The politics of education shape the lives of millions of schoolchildren, teachers, and families all over the world. They are related to the quality of a country’s democracy, to the character of its welfare state regime, and to the structure and development of the economy. Yet, comparative-historical knowledge about why school systems developed differently in different places remains limited. This holds especially for primary and lower-secondary education – possibly the most relevant and formative parts of the education system (Moe/Wiborg, 2016b, 11).

This book thus sheds light on an under-researched field. It provides a comparative-historical analysis of comprehensive school reform processes in Norway and Germany and proposes a Rokkanian theoretical framework to make sense of the conflicts and compromises that have shaped such reforms. By doing so, it explores the roots of a major difference between Nordic and continental school systems: their unequal degree of comprehensiveness. The term comprehensiveness refers to the extent to which all students of an age cohort attend the same educational institutions, independent of their abilities or social background. The more comprehensive a school system is, the less separation of students by means of parallel schooling, tracking, or ability grouping takes place. Because school systems always differentiate between students somehow, it makes sense to see comprehensiveness as a continuum, with the most comprehensive systems differentiating late and little and the least comprehensive systems differentiating early and in multiple ways. The opposite of comprehensiveness is segmentation, “the division of educational systems into parallel segments or ‘tracks,’ which differ both in their curriculum and in the social origins of their pupils,” as defined by Reference Ringer, Müller, Ringer and SimonRinger (1987, 7; Reference Ringer1979). The degree of comprehensiveness is related to systems of evaluation. Grades are often used for selection to parallel schools, tracks, or ability groups, while more comprehensive systems require less grading in primary and lower-secondary schools. Another criterion for the degree of comprehensiveness is the age of first selection of students to parallel schools or tracks (Figure 1.1). From sociological and educationalist research, we know that earlier selection increases the reproduction of social inequality (OECD, 2010a, 35f). However, we know little about why school systems’ comprehensiveness varies so greatly among developed countries.

The Nordic countries have been forerunners with regard to comprehensivization of their school systems. Over time, highly comprehensive school systems were formed in which children of all backgrounds attend primary and lower-secondary schools together until they are sixteen years old (Reference WiborgWiborg, 2009). Norway was the first country to introduce five years of comprehensive education in 1896 and seven years in 1920. During the 1950s to 1970s, comprehensive schooling was prolonged to nine years with the introduction of the youth school (ungdomsskole). This lower-secondary school type replaced two former parallel school types, the middle school (realskole) and the continuation school (framhaldsskole) (see Figures 1.2 and 1.3). The realskole was academically oriented and led to upper-secondary schooling and then potentially to university. The framhaldsskole was more vocationally oriented but did not award any formal qualifications.

Figure 1.2 The Norwegian general public school system in 1954

Figure 1.3 The Norwegian general public school system in 1979

The youth school initially consisted of two tracks, which resembled these older school types. Gradually, tracking was replaced with more flexible ability grouping and finally with mixed-ability classes. The reform was connected to the introduction of nine years of obligatory schooling and to the abolition of grades in the first six years, which were called children’s school. The Norwegian Labor Party also wanted to abolish grades in the youth school, but this proposal incited much opposition and failed. In the 1990s, the school enrolment age was lowered by one year, prolonging comprehensive education further. The Norwegian school system today provides ten years of comprehensive and obligatory schooling in the seven-year children’s school (barneskole), followed by the three-year youth school (ungdomsskole). Tracking sets in at the upper-secondary level.

In the continental welfare states, selection and separation continue to be exercised earlier in children’s life courses.Footnote 1 The German school system is among the least comprehensive. In 1920, four years of comprehensive primary schooling was introduced in the Weimar Republic. In the 1950s, the comprehensive primary school (Grundschule) still made up the lower stage of the so-called people’s school (Volksschule). The majority of students continued to the upper stage of the Volksschule and then to vocational training or the labor market. Only a minority received secondary schooling either in a middle school (Realschule) or in the prestigious academic secondary school, the Gymnasium. In the 1960s, the number of Realschulen and Gymnasien was increased in many West German federal states, including the largest federal state of North Rhine–Westphalia (NRW). In addition, a new school type was introduced: the integrated comprehensive school (Integrierte Gesamtschule). Despite its name and the intentions of reformers, it was not comprehensive because the other school types were not abolished. The primary school was separated from the upper stage of the Volksschule, which was turned into an independent lower-secondary school type, the Hauptschule. Nine, and later ten, years of obligatory schooling were introduced (see Figures 1.4 and 1.5). During the late 1970s, the social democratic–liberal government coalition of NRW suggested the introduction of a so-called cooperative school, meant to be a combination of the three traditional school types as tracks under one roof. In 1978, this reform was stopped by an alliance of reform antagonists, who collected over 3.6 million signatures. Today, most federal states in Germany still separate students to hierarchically ordered secondary school types at age ten.Footnote 2 Grading is usually introduced at the end of the second grade of primary school.

Figure 1.4 The North Rhine–Westphalian general public school system in 1954

Figure 1.5 The North Rhine–Westphalian general public school system in 1979

This book analyzes the political processes behind these school reforms comparatively and historically. Chapter 2 provides an overview of the development of the Norwegian and the German school systems up to the 1950s. The book then proceeds to analyze in detail the period from around 1954 to 1979. During this period, educational expansion reached an unprecedented peak all over the world, as increasing numbers of youths stayed on in the school system after having completed obligatory schooling (Reference Meyer, Ramirez, Rubinson and Boli-BennettMeyer et al., 1977). In Western Germany, it was the last period when the creation of a ten-year comprehensive school system briefly seemed possible, at least in the eyes of social democratic and liberal reformers. In Norway, as in many other countries, the period also saw “detracking” reforms that were more far-reaching than anything attempted later (Reference ÖstermanÖsterman, 2017a). The period was a critical juncture that shaped school systems until the present day. In Norway, comprehensive schooling until age sixteen became an almost self-evident feature of society, while it was never introduced in Germany but remained a highly contested issue.

The question this book tries to answer is why the paths chosen in education politics during this period were so different in these two cases. Why was the abolition of parallel schooling, tracking, ability grouping, and grading effectively carried out in Norway, while comparable reforms attempted in West Germany during the same period remained limited in scope? Why were the reforms strongly contested in Germany but not in Norway? The book provides historically and case specific answers to these questions but also tries to develop our general understanding of cleavage structures and cross-interest coalition-making in education politics.

The main argument of the book is that the differences in historical school development should be attributed to how cleavage structures, in the Rokkanian sense, facilitated or hampered cross-interest coalitions. The rural and religious population, many primary schoolteachers, and sections of the women’s movement were integrated into different kinds of coalitions in education politics: a coalition of social democrats and center parties in the Norwegian case and a Christian conservative coalition in the German case. The book thus advocates Rokkanian cleavage theory as a fruitful theoretical lens for comparative-historical analyses of education politics. Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan’s (1999) work provides a multidimensional and historically grounded perspective on political agency and coalition-making that is well worth returning to.

In the following, I first give an overview of the comparative literature on education politics and comprehensive school reforms. In the next section, the theoretical framework of this book is laid out. To this end, I introduce Rokkanian cleavage theory as well as another major perspective often applied in comparative political sociology, power resources theory. I then present the main argument and structure of the book. This introductory chapter ends with a note on the book’s history, including a reflection on case selection and methodology.

The Literature

Most comparative research in the field of education has focused on the distributional effects of education systems rather than on how reforms have come about.Footnote 3 There are good reasons for this. Inequality of educational opportunity and outcomes is an important topic. However, the lack of comparative analyses of education politics is a problem.

Consider, for example, the German case: For decades, German sociologists of education and educationalists have been almost obsessed with studying the reproduction of inequality in the German education system.Footnote 4 Much research shows that sorting students into parallel schools at the age of ten (re)creates strong social inequalities (Reference Maaz, Baumert, Cortina, Cortina, Baumert, Leschinsky, Mayer and TrommerMaaz et al., 2008, 242f). Variation in learning outcomes between schools is high in Germany because the different secondary school types have such unequal curricula and student bodies (OECD, 2016, 226). In contrast, Norway has fared comparatively well in international comparisons of the equity of education systems (OECD, 1972, 2005, 2010a, 2010b, 2016). Its comprehensive school system comprises fewer points of transition. Variation in students’ performance is lower than in Germany and almost all of this variation is within-school variation (OECD, 2016, 226).

These research findings have made little difference for German education politics. Researchers’ conclusion that early selection in the German system is conducive to the reproduction of inequality has not led to comprehensive school reforms. On the contrary, the multi-tier school system has persisted. German politicians and representatives of teachers’ organizations regularly express their desire for equality of opportunity, but few of them support far-reaching comprehensive school reforms. Why is this so? This question has received little scholarly attention. In consequence, we know a lot about the reproduction of inequality in the German education system but little about why the system’s presumably most inequality-enhancing feature – selection and parallel schooling from the age of ten – has never been successfully reformed.

A few studies do try to tackle the question of why comprehensive school reforms were successfully implemented in some places but not in others. Reference BaldiBaldi (2012), in his comparison of postwar education policy discourses in Britain and Germany, points out that German academics were slow in revising their ideas about ability, which he attributes to ideational and structural legacies from the Nazi era. An earlier, similar contribution is Reference HeidenheimerHeidenheimer’s (1974) work, in which he tries to explain the “different outcomes of school comprehensivization attempts in Sweden and West Germany.” He gives examples of more elitist attitudes prevalent among German experts on pedagogy, teachers, politicians, and parents. He also compares the role of teachers’ associations and finds that the German Gymnasium teachers had greater influence than their Swedish counterparts. This is attributed to the fact that they were part of a strong anti-reform coalition with the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), conservative bureaucrats, and middle-class parents’ associations. Reference HeidenheimerHeidenheimer (1974) concludes that the German left was not united enough to overcome this challenge and points to internal conflicts. In Sweden, no party ever declared itself clearly against comprehensive reform and the Swedish secondary schoolteachers were left on the sidelines politically. Both Reference BaldiBaldi (2012) and Reference HeidenheimerHeidenheimer (1974) point out important ideological differences. However, they do not provide an explanation for why conservative ideas on schooling remained so powerful for so long in Germany, even among lower- and middle-class groups who could have profited from comprehensive school reforms.

Another argument that has been brought forward to explain the German case is that the federalist structure is conducive to the institutional stickiness of the school system (Reference BaldiBaldi, 2012; Reference Ertl and PhilippsErtl/Philipps, 2000; Reference HahnHahn, 1998). Federalism can be considered to produce veto points in the decision-making process because it creates an additional institutional level on which reforms must be negotiated (Reference Huber and StephensHuber/Stephens, 2001; Reference Immergut, Steinmo, Thelen and LongstrethImmergut, 1992). However, a study by Reference ErkErk (2003) indicates that German federalism tends to develop unitary characteristics in education and that standardization is high despite federalism. Moreover, the present book focuses on one federal state, NRW. In theory, North Rhine–Westphalian school politicians could have introduced comprehensive lower-secondary schooling even though other federal states did not. This would have been legally possible because school policy falls under the responsibility of federal state governments. It would potentially have entailed conflicts in the bodies in which federal states’ school policies are coordinated. This possibility of conflict with other federal states, however, played no significant role in the reform debates in NRW, as demonstrated in the empirical chapters of this book.

The most important comparative contribution so far is the work of Reference WiborgWiborg (2009, Reference Wiborg2010), which focuses on the history of comprehensive schooling in Scandinavia, Germany, and England. Wiborg’s findings are that (1) intensive processes of state-building were related to education reforms but cannot explain why the level of vertical differentiation differs so strongly between Scandinavia and Germany (Reference WiborgWiborg, 2009, 47). She demonstrates further that (2) “the relative homogeneity of Scandinavian societies was propitious for the development of a ladder system of education” from the nineteenth century onward but that the difference in class structures cannot account entirely for the lack of a similar development in Prussia (Reference WiborgWiborg, 2009, 215). She emphasizes (3) the importance of liberal parties in the creation of comprehensive education in Scandinavia, through the introduction of comprehensive primary schools and middle schools, which were – in theory – open to all (Reference WiborgWiborg, 2009, 75ff; Reference Wiborg2010, 546ff). Reference WiborgWiborg’s (2009, 231; Reference Wiborg2010) final hypothesis is that (4) “it was ultimately the nature and strength of social democracy that explains the divergent development of comprehensive education in Scandinavia, on one hand, and Germany and England, on the other.” In Scandinavia, social democratic parties forged alliances with the liberal peasantry and later with the emerging white-collar middle class, which allowed them to introduce ten years of comprehensive education. German and English social democracy did not manage to build similarly strong alliances.

These are convincing findings. Wiborg’s historical account is highly sophisticated and useful. However, her claim that German postwar social democrats were ideologically “rooted in the past” and therefore did not manage to convince middle-class voters is not supported by the empirical analysis in the present book (Reference SassSass, 2015; Reference WiborgWiborg, 2010, 554). German social democrats were ideologically less radical than Norwegian social democrats, but they were deeply split. Some leading figures in the party never supported comprehensive schooling wholeheartedly. Furthermore, the different roles played by conservatives and Christian democrats in Norway and Germany and the salience of crosscutting cleavages are important factors for the political outcomes, as shown in this book.

Several comparative doctoral theses have focused on aspects of comprehensive “detracking” reforms (Reference HaberstrohHaberstroh, 2016; Reference ÖstermanÖsterman, 2017b). Reference ÖstermanÖsterman (2017a, 157f) demonstrates that the age of first selection was reformed in many countries during the 1960s and 1970s and has remained rather stable since then. Based on a quantitative analysis of this development in thirty-one developed countries, he concludes, “social democrats are clearly more likely to carry through detracking reforms than any of the other major parties” (Reference ÖstermanÖsterman, 2017a, 168). Dominance of Christian democratic governments “is related to heavier tracking through early selection,” while the role of conservatives and liberals remains unclear in his results (Reference ÖstermanÖsterman, 2017a, 171). As he points out, “detailed case studies” are needed to understand “how political coalitions are formed around tracking reforms” (Reference ÖstermanÖsterman, 2017a, 172). His main finding that social democrats have been protagonists of comprehensive school reforms, while Christian democrats have opposed such reforms, is valid for many cases. However, one should be careful in concluding that Christian democrats always oppose comprehensive school reforms. In the present book, it is shown that the small Norwegian Christian democratic party (the Christian Democrats) did not. In fact, the Norwegian minister of education who finalized the introduction of the youth school in 1969 was a Christian democrat, Kjell Bondevik.

One of the newest contributions to the field is Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann and NeimannsBusemeyer et al.’s (2020) study of public opinion and education reform in Western Europe, in which the authors demonstrate, among other things, that public support of comprehensive schooling seems to be high in all their cases. Even in Germany, 84 percent of the study’s respondents agree that “all children, regardless of their social background, should be taught in the same schools so that everyone can learn from each other,” while only 28 percent agree that “children with different social backgrounds should be taught in different schools in order to provide more targeted support.”Footnote 5 They also find that voters for left-wing parties are more supportive of comprehensive schooling and that voters for right-wing parties, wealthier, and more highly educated respondents, but also the respondents belonging to the poorest quintile, are more skeptical (Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann and NeimannsBusemeyer et al., 2020, 135ff).

Besides these few studies, not much comparative work is concerned with the history and politics of comprehensive education. Reference Hörner, Döbert, Reuter and BothoHörner et al. (2015) provide a useful overview of European education systems, but without analyzing the differences in the politics of comprehensive schooling in detail. Classic studies like those by Reference RingerRinger (1979), Reference Müller, Ringer and SimonMüller et al. (1987), Reference ArcherArcher (2013 [1979]), or Reference GreenGreen (2013 [1990]) help us to understand the formative periods of education systems and have laid the foundations for the field but are less explanatory regarding development after the Second World War. There are many excellent historical and sociological single case studies, which are useful also as secondary sources for comparisons but which do not provide explanations for the diverging development in different countries.Footnote 6 A range of studies have analyzed education politics in OECD nations comparatively, but with a focus on upper-secondary schooling, vocational schooling, higher education, education spending, or teachers unions (Reference BusemeyerBusemeyer, 2007, Reference Busemeyer2014; Reference GarritzmannGarritzmann, 2016; Reference Schmidt and CastlesSchmidt, 2007; Reference ThelenThelen, 2004, to name a few). Some studies of the politics of vocational and higher education, such as Reference BusemeyerBusemeyer (2014), rightly emphasize the role of Christian democratic parties for the development of the continental education systems, but without spelling out the implications for primary and lower-secondary schooling.

In a contribution on teachers’ unions and education systems around the world edited by Reference Wiborg, Moe and WiborgTerry M. Moe and Susanne Wiborg (2017a), Reference Wiborg, Moe and WiborgMoe and Wiborg (2017b) point out that focusing on teachers’ unions is a good entry point for comparative analysis because such unions have been key players almost everywhere. This is certainly the case in Norway and Germany (Reference Nikolai, Briken, Niemann, Moe and WiborgNikolai et al., 2017; Reference Wiborg, Moe and WiborgWiborg, 2017). The present book adds to these analyses by providing a theoretical explanation for why upper-secondary schoolteachers were more successful politically in Germany than in Scandinavia. The book includes organizations of lower-secondary and primary schoolteachers with Christian roots in the analysis of the German case. These have often been ignored even though they have played important roles. Splits between social democratic and Christian teachers are at the root of German primary schoolteachers’ comparable lack of influence.

Several authors have advocated including education politics to a higher degree in comparative welfare state analysis, because the education-political paths of Western nation states coincide with typologies of welfare state regimes based on other policy fields (Reference Iversen and StephensIversen/Stephens, 2008; Reference West and NikolaiWest/Nikolai, 2013; Reference Willemse and de BeerWillemse/de Beer, 2012). One attempt at this has been made by studies of party preferences in education politics based on data from the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP)Footnote 7 (Reference AnsellAnsell, 2010; Reference Busemeyer, Franzmann and GarritzmannBusemeyer et al., 2013). This dataset provides quantitative information on party manifestos over time and includes a variable dubbed “educational expansion.” This variable does not distinguish between policies but includes almost all statements on education, no matter what their exact content is.Footnote 8 Furthermore, Reference AnsellAnsell (2010) and Reference JakobiJakobi (2011) have employed the CMP data only on an aggregated level in their analyses. As pointed out by Reference Busemeyer, Franzmann and GarritzmannBusemeyer et al. (2013, 526), “country contexts and policy legacies […] play a crucial role in shaping the political competition over educational expansion,” which entails that studies based exclusively on aggregated data might “blend […] over major variation on a less aggregated data level (i.e. the country level) as well as changes across time.” For example, Reference JakobiJakobi’s (2011) finding that educational expansion is today supported by all mainstream parties, and should be considered a consensual issue, can only be upheld if one does not differentiate between the suggested educational policies, which can vary immensely. As demonstrated for example by Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann and NeimannsBusemeyer et al. (2020), heated debates about the age of first selection, ability grouping, school choice, or private schooling still characterize education politics in many places.

One can conclude that both variable- and case-oriented studies will be necessary for the further development of the research field. There is a particular lack of case-oriented, comparative-historical studies that take the historical, political, and institutional environment of political actors into account in analyses of the politics of education. The present book is a step in this direction. It informs current scholarly and education policy debates by shedding light on how coalitions and conflicts in education politics come about.

Theoretical Framework

The empirical analysis in this book is guided by two classic theoretical perspectives: power resources theory and Rokkanian cleavage theory. While both approaches are useful for the analysis of the politics of education, this book demonstrates that education politics are shaped by more than class conflict and material interests, so the focus of power resources theory is somewhat too narrow.Footnote 9 Rokkanian cleavage theory provides a more nuanced understanding of how cross-interest coalitions come about. In the following, both approaches are discussed.

Power Resources Theory

Power resources theory was developed by Walter Korpi (Reference Korpi1974, Reference Korpi1978, Reference Korpi1983, Reference Korpi1985), John D. Reference StephensStephens (1979), and Gøsta Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1985, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). In short, they argue that different forms of welfare state development result from the distribution of power resources between socioeconomic classes and class fractions. They also look at cross-class coalitions to explain the outcomes of social struggles. A central assumption is that “employers and other interest groups that control major economic resources are likely to prefer to situate distributive processes in the context of markets, where economic assets constitute strategic resources and […] tend to outflank labor power” (Reference KorpiKorpi, 2006, 173). In response, those who have no large amounts of capital at their disposal need to organize in parties and unions, which have sought to remove some activities from the market to achieve social citizenship and decommodification (Reference Esping-AndersenEsping-Andersen, 1990, 35ff; Reference KorpiKorpi, 2006).

Traditionally, this strand of literature has not paid much attention to the education system. However, the concept of social citizenship was first defined by T. H. Reference MarshallMarshall (1950, 11) as “the whole range from the right to a modicum of economic welfare and security to the right to share to the full in the social heritage and to live the life of a civilized being according to the standards prevailing in the society.” Reference MarshallMarshall (1950, 11, 25f) held that “[t]he institutions most closely connected with [social citizenship] are the educational system and the social services” and argued that the first step toward the establishment of social rights in the twentieth century was the expansion of public elementary education in the nineteenth century. In line with Marshall’s thinking, the post–Second World War educational expansion and reforms can be considered an extension of social citizenship.

Power resources theory is an actor- and conflict-oriented theory. Reference KorpiKorpi (2006) provides a useful conceptualization of different kinds of actors. Protagonists are defined by Reference KorpiKorpi (2006, 182) as “agenda setters” in the extension of “social citizenship rights.” Consenters are actors who either decide to switch from opposition to consent “for fear of voter reactions” or “attempt to modify policies to accord with their second-best or even lower levels of policy preferences and, if successful, can consent to a revised proposal” (Reference KorpiKorpi, 2006, 182). In other words, consenters are willing to compromise. Antagonists are actors who oppose a policy throughout the policy-making process. It is important to remember that protagonists of one policy, for example comprehensive schooling, may be consenters, or even antagonists, as far as another policy is concerned, for example decentralized countryside schooling.

To understand why some actors are more successful than others in asserting their political program it is helpful to consider the distribution of power resources between them. Reference KorpiKorpi (1985, 33) defines power resources “as the attributes (capacities or means) of actors (individuals or collectivities), which enable them to reward or to punish other actors.” This means that power resources are defined in a relational way and are relevant even when not activated. Reference KorpiKorpi (1985) also holds that indirect power strategies help managers of power resources avoid the mobilization and application of their resources, which would incur costs and increase uncertainty. One such strategy would be the attempt to influence the creation and shape of institutions. Institutions are conceptualized by Reference KorpiKorpi (1985, 38) as “residues of previous activations of power resources, often in the context of manifest conflicts which for the time being have been settled through various types of compromises.”Footnote 10 Another strategy discussed by Korpi is the attempt to influence ideologies and beliefs of other actors. Reference KorpiKorpi (1985, 34) speaks of normative power resources, which have lower costs than coercive power resources: “Attempts to develop and to spread ideologies and to cultivate legitimacy can be regarded as conversion techniques for decreasing the costs of power” (Reference KorpiKorpi, 1985, 39). The present book analyzes power resources and ideologies of collective actors in conflicts in education politics. It examines their internal ideological unity as well as the question of which ideological arguments became hegemonic in the two cases.Footnote 11

In power resources theory, it is assumed that collective actors such as parties “perform the crucial mediating role” with respect to the political articulation of class interests (Reference Huber and StephensHuber/Stephens, 2001, 17). Reference KorpiKorpi (2006, 174) defines class as “categories of individuals who share relatively similar positions, or situations, in labor markets and in employment relations.” He contends that it is an empirical question to what extent categories of similarly placed individuals organize themselves through collective action or develop group identification. However, as Reference KorpiKorpi (2006, 173) points out,

Socioeconomic class constitutes [only] one of the multiple lines of potential cleavages (including such others as religion, ethnicity, occupation, and economic sectors) around which collective action […] can be mobilized. The extent to which crosscutting cleavages are mobilized is affected by structural factors, but distributive strife is also focused on influencing the relative importance of these competing lines of cleavages.

For this reason, it would be too simplistic to assume that collective actors, such as parties, always represent class interests in a clear way. They also must position themselves in relation to crosscutting cleavages. This can lead to internal splits or consolidate broad cross-interest alliances, depending on actors’ strategies in response to the cleavage structure. The key to understanding the development of welfare states lies in understanding what kind of cross-interest coalition existed in a country (Reference Esping-AndersenEsping-Andersen, 1990, 30). As demonstrated by Reference Esping-AndersenEsping-Andersen (1990), the coalition between the Scandinavian farmers and the labor movement was central in Scandinavia. The development of continental welfare states, such as Germany, is strongly related to the strength of Christian democratic parties and the Catholic Church (Reference Huber and StephensHuber/Stephens, 2001, 16ff; Reference Manow, Kees, Manow and van KersbergenManow/van Kersbergen, 2009). However, as pointed out by Reference Manow, Kees, Manow and van KersbergenManow and van Kersbergen (2009, 14ff), power resources theory does not provide a systematic explanation for why the middle classes sided with social democracy in some countries but with Christian democratic parties in others.

Rokkanian Cleavage Theory

Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinStein Rokkan’s (1999) cleavage theory can help us to develop a more nuanced understanding of how such political coalitions come about. Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan (1999, 276) holds that political conflicts can result from many interactions in a social structure, but only a few will lead to polarization and thereby to cleavages. Rokkan never defined the term cleavage. His understanding of the concept remains implicit and linked to grounded historical analyses. However, a close reading of his work reveals what the term refers to. In short, cleavages are long-standing, highly polarized political conflicts, or, in Reference Flora, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinFlora’s (1999, 7, 34–39) words, “fundamental oppositions within a territorial population” characterized by comparable importance and durability. Cleavages have structural, ideological, and organizational dimensions. They are composed of different “social constituencies,” “cultural distinctiveness,” and “organizational networks” (Reference BartoliniBartolini, 2000, 25; Reference Bartolini and MairBartolini/Mair, 1990, 212–249).

In the literature on cleavages, it is not always clear to what extent the term refers to constraining structures transmitted to us from the past or to changeable ideological and political configurations of today, constituted by political action. In this book, cleavages are seen as both, because they link structure and action over time. They have historical roots and represent constraints for the political, collective actors of today, in the sense that they have shaped institutions, identities, and ideologies – and thereby also have shaped the actors themselves. Yet, they only exist through action. In other words, they are continuously recreated in ongoing political conflicts and are therefore to some extent open for change (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and RokkanLipset/Rokkan, 1967, 6). In terms of the ideological expressions of cleavages, this means that while current social movements, parties, and organizations are ideologically linked to their forerunners, it is up to each generation to define political interests and thus the content of cleavages in new terms. As structural and material conditions change, actors strategically adapt their views, aims, and forms of organization, but not without reference to the long-standing oppositions which have formed their political identities and understandings. During critical junctures, actors’ decisions and strategies become particularly meaningful and can to some extent set the course for future events (Reference MjøsetMjøset, 2000, 392).

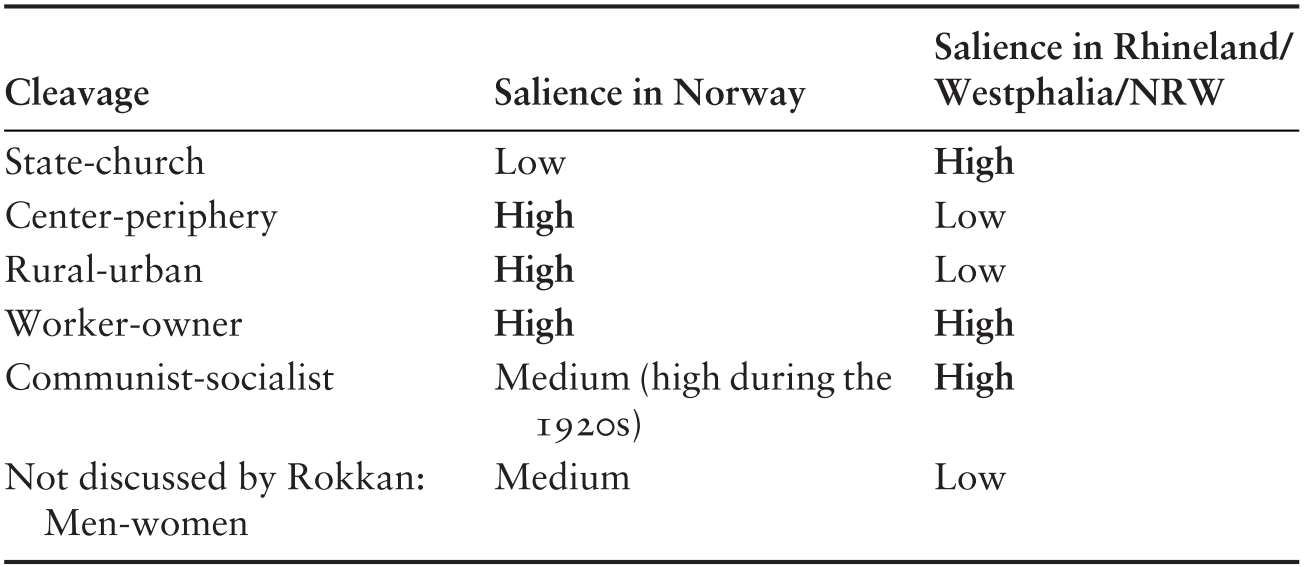

Cleavages can mutually reinforce, superpose onto, or cut across each other. They can vary in intensity, so that some become more salient than others. Cleavages should never be analyzed on their own since territorial areas are characterized by a set of interdependencies between cleavages (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and RokkanLipset/Rokkan, 1967; Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan, 1999, 309). Rokkan uses the term “cleavage structure” to describe a combination of cleavages characterizing an area’s social structure and political system (Reference Flora, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinFlora, 1999, 7, 34–35). He identifies several critical historical junctures that have resulted in cleavages and shaped political systems (Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan 1999, 303–319; Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Salience of cleavages in Norway and Rhineland/Westphalia/North Rhine–Westphalia up to the postwar reform period

Regarding the organizational articulation of cleavages, Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan (1999) pays most attention to political parties. In his writing, it becomes clear that parties can be based on several cleavages to varying degrees (Reference SassSass, 2020). Even if based primarily on one cleavage, they must position themselves in relation to other cleavages, which might be overlapping or crosscutting. Besides the electoral channel, Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan (1999, 261–273) points to the corporatist channel of decision-making as another form of articulation of cleavages. He discusses for example the role of unions, farmers’ and fishermen’s organizations, and employer organizations. Rokkanian cleavage theory should not be considered a theory pertaining to the party system only.

The oldest cleavages, in Rokkan’s view, are the center-periphery and the state-church cleavage. The center-periphery cleavage was especially salient in the Protestant North. In Norway, it came to expression in the establishment of the Liberal Party, which was a broad opposition movement of farmers, peripheral ethnic groups, and urban outsiders to urban elites, who organized themselves in the Conservative Party (Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan, 1999, 375; Reference Rokkan and Dahl1966). The state-church cleavage was less salient because Protestant state churches were integrated into nation-building processes. Dissenting groups of Protestant minorities were integrated into peripheral movements. Neither these dissenting groups nor the Protestant state churches fought the state’s attempts to control the education system (Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan, 1999, 286ff). In 1933, a small Christian democratic party (the Christian Democrats) was founded in Norway, representing rural Christian laymen, and from this point on the state-church cleavage became somewhat more salient.

The religiously mixed areas on the continent saw the rise of peripheral movements of Protestant dissidents and Catholic minorities. This led to the development of a dominant state-church cleavage and bitter conflicts, not least about education. In Germany, Catholics founded the ultramontane Center Party, which stood in opposition to the Protestant Prussian state. It was supported by Catholic workers and the Catholic middle classes and was strong in the provinces of Rhineland and Westphalia. The German Catholic movement comprised many organizations, including teachers’ unions. After the Second World War, the CDU followed in the Center Party’s footsteps and, while aiming to unite Protestants and Catholics, remained the main representative of Catholic interests in Germany (Reference SchmittSchmitt, 1989).

In addition, in Europe’s Protestant North, a rural-urban cleavage developed, dividing producers of primary goods in the countryside and the middle classes in the cities. In some cases, this led to the founding of agrarian parties. In Norway, the agrarian Center Party broke out of the periphery coalition within the Liberal Party in 1920 (Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan 1999, 375). In economies dominated by large-scale landed property, such as Prussia or the United Kingdom, agrarian interests were integrated into conservative alliances (Reference Flora, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinFlora, 1999, 40f). In religiously mixed areas, Catholic parties organized Catholic farmers and aggregated agrarian interests. Political Catholicism tended to superpose on the center-periphery and later the rural-urban cleavage (Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan, 1999, 309). The rural-urban cleavage within Rhineland and Westphalia was also not that salient, since these were densely populated, industrialized areas with only a few rural spots. As demonstrated in this book, rural interests were integrated into the CDU’s agenda.

The class cleavage between workers and capital owners became highly salient and led to the formation of labor parties almost everywhere, bringing European party systems closer to each other (Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan, 1999, 290). Labor movements were often characterized by splits based on conflicting ideas about nationhood and international solidarity. Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan (1999, 307, 334ff) concludes that this communist-socialist cleavage was greatest in countries where conflicts over national identity remained unsolved. The German labor movement was deeply split after 1918. Norway also had deep internal conflicts within the labor movement, at least during the 1920s, when the Norwegian Labor Party became radicalized.Footnote 12 In 1961, the Socialist People’s Party was founded in Norway, so internal splits of the labor movement remained relevant. In Germany, the Communist Party (KPD) was forbidden in 1956. A new Communist Party (DKP) was founded later but remained insignificant in terms of election results. The communist-socialist cleavage remained relatively salient in Germany due to the country’s separation into a communist East and a capitalist West. The labor movement was split into an anti-communist, right-wing current and a current of radical, often younger leftist reformers.

One final cleavage has not been theorized by Rokkan: the gender cleavage. Gender is a politically divisive issue of significant importance and durability that should be included in a modernized theory and analysis of cleavage structures (Reference Sass and KuhnleSass/Kuhnle, 2022). Structurally, the gender cleavage was and remains to some extent based in women’s legal, political, social, and economic subjugation. Ideologically, it has been expressed by narratives legitimizing this subjugation and by the development of counter-identities and demands by women activists and their male sympathizers. Finally, it has been politically articulated by organizations of the women’s movement, including organizations of female teachers, and by their opponents. These opponents were often conservatives but could be found among liberals, social democrats, or unionists, illustrating the crosscutting nature of this cleavage.Footnote 13

The historical origin of the gender cleavage should be dated to the first wave of the organized women’s movement, which took place roughly from the last decades of the nineteenth to the first decades of the twentieth century. It became less salient during the 1930s to 1950s but gained salience again during the second wave of women’s political mobilization, from around the 1960s to the 1980s. As Reference TherbornTherborn (2004, 71f) points out, “[t]he further south and east one ventured from northwest Europe, including within Europe itself, the more rigid were the patriarchal rules one would find.” In Scandinavia, women’s rights were enforced significantly earlier than in the rest of Europe and women’s movements were comparatively more influential and united (Reference TherbornTherborn, 2004, 79ff). The Protestant state churches in Scandinavia accepted the state’s right to regulate family matters, which was not the case with the Catholic Church (Reference TherbornTherborn, 2004, 78). As demonstrated in Chapter 5, the gender cleavage played a role in education politics, even though it was not among the most salient cleavages. It was comparatively more salient in Norway.

The Politics of Comprehensive School Reforms: Reflections and Expectations

In this book, power resources theory and Rokkanian cleavage theory provide the main frames of reference. These theories are not so much opposed to each other; rather, the Rokkanian perspective represents a widening of focus. While power resources theory has concentrated primarily on the class cleavage and has considered cross-class coalitions in relation to this, Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan (1999) directs our attention to the importance of additional cleavages. Some final remarks are necessary on how these theoretical perspectives can guide the analysis of education politics and comprehensive school reforms. What do they lead one to expect and to look for in the empirical cases? To get a clearer idea of this, it is necessary to reflect on how the school as an institution, and its reforms, can be conceptualized based on these two perspectives.

From a power resources perspective, the current school system is the result of previous class conflicts and cross-class coalitions. The working class has long been excluded from secondary and tertiary education. Against this background, comprehensive schooling can be considered a tool for the extension of social citizenship and decommodification, as it implies that students of all classes are taught together with the declared aim to give them equal access to a longer education and to foster solidarity. For this reason, power resources theory would lead one to expect that the social democratic parties of the postwar decades embraced and supported comprehensive school reforms, while their opponents on the political right opposed them. The success or failure of such reform attempts could then be attributed to the distribution of power resources between the left and the right or between reform protagonists and antagonists. Power resources theory also suggests that it is important to examine the role of consenters and the coalition-making between potential consenters, protagonists, and antagonists.

From a Rokkanian perspective, the school as an institution is also a residue of historical conflicts. However, these conflicts involve numerous collective actors, whose oppositions are not exclusively based on class relations or economic interests. For example, as Reference Rokkan, Kuhnle, Flora and UrwinRokkan (1999) points out repeatedly, the education system was originally controlled by the Church. As the central state gradually took over more responsibility, this entailed state-church conflicts but also conflicts over peripheral territorial identities, language, or centralization. Even though the class cleavage was highly salient during the postwar reform period, state-church, center-periphery, rural-urban, communist-socialist, and gender cleavages also continued to come to expression in education politics. The school mirrored all social relations, and its development was therefore of interest to many. Rokkanian cleavage theory thus leads one to expect that reforms of the school system were a result of complex interactions between a range of actors who had to strategically navigate cleavages to build stable coalitions.

Both perspectives suggest that it is important to analyze actors’ power resources and position with respect to the class cleavage. Both traditions also emphasize the relevance of coalition-making. However, Rokkanian cleavage theory points toward coalitions that are not only cross-class but cross-interest coalitions based on the entire cleavage structure. For the case analysis, this implies that one should look for interactions between class conflict and other oppositions in education politics. In this book, this is done by examining not only comprehensive school reforms but also other major school reforms and debates of the time.

A crucial question then becomes, to what extent different packages of reform represented compromises between different social groups that served to integrate them into pro- or anti-reform coalitions. The extension of comprehensive schooling implied that not only working-class youths but also some middle-class youths, especially those with rural backgrounds, and girls would receive a longer education than had been usual before. In this sense, these groups benefitted from the reforms. Some form of cross-interest pro-reform coalition between the rural population, farmers, the women’s movement, and social democracy should therefore be considered a historical possibility.

On the other hand, we must consider that these same groups possibly had other concerns, based on other cleavages, which might have been more important to them than access to secondary schooling for their offspring. For example, it is possible that they wanted to strengthen Christian education and private schooling or demanded a pushback against what they considered excessive centralization, wrong language politics, or communist ideology in the schools. It is also possible that they considered a prolongation of obligatory schooling and an increase in secondary schools sufficient and saw no urgent need for comprehensive schooling. All this could have created opportunities both for comprehensive school reform protagonists and antagonists to build coalitions around these or similar issues. To what extent this happened in different cases is an empirical question that should be answered by examining political conflicts with an open mind.

To sum up, the cleavage structure can also be considered an opportunity structure for political actors of the left and the right. By designing policy packages and compromises that cater to the interests and ideologies of different social groups, actors can try to mobilize support based on several cleavages at the same time. Actors who do not manage to integrate different interests related to crosscutting cleavages might end up on the sidelines, ideologically and organizationally divided and comparatively powerless. The cleavage structure does not predetermine the outcomes of such attempts at coalition-making, as different kinds of compromises remain historically possible, but it can facilitate or hamper specific coalitions.

The Argument and Structure of This Book

The main argument of this book is thus that coalitions, oppositions, and outcomes in education politics can only be understood in light of the cleavage structure as a whole because additional cleavages besides the class cleavage shape actors’ interests, ideologies, and inclinations for who they want to cooperate with – or not. Norwegian social democrats and German Christian democrats both managed to build successful coalitions in education politics by mobilizing support from several social groups based on additional cleavages besides the class cleavage. In the Norwegian case, social democrats managed to include peripheral, rural, and women’s interests in their comprehensive school reform packages. In the German case, Christian, especially Catholic, and rural interests were integrated by the CDU. In this process, relatively similar social groups turned into consenters to comprehensive schooling in the Norwegian case but into antagonists in the German case. Norwegian conservatives and German social democrats also attempted to build cross-interest coalitions with these groups but did so less successfully. The different cleavage structures were crucial for these historical outcomes.

The book arrives at this argument step by step. First, Chapter 2 gives an overview of the development of Norway’s and Germany’s school systems up to the 1950s, with the aim to set the scene for the analysis of the postwar reform period. The historical narrative focuses on comprehensive and other much-debated reforms of primary and secondary schooling. It shows how dominant cleavages came to expression in education politics over time and provides the necessary context to understand the conditions actors faced during the postwar period.

In Chapter 3, the political playing field of the postwar reform period is analyzed with a focus on the structural and organizational dimensions of cleavages. To shed light on the distribution of power resources, I compare election results, government participation, financial resources, and membership numbers of the main actors. Even though the Norwegian political left was somewhat more powerful, the differences in the distribution of power resources between the left and the right do not seem great enough to preclude a more similar political development in the two cases. The social base of the relevant political parties and teachers’ organizations is also examined. The analysis illustrates that many of the social groups organized by the Norwegian center parties, such as farmers, the rural population, and people with a strong Christian identity, including religious women, were found within the ranks of the CDU in Germany. Primary schoolteachers in Germany were divided into different organizations by denomination, while primary schoolteachers in Norway were more united. These findings can only be understood against the backdrop of the cleavage structures. The dominance of the state-church cleavage in Germany and of the center-periphery and rural-urban cleavages in Norway led to the development and consolidation of different party systems and organizational structures, in which rural and Christian interests were represented in different ways. In Norway, this meant that social democrats and conservatives had to build cross-interest coalitions with the parties of the political center. In Germany, social democrats and Christian democrats also competed for support from the Liberal Party, but from the point of view of the CDU, it was at least equally important to uphold its intra-party coalition of rural, Christian, and cross-class interests.

Chapter 4 examines how actors navigated these conditions in the conflicts over comprehensive schooling. It discusses chronologically how coalitions came about for or against the most significant comprehensive school reforms of the time. Chapter 4 focuses primarily on the ideological expressions of the class cleavage, and thus on how actors grouped into camps along a political left-right axis, into protagonists, consenters, and antagonists of these reforms. For the Norwegian case, it focuses on the youth school reform, including the failed abolition of grading in the youth school. For the North Rhine–Westphalian case, the conflicts over the introduction of the integrated comprehensive school and the attempted cooperative school reform are discussed.

The final section of Chapter 4 compares the two cases, concluding that conflicts over comprehensive schooling can be considered an expression of the class cleavage in both cases. However, there are differences regarding the hegemonic consensus and the coalitions which came about. The political right was ideologically more united in Germany, while the political left was more united in Norway. Comparatively radical and leftist arguments became hegemonic in Norway but not in Germany. Finally, the religious and rural population consented to the reforms in the Norwegian case and opposed them in the North Rhine–Westphalian case. While Norwegian primary schoolteachers for the most part supported the reforms, some of the German primary schoolteachers’ organizations at best consented to or even opposed comprehensive schooling.

How can we understand this outcome? How did Norwegian social democrats manage to build such a successful, hegemonic pro-reform coalition and why did German social democrats fail to do so? Or, to put it differently, what bound rural and Christian groups to the CDU and made them oppose comprehensive school reforms in Germany, while similar social groups in Norway became consenters to the reforms? To shed more light on these dynamics of coalition-making, Chapter 5 focuses on other struggles in education politics that influenced coalitions for and against comprehensive school reforms. These struggles were not ideological expressions of the class cleavage but of other cleavages.

In the first part of Chapter 5, struggles over religion are at the center of analysis. For the Norwegian case, debates about Christian education, Christian private schools, and the Christian preamble of the school law are analyzed. For NRW, the conflict over denominational schooling, which was related to the introduction of the Hauptschule as an independent lower-secondary school type, is discussed. The second part of the chapter focuses on struggles over the centralization of rural schooling. Such struggles took place in both cases but were fiercer in Norway. The third and fourth parts of the chapter focus on two country-specific conflicts, namely the Norwegian language struggle and West German anti-communism and the communist-socialist cleavage in German education politics. Neither of these conflicts have an equivalent in the other case but both have influenced the alliances between actors. The chapter then analyzes struggles related to gender, with a focus on debates about girls’ education and coeducation and on the role played by female teachers’ organizations. The last section discusses and compares how crosscutting cleavages contributed to a weakening or strengthening of comprehensive school reform alliances in the two cases.

Chapter 6 develops an overall conclusion. In the first part of the chapter, the main results of the comparative-historical case studies are summarized. It can be said that the Norwegian Labor Party compromised on several of the crosscutting school-political issues mentioned above, which made it difficult for the Conservative Party to build up a strong oppositional camp to comprehensive school reforms. The center-periphery cleavage and the rural-urban cleavage were the most salient and influential crosscutting cleavages. These cleavages coincided, which strengthened alliances between social democracy and the political center. For example, the center parties’ dislike of centralization meant that they were interested in providing rural communities with good local schools, which in many cases were so small that ability grouping or tracking would have been too costly. The state-church cleavage overlapped with the rural-urban and center-periphery cleavages and did not threaten the hegemony of social democracy. Christian education and private schooling were much-debated topics, but there was no agreement among the nonsocialist parties. The gender cleavage also split the four nonsocialist parties and thus strengthened the position of the Labor Party further. From the 1950s to the 1970s, social democratic reform ideas shaped Norwegian education politics to a large extent. This applied even during the center parties/conservative government of 1965 to 1971, which continued the social democratic youth school reform. Only from the 1970s onward was social democratic dominance somewhat weakened.

In NRW/Germany, the state-church cleavage and the communist-socialist cleavage especially weakened comprehensive school reform coalitions and a much more stable conservative antagonist alliance developed. The communist-socialist cleavage came to expression in splits within the German left. Anti-communist arguments against comprehensive schooling played a vital role for the internal unity of the antagonists’ camp. Rural-urban and center-periphery cleavages mostly overlapped with the dominant state-church cleavage, which came to expression in fierce debates about denominational schooling. The state-church cleavage crosscut the class cleavage and strengthened the internal alliance of the CDU, rather than offering the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) any means to weaken it. The gender cleavage remained somewhat latent beneath state-church and class cleavages and did not threaten the dominance of the CDU, which had the support of Catholic women’s and female teachers’ organizations. SPD and FDP managed to undermine the hegemony of the CDU in education politics for a short period from the mid-1960s to the early 1970s, during which they pushed through centralization reforms, reforms of denominational schooling, reforms of girls’ schooling, and the introduction of the integrated comprehensive school. During the mid-1970s Christian democratic ideological hegemony was restabilized.

The second and third part of the final chapter discuss some general conclusions that can be drawn from this work and open questions that would merit further research. Most importantly, the book demonstrates the fruitfulness of considering crosscutting cleavages. The analysis also shows that political parties can be founded on more than one cleavage and that several parties can give voice to the same cleavages. In addition, cleavage theory can help us to understand intra-party splits, because currents within parties are also related to parties’ positioning in the cleavage structure. With regard to future research on education politics, the Rokkanian approach could be useful for a wide array of research questions.

Finally, the concluding chapter discusses in brief how legacies of the postwar reform period influence the current situation in Norway and NRW/Germany and what similarities can be found in education politics between now and then. Even though the political playing fields and debates have changed, different cleavages still come to expression, with consequences for political coalition-making.

A Note on the Book’s History, Methodology, and Case Selection

This book is the result of a long period of intense comparative-historical and case-oriented research begun in 2012. The two cases were researched in depth, based on a wide array of primary sources including party manifestos, parliamentary documents, documents of teachers’ organizations, and twenty-three expert interviews with people who have been active in education politics during the postwar reform period (see Annex for lists of the studied manifestos, parliamentary documents, and biographical introductions of the interviewed experts).Footnote 14 The book also builds on a wealth of secondary sources, such as single case studies of Norway and Germany.Footnote 15 Triangulation of data served to crosscheck validity and reliability of the book’s sources. For example, memory lapses and factual errors in the interviews could be identified by studying parliamentary documents, while the interviews provided insights into the political processes that were not necessarily available in the written sources.

However, the origin of this book should be dated further back in time to my personal experience as a German student and later as university student in Norway. Why, I wondered, had my home country never introduced comprehensive education beyond the age of ten, while the Scandinavian countries, which at first glance seemed culturally not so dissimilar, had taken a different route? I found it intriguing how much Scandinavian and German perspectives on schooling differed. My intuition that a systematic comparison could help me to understand these differences eventually became the motivation to embark on this work. A few more words on my case selection are necessary.

In some strands of political science, choosing one’s cases because they seem interesting and intrinsically relevant is not considered a wise choice. Rather, one is required to choose one’s cases based on assumptions, proclaiming for example that they are “most similar,”Footnote 16 meaning that they are as similar as possible except for the occurrence of the phenomenon to be explained – in this case, comprehensive schooling. It is possible to argue that Norway and Germany make up most-similar cases. Both have electoral systems based on proportional representation, there is institutionalized vocational education, and tertiary education is free. Public education has been comparatively dominant both in Norway and in Germany (OECD, 2010a, 2010b, 2012). Before the postwar reforms, historical similarities of the two school systems were mirrored in the terms used for different school types (Norwegian: folkeskole/realskole/gymnas, German: Volksschule/Realschule/Gymnasium). During the 1960s and 1970s, a spirit for reform made itself felt in both countries. Nine years of obligatory schooling were introduced. Even though the character of the Norwegian and the German welfare states differs in many respects, the provision of free, high-quality education at least for a significant proportion of the population was in both cases associated with economic growth along a high-road path, based on specialized, well-educated workers able to cope with technological progress.

It could also be argued that the choice of the federal state NRW is a good one because NRW mirrors the denominationally mixed character of the German nation, having long been one of the most denominationally mixed areas within Germany.Footnote 17 NRW is the most populated of all federal states; during the postwar decades, around a third of West German students went to school there. In education politics, NRW belongs to the more reform-oriented federal states, as opposed to the more conservative and Catholic southern federal states, though it has not been as reform-oriented as some of the Northern federal states or the city state of Berlin.Footnote 18 Norway, on the other hand, was the first country to introduce primary comprehensive education and has stayed true to this course to a higher degree than for example its neighboring country Sweden, where reforms have led to changes (Reference WiborgWiborg, 2012, Reference Wiborg2015).

These are relevant considerations backing up the case selection of this book. However, it would be dishonest to claim that the cases were chosen because of these considerations. Rather, they were chosen because I had a desire to understand these cases better and felt that they contrasted fruitfully. In my discipline, historical sociology, this is considered a good reason. What is most important for historical sociologists, however, is to make sure that they know their cases well. The case-oriented research strategy implies that theory is not “tested” in the variable-oriented sense but that one aims at a dialogue between theory and evidence over time, as one delves into one’s cases and compares them (Reference RaginRagin, 1987). During this process, empirical findings enter into a dialectical relationship with theoretical, analytic frames, inspiring new perspectives on data and theory alike (Reference MjøsetMjøset, 2000; Reference OlsenOlsen, 1994, 76; Reference RaginRagin, 1987; Reference Ragin and AmorosoRagin/Amoroso, 2011, 57ff).

In the case of this book, this dialogue meant that I corrected my original power resources theory–fueled assumption that the outcomes of comprehensive school reforms were mostly a result of conflicts between the left and the right. As I studied the historical material and got to know my cases better, I realized that my understanding had been too heavily influenced by German research on educational inequality. Based on my “rediscovery” of Rokkanian cleavage theory, which clearly resonated with the empirical data, I developed the argument set forth in the remainder of this book: that the different outcomes can only be truly understood in light of the cleavage structure as a whole because crosscutting cleavages decisively shaped actors’ preferences for coalition-making.