‘Ao!’ the elderly woman exclaimed, squinting with contempt. ‘Does this person have no manners? Doesn’t she know she should greet us by saying dumelang, batsadi [hello, my parents]?’

It was early evening and shadows were lengthening across the dusty lelwapa, the low-walled courtyard huddled between the small houses of the yard. The old woman sat on stitched-together sacks laid on the smooth cement stoep, her back against the wall of the main house, where the shadows were deepest and coolest. I had a passing familiarity with the yard from beyond its fence line, but had just entered it for the first time, mumbling a shy dumelang – hello. The simple greeting was about the limit of my Setswana; I could scarcely understand the old woman’s reprimand. But I could tell I’d already messed up somehow. I stood there, bewildered, and said nothing.

‘Hei! You, old woman, do you speak English?’ A woman about my age, perched on the low courtyard wall, came unexpectedly to my defence. ‘Why should you expect this one to know Setswana?’ The elderly woman looked grudgingly at the younger – her daughter, it later turned out. Then she shot me a surly look and harrumphed. A child emerged from the house, carrying a plastic chair, and set it down next to me, her eyes wide. I glanced around, uncertain what had been said; I hadn’t planned to stay. The woman who had defended me nodded at the chair. I sat down. We all remained silent.

I had come on an awkward errand. I knew the older woman’s teenage granddaughter, Lorato,Footnote 1 from the local orphan care centre, where I was a volunteer. I knew her son Kagiso, who worked at the project, too. I had often walked Lorato and her friends home from the centre as far as their respective gates, and they frequently came to visit me when the project was closed, sometimes staying to eat or to help around the house. Lorato and her friends had helped make me feel at home in the village in those first months of my life there, showing me its shortcuts, sharing its rumours and dramas, laughing at my confusions and mistakes. But I knew very little about their families. Generic stories circulated at the centre: accounts of caregivers making their orphaned charges take on unfair amounts of work around the house, refusing to buy them clothes or toiletries, treating them differently from the other children of the yard. My visit that day was the first time I had met one of these families in person – and the circumstances did not seem to bode well.

A few days previously, I had seen Lorato’s grandmother standing outside the tall fence that surrounded the centre, yelling across its open playing areas at some volunteers in the yard. She had sounded aggrieved and angry. I asked someone what she had said, and was told that she was insisting that the lot of us were attempting to ruin her family. No one responded to her directly, nor did they invite her in or ask about what had happened or what her specific concerns were. They stood where they were, listening but not getting involved, until she finished what she had to say and went home. But the allegation had been serious.

‘Haish, ke kgang,’ a friend at the project commented wearily, telling me about the incident afterwards: this is a problem. He had a degree in social work, and explained that her complaint was the sort that could have the organisation called in front of the kgotla, the village tribal administration and customary court. It wasn’t the first time the organisation had fallen foul of families in the village. But the management was haphazard in its approach to such misunderstandings, often leaving it to staff and volunteers to orchestrate compromises. My friend suggested that, as the volunteer closest to Lorato, I should pay her family a visit. ‘Get inside the gate,’ he specified. ‘Otherwise that old woman will be even more insulted.’

That first visit, in the gathering summer of 2004, was brief and uncomfortable. When Lorato translated the exchange for me later, I thought it odd that her grandmother – whom I call Mmapula – should insist that I call her ‘parent’, especially given her evident displeasure with me and the organisation in which I worked. I assumed it was a generic means of demanding respect from one’s juniors. But in the years that followed, no one else ever required it of me quite the way Mmapula had. She was being both deliberate and literal in ways I could not have anticipated.

A few days after my initial visit, Mmapula visited the centre in person to request my help in guiding Lorato’s behaviour there and at home, where she had begun to shirk her responsibilities. I was taken aback by the request, but agreed to have a talk with the young woman. Thereafter, I began to visit the family – the Legaes – on occasion, at first just to sit awkwardly with them, later to chat a little or play with the children. Then Lorato’s aunts began visiting me, often bringing the children with them, especially on their way out to or back from ‘the lands’, as they called the fields the family ploughed outside the village. In time, I was invited to go with them and help with the harvest. Later, we would venture farther afield, as they invited me to attend weddings and funerals with them. The older children were sent to stay with me during their exams or to help me at home. I began to wonder whether, at our first meeting, Mmapula had been making a specific claim on me: whether she was demanding acknowledgement and respect as Lorato’s parent in her own right, but also drawing me into a web of obligations by claiming recognition as my parent, too. Either way, we both gradually came to take that claim seriously – and it defined the terms on which I was drawn into social life in Botswana.

In late 2005, I moved from the orphan care project to a job with Botswana’s Department of Social Services, coordinating non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that served children orphaned by Botswana’s AIDS pandemic around the country. At the same time, drawing on my time with the Legaes, I began to question the discourses that dominated the NGO and government spheres in which I worked: of the neglect and abuse of orphaned children, and of inevitable family breakdown in the face of AIDS. My experience with the Legae family – unquestionably impacted but by no means destroyed by the epidemic – made me question the effects of AIDS on families, as well as the rationales and legacies of government and non-governmental interventions launched in response. Those questions shaped my personal and professional life until I left Botswana in 2008, and they took me back three years later to undertake the research project on which this book is based.

This book gives an ethnographic account of Tswana family life in a time of rapid socio-political change, epidemic disease, and unprecedented intervention on the part of governmental and non-governmental agencies. It is grounded in the everyday experience of one family – the Legaes – but draws in the interlinked lives of neighbours, friends, workmates, and churchmates, as well as the social workers, NGO staff, and volunteers who live and work among them. It traces the dense, shifting relationships of a single extended household, but also the unexpected ways in which these relationships entangle and bind together a village and a district, and extend right across the country. It also challenges the widespread assumption – common to humanitarian, development, and public health interventions in Botswana, to government and non-governmental programmes, and to representations in the country’s media – that AIDS has destroyed families by showing how crisis creates, recalibrates, and reproduces kin relations among the Tswana. And it argues that government and NGO agencies that intervene in families during times of crisis – often in relevant, culturally appropriate ways, but with quite different notions of crisis and how it ought to be addressed – may be having more lasting, deleterious effects on families than the epidemic itself.

Each of the following chapters engages with ways in which the Tswana make family: from living, eating, and working together to managing a household and contributing to one another’s care; from forming intimate relationships to bearing and raising children and negotiating marriage; from coming of age to holding parties and burying the dead. I argue that every one of these processes simultaneously produces risk, conflict, and crisis, which I have glossed with the Setswana term dikgang (sing. kgang). These dikgang need constantly to be addressed in the right ways by the right people; who ought to address what and how is not simply prescribed by age, generation, and gender, but establishes relative authority and reworks familial relationships. Dikgang are seldom, if ever, fully resolved; negotiations are fraught and uncertain and may escalate misunderstandings or introduce new conflicts, while solutions are often tacit or suspended. But their aim is not to resolve problems so much as to engage those involved in an ethical process of reflecting on the ways they affect one another, the quality and history of their relationships. Tswana kinship, in other words, is generated and experienced as a continuous cycle of conflict, mediation, and irresolution; it creates crisis – and to some extent thrives on it. In this sense, dikgang do not mark breakdowns in or failures of kinship; they are a critical means of constituting and sustaining family. In a structurally fluid kinship system like that of the Tswana (to which I return below), the ongoing negotiation of dikgang charts the limits of kin relations, defines different modes of relatedness within those limits, and establishes specific interdependencies and distinctions between the familial and the extrafamilial as well.Footnote 2 Dikgang draw our attention to the surprisingly effective ways in which families respond to crises like the AIDS epidemic, creatively accommodating the change crisis brings while simultaneously asserting continuity.

The unexpected family-making effects of crisis among the Tswana encourage us to rethink kinship broadly, as an ideal and in practice. I suggest that kinship may be best understood as something that straddles a series of competing – even opposed – relational, ethical, and practical imperatives. In Botswana and beyond, families are expected to persist indefinitely, while accommodating both massive socio-political change and the tumultuous upheavals involved as family members attain new roles or new status, as new relationships are incorporated, or as generational roles and responsibilities shift over time. In many contexts, families are idealised as sources of intimacy and belonging – although that intimacy brings unique risks and there is danger or flux in that belonging. At the same time, families must find ways to create distance sufficient to reconfigure their relationships and incorporate their own growth and reproduction. Families work to include and exclude (sometimes the same people), to share and separate, to display and conceal; they are oriented simultaneously to histories and futures that are both domestic and political, public and private. Being family requires a delicate balance to be sought between these and many other contradictory and mutually unsettling demands; but that balance is elusive and easily upset, and needs continuous recalibrating. Conflict and crisis, I argue, emerge when the balance is off-kilter and the paradoxes most prominent; reflexive efforts at negotiating and addressing conflict are one ongoing means of recalibration. Conflict, in this sense, is not simply an unfortunate exception to a general rule of kinship harmony; it is a key factor in the flexibility, persistence, and specificity of kinship as lived experience. While this book explores the unique tensions arising in Tswana kinship structure and practice, it also invites comparison with similar tensions in other contexts; and it proposes conflict as one way of rethinking kinship in potentially global, comparative terms.

My appearance in the Legae household in response to kgang, and as an object of kgang myself, foreshadows a linked trend with which this book is concerned: the widespread involvement of governmental, non-governmental, and transnational agencies in the Tswana family, an involvement that has increased sharply since the start of Botswana’s AIDS epidemic. Dikgang mark the points at which, and shed light on the rationales and ethics by which, organisations intervene in families. The programmes these organisations run – commonly conceptualised and delivered by Batswana, if often funded by foreign donors – are frequently well-aligned with the needs and practices of the families they serve, partially embedding institutions and practitioners in networks of kin. But their dominant approaches to dikgang – as problems requiring definitive solutions, best offered by professionals – diverge significantly from familial logics. This divergence creates new, volatile dikgang, involving a wider and more unpredictable range of actors, and novel, opaque frameworks for the reflexive assessment of what dikgang mean. In their scope, complexity, and ethical repertoire, these new dikgang often complicate and undermine the family’s usual means of response. The partial embeddedness that makes agencies effective, then, also makes them a risk – and the sort of risk they present exacerbates the conflicts and crises families already face, undermining the support these agencies seek to provide. Gradually, these new dikgang rework relationships among kin and between the home, the village, and the morafe (tribal polity). Dikgang, in this sense, mark key ways in which the spheres of kinship and politics are linked, and describe the work by which they are distinguished and their relationships managed by families and agencies alike.

Families in Botswana interact with a vast array of organisations, ranging from the governmental through the non-governmental to the informal: from clinics and schools to police and the customary court or kgotla; from government agencies for water, agriculture, or land to churches of many denominations; from support groups and home-based care projects to rights advocates and development projects; from burial societies and small-scale savings groups to choirs and dance or drama groups. The breadth of government programmes is substantial, and they play a significant role in many people’s lives – whether by providing local development opportunities or old-age pensions, agricultural subsidies or destitution relief, pre-school places or post office-based banking services. NGOs offer nearly as wide a range of services, sometimes in partnership with government. While the arguments I set out about dikgang could be made for any of these programmes or interventions, I focus on two that have become especially influential in Botswana’s time of AIDS: orphan care projects (run by NGOs) and social work offices. I spent over four years working with both types of organisation before undertaking this research. In that time, I became sharply aware of how unpredictable their programming could be in its effects – much to the frustration of the highly qualified, experienced, and dedicated Batswana who deliver it. In this book, I trace those mixed results: first, to divergent understandings and interpretations of dikgang; and then to a subtler but deeper tension between conflicting expectations, experiences, and practices of kinship that animate the work of these agencies. I suggest that NGOs and social work offices working with families operate with specific, conflicting, and inexplicit visions of what families ought to be like; and, in many ways, they work like conflicted families themselves. They also work within larger political projects for which these kinship orientations are crucial means of depoliticising, naturalising, and reproducing power. But the family-like processes and ideals by which these organisations are animated are simultaneously Tswana, British, American, European, and so on – reflecting the range of family models that underpin professional training, benchmarking, ‘best practice’, international guidelines, and donor funding regimes. This profusion of kinships – mutually recognisable but disparate and carefully obscured – complicates the effects of practitioners’ everyday work and undermines the political projects within which they are embedded. In the following chapters, I give an account of orphan care centres and social work offices that draws out the ‘persistent life of kinship’ (McKinnon and Cannell Reference McKinnon, Cannell, McKinnon and Cannell2013) in their work and traces its effects as an unruly, disruptive force that collapses distinctions between the familial and the political in unpredictable ways.

In this introduction, I situate these arguments first in the context of Botswana, and then in broader anthropological conversations around kinship and crisis, humanitarian and development intervention, and HIV and AIDS. I then explore the ethical and methodological questions that emerge in studying dikgang, both by being family and in NGO and governmental interventions. Finally, I provide a summary of the chapters to follow.

Botswana: A Potted History

Botswana is a landlocked, sparsely populated country in the heart of Southern Africa, which takes pride in an international reputation for peace, stability, and good governance. It has become commonplace to describe the country as ‘Africa’s miracle’, especially in light of its rapid rise to prosperity after achieving independence from Britain in 1966 and the discovery of diamonds (see Mogalakwe and Nyamnjoh Reference Mogalakwe2017: 2 for an overview of the case made for its exceptionalism). And yet Botswana has struggled persistently with some of the highest rates of HIV infection in the world (UNAIDS 2021) – an apparent anomaly in its otherwise auspicious record. The unusual combination of a stable government and economy, evident political will, and a disastrous epidemic has drawn floods of resources into the country for over three decades: funds, personnel, infrastructure, organisations, and programmes of every stripe. In that time, Botswana has produced responses to AIDS that are globally recognised as ‘best practice’, including the free public provision of antiretroviral treatment (UNAIDS 2003). Still, new infection rates remain high for the region, and the prevalence of HIV among adults remains near 20 per cent (UNAIDS 2020). In this section, I provide a brief historical background to contextualise this ostensible conundrum, and set the scene for the analytical themes through which I approach it.

Botswana’s relative success is often linked to the unique circumstances of its colonisation. Aware of Cecil Rhodes’ ambitions in the region, the dispossession of chiefs, and the violent maltreatment of their people that occurred under the auspices of the British South Africa Company (BSAC) in South Africa and Rhodesia, the paramount chiefs of the three most powerful merafe (tribal polities) in what is now Botswana chose a novel approach. In 1895, the Three Dikgosi (chiefs), as they were to be known later, travelled to England in the company of missionaries from the London Missionary Society. They made a request to Joseph Chamberlain, then Colonial Secretary, that Bechuanaland be made a protectorate of the British Empire, governed directly from London rather than by Rhodes’ BSAC. When Chamberlain refused, the chiefs undertook a highly successful tour of England, campaigning in churches and at public events. They garnered the support of temperance, anti-slavery, and humanitarian groups and of many of the churches, which in turn lobbied Chamberlain to reconsider his position. Concerned that it might become an election issue, he did reconsider – on the condition that the chiefs cede the land necessary for Rhodes’ railway and that they accept the introduction of taxes (Sillery Reference Sillery1974; Tlou and Campbell Reference Tlou and Campbell1984).

Bechuanaland was ruled indirectly, from Mafeking in present-day South Africa, and was governed in large part as a labour reserve for its southern neighbour (Parsons Reference Parry and Bloch1984) – a role it continued to play well beyond its eventual independence in 1966. The British colonial government invested minimally in administering the protectorate and famously left the country with only seven kilometres of tarred road and a capital – Gaborone – with little more than a railway station. And yet the legacy of colonisation, and of the ambitious missionisation that preceded it, is evident everywhere: in Botswana’s government structures, in its parallel systems of customary and common law, in the disappearance of initiation rites, in changes to bridewealth payments, and in much of its education, health, and social welfare provision (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1991; Griffiths Reference Griffiths1997; Schapera Reference Schapera1933; Reference Schapera1940; Reference Schapera1970). Nonetheless, the strategic foresight of the Three Chiefs, combined with the impression that Bechuanaland was little more than an arid desert, spared the nascent nation some of the more egregious violence, rapacious resource stripping, and racist political landscaping that characterised the experience of other colonies in the region. Batswana generally hold the intervention of the Three Chiefs as a defining moment in the history of the nation; one of the country’s few monuments, The Three Dikgosi, was raised to them. The influential role of churches and humanitarian groups in this tale speaks to the long-term involvement of international civil society in the country’s political and social life, dating back to a period well before the current spate of NGO programmes.

At independence in 1966, Botswana was one of the poorest countries in the world, considered a ‘hopeless basket case’ (Colclough and McCarthy Reference Colclough and McCarthy1980). However, diamonds were discovered within a year, and the country’s fortunes changed rapidly. Botswana is currently the world’s largest producer of diamonds by value (Krawitz Reference Krawitz2013) – although it is only in recent years that the value-added aspects of sorting and polishing have been kept within the country. The diamond industry, overseen by the government in partnership with De Beers, has allowed Botswana to take a strongly state-led – and highly successful – approach to development (Taylor Reference Taylor, Poku and Whiteside2004: 53–4). Roads, schools, and clinics have been built and staffed countrywide, and a wide range of social welfare schemes have been introduced, from old-age pensions to drought relief. Until the global economic downturn of 2007–2009, Botswana’s diamond revenues were sufficient for the country to avoid dealings with the World Bank or International Monetary Fund altogether, and thereby sidestep the economic and political legacies of insupportable debt and structural adjustment that have plagued many other African countries since the 1980s. Botswana is currently ranked a middle-income country by the World Bank.

At the same time, for decades Botswana has routinely been in the top echelon of countries globally for income inequality. In 2020, it was listed as the fourth most unequal country in the world in terms of income distribution (World Population Review 2020). Domestic rates of employment have improved since the era of labour migration, but job opportunities remain limited, with unemployment rates averaging around 18 per cent over the past three decades (CEIC 2019). While the economy has diversified around tourism and beef exports, it remains heavily dependent on diamonds – a fact brought home during the financial crisis, when diamond markets collapsed. Many Batswana – including the Legaes – continue to rely on subsistence farming, a tenuous business in a place that faces increasingly frequent and devastating droughts as the global climate emergency progresses (Solway Reference Solway1994). At the latest count, nearly 20 per cent of Botswana’s population still live in poverty, although the rate is significantly higher – nearly 50 per cent – in a number of remote districts, and poverty disproportionately affects Botswana’s indigenous peoples, the San (World Bank 2015).Footnote 3

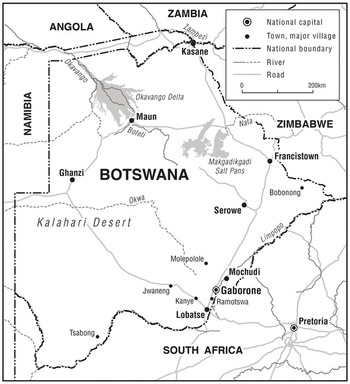

The major thoroughfares of Botswana, built on the proceeds of the diamond trade, trace a rough diamond between larger settlements scattered sparsely around the edge of the country, avoiding for the most part the driest expanses of the Kgalagadi (Kalahari) desert at its heart (Figure 1). The building of roads and opening up of trade routes were key to the wide distribution of the state’s resources and services (Livingston Reference Livingston2019) but also stimulated what seemed, on the face of it, to be a major urbanisation of the country. Gaborone, Botswana’s capital, was one of the fastest growing cities in Africa when I first arrived there in 2003 (Cavric et al. Reference Cavric, Mosha, Keiner, Keiner, Zegras, Schmid and Salmerón2004). And yet, at month ends and on major holidays, the city would become a ghost town. ‘No one is from Gaborone,’ friends and colleagues would commonly remark. The capital city had the best opportunities for work, and people might live and even raise families there, but their home villages were the places to which they returned, in which they had rights to free residential plots where they could build, near which their livestock and farms were kept, and in which they made the bulk of their investments and plans for the future. While census statistics show a trend towards urbanisation in Botswana (see table 1.6 in Republic of Botswana 2015) – much as they do elsewhere in Africa – and while cities, towns, and even ‘urban villages’ have grown rapidly, the numbers belie the mobility and multiplicity of residence that most Batswana take for granted, as well as the ways in which both change over the life course. Both urbanisation and mobility, of course, have figured heavily in mainstream public health explanations for the spread of AIDS, in Botswana and elsewhere (e.g. UNAIDS 2001) – although, as I will suggest in this book, contemporary Tswana patterns of residence and movement may echo historical ones in absorbing crisis, as much as producing it.

Figure 1 Map of Botswana.

My work with the Department of Social Services took me to all corners of the country, including many of the villages my urban-dwelling contemporaries called home, and to some of Botswana’s most remote locations. Far from the main highways, Botswana’s yawning income gap was most evident; so, too, was the government’s role in providing for virtually all of a community’s needs, from health and education to water, housing, and food. Notwithstanding the government’s long-established political agenda of asserting and promoting a unified ‘Tswana’ nation (Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen2012), my travels around the country also made clear the significant diversity of the merafe of Botswana – eight major tribes are recognised, although there are many smaller polities as well (Nyati-Ramahobo Reference Moffat2009) – in everything from language to housing and historical links with groups now separated by national borders. The intersections between these downplayed tribal differences and the country’s inequalities were palpable (on the racialised politics of citizenship, see Durham Reference Durham and Werbner2002b; Motzafi-Haller Reference Motzafi-Haller2002). The stories that follow are tied most closely to the situation in one part of the country, the south-east, and to one morafe – the Balete – but are bound in many ways with these wider realities, and they draw on the insights I took from these diverse, unequal contexts.

Kinship, Selves, and Dikgang

‘You know, it’s funny,’ my mother mused, her voice thin and distant over the phone. I had been pacing aimlessly up and down behind the house in the dark, trying – and mostly failing – to make sense of the confusions of fieldwork for her. She cut straight to the chase: ‘You went there to study care, but it’s like all you ever talk about is conflict.’ I stopped pacing, dumbstruck. ‘Hello? Can you still hear me?’ she called down the line.

My mother’s observation was an expression of concern, but was nonetheless an entirely apt summary of my experience of family life in Botswana. And it gave me a sudden and unexpected way of radically reframing what was going on around me, as something not just frequent but usual, a crucial practice of Tswana kinship in its own right. This book is a response to her observation and an exploration of the extent to which we might understand Tswana kinship in terms of conflict and crisis – which I have glossed as dikgang.

Tswana kinship posed an anomalous case for Southern Africa, and for the descent-based models of kinship that dominated early anthropological work there, from the outset. Drawing on Schapera’s work, A. R. Radcliffe-Brown concluded that the Tswana were ‘decidedly exceptional in Africa’ (Reference Radcliffe-Brown, Forde and Radcliffe-Brown1950: 69). Inheritance and succession to office seemed to fit a patrilineal model of descent, and village wards were roughly patrilocal. But Batswana were endogamous; marriage between parallel cousins – that is, within a given patriline – was permitted, even desirable (although sibling terms were used for these relationships; see Schapera Reference Schapera1940: 41–3; Reference Schapera, Forde and Radcliffe-Brown1950: 151–2). Over time, the preference ‘produced a field of contradictory and ambiguous ties’ that may be ‘at once agnatic, matrilateral, and affinal’ (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1991: 138, emphasis in original). Patrilateral relationships – expected to be fraught with competition and rivalry – were thereby conflated with matrilateral relationships, supposed to be characterised by affection and support. Lineages became tangled and ambiguous, and relationships could be entirely realigned through marriage (Kuper Reference Kuper1975) – a process that was itself highly indeterminate, changeable, and even reversible (Comaroff and Roberts Reference Comaroff and Roberts1977). John and Jean Comaroff have extended this argument to suggest that, rather than structural relationships determining status and behaviour, it worked the other way around: status and behaviour determined one’s relationships. Families or individuals with whom one was on a more equal footing and with whom one was in competition were therefore patrilateral kin; those on a more unequal and non-competitive footing were therefore matrilateral kin, in a highly pragmatic – and implicitly flexible – ‘cultural tautology’ (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1991: 140). I suggest that it is these profound ambiguities – emerging not from structural contradictions (cf. Gluckman Reference Gluckman1956; Turner Reference Turner1957) but from the interchangeability and fluid multiplicity of kin relationships – that make Tswana kinship so fraught and highly contested, and therefore subject to dikgang.

The pragmatic, tautological dimension of Tswana kinship also points to the crucial importance of personhood in producing it and to a unique understanding of what personhood might mean and how it is achieved in this context. In his ruminations on consciousness, mind, and self-identity among Batswana, Hoyt Alverson (Reference Alverson1978) describes Tswana personhood in terms of go itirela – ‘doing-for-oneself’ (ibid.: 133), working or making (for) oneself (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1991: 141) – a framing that emphasises the processes and practices of making persons rather than personhood as a category of thought or being (see also Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1991; Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2001; Durham Reference Durham1995; Reference Durham2002a; Klaits Reference Klaits2010; Livingston Reference Livingston2005; Reference Livingston2008; contrast Carrithers et al. Reference Carrithers, Collins and Lukes1985). Tracing the linguistic root of itirela, Comaroff and Comaroff (Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1991: 140–4) gloss these practices as tiro or work – not in terms of alienable labour, but as a creative process of building up the self by ‘producing people, relations, and things’ (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1991: 143; see also Durham Reference Durham, Cole and Durham2007: 117).

Tiro, according to this model, could involve everything from the acquisition and care of cattle, houses, agricultural land, or material goods to negotiating marriage and the daily work of sustaining it, and to providing care for others. Its central purpose was the establishment of a wide range of social relations. Go itirela – which I have glossed as ‘making-for-oneself’ or occasionally as ‘self-making’, and by which I mean making the self as a social personFootnote 4 – draws together these processes of personhood, which I explore in this book. It emphasises building and accumulation, it is preoccupied with work and with care, and it takes in the material, relational, and moral dimensions of that accumulation and work as well.Footnote 5 Go itirela describes personhood in terms of becoming rather than being, through specific sorts of everyday practice rather than fixed terms of status or office, as practices that are for the self but also extend the self through a wide series of interdependencies (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2001; cf. Fortes Reference Fortes and Dieterlen1973). At the same time, its perpetually processual nature means making-for-oneself is prone to attack, blockage, and even reversal, whether by misfortune or witchcraft; as a result, Batswana must conceal, ‘fragment and refract the self’ in defence (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2001: 275–6; see also Durham Reference Durham2002a; Klaits Reference Klaits2010; Livingston Reference Livingston2005; compare Strathern Reference Strathern1988; Wagner Reference Wagner, Godelier and Strathern1991). In other words, the practice of making-for-oneself echoes the multiplicity, fluidity, and indeterminacy of Tswana kinship; and, like kinship, I argue that it is inherently characterised by risk and potential crisis, or dikgang. To make-for-oneself requires the acquisition and successful negotiation or management of dikgang; it is a moral process as well as a social one, involving the accumulation of skill and experience in mediating the crises to which relationships are prone. In this book, I explore the ways in which kinship is both produced in and constrained by making-for-oneself, and the ways in which the imperative go itirela both relies on and disrupts kinship. The fact that the making of families and of selves is simultaneously complementary and oppositional generates dikgang, and dikgang are a key means of navigating and negotiating those tensions and interdependencies. Taking kinship and self-making together, in their tense interdependency, offers critical means of understanding the generativity of dikgang.

Dikgang: Conflict, Ethics, and the Domestication of History

‘Dikgang’ is a far-reaching and ambiguous term in Setswana. It covers a full range of interpersonal and situational conflicts and problems, but it also means simply ‘news’: the government daily newspaper is called Dikgang tsa Gompieno, the Daily News. In this sense, dikgang can be mundane or calamitous, incidental or imperative; they are volatile and unclear, require interpretation and provoke debate. The dikgang I describe in this book range from minor misunderstandings to heated arguments over neglected responsibilities, to grudges and jealousies; from transgressions of accepted norms to negotiating fines or, to managing the risks of bewitchment. They stretch from problems foreseen in the future to those left hanging from the past. They are frequently events, sometimes acts, but also situations and processes; they are moments of crisis, with lengthy histories and ongoing legacies of attempted resolution that make them chronic. Like puo – which means ‘discussion’ or ‘conversation’ but connotes conflict and discord – dikgang are normal, everyday interactions with an inherent potential to spill into something more dangerous. They are prolific and self-reproducing; inevitably, engaging dikgang risks bringing further dikgang into being.

But ‘dikgang’ is not, of course, an undifferentiated category of trouble. Batswana use several terms to distinguish among dikgang, and, as we will see, several more distinctions emerge in the ways dikgang are assessed and addressed. Dikgotlhang, for example, are outright interpersonal conflicts; dikwetlo are situational challenges that may be shared and faced together by certain people but are not problems between them. A molato is the transgression of a rule or a law; sometimes translated into English as a ‘crime’, it takes in a range of culturally inappropriate behaviour, including acts that could be redressed in the kgotla (although it can also be used informally, like mathata or bothata, for problems). Go seeba batho, to whisper about others or gossip, is a kgang that can create misunderstandings and bad feeling; go gana, to refuse, is a mark of wilfulness and potentially of disrespect that can also undermine relationships. Lefufa, or jealousy, and sotlega, or scorn, are sentiments and behaviours often traced as sources of the problems above – and, worse, of boloi, or witchcraft, and of illness (see Klaits Reference Klaits2010: 4–7 for a detailed analysis). Any of these issues might beset or implicate intergenerational relationships, siblingships, and intimate and conjugal relationships, as well as marking threats that men and women pose to each other and that the home poses to the polity (and vice versa). All threaten unpredictable repercussions for self-making. They also beset relationships between friends, neighbours, workmates, churchmates, and others.Footnote 6 I will argue, however, that the sorts of dikgang that arise, the risks they pose, and the ways in which they are interpreted and negotiated differentiate kin from non-kin, and are a key way in which the spheres of the family and the community are both connected and distinguished.

Potential responses to dikgang are as varied as dikgang themselves. They range from formal negotiations to stillness and personal reflection, from recuperative acts of care to gossip, and even to direct, sometimes explosive confrontations. They may be embodied, materialised, or ritualised; they often cast into the past for insights and lessons and anticipate problems that may emerge in the future. Like news, dikgang are circulated and take different narrative forms in different contexts, which both express and shape relationships over time (compare Werbner Reference Werbner1991 on ‘quarrel stories’ among the Kalanaga, to which we will return). Perhaps the most common responses involve consultation – which itself may range from informal discussion and advice seeking among the members of a household or beyond to formal, mediated discussions for which advisers are called. Who responds, and how, to any given kgang matters: it expresses, structures, and modulates power, and gendered and generational hierarchies in particular. As we will see in the chapters that follow, men and women of different ages may have different responses available to them depending on their generational position, marital status, and personal predilections, skills, and experience. Those able to offer incisive interpretations, to successfully mobilise others, or to mediate relationships in discreet, even-handed ways accrue respect and deference – important means of self-making.

While these undertakings are often the purview of senior men – especially fathers and mothers’ brothers – senior women also bear similar responsibility to and power over their juniors; with some dikgang, younger men and women, too, may exercise their discretion on their own. Dikgang, in other words, are a key means of producing and reproducing the gerontocratic patriarchy that structures Tswana sociality (Wylie Reference Wylie1991), if also perhaps a key means by which it has been unsettled over time. In intransigent, worst-case scenarios, dikgang may be escalated to institutions for response – primarily the kgotla or customary court, but also the police, social work office, or common-law courts. While such escalations may provide a final resolution, they tend to be avoided where possible, in part because they close off the generative possibilities of dikgang, the relationships and self-making projects implicated in them, and the power accrued through them.

Dikgang may be described loosely in these terms, but they resist simplification into discrete categories of conflict. Many dikgang involve combinations of the above characteristics and responses, which may change over time. Situational struggles shared by people and on which they can advise each other, for example, may create interpersonal conflict between them that requires mediation. Something that begins as a kgang between siblings may, in a process of negotiation, be reframed as an intergenerational kgang, or vice versa, thereby exploiting the generational fluidity of Tswana families to address it (to which we return in Part II). A kgang between spouses may also be read as a conflict among siblings or between generations, absorbing conjugal kin relationships into natal ones (Part III), and in turn shifting the appropriate response from one that involves two families to one that requires only the intervention of the husband’s kin. It is not always immediately evident what sort of problems dikgang are when they arise, who they might involve, what might be at stake, or how they ought to be addressed; there is no hard and fast rule as to which response is best suited to which problem. These are all questions that require sustained reflection and interpretation over time.

It is in this sense that dikgang are, above all, ethical undertakings. As Richard Werbner notes, glossing James Laidlaw (Reference Laidlaw2014) and Webb Keane (Reference Keane2014), ‘[ethical] reflection almost always has to be understood in the light of engagement with ambivalence, conflict, and contradiction’ (Werbner Reference Werbner2016: 82). If, as I have suggested, kinship is a series of paradoxes, it stands to reason that misunderstandings that trigger moral reflection and enable a ‘thinking again about paradoxes and contradictions’ (ibid.), drawing out hidden tensions and helping strike the balances required to navigate them, would be defining features of kinship. Dikgang foreground this process of ethical reflexivity and interpretation, in which those involved are encouraged to reflect on the sources and significance of the issues at hand, and in turn on the quality and history of their relationships: on who has done what for whom, and how, with what effects. The efficacy of the response in solving the issue is somewhat beside the point; much of the work of addressing dikgang ultimately suspends or brackets them as passing symptoms of deeper problems, and they will linger, shape-shift, and produce new dikgang in their turn. What matters more is the collective interpretation of the problem, consensus building around the response, and the right reordering of relationships.

Dikgang are thus perpetual; any given kgang bears specific relationships to the problems of the past and the ways in which they were interpreted, and it will set precedents for the future, although initial interpretations may be resisted and recast. In many ways, the navigation of dikgang connotes the practice of wisdom divination (bongaka jwa Setswana), described by Werbner among the Tswapong as ‘the moral imagination in practice’ (Werbner Reference Werbner2016: 86). But among kin, the moral registers against which these assessments are made are also subject to reflection, contestation, and flux – not least in a context where Christian ethics have become so prominent, particularly in connection to development initiatives (Bornstein Reference Bornstein2005; Klaits Reference Klaits2010; Scherz Reference Scherz2014). It is in this layered and perpetual reflexivity, I suggest, that dikgang prove generative: they continuously forge, recalibrate, and sustain a shared, collective ethics.

Batswana do not generally court dikgang. Instead, they tend to avoid conflict explicitly, frequently commenting ‘Ga ke rate dikgang’ or ‘Ga ke rate puo’ (I don’t like conflict/discussion). This reflexive position towards dikgang as a dangerous and undesirable undertaking is an ethically righteous one, intended to contain and ameliorate the risks of conflict. As an ethical field in which ‘sentiment and mutuality are enacted, disputed and struggled with’ (Durham and Klaits Reference Durham and Klaits2002: 780), dikgang pose special risks in certain contexts – including funerals, of which Durham and Klaits were writing – where imperatives of civility, manners (maitseo), and peace (kagiso) are necessary to ‘prevent differences or enmities’ (ibid.: 779; see also Durham Reference Durham2002a). And these risks are perhaps most prominent among kin, whose intimacy and dense interconnectedness make them especially dangerous to one another (see Lambek and Solway Reference Lambek and Solway2001 on dikgaba, illnesses brought upon children by ancestors angered over familial disputes). I suggest that this pronounced risk emanates from the fact that dikgang trace the deep, discomfiting links between the key intersubjective sentiments of love and care, jealousy and scorn (Klaits Reference Klaits2010: 4–7), the threatening ease with which one can slip into or produce the other, and the imperative of managing their meanings and distinctions. Handled well, dikgang involving scorn or jealousy may create and sustain love or care. But in their irresolution, dikgang frequently have more ambivalent, unpredictable effects. As processes that may falter, fail, and later recover, dikgang may generate care and scorn, love and jealousy, reproducing the problematic indeterminacies they set out to tackle. Understood thus, dikgang make it uncomfortably apparent that scorn and jealousy may be just as intrinsic to kinship as care and love – one reason, perhaps, why the risk kin pose to one another is so much greater and more dangerous than that posed through any other relationship.

Dikgang are not ahistorical features of Tswana social life, of course. The specific sites, subjects, and terms of dikgang intersect with and reflect political-economic trends and have mapped broader socio-political change – to which the rich ethnographic record of Tswana disputes since the colonial era bears ample witness. Indeed, it is in dikgang – particularly the dikgang of kin – that the effects of these changes are most often described. From the disintegrating forces of labour migration (Schapera Reference Schapera1940: 352–3) to growing inequality and the sharp rise in woman-headed households with absentee fathers (Townsend Reference Townsend1997: 405–6), to the mortality rates of AIDS and the spectre of child-headed households (e.g. Wolf Reference Wolf, H. and U.2010), the socio-political flux of Southern Africa for over a century has been charted through the changing crises of the family. In her description of how elder women sustain dependencies, Julie Livingston (Reference Livingston, Cole and Durham2007b) supplies a concise historical overview of how these changes have expressed themselves in major intergenerational patterns of dispute:

fathers and sons had struggled since precolonial times for control over cattle, political status, and labor, and colonial-era wage earning refocused these struggles … Mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law experienced a similar refocusing of long-standing tensions around labor, sexuality, and resources in the colonial era, wrought by male labor migration and wage earning. But strained relations between mothers and daughters are a relatively new phenomenon, born of the unprecedented economic and social autonomy possible for single women in the post-colonial economic boom, and the simultaneous pressures to earn cash and support children.

To these we might add the new conflicts that have arisen with urbanisation and growing inequalities, where ‘close relatives, often siblings and in-laws, who grow up in the same conditions, may end up later in very different environments and economic situations’ (Alber Reference Alber2018: 241, on Benin), as well as many others explored in this book.

And yet many of these accounts of the impact of social change on the family miss the ways in which the family manages that change. Dikgang, I suggest, domesticate these shifting histories and political economies – much as Klaits (Reference Klaits2010: 82–121) describes the domestication of inequality, in terms of both experiencing its effects in domestic and kin relationships, and reflexively identifying, assessing, and ameliorating those effects. Dikgang, in some ways, are the mundane equivalent of what Marshall Sahlins called ‘revelatory crises’ (Reference Sahlins1972: 124, 143; see also Solway Reference Solway1994, on drought as a revelatory crisis in Botswana). They expose structural contradictions and unjust or worsening socio-economic and political conditions, while also concealing them – not, here, by attributing them to the crisis itself, but by attributing them to failures in interpersonal relations, and absorbing them into that sphere.

It is in this process of domesticating history that families seem to run the highest risk of collapse – but also prove most resilient. While ‘the extended family institution has been under assault for at least the past 50 years, if not more’ (Madhavan Reference Madhavan2004: 1452, on South Africa), and while these compounding crises have had a tremendous impact on Tswana family life, that impact is perhaps more ambiguous than straightforwardly destructive (see Ørnulf Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1986: 24 for a similar point regarding labour migration). Rather than seeing ‘HIV as an additional destabilising mechanism to an already fragile system’ (Madhavan Reference Madhavan2004: 1452), I suggest that Tswana kinship’s long acquaintance with upheaval and socio-political crisis points to resilience – and that this resilience has its roots in the management of dikgang. As Alber notes of Benin, when social contexts are in a ‘state of transition … disputes tend to arise not only over concrete cases, but also over the norms on which they are based’ (Alber Reference Alber2018: 134). These conflicts not only ‘indicate a general process of ongoing change’ (ibid.: 146) but provide a means of engaging it directly, navigating it, and recalibrating relationships in response to it. While Batswana themselves have long had misgivings about kin ties and their ability to weather crisis (Klaits Reference Klaits1998), such continuous doubt and questioning is also a crucial aspect of sustaining collaboration (Klaits Reference Klaits2016: 417; see also Dahl Reference Dahl2009b), of navigating dikgang, and of absorbing the socio-political shocks of history.

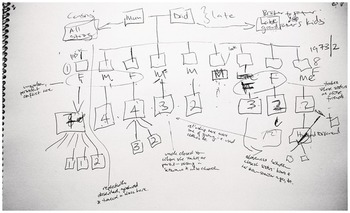

Figure 2 Charting kinship and conflict. A friend and social worker drew this chart while describing her extended family, which quickly became a map of specific conflicts (noted in my hand afterwards).

The dikgang described in this book reflect a particular period of Botswana’s history, which I have glossed as its time of AIDS. But they draw in the histories described above as well – and anticipate possible futures, too. Dikgang do not necessarily map their own historical contexts, but they often recount the process of their navigation over time and the relational histories of those who engage them, using these factors to assess and respond to contemporary crises. If families are ‘caught in the very fine webs of quarrel stories, woven and rewoven in each generation around one misunderstanding after another’ (Werbner Reference Werbner1991: 67), so too are the shifting socio-political sands of history, families’ reactions to them, lessons of success and failure. In this sense, dikgang might be best understood as cumulative, living responses to the experience of crisis across generations, as well as to the crises of particular moments.

Dikgang, Kinship, and Care

By choosing to focus on dikgang, I have sought to question the often subtle but persistent tendency to theorise kinship, as an abstract concept, in ways that echo its idealisation: in terms of harmony, unconditional affection, reciprocity, mutuality, and care. This tendency emanates from projects not unlike my own: those that trace interdependencies between the analytical and social domains of kinship, politics, and religion, while struggling with the question of where and how the limits are drawn in practice; and those that attend to the moral and ethical underpinnings that characterise the lived experience of being kin. The conclusions, however, either lose the specificities of kinship or substitute its moral underpinnings for theory. They also gloss over an ethnographic record – particularly in Africa – that is thick with examples of conflict, inequality, tension, and even violence in family life, rendering these accounts exceptions to the rule rather than constituents of it. I pose conflict and crisis not only as ‘vital element[s] of kinship life’, ‘as inherent to kinship life as intimacy, solidarity and emotional warmth’ (Alber et al. Reference Alber, Alber, Martin and Notermans2013b: 9) but as defining attributes of kinship: of its lived experience, of its gendered and generational relationships, of the ways in which its interconnections with and distinctions from other domains are forged and contested, and of its moral underpinnings put into practice.

The analytical tendency I describe traces its roots to Meyer Fortes (Reference Fortes1969), whose understanding of the imbrications of kinship with politics is a critical antecedent to current ethnographic work on the overlaps and distinctions between these domains, including my own. In identifying the moral criteria of kinship, he proposed an ‘axiom of amity’ based on an ‘ethic of generosity’ that generated a ‘prescriptive altruism’ (Fortes Reference Fortes1969: passim). Kinsfolk, he noted, ‘are expected to be loving, just, and generous to one another’ (Fortes Reference Fortes1969: 237). Of course, in practice, kinsfolk did not always live up to these expectations – or the expectations proved to be so onerous that many would seek to escape them, especially as they saw their lots in life improve. And the same axiom and ethics might also apply to other relations, which were kin-like but also different from kin, from blood brotherhood to neighbourliness. Fortes no doubt succeeded in identifying the guiding principles of kinship among the Ashanti and others, as a matter of ethnographic fact. But as a matter of defining ‘kinship’ analytically, in ways that adequately accounted for its lived experience, his account simultaneously fell short of and overshot the mark: it didn’t quite account for how kin treated each other or experienced their relationships in practice, and it cast the net of kinship around relationships that might not otherwise be considered kin.

David Schneider took these conundrums one step further. Having unsettled latent assumptions that blood or biology formed the universal glue of kinship bonds in his work on American kinship, he identified ‘enduring, diffuse solidarity’ (Schneider Reference Schneider1980: 50) as its crucial code. But, like Fortes, he noted that this moral disposition was not unique to kin. Schneider determined that these were qualities that kinship held in common with nationalism and religion – the ethnographic evidence of interdependencies between domains runs deep – but that nothing else distinguished kinship in itself, that it had ‘no specific properties of its own’ (Sahlins Reference Sahlins2013: 7), leading him to argue for the elimination of kinship as an analytical category altogether. While this somewhat apocalyptic conclusion certainly affected the fortunes of kinship as an area of anthropological research and analysis, it did little to explain away the prevalence and importance of something previously known as kinship in virtually every place studied by anthropologists.

Most recently, Marshall Sahlins has trawled through the vast literature of kinship studies to pose ‘mutuality of being’ (Sahlins Reference Sahlins2013: passim) as the defining, distinguishing, and universal quality of kinship. Mutuality of being fits the intersubjective experience of family and selfhood among the Tswana exceptionally well – and precisely describes the risk that kin pose to one another in many African contexts too, as a vector for witchcraft. But in Sahlins’ explication of mutuality, witchcraft, violence, and other forms of familial volatility and instability mark ‘failures’ of kinship, or even ‘negative kinship’ (ibid.: 59), rather than being constituent elements of it. It is a curious conclusion to draw from an ethnographic record, spanning Africa and Melanesia, in which kinship and witchcraft are not just correlative, but witchcraft inhabits kin relations to the exclusion of other relations (Strong Reference Strong2016) – that is, in which witchcraft proves a unique and defining characteristic of kinship. Likewise, Sahlins excludes the making of hierarchy among kin from ‘what kinship is’ (Reference Sahlins2013: 60) – although, as Robert Brightman points out in response, ‘it is no less intrinsic than sameness’ to the experience of kinship globally (Brightman Reference Brightman2013: 265). ‘Positive’, ‘successful’ kinship remains unremarked.

As Marilyn Strathern notes when looking back over this theoretical history, ‘Mutuality, amity, solidarity: the positive resonances are clear. Unqualified, kinship – like relation – is in English usage a motivated concept’ (Strathern Reference Strathern2014: 5). ‘Kinship’ is a term and concept with histories, connotations, and assumptions of its own. Relations – here, kin relations – are implicitly assumed to be a good thing to have (ibid.: 3), and anything that complicates that understanding is excluded from it. This tendency to sentimentalise kinship as an analytical category (Edwards and Strathern Reference Edwards, Strathern and Carsten2000: 152; see also Stasch Reference Stasch2009: 6) tends to downplay the theoretical relevance of gendered dynamics of power, hierarchy, and control; violence, witchcraft, and abuse; and, as I hope to show here, conflict and crisis. To the extent that it does recognise these latter dynamics, the sentimental tendency tacitly assumes that they are the result of a structural flaw (e.g. Gluckman Reference Gluckman1956; Turner Reference Turner1957) and that kinship should be structured and practised explicitly to avoid or circumvent them (e.g. Stasch Reference Stasch2009: 2). Alternatively, it treats them as a reversal, inversion, ‘dark side’ (Geschiere Reference Geschiere2003), or ‘negative’ aspect of proper kinship, something connected but distinct and opposed.

I suggest that part of the challenge here might be traced to the fact that the anthropology of kinship has tended to focus on figuring out what binds people together, in spite of the hierarchies, conflicts, and fissive pressures that the ethnographic record describes. This focus was explicit in structural-functionalist work on kinship in Africa, which sought the principles of ‘social order’ that might organise so-called stateless societies (and through which they might be governed and reordered by colonial powers); but it has persisted since then, through the expansive frameworks of relatedness (Carsten Reference Carsten2000) and kinning (Howell Reference Hirsch, Wardlow, Smith, Phinney, Parikh and Nathanson2007) as well as Sahlins’ ‘mutuality of being’. It is, however, a preoccupation based on a set of subtle assumptions about personhood: namely, that persons are fundamentally discrete, and that bringing and keeping them together is the central challenge of sociality and relationships. In a context such as Botswana – and, indeed, much of Africa – where personhood is understood as fundamentally intersubjective, the problem of relating is equally one of how to keep people apart – of how to manage and ameliorate that deep interdependency and the risks it presents (a problem Roy Wagner (Reference Wagner1977) described for Papua New Guinea). What these contexts share with others, however, is the rather paradoxical imperative of being together and being apart simultaneously – an imperative that creates tensions. Approaching kinship from the vantage point of these tensions allows us to accommodate diverse modes of personhood, and to establish one possible comparative perspective, without falling back on models that conflate what kinship is with what it should be.

Not only do we see ‘the truth of social relations in events of disruption’ (Stasch Reference Stasch2009: 17) but those disruptions create opportunities and imperatives for ethical reflexivity – that is, for getting at the moral underpinnings of kinship as they are practised, negotiated, contested, and innovated, rather than as ideal forms. The ways in which conflict and crisis are addressed provide crucial opportunities for generating, recalibrating, and sustaining specific social relations – kin relations – in their turn. In other words, conflict and crisis are not simply unfortunate but anomalous things that happen to families; they are continuously produced by and produce kinship, proving to be crucial elements in its resilience. And they include dynamics unique to kinship that define and delimit the family, differentiating it from other social relationships and domains, as well as those that trace its interdependencies. Dikgang are, for better or for worse, what make families family, and not something else.

Perhaps counterintuitively, I suggest that dikgang also provide some unique and complementary perspectives on care, which has formed such a prominent and rich anthropological analytic in understanding Botswana’s response to AIDS (Dahl Reference Dahl2009a; Durham Reference Durham2002a; Klaits Reference Klaits2010; Livingston Reference Livingston2005). In the wake of the widespread government-sponsored provision of antiretroviral treatment (ARVs), dominant public health and interventionist narratives in Botswana refocused on the ‘crisis of care’ AIDS represented for families – picking up on a long-standing trope in which the failures of kinship are often cast. When I first visited Botswana in 2003, the slogan ‘I Care, Do You?’ dominated government public health campaigns, appearing everywhere from flyers distributed at health fairs to roadside billboards countrywide (many of which still remain). In the ‘crisis of care’ narrative, intolerable burdens of care weigh on those looking after the ill and the orphaned, who are often recast as ‘caregivers’ (or batlhokomedi) rather than family members. Government policy targets ‘children in need of care’ (RoB 2005a); NGOs provide ‘supplemental care’ and sometimes call their staff ‘carers’ as well. The discourse has become so pervasive that it is often difficult to talk about family and care in ways that don’t assume both to be objects of concern, requiring intervention (see Dahl Reference Dahl2009b). At the same time, care was neither the defining problematic nor the most striking experience of my time in the Legae household – although, of course, the family expended great energy caring for one another, for their joint property, and for their life projects. Rather, care – like almost every other defining expectation, responsibility, or experience of kinship – was a fraught, open, ethical question, one that produced conflict and crisis; more than that, it was negotiated through conflict and was accessed and even achieved in conflict. It struck me that it might be conflict and crisis, rather than care, that analytically precede the full range of kin-defining dynamics with which this book deals. And this framing provided an apt way of connecting to, but defamiliarising, the ‘crisis of care’ that AIDS is assumed to represent – by presenting the possibility that care is routinely subject to and productive of crisis, if in different ways at different times. I revisit these possibilities in more detail in Part II.

In this sense, care and dikgang are deeply intertwined and unexpectedly generative, each reproducing the other as well as the families they define. To the extent that perceived crises of care motivate a vast range of governmental and non-governmental interventions into the family, they also provide unexpected ways of tracing interdependencies between spheres that anthropologists are accustomed to differentiating as ‘kinship’ and ‘politics’ – a theme to which I turn next.

Intervention

Far from being the basis of the good society, the family, with its narrow privacy and tawdry secrets, is the source of all our discontents.

Five women stood around the boardroom table, leaning their heads together over several scraps of paper spread across its surface. Each bore a word or phrase in block-lettered marker pen. ‘CHILD ABUSE’, said one. Others read ‘HIV/AIDS’, ‘ECONOMIC CRISIS’, ‘JUVENILE DELINQUENCY’, ‘WOMEN’S RIGHTS’, ‘UNEMPLOYMENT’, ‘ORPHANHOOD’, and ‘PASSION KILLINGS’. The women arranged and rearranged the papers in a loose web, placing some together in a line, shifting others across the table. ‘HIV/AIDS’ was particularly peripatetic, moving from the centre of the web out to its margins and travelling right round its edges. Finally, one of the women moved a paper marked ‘FAMILY BREAKDOWN’ to the centre of the web; the others nodded and murmured their approval.

The women were all Batswana and were all professional social workers, the staff of a highly reputable NGO that ran therapeutic wilderness retreats for orphaned children, modelled on the Tswana tradition of initiation. I had met the founder and head of the organisation, Thapelo, several years earlier, while conducting a rapid assessment of NGOs offering services to orphaned and vulnerable children. As it happened, the organisation had been working for years with children from Dithaba – including Lorato and several others I knew from the orphan care project – and so Thapelo and I knew many young people and families in common. In time, we negotiated a formal partnership between the NGO and the Department of Social Services, which involved training government social workers in roughly half the districts across the country to replicate the retreats as part of their orphan care programming. The district in which I lived had been involved in this replication as well; Tumelo, our village social worker, had been among the trainees. Thapelo and her organisation had been thoroughly bound up in my professional, community, and personal life in Botswana for years – an entanglement not uncommon in this sparsely populated and densely interconnected country.

When I returned to Botswana for my fieldwork, Thapelo asked me to assist her organisation in developing a strategic plan. As part of the process, I asked her and her staff to identify what they felt were the major social issues facing Botswana, and to experiment with arranging them in terms of cause and effect, as a ‘problem tree’. Their collective decision to situate family breakdown at the heart of the wide range of issues they had identified resonated with the rhetoric of politicians’ speeches and government policy, the content of campaigns run by agencies such as UNICEF, and the ruminations of village leaders – all of which the social workers weighed up explicitly as they repositioned the scraps on the table. The confusion they faced in terms of where to situate ‘HIV/AIDS’ – as a cause of family breakdown, or an effect, or both – also mirrored that array of discourses. It was a logic and rhetoric in which I, too, had framed my understandings of the epidemic, its effects, and appropriate responses for years; and, like my colleagues, I had come up against the contradictions, frustrations, and dead ends of that logic repeatedly.

The epidemic still fuels popular and professional concern about overburdened systems of care and the purported breakdown of the extended family. Hundreds of local and international NGOs, international agencies, foreign governments, and public and private donors have rushed into this supposed vacuum of care and kinship over the past two decades, with the support and encouragement of the Botswana government. The government itself runs wide-reaching programmes in treatment, home-based care, and orphan care; parallel NGO initiatives in the same areas have mushroomed. During my time at Social Services, I identified over 200 NGOs working with orphaned and vulnerable children alone.

A highly active and influential non-governmental sector is not entirely new to Botswana, nor is an interventionist model of governance. Both have long been bound up with transnational political projects, of colonisation and missionisation specifically, and both have targeted families as critical sites of power and social change. Nor is this project unique to Botswana. Erdmute Alber, Jeannett Martin, and Catrien Notermans describe ‘an irreversible process’, beginning in the colonial era, ‘in which the state, global institutions and non-governmental organisations have increasingly intervened in matters of kinship, family and childhood’ in West Africa (Alber et al. Reference Alber, Alber, Martin and Notermans2013b: 16; see also Stoler Reference Stoler2002 on Indonesia). Jacques Donzelot’s account of eighteenth-century France suggests that interventionism in the family stretches back even further in the colonial imagination: he describes it in terms of ‘policing’, the aim of which ‘is to make everything that composes the state serve to strengthen and increase its power, and likewise serve the public welfare’ (Donzelot Reference Donzelot1979: 7). Alongside public education and psychiatry, he identifies social work and philanthropy as key elements of this project – underscoring the fact that changing modes of intervention are more than technical mechanisms of power, but have long been animated by ethical (and often specifically Christian (Bornstein Reference Bornstein2005; Scherz Reference Scherz2014)) imperatives.

Nonetheless, the advent of AIDS and its logics and rhetorics of familial collapse have motivated government and NGOs alike to pursue a degree of access to the family that is perhaps unprecedented. In the context of successful treatment efforts, perhaps the greatest effects of the epidemic on families lie in these interventions. The fact that they produce such mixed and unpredictable results, are so prone to frustration, and have had such apparently limited influence on the trajectory of Botswana’s epidemic suggests that they have also misread the apparent conundrum of Botswana’s epidemiological situation and continue to be stymied by it. While I do not pretend to offer a conclusive answer to Botswana’s AIDS riddle in this book, I do hope to offer a slightly different means of framing it: as an ‘ordinary’ crisis, with ample precedent – and perhaps overlooked resources of resilience – in Tswana kinship practice and family life.

While the family is a prominent site of intervention for humanitarian and development programmes globally, anthropological analyses of these spheres have generally overlooked it – focusing instead on institutional actors, the production of human universals and futures, and emergent forms of governance (Fassin Reference Fassin2012; Ticktin Reference Ticktin2014). The tendency to avoid families and the micro-processes of relatedness as objects of study suggests an uncanny echo of development and humanitarian organisational practice and discourse itself, in which kin relations have been viewed as encumbrances, threats, and even causes for suspicion (Redfield Reference Redfield2012: 362). And yet the notion of family, like that of humanity, remains ‘meaningful across political, religious, and social divides’ (Ticktin and Feldman Reference Ticktin and Feldman2010: 1) – a key trope in imagining human universality, vested with a variety of shifting, unstable meanings that are nonetheless effectively deployed to a wide range of political ends (Tsing Reference Tsing2005: 8). The humanitarian imperative to provide care for strangers (Redfield Reference Redfield2012; Redfield and Bornstein Reference Redfield, Bornstein, Redfield and Bornstein2011), for example, is underpinned by the conviction that when those who should ordinarily care for people – namely, their families – can’t or won’t, ‘society, either through philanthropy or the state, [is] obliged to stand in’ (Fassin Reference Fassin, Biehl and Petryna2013: 118). In this sense, the principles of humanitarian intervention and government are subtly but deeply informed by expectations, ideologies, and practices of kinship. Like humanitarianism, kinship marks ‘a particularly charged terrain between politics and ethics’ (Redfield and Bornstein Reference Redfield, Bornstein, Redfield and Bornstein2011: 25), drawing together affect and value, rights and obligations, the moral and the political, and bridging the paradoxes they present in similar ways (Fassin Reference Fassin2012: 3). On this reading, the family itself emerges not only as a target but as a sphere of humanitarian governance (see Fassin Reference Fassin2012).

To tease out the connections between family, governments, and NGOs embarking on humanitarian and development projects, I follow the lead of Susan McKinnon and Fenella Cannell (Reference McKinnon, Cannell, McKinnon and Cannell2013; see also Lazar Reference Lazar2018; Yanagisako and Collier Reference Yanagisako, Collier, Collier and Yanagisako1987; Yanagisako and Delaney Reference Yanagisako and Delaney1995), who call attention to the ‘persistent life’ of kinship in the economic, political, and religious projects of ‘modern’ states, corporations, churches, and other agencies. They argue that the social sciences have tended not only to differentiate spheres of analytical concern, or ‘domains’ (kinship, politics, economics, religion), somewhat arbitrarily and artificially, but to assume the natural distinction of those domains in social life, inferring the relative priority of some over others – and rendering the family in particular inconsequential. I attempt to shake off these prejudices by interrogating the extent to which Tswana kinship ideals and practices are discernible in the internal workings of government and NGO offices, or in their interactions with one another, and by asking whether other kinship values may be found in those spaces as well. Finally, I question whether government and NGO programmes that attempt to encompass the family may in fact be generated, permeated, and animated by it.

The notion that Tswana politics might be linked to – and even have its roots in – Tswana kinship practice is not, in itself, new. Nor is the notion that both spheres might be affected by larger global political processes. Schapera (Reference Schapera1970) provided a thorough analysis of the genealogies of the Kgatla chiefs’ kinship affiliations, which he took to be the backbone of village community politics. He drew connections between social roles, kinship terms, and status, and directly linked the supportive closeness of matrilineal relatives, as well as the competitive antagonism among patrilineal relatives, to strategies for accessing power within the chieftainship. And he questioned how the advent of indirect colonial rule might rework these dynamics. In this approach, he aligned himself with the bulk of anthropological literature on kinship in Africa at the time: reading kinship as a stand-in for politics in small-scale societies. By focusing on powerful families, Schapera’s work on the Kgatla chiefs went some distance in establishing the family as a political entity (Schapera Reference Schapera1970) – although it didn’t go so far as to recognise kinship itself as fundamentally political. Here, I seek to broaden and invert his project, by exploring the extent to which organisations we understand to be political entities – government, NGO, or transnational agencies – work in familial ways.

In drawing together the realms of kinship and the political, I do not seek to return to understandings of African societies as ‘small-scale’ or ‘pre-modern’; nor do I aspire to the corollary notions of African politics as fundamentally kin-based. Rather, I suggest that we might reconceptualise all political institutions and work – including those we are accustomed to exceptionalising as ‘Western’ and ‘modern’ – as being fundamentally informed and animated by kinship ideals and practices, and in constant negotiation with both. The practice of politics and governance does not simply arise out of kin practice (Schapera Reference Schapera1940), but neither does it simply act on families (Kuper Reference Kuper1975). It does both, describing a deep interdependency between the state and home, kinship and politics; and this interdependency has taken on transnational implications, brought into sharp relief in the era of AIDS intervention.

The Time of HIV and AIDS

For they had lived together long enough to know that love was always love, anytime and anyplace, but it was more solid the closer it came to death.

This is not a book about AIDS. But it is not a book that eludes or ignores AIDS either. And, in this sense, I hope it will resonate with daily life in Botswana, which was also not about AIDS but was lived in the epidemic’s omnipresence.

Botswana’s first case of AIDS was reported in 1985. By the early 1990s, the spread of the disease had reached epidemic proportions (UNAIDS 2020). In its first stages, AIDS was often framed as a threat to the survival of the nation, in terms of both reversing its developmental gains and facing its citizenry with extinction (e.g. LaGuardia Reference LaGuardia2000; RoB 2005b: 2). The fear of devastation was not altogether unfounded: shortly after I first arrived, in 2004, infection rates were estimated at 37.9 per cent among adults, and in a country of 1.6 million people, 33,000 people are thought to have died of AIDS in that year alone (UNAIDS et al. 2004). In the same year, the number of orphaned children grew so high that a national ‘orphan crisis’ was declared (ibid.).