Book contents

- Politics and ‘Politiques’ in Sixteenth-Century France

- Ideas in Context

- Politics and ‘Politiques’ in Sixteenth-Century France

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Note on the Text

- Part I The Politique Problem

- Part II C. 1568–78

- Part III C. 1588–94

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 June 2021

- Politics and ‘Politiques’ in Sixteenth-Century France

- Ideas in Context

- Politics and ‘Politiques’ in Sixteenth-Century France

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Note on the Text

- Part I The Politique Problem

- Part II C. 1568–78

- Part III C. 1588–94

- Conclusion

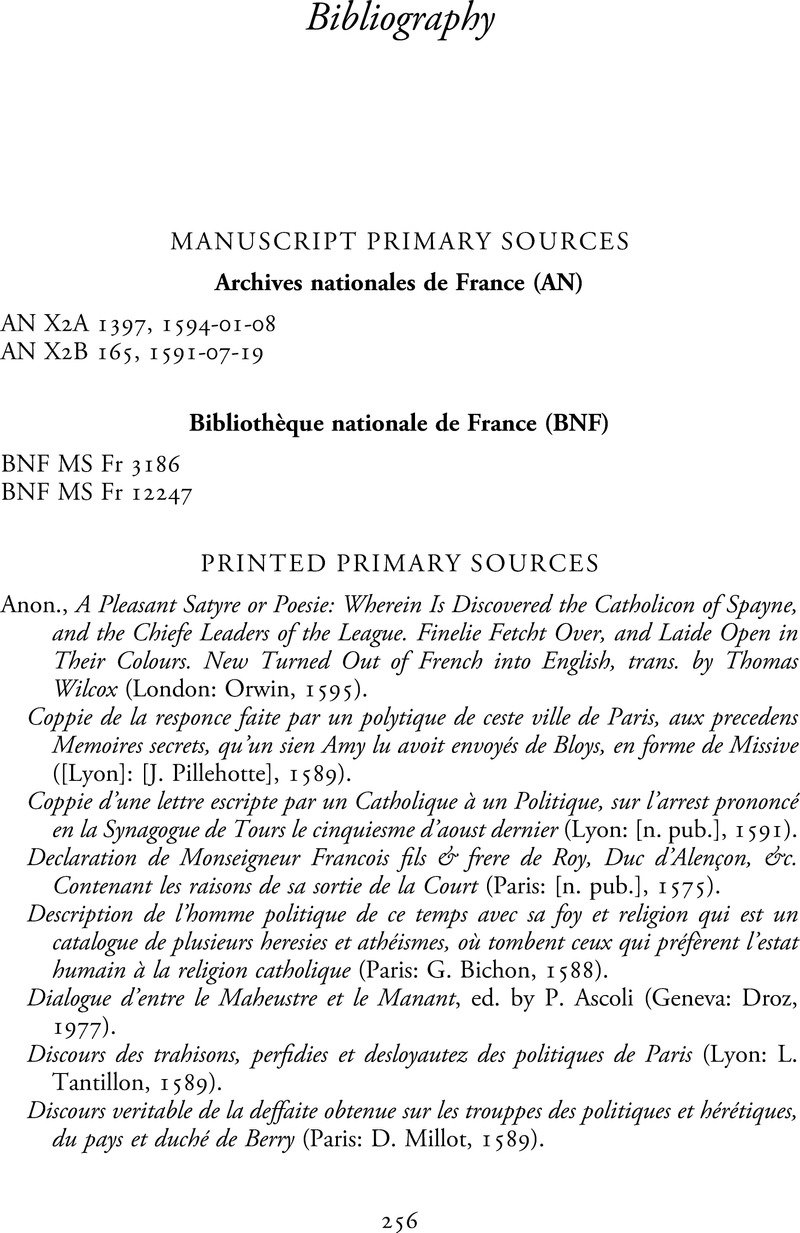

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Politics and ‘Politiques' in Sixteenth-Century FranceA Conceptual History, pp. 256 - 277Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021