Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Figure and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Studying the Everyday

- Part I Constructing Knowledge of the Host Country

- Part II Constructing and Maintaining Boundaries

- 5 The Interveners’ Circle

- 6 A Structure of Inequality

- 7 Daily Work Routines

- Conclusion Transforming Peaceland

- Appendix An Ethnographic Approach

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

7 - Daily Work Routines

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 July 2014

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Figure and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Studying the Everyday

- Part I Constructing Knowledge of the Host Country

- Part II Constructing and Maintaining Boundaries

- 5 The Interveners’ Circle

- 6 A Structure of Inequality

- 7 Daily Work Routines

- Conclusion Transforming Peaceland

- Appendix An Ethnographic Approach

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

It took an interview with a Kenyan expatriate for me to realize that the daily work routines that I had taken for granted as an intervener – routines whose effects I once thought limited to the lives of Peaceland’s inhabitants – in fact directly influenced peacebuilding effectiveness. Following a prevalent line of inquiry in peacebuilding scholarship, I asked this interviewee if he thought that Western or liberal ideas shaped the international efforts in South Sudan, where he was working. He evaded my question and cut to the core of what he, as a former recipient of intervention, found more important:

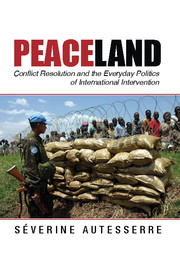

People do not like those camps [in which peacekeepers live]: They are closed, barricaded; [interveners] come out of them all armored. It is not a good system, but it will not change because it is the United Nations’ system. [. . .] Like the security system, you have to constantly listen to a handheld radio, so people appear very divorced from reality. [. . .] When they move, they move in big vehicles – two vehicles, five vehicles – and in every vehicle there is only one person, even though one vehicle could have taken ten people. And [the local people] do not understand [. . .] because there are 30 of them in a bus – some even hanging off the back or on the side of the bus – so they look at [the interveners] and think ‘maybe they are just another kind of human being.’

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- PeacelandConflict Resolution and the Everyday Politics of International Intervention, pp. 216 - 246Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2014