5.1 Introduction

Collaborative climate governance takes place in settings in which various actors join forces to take climate action together. It builds on the existence of multiple and different types of sub-state and non-state actors that form networks and create initiatives to address climate change. As outlined in Chapter 2, in order to fully decarbonize, states need engagement and support from a set of non-state actors. Large-scale decarbonization requires a positive interaction between “policies, publics and politicians” (Reference Jordan, Lorenzoni and TosunJordan et al., 2022), in which sub-state and non-state actors are one part of this dynamic as they can seek to shape how these interactions play out (see Figure 2.1). In other words, collaborative climate governance is dependent on societal actors to respond to the call for action on climate change. While sub-state and non-state actors can engage in their own efforts to reduce GHG emissions or influence states, such efforts will be enhanced if they join together with others in these efforts through cooperative initiatives or networks.

Climate networks are here defined as organized forms of associations that call for climate action. Climate networks that engage various non-state actors such as businesses, municipalities, and civil society actors have grown in significance as a complement to state action on national, regional, and global levels (Reference Lui, Kuramochi and SmitLui et al., 2021; Reference Tosun and SchoenefeldTosun and Schoenefeld, 2017). They are a cornerstone of collaborative climate action as they bring together different non-state actors under one umbrella to pursue common goals. While the potential contributions of such climate networks have been estimated, a lack of data and methodological issues has prevented firm conclusions from being drawn about their actual performance (Reference Hale, Chan and HsuHale et al., 2021). Moreover, few studies have focused on the role of non-state and sub-state climate action domestically to understand how climate networks may contribute to national decarbonization (Reference Roger, Hale and AndonovaRoger et al., 2017). Given the significant potential ascribed to non-state climate action to close the emissions gap (Reference Roelfsema, Harmsen, Olivier, Hof and van VuurenRoelfsema et al., 2018), a pertinent issue for scholars is to study which climate networks gain traction and with what effects.

Sweden’s decarbonization efforts involve engaging a range of non-state and sub-state actors to achieve the overarching goal of achieving net-zero emissions by 2045 (see Chapter 4). Sweden is known for being a corporatist state whereby dialogue with stakeholders is a key feature of policy development (Reference Kronsell, Khan and HildingssonKronsell et al., 2019). This can also be seen in the way the Swedish government has developed its climate governance – with one cornerstone being Fossil Free Sweden (FFS), a multi-stakeholder platform for climate dialogue and action (Reference Nasiritousi and GrimmNasiritousi and Grimm, 2022). However, as outlined in Chapter 2 (see Figure 2.1), state and non-state relations can take different forms and include both cooperation and contestation. For instance, there are a range of other climate networks in Swedish climate governance that are led by non-state actors and are independent of state action. As discussed in previous chapters, these networks are led by businesses, municipalities, and civil society. While this type of “all-hands-on-deck” approach has been described as beneficial and necessary by scholars and policymakers alike in the context of global climate governance (Reference HaleHale, 2016), we know surprisingly little about how these different climate networks, such as the Haga Initiative (a business network) or Klimatkommunerna (a municipal network), contribute to Sweden’s decarbonization process.

The aim of this chapter is to assess the climate networks that involve Swedish actors by examining stakeholder perceptions. It investigates how stakeholders view the effectiveness and contributions of various climate networks through an original survey. The chapter thus takes a different approach to much of the literature by focusing on stakeholders’ perceptions of climate networks. Building on the literature on non-state actors and studies that seek to assess effectiveness, this chapter examines the perceptions of key stakeholders, drawing attention to the tension between the “perceived” effectiveness and the “real” effectiveness of climate action. Perceptions matter because they reveal underlying preferences and motivations and can ultimately affect action (Reference Okereke and StacewiczOkereke and Stacewicz, 2018). Put differently, for collaborative climate governance to work, individuals must see the value in acting collaboratively. Moreover, actors’ beliefs about problems and solutions will shape their perceptions about what works and what does not work and can therefore provide insights into the drivers and dynamics of collaborative climate governance (cf. Reference Tosun and SchoenefeldTosun and Schoenefeld, 2017). Thus, perceptions, while being subjective, provide insights that are difficult to gain in other ways. Through a survey of Swedish actors working on climate issues, this chapter contributes to a broader understanding of the complex web of actors and networks in Swedish climate governance.

Specifically, the chapter outlines a set of multi-actor networks that work to contribute to Sweden’s climate targets and assesses them in terms of their perceived effectiveness. By focusing on different types of non-state climate networks and their relationship to the state, the chapter provides new insights into how different climate networks are perceived as contributing to decarbonization. Examining the perceptions of state and non-state climate networks in terms of effectiveness is not only important for understanding the governance of decarbonization in Sweden, it also provides insights into how agency is generated and with what effects. The questions this chapter addresses include (1) why do organizations join various climate networks; (2) how do the networks contribute to climate action; and (3) which initiative is considered the most effective in contributing to Sweden’s decarbonization? In studying the perceived effectiveness, the chapter contributes to our understanding of why certain networks gain traction and their potential contributions to climate governance.

The chapter proceeds as follows. The next section reviews previous literature on the topic of evaluating the contributions of climate networks. Before highlighting some expectations based on previous literature, Section 5.3 outlines several climate networks in which Swedish actors are engaged. Section four outlines the data and methods, while section five presents the results of the survey. Section six concludes with a discussion of how climate networks are perceived to influence Sweden’s decarbonization and what this implies for collaborative climate governance.

5.2 Evaluating the Contributions of Climate Networks

The importance of climate networks has grown in recent years (Reference Tosun and SchoenefeldTosun and Schoenefeld, 2017). While governance through hierarchy and markets remains important, more innovative forms of governance involving multiple actors have spread at different levels. Non-state and sub-state climate governance has proliferated at national, regional, and global levels (Reference Engström-Stenson and WiderbergEngström-Stenson and Widerberg, 2016; Reference Nasiritousi, Hjerpe and LinnérNasiritousi et al., 2016). However, we know relatively little about the contributions that this type of governance can be expected to make to achieve decarbonization. To some extent, this depends on the state and its relations with sub-state and non-state actors. As was discussed in Chapter 2, states have the legal authority to achieve decarbonization under the Paris Agreement. However, the state relies on other societal actors to make this happen. Climate networks could therefore potentially play an important role in achieving decarbonization on the ground.

However, assessing the effectiveness of climate networks is notoriously difficult (Reference Lui, Kuramochi and SmitLui et al., 2021; Reference Van der Ven, Bernstein and HoffmannVan der Ven et al., 2017). Issues of data availability and establishing causality are part of the challenge but also questions of what constitutes effectiveness when it comes to the work of climate networks. While direct greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions are one type of measure, climate networks can also have other effects that are more difficult to capture (Reference Hale, Chan and HsuHale et al., 2021; Reference Van der Ven, Bernstein and HoffmannVan der Ven et al., 2017). This chapter therefore develops an alternative approach to understanding why certain networks gain traction and with what effects.

The focus of this chapter is on actors that are key to the decarbonization process and that are members or potential members of climate networks. While perceptions of the general public are also important (Reference LindeLinde, 2018), many climate networks involving sub-state and non-state actors may not be well known to the general public. Thus, this chapter focuses on those actors that can directly influence the activities of climate networks through, for example, membership or collaboration. In other words, stakeholders’ perceptions of climate networks matter for attracting participants and collaborators and can therefore ultimately influence the effectiveness of climate networks. In short, “we know that the viability of a collaborative rests on stakeholder perceptions that it is a workable and worthwhile policy approach” (Gash, 2016, p. 462).

This chapter draws on recent studies that show that effectiveness is linked to an initiative’s level of support-worthiness (Reference Bäckstrand, Kuyper and NasiritousiBäckstrand et al., 2021). Climate networks are a form of collective action that can be expected to have greater impact based on strength in numbers (Reference Tosun and SchoenefeldTosun and Schoenefeld, 2017). To be effective, climate networks must attract members or supporters and work with others to implement change. In other words, for an initiative to become effective, it must first generate support from key actors (Reference GashGash, 2016). Support-worthiness depends on a number of factors, and perceptions of the support-worthiness of an initiative differ between groups of stakeholders depending on their interests and norms (Reference Bäckstrand, Kuyper and NasiritousiBäckstrand et al., 2021; Reference Nasiritousi, Verhaegen, Zelli, Bäckstrand, Nasiritousi, Skovgaard and WiderbergNasiritousi and Verhaegen, 2020). In particular, when several actors are working on similar issues, the purpose of a network may be one factor that determines how it is assessed and supported by different stakeholders (Reference HysingHysing, 2022; Reference Nasiritousi and FaberNasiritousi and Faber, 2021). Other important factors are the governance arrangements of networks in terms of participation, transparency, accountability, and effectiveness (Reference Bäckstrand, Kuyper and NasiritousiBäckstrand et al., 2021). Finally, how the work is conducted and communicated are important factors to determining support-worthiness (Reference Nasiritousi, Verhaegen, Zelli, Bäckstrand, Nasiritousi, Skovgaard and WiderbergNasiritousi and Verhaegen, 2020). To gain support, climate networks must become well known among the relevant stakeholders. Thus, to attract participants and collaborators, climate networks must be visible and recognized by a range of actors.

Attracting support is one step toward effectiveness. While actual effectiveness is dependent on the extent to which an initiative solves the problem it was tasked to address, perceptions of effectiveness are subjective and can therefore also differ systematically between stakeholders depending on what they view as being the most important results and achievements (Reference Gutner and ThompsonGutner and Thompson, 2010). While what ultimately matters for decarbonization is its actual environmental effectiveness, studying the perceptions of effectiveness of climate networks among key stakeholders can help us understand some of the contributions that they make beyond direct emission reductions. Thus, while it is notoriously difficult to measure whether climate networks play a significant role in reducing emissions, it is worthwhile to map the perceptions of roles that climate networks may play in contributing to decarbonization.

A focus on the perceptions of stakeholders can provide insights into why certain networks attract more members, what is expected of the networks, and what their impacts are believed to be. This allows for a greater understanding about the paths of influence and wider institutional dynamics of climate networks that other types of measurements may miss. Thus, rather than only focusing on whether climate networks contribute to emission reductions, it is also important to understand the viewpoints of key stakeholders on the wider contributions that climate networks are believed to make in order to assess their broader impacts.

5.3 Swedish Climate Networks

As outlined in Chapter 2, climate networks come in different shapes and sizes and involve different types of relations with the state. While some climate networks engage in collaborative relations with the state, other networks take a more confrontational approach. Through lobbying, implementing, orchestrating, and contesting, climate networks can seek to directly or indirectly influence decarbonization. Because of the multilevel context in which collaborative climate governance takes place (Reference Wurzel, Liefferink, Torney, Wurzel, Liefferink and TorneyWurzel et al., 2020, see also Chapter 3), these relations can look different as actors can pursue climate action on local, national, regional, and international levels individually or jointly with others. The Swedish state has encouraged non-state actors to participate in climate networks by leading and funding a range of cooperative initiatives (Reference Engström-Stenson and WiderbergEngström-Stenson and Widerberg, 2016). There are currently too many climate networks to be covered in one chapter, but what follows seeks to outline examples of different types of networks in which Swedish non-state actors participate, as well as their relationship to the state.

5.3.1 Overview of Climate Networks

For many years, Swedish non-state actors have been involved in transnational climate networks. For example, Swedish municipalities have been involved in several climate networks orchestrated at the EU level, such as Energy Cities and the Covenant of Mayors. Moreover, for many years, the city of Stockholm has been involved in C40, which is a climate network involving some of the largest cities in the world. Similarly, Swedish companies such as AB Volvo and Telia Group have joined the science-based target initiative to set targets in accordance with the Paris Agreement. Sweden is also the home of Fridays for Future (FFF) – a civil society network of youth demanding action in line with the Paris Agreement. More recently, Extinction Rebellion has established its presence in Sweden, with civil disobedience being undertaken to push for climate action. These latter climate networks differ from the former since they do not seek to involve actors to reduce emissions directly. Rather, their activities aim to challenge the state to influence emissions indirectly.

Recent years have also seen a rise in Swedish-based climate networks. Among the business-based networks, the Haga Initiative (Hagainitiativet) and NMC the Swedish Association for Sustainable Business (NMC Nätverket för Hållbart Näringsliv) are two notable examples. The Haga Initiative was established in 2010 with the aim of bringing together companies that take an active role in reducing emissions and influencing policy toward more climate action. It currently has 13 member companies that have pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2030. These companies are large companies with significant emissions.Footnote 1 NMC the Swedish Association for Sustainable Business is a broader network for businesses that work proactively with sustainability issues, with over 200 members. Founded in 1994, this network engages in capacity building and knowledge-sharing in order to advance sustainable businesses. The network also gives out the Sustainable Leadership Award and has recently introduced an award for Sustainability Achievement of the Year.Footnote 2

Similarly to businesses, municipalities also have the potential to join Swedish climate networks. The National Association of Swedish Eco-municipalities (Sveriges Ekokommuner) was established in 1995 with 20 municipalities in Sweden as members. There are currently 98 municipal members and six Swedish regions comprising 45 percent of the Swedish population. This initiative has developed 12 green indicators to help municipalities with sustainable planning and review.Footnote 3 Klimatkommunerna is an association of cities and regions that are working to be frontrunners in the decarbonization process. Initiated in 2001, this network now has 54 members that seek to reduce emissions through the exchange of best practices, collaboration, and influencing national policymaking. The network has developed a 10-point task list to guide municipalities in how to accelerate decarbonization.Footnote 4

A civil society actor, KlimatSverige, is a network that brings together different types of organizations to strengthen climate advocacy through publicizing events and sharing information. By bringing together over 100 organizations, this network undertakes joint campaigns and engages in knowledge-sharing.Footnote 5 In addition to the above-mentioned networks, there are many more networks that focus on public-private collaboration at the local level.

One network that stands out is the state-led FFS, which is also examined in Chapter 4. This is a multi-stakeholder platform established by the government after COP21 in Paris to orchestrate climate action and drive decarbonization in Sweden (Reference Nasiritousi and GrimmNasiritousi and Grimm, 2022). Through dialogue, setting challenges, and establishing roadmaps for fossil-free competitiveness, FFS seeks to coordinate actors to facilitate decarbonization while also strengthening competitiveness. With over 500 actors, including businesses, municipalities, and civil society organizations, FFS is the largest platform to engage non-state actors in climate action in Sweden.Footnote 6

What these networks have in common is that they are seeking to engage different actors in order to accelerate decarbonization. Their relations to the state vary, however, as they have different dynamics and functions. Some networks focus on lobbying, while others focus on implementation or contestation. Through networking, knowledge exchange, sharing of best practices, and influencing other actors, these networks seek to contribute directly and indirectly to reducing GHG emissions.

5.3.2 Expectations

Climate networks come in different shapes and sizes, but what they have in common is that they require engagement by various actors in order to work effectively. Based on previous research, we know that different actors in society have different mandates, interests, and audiences from which they seek legitimacy and will therefore have different reasons for joining a climate network (Reference Nasiritousi and GrimmNasiritousi and Grimm, 2022). Some actors will face pressure to show commitment or feel that there are other benefits of joining a climate network, whereas other actors choose to remain independent and therefore elect not to join a climate network. Previous research has shown that climate networks offer their members some benefits, such as access to financial or political resources (Reference Betsill and BulkeleyBetsill and Bulkeley, 2004; Reference Michaelowa and MichaelowaMichaelowa and Michaelowa, 2017). A question that has been raised in the previous literature is whether climate networks also help members reduce emissions or whether they are just regarded as arenas for discussion or used by actors for the purpose of greenwashing (cf. Reference Berliner and PrakashBerliner and Prakash, 2015). Another question is the effects they may have on other societal actors. While difficult to observe, some studies imply that the effects of interaction between participants in a network can have dynamic consequences beyond the direct actions taken (Reference Cashore, Auld, Bernstein and McDermottCashore et al., 2007). Broader effects may depend on the time scale of cause and effect, meaning that causality is difficult to determine.

Conceptually, we can think of direct and indirect pathways to impact. This chapter argues that climate networks can contribute to decarbonization via four pathways: (1) They can help their members/supporters reduce emissions, for example through peer pressure or new ideas, (2) they can also affect non-members through mechanisms of collaboration or competition, (3) they can influence public opinion through public campaigns, and (4) they can influence political discourse toward climate action through lobbying. Thus, beyond direct emission reductions through members, climate networks also have the potential to effect GHG emission reductions more broadly through leading by example and lobbying. This means that some networks aim to achieve organizational change among both their members and non-members, while other networks focus more on influencing the broader political dynamics. Thus, the extent to which a climate network can be effective in achieving stronger climate action depends both on its members and on how the network works.

Based on the above, we can expect that climate networks draw strength in numbers, to the extent that climate networks that have established recognition among multiple stakeholders and attract support are more likely to be effective (cf. Reference TrumbullTrumbull, 2012). Moreover, the various climate networks have different organizational structures, functions, and membership bases and will therefore differ in the contributions they make toward decarbonization. In terms of the effects on policymaking, Reference MecklingMeckling (2011) finds three factors that can strengthen the influence of different networks: political opportunities (policy crises and norms), coalition resources (funding and legitimacy), and political strategy (mobilizing state allies and multilevel advocacy). In general, it can therefore be expected that a climate network with strong ties to the state can make more significant contributions than a purely non-state initiative, given that political impact is an important pathway for change. This would give an advantage to FFS, both as a state-led multi-stakeholder platform and because it has the support of many types of non-state actors. On the other hand, there is a risk that state-led networks cement business-as-usual approaches rather than driving transformative change (Reference Marquardt and NasiritousiMarquardt and Nasiritousi, 2022; Reference Nasiritousi and GrimmNasiritousi and Grimm, 2022). This leads to the expectation that perceptions of effectiveness depend on the solutions and type of change that actors wish to see (Reference Tosun and SchoenefeldTosun and Schoenefeld, 2017) thereby placing focus on the distinction between transition and transformation discussed in Chapter 2.

By studying the perceptions of key stakeholders, this chapter seeks to understand the contributions of various climate networks to Swedish decarbonization beyond measurable emission reductions. The focus on stakeholder perceptions provides insights into the efficacy beliefs of a range of actors, which, in turn, expands our understanding of how the problems and solutions of decarbonization are viewed by key stakeholders, paving the way for critical reflections about the role of collaborative climate action in broader governance arrangements.

5.4 Methods

The empirical material of this chapter is based on a survey of Swedish societal actors representing a cross-section of organizations, agencies, and businesses. The survey, which was conducted in the spring of 2020, included a set of questions about Sweden’s climate policy and the role of climate networks. The survey did not target a representative sample of the population but used a strategic sampling approach to capture the views of key stakeholders. The survey targeted a total of 1,500 actors across Sweden. These included individuals working at the national, regional, and municipal levels, large and medium-sized businesses, researchers (primarily social science researchers familiar with climate governance research), trade unions, and non-governmental organizations. The aim was to strike a balance between actors with a high profile in climate action (i.e., those actors that publicly highlight climate issues as part of their work) and those actors with a low profile. Invitations to participate in the survey were sent out via email, and the respondents were chosen based on the criteria that they were key stakeholders. For instance, we identified a range of organizations that participate in climate networks and sought to identify similar actors that do not participate in climate networks. Regarding municipal actors, we sent out the survey to two leading politicians in each municipality, as well as to civil servants working with sustainability and/or energy issues in large and medium-sized municipalities.

We received a total of 538 completed online surveys. In terms of type of actor, 25 percent represent businesses (mostly sustainability officers or CEOs); 21 percent are elected officials at national, regional, or local levels; 13 percent work in municipalities (mostly sustainability officers); 11 percent are civil servants at government departments; 11 percent are researchers (mostly social scientists); 7 percent represent business associations; 6 percent represent non-governmental organizations; 2 percent represent trade unions; 2 percent are civil servants at the regional level; and 3 percent work in other sectors. The respondents therefore cover a broad segment of Swedish stakeholders that are, or have the potential to be, important to the process of decarbonization. Most of the respondents (65 percent) work with other issues than questions about climate change. Some of them work for organizations that are members of one or more climate networks, while others have not joined any climate initiative.

The survey questions were jointly developed by researchers from the ACTS project based on a review of climate governance literature that focuses on the effectiveness of non-state action and decarbonization (i.e. Reference Cashore, Auld, Bernstein and McDermottCashore et al., 2007; Reference Michaelowa and MichaelowaMichaelowa and Michaelowa, 2017; Reference Van der Ven, Bernstein and HoffmannVan der Ven et al., 2017). Survey questions that will be assessed in this chapter include several questions about the role of the state, non-state actors, and climate networks in the politics of decarbonization in Sweden. The questions include both closed questions (such as whether and why their organization has joined a climate network) and open-ended questions (such as which climate network they consider to best contribute to Sweden’s decarbonization process and why). The closed questions are reported using descriptive statistics in order to provide an overview of the results. The open-ended questions were inductively coded, whereby categories were created manually when reading through the responses. The responses were translated from Swedish into English by the author.

The data provides insights into the perceptions of key stakeholders on the transformation to a fossil-free society in Sweden and allows for an initial examination of the expectations outlined above. While the results should be interpreted with caution due to the nature of the sample, given that N = 538, the sample nevertheless offers interesting insights into the perceptions of key Swedish stakeholders.

5.5 How Climate Networks Are Perceived to Affect Sweden’s Decarbonization

5.5.1 Main Driving Force of Decarbonization in Sweden

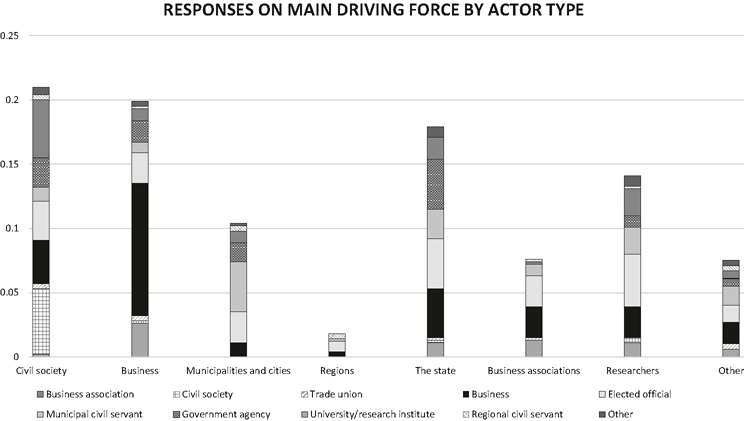

In order to understand the role of climate networks in Sweden’s decarbonization, it is useful to look at the broader context and the perception of key stakeholders regarding which actor is the main driving force behind decarbonization. In particular, it is important to get a sense of who stakeholders regard as being engaged in climate governance in order to gain an insight into the landscape of collaborative climate governance in which climate networks operate. Figure 5.1 shows responses to the question about which actor the respondents view as the main driving force behind decarbonization in Sweden by actor type. Figure 5.1 shows that civil society, business, and the state came out on top. The options that received the least responses related to regions and business associations. In the “Other” category, the respondents identified investors, the EU, individual politicians, and Greta Thunberg as being the main driving forces. Some of the respondents also mentioned that it was not possible to identify a main driver, as there are several driving forces. Overall these responses suggest that the respondents believe that a broad range of actors are the main driving force behind Sweden’s decarbonization, with the key actors being civil society, business, and the state.

Figure 5.1 Responses to the question on which actor is the main driving force behind the decarbonization process in Sweden by actor type

Among these responses, the figure shows a degree of self-selection, whereby civil society chose the civil society category and business chose the business category as the main driving force behind Sweden’s decarbonization. Interestingly, while civil society respondents overwhelmingly chose civil society, business actors were more diverse in their responses. It is also notable that civil society respondents barely highlight the state as the main driving force in Sweden’s decarbonization. This could indicate that civil society actors perceive the state’s climate efforts as weak or ineffective. However, before delving more deeply into perceptions of effectiveness, the analysis will start by understanding the overall perceptions of collaborative climate governance, as well as why organizations choose to join climate networks.

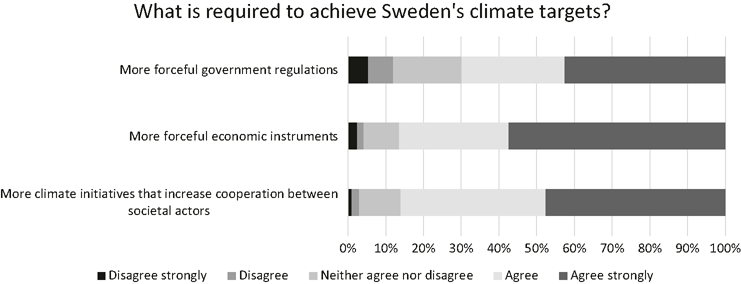

5.5.2 Different Types of Governance Compared

As previously mentioned, there has been an increase in the number of climate networks in recent years in which multiple actors cooperate to engage in climate governance. At the same time, governance through regulation and markets remains a strong features of climate governance. Figure 5.2 shows the responses to what type of governance is required for Sweden to achieve its climate targets. While most of the respondents support all three forms of governance, collaborative governance has the greatest support, while there was more resistance toward government regulations. This means that the hierarchical regulatory state model is recognized as being important, but markets and networks are the preferred governance modes.

Figure 5.2 Responses to the question on what is required to achieve Sweden’s climate targets

5.5.3 Motivations for Joining Climate Networks

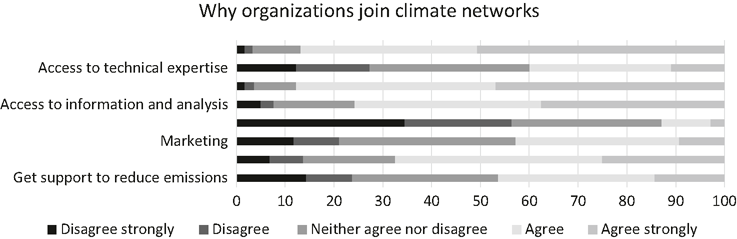

The next set of questions was only posed to respondents who indicated that their organization had joined a climate network. The reasons for joining a climate network could provide insights into what it is expected to deliver on. When asked about why their organization decided to join a climate network, the respondents stated that it was primarily for networking reasons and to show commitment (see Figure 5.3). Joining a climate network in order to gain access to information and analysis was also a frequent response, whereas joining a climate network in order to gain access to financial resources was the most infrequent response. Interestingly, almost 24 percent of the respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that organizations join a climate network in order to gain support to reduce emissions. Overall, the responses indicate that climate networks are viewed as an opportunity to network and show commitment, as well as influence and lobby, more than a means of directly reducing emissions.

Figure 5.3 Responses to the question on why organizations join climate networks

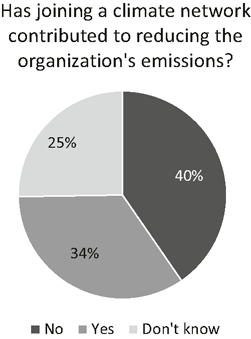

When the respondents were asked whether joining a climate network has contributed to reducing the organization’s emissions compared to before the organization joined the network, more respondents answered no (40 percent), compared to yes (34 percent), whereas 25 percent of respondents stated that they don’t know (see Figure 5.4). This again highlights that reducing direct emissions may not be the main contribution of climate networks.

Figure 5.4 Responses to the question on whether joining a climate network has contributed to reducing the organization’s emissions

5.5.4 Impact of Climate Networks

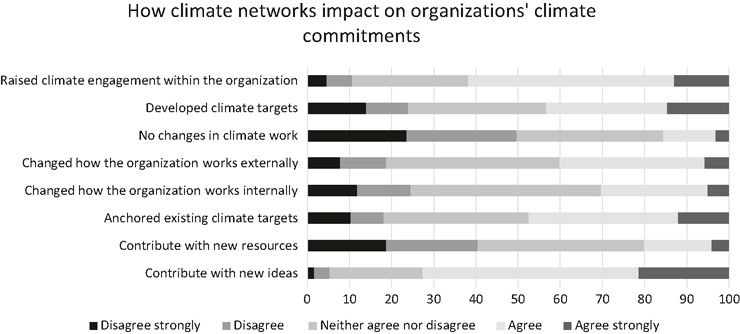

When asked more specifically about how climate networks impact an organization’s climate commitments, most respondents agreed with the statement that they offer new ideas and increase climate engagement in the organization (see Figure 5.5). Many of the respondents disagreed that climate networks have no impact but agreed that climate networks change how the organization works externally to a greater extent than how it works internally.

Figure 5.5 Responses to the question on how climate networks impact on organizations’ climate commitments

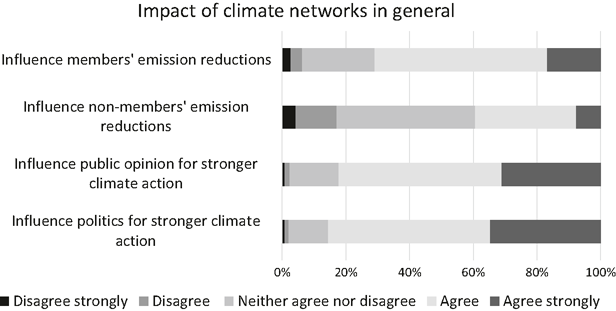

When asked about the impact of climate networks in general, there was strong agreement that climate networks influence politics and public opinion to effect decarbonization efforts (see Figure 5.6). There was less agreement on whether climate networks influence the emission reductions of members and non-members. This highlights the political functions that climate networks serve, which are difficult to measure objectively. The respondents’ perceptions highlight that one of the main roles of climate networks is to push for stronger climate action more broadly. This indicates that the indirect form of impact that is difficult to measure may play a more significant role than the direct form of impact. This finding highlights the need to better understand the broader societal effects of climate networks.

Figure 5.6 Responses to the question on the impact of climate networks in general

5.5.5 Recognition of Climate Networks

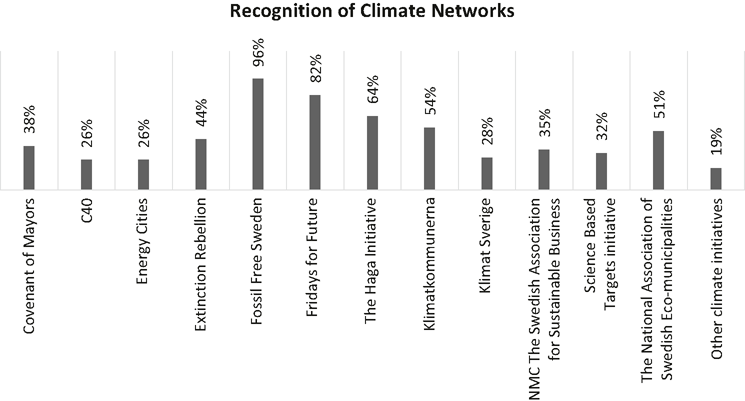

As previously outlined, climate networks that are well known by the stakeholders that they wish to influence are more likely to have an impact. In order to gauge the recognition of key climate networks among Swedish stakeholders, the main climate networks were listed, and all respondents were asked to indicate the climate networks with which they were familiar. Interestingly, FFS was recognized by virtually all respondents. Being a state-led network, this finding might not be surprising, but it shows that FFS has been successful in making itself known to diverse stakeholders. The second most recognized initiative is FFF, and the third the Haga Initiative. As shown in Figure 5.7, Swedish climate networks were more well known compared to transnational networks (with the exception of FFF, which is transnational but was started in Sweden).

Figure 5.7 Responses to the question about the climate networks with which the respondents were familiar

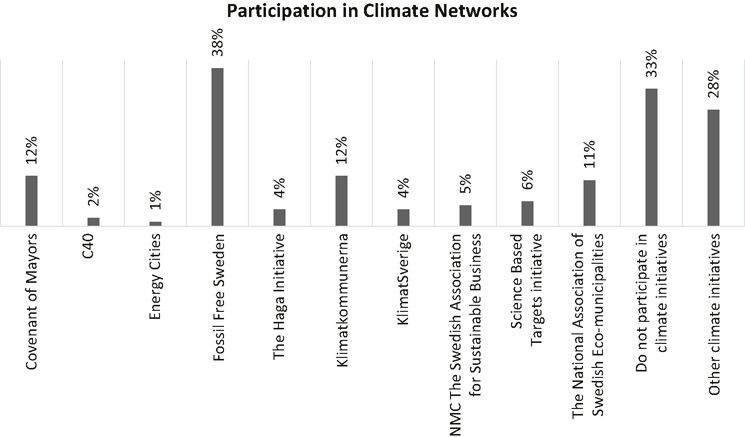

When the respondents were asked about which networks they were members of, 33 percent of respondents stated that they were not members of climate networks (see Figure 5.8). Thirty-eight percent indicated that they are part of FFS, whereas 28 percent mentioned other (often more local) climate networks. The fact that FFS has the most members among the respondents is not surprising since it is open to many different types of actors. The high number of respondents who indicated that they are part of other climate networks indicates the plurality of networks that comprise different constellations of actors.

Figure 5.8 Responses to the question on which climate initiatives the respondents participate in

5.5.6 Perceptions of Effectiveness

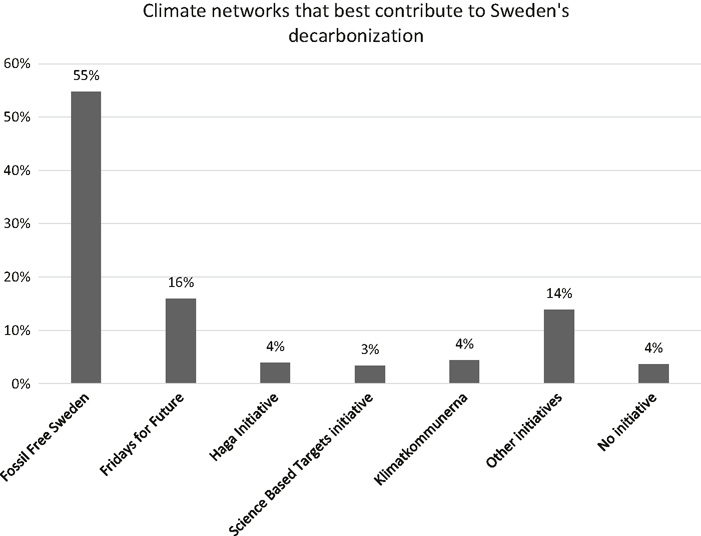

The survey also contained an open-ended question about which climate network the respondents considered made the best contribution to achieving Sweden’s climate goals and why. As Figure 5.9 shows, FFS came out on top again, followed by FFF. However, the reasons given for this differ considerably. The reasons given for the effectiveness of FFS include the multi-stakeholder nature of the forum, the focus on reducing industrial emissions, and the narrative on improving Sweden’s economic competitiveness throughout its work. For FFF, on the other hand, the reasons provided for its effectiveness included its visibility, that it has anchored its message in public engagement, and that it is not supported by any lobby organization.

Figure 5.9 Responses to the question on which climate network best contributes to Sweden’s decarbonization

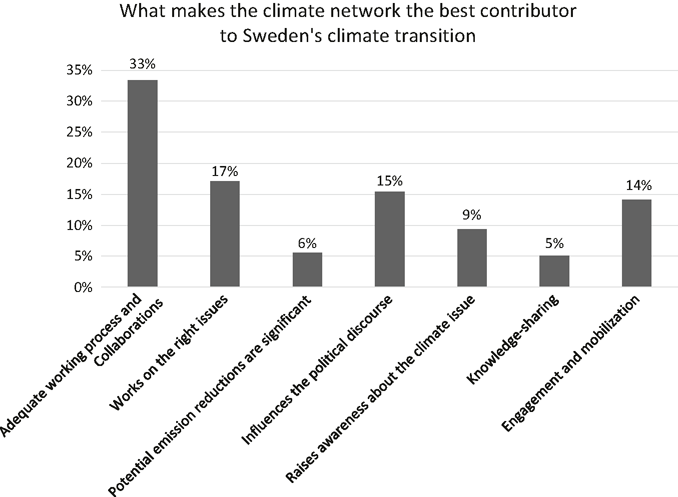

When coding the different responses to the why question, interesting categories of responses emerged, as shown in Figure 5.10. Whereas some respondents placed emphasis on the ways in which the climate networks work, other respondents placed emphasis on their impact, particularly in terms of real or potential impact on emission reductions. Most responses were about how the climate networks work and with which collaborators. Responses in this category included the following: “Fossil Free Sweden, through its overall working methods and collaboration with the business community”; “The Covenant of Mayors, which has a good spread and provides concrete work in municipalities”; “The Haga Initiative, which coordinates and facilitates for private actors and is an example of where you voluntarily do something that is outside the authorities’ orders. The work therefore involves additionality.” These examples highlight that many respondents perceive the effectiveness of climate networks in terms of how they work and with whom. The desire to work with the right actors to drive change is among the most frequent responses.

Figure 5.10 Responses to the question on why a climate network was deemed to best contribute to Sweden’s decarbonization

The second most frequent category was about having an adequate focus/approach, where there are different perceptions of what constitutes the best approach. Examples here include: “Science based target – scalable to all industries and globally”; “Extinction Rebellion. Its demand to speak clearly, act now and strengthen democracy with citizens’ councils is clear and good. Its method, peaceful civil disobedience, has historically proven to be successful. Everything else is going too slowly”; “Fossil Free Sweden works in a constructive spirit, with the climate issue as an opportunity to strengthen Sweden’s competitiveness.”

The third most frequent category was about the climate network influencing the political discourse. Examples include: “Fossil Free Sweden gets companies involved and shows the politicians that they should not be afraid to make climate decisions that concern companies.” “The Haga Initiative offers a proactive and constructive voice to the political debate”; “Fridays for Future. It raises the issue on the political agenda and has created pressure to not ignore it.”

Factors such as creating engagement and mobilization, raising awareness of climate change, focusing on potential emission reductions that could have significant effects, as well as contributing to knowledge-sharing were other frequently mentioned reasons for discussing a particular climate network as best contributing to Sweden’s decarbonization.

Taken together, there are many potential roles that climate networks could play. The respondents’ perceptions of effectiveness appear to depend on their ideas about what needs to change and how. Perceptions of what makes a climate network effective therefore also provide insights into how change is envisaged as part of the decarbonization process. The responses particularly seem to differ depending on whether the respondents believe there is a need for incremental sectoral change or for deeper societal change to achieve the climate targets. For instance, several of the respondents who argue that FFF is most effective highlight that other networks, such as FFS, are too slow and focus a lot on discussing terms set by incumbent businesses. This highlights possible trade-offs in effectiveness whereby short-term effects may lead to more long-term difficulties if current efforts result in slow change when a more disruptive form of transformation toward deep decarbonization is needed. Nevertheless, both the supportive and the critical respondents agree that climate networks are not mere arenas for discussion but that they also impact decarbonization – for better or worse – and that they play a political role that could have broader effects. These findings are in line with previous research that argues for the need to consider the broader societal effects of collaborative climate governance (Reference Van der Ven, Bernstein and HoffmannVan der Ven et al., 2017). Understanding the impact of climate networks beyond mere emission reductions is therefore important, not only from an academic perspective but also from a policy perspective.

5.6 Discussion and Conclusions

Climate networks come in various shapes and sizes and have different roles to play. With the involvement of multiple actors, it can be difficult to discern who is influencing whom and who is governing what. The results presented above indicate that collaborative climate governance is considered important in Sweden’s governance toward a fossil-free society, alongside hierarchy and markets. While direct emission reductions by the members of climate networks do not appear to be their most important contribution, there are indications that climate networks have a major political role to play that may lead to emission reductions if politicians take a more active role in steering toward achieving decarbonization. The analysis highlights the important role of the state in providing purposeful steering toward decarbonization to ensure that mid-term and long-term climate targets are actually achieved. On their own, climate networks will not close the emissions gap as they are unlikely to be the main drivers of deep and rapid decarbonization (Reference Michaelowa and MichaelowaMichaelowa and Michaelowa, 2017). While climate networks are deemed important for engaging multiple actors, emission reductions require political frameworks and adequate incentives for non-state actors to contribute toward decarbonization and achieve committed targets, such as through regulations and financial carrots and sticks (Reference Lui, Kuramochi and SmitLui et al., 2021). Thus, in this sense, a key role of collaborative climate governance could be said to be to allow the state to gain buy-in and support for expanding climate action.

However, this chapter also shows the variations in existing climate networks and the differences in how they are perceived. In particular, the results highlight that perceptions of effectiveness differ between actors and may be linked to the approach preferred toward decarbonization in terms of the kind of transformation that is envisaged. This highlights the “eye of the beholder” issue regarding perceptions of effectiveness (Reference Gutner and ThompsonGutner and Thompson, 2010) but also provides insights into the differences in how actors perceive the coming change in terms of what will change and how. In this regard, the transition versus transformation framing can help us understand why certain actors view one climate network as more effective than another. Also, the role of business was a clear dividing line whereby some respondents highlighted that climate networks must involve business actors in order to be effective, while other respondents cautioned against relying on business interests. Notably, several respondents highlighted that while FFS has been effective in its communication to become familiar among stakeholders, it is not delivering on the required emission reductions and will not do so because it is guided by business interests. This is in line with a previous study on FFS, which shows that managing such collaborative networks can result in a “governance dilemma” for the initiative because it must attract a sufficient number of actors with significant emission reduction potential without locking in business-as-usual work practices (Reference Nasiritousi and GrimmNasiritousi and Grimm, 2022).

Taken together, the analysis highlights the potential and limitations of the model of collaborative climate governance. While analyses that only focus on emission reductions may miss the important effects on other societal actors that may drive change, the role of climate networks in driving decarbonization should also not be exaggerated. Ultimately, many of the changes need to be facilitated by government policy. While climate networks can give a push to some policies, they may also amplify the voices of already strong interests and contribute to state capture. It is therefore important to examine whether the networks are merely an extension of interest by status quo players or whether they aim to generate deeper changes. In other words, the political effects of climate networks are barely understood and deserve more attention in order to understand the role of collaborative climate governance in large-scale decarbonization (Reference Van der Ven, Bernstein and HoffmannVan der Ven et al., 2017).

The emphasis of this chapter on examining stakeholders’ perceptions of effectiveness has provided new insights into how actors view different types of climate networks. While the survey results would suggest that there is a high level of support for collaborative governance in Sweden, there is also support for more confrontational relations with the state. The results show that over a period of a few years, FFS has established itself as a recognized and well-regarded climate network. Being state-led, it has the advantage of providing a bridge between state and non-state actors. The results show that this type of orchestration is perceived to best contribute to Sweden’s decarbonization. Nevertheless, while there is a high level of perception of effectiveness, this would appear to be linked to a focus on a narrow transition rather than transformation as the end state. In particular, there is a risk that this type of initiative will play down the politics to gain traction, with implications for how problems and solutions are addressed (Reference Jernnäs and LövbrandJernnäs and Lövbrand, 2022; Reference Marquardt and NasiritousiMarquardt and Nasiritousi, 2022; Reference Nasiritousi and GrimmNasiritousi and Grimm, 2022). The links between perceptions of effectiveness and actual effectiveness must therefore be further investigated, taking into consideration which end-state actors perceive as being viable and desirable.

The results of the survey demonstrate that a more confrontational approach is perceived as being more fruitful by a large proportion of respondents, particularly those respondents that express the need for deeper changes to current structures. In contrast to FFS, the second most successful climate initiative – FFF – has a different relationship with the state. Stakeholders value the work of FFF as it challenges the state to be more ambitious in its climate policies and raises awareness of the urgency of transformation. It is believed that this type of climate initiative contributes to decarbonization by putting pressure on the state to take action faster. Thus, there is a role to play for different networks that have different relations to the state. This is in line with the literature on organizational ecology, which highlights that there are “niches” that can be occupied by various actors (Reference Abbott, Green and KeohaneAbbott et al., 2016). As large-scale decarbonization requires transitions across systems and sectors, there are opportunities for sub-state and non-state actors to engage with the state in multiple forms through both collaborative and confrontational relations.

The chapter offers new understandings of the role of climate networks in Sweden’s transformation to a fossil-free society. By studying perceptions, the chapter has shown different reasons for joining networks and perceiving them as effective, which provides insights into how key stakeholders view the role of collaborative climate action. Since the analysis has relied on an expert survey and was presented using descriptive statistics, it could be useful for future studies to develop additional methods to study the impacts of climate networks. While studying perceptions can provide important insights into how stakeholders view effectiveness, actual effectiveness would likely be better examined through in-depth studies of particular climate networks. Future research could then use case studies to examine the contributions of particular networks over time and further look at who is involved, on what terms, and with what effects. Moreover, as the political effects through lobbying and other paths of influence were found to be important, future studies could interview politicians in order to triangulate these findings.

In sum, climate networks are important to Sweden’s decarbonization, which relies on a collaborative model. The potential and limitations of this type of governance have several implications for policymakers. For example, policymakers who want to drive change can use climate networks as stepping stones toward a spiral of ambition that can influence key stakeholders. For this to happen, however, policymakers must be prepared to steer more purposefully and create the right incentives for more actors to follow suit. In other words, establishing a collaborative multi-stakeholder platform such as FFS is no substitute for clear climate leadership from the state. In fact, many of the policy proposals developed by FFS demand state action to move things forward (Reference Nasiritousi and GrimmNasiritousi and Grimm, 2022). This implies that hierarchy, markets, and collaborative governance all need to coexist through a complex web of interactions. The types of trade-offs and dilemmas identified in this chapter imply that none of this will be easy. However, the survey responses show that many non-state actors in Sweden are willing to participate in the transformation to a fossil-free society. However, what this transformation will look like is clearly contested by various stakeholders. Thus, the state has an important role to play in arbitrating between different visions of a fossil-free society and in forging a clear direction for decarbonization.