Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Miscellaneous Frontmatter

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- A Word from Parks Professionals, Politicians and Parks Organisations

- Introduction: Dr Hazel Conway (1991)

- 1 Public Parks and Municipal Parks

- 2 The Need for Parks

- 3 Pioneering Parks Development

- 4 The Park Movement

- 5 Design and Designers

- 6 Lodges, Bandstands and the Cultivation of Virtue

- 7 Local Pride and Patriotism

- 8 Planting and Park Maintenance

- 9 Permitted Pastimes

- 10 Recreation Grounds, Parks and the Urban Environment

- 11 Public Parks, 1885–1914

- 12 Later Municipal Park Designers

- 13 Garden Cities and the New Towns Movement

- 14 Sport, Physical Activity and Recreation in Public Parks in the Inter-war Years

- 15 Parks Management – a Changing Perspective

- 16 Decline, Revival and Renewal – the Role of Parks into 21st-century Britain

- Appendix 1 Summary of main legislation promoting early park development

- Appendix 2 Chronology of main municipal and public park developments between 1800 and 1885

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Subscription List

- Index

11 - Public Parks, 1885–1914

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Miscellaneous Frontmatter

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- A Word from Parks Professionals, Politicians and Parks Organisations

- Introduction: Dr Hazel Conway (1991)

- 1 Public Parks and Municipal Parks

- 2 The Need for Parks

- 3 Pioneering Parks Development

- 4 The Park Movement

- 5 Design and Designers

- 6 Lodges, Bandstands and the Cultivation of Virtue

- 7 Local Pride and Patriotism

- 8 Planting and Park Maintenance

- 9 Permitted Pastimes

- 10 Recreation Grounds, Parks and the Urban Environment

- 11 Public Parks, 1885–1914

- 12 Later Municipal Park Designers

- 13 Garden Cities and the New Towns Movement

- 14 Sport, Physical Activity and Recreation in Public Parks in the Inter-war Years

- 15 Parks Management – a Changing Perspective

- 16 Decline, Revival and Renewal – the Role of Parks into 21st-century Britain

- Appendix 1 Summary of main legislation promoting early park development

- Appendix 2 Chronology of main municipal and public park developments between 1800 and 1885

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Subscription List

- Index

Summary

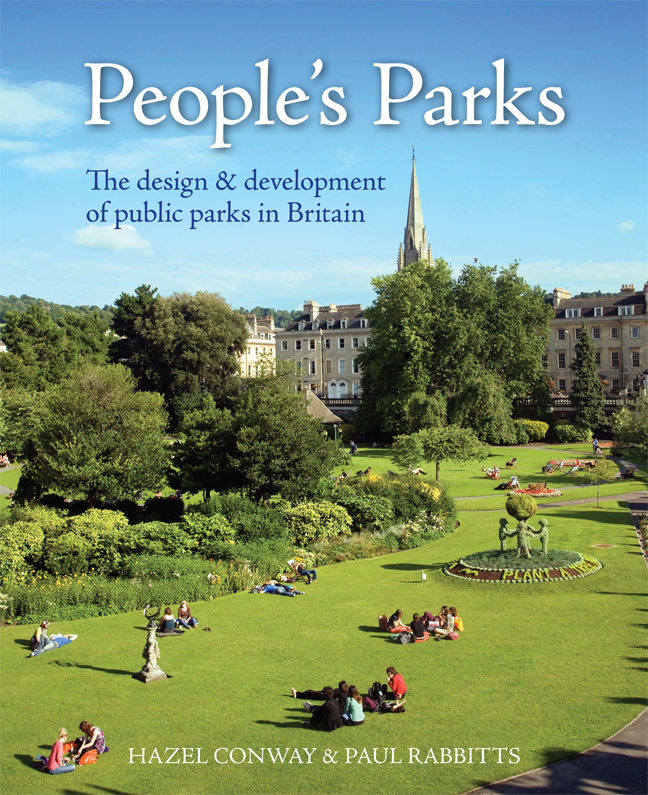

As we have seen, the public park movement began in the 1830s, and sprang primarily out of a desire to improve the health in the overcrowded conditions of the rapidly growing industrial towns. More public parks were opened between 1885 and 1914 than either before or after this period. This chapter, originally written by Harriet Jordan in 1994, looks at the development of the movement during these years.

The need for open space

By the 1880s most towns had been provided with one or more park or recreation ground, often on the town's outskirts or at a short distance from it. The provision of parks within existing built-up areas and in the expanding suburbs arose primarily out of concerns for the health of the population. Parks were seen to be ‘as much of a necessity in town development as a proper drainage scheme’.

Parks were commonly referred to as the ‘lungs’ of the town or city, and it was considered of particular value to increase the number of open spaces, however small, actually within the crowded residential areas of towns. In Middlesbrough, it was at the instigation of the town's first mayor and MP, Henry Bolckow, that an idea of a public park for the residents of the town was first mooted. Dubbed the ‘People's Park’ in its conception, Bolckow was particularly conscious of the need to provide an ostensible ‘green lung’ to ease the plight of the burgeoning industrial population of a town which was granted its charter of incorporation in 1853. Albert Park eventually opened in 1868.

Further amendments to the Open Spaces Act of 1877, in 1881, 1887 and 1890, and amendments to the Disused Burial Grounds Act of 1884, gave the necessary power to the local bodies to carry out such improvements, and many towns adopted a policy of increasing inner-city space. This could prove a costly exercise, but ‘the most expensive plot of land converted into this purpose cannot but be a good speculation, for the health of the toilers in great cities and Large towns is one of the utmost importance’. The perceived benefits of open spaces were not restricted to improving the nation's physical health; they were thought to increase moral health too. The provision of parks in theory made the people happier and therefore better citizens.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- People's ParksThe design & development of public parks in Britain, pp. 181 - 190Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2023