This book is concerned primarily with the school reforms of the 1950s to 1970s. However, historical legacies shaped the conditions actors faced during the postwar reform period. This chapter therefore summarizes the evolution of national education systems, meaning “system[s] of formal schooling at least partly funded and supervised by the state” and providing “universal education for all children of school age” in Norway and in Prussia (later North Rhine–Westphalia, NRW) up to the 1950s (Reference GreenGreen, 2013, 297). It sheds light on how political playing fields and cleavages developed, forming the school as an institution. As we shall see, differences in cleavage structures contributed to differences in school policy from an early date. However, there are also similarities: by the 1950s, both school systems consisted of comprehensive primary schools, followed by segmented lower- and upper-secondary schooling. The focus lies on general primary and secondary education, so the development of postsecondary and vocational education is not discussed.

Schooling in Norway up to the 1950s

The Formation of the Norwegian State and Education System

The Christian education of Norwegian children was originally controlled by the Danish-Norwegian church. A national education system developed gradually from the eighteenth century onward. In 1739, the Danish-Norwegian King Kristian VI (1730–46) issued an ordinance to schools in the countryside (allmueskoler) that stipulated that all children between seven and ten to twelve years of age should go to school for at least three months of the year. Throughout the eighteenth and well into the nineteenth century, the only subject taught to the majority of students was Christianity, meaning the memorization of scripture, prayers, and learning to read (Reference TveitTveit, 1991, 95ff). The pietist allmueskole built on the idea that the population in its majority was “lazy and stupid” (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 36). The allmueskole teachers were among the poorest of the population. The allmueskole was forced on the population from above and was meant to teach the common people respect for church and king. However, the reforms did lead to the eradication of illiteracy by around 1800 (Reference TønnessenTønnessen, 2011, 23).

Besides the allmueskole, latinskoler (Latin schools) developed as a school type for the elites. They originally prepared students for church services, but gradually also for civil service. Realskoler or borgerskoler were founded as another type of lower-secondary school with a modern curriculum, inspired in part by the ideas of the Enlightenment (Reference MyhreMyhre, 1971, 27). These schools were driven mainly by representatives of the new class of merchants. They wanted their children to have a different kind of education than the Latin schools could offer. The lower-secondary schools taught not only religion and reading but also arithmetic, history, geography, and drawing. These subjects were also open to girls. Boys received additional education in subjects such as German, English, French, mathematics, bookkeeping, letterwriting, navigation, or declamation. By the early 1800s, these schools had three times as many students as the Latin schools (Reference TønnessenTønnessen, 2011, 21f).

In 1809, mathematics, modern languages, and natural sciences were introduced to the curriculum of all secondary schools. The new regulations made it possible to combine lower-secondary schools and Latin schools so students who did not intend to go to university could receive a secondary education without Latin (Reference MyhreMyhre, 1971, 28f). In this period, Norwegianness was not a topic in the schools. The textbooks were all written in either Danish or German. Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug and Mediås (2003, 52) therefore claim that “Norwegian schools during pietism belonged to a uniform Christian-Latin European culture.” Pietism in education remained hegemonic until around the 1840s (Reference TveitTveit, 1991, 113; Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 54).

After the Napoleonic wars, Denmark was forced to cede Norway to Sweden. This was unpopular among the Norwegian elites. A group of 112 Norwegian civil servants, businessmen, farmers, and a few aristocrats assembled on April 10, 1814, to draft a Norwegian constitution. On May 17, 1814, the constitution was signed. It granted all male farmers, civil servants, and the small urban middle classes voting rights for the Norwegian parliament. Most of the population consisted of poor crofters, farmhands, and the lumpenproletariat (Reference BullBull, 1969, 32ff). After Norway’s independence was declared, Sweden attacked Norway, so that the union with Sweden and the Swedish king eventually had to be accepted by the Norwegian government. While Sweden dominated the foreign politics of the union, Norway was relatively independent in domestic policy. In 1821, all privileges were taken from the small Norwegian aristocracy (Reference BullBull, 1969, 9). In 1833, farmers obtained a near majority in the Norwegian parliament for the first time; from 1836 to 1837, municipal government was democratized.

The School As a Nation-Building Institution

In the years 1848 to 1851, a mass movement of workers, crofters, journeymen, and servants was formed, but this Thraniter movement, named after its leader, Marcus Thrane, was broken up (Reference BullBull, 1960, 26ff). From around 1860, industrialization set in and the middle classes grew. A liberal movement began to develop that opposed the old regime of senior civil servants and the union with Sweden. The movement was named Venstre, literally “the Left,” due to its seating on the left side of parliament. It was kept together mainly by a shared desire for national independence (Reference SejerstedSejersted, 2011, 52). In 1883–4, the Liberal Party (Venstre) was founded and remained dominant in Norwegian politics for many decades. The liberals formed a majority in parliament and came to power in 1884. In the same year, the Conservative Party (Høyre, literally “the Right”) was founded, which represented higher civil servants and the upper ranks of the church. From the 1870s on, unions sprang up in various trades. In 1887, the Norwegian Labor Party (Arbeiderpartiet) was founded, followed by the foundation of the Norwegian Federation of Trade Unions (Landsorganisasjonen) in 1899. In 1903, the population of the northern provinces Finnmark and Troms voted the first four representatives of the Labor Party into parliament (Reference BullBull, 1969, 70).

The ethnic community of the Norwegian people became a major topic. Center-periphery and urban-rural divisions became more pronounced. Important figures, such as the farmer’s son Ivar Aasen, argued that rural Norwegian culture and language represented the true Norwegian soul, while the culture of the cities was Danish by origin, fake and elitist. From the 1840s to the 1870s, Aasen and others developed a written language form based on Norwegian dialects and Old Norwegian; it was called landsmål (later called nynorsk [New Norwegian]). Others, such as Marcus Jacob Monrad and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, thought that culture was of a transnational nature and had come to Norway through the urban elites. Bjørnson suggested naming the Norwegian variety of Danish riksmål (later bokmål [Book Language]) (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 57). In 1885, the Norwegian parliament decided that the new landsmål should be put on a par with riksmål as an official written language in schools and within the state. From 1892, both written forms of Norwegian were allowed as teaching languages in the primary school, and it was stipulated that children should learn to read both. By 1900, around 250 school districts, especially in central, western, and some parts of northern Norway, had introduced landsmål as their main written form used in schools (Reference Haugland, Ramsdal, Vikør, Worren, Almenningen, Roksvold, Sandøy and VikørHaugland et al., 2002, 87f).

During the 1850s and 1860s, an educational reform movement developed. It was influenced by ideas from the Enlightenment tradition and romantic idealism, originating from Germany and Denmark. A more optimistic view of humanity replaced pessimistic notions associated with pietism (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 55f). The position of primary schoolteachers was strengthened, teacher seminaries were set up, and wages increased (Reference TønnessenTønnessen, 2011, 35f). The gradual democratization of Norwegian society meant that the population no longer consisted of mere subordinates but of citizens, who had to be educated accordingly (Reference DaleDale, 2008, 47f; Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 59ff). With the law on the allmueskole in the countryside (lov om allmueskolen på landet) from 1860, history and geography became part of the curriculum. The laws on the folkeskole (primary school) from 1889 continued this trend by turning history, geography, and natural science into obligatory subjects, and by increasing the number of hours of schooling. From 1889 onward, school directors (skoledirektørene) became the only supervisory authority for the schools. Bishops and the presidents of the dioceses (stiftsamtmenn) no longer had a say. Many school directors were politically active in the major movements of the time: the temperance movement and the nynorsk language movement (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 85ff). The replacement of the term allmueskole with the term folkeskole represented new ideas. From then on, schooling would contribute to creating national identity, culture, and pride. Elementary schooling would be for all people (Reference MediåsMediås, 2010, 28).

Overall, teachers and laymen acquired increased influence from 1850 onward, while the influence of the church weakened. State regulation and financing grew slowly but steadily. Christianity remained an important subject, but teachers replaced theologians in central positions (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 78ff).

Educational Expansion and the First Comprehensive School Reforms

Besides contributing to nation-building, education was now also considered a means for equalization and social integration. In the cities, three parallel school types had developed up to the 1850s and 1860s: first, the allmueskole, also called fattigskole (poor school), which taught Christianity, reading, writing, and numeracy to about 70–80 percent of each age group; second, the borgerskole/realskole, which taught modern languages, history, geography, and natural science in addition to the subjects taught in the allmueskole; third, the latinskole, which taught Latin, Greek, and sometimes Hebrew, leading to university.

This system was differentiated by social status and class and came under criticism in the 1840s and 1850s. In 1869, parliament attempted to create a universal three-year comprehensive primary school, but the law (lov om offentlige skoler for den høiere Almendannelse) did not have the intended effect. The quality of the allmueskole was so low that the upper class could not imagine sending their children there (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 68ff). The standard improved considerably in the ensuing decades. In the cities, schools with separate classes for the different age groups became usual. The allmueskoleloven from 1860 stipulated that all school districts with at least thirty children of school age had to build permanent school buildings, leading to the construction of several thousand schoolhouses. However, until the 1930s some children in Norway still only received irregular schooling in schools that did not have permanent school buildings but moved from village to village (omgangsskoler) (Reference TønnessenTønnessen, 2011, 34). This was due to Norway’s sparse population in some areas (Tables 2.1 and 2.2).

Table 2.1 Population in Norway, 1735–2015

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1735 | 616 109 |

| 1800 | 881 499 |

| 1850 | 1 384 149 |

| 1900 | 2 217 971 |

| 1920 | 2 616 274 |

| 1940 | 2 963 909 |

| 1950 | 3 249 954 |

| 1955 | 3 410 726 |

| 1960 | 3 567 707 |

| 1965 | 3 708 609 |

| 1970 | 3 863 221 |

| 1975 | 3 997 525 |

| 1980 | 4 078 900 |

| 2000 | 4 478 497 |

| 2015 | 5 165 802 |

Table 2.2 Norwegian resident population in densely and sparsely populated areas and per km2, 1845–1970

| Year | Total | Densely populated areas | Sparsely populated areas | Population in urban municipalities | Percentage of population in densely populated areas* | Population per km2** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1845 | 1 328 471 | 206 338 | 1 122 133 | 161 875 | 15.6 | 4.3 |

| 1855 | 1 490 047 | 252 308 | 1 237 739 | 197 815 | 16.9 | 4.8 |

| 1865 | 1 701 756 | 333 485 | 1 368 271 | 266 292 | 19.6 | 5.5 |

| 1875 | 1 806 900 | 440 273 | 1 366 627 | 326 420 | 24.4 | 5.9 |

| 1890 | 2 000 917 | 625 417 | 1 375 500 | 474 129 | 31.3 | 6.5 |

| 1900 | 2 240 032 | 800 198 | 1 439 834 | 627 650 | 35.7 | 7.3 |

| 1910 | 2 391 782 | 921 382 | 1 470 400 | 689 228 | 38.5 | 7.7 |

| 1920 | 2 649 775 | 1 200 020 | 1 449 755 | 785 404 | 45.3 | 8.6 |

| 1930 | 2 814 194 | 1 330 217 | 1 483 977 | 800 514 | 47.3 | 9.1 |

| 1946 | 3 156 950 | 1 581 901 | 1 575 049 | 884 097 | 50.1 | 10.2 |

| 1950 | 3 278 546 | 1 711 628 | 1 566 918 | 1 054 820 | 52.2 | 10.6 |

| 1960 | 3 591 234 | 2 052 634 | 1 538 600 | 1 152 377 | 57.2 | 11.6 |

| 1970 | 3 874 133 | 2 554 913 | 1 319 220 | 1 641 315 | 65.9 | 12.6 |

* Densely populated areas comprise urban municipalities as well as densely populated areas in rural municipalities. “The definition of a densely populated area has varied from time to time […]. In the censuses 1960 and 1970 a densely populated area was defined as a population cluster with at least 200 resident persons, where the distance between the houses generally did not exceed 50 metres” (SSB, 1978, 22).

In 1896, the law on secondary schooling (lov om den høyere skole) stipulated that a four-year lower-secondary school and a three-year upper-secondary school (gymnaset) should build consecutively on the first five years of the folkeskole, which lasted seven years. The first five years of the folkeskole thus became comprehensive, except for private preparatory classes. Lower-secondary schooling was no longer stratified into different tracks. This meant that the borgerskole and the latinskole merged into one school type at the lower-secondary level, now called høyere skole (higher school), which was more influenced by the borgerskole than by the Latin schools. The upper-secondary level, gymnaset, consisted of a natural science track, a linguistic-historical track, and a linguistic-historical track with Latin. The Latin school only survived as a track at the gymnas, and even this Latin track was under political pressure from the Liberal Party and the teachers at the folkeskole. They did not consider Latin a necessary component of upper-secondary education. The Conservative Party and the teachers of the gymnas only just managed to protect the track from abolition in 1896. The lower-secondary school remained popular among the middle class and the daughters of civil servants (Reference TønnessenTønnessen, 2011, 48f).

The development of comprehensive schooling from 1865 to 1896 was influenced by four main motives (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1974; Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 69ff). First, comparisons with the United States served as inspiration for a new kind of democratic school adjusted to modern needs. Second, comprehensive schooling was less costly than parallel schooling, especially for small municipalities. Finances were the main reason why some municipalities implemented comprehensive primary schools even before it was stipulated by law. Third, it was argued that comprehensive schooling in the first five years would increase the quality of schooling at the allmueskole/folkeskole. What it would do to the quality of secondary schooling was not a key concern. It was assumed that the influx of children from the upper and middle classes would increase school quality. All social classes would have an interest in the quality of the folkeskole; they would start to regard it as “their school” and would therefore be more willing to support it politically. Fourth, liberal supporters of the comprehensive school argued that parallel schooling led to a lack of respect and understanding between classes. This “class hate” was seen as a threat to national unity and solidarity (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 77). Only differences stemming from innate abilities were deemed legitimate. Social mobility had to be increased to mobilize the hidden talents of the population. Adversaries of school reforms also put forward arguments based on social class, but from a more moralizing perspective. They assumed that poverty was partly related to bad morals, worrying that children from “bad homes” would have a bad influence on the children of the upper and middle classes. They also argued that class differences would become more visible once children of different classes attended school together.

Besides the increased emphasis on education for the lower classes, there was a trend toward opening secondary schooling up for girls and women. In 1878, girls’ access to the lower-secondary school exam was regularized. From 1882, women could take the upper-secondary school exam (examen artium) and attend university, and from 1884, coeducation in lower-secondary schools was made possible (Reference MediåsMediås, 2010, 32). Female teachers could be employed as assistants in primary schools from 1860, and from 1872, they could take female teacher exams. After 1889, teacher seminaries were opened to women and they could be employed as regular teachers in the folkeskole (Reference MediåsMediås, 2010, 32).

Furthermore, special schools were introduced for disabled and neglected children. In 1881, a law on abnormskoler (“abnormal” schools) was passed (Reference TønnessenTønnessen, 2011, 46f). These schools also served to make the folkeskole more acceptable to the upper class, since they excluded some of the most difficult students from general schooling.

Finally, two additional school types were introduced. Specific to the Nordic context is the tradition of the folkehøyskole (people’s high school). These schools gave a general introduction to the national intellectual traditions but also offered practical training. Teenagers who had completed allmueskole/folkeskole could attend the folkehøyskole, usually for six months. Around the turn of the century, another school type developed, called framhaldsskole in the countryside and fortsettelsesskole (continuation school) in the cities. These schools gave teenagers who had finished folkeskole another option to prolong their education and taught both practical skills and general civic knowledge. Many female teachers supported this school type as an ideal secondary school for girls. In contrast to the folkehøyskole, these schools were not boarding schools and they were less ideological (Reference TønnessenTønnessen, 2011, 50f).

The Introduction of the Seven-Year Comprehensive School

In 1905, the union between Sweden and Norway was dissolved and Norway became independent. The early twentieth century was characterized by a range of reforms implemented by the Liberal Party government. The Liberal Party was still the largest one in parliament, but in 1912 the Labor Party received 26.5 percent of votes and became the second largest party.

In 1911, a committee (enhetsskolekomiteen) was put in place by the government to discuss comprehensive school reforms and a better interconnection between primary and secondary schooling. In 1913, the committee presented its proposal. The majority of the committee was of the opinion that comprehensive schooling entailed all children having the possibility to proceed to a secondary school. The minority contended that the competition between the folkeskole and the lower-secondary school in grades six and seven would have to be abolished to achieve fully comprehensive schooling throughout the folkeskole. The majority further suggested that if a model were to be introduced with seven years of folkeskole followed by two years of lower-secondary school, the curriculum of the folkeskole would have to be improved, notably with the introduction of a foreign language in grades six and seven (Reference DokkaDokka, 1988, 115ff; Reference MediåsMediås, 2010, 35f). In the following years, this was discussed further. The law on rural primary schools was changed in 1915 and the law on city primary schools in 1917. The minimum number of weeks of schooling was increased (Reference MediåsMediås, 2010, 36). The laws now stipulated that teaching should be conducted in students’ natural dialect and introduced local polls to choose the language form within a school district (Reference Almenningen, Almenningen, Roksvold, Sandøy and VikørAlmenningen, 2002a, 102).

The Labor Party became more active in education politics. Socialists and liberals cooperated in their attempt to prolong comprehensive schooling. There were two currents in Norwegian social democracy: the moderate Gjøstein current was concerned with opening the school system for the children of the working class and considered comprehensive schooling a step toward overcoming class divisions in education. Already in 1904, O. G. Gjøsteen suggested a ten-year comprehensive school. The other, more radical current, represented by Edvard Bull, was skeptical of the existing educational traditions and aimed at a more practical, alternative education, which should serve to create solidarity and be closer to the workers’ own culture (Reference SlagstadSlagstad, 2001, 388f; Reference TønnessenTønnessen, 2011, 57). The Bull current dominated prior to the Second World War. However, the Labor Party representative Johan Gjøstein, O. G. Gjøsteen’s brother, managed in 1920 to convince the Norwegian parliament to give financing only to lower-secondary schools that built upon seven years of folkeskole. This decision, which was taken against the votes of the Conservative Party and sections of the liberals, effectively prolonged comprehensive schooling by another two years, apart from a few private schools (Reference SlagstadSlagstad, 2001, 389). The parliamentary decision did not contain any details concerning the length of the lower-secondary school. In most municipalities, the lower-secondary school now lasted three years, but a proposal for shortening it to two years was debated (Reference DokkaDokka, 1988, 120ff; Reference MediåsMediås, 2010, 37). Seven years of comprehensive schooling were thus introduced in Norway at an early point compared to other Western countries.

The Reform Movement of the 1920s and 1930s

From the 1920s, an economic crisis set in and unemployment grew. The Labor Party became more radical and joined the Comintern for some years, leading to a party split. In 1920, the Farmers’ Party (today Senterpartiet, the Center Party) was founded. A time of political instability was ushered in, with shifting Liberal Party and Conservative Party governments. In 1933, the party of the Christian Democrats was founded as an additional party competing for the voters of the Liberal Party. In the 1930s, the Labor Party oriented its strategy more clearly toward parliamentary power. In 1935, the Labor Party and the Farmers’ Party formed a coalition government, which was based on an agreement including agricultural subsidies and investments to increase employment. This government remained formally in office until 1945. However, Norway was occupied by Nazi Germany in 1940. The five years (1935–40) of the first stable social-democratic government in Norway can be considered a transitional period from the Liberal Party regime to a social-democratic order (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 95ff).

In 1920, a parliamentary school commission was formed; it was short-lived. It had been put in place by a conservative government, and as a result, parliament refused to finance its work. In 1922, a new commission was created, this time with fewer conservative and more leftist members. This commission produced several proposals in the years from 1922 to 1927, which laid the ground for the school laws of the 1930s. The most important suggestion regarding comprehensive schooling was to reshape the secondary schools by introducing a three-year realskole and a five-year gymnas, both building on the comprehensive seven-year folkeskole. The two first years of realskole and gymnas should be combined, while the third year of realskole should be more practically oriented (Reference MyhreMyhre, 1971, 96).

In 1935, a law on secondary schooling (lov om høiere almenskoler) was passed (Reference MyhreMyhre, 1971, 97). The law regularized the seven-year folkeskole. Some secondary schoolteachers had wished for differentiation after the fifth or sixth grade, but this proposal failed (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 122). The lower-secondary realskole had its own final examination but also led to upper-secondary schooling in the gymnas. Secondary schools with common realskole and gymnas classes on the lower-secondary level were made possible. Two-, three-, and four-year realskoler existed, as well as five- and six-year gymnas. Most municipalities introduced five-year secondary schooling, consisting of two common years in realskole and gymnas, and then a more practical third realskole year, or three academically oriented gymnas years. In the cities, a nine-year comprehensive school was thus beginning to take shape. In the countryside, the two-year continuation school (framhaldsskole) still existed as a parallel school type (Reference Seidenfaden, Körner and SeidenfadenSeidenfaden, 1977, 8).

In 1936, laws on primary schools in the countryside and in the cities were passed (landsskuleloven and lov om folkeskolen i kjøpstædene). These laws introduced stricter rules regarding the division of age groups, minimum standards with respect to the curriculum, and a higher number of school hours. Centralization of schools became an important aim. The number of schools without any division into age groups was lowered from 1060 to 601 between 1935–6 and 1945 (Reference MyhreMyhre, 1971, 100). This development created some urban-rural tension, as it led to longer journeys to school for students in sparsely populated areas (Reference Seidenfaden, Körner and SeidenfadenSeidenfaden, 1977, 10; Table 2.2).

From 1935, a planning committee (plankomité) consisting of representatives of the primary and the secondary school sector worked on a range of pedagogical questions. In addition, a committee was put in place to devise a new general curriculum (normalplankomiteen) from 1936 to 1939. Reformers were influenced by the ideas of the German Arbeitsschule movement. To them, there should be practical activity, individualized teaching, and teamwork in schools. The children’s interests should be considered (Reference MyhreMyhre, 1971, 95ff). Use of grades was greatly reduced, and grades were abolished entirely in the first three years of the folkeskole (Reference Tønnessen, Telhaug, Skagen and TillerTønnessen/Telhaug, 1996). The aim became to foster intrinsic motivation (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 18f). Subjects such as physical education, needlework, or housekeeping, the latter of which were taught only to girls, were strengthened (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 111ff).

The curriculum of 1939 was in accordance with a positivistic approach to science and was the only curriculum in Norwegian history to be written almost like a science report (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 125ff). The curriculum was made binding for all municipalities, meaning that they could no longer decide freely how many hours to allocate to the different subjects. The geographical variation that had developed during the period of Liberal Party government was now regarded as undesirable (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 132ff).

The leaders of the primary schoolteachers’ organizations became central advisors to the ministry and were among the architects of the new curriculum and laws (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 111). The abolition of private teachers’ colleges was an important aim of the labor movement, also because many of them were run by Christian organizations. In 1938, only one private teachers’ college remained (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 120f). There was also a relative decrease in private schools. Around 1900, 8 percent of the students went to private schools. In 1940, it was less than 1 percent (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 121; Reference TønnessenTønnessen, 2011, 54).

In 1937, a language reform bill was passed by the Labor Party, the Farmers’ Party, and the Liberal Party, against the votes of the Conservative Party and a few Christian democrats; this brought the two written language forms closer to each other (Reference RamsdalRamsdal, 1979, 17ff). The aim of the Labor Party and the center parties was now to work toward the merging of the two forms into a common standard, known as samnorsk, which would be based on people’s actual way of speaking. There was no agreement about this within the language movement. The reform led to an increase in school districts using nynorsk. By 1944, 34.1 percent of Norwegian schools were teaching in nynorsk – the highest percentage ever (Reference Almenningen, Almenningen, Roksvold, Sandøy and VikørAlmenningen, 2002b, 125).

Overall, the reforms show that for the Labor Party and Farmers’ Party government formed in 1935 educational expansion was an important aim. The state took over more and more of the education sector. The amount of financing from central government kept rising. In exchange, the government claimed increased influence.

Warming Up for New Reforms: The 1940s and Early 1950s

During the German occupation from 1940 to 1945, the reform processes were disrupted. The country was governed by German Nazis and a fascist minority of Norwegians (Reference OlstadOlstad, 2010, 111). In 1942, Vidkun Quisling, the leader of the Norwegian fascist party Nasjonal Samling, became prime minister. Many civic organizations and the state church refused to cooperate with the Nazi regime. Teachers played an important part in the resistance. In 1942, the Gleichschaltung (forced political alignment) of teachers’ organizations and the introduction of a national youth service led to parent and teacher protests and arrests. The Quisling government had to give up its attempt to introduce a Nazi teachers’ organization (Reference DokkaDokka, 1988, 149ff; Reference MediåsMediås, 2010, 42). When the war was over, Norwegians’ relationship with Germany had suffered massive damage.

After the war, a group of young Labor Party leaders came to office under Prime Minister Einar Gerhardsen. They started their work with optimism and boldness. The common program signed by all parties after the war (Fellesprogrammet) underlined the importance of cooperation and national integration. Industrialization, economic growth, equal opportunities, rights, and security for everyone became major goals. The new government aimed at strong regulation of the economy, but opposition from the political right and from international bodies contributed to moderation. However, the state remained strong and corporatist channels became important (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 138ff).

The debate on school structure started again immediately after the war. The common program of 1945 stated that the whole education system should be coordinated so that all elements should interlock naturally (Reference MediåsMediås, 2010, 42). This was related to developments abroad. In 1944, the British Butler Act introduced compulsory schooling for five- to fifteen-year-olds. The French Paul Langevin Commission in 1947 discussed the introduction of compulsory schooling up to age nineteen. In Sweden, a school commission, founded in 1946, suggested in 1948 creating a nine-year comprehensive school, the introduction of which was decided by the Swedish parliament in 1950 (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 23f). The Norwegian Labor Party politician Helge Sivertsen, who was state secretary at the Ministry of Education from 1947 to 1956 and minister of education from 1960 to 1965, was present at the Swedish parliament during this debate (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 175).

In 1947, a commission (Samordningsnemnda for skoleverket) was put in place to discuss the internal coordination of the education system (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 24ff). The first minister of education after the war, Kåre Fostervoll from the Labor Party, was none too keen on far-reaching changes. His successor, Lars Moen, who was minister until 1953, also belonged to the “old school” of the Labor Party and supported the reforms of the 1930s (Reference Telhaug and MediåsTelhaug/Mediås, 2003, 147). However, in 1949 the commission suggested making the first year of the framhaldsskole obligatory for students who did not attend the realskole (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 25).

From 1951 on, the Ministry of Education supported reform of lower-secondary schools, involving a weakening of organizational differentiation. In 1952, the commission of 1947 published its last report (Sammenfatning og utsyn), in which it drafted the possibility of creating a new lower-secondary school with parallel tracks for vocational and general education (linjedelt ungdomsskole). The report stated,

No other institution has meant as much as the folkeskole in terms of the equalization of status and class differences within the Norwegian people and to create togetherness and comradeship between children of different layers of society. […] The community in the children’s school is an important social and national factor that should be strengthened by letting this community continue during the time of youth which is so decisive for the attitude towards life.

The report was not clear with respect to the fate of the older school types. One of the commissions’ members, Principal Heli, made it clear that he thought that these old school types should be replaced (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 27).

By 1952–3, the Labor Party started working toward a new, internally tracked youth school (ungdomsskole). Its manifesto from 1953 stated that the short-term goal was to strengthen the folkeskole in the countryside as well as the framhaldsskole, so that eight years of education would become the rule. The next step would be to create a comprehensive youth school to replace the old school types of framhaldsskole and realskole. To facilitate this, municipalities should build common school buildings for different school types (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 28ff).

In 1953, Birger Bergersen became minister of education. He had been an ambassador in Sweden and had witnessed the reform movement there. From this point on, the ministry began arguing for a comprehensive school policy, as expressed in its white paper on measures to strengthen the school system (St. meld. nr. 9 [1954], Om tiltak til styrking av skoleverket).Footnote 1

In the fall of 1954, this white paper (St. meld. nr. 9) was discussed in parliament. Reference TelhaugTelhaug (1969, 32) points out that “the relations between the minister and the political opposition were still characterized by an amount of cordiality one would normally not associate with parliamentary debates.” The chair of the Church and Education Committee in parliament, Smitt Ingebretsen, a member of the Conservative Party, called the minister of education a “wise man” and thought it meant much “to be able to dream together.” The minister in turn found listening to the opposition’s speakers “encouraging and stimulating” (Forhandlinger i Stortinget, October 12, 1954, 2249, 2265f). However, parliament was not decided on the question of a new comprehensive lower-secondary school. Everyone agreed that experiments were a good idea, and some members of the Labor Party argued for a new ungdomsskole, but the details of such a school were not discussed. Reference TelhaugTelhaug (1969, 33) is of the opinion that parliament’s position was rather hesitant. Most representatives were worried about the bad condition of the folkeskole, especially in the countryside. Parliament was less unhappy with the realskole and framhaldsskole. Nonetheless, the minister, Birger Bergensen, as well as the state secretary, Helge Sivertsen, were enthusiastic about reforms (Reference TelhaugTelhaug, 1969, 33ff). The changes they ushered in are discussed in detail in the rest of this book.

Schooling in Prussia/North Rhine–Westphalia up to the 1950s

Prussian State-Building and the Education System

After the Congress of Vienna, the Rhineland and Westphalia became Prussian provinces (Reference NonnNonn, 2009, 17ff). In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Prussia, Volksschulen (primary schools) were an element of state-building and mostly forced onto the population from above (Reference FriedeburgFriedeburg, 1992, 29ff). Secondary schooling was also linked more clearly to the interests of the state through the introduction of state exams and of the Prussian Abitur exam in 1788 (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 33f).

The defeat administered by Napoleon’s army in 1806–7 led to reforms in the Prussian state. The aim was controlled modernization from above (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 29; Reference Hohendahl and VosskampHohendahl, 1982). Education became an important political field. Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al. (2009, 33ff) identify three main tendencies in the Prussian education reforms of the early nineteenth century. The first was the linkage of tertiary education to the functions of the state. In 1810, the philosophical state exam for secondary schoolteachers was introduced. In 1817, hierarchically ordered career paths based on educational qualifications were introduced within the state bureaucracy (Laufbahnwesen).

The second tendency was the increased institutional separation of elementary and secondary schooling. In 1810, ninety-one Latin schools, now called Gymnasien, were recognized as upper-secondary schools – among a mass of different institutions of varying quality. In 1834, the Abitur exam was made obligatory for civil servants. The old status privileges of the nobility were thereby restricted, but the regulation had a social closure effect on the sons of the lower classes. Social exclusivity was expressed through a focus on classical languages, which made up at least 40 percent of the curriculum (Reference Herrlitz, Weiland and WinkelHerrlitz et al., 2003, 36ff).

Table 2.3 Population in the area of today’s NRW, 1816–2013

The third tendency was the development of separate status groups among teachers. Primary schoolteachers (Volksschullehrer) received a two- to three-year education from teacher seminaries, for which final exams were introduced in 1826. Secondary schoolteachers studied at a university for at least three years and developed into a respected group of civil servants. The two groups were far removed from each other socially (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 40ff).

The liberal Prussian reformer, Johann Wilhelm Süvern, introduced a reform proposal in 1819. It suggested a ladder system of education consisting of a primary stage and a lower- and an upper-secondary stage. All public schools should impart general humanist education and infuse Prussian youth with a “devout love for king and state” (Reference Süvern, Herrlitz, Weiland and WinkelSüvern, 2003 [1819], 21). Süvern assumed that the primary stage would be sufficient for the educational needs of the lower class. The lower-secondary stage would lead up to a point where youths would either start training in a trade or continue their academic education in upper-secondary schooling at a Gymnasium (Reference Süvern, Herrlitz, Weiland and WinkelSüvern, 2003 [1819], 22). Ludolph von Beckedorff, who took over the primary school department (Volksschulreferat) at the Prussian Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs in 1820, criticized Süvern’s proposal, arguing that separate schools were needed for children of peasants, townspeople (Bürger), and scholars (Gelehrte). These status groups, he claimed, were “different, but equally honorable” (Reference SchweimSchweim, 1966, 229). Pretending anything else would only create discontent. All children should be taught the same in terms of religion and morals but not in terms of knowledge (Reference SchweimSchweim, 1966, 222ff). In other words, Beckedorff argued that political stability could only be safeguarded if educational opportunities remained restricted. Süvern’s proposal failed (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 61).

Despite the change in the political climate after 1819, the primary school system continued to expand. Compulsory schooling was enforced gradually, and enrolment rates were higher than in many other Western countries (Reference Herrlitz, Weiland and WinkelHerrlitz et al., 2003, 49ff; Reference NonnNonn, 2009, 42f; see critical remarks in Reference Leschinsky and RoederLeschinsky/Roeder, 1983, 139).

State-Church Conflicts in Prussian Education Politics

A major conflict between the Prussian government and its western provinces of Westphalia and Rhineland was based on the denominational divide. The majority of the population in these provinces was Catholic, while Prussian civil servants were mainly Protestants (Table 2.4; Reference Reulecke, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeReulecke, 1995, 111). The Prussian state had been defined as a Protestant state, and Catholics were discriminated against in the state administration (Reference SchmittSchmitt, 1989, 37). In 1871, the German Reich was formed under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck. The German Reich was a federal state, dominated by its largest member, Prussia. Most men over twenty-five received the right to vote for the new parliament of the German Reich, the Reichstag. Within this new state, the Catholics represented a minority, consisting mainly of Catholic workers and the old Catholic middle classes, who were opposed to the Protestant state and business elites. The denominational divide thus coincided with territorial, social, and cultural divides (Reference SchmittSchmitt, 1989, 49). In 1870, the ultramontane Center Party (Zentrum) was founded, which was strong in the Rhineland and Westphalia. The Center Party was a workers’ party to some extent, but more importantly it defended the rights of the Catholic Church and milieu against the Protestant state (Reference MannMann, 1973, 421ff). Political Catholicism was opposed to liberalism, capitalism, and socialism, which were all seen as expressions of Protestantism. As Reference SchmittSchmitt (1989, 49) points out, this “political Protestantism” was, however, “a Catholic myth.” There was no foundation for a united political Protestant movement. Rather, Protestants were divided internally into liberal and conservative, and later also social-democratic, currents.

Table 2.4 Percentages of Protestants and Roman Catholics in the German population, 1871–1987

During the 1870s, the conflicts between the Prussian state and the Catholic Church culminated in the Kulturkampf (cultural struggle) (Reference MannMann, 1973, 441ff; Reference NonnNonn, 2009, 60f). Bismarck, supported by Protestant conservatives and nationalist liberals, fought the Catholic Church and its party fiercely for about ten years. He abolished the Jesuit order, closed church seminaries, and deposed the bishops of Cologne, Paderborn, and Münster from office. He aimed at introducing state supervision of schooling with the school supervision law of 1872 (Schulaufsichtsgesetz). On the curriculum, religious education was reduced in 1871, and subjects such as history, geography, and natural sciences were increased (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 104ff). In 1876, a regulation was passed according to which Christian education could only be taught by state-licensed teachers or priests. Bismarck wanted to overcome denominational schooling by introducing Simultanschulen (simultaneous schools), in which children of different denominations were taught together. These attempts were hugely unpopular with the Catholic Church and the Center Party. They were also unsuccessful: between 1886 and 1906, 90 percent of Catholic children and 95 percent of Protestant children were still taught in Volksschulen of their own denomination (Bekenntnisschulen). School supervision remained largely in the hands of clergymen and was regulated inconsistently until 1918 (Reference Kuhlemann and BergKuhlemann, 1991, 184).

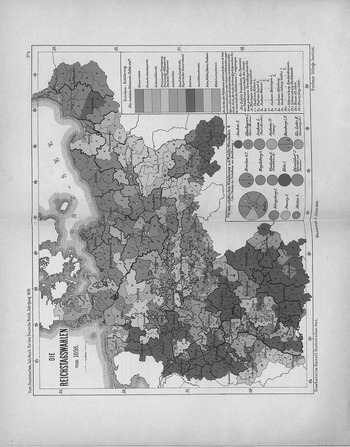

The effect of the cultural struggle was the opposite of what was intended: the Catholic milieu was welded together more strongly, and the majority of the Catholic population stood behind the Center Party (Reference NipperdeyNipperdey, 1991, 439ff; Reference NonnNonn, 2009, 61; Reference Reulecke, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeReulecke, 1995, 112; Reference SchmittSchmitt, 1989). It received the most votes of all parties in Westphalia and the Rhineland until 1933 (Figure 2.1; Reference NonnNonn, 2009, 60). In 1878, Bismarck relented, and in the following years, many anti-Catholic regulations were withdrawn. During the 1880s and 1890s, several Catholic mass organizations were founded, including teachers’ organizations. The relations between the denominations continued to be characterized by mistrust (Reference Reulecke, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeReulecke, 1995, 113ff; Reference TymisterTymister, 1965).

Figure 2.1 Results of the elections to the German Reichstag in 1898.

Note: The dark gray shading shows the areas where the Catholic Center Party (Zentrum) received the highest percentage of votes of all parties.

Educational Expansion: Liberal and Social-Democratic Demands

Protestant liberals and early socialists had their political center in Cologne (Reference Elkar, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeElkar, 1995, 64f). On March 3, 1848, 5000 people gathered in front of Cologne city hall, asking for civil liberties and for the “complete education of all children at the public’s expense” (Reference Elkar, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeElkar, 1995, 69). Many cities in the region became staging grounds for violent conflicts (Reference Elkar, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeElkar, 1995, 69ff). In the aftermath of the revolution, Prussia introduced universal suffrage, but under a three-class system of voting (Reference MannMann, 1973, 260).

In September 1848, the General German Teachers’ Association (Allgemeiner Deutscher Lehrerverein) was established in Eisenach. Liberal primary schoolteachers demanded a ladder system of education, in which the Volksschule would be the first link. They were against tuition fees and private schools and for the opening of secondary schools to the sons of the lower class. They asked for better wages, working conditions, education, and social security for teachers, and they thought that clergymen should no longer have the right to supervise the schools (Reference Herrlitz, Weiland and WinkelHerrlitz et al., 2003, 22f; Reference TymisterTymister, 1965, 31f). In response, the Prussian Ministry issued the Stiehl regulations of 1854. These aimed at putting a stop to teachers’ organizations and demands. Teacher seminaries were strictly regulated and teaching any “abstractions” or “pedagogy” was banned (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 60f). Nevertheless, primary schoolteachers continued to organize and to support comprehensive school reforms, including the abolition of preparatory primary schools (Reference Kuhlemann and BergKuhlemann, 1991, 191).

The introduction of modern secondary education created debates. Realschulen had been officially accredited during the 1830s (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 63ff). After the revolution, the Realschulen were considered a “tool of destructive liberalism” by the bureaucracy (Reference WieseWiese, 1886, 214, quoted in Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 64). However, the Realschule had many advocates from the economic section of the middle and upper classes (Wirtschaftsbürgertum). In 1859, the nine-year Realschule 1. Ordnung (from 1882 called Realgymnasium) was introduced. Most Realschulen taught Latin. Only the capacity to speak Latin would give one “the feeling of belonging to the recognized educated class,” as one deputy put it in the House of Deputies (Haus der Abgeordneten, 1882, quoted in Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 64). Until the 1880s, the humanist Gymnasium, which had the support of the academic elite and civil servants (Bildungsbürgertum), kept its leading position. This school type was attended by 60–70 percent of secondary school students (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 63ff). During the 1880s, educational expansion was channeled by the expansion of Latin-free Realschulen and Oberrealschulen (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 79f).

In 1900, a compromise was reached between the supporters of modern and classical education. Realgymnasien, Oberrealschulen, and humanistische Gymnasien were put on equal terms, and their final Abitur exams were granted the same entitlements (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 74ff). The humanist Gymnasium lost its leading position, and its share of secondary boys’ schools dropped from 59 percent in 1900 to 39 percent in 1918, and 29 percent at the end of the Weimar Republic (Reference Albisetti, Lundgreen and BergAlbisetti/Lundgreen, 1991, 246). The percentage of eleven- to nineteen-year-old boys attending secondary schools increased from around 5 percent to over 10 percent from the 1890s to the 1930s (Reference Nath, Apel, Kemnitz and SandfuchsNath, 2001, 28).

Another liberal demand was access to public education for girls and women. From the late 1880s until 1908, more than thirty educational institutions were founded by the women’s movement in the German Reich to prepare girls for the Abitur exam as external examinees. Many girls of the middle and upper classes attended private Mittelschulen. These were Volksschulen with at least five ascending grades, a maximum of fifty students per class and an obligatory foreign language. These private middle schools often offered several foreign languages, in some cases even Latin and Greek. The state did not cover the financing of the middle schools (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 109; Reference Kuhlemann and BergKuhlemann, 1991, 188ff, 199ff). In the Rhineland and Westphalia, many girls attended Catholic private schools that had been developed by Catholic female orders (Reference SackSack, 1998, 30). In 1908, a regulated public-school path to the Abitur was finally created for girls. The ten-year girls’ school was termed Lyzeum and prepared girls for an upper-secondary education as teachers, for general “women’s education” at a Frauenschule (women’s school), or for a three-year preparatory course for the Abitur exam. The introduction of a track to the Abitur exam was only possible if the same institution also offered a Frauenschule. Many schools could not afford to offer all tracks; as a result, in 1912, only 3.6 percent of the students at the Lyzeum was taken into the tracks preparing girls for university (Reference Kraul and BergKraul, 1991, 289).

State expenses for primary schooling increased, but there were large urban-rural differences. Between 1886 and 1911, the number of schools separating the age groups expanded, but in the countryside, 39 percent of the Volksschulen were still one-class schools in 1911, compared with 8 percent in the cities (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 105). In 1883, in the rural East Westphalian district of Minden, one teacher had to teach between 120 and 200 children in 71 percent of the primary schools (Reference Kuhlemann and BergKuhlemann, 1991, 195ff). From the 1880s, the Prussian state attempted to combat the differences by introducing maximum requirements for class size, namely eighty students per class. A “school compromise” between the conservatives, the national liberals, and the Center Party in 1906 ended the landed property owners’ exemption from paying for school financing (Reference Kuhlemann and BergKuhlemann, 1991, 181). Volksschule teachers’ wages increased substantially (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 106). In 1885 and 1890, primary teachers’ pensions and survivors’ pensions were regulated, so elementary schoolteachers could now be considered a “consolidated stratum of lower civil servants” (Reference NipperdeyNipperdey, 1991, 543; see also Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 106).

Rhineland and Westphalia were among the most industrialized, urbanized, and populated Prussian provinces (Tables 2.3 and 2.5; Reference NonnNonn, 2009, 47ff; Reference Reulecke, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeReulecke, 1995, 87). Until the 1890s, socialist ideas gained little ground, as many workers preferred the Catholic and Protestant associations (Reference Reulecke, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeReulecke, 1995, 103). In 1875, the Socialist Workers’ Party was founded in Gotha (Reference WalterWalter, 2011, 13f). Bismarck’s anti-socialist law criminalized social-democratic organizations until 1890 (Reference MannMann, 1973, 444ff). From 1890, the party called itself Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party of Germany) and started to grow. By 1912, it had become the largest party in Germany, receiving 34.5 percent of the vote in the Reichstag elections (Reference WalterWalter, 2011, 27). The party was strongest in the northern cities and in some central industrial areas but weak in the east and south, and in Westphalia and the Rhineland (Reference WalterWalter, 2011, 28, 38). The Center Party remained strong in the region (Reference Reulecke, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeReulecke, 1995, 117).

Table 2.5 German population in rural and urban municipalities (in percentages) and per km2, 1875–2000

Education was important for the social democrats (Reference WalterWalter, 2011, 35). They used the term “comprehensive school” (Einheitsschule) from 1903 on. Heinrich Schulze, member of the Reichstag and primary schoolteacher, developed social democracy’s school program. Published in an extended version in 1911, it suggested preschools for all four- to seven-year-olds, followed by a comprehensive school for the eight- to fourteen-year-olds, and the abolition of private primary schools (Reference Schulze, Herrlitz, Weiland and WinkelSchulze, 2003 [1911], 29).

Some social democrats also supported experiments with the allgemeine Fortbildungsschule (general further education school) (Reference Kuhlemann and BergKuhlemann, 1991, 191). These schools were suggested by the liberal school reformer Georg Kerschensteiner and were an attempt to get fourteen- to eighteen-year-old working class youths off the streets (Reference KerschensteinerKerschensteiner, 1901). Kerschensteiner later contributed to the development of Berufsschulen (vocational schools) and to the Arbeitsschule principles: the Arbeitsschule should include practical training and students should be encouraged to think for themselves and be active and creative learners. Toward the end of the German Reich, many new ideas came into circulation (Reference Kuhlemann and BergKuhlemann, 1991, 191f).

Reform Struggles during the Weimar Republic

Although no battles took place in the Rhineland and Westphalia, the First World War greatly affected the region. From 1916 to 1917, food shortages worsened and “hunger demonstrations” became frequent (Reference Brunn, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeBrunn, 1995, 130ff). The social democrats, the majority of whom had supported the war credits financing Germany’s participation in the First World War, were split. In 1917, a group of social democrats who had been expelled from the SPD founded the Independent Social Democratic Party (Reference WalterWalter, 2011, 46ff; Reference WehlerWehler, 2003, 110ff).

The November Revolution of 1918 was initiated by a mutiny in the German navy. On November 9, 1918, a republic was declared by the social democrat Philip Scheidemann. From November 10, 1918, until February 11, 1919, Germany was governed by the Council of People’s Deputies, consisting of politicians of both social-democratic parties, and supported by the workers’, soldiers’, and farmers’ councils (Reference WehlerWehler, 2003, 190ff). The SPD won the first elections and a coalition government consisting of the SPD, the second-largest Center Party, and the social liberal German Democratic Party (DDP) was created.

From the outset, the Weimar Republic was destabilized by the fact that the power bases of the old elites remained largely intact. In addition, many workers turned their backs on the SPD and joined more radical socialist, communist, or syndicalist organizations (Reference BluhmBluhm, 2014). The early 1920s were characterized by political instability and violent struggles (Reference Brunn, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeBrunn, 1995, 141ff; Reference WehlerWehler, 2003, 397ff). The Dawes Plan of 1924 brought some stability to the Rhineland and Westphalia (Reference Brunn, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeBrunn, 1995, 142ff).

The administrative elites of the education system retained their positions. Few of the civil servants in the Prussian Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs were social democrats. The most important reforms of the Weimar Republic were completed during the first half of 1920; the elections of June 1920 weakened social democracy and the liberal parties. The SPD stood for the separation of church and school, the introduction of a comprehensive school with a minimum of eight years, and the abolition of private schools and tuition fees. Only a fraction of this could be included in the articles pertaining to schools in the new constitution (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 118ff).

An important milestone was the primary school law (Grundschulgesetz) of April 1920, which abolished public preparatory primary schools from 1924 to 1925 and private ones from 1929 to 1930 and introduced the four-year obligatory and comprehensive primary school for all. The law was passed with the votes of all parties, except for the conservative Deutschnationale Volkspartei (German National People’s Party). In the following years, opponents of comprehensive primary schooling fought for exemptions. In 1925, the law was changed so that “particularly capable children” could begin their secondary education after just three years. The SPD, the DDP, and the organization of primary schoolteachers fought these exemptions. The Center Party consented to the four-year primary school (Reference BöllingBölling, 1978, 138f). By 1931, 95.8 percent of secondary school students had completed the public primary school (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 118ff). In 1936, the National Socialists eliminated the last of the private preparatory institutions (Reference Zymek, Langewiesche and TenorthZymek, 1989, 168, 194).

The state-church conflict about the abolition of denominational primary schools “surmounted any other school-political conflicts in intensity and extent” (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 126). The clergy’s right to supervise the Volksschule was abolished, but the separation of school and church was not achieved. The Weimar school compromise entailed that a Simultanschule, a Christian school for children of both denominations, should become the rule, while denominational schools would be possible as an exception. The SPD opposed the Simultanschule and preferred a complete secularization but had to make do with the possibility of establishing secularized Weltanschauungsschulen (worldview schools). The Center Party, Catholic and Protestant parents’ associations, the conservative parties, and the churches opposed the abolition of denominational schools. The German National People’s Party and the nationalist liberal German People’s Party (Deutsche Volkspartei) attempted several times to pass a law that would make denominational schools the rule again. The ongoing conflict led to the preservation of the status quo and the Simultanschule was not introduced at a general level (Reference BöllingBölling, 1978, 137ff; Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 126f).

Prussian girls’ education was reformed further in 1923 with the introduction of the Oberlyzeum. By 1931, one-fourth of the Prussian Abitur graduates were female (Reference Zymek, Langewiesche and TenorthZymek, 1989, 172). Differentiation into separate higher secondary school types continued among the boys’ schools. With the Gymnasium, the Realgymnasium, the Reformgymnasium, the Reformrealgymnasium of the new and old type, the Oberrealschule, and the Deutsche Oberschule, the number of school types was now confusing, even for contemporaries. These school types differed mainly with regard to which languages were taught for how many hours and in which order. Mixed forms were common (Reference Zymek, Langewiesche and TenorthZymek, 1989, 172f).

Nazi Politics of Educational Restriction

Toward the end of the Weimar Republic, Chancellor Brüning’s austerity measures led to a deterioration in teachers’ socioeconomic conditions. Unemployment among young primary schoolteachers grew and wages decreased by up to 28.8 percent (Reference BöllingBölling, 1978, 200). Teachers began to turn against the democratic state. Like other white-collar and middle-class groups, they were overrepresented in the membership of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, NSDAP) (Reference BöllingBölling, 1978, 204). When the Nazis came to power in 1933, there was not much opposition to forcible coordination (Gleichschaltung) of teachers’ organizations. The National Socialist Teachers’ Union organized 95 percent of the teaching force by December 1933 (Reference Brunn, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeBrunn, 1995, 166; Reference Müller-Rolli, Langewiesche and TenorthMüller-Rolli, 1989, 253). Some courageous resistance was shown by members of the Communist Party, socialists and social democrats, and some representatives of the Catholic and Protestant churches, but by 1936 most resistance was broken (Reference Brunn, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeBrunn, 1995, 163ff; Reference NonnNonn, 2009, 66).

Within the cultural ministries and the schools administration, the NSDAP made sure to secure its position, and many school inspectors were fired straightaway. National Socialist teacher schools were created. These were boarding schools characterized by strict discipline and ideological indoctrination (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 145ff).

Despite the National Socialist claim that education should become independent of social background, the opposite was the case. In 1933, the law against overcrowding of the German schools and colleges (Gesetz gegen die Überfüllung der deutschen Schulen und Hochschulen) was passed. The law excluded Jewish Abitur graduates from the universities and limited the share of female university entrants to 10 percent (Reference Zymek, Langewiesche and TenorthZymek, 1989, 188f). National Socialist elite schools were created to produce the future cadres for the party (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 148). In 1938, the Reichschulpflichtgesetz made schooling obligatory from age six to eighteen – first in the Volksschule, then in vocational schools. New curricula turned the Oberschule into the main higher secondary school type and shortened it to eight years but left the humanist Gymnasium intact. The lower-secondary, or middle, school system was also consolidated. Already in March 1931, the Mittlere Reife had been introduced as a school-leaving certificate after the tenth school year, with relevance for entrance to middle positions in administration, trade, and industry (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 127ff). In 1938, various lower-secondary school types were subsumed under two remaining types: the six-year Prussian middle school and a four-year upper middle school that built on the sixth grade of the Volksschule (Reference Zymek, Langewiesche and TenorthZymek, 1989, 197ff).

In accordance with the National Socialist concordat with the Vatican of 1933, denominational schooling was at first left intact. However, religious education in schools was restricted, the clergy’s influence was curtailed, and by 1941 most denominational schools had been turned into Gemeinschaftsschulen (common schools) for both denominations. The abolition of private schools was another element of these anti-church politics (Reference Zymek, Langewiesche and TenorthZymek, 1989, 200f).

Jewish children were gradually excluded from public education. After the pogroms of November 9–10, 1938, Jewish emigration accelerated, and the number of Jewish schoolchildren shrank by two-thirds within a year. Deportations of Jews to concentration camps began in November 1938 and accelerated from 1942. From July 1942, all remaining Jewish schools were shut down (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 149ff; Reference Zymek, Langewiesche and TenorthZymek, 1989, 199f). On April 17, 1945, the National Socialist regime in Rhineland and Westphalia finally broke down (Reference Brunn, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeBrunn, 1995, 174f).

Restoration or Reform? The Late 1940s and 1950s

The initial postwar years were hard. Millions of refugees were looking for shelter and food (Reference Brunn, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeBrunn, 1995, 176ff; Reference NonnNonn, 2009, 72ff). There was a great lack of usable schools and politically trustworthy teachers. Denazification attempts were conducted in a pragmatic way. Many civil servants of the Nazi regime kept their jobs (Reference Brunn, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeBrunn, 1995, 176ff).

On August 23, 1946, the federal state of North Rhine–Westphalia was founded by a British ordinance. It comprised Westphalia and the northern part of the Rhineland, which were part of the British occupation zone; in January 1947, the small Lippe region was added. The SPD, the Center Party, and the Communist Party (KPD) were re-founded. The Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) were newly founded parties.

After the first federal state elections in 1947, Karl Arnold from the CDU, a former Center Party member, became Ministerpräsident, meaning the head of the government of NRW (Reference Brunn, Briesen, Brunn, Elkar and ReuleckeBrunn, 1995, 188ff). Arnold remained in this position until 1956. At first, he governed in a coalition including the Center Party, the SPD, and, until 1948, even the KPD. From 1950 to 1956, the CDU formed a coalition with the Center Party, which from 1954 to 1956 included the FDP. Arnold was a representative of the wage-earner wing of the CDU. He preferred a coalition with the SPD to a coalition with the FDP, but due to different opinions about denominational schooling the early coalition with the SPD broke down. Later, a CDU-SPD coalition in NRW was impeded by disagreements on the national level (Reference DüdingDüding, 2008, 291, 313; Reference NonnNonn, 2009, 84f).

In 1945, the SPD and the KPD published a declaration for a comprehensive school system and the separation of church and school. In 1947, the Allied Control Council published Directive No. 54, which was inspired by the American Zook Commission and suggested the introduction of a ladder system of education with comprehensive schooling at the lower-secondary level and better civic education (Reference Herrlitz, Weiland and WinkelAlliierte Kontrollbehörde, 2003 [1947]). Germans’ predisposition for National Socialist ideology was partly explained with the division between primary education and elitist secondary education (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 158f).

Between 1947 and 1948, several German federal states attempted to reform the school system. A prolongation of the comprehensive primary school to six years was suggested by a Christian democratic minister in Württemberg-Baden and implemented in Hamburg, Bremen, and Schleswig-Holstein by social-democratic ministers – it was later withdrawn by conservative-liberal governments. In Hessen and Niedersachsen, there were plans for comprehensive schools, and in Berlin a twelve-year comprehensive school was suggested. However, the reformers were mainly remnants of the Weimar reform coalition and had been scattered by emigration, oppression, and war. The division of Germany and the intensification of the Cold War weakened them further. Most of the suggested reforms were not carried through. Instead, the Weimar school system was restored. The Düsseldorf Agreement of 1955 confirmed this development. In this agreement, the ministers of education of the federal states agreed that all school-leaving certificates would be recognized in all of Germany. Higher secondary schools should now all be called Gymnasien, and future school experiments should not threaten the parallel school structure (Reference FriedeburgFriedeburg, 1992, 321ff; Reference Furck, Führ and FurckFurck, 1998a, 248; Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 160f).

The denominational separation of teacher training and primary schooling remained a contested topic. When the NRW constitution was passed in 1950, denominational schooling was restored (Reference DüdingDüding, 2008, 267ff; Reference Furck, Führ and FurckFurck, 1998b). The churches played an important role in legitimizing the anti-reform stance of the 1950s. The secularization of the Volksschule and attempts to integrate the school system were labeled equally “un-Christian” as the Nazi reform proposals (Reference Furck, Führ and FurckFurck, 1998a, 249; Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 158ff; Chapter 5).

The 1950s witnessed careful attempts to put educational expansion and reform on the agenda. It was now asserted more frequently that the education system did not produce enough qualified labor. The idea of equality of opportunity gained ground (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 173). In 1951, the Mittelschule was renamed Realschule by the CDU minister of culture of NRW, Christine Teusch, who argued that it should not be mistaken for a school for those with “a middle amount of talent” but should impart its graduates with increased competencies (Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs of NRW, 1951, 38). In 1958, a short-lived SPD-FDP government passed a law on the administration of schools (Reference DüdingDüding, 2008, 398). The law did not question the parallel school system but specified that representatives of the churches should only have an advisory function on the school boards (Reference FälkerFälker, 1984, 114f). Other education policy measures of the first SPD-FDP government were investments in school buildings and experiments with the introduction of a ninth grade at the Volksschule (Reference DüdingDüding, 2008, 398).

In 1953, the Ministry of the Interior and the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the federal states put in place an unsalaried advisory body, the German Committee for the Education and School System (Deutscher Ausschuss für das Erziehungs- und Bildungswesen), which was supposed to make suggestions for the development of the system. In 1959, this body published a recommendation called “framework plan for the remodeling and standardization of the general school system” (Rahmenplan zur Umgestaltung und Vereinheitlichung des allgemein bildenden Schulwesens), which marks a turning point in education policy discussions (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 166). As discussed in the next chapters, new conflicts were on the horizon.

Comparison: Setting the Scene for the Postwar Reform Period

In Germany, the political situation at the end of the Second World War is sometimes referred to as the Stunde Null (zero hour). The term implies that, at that moment, a new Germany was born: a democratic, stable nation that had little in common with its historical forerunners. In Norway, the immediate postwar period was also dominated by the motto that one would now be “building the country” to create a new and better nation. It is understandable that contemporaries had a need for such images, but of course nothing social is built up from scratch.

Quite to the contrary, postwar education politics were not a radical new beginning but embedded in long-term processes. In both countries, education reforms had been an element of state- and nation-building already during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This implied a gradual secularization of schooling, as the state took over responsibility and control from the church. In Norway, this process was not as conflictual as in Germany because the upper ranks of the Norwegian state church were integrated into the conservative national elites. In Germany, the Catholic Church stood in opposition to the Protestant Prussian state, especially in education politics. Many Catholics, not least in rural areas, identified with the Center Party and with denominational schooling. Political Catholicism was to some extent open to the social demands of the lower classes. Nevertheless, the state-church cleavage stood in the way of stable coalitions between Catholics, social democrats, and liberals. This conflict became foundational for German education politics.

In Norway, the early Liberal Party was highly influential, giving expression to center-periphery and rural-urban cleavages alike. It represented a broad movement of rural and urban outsiders belonging to the periphery, who stood in opposition to the conservative elites representing the political, cultural, and geographical center. This opposition came to expression in the language struggle, which was staged not least in schools. It also contained a conflict between ideas of ascription and achievement (Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan, 1999, 288ff). Norwegian liberals introduced the five-year comprehensive primary school in 1896. In addition, they supported modern instead of classical secondary education and created the modern lower-secondary school in 1896. They saw educational expansion and prolonged comprehensive schooling as means to create an enlightened, united citizenry and aimed at reducing social, economic, and geographical inequality. Many primary schoolteachers were involved in the liberal movement. The fact that Latin almost disappeared from the curriculum of the secondary schools in 1896 illustrates that conservative urban elites had weak influence on school reform processes even at that early stage. The Norwegian women’s movement of the nineteenth century was also well-connected to the liberal movement and had achieved full access to secondary education for girls already in 1882.

In nineteenth-century Prussia, debates over comprehensive schooling took place too, and social liberals and primary schoolteachers were the main bearers of reform ideas. A connection of all school types in a ladder system was demanded during reform-oriented times. However, in contrast with Norway, there was no equally strong peripheral, agrarian, liberal movement. The center-periphery and rural-urban cleavages were largely superposed by state-church and class cleavages. Liberalism was comparatively less radical, and nationalist liberals sided with the conservative state elites rather than with the growing working class (Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan, 1999, 289). As a result, the conservative supporters of classical elite education were more influential than in Norway. Primary schooling was expanded but remained far removed from secondary schooling for the privileged few, which was connected to the state bureaucracy. Even though school types with modern curricula developed, they did not become a link between these two worlds of education. The liberal supporters of modern education only achieved placing modern and classical secondary schools on a par with each other in 1900. Liberal and Catholic women founded private educational institutions for girls during the nineteenth century, but girls first received access to public secondary education in 1908, and in 1923 without restrictions. Nevertheless, nineteenth-century Norway and Prussia both had rather open secondary schools in terms of students’ social background, and some educational expansion took place during the nineteenth century (Reference Herrlitz, Hopf and TitzeHerrlitz et al., 2009, 251ff; Reference Nath, Apel, Kemnitz and SandfuchsNath, 2001; Reference TitzeTitze, 2004; Reference WiborgWiborg, 2009, 64ff).

The class cleavage gradually became highly salient in both cases, and social democracy became an important political player. The political left was highly split in both countries during the 1920s, but communist-socialist divisions were historically more significant in Germany and weakened the left considerably. For social democrats, the most important aim in education politics was to give working-class children access to better and longer education. Many social democrats became supporters of comprehensive schooling and joined forces with the liberals in this respect. As a result, the seven-year comprehensive primary school was introduced in Norway in 1920, when the Labor Party representative, Gjøstein, managed to convince parliament not to finance secondary schools that started earlier than in the eighth grade. In the newly founded Weimar Republic, the four-year comprehensive primary school was introduced in the same year. The reform succeeded because social democrats, liberals, and Catholics managed to cooperate, and this illustrates that attempts at comprehensivization were not necessarily doomed to fail in Germany.