Americans are regularly presented with examples of the horrific consequences of US childcare, when children are harmed, sometimes fatally, in unsafe settings. These episodes draw attention to instances of malpractice, neglect, and even violence in US childcare centers. What tends not to rise to the level of public attention is the quotidian reality of early childhood education and care in the United States: that the quality of too many programs is at best mediocre (Reference Barnett, Frede, Blossfeld, Kulic, Skopek and TriventiBarnett and Frede 2017, 153–4). This is the case despite the high cost of these services to parents, creating challenges for many to afford decent care but especially burdening low- and moderate-income families. The consequences of this expensive, variable-quality system reverberate across US society, depressing women’s workforce participation, undermining the potential gains for children of early education, and reproducing class, racial, and gender inequalities.

The root cause of this situation is US reliance on private markets and limited demand-side subsidies to provide early childhood education and care (ECEC) services.Footnote 1 Public aid for childcare and preschool consists of means-tested assistance or programs that reach only a fraction of the population and tax subsidies that fail to cover much of the cost of these services. Parents therefore rely on a market that exists largely because of the low pay received by those employed in this sector, which in turn depends on the low educational requirements for those working in these jobs. One of the many consequences is high staff turnover in ECEC centers, preventing the development of skills and knowledge about the care and education of children. The system is mutually reinforcing, as raising standards for staff education and training would raise pay and lower turnover but render these services prohibitively expensive for most parents, given the lack of public subsidies. The result is a landscape of expensive and flawed ECEC services that fail parents, children, ECEC workers, employers, and society as a whole.

How did we arrive at this point? And what might we do to improve the situation? This paper explores how public options in ECEC can remake our current market-based system into one that lays the foundations for a most just and equitable society. As defined by Sitaraman and Alstott (2019, 27), a public option “guarantees access to important services at a controlled price” but “coexists … with private provision of the same service.” One important rationale for government involvement in social provision, they argue, is to foster equality of opportunity, creating the conditions for people to help themselves succeed in our market economy. Early childhood education and care is fundamental to this goal, but only if programs are safe, enriching, affordable, and widely available. What is needed is an ECEC system that can promote both quality and equality. A public option is the best way to achieve this.

7.1 A Brief History of Markets in US ECEC Provision

The first time the federal government became involved in early childhood education and care was during the Great Depression, when the government instituted federal subsidies for nursery school programs as a way to keep school staff employed. In the 1940s, these and other centers received Lanham Act funding to support women working in war-time industries. The centers were closed at the end of the war, however, so that women would leave the labor force and make room for returning veterans (Reference MichelMichel 1999, chap. 4). Even so, as in other areas of the welfare state (Reference HowardHoward 1997; Reference HackerHacker 2002), congressional decision-makers in the 1950s carved out some tax breaks so that working parents could deduct childcare costs as a business expense. The assumption guiding policymakers at the time, however, was that men would be the main breadwinners and women would be at home caring for children, even though many families did not conform to this vision (Reference CoontzCoontz 1993).

By the late 1960s, however, there was a growing social and political movement to expand access to early education and care. Civil rights activists and child development specialists joined forces to create Head Start – a program that offers education and health services for disadvantaged, preschool-aged children. Despite bipartisan support for 1971 legislation that would have built on the Head Start model and created a national childcare system, President Nixon issued a vitriolic veto of the bill that was a stinging rebuke of Congress. Unbeknownst at the time, the veto not only dashed immediate hopes for a federally subsidized system, but also signaled a turning point in the history of US ECEC provision. Head Start survived the attack, and the federal government expanded tax deductions for childcare costs in an effort to further promote a market of childcare programs. Otherwise, not only was significant, direct support to ECEC off the table, but social conservatives also mobilized opposition in the 1970s and 1980s against policies that encouraged mothers’ employment (Reference MorganMorgan 2001, 239–40). Moreover, intensified conflict over welfare reform contributed to the racialization of public assistance and anything associated with it, including federal spending on childcare (Reference GilensGilens 1999).

Efforts to expand federal ECEC spending since that time have produced moderate increases in means-tested assistance, usually in the form of services aimed at bolstering workforce participation of low-income parents. Aside from Head Start, the Child Care Development Block Grant (CCDBG) is the main source of federal ECEC spending (Table 7.1), mainly through the Child Care Development Fund (CCDF), followed by specialized grants that provide food, home visits, support to children with disabilities, and so forth. The number served by these programs is limited: in 2016, for instance, only 15 percent of the 13.3 million children eligible for childcare subsidies actually benefitted from them (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2019). The number of children served by the CCDF has declined over the past decade, dropping from 1.69 million (served monthly) in 2010 to 1.32 million in 2017 (Child Care Aware of America 2019, 30). One reason for the decline is likely that growing numbers of providers refuse to accept federal subsidies because they have failed to keep up with the real cost of care (Child Care Aware of America 2019, 32–33). Head Start also reaches only a portion of eligible children – by some estimates, just half of those eligible who are African American, 38 percent of Hispanic or Latino children, and 36 percent of Asian children (National Research Council 2018, 125).

Table 7.1 Spending on Major Federal Childcare Programs (2018)

| FY2018 (millions) | Eligibility | |

|---|---|---|

| Head Start | $9,863 | Family income below 100 percent of the federal poverty line. |

| Childcare and Development Block Grant | $8,130 | Family income below 85 percent of state median income, states usually set lower. Parents must be at work, in training, or in school. |

| MIECHV | $400 | States must prioritize certain families, such as those with low incomes. |

| Preschool Development Grant | $250 | Family income below 200 percent of the federal poverty line. |

| IDEA (preschool and part C) | $851 | For children with disabilities and/or developmental delays. |

| CCAMPIS | $50 | Children of low-income postsecondary students, usually with a Pell Grant. |

| FACE | $16 | Indian parents and children in Bureau of Indian Education-funded school. |

| CACFP | $3,638 | Generally low-income children, also elderly or disabled adults. |

| CDCTC | $4,690 | Taxpayers with dependent care expenses. |

| Dependent Care Exclusion | $900 | Taxpayers with expenses eligible for employer-sponsored-dependent care assistance. |

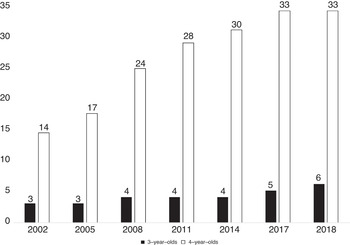

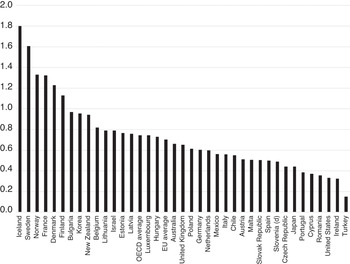

There has been significant expansion in state-level prekindergarten programs since the start of the 2000s, and there are now 61 programs in 44 states and the District of Columbia that enroll almost 1.6 million children (National Institute for Early Education Research 2019, 11). However, enrollment has stagnated since the Great Recession, and thus nationally these programs serve only about one-third of four-year-old and 6 percent of three-year-old children (Figure 7.1), and there are tremendous differences between states in access and the quality of these programs (National Institute for Early Education Research 2019, 10). The truncation of direct public support for ECEC is notable in comparative perspective: as Figure 7.2 shows, the United States is nearly at the bottom of OECD countries in public spending on childcare and preschool education.

Figure 7.1 Percentage of children in state publicly funded pre-K programs

Figure 7.2 Public spending on childcare and early education as a percent of GDP, 2015 or latest available

With most lacking access to public services, families have relied on private markets that are partially subsidized by tax breaks. The Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC) allows parents to deduct a portion of their care expenses on a sliding scale according to income, but this credit is nonrefundable and thus of little use to parents with low incomes.Footnote 2 Twenty-three states also have child and dependent care tax credits, and twelve of these are partially or fully refundable (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine 2018, 74). About 56 percent of firms offer their employees flexible spending programs that allow an individual to shield up to $5,000 of dependent care costs from taxes, while around 7 percent provide childcare on-site or nearby for their employees, but at a cost to parents (National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine 2018, 76). These funds, and parental demand, have helped support expansion of a market of childcare providers, so that even though the US lacks the publicly funded programs that are now prevalent in other countries, significant numbers of US children are in ECEC programs. According to a 2016 survey, around 60 percent of children below the age of five (and not yet in kindergarten) were in some kind of nonparental care, with 59 percent in a center-based program, and 22 percent cared for by a nonrelative in a private home (Reference Corcoran and SteinleyCorcoran and Steinley 2019, 5).Footnote 3

What does the ECEC market look like? In addition to public pre-K, most programs are provided by nongovernmental entities that operate on either a for-profit or nonprofit basis. The former range from mom-and-pop operations, often in private homes, to large chains, such as Kinder Care or Bright Horizons. Nonprofit centers are also highly varied, and include those programs run by religious denominations, universities, elementary schools, and community-based organizations. All told, there are some 54,000 commercial facilities and 21,000 centers run by nonprofits, with a combined annual revenue of roughly $41 billion (Child Care Services 2019). Another form of private care is more individualized: nannies, au pairs, and babysitters that care for children, sometimes through joint arrangements with multiple families. For school-aged children requiring afterschool or summertime care, there also are wide array of programs, of varying auspices.

In sum, lacking public alternatives, most parents have turned to a large and varied marketplace to find care and educational programs for their preschool-aged children. What could be wrong with such a system? The short answer: almost everything.

7.2 The Impact of Market-Based ECEC on Quality and Equality

To get a handle on the many limitations of the US ECEC system, it is necessary to review why policymakers and scholars around the world increasingly favor government involvement in ensuring widespread access to good quality ECEC programs. One rationale concerns child development: the first five years of a child’s life are critical from the standpoint of neurological development, and thus environmental conditions and experiences during that period lay the foundations for lifelong capabilities. As one influential scientific panel concluded, “Virtually every aspect of early human development, from the brain’s evolving circuitry to the child’s capacity for empathy, is affected by the environments and experiences that are encountered in a cumulative fashion, beginning early in the prenatal period and extending throughout the early childhood years” (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council 2000, 6). Services available during early childhood can shape cognitive as well as social development, with potentially lasting effects on the capacities for lifelong learning (OECD 2017, 31). For instance, good quality ECEC programs have been shown to have positive effects on math skills, language, literacy, and social behavior in the short term, with more mixed but suggestive evidence of long-term consequences for school completion, employment, criminality, and health (Reference Yoshikawa, Weiland and Brooks-GunnYoshikawa, Weiland, and Brooks-Gunn 2016; Reference Heckman and KarapakulaHeckman and Karapakula 2019).

A prerequisite for these positive effects, however, is quality. The greatest developmental gains for children come from high-quality services, whereas poor quality programs can negate these benefits (Reference Gambaro, Stewart, Waldfogel, Gambaro, Stewart and WaldfogelGambaro, Stewart, and Waldfogel 2014, 3–6; Reference MelhuishMelhuish 2015, 10). What is a quality program? Child development experts generally capture quality by structural and process measures (Ishimine and Tayler Reference Ishimine and Tayler2014, 273; Reference SlotSlot 2018) – the former includes child-staff ratios, maximum group size requirements, health and safety regulations, and requirements concerning staff qualifications and continuing professional development, while the latter captures the interactions between staff and children. There is some relationship between structural and process quality (Eurofound 2015, 18–26). Growing recognition about the importance of ECEC quality has led to significant investments in these programs across advanced industrialized states, and initiatives by the European Commission, OECD, and other international organizations, to draw attention to this issue (Reference SchleicherSchleicher 2019; Reference Morgan, Garritzman, Hauersermann and PalierMorgan forthcoming).

Quality programs can, in turn, promote equality through a variety of pathways. One set of impacts is on gender equality, as women’s employment choices are shaped in part by availability of good quality and affordable ECEC services. Research on the United States and other countries shows that cost, availability, and quality can all factor into parents’ decisions when it comes to paid work, with effects in particular on mothers’ labor market participation (Reference Hegewisch and GornickHegewisch and Gornick 2011, 128–129). The ramifications of leaving the workplace can be enduring: during lengthy periods of time out of the labor market, human capital degrades, making it more difficult to reenter the workforce later on. The result is a penalty on mothers’ earnings that is more pronounced in countries lacking childcare and other supports to mothers’ employment (Reference Budig, Misra and BoeckmannBudig, Misra, and Boeckmann 2012).

As mothers’ employment affects the financial well-being of households, ECEC access also has broader economic consequences. The era during which one earner could support a family on one income is well past in most advanced industrialized states, as good paying blue-collar jobs have disappeared, unionization rates have fallen, and job insecurity has increased, including for many white-collar workers. In the United States, wage growth has largely stagnated since 2000 for all except those in at least the 90th percentile of the income distribution (Economic Policy Institute 2019). Today, 15 percent of households with children under age eighteen are headed by a single parent, and these households are at particular risk for poverty (Census Bureau 2019). Of the 17.5 percent of children living in poverty, 58.2 percent of them are in households headed by single mothers (Children’s Defense Fund 2017). The reality today is that most households depend on the market incomes of the adults living within them, whether it is a two-parent or single-parent family. Supporting paid work is thus essential to the financial well-being of families. Not only does access to affordable, good quality ECEC programs support mothers’ employment, but these services also can potentially be a source of employment, often for women, as teachers and caregivers.

Finally, promoting broad-based access to quality ECEC programs affects equality of opportunity through its effects on child development. The income-based gap between children in their cognitive capabilities is already apparent when children begin school and tends not to widen very much thereafter. This suggests that the critical period for intervention is before the compulsory school age (Reference Yoshikawa, Weiland and Brooks-GunnYoshikawa, Weiland, and Brooks-Gunn 2016, 22). As Reference ValentinoValentino (2018, 79) sums up the available research on the topic, “achievement gaps between Black and Hispanic children and their White peers and between children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and their higher socioeconomic counterparts are about two-thirds of a standard deviation at the start of kindergarten … the equivalent of about three years of learning in later grades.”

Promoting equality of opportunity through ECEC programs has positive consequences not only for societal well-being but also for the economy as a whole. The potential effects are both short-term and long-term. In the immediate term, assuring parents access to affordable, good-quality care reduces staff turnover and absenteeism. One economic analysis of parents lacking adequate care for children under age three found that the average cost to parents in lost earnings was $3,350, adding up to $37 billion annually, while the yearly cost to businesses was $13 billion (reflecting less revenue and the cost of recruiting new employees). With families paying less in income and sales taxes, the annual cost to taxpayers is $7 billion (Reference BelfieldBelfield 2018). The longer-term economic effects are a source of greater debate, owing to the difficulties of calculating the lasting consequences of investments in ECEC for the productivity to workers or reduced crime rates. That said, conservative estimates hold that for every dollar invested in preschool education there is a return of around three to four dollars (Reference KarolyKaroly 2016).

Recognition of the manifold and multiple benefits of ECEC have spurred expansions of these programs across OECD countries. Even in countries that traditionally shied away from supporting mothers’ employment, recognition of the economic and social realities fueling women’s labor force participation, coupled with growing awareness of the importance of early education for children, has led governments of varying ideological stripes to expand access to ECEC programs. Not all of these initiatives have put as much emphasis on the quality of these programs as they should, and some countries have developed systems rooted in market forces and demand-side subsidies (Reference Morgan, Morel, Palier and PalmeMorgan 2012). Overall, however, there is growing recognition that ECEC is a fundamental feature of what has been called a “social investment” approach to social policy that invests in human capital and prioritizes access and quality in public services in order to promote equality (Morel, Palier, and Palme Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2012).

The market-based ECEC system in the US does not uniformly promote quality and equality. With limited public subsidies, access to programs is highly stratified by income, a reflection of the fact that parents themselves pay much of the cost. One estimate holds that parents pay about 46 percent of ECEC costs, while public funds cover 52 percent and private funds the rest (National Research Council 2018, 56–57), but this is total spending and does not reflect the realities facing individual families who, often with minimal subsidies, struggle to pay for expensive care. In 2018, the average annual cost of childcare in the Northeast reached $26,102 (compared to $13,214 for college tuition), while in the South the average cost was $18,442 (while annual college tuition cost $9,706) (Child Care Aware of America 2019, 12). This represents a hefty, if not impossible, portion of annual income. An OECD analysis found that, after taking into account tax breaks and other subsidies, middle-income and low-income two-earner and single-parent families in the United States paid 30 percent of their earnings on childcare, compared to the OECD average of 17 percent for two-earner families and 11 percent for low-income single-parent households.Footnote 4

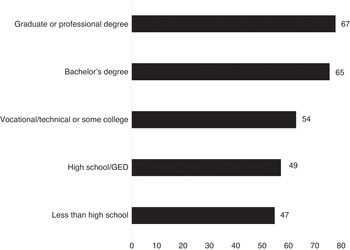

Although parental choices with regard to ECEC reflect a variety of economic and cultural factors, much research concludes that cost is a major determinant of utilization (National Research Council 2018, 120–122). Use of ECEC services rises with socioeconomic status, measured by income and education (see Figure 7.3), and studies have shown that increasing subsidies reduces these gaps in programs use. Access to quality care also is highly dependent on income and also stratifies the population based on race or ethnicity: in the United States, poor and/or minority children are less likely to have access to good quality ECEC programs, compared to white and/or non-poor children (Reference Karoly, Ghosh-Dastidar, Zellman, Perlman and FernyhoughKaroly et al. 2008, 147–150; Reference ValentinoValentino 2018). But quality is a problem that plagues the entire market-based US system. As Barnett and Frede (Reference Barnett and Frede2010, 22) sum up the situation, “few of the preschool programs children attend are of high quality. Most might be rated as mediocre. A significance percentage provides little support for learning and development.”

Figure 7.3 Participation of children below age five (and not yet in kindergarten) in center-based care, by Parental Education Level (2016)

One might wonder how it is that a service parents pay so much for remains inferior in quality. The answer lies in the economics of ECEC programs, in which labor costs amount to 70 percent of operating costs (Child Care Services 2019). As most centers depend heavily on parental fees for revenue, the price parents pay is directly tied to the wages of ECEC staff (Reference WhitebookWhitebook 1999). To maintain profitability, centers must find ways to keep these costs down or else parents will seek out cheaper forms of care, like babysitters or relatives. Large chains reap some economies of scale, but the ECEC market overall is characterized by considerable fragmentation and the predominance of small operations. Given the low subsidies and state-level regulations on the number of staff required per child, the way ECEC services survive is to squeeze the wages and benefits of their employees, which in turn assumes that the employees are not highly educated or trained or else they would find other forms of employment (Child Care Services 2019).

As a result, the US ECEC market’s existence hinges on very low-paid staff that are ill-trained, too often not supported in their work, and unlikely to stay in the position for very long. ECEC workers are “some of the most erratically trained and poorly paid professionals in the United States” (Reference Phillips, Austin and WhitebookPhillips, Austin, and Whitebook 2016, 140). In 2018, the mean hourly wage for childcare workers was $11.83, resulting in a mean annual wage of $24,610, while preschool teachers earned an average wage of $16.54 (and average annual earnings of $34,410).Footnote 5 For childcare workers, their earnings are less than half the mean hourly wage in the United States ($24.98), while those in the preschool sector earned 66 percent of the mean hourly wage. This represents incomes at or below the poverty threshold, which was $25,100 for a family of four in 2018.Footnote 6 Many who work in this sector also lack employer-provided benefits, such as health insurance (National Research Council 2018, 37), and more than half of childcare workers’ households (53 percent) and 43 percent of preschool and kindergarten teachers’ households, are enrolled in at least one public support program (compared to 21 percent for all workers) (Early Childhood Workforce Index 2018, chap. 3, 14).Footnote 7

The qualifications required of ECEC workers vary markedly by state, type of center, and job position, but generally are not very high. State-funded prekindergarten programs often require either a bachelor’s degree (59 percent currently have such a requirement) and/or specialized prekindergarten training (81.9 percent require this) (NIEE 2019, 11), while the Head Start program requires that at least half of teachers have a bachelor’s or advanced degree in early childhood education. In 2013, about 66 percent of staff working with preschool-aged children had a BA degree (National Research Council 2015, 424). While this still falls below the recommendations of the Institute of Medicine and National Research Council that all preschool teachers have a BA and training in early childhood education (NIEE 2019, 14), it is nonetheless better than the situation in other childcare centers. Only one state has a similar educational/training requirement for other center-based programs, while seventeen states require less than a high school degree or GED (National Research Council 2015, 424). Teachers in these centers are not required to have any prior experience in early childhood in forty-one states (National Research Council 2015, 425).

Low wages and a frequent lack of benefits lead to high rates of employee turnover in ECEC programs. Whether one comes to this line of work with specialized training or not, experience and continuing professional development programs (if they exist) can help develop skills and coping mechanisms for working in what can be a stressful environment. Yet, turnover remains high in this sector, at around 30–40 percent per year, with staff often complaining of low pay, workplace stress, and the lack of benefits (National Research Council 2015, 471; Child Care Services 2019). Turnover rates are highest in for-profit centers, whether they be chains, franchises, or independent operations, when compared to other nonprofit and publicly sponsored centers, and it is also in those for-profit centers that both the pay and qualification levels of the staff are the lowest (Reference Whitebook, Phillips and HowesWhitebook, Phillips, and Howes 2014, 26–30).

All of these features of the ECEC system reinforce inequalities in US society. Not only is class inequality reinforced by disparities in the access of poor children to high quality developmental services, but these disparities reinforce achievement gaps between minority groups. To reiterate the point made earlier: some of the children who would especially benefit from access to good quality ECEC programs are less likely to access them, and in the United States that has particular implications for low-income minority children. The precise role of access disparities in shaping these differences remains a subject of continuing research, yet, we know that some of the groups of children that would most benefit from enriching, developmental care, or early education are less likely to access it (Reference Karoly, Ghosh-Dastidar, Zellman, Perlman and FernyhoughKaroly et al. 2008, 147–150; Reference LaddLadd 2017). The expansion of public pre-K and other targeted programs has improved access to children from lower- and middle-income families, but disparities in access based on income are still significant, as is true for children from Latino families (Chaudry and Datta Reference Chaudry and Rupa Datta2017, 9, 11).Footnote 8

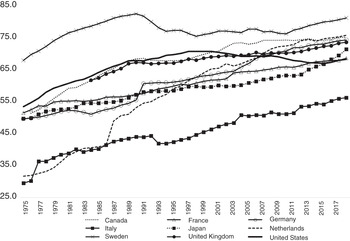

The US ECEC system also contributes to gender inequality. After rising rapidly during the 1970s and 1980s, women’s employment rates have stagnated in the US since the 1990s, in contrast to trends in many other advanced industrialized states (Figure 7.4). The high cost of childcare is one factor that has depressed US mothers’ employment (Reference KubotaKubota 2018). And the treatment of the ECEC workforce also contributes to, rather than potentially mitigating, both gender and economic disparities. Employees in ECEC programs are overwhelmingly female and have relatively low education and skills. They also are disproportionately racial and ethnic minorities: around 40 percent of the ECEC workforce, in centers and registered home-based care, consists of people of color, which is true of half of unlicensed home-based care providers (Early Childhood Workforce Index). It is on the backs of these low-paid and often underappreciated workers that our market-based ECEC system operates.

Figure 7.4 Labor force participation rates of women, ages 15–64, 1975–2018

7.3 What a Public Option Could Look Like

A public option can rectify many of these problems and could take various forms. One type of public option could be modeled after our public schools, with universal access to publicly run programs alongside private programs that continue to operate for those parents who prefer them. This approach, outlined by Sitaraman and Alstott (Reference Sitaraman and Alstott2019, chap. 10), would involve a first layer of services for children below the age of three, followed by universal pre-K programs that could be integrated with local public schools. Access would be guaranteed, being either free of charge, as is the case with public schools, or available to parents according to sliding-scale fees based on income. Another approach would build on our existing system of ECEC providers but use quality-enhancing regulations as well as supply-side subsidies to ensure services that are affordable and of good quality. Private, nonsubsidized services could also continue to offer their own programs, but many would likely agree to higher program standards and requirements in return for public subsidies.

One can also envision a mix of these two approaches: directly provided programs as well as subsidized private providers who are required to meet the same kinds of standards as the publicly provided programs in terms of facilities requirements, curriculum, staff qualifications and pay, and training. One example of a mixed model is the Department of Defense (DoD) childcare system for military personnel, which employs 23,000 childcare workers and provides for around 200,000 children (Reference KamarckKamarck 2018). The backbone of the military system is government-provided centers that must meet high standards for the quality of their facilities and staff training and pay. To supplement the DoD-provided centers, there also is a fee assistance program in which DoD makes direct payments to civilian ECEC providers.Footnote 9 The latter are required to meet many of the same high standards as the military’s centers, including the requirement that they be accredited by a nationally recognized accreditation body.Footnote 10 For both DoD-provided ECEC and that offered by subsidized, civilian providers, parental fees are set according to income and the overall cost to parents is significantly below that paid for nonsubsidized care in private markets (Reference KamarckKamarck 2018, 12).

Whether through direct government provision or through subsidies to existing providers, the key is to intervene on the supply-side to make sure that ECEC programs are broadly available and of good quality. In theory, we might imagine a system in which generous and refundable demand-side subsidies – refundable tax credits or vouchers – ensure that lower- and moderate-income people have most of the cost of their services covered. Combining this with strict regulations on quality should ideally then enable a subsidized market of private, for-profit providers that will compete for parents’ dollars. In practice, there are grounds for skepticism that such a system would be sustainable, for many of the reasons that Sitaraman and Alstott (Reference Sitaraman and Alstott2019, 187–191) outline. Providers may just raise prices to gobble up parents’ vouchers, and the variable price of care across the country would make it difficult to tailor the voucher to the right cost. Volatility in individual incomes, particularly pronounced among lower income people, adds further complexity to figuring out how to create a voucher or refundable tax credit that equitably supports parents with ECEC costs. To these technical challenges, I would add a political one that is particularly pertinent in the United States, where organized interests often mobilize to influence policy in their favor. Private providers exist to maximize profits and, as was noted earlier, the economics of ECEC is relentless on this score. Staff costs are everything and there are few productivity gains to be had (unless we are willing to turn our children over to robots). Facing strict requirements on staff pay, educational requirements, and strictures on class sizes and staff–child ratios, for-profit firms in the US context will lobby hard to reduce these requirements.

By intervening on the supply side through either direct provision or subsidies to providers, policymakers could then also increase requirements for the education, training, and continuing professional development of those working in these centers. Decoupling pay from parental fees is critical to enabling a transformation of these jobs into decently paid, opportunity-enhancing forms of employment. Staff not only could earn a livable wage but have opportunities for training and other programs that provide a career ladder. Some states have already sought to develop such ladders through ECEC programs, so that low-skilled staff can gain support for continuing education that enables them to advance into more skilled and better remunerated positions in the ECEC workforce. Such initiatives could also be thought of as a public option for ECEC education and training: publicly provided or publicly subsidized programs for those seeking employment in the ECEC field.

However, as long as these positions in ECEC programs offer low pay and often inadequate or nonexistent benefits, many will jump off these ladders and seek out other forms of employment. Severing the connection between parental fees and the pay received by ECEC staff has been crucial to the success of the military ECEC program in delivering quality care at a reasonable cost. In the words of one Army official in charge of the system, “We broke the link between parent fees and personnel costs. You have the fair share fees on the one side, and you have the appropriate wage [for providers] on the other, and the armed services make up the difference” (cited in Reference CovertCovert 2017). That is the essence of a public option in ECEC.

7.4 Conclusion: Joining the Rest of the Advanced Industrialized World

The United States was not alone in using social policy to support single-earner families in the post-WWII decades. To the contrary, governments in many advanced industrialized countries, including Australia, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Switzerland, shied away from investments in public ECEC programs out of a belief that such responsibilities were better left to families and local voluntary organizations. In the past three decades, however, policymakers in these countries came to realize that the world had changed around them. Women were working, there were more single-parent families, and traditional neighborhood structures were no longer available to provide supportive environments for young children. Demographic aging highlighted the importance of helping parents combine work and family, so that women’s workplace aspirations would not clash with their desire to have children, leading to zero-sum trade-offs that depress fertility rates. And research showed the critical importance of investments during the early years of children’s lives for maximizing their lifelong potential. Leftists and neoclassical economists alike all came to realize that one of the most important things government can do is ensure there are safe and stimulating learning environments for all young children.

It is well past time for the United States to join much of the advanced industrialized world in developing a public ECEC option. Such programs can provide developmentally stimulating programs to young children that also enable parents to be in paid employment. Access to these services is especially important for children experiencing various forms of disadvantage owing to low family income, migrant status, and/or disability. ECEC also can provide employment, often for less-skilled and/or lower-income women. In short, ECEC programs can help fight poverty, promote equal opportunity, and foster societal well-being, and in so doing they embody the many goals of the public option.