Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

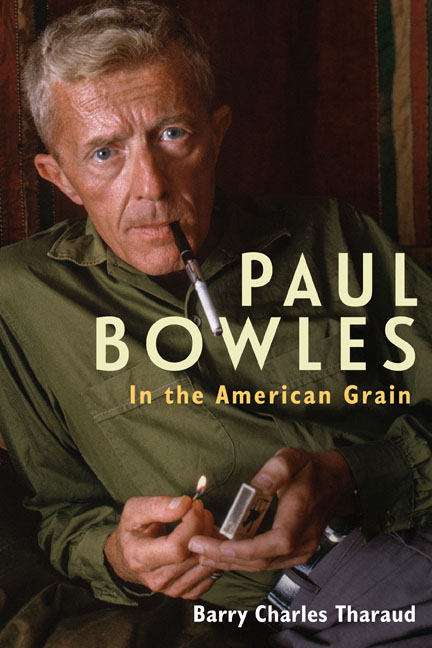

- Introduction: Paul Bowles as a Canonical Writer

- 1 Paul Bowles on Intercultural Understanding: Too Far from Home

- 2 The Discovery of Existence: Without Stopping

- 3 Emersonian Shadows

- 4 Culture and Existence in Bowles’ Short Fiction

- 5 Gide and Bowles in North Africa: The Sheltering Sky

- 6 Language, Noise, Silence: Self and Society in Let It Come Down

- 7 The Spider’s House: The Social Construction of Reality

- 8 Existence and Imagination: Up Above the World

- 9 The Letters: In Touch

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

8 - Existence and Imagination: Up Above the World

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: Paul Bowles as a Canonical Writer

- 1 Paul Bowles on Intercultural Understanding: Too Far from Home

- 2 The Discovery of Existence: Without Stopping

- 3 Emersonian Shadows

- 4 Culture and Existence in Bowles’ Short Fiction

- 5 Gide and Bowles in North Africa: The Sheltering Sky

- 6 Language, Noise, Silence: Self and Society in Let It Come Down

- 7 The Spider’s House: The Social Construction of Reality

- 8 Existence and Imagination: Up Above the World

- 9 The Letters: In Touch

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

IN FEBRUARY 1966, Paul Bowles responded by letter to a prepublication review of his shortest and final novel, Up Above the World, which was published by Simon & Schuster in the middle of the following month. As previously noted in passing (introduction, above), Bowles’ comment to the reviewer was that “A sentence from Borges should have been included in the front of the book, ‘Each moment as it is being lived exists, but not the imaginary total’” (PB1, 1058, notes).

The omitted epigraph indirectly suggests that, apart from individual “moments,” our existence is a fiction, so that insofar as we conceive of the “imaginary total,” we are conscious or unconscious artists of our own lives. For many people, the construction of an “imaginary total” is furnished by the social constructions of one's society—the news, the history, the urban legends, and so forth. Perhaps the most powerful social constructions of the American experience were the New England Puritan traditions that Emerson helped to transform into a secular gospel and that for more than a century widely influenced the “imaginary total” of what it meant to be an American. In contrast to the potentially hopeful implications of Emersonian thought, a consistent theme of Bowles’ fiction is his characters’ inability to use their imaginations to overcome self- and socially-imposed limitations. In the previous chapters of the present work, my approach to Bowles’ fiction is to see it as an analysis of the various obstacles to the kind of creative perception that might lead to greater satisfaction and fulfillment in the lives of his protagonists and, by implication, in our own lives as well. The Emersonian dream of “engineering for America,” as Emerson put it in his speech at Henry David Thoreau's funeral, has in our own time, of course, become bait for the rubes, the naïve, the Boy Scouts. Nevertheless, the diminished view of at least “engineering for a regenerate self” seems to be consistently implied in Bowles’ fiction. Such a moralistic view of Bowles’ work has been obscured by his cult status, as described above in the introduction, but despite occasional sensational elements in a few stories and scenes in his novels, much of Bowles’ work is highly conservative in technique, content, and perspective.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Paul BowlesIn the American Grain, pp. 167 - 182Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2020