fact EDR mistakenly gives the date as 123–112 BC.

By comparison, <u> spellings are found only in words which either show variation with <i> in the later period or which are subsequently always spelt with <i>,Footnote 12 such as testimonium, which across all of Roman epigraphy is found with the <u> spelling only in CIL 12.582.Footnote 13 The <u> spellings predominate in these words in these inscriptions: with <i> we have only infimo beside the far more common superlatives in <u>, the ordinal undecimam beside uicensumam, testimo[niumque beside testumonium, and eidib(us), which, as a u-stem, is also found spelt elsewhere with <u>.Footnote 14

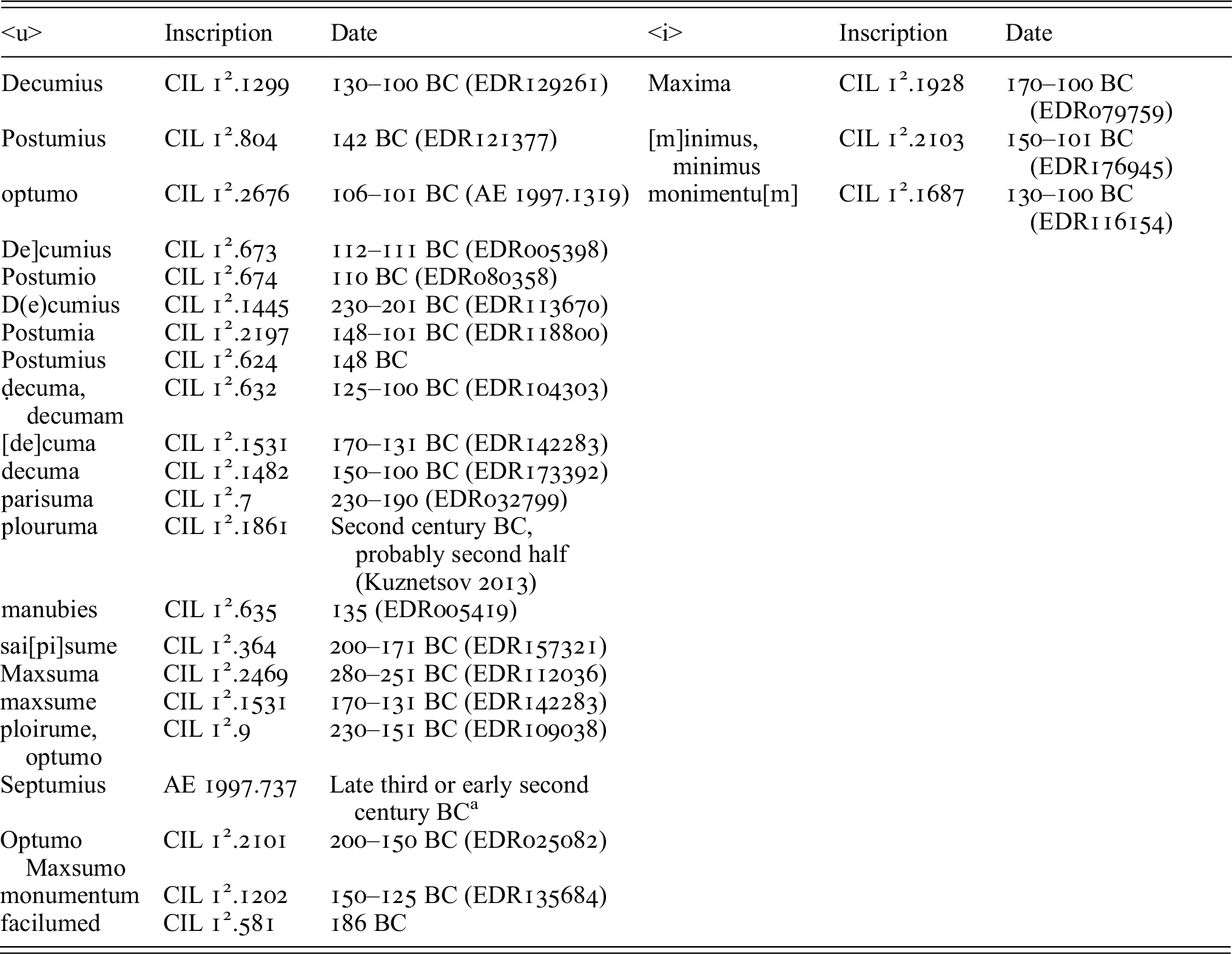

The same pattern is found in other inscriptions from the third and second centuries: in Table 6 I have collected all instances that I could find of <u> spellings in inscriptions given a date in EDCS, along with examples of <i> spellings of those words (other than those from CIL 12.582, 583, 584 and 585 and 2924). It seems clear that at this period the <u> spellings are dominant, although we do find a few <i> spellings (perhaps more towards the end of the second century). Nonetheless, all of these words do subsequently show <i> spellings (although the extent to which the <i> spelling is standard varies, as we shall see).

Table 6 Words with <u> spellings in the third and second centuries BC

| <u> | Inscription | Date | <i> | Inscription | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decumius | CIL 12.1299 | 130–100 BC (EDR129261) | Maxima | CIL 12.1928 | 170–100 BC (EDR079759) |

| Postumius | CIL 12.804 | 142 BC (EDR121377) | [m]inimus, minimus | CIL 12.2103 | 150–101 BC (EDR176945) |

| optumo | CIL 12.2676 | 106–101 BC (AE 1997.1319) | monimentu[m] | CIL 12.1687 | 130–100 BC (EDR116154) |

| De]cumius | CIL 12.673 | 112–111 BC (EDR005398) | |||

| Postumio | CIL 12.674 | 110 BC (EDR080358) | |||

| D(e)cumius | CIL 12.1445 | 230–201 BC (EDR113670) | |||

| Postumia | CIL 12.2197 | 148–101 BC (EDR118800) | |||

| Postumius | CIL 12.624 | 148 BC | |||

| ḍecuma, decumam | CIL 12.632 | 125–100 BC (EDR104303) | |||

| [de]cuma | CIL 12.1531 | 170–131 BC (EDR142283) | |||

| decuma | CIL 12.1482 | 150–100 BC (EDR173392) | |||

| parisuma | CIL 12.7 | 230–190 (EDR032799) | |||

| plouruma | CIL 12.1861 | Second century BC, probably second half (Reference KuznetsovKuznetsov 2013) | |||

| manubies | CIL 12.635 | 135 (EDR005419) | |||

| sai[pi]sume | CIL 12.364 | 200–171 BC (EDR157321) | |||

| Maxsuma | CIL 12.2469 | 280–251 BC (EDR112036) | |||

| maxsume | CIL 12.1531 | 170–131 BC (EDR142283) | |||

| ploirume, optumo | CIL 12.9 | 230–151 BC (EDR109038) | |||

| Septumius | AE 1997.737 | Late third or early second century BCFootnote a | |||

| Optumo Maxsumo | CIL 12.2101 | 200–150 BC (EDR025082) | |||

| monumentum | CIL 12.1202 | 150–125 BC (EDR135684) | |||

| facilumed | CIL 12.581 | 186 BC |

a Dated to the second century AD by Kropp (1.11.1/1), presumably by mistake.

Overall, the picture seems to be a much more complex one than simply a move from early <u> spellings to later <i> spellings.Footnote 15 Although <u> spellings outnumber <i> spellings in some words and morphological categories in the second century BC, certain words have already developed a fixed <i> spelling by this period, with no evidence to suggest that they were ever spelt with <u>. Most other words will go on to see <i> supplant <u> as the standard spelling, although at varying rates as we shall see, but some, like monumentum, postumus and contubernalis, will strongly maintain the <u> spelling.

For the later period, Reference NikitinaNikitina (2015: 10–48) examines the use of <u> and <i> in words which show variation in a corpus of legal texts and ‘official’ inscriptions from the first centuries BC and AD. In the legal texts, she finds only <u> down to about the mid-first century BC, after which <i> appears: in a few texts only <i> is attested, but many show both <u> and <i>. The lexeme proximus seems to be particularly likely to be spelt with <u>, perhaps due to its membership of the formulaic phrase (in) diebus proxumis. Even in AD 20, the two partial copies of the SC de Cn. Pisone patri (Reference Eck, Caballos and Fernández GómezEck et al. 1996) contain between them 24 separate <u> spellings and 2 <i> spellings, while CIL 2.1963, from AD 82–84, has 7 instances of <u> (5 in the lexeme proxumus), and none of <i>. There are only two ‘official’ inscriptions of the first century BC which contain words with <u> or <i> spellings, but in the other ‘official’ texts of the first century AD, <i> spellings are heavily favoured (73 examples in 25 inscriptions) over <u> spellings (8 examples across 4 inscriptions).

An interesting observation is that in the first century BC, superlatives in -issimus are often spelt with <u>. By comparison, in law texts of the first century AD, except in the SC de Cn Pisone patre, all 10 attested superlatives in -issimus have the <i> spelling, whereas the irregular forms like maximus, proximus, optimus etc. show variation. Although the switch between <u> and <i> in the -issimus superlatives is probably less abrupt than Nikitina perhaps implies,Footnote 16 it does seem likely that the <i> spelling became particularly common in this type of superlative around the Augustan period: as we shall see below, in imperial inscriptions <u> is used vanishingly seldom.

Nikitina’s study makes it clear that there was a movement from <u> spellings to <i> spellings in some words in high-register inscriptions over the course of the first century BC and first century AD. This movement probably took place more slowly in the more conservative legal texts,Footnote 17 and more quickly in certain lexical items (notably superlatives in -issimus) than in others.

If we turn to the evidence of the writers on language, the question of the spelling of these words was clearly one of great interest for some time.Footnote 18 Quintilian briefly mentions sounds for which no letter is available in the Latin alphabet, including the following comment:

medius est quidam u et i litterae sonus (non enim sic “optimum” dicimus ut “opimum”) …

There is a certain middle sound between the letter u and the letter i (for we do not say optĭmus as we say opīmus) …Footnote 19

This appears to imply that the vowel in this context was not the same as either of the sounds usually represented by <i> or <u>.Footnote 20 The spelling with <u> was however apparently ‘old-fashioned’ for Quintilian (at least in the words optimus and maximus):

iam “optimus” “maximus” ut mediam i litteram, quae veteribus u fuerat, acciperent, C. primum Caesaris in scriptione traditur factum.

C. Caesar is said in his writing to have first made optimus, maximus take i as their middle letter, as they now do, which had u among the ancients.

Cornutus (as preserved by Cassiodorus) appears also to think that the <u> is old-fashioned, and suggests that the spelling with <i> also more accurately reflects the sound. He gives as examples lacrima and maximus, as well as ‘other words like these’:

“‘lacrumae’ an ‘lacrimae’, ‘maxumus’ an ‘maximus’, et siqua similia sunt, quomodo scribi debent?” quaesitum est. Terentius Varro tradidit Caesarem per i eiusmodi uerba solitum esse enuntiare et scribere: inde propter auctoritatem tanti uiri consuetudinem factam. sed ego in antiquiorum multo libris, quam Gaius Caesar est, per u pleraque scripta inuenio, <ut> ‘optumus’, ‘intumus’, ‘pulcherrumus’, ‘lubido’, ‘dicundum’, ‘faciundum’, ‘maxume’, ‘monumentum’, ‘contumelia’, ‘minume’. melius tamen est ad enuntiandum et ad scribendum i litteram pro u ponere, in quod iam consuetudo inclinat.

“How should one write lacrumae or lacrimae, maximus or maximus, and other words like these?”, one asks. Terentius Varro claimed that Caesar used to both pronounce and write this type of word with i, and this became normal usage, following the authority of such a great man. What is more, I find many of these words written with u in books of writers much older than Gaius Caesar, as in optumus, intumus, pulcherrumus, lubido, dicundum, faciundum, maxume, monumentum, contumelia, minume.Footnote 21 However, it is better to both pronounce and write i rather than u, which is the way common usage is going now.

Velius Longus discusses the vowel in this context in several places. What he says about it provides an important caution against us assuming that the ancient writers on language thought, like us, that the words with <u> and <i> variation formed a single category for which a single rule was necessarily applicable. Instead, it seems likely that they looked at each word, or category of word, individually (an approach which accurately reflects usage, on the basis of the epigraphic evidence). Note that he also includes among his examples lubidō and clupeus (discussed above, pp. 75–82). The first passage which touches on this issue is a long and complex one:

‘i’ uero littera interdum exilis est, interdum pinguis, … ut iam in ambiguitatem cadat, utrum per ‘i’ quaedam debeant dici an per ‘u’, ut est ‘optumus’, ‘maxumus’. in quibus adnotandum antiquum sermonem plenioris soni fuisse et, ut ait Cicero, “rusticanum” atque illis fere placuisse per ‘u’ talia scribere et enuntia[ue]re. errauere autem grammatici qui putauerunt superlatiua <per> ‘u’ enuntiari. ut enim concedamus illis in ‘optimo’, in ‘maximo’, in ‘pulcherrimo’, in ‘iustissimo’, quid facient in his nominibus in quibus aeque manet eadem quaestio superlatione sublata, ‘manubiae’ an ‘manibiae’, ‘libido’ an ‘lubido’? nos uero, postquam exilitas sermonis delectare coepit, usque ‘i’ littera castigauimus illam pinguitudinem, non tamen ut plene ‘i’ litteram enuntiaremus. et concedamus talia nomina per ‘u’ scribere <iis> qui antiquorum uoluntates sequuntur, ne[c] tamen sic enuntient, quomodo scribunt.

The letter <i> is sometimes ‘slender’ and sometimes ‘full’, such that nowadays it is uncertain whether one ought to say certain words with i or u, as in optumus or maxumus. With regard to these words, it should be noted that the speech of the ancients had a fuller – and indeed rustic, as Cicero puts it – sound, and on the whole they liked to write and say u. But those grammarians who have thought that superlatives should be pronounced with u are wrong. Because, if we should concede to them with regard to optimus, maximus, pulcherrimus, and iustissimus, what will we do in words which are not superlatives, but in which the same question arises, such as manubiae or manibiae, libido or lubido? After we began to prize slenderness in speech, we went as far as to correct the fullness by using the letter <i>, but not so far as to give our pronunciation the full force of that letter. So let us permit those who want to follow the habits of the ancients in writing <u> to do so, but not to pronounce it how they write it.

My understanding of this passage is that Velius Longus is saying that the pronunciation of the words he discusses involves a sound which is not the same as the sound represented by <i> in other contexts, and is apparently ‘fuller’, but not as ‘full’ as it used to be, when <u> was a common spelling. Nowadays, the usual spelling is with <i>, but people who prefer to use the old-fashioned spelling <u> may do so. However, they should not extend this to actually pronouncing the sound as [u], because if they did, they would also by the same logic have to say [u] in words like manibiae and libidō. This final point is rather surprising. Does it suggest that by the early second century AD, the vowel of the first syllable of libidō had already developed to /i/, and hence a spelling pronunciation of [u] would sound wrong? Perhaps the same could be true of manibiae, if the development of the medial vowel before a labial was very sensitive to phonetic conditioning, such that here the pronunciation had again fallen together with /i/, unlike in the superlatives.

The following passage suggests that variation in both spelling and pronunciation still existed, with mancupium, aucupium and manubiae (again!) containing a sound which some produced in an old-fashioned ‘fuller’ manner and spelt with <u>, while others used a more modern and elegant ‘slender’ pronunciation, and wrote with <i>. Unlike in the previous passage, it is not explicitly stated here that the pronunciation of the relevant sound is different from /u/ and /i/.Footnote 22

uarie etiam scriptitatum est ‘mancupium’ ‘aucupium’ ‘manubiae’, siquidem C. Caesar per ‘i’ scripsit, ut apparet ex titulis ipsius, at Augustus [i] per ‘u’, ut testes sunt eius inscriptiones. et qui per ‘i’ scribunt … . item qui ‘aucupium’ per ‘u’ scribunt … sequitur igitur electio, utrumne per antiquum sonum, qui est pinguissimus et ‘u’ litteram occupabat, uelit quis enuntiare, an per hunc qui iam uidetur elegantior exilius, id est per ‘i’ litteram, has proferat uoces.

There is variation in how mancupium, aucupium and manubiae are written, since C. Caesar wrote them with i, as his inscriptions demonstrate, but Augustus with u, as his writings bear witness. And those who use i … Likewise those who use u to write aucupium … So it follows that it is a matter of choice whether one wants to use the old-fashioned sound, which is very full and is represented by u, or to pronounce these words using the more slender sound, which seems more elegant nowadays, that is, with the letter i.

The next four passages give examples of which letter to use in particular words which show variation: clipeus, aurifex, contimax and alimenta are better than the spellings with <u>, but aucupare, aucupium and aucupis are better than spellings with <i> (contradicting the previous passage with regard to aucupium). It is implied at 13.1.1 that the <u> spelling actually corresponds with a different pronunciation, but it may simply be as /u/.

idem puto et in ‘clipeo’ per ‘i’ scripto obseruandum, nec audiendam uanam grammaticorum differentiam, qui alterum a ‘clependo’, <alterum a ‘cluendo’> putant dictum.

I think the same thing [i.e. i for u] should also be observed in clipeus written with i, and we should not listen to the grammarians who set up an unnecessary distinction between clipeus, which they think comes from clependus, and clupeus from cluendus.

‘aurifex’ melius per ‘i’ sonat, quam per ‘u’. at ‘aucupare’ et ‘aucupium’ mihi rursus melius uidetur sonare per ‘u’ quam per ‘i’; et idem tamen ‘aucipis’ malo quam ‘aucupis’, quia scio sermonem et decori seruire et aurium uoluptate.

aurifex sounds better with i than with u. But aucupare and aucupium contrariwise to me seem to sound better with u rather than i; and likewise I prefer aucipis to aucupis, because I know that diction is subservient both to grace and to the pleasure of its hearers.

at in ‘contimaci’ melius puto ‘i’ servari: uenit enim a ‘contemnendo’, tametsi Nissus et ‘contumacem’ per ‘u’ putat posse dici a ‘tumore’.

But in contimax I think it is better to keep the ‘i’; for it comes from contemnendus, even if Nissus also thinks that contumax can be said, from tumor.

‘alimenta’ quoque per ‘i’ elegantius scribemus quam ‘alumenta’ per ‘u’.

We should also write alimenta with the more elegant i rather than alumenta with u.

Terentius Scaurus has little to add, except for some other examples of <u> and <i> interchange (in two of which, the dative/ablative plurals of the u-stems artus and manus, analogy with the rest of the paradigm is the cause of the continuing oscillation, as Scaurus goes on to note):

in uocalibus ergo quaeritur ‘maximus’ an ‘maxumus’, id est per ‘u’ an per ‘i’ debeat scribi; item ‘optimus’ et ‘optumus’, et ‘artibus’ et ‘artubus’, et ‘manibus’ et ‘manubus’.

Therefore amongst the vowels people wonder whether maximus ought to be spelt like this, with i, or as maxumus, with u; likewise optimus and optumus, and artibus and artubus, and manibus and manubus.

The fourth-century grammarians Diomedes and Donatus use almost exactly the same wording, no doubt due to reliance on the same source. They both imply that only <u> is used in optimus, but that it does not have the same sound as in other words:

hae etiam mediae dicuntur, quia in quibusdam dictionibus expressum sonum non habent, ut uir optumus.

These [i.e. i and u] are even called ‘middle’, because in certain words they are used even though they do not represent the sound which is actually pronounced, as in uir or optumus.

hae etiam mediae dicuntur, quia in quibusdam dictionibus expressum sonum non habent, i ut uir, u ut optumus.

These [i.e. i and u] are even called ‘middle’ vowels, because in certain words they are used even though they do not represent the sound which is actually pronounced, i as in uir, u as in optumus.

Marius Victorinus, although in the fourth century, suggests that optimus maximus is presently written with <u>, but that a number of other words, including maximus again, should be written with <i>, not <u>. This may be carelessness, or be due to differences in the sources that Marius Victorinus used. If we want to exculpate him of inconsistency, we might note that the sequence optimus maximus is a traditional epithet of Jupiter, in which the <u> spelling may have been maintained for longer than in maximus in other contexts.

idem ‘optimus maximus’ scripsit, non ut nos per u litteram.

The same man [Licinius Calvus] wrote optimus and maximus, not as we do using the letter u.

… sicut ‘acerrimus, existimat, extimus, intimus, maximus, minimus, manipretium, sonipes’ per i quam per u.

… in this way [we should write] acerrimus, existimat, extimus, intimus, maximus, minimus, manipretium, sonipes with i rather than with u.

The final passage contains various words in which Victorinus says that others have thought that they contain a sound between u and i, of which only proximus is relevant here. He suggests that in fact this sound is no longer used, and recommends a spelling either with <u> or <i>:

sunt qui inter u quoque et i litteras supputant deesse nobis uocem, sed pinguius quam i, exilius quam u <sonantem>. sed et pace eorum dixerim, non uident y litteram desiderari: sic enim ‘gylam, myserum, Sylla[ba]m, proxymum’, dicebant antiqui. sed nunc consuetudo paucorum hominum ita loquentium euanuit, ideoque uoces istas per u <uel per i> scribite.

There are those who think that we are lacking a letter for the sound which is between u and i, fuller than i but more slender than u. But with all due respect to them, I would say that they do not see that it is the letter y they want: for the ancients used to say gyla (for gula), myser (for miser), Sylla (for Sulla) and proxymus (for proximus).Footnote 23 But now this convention – which only a few men used in speech – has vanished, so you should write those words with u or i.

In dealing with these extracts from the writers on language of course the usual problem arises of to what extent the authors are reporting the situation in their own time, and to what extent they are reacting to spellings long out of use but still found in manuscripts and inscriptions, and passed down in grammatical writings. Nonetheless, it seems reasonable to me to deduce that even in the fourth century AD there were some people who used <u> in at least some words. However, Quintilian, Cornutus, Velius Longus, and to some extent Marius Victorinus, all imply that at least in some words this spelling was old-fashioned. On the basis of what Quintilian and Velius Longus say, there may have remained a sound not easily identifiable as /i/ or /u/ in some words into the second century AD (for more on the possible phonetic developments, see pp. 276–9).Footnote 24

If it is true that this sound continued in at least some words, it makes identifying old-fashioned spelling somewhat difficult. Since we do not know precisely at what point in a given word the sound became identified as /i/, continuations of the <u> spelling in words which are generally written with <i> may reflect an attempt to represent the sound as spoken, particularly if the writer has other substandard spellings, rather than knowledge of an older orthography, and this must be borne in mind when analysing the data.

We can now turn to the inscriptional evidence of the first to fourth centuries AD, and the use of the <u> spellings in the corpora. The lexicalised nature of the spellings with <u> or <i> makes it important that we do not assume that the spelling of all words containing the variation developed in the same way. This is also convenient, since it is difficult to carry out searches in the EDCS for sequences like ‘um’, ‘im’ etc. without including far too many false positives. I have therefore restricted searches to the words and categories which show variation in the corpora: these are largely the lexemes monumentum, contubernium and contubernalis, superlatives, and the ordinals septimus and decimus, and derivations thereof (including names).

I shall start with these last two categories. Very few superlatives in -issimus are found with <u> spellings in the epigraphy. I have found 39 inscriptions containing a <u> spelling in the first four centuries AD,Footnote 25 of which 1 is dated to the fourth century, 8 might be as late as the third, 19 as late as the second, and 11 are dated to the first century. This might suggest a general decline over time, although it would be necessary to know the frequency of superlatives in -issimus in these centuries to be sure of this (since in principle use of superlatives in general in inscriptions might have decreased over this period). In any century, however, the <u> spelling is clearly rare when compared with use of -issimus, which is found in thousands of inscriptions.Footnote 26 Combined with the evidence of a change in official inscriptions in the first century AD discussed above, it is reasonable to suppose that the standard spelling was <i>, and that the sound before the labial had become identified with /i/ in this morphological category.

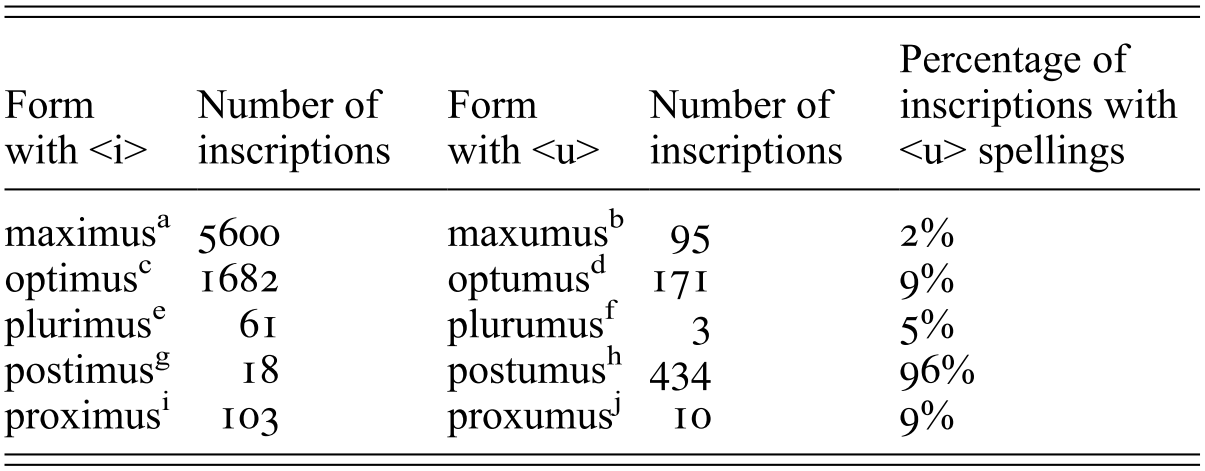

In other superlatives in -imus and words derived from them, the <u> spelling, while uncommon in all lexemes except postumus, is far more frequent than in -issimus superlatives (as we can see in Table 7).Footnote 27 Compared to the dominance of <u> spellings in the second century BC, it is clear that for most lexemes the <i> spelling becomes the standard in the imperial period, although to varying degrees. This may partly be because the sound before the labial remained different enough from /i/ to inspire <u> spellings for longer than in the -issimus superlatives. In postumus, conversely, it may at some point have been identified as /u/, but the (few) spellings with <i> suggest that this analysis was not inevitable: some people still heard a sound closer to /i/. A confounding factor is that several of these superlatives and their derivatives are very frequent as personal names; the same is true for ordinals: Septimus, Decimus, Postumus etc. It might be assumed that old-fashioned spellings are more likely to be preserved longer in names, but there is no easy way to search only for examples as names.

Table 7 <u> and <i> in superlatives in -imus

| Form with <i> | Number of inscriptions | Form with <u> | Number of inscriptions | Percentage of inscriptions with <u> spellings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| maximusFootnote a | 5600 | maxumusFootnote b | 95 | 2% |

| optimusFootnote c | 1682 | optumusFootnote d | 171 | 9% |

| plurimusFootnote e | 61 | plurumusFootnote f | 3 | 5% |

| postimusFootnote g | 18 | postumusFootnote h | 434 | 96% |

| proximusFootnote i | 103 | proxumusFootnote j | 10 | 9% |

a ‘maximu’ in the ‘original texts’ search, date range ‘1’ to ‘400’: 1502, ‘maximi’ 2021, ‘maximo’ 1452, ‘maxima’ 476, ‘maxime’ 73, ‘maxsimu’ 20, ‘maxsimi’ 26, ‘maxsimo’ 17, ‘maxsima’ 10, ‘maxsime’ 3 (26/04/2021).

b ‘maxumu’ in the ‘original texts’ search, date range ‘1’ to ‘400’ (20/04/2021): 34, ‘maxumi’ 12, ‘maxumo’ 18, ‘maxsumu’ 6, ‘maxsumi’ 8, ‘maxsumo’ 3, ‘maxsima’ 13, maxsume 1 (20/04/2021).

c ‘optimu’ in the ‘original texts’ search, date range ‘1’ to ‘400’: 90, ‘optimi’ 129, ‘optimo’ 980, ‘optima’ 399, ‘optime’ 84 (26/04/2021).

d ‘optum’ in the ‘original texts’ search, date range ‘1’ to ‘400’ (20/04/2021).

e ‘plurimu’ 8, ‘plurimi’ 9, ‘plurimo’ 11, ‘plurima’ 32, ‘plurime’ 1, date range ‘1’ to ‘400’ (26/04/2021).

f ‘plurum’ in the ‘original texts’ search, date range ‘1’ to ‘400’ (20/04/2021).

g ‘postim’ in the ‘original texts’ search, date range ‘1’ to ‘400’ (26/04/2021).

h ‘postum’ in the ‘original texts’ search, date range ‘1’ to ‘400’ (20/04/2021).

i ‘proximu’ 34, ‘proximi’ 13, ‘proximo’ 22, ‘proxima’ 26, ‘proxime’ 9, ‘proxsimi’ 0 (in fact 1, but in Kropp), ‘proxsimo’ 0, ‘proxsima’ 1, ‘proxsime’ 0 in the ‘original texts’ search, date range ‘1’ to ‘400’ (26/04/2021). I have removed from the count 2 instances in the TPSulp. tablets.

j ‘proxum’ 11, ‘proxsum’ 1 in the ‘original texts’ search, date range ‘1’ to ‘400’ (20/04/2021). I have removed from the count 2 instances in the TPSulp. tablets.

We also see a difference in the use of <u> and <i> in the ordinals in -imus: septimus is found in 1525 inscriptions, while septumus in only 83, given a rate of <u> of 5%; by comparison, decimus appears in 221 inscriptions and decumus 53, so that <u> is found in 19%.Footnote 28

On this basis, it is unclear at exactly what point use of <u> spellings in the corpora in these words, other than postumus, will have become old-fashioned rather than being a possible spelling for a living sound. Certainly not in the first century BC (e.g. Maxuma Kropp 1.7.2/1, optumos CEL 7.1.21, maxsuma CEL 10). However, the corpora tend to match quite well the distribution we see in the epigraphic record more generally. At Vindolanda, there are no examples of <u> spellings in 54 examples of superlatives in -issimus or 12 of superlatives and ordinals in -imus, and at Vindonissa 1 in -issimus and 1 in -imus (a name). At Dura Europos, 50 superlatives and ordinals in -imus (and -imius) are found, almost all the name Maximus. In the Isola Sacra inscriptions, 98 instances of this type are found with <i>, some names but the majority not; there is a single instance of <u> in the name Postumulene (IS 364). This consistent use of <i> rather than <u> is clearly not particularly remarkable.

In the curse tablets, there are a few examples of <u> spellings in names, where the spelling was probably maintained for longer: Septumius (Kropp 1.11.1/11, second century AD, Sicily), Postum[ianus] (3.2/77, third or fourth century AD, Britain), Maxsumus (5.1.4/10, first half of the second century AD, Germania Superior); likewise in the tablets of Caecilius Jucundus the names Postumi (CIL 4.3340.56, 74, 96) and Septumi (92) have <u> (there are no other examples of these names).

In the letters there is more variety, with three non-name instances of <u>. We find amicissumum (CEL 2, second half of the first century AD) in a very broken text apparently using a model letter of recommendation as a writing exercise. This is striking, since <u> is found so seldom in -issumus superlatives, and particularly so, since the same text apparently also includes an <i> spelling in plurị[mam]. The writer is not yet expert, going by the spelling Caesarre for Caesare. It seems likely that use of <u> was old-fashioned at this point, and the vowel had probably already merged with /i/ in -issimus by this period. Another damaged letter (CEL 166, around AD 150) has plúruma[m alongside the old-fashioned spelling epistolám (assuming this is not an early example of lowering of /u/; see pp. 66–71). The combination of the relative lateness, another old-fashioned spelling, and the fact that plurimus is written with <u> so rarely, suggest that this too is an old-fashioned spelling. On the other hand, this is far less clear for proxumo in a letter from one soldier to another dated to AD 27 (CEL 13). While this letter does have an old-fashioned spelling in tibei for tibi, proximus does seem to have maintained the <u> spelling for longer than the other superlatives, given the relatively high frequency of the <u> spelling for proximus seen at large, and Reference NikitinaNikitina’s (2015: 26–7) observation that this lexeme was particularly likely to maintain <u> in official inscriptions. So its use here may not be very old-fashioned. The writer’s spelling is otherwise standard.Footnote 29

In the tablets of the Sulpicii, we find <u> spellings in the epithets of Jupiter Optum<u>m, Maxumu, Optumum (TPSulp. 68), the first 2 by Eunus, the last by the scribe, where the <u> spelling is probably supported by tradition. And, again, we also have 2 other examples of <u> in pr[o]xum[e] (15) and prox]ume (19), both written by scribes. The same lexeme has the <i> spelling in proximas (87, 89), the former by a scribe, the latter not. Again, proximus show signs of having maintained its <u> spelling longer than some other words. Apart from these, the <i> spelling appears in duodecimum (45), uicẹṇsimum (46), the lexeme mancipium (85, twice, and 87, 3 times), and the perfect infinitive mancipasse (91, 92, 93), all written by scribes.Footnote 30 There are also 5 instances of the name Maximus (25, 50, twice, and 66, twice), of which 4 are written by a scribe.

Moving on to other lexemes, a curse tablet has alumen[tum] (Kropp 3.23/1, AD 150–200, Britain), which is found in two other inscriptions of the second century AD (alumentorum, AE 1977.179; alument[a]r(iae) CIL 9.3923= EDR175389).Footnote 31 This is therefore probably an old-fashioned spelling, since it compares with 98 inscriptions from the first to fourth centuries AD containing the <i> spelling (not to mention Velius Longus’ advice to use <i>),Footnote 32 although it is just possible that this word maintained a vowel for which <u> could be a plausible representation. Another has an<n>uuersariu (Kropp 1.4.1/1, c. AD 50, Minturno) for anniuersārium. No other examples of the <u> spelling are found, versus anniuersali (AE 1992.1771, AD 193–195, anniuersarium (CIL 6.31182, AD 101–200, EDR166509), anniuersaria (CIL 11, 05265, AD 333–337, EDR136860) and [ann]iuer[sarium (Res Gestae Diui Augusti; Reference ScheidScheid 2007; CIL 3, pp. 769–99, AD 14).

Lastly, a letter of the third century AD (CEL 220) has estumat for aestumat. I find no other instances of a <u> spelling, and no instances of the <i> spelling either, dated to the first four centuries AD in the EDCS, other than in the Lex Irnitana, which has both, but with <u> predominating (see fn. 17). In my corpora, aestimatum is found Dura Europos in a list of men and mounts (P. Dura 97.15, AD 251), and aestimaṭurụm in a copy of a letter sent by a procurator (P. Dura 66B/CEL 199.2, AD 221). If the vowel in the second syllable had not yet merged with /i/, estumat could be an attempt to represent the sound rather than an old-fashioned spelling, especially since the author has substandard <e> for <ae>.

Apart from these, fairly infrequent, examples, most words which are found with <u> in the corpora are those for which <u> seems to have been maintained as the standard spelling, i.e. monumentum, and contubernalis and contubernium. The evidence of the corpora provides an interesting hint that by the late first century or second century AD, use of <u> in these words was associated with writers whose orthographic education hewed closer to the standard and/or included old-fashioned features.

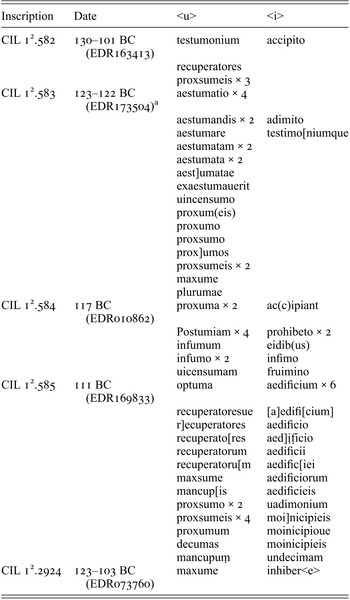

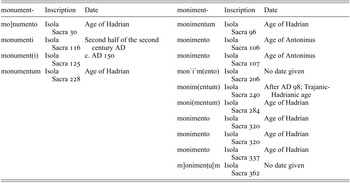

The Isola Sacra inscriptions, being funerary in nature, are the only corpus to include monumentum (see Table 8). There are 4 instances spelt with <u> and 10 with <i>, a reversal of the pattern in all of first–fourth century AD epigraphy, in which <u> spellings make up nearly two thirds of the examples, with 420 dated inscriptions, while the <i> spelling is found in 240.Footnote 33 There is no evidence that <u> is used in earlier inscriptions than <i>.

Table 8 monumentum and monimentum in the Isola Sacra inscriptions

| monument- | Inscription | Date | moniment- | Inscription | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mo]numento | Isola Sacra 30 | Age of Hadrian | monimentum | Isola Sacra 96 | Age of Hadrian |

| monumenti | Isola Sacra 116 | Second half of the second century AD | monimento | Isola Sacra 106 | Age of Antoninus |

| monument(i) | Isola Sacra 125 | c. AD 150 | monimento | Isola Sacra 107 | Age of Antoninus |

| monumentum | Isola Sacra 228 | Age of Hadrian | mon`i´m(ento) | Isola Sacra 206 | No date given |

| monim(entum) | Isola Sacra 240 | After AD 98; Trajanic-Hadrianic age | |||

| moni(mentum) | Isola Sacra 284 | Age of Hadrian | |||

| monimento | Isola Sacra 320 | Age of Hadrian | |||

| monimento | Isola Sacra 320 | Age of Hadrian | |||

| monimento | Isola Sacra 337 | Age of Hadrian | |||

| m]onimenṭu[m | Isola Sacra 362 | No date given |

It is possible that there is a correlation between use of monimentum and substandard spelling. The inscriptions with the <u> spelling use an orthography which is otherwise standard, with the exception of filis for filiīs in 228; the stonemason has also made several mistakes in the lettering, so an accidental omission of an <i> is also possible. All but 228 also feature Greek names containing either <y> or aspirates which are spelt correctly. However, the text of IS 30 is very damaged. By comparison, of the inscriptions containing monimentum, 206 has Procla for Procula, preter for praeter and que for quae; 284 also has filis for filiīs; 320 has que for quae, 337 has mea for meam and nominae for nōmine (both may be stonemason’s mistakes, however; see pp. 62–3), and sibe for sibi (on which, see pp. 59–64). 106 and 107 have Ennuchis for Ennychis, 337 Afrodisius for Aphrodisius (Agathangelus and Tyche are spelt correctly in 240; Polytimus, Polytimo and Thallus in 284; and Zmyrnae in 320). None of these inscriptions, even those which use the <u> spelling, features any other old-fashioned spellings (e.g. <c> rather than <k> before<a> in cari[ssimae, IS 30, huius with single <i>, IS 125). While not being conclusive evidence, all this would be consistent with the possibility that monumentum was the standard spelling at this period, and that monimentum was substandard.Footnote 34

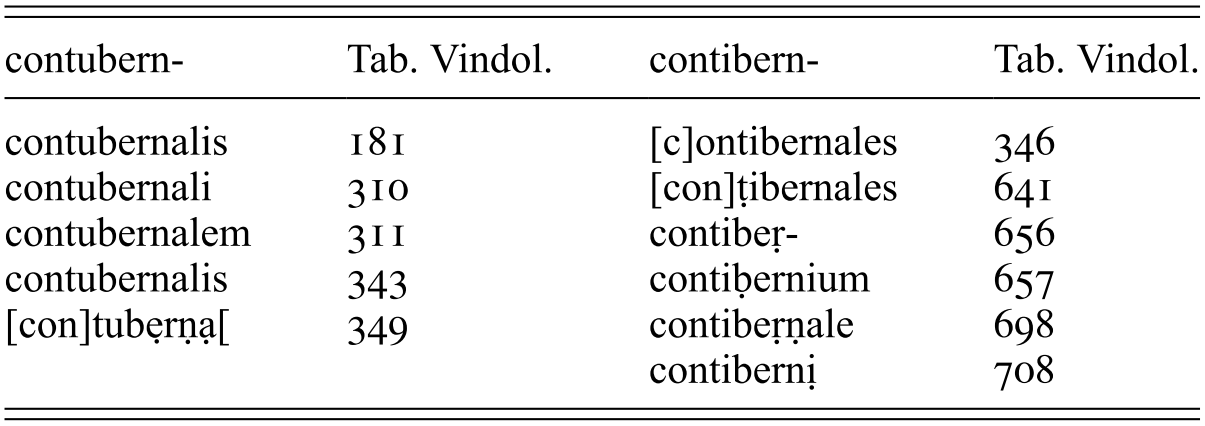

A search on the EDCS finds 433 inscriptions containing contubernium and contubernālis in the first four centuries AD, and only 17 with contibernālis (there were no examples of contibernium).Footnote 35 The earliest dated example found for contibernālis is contibernali (AE 1975.226), from between 31 BC and AD 30 (EDR076061), although the earliest examples of contubernālis are not necessarily much earlier: contubernal(i) (CIL 6.39697, 50–1 BC, EDR072515) and contubernali (CIL 5.1801, Augustan period). It seems, therefore, that the spelling of these words with <u> is not old-fashioned in terms of usage: it remained current throughout the imperial period and was apparently never replaced by the <i> spelling in standard orthography. The epigraphic evidence does not even allow us to be certain that the <u> spelling is the older spelling.

Table 9 contubernalis and contibernalis in the Vindolanda tablets

| contubern- | Tab. Vindol. | contibern- | Tab. Vindol. |

|---|---|---|---|

| contubernalis | 181 | [c]ontibernales | 346 |

| contubernali | 310 | [con]ṭibernales | 641 |

| contubernalem | 311 | contibeṛ- | 656 |

| contubernalis | 343 | contiḅernium | 657 |

| [con]tubẹrṇạ[ | 349 | contibeṛṇale | 698 |

| contibernị | 708 |

For the spelling of this word in the Vindolanda tablets see Table 9. The <u> spelling in this word is used by the writer of 181, who also wrote 180 and 344; the author was a civilian, and the writer of these texts also uses <ss> and <xs> (see p. 263) as well as some substandard spellings. 310 is the letter of Chrauttius, whose scribe also uses <ss>. 311 is written by a scribe who also uses apices. 343 is the letter whose author is Octavius, possibly a civilian, and which combines use of <xs>, <ss> and <k> with a number of substandard spellings. 349 is a fragmentary letter, presumably written by a scribe. It includes an instance of <x>. Note that two of these texts also include superlatives spelt with <i>: felicissimus (310), plurimam, inpientissime (311).

The <i> spelling is used by the writer of the letters 346, 656, 657, and perhaps also the fragmentary 708, presumably a scribe. The spelling is entirely standard (n.b. solearum twice at 346, not soliarum). In 655 the same writer has misi rather than missi, and in 657 <x> rather than <xs>. The writer of 641, a letter, is presumably also written a scribe. It contains misi and an example of <x>. 698 is too fragmentary to say anything about. The number of instances of <i> is surprising, but less striking when we observe that 4 out of 6 (probably) belong to the same writer. All instances of <i> are likely to belong to scribes, whereas <u> is used both by scribes, and, possibly, civilian writers. The use of <u> may correlate with the other old-fashioned spellings <ss>, <xs>, and <k> – but also substandard spellings.

The <u> spelling of contubernalis is found also in the letters of Tiberianus (P. Mich. VIII 467.35/CEL 141), which features some old-fashioned spelling (<uo> for /wu/, <k> before <a>), and some substandard features, although the spelling is overall closer to the standard than some of the letters in this archive.Footnote 36 This combination leads Reference Halla-aho, Solin, Leiwo and Halla-ahoHalla-aho (2003: 248) to suggest that the writer was ‘a military scribe, trained to write documents for the military bureaucracy’. This letter also provides evidence for the independence of <u>/<i> spellings across lexemes: it includes plurimam, optime, optimas, libenter.

The <u> spelling is also found in an early private letter (contubernálés, CEL 8, 24–21 BC), which has completely standard spelling (apart possibly from Nìreo for Nēreō, see p. 209 fn. 6), and also includes ualdissime. A much later letter has c]ọn[t]ubernio (CEL 220, third century AD), and has estumat for aestimat (see above). The use of <e> for <ae> in the latter is substandard; we do not have enough evidence to be sure that <u> is old-fashioned.