Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Dedication

- Introduction

- 1 ‘Living modernly's living quickly’: Towards Travelling Light

- 2 ‘A purse of her own’: Women and Carriage

- 3 ‘No one is safe from the beggar's pack’: Portability and Precarity

- 4 ‘Have you anything to declare?’: Portable Selves on Trial

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

3 - ‘No one is safe from the beggar's pack’: Portability and Precarity

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 December 2017

- Frontmatter

- Contents

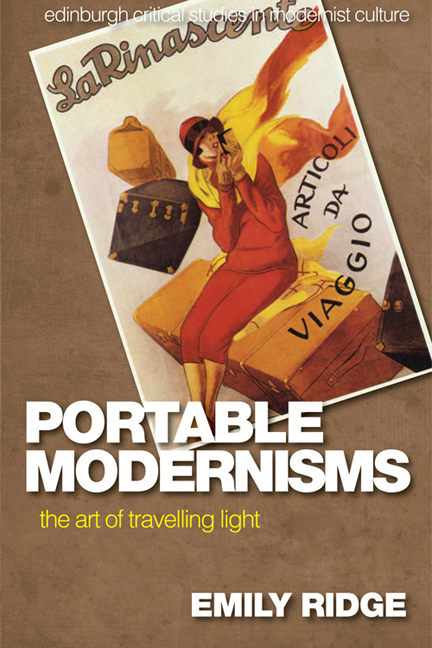

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Dedication

- Introduction

- 1 ‘Living modernly's living quickly’: Towards Travelling Light

- 2 ‘A purse of her own’: Women and Carriage

- 3 ‘No one is safe from the beggar's pack’: Portability and Precarity

- 4 ‘Have you anything to declare?’: Portable Selves on Trial

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

After an almost exclusive concentration on women and portability in Chapter 2, the scope of Chapter 3 will be more expansive and will loosely focus on the period between the two world wars. I have demonstrated the import of women's luggage as a subversive symbol for the New Woman and as a site of early modernist innovation. I have equally dwelt on figurations of the woman's bag as revelatory of the impedimental difficulties and pressures attending any endeavour to achieve an uncompromised form of freedom. The following more inclusive discussion of portable forms and experiences, both men's and women's, addresses the intensification of these issues during the interwar period. It is not my intention to imply that the turn-of-the-century preoccupation with women's bags directly incited a more general sense of the bag's symbolic potential, though this might well be true in some cases. It would be more accurate to say, rather, that the figure of the woman who carried her own bag embodied an exclusionary form of dispossession as well as a departure from or challenge to a proprietorial status quo, which came to be of driving importance for a range of modernist writers, whatever their sex. In other words, the emancipatory, disruptive, progressive, conflictual and ambiguous connotations of the woman's bag, as I have described, came to resonate more widely, making luggage-related forms and metaphors more widely applicable. The specific question of the freedom of the woman becomes a question of the freedom of the individual in the face of rising forms of authoritarian oppression in Europe between the wars, forms of totalitarian and bureaucratic power that subjected each and every person to external systems of control and rendered the condition of dispossession a more prevailing prospect. Luggage carries over as a vital metaphor through which to explore contradictory desires for freedom and security more broadly in literature of the 1920s and 1930s. It further carries over as a vital metaphor to probe the significance of the miniature, whether as subversive or vulnerable element, as set against gigantic, often unseen and unnameable forces, to re-invoke Susan Stewart's terms.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Portable ModernismsThe Art of Travelling Light, pp. 108 - 143Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2017